by Dale Wayne Slusser

Swannanoa, nymph of beauty,

I would woo thee in my rhyme;

Wildest, brightest, loveliest river,

Of sunny Southern clime!

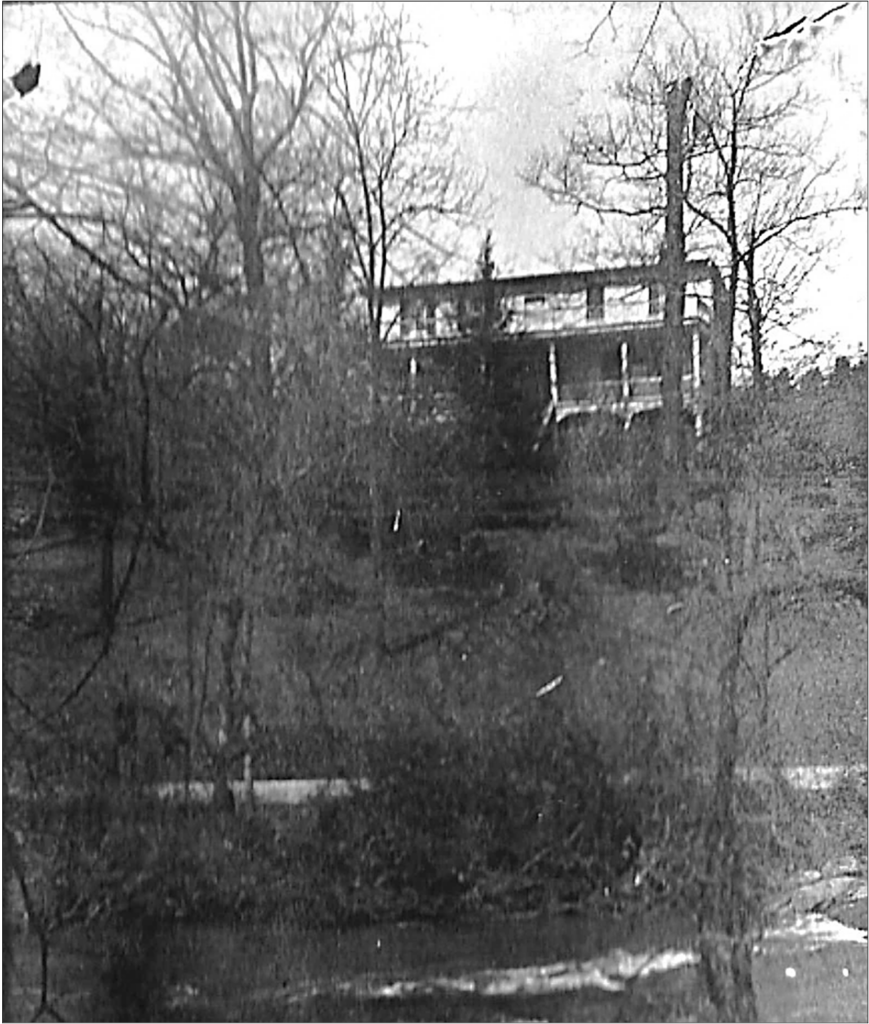

This early 20th-century photo shows Azalea sitting on the hillside along the banks of the Swannanoa River. The Swannanoa River Road runs between Azalea and the river, at the foot of the hill.– Photo courtesy– Louisa Emmons, Morganton, NC.

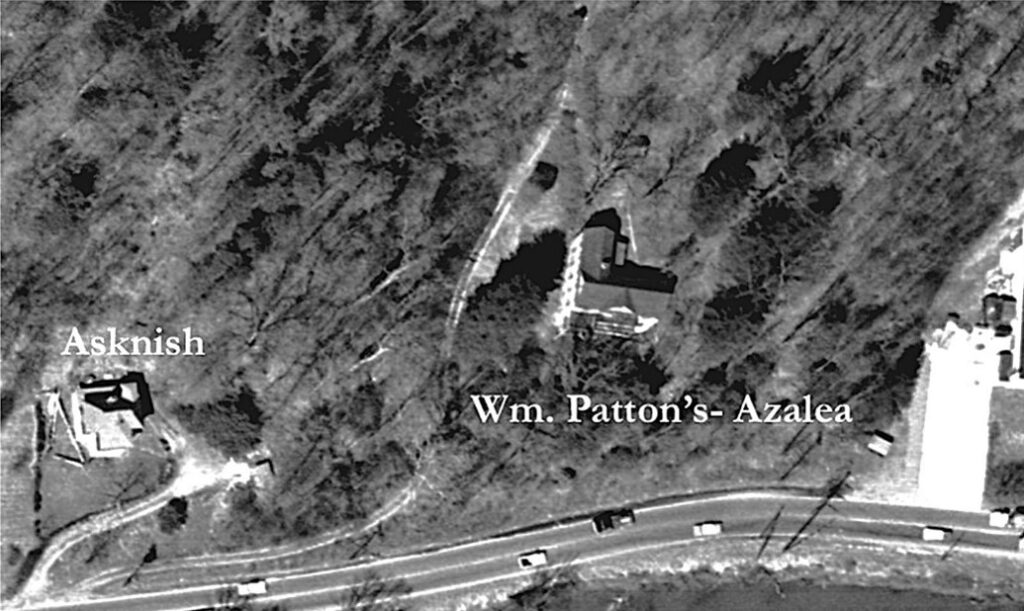

Over a decade ago, while researching the former “Asknish” cottage which sat at 110 Swannanoa River Road, I noticed from its original deed that the cottage was built on “a portion of the original Azalea Property owned by William Patton of Charleston, SC.”[1] In my previous research and writing on the Ravenscroft School, I had often seen references to William Patton’s “Azalea”, but until the day I read that deed (in 2013) I had no idea of its location. It was that deed reference to “Azalea” which provided the impetus for my decade-long search for the forgotten houses along the Swannanoa. My first discovery was that, although William Patton was the first to call the house Azalea, he was not the builder nor the first owner of Azalea, and that it was first known as the “Trescott House”.

“HO! FOR THE MOUNTAINS”, advertised W. P. Blair in an 1871 Charleston, South Carolina newspaper. Blair, who owned the stagecoach line from Asheville, NC to Greenville, SC, posting his advertisement under the column titled “Summer Resorts”, further advertised: “PARTIES visiting Flat Rock, N. C., or Asheville, N. C. will find comfortable Stages leaving Greenville, S. C. every, MONDAY, THURSDAY and SATURDAY MORNINGS, reaching Hendersonville for supper and Asheville for dinner next day.”[2] This relationship between Charleston and Western North Carolina had been established early in the nineteenth century when the Buncombe Turnpike was built, in 1828, from Greeneville, Tennessee through Asheville, to Greenville, South Carolina, where it met with the State road to Charleston. The wealthy Charlestonians began to use this route to escape to the mountains of Western North Carolina during the miasma of the hot mosquito-infested Charleston summers, and during disease epidemic outbreaks. By the 1840’s, due to the influence and promotion of another part-time Charlestonian, J. F. E. Hardy, Charlestonians were regularly and routinely escaping to the mountains for the healthful and healing “effects” of Asheville’s climate.

James Freeman Epps Hardy, a native of Newberry, South Carolina, moved to Asheville in 1821 at the age of nineteen for health reasons. One of his lungs had failed and the other was severely weakened. Hardy soon regained his health, so much so that he decided not only to make Asheville his permanent home, but in 1824 he married Jane Shaw Patton, the daughter of one of Asheville’s most prominent citizens, James Patton. Hardy’s healing was so impactful that shortly after marrying, in 1825, Hardy and his bride moved to Charleston where Hardy began his studies at the College of Medicine. After graduating with his medical degree in 1831, Hardy moved back to Asheville and began a lifetime career as a renown local physician and surgeon.[3]

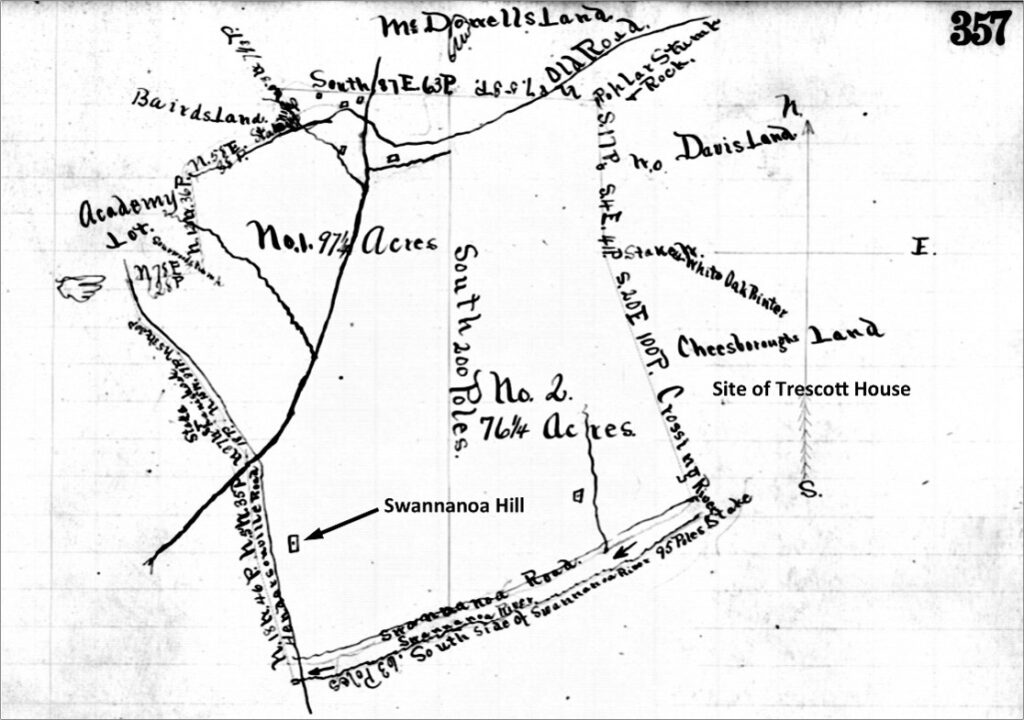

In 1836, Dr. Hardy decided to build a house for his friend and former medical college professor from Charleston, Dr. Samuel H. Dickson. Dickson’s brother, Dr. John Dickson was already a resident of Asheville and mentor of Dr. Hardy. Dr. Hardy built “Swannanoa Hill” for Dr. S. H. Dickson on a forty-acre portion of a 320-acre farm that Hardy had purchased from the heirs of William Forster, Jr. in 1834.[4] Dr. Hardy bought “Swannanoa Hill” and its surrounding property from Dr. Samuel H. Dickson in 1843, to make it his own home. The following year, 1844, Dr. Hardy sold a twenty-acre parcel on the southeast corner of his 320-acre Swannanoa Hill property to “Miss Elizabeth C. Trescott of the City of Charleston”.[5] The key to the story of Azalea/Trescott House is that “The Trescotts”, like William Patton, were “of Charleston”.

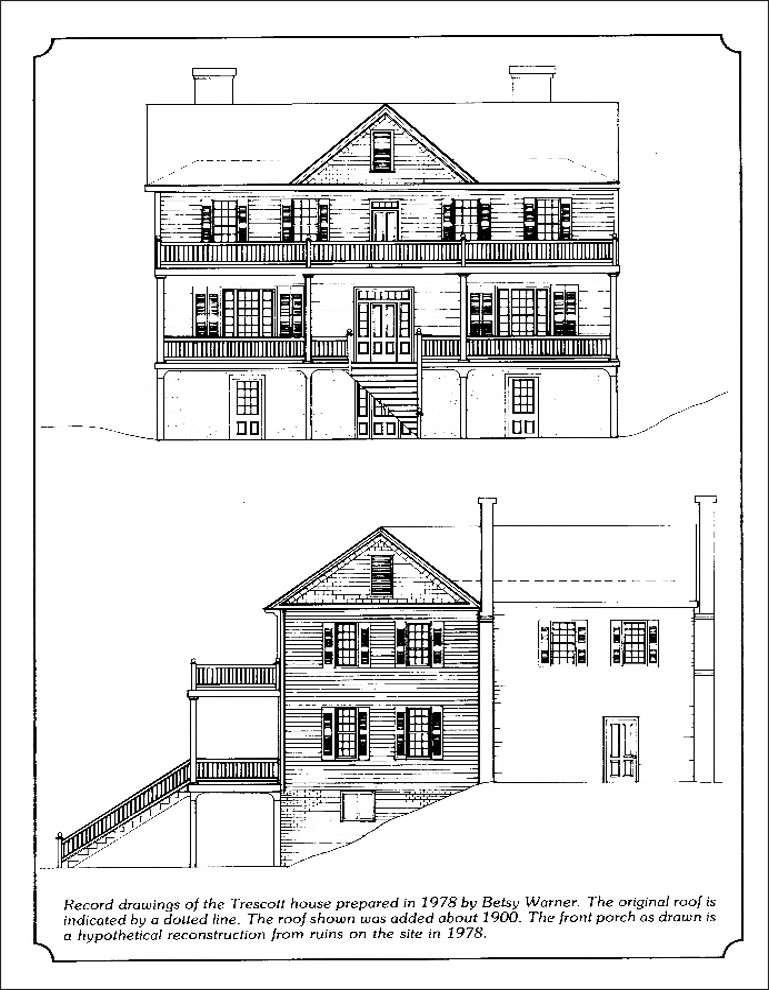

The notes from the county-wide architectural/historic resources survey of the 1970’s records that Azalea “was built in 1848 by the Trescotts of Charleston using slave labor.”[6] The inference and general thought being that the house was built in 1848 by a “Mr. & Mrs.” Trescott using their own enslaved laborers. Although there are grains of truth in that legend, the true facts and story behind the building of the “Trescott House” are more fascinating and are (dare I say a “tidbit” of) a glimpse into pre-1850 house-building in Asheville and Buncombe County.

This 1887 Plat of the Swannanoa Hill property shows the site of the Trescott House (marked as “Cheesborough lands) just east of it. The Trescott site was originally part of the Swannanoa Hill property, sold to the Trescotts by Dr. Hardy in 1844. – Image from Deed book 57, page 348.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Asheville, NC.

In 1847, a correspondent of the Charleston Courier, who was visiting Asheville, reported that the Trescott house, which he described as “Next to Swannanoa Hill, on the same mountain”, “is the residence of Mrs. Caroline M. Trescott of Charleston”.[7] So who was “Mrs. Caroline M. Trescott”, the reported owner of the house? But then who was “Elizabeth C. Trescott”, whose name was on the deed? The short answer is that they were mother and daughter. However, their story is a long, complicated, and sad tale. And although the ladies were from Charleston, and did at one time own enslaved people, the building of their Asheville home is a much different tale from the image we have of a rich plantation owner from Charleston bringing his enslaved people up to Asheville to build his summer home.

“Mrs. Caroline M. Trescott” was born Caroline Markley to Abraham Markley and his wife Mary Gasser Markley, around 1796 in Charleston, South Carolina. In December of 1814, Caroline Markley married William Trescott at St. Phillip’s Episcopal Church.[8] William Trescott, not to be confused with his more famous nephew, William Henry Trescott, was born in 1784 to Edward Trescott and his wife Rachel Catherine Bocquet Trescott. Edward Trescott, considered one of the early pioneers of Charleston, had become a wealthy merchant and planter. Edward Trescott’s plantation, named by him, “Harry Hill”, after a Native-American named King Harry, was north of Charleston near what is now Monck’s Corner, SC. William Trescott not only came from this wealthy family, but by the time of his marriage to Caroline Markley, William was already a prosperous attorney with offices at 213 Meeting Street in downtown Charleston.[9] The newlyweds, William and Caroline had their first child, a son Edward Henry, in October of 1815. Two years later, in 1817 the Trescotts’ baby daughter, Elizabeth C. Trescott was born. However, a few months later, in September 1817, William Trescott died at age 33, leaving a wife and two infant children. A contemporary report claimed that William Trescott had died “from a fever induced by exposure to the night air.”[10] To add to the young family’s sorrow, William Trescott died intestate (with no Will), causing his estate to go into probate. This was the beginning of a long and tortuous financial struggle for Caroline M. Trescott and her two minor children.

This house at 88 Broad Street in Charleston, SC was William Trescott’s house, which his father, Edward Trescott purchased from William’s estate in 1818. -Photo by Brian Scott of Anderson, SC 09/20/2011- Photo ID=175252, Historical Marker Database www.HMdb.org.

In March of 1818, in order to settle William Trescott’s estate, the Court of Chancery decreed that the family’s house be sold at a courthouse sale. William’s father, Edward Trescott, purchased the house at the sale, with a bond “in penalty of $25,000, conditioned for the payment of $12,800, in two, four, and six years, with interest from the date-the whole of the interest to be paid annually”.[11] However, Edward Trescott died in November of 1818, before even paying his first payment. In his will[12], Edward had appointed his son Dr. John S Trescott as his executor, and after granting a few special legacies, Edward had willed that the residue (which was considerable) of his estate should be divided four ways: a fourth going to each of his sons, Dr. John S., Henry, and George, and a fourth going to his son William’s minor children (Edward Henry and Elizabeth C. Trescott) through their mother, Caroline M. Trescott, acting as their guardian. Although the Court of Equity commissioners of Edward’s estate allotted to each heir “a considerable estate in lands, negroes, and bank stocks, amounting to upwards of $30,000 to each respectively”, no provision of payment on the bond was even considered.[13] In the division of Edward’s estate, his son Henry (executor of William’s estate) got the house that Edward had purchased from William’s estate. To make matters worse, Dr. John S. Trescott died intestate in 1820, before having paid the bond owed by Edward’s estate to Caroline M. Trescott.

After the death of his brother Dr. John Trescott, Henry took out “letters of administration de bonis non” complaining that Edward’s estate had not yet been settled, and having himself assigned as the new executor. And then in 1821, Henry complained to Caroline M. Trescott that it was “not equitable” that his portion of the estate came to him “incumbered” (with the lien for the bond), while the other heirs’ portions were “unencumbered”. Henry therefore convinced Caroline “to have her lien released on the house by entering satisfaction on the mortgage, and to receive his bond as administrator of the said Edward Trescott for the balance due her.”[14] Although there was no money left in Edward’s estate to pay off the bond, Caroline M. Trescott agreed to the new bond as she believed that it was agreed the heirs would pay off the bond by each giving a portion of their inheritance (legacy) to pay it off. One of the heirs, Caroline’s sister-in-law, also named Caroline (widow of William’s brother, Dr. John S. Trescott), did not agree to the arrangement, and refused to pay her portion. Caroline M. Trescott ended up taking her claim to court in 1826, in a case called “C. M. Trescott vs C. C. Trescott” where after an appeal, the court ordered that the original bond of Edward Trescott be reinstated and that the balance due be paid to Caroline out of Edward’s estate (either directly or by the other heirs).[15] It appears that the heirs had to pay their portion-but it took several years for them to pay up. For instance, as late as 1829, M. I. Keith, the Master of Equity, through the firm of Ogier, Bee & Carter, advertised for sale, a group of 22 slaves, and the title of advertisement read: “In Chancery-C. M. Trescott vs C. C. Trescott, Adm’x. Dr. J. S. Trescott and others”.[16] No doubt this was to pay Caroline S. Trescott’s portion to pay off the bond to Caroline M. Trescott, as ordered by the court.

This is the block of Coming Street (described as “between Vanderhorst and Boundary Street (now Calhoun St.)” where Caroline and the children had moved to after the death of her husband in 1817.- Google Image, January 2023, Google.com.

In 1824, while Caroline M. Trescott was fighting for her inheritance (though actually the inheritance of her two children Edward Henry and Elizabeth) her father, Abraham Markley passed away and left Caroline, among her allotted portion of the inheritance, a “house in Mazyckborough”, which I believe was the house on Coming Street where she had moved to after Wiliam’s death. So, although Caroline M. Trescott was not left destitute, she was certainly, for her supposed class and social status, be considered a “poor widow”.

In 1841, after the inheritances (or lack thereof) had been settled, and Caroline was approaching fifty-years of age, and her children now being young adults, she decided to invest in a summer home in the mountains. Caroline first purchased, in her son Edward Henry Trescott’s name (on the deed), property in Chunn’s Cove in East Asheville from Samuel Chunn for $1,200.[17] This property appears to have been on the east/south side of Town Mountain near Vance Gap Road. Then in the Fall of 1841, a series of notices began appearing in the Asheville newspapers, from the Buncombe County July Term of the “Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions”, as per the recent case of “Ephraim Clayton & Jas. W. Patton vs C. M. Trescott” that the defendant (C. M. Trescott) was ordered to appear at the next court session in September, and that if she did not appear, judgement would be “entered against her and the lands levied on be condemned to satisfy plaintiff’s demands.”[18] Had Caroline hired builder Ephraim Clayton to build a house on the Chunn’s Cove property, or had she just borrowed the purchase money from these two men, Clayton and Patton? It’s not clear what the debt was for, as I have found no recorded deeds of trust on this property, and when the Trescotts sold the property in 1846, it did not mention any liens against the title. An interesting note to this story is that when Edward H. Trescott sold the property in 1846, he sold it to Stephen Lee. Whereupon Stephen Lee moved his boys’ school from William Patton’s Swannanoa Lodge (present day site of the Cloisters Condominiums), where he had started his school a few years earlier, to its famed Chunns Cove site.[19]

While still owning the Chunns Cove property, in 1844, Caroline M. Trescott decided to buy a second property in Asheville. It was then that she purchased the 20-acre site along the Swannanoa River Road from Dr. J. F. E. Hardy, for only one hundred dollars.[20] This time she put the title to the property in her daughter’s name, “Elizabeth C. Trescott”. At the time, both Edward Henry and Elizabeth were in their mid-twenties, so it’s unclear whether Caroline Trescott was using her children’s money to buy the properties, or whether she was using her own money but buying the properties for her children?

Legend has it that the house was built by enslaved people brought up from the Trescott’s plantation in Charleston. However, as chronicled earlier, Caroline M. Trescott’s husband died without a will, after only three years of marriage, leaving her as a young widow with two infant children. As William Trescott, Caroline’s husband, was an attorney and they had no plantation, they owned very few enslaved people. In fact, the 1820 U. S. Census (just three years after William’s death) recorded that “Mrs. William Trescott” owned six enslaved people, and only three of them were male, and of the three males, two were under the age of 14.[21] And an entry in the 1840 U. S. Census, for “W Trescott or [M Trescott]”, which appears to be for Mrs. Trescott, shows that by 1844, she owned only four enslaved people.[22] I had entertained the thought that builder Ephraim Clayton used enslaved labor, however the 1840 U. S. Census shows that in his household (probably at his farm on the west bank of the French Broad River where he had a lumber and millwork operation) there were 15 people, 10 of who were recorded as “persons employed in manufacture or trade” and only two of them were African-Americans, one a “slave” and the other recorded under “free colored persons”.[23] George W. Shackleford, Clayton’s partner, who was as masonry contractor doesn’t show on the 1840 U. S. Census, and in 1850 he is recorded as enslaving one woman.[24] It is possible that Clayton and Shackleford could have contracted additional enslaved labor from other local families—leasing out enslaved individuals as laborers for specific projects was a common practice in Buncombe County.

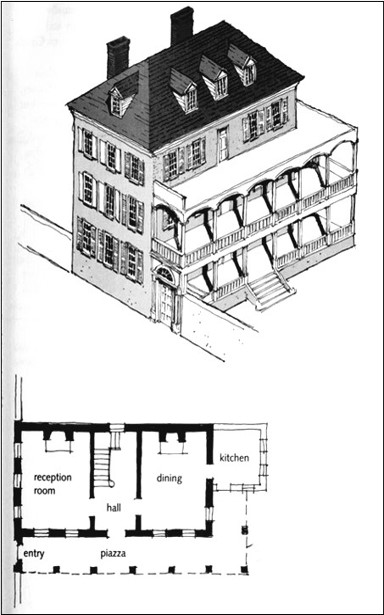

Caroline M. Trescott built a three-story house (2-story wood frame on a raised brick basement) on her new property. I suspect that Mrs. Trescott hired local builders Ephraim Clayton and George W. Shackleford as the contractors for the house. I can find no indication of who may have designed the house; however, it appears to have been designed much like a typical Charleston “single-house”.

Architect and author, Witold Rybcyznski, in his recently published book, Charleston Fancy, gives us a concise description of the Charleston “single-house” type:

“Single houses are narrow two-story buildings-a single room wide, hence the name- with the gable end facing the street, and a side yard overlooked by piazzas, or verandas, on both floors. The arrangement allows cross ventilation, which suits the hot climate, and is adaptable to a variety of sizes, ranging from grand mansions with tall ceilings and deep piazzas to modest homes…”.[25]

These sketches show what a “typical” Charleston Single-House looks like- long and narrow, one-room deep, with multi-story south-facing piazzas. – American Houses: A Field Guide to the Architecture of the Home, by Gerald L. Foster (New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004), p. 155.

The floor plan of a typical Charleston single-house consisted of two rooms per floor, one on each side of a central entrance and stair hall, which was entered from the center of the piazza. Each room had a separate fireplace on the wall opposite the piazza wall, with the fireplace and chimney breast projecting into the interior of the rooms. The piazzas were along the long wall, perpendicular to the street, and usually faced south overlooking a small side yard.

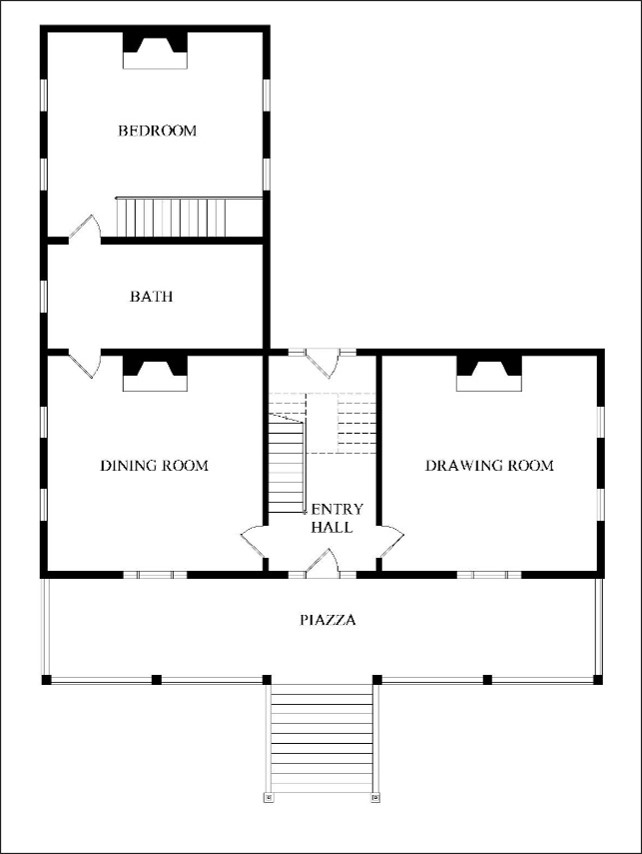

The Trescott House was built as a Charleston single-house transposed from an urban setting and adapted for a rural/country setting. The one-room deep, two-story house with its south facing piazzas had the floor plan of a single-house with its center entrance and stair hall, flanked on each side by one room on each story. A distinctive characteristic of the Trescott House, typical with a Charleston Single-House, are the rear wall interior fireplaces. This is significant as the houses being built at that time in Buncombe County (and most of North Carolina) had their fireplaces and chimneys built on the end walls, projecting out on the exterior.

The only difference from a Charleston single-house was that the Trescott house was turned so that the long front walls with its piazzas faced the street (Swannanoa River Road) allowing the house to be entered directly through the center of the first floor piazza (aligned with the front entrance), rather than having to access the front door via a door at the end of the piazzas (as is the case with the Charleston Single-house).

The floor plan of Azalea shows many of the characteristics of a typical Charleston Single-House. It was long and narrow, one-room deep, with multi-story south-facing piazzas. Also, a distinctive characteristic were the rear wall interior fireplaces. – Sketch by the author, 2024.

Except for the 1847 report (mentioned earlier) which merely acknowledged the presence and location of “the residence of Mrs. Caroline M. Trescott of Charleston”, I can find not much other evidence of the Trescotts occupying the house. Was it just a summer home or did they live there permanently? I suspect it was just their summer home as during those years of ownership Caroline and Elizabeth showed in the directories and census (1850) as living in Charleston. In fact, in the 1850 census “Elizabeth Trescott-aged 60” (who I believe was Caroline Elizabeth) and “Eliza Trescott-age 30” (who I believe was Caroline’s daughter Elizabeth C.) as living in a “Boarding House” operated by “C. D. Eason”.[26]

The building of Azalea seemed to have been a financial stretch for Caroline and Elizabeth, as both in 1850 and 1851, Elizabeth C. Trescott used Azalea as collateral on two separate loans. In June of 1850, Elizabeth C. Trescott used the property as collateral to secure a loan from “Mrs. A. Laborde of the city of Charleston” of $495, with a bond of $1,190.[27] “Mrs. A. Laborde” was the widow of Francis P. Laborde (who had died in 1840[28]). “Mrs. Ann Laborde” was listed in the 1849 Charleston City Directory[29] as having “Boarders” at her house at 74 Beaufain Street in Charleston. Interestingly, the Trescott ladies do not show in the 1849 Charleston Directory, which I suspect was because either they were in Asheville at the time, or perhaps they were “boarding” with Mrs. Laborde and had not participated in the census. Again, in February of 1851, Elizabeth C. Trescott used Azalea as collateral for a loan of $208 (with a bond of $436) from “Mrs. C. D. Eason”[30], who as mentioned earlier was then Elizabeth’s landlord at her boarding house in Charleston.

Mrs. C. D. Eason’s Boarding House at 4 Glebe Street in Charleston, SC, where Caroline and Elizabeth Trescott were living when they built Azalea in Asheville in 1847. – From Wikimedia Commons, File:4 Glebe St.JPG- the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

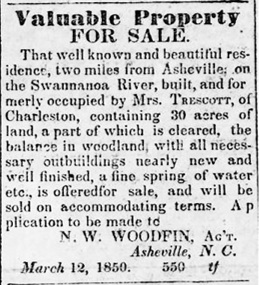

Not surprisingly, less than a month after securing the loan from Mrs. Eason, in March of 1851, the Trescott ladies appointed Asheville attorney Nicholas Woodfin as their agent to sell the Trescott house in Asheville. Nicholas Woodfin advertised:

“Valuable Property For Sale: That well known and beautiful residence two miles from Asheville, on the Swannanoa River, built, and formerly occupied by Mrs. Trescott of Charleston, containing 30 acres of land, a part of which is cleared, the balance in woodland, with all necessary outbuildings nearly new and well finished, a fine spring of water etc., is offered or sale, and will be sold on accommodating terms. Application to be made to N. W. Woodfin, Ag’t. Asheville N. C.”

It took over a year to find a buyer, but in September of 1852, fellow Charlestonian, William Patton, purchased the Trescott House with its twenty-acre property, for $1,000.[31] The Trescott ladies lived the remainder of their lives in relative obscurity and genteel poverty. Caroline M. Trescott appears (the records are scant) to have only lived a few years more, dying on “Elizabeth Street” in Charleston in 1856.[32] Caroline’s son, Edward Henry Trescott became a doctor and moved to live in California. Caroline’s daughter, Elizabeth C. Trescott (whose name was on the deeds) lived out her final 10-15 years living at the “Episcopal Church Home” an institution for the support of destitute females and orphan girls, on Laurens Street in Charleston.[33] Elizabeth C. Trescott died at the Church Home in 1875 and was buried in an Episcopal Church-owned lot in Magnolia Cemetery.[34] Just an interesting side-note- a few months after purchasing the Trescott House, in December 1852, a bill was enacted by the South Carolina legislature to incorporate the “Church Home” in Charleston, with William Patton being elected as one of its board of directors.[35]

The Trescott House for sale in 1851. -Highland Messenger, Asheville, NC, August 6, 1851, p. 3.- North Carolina Newspapers-

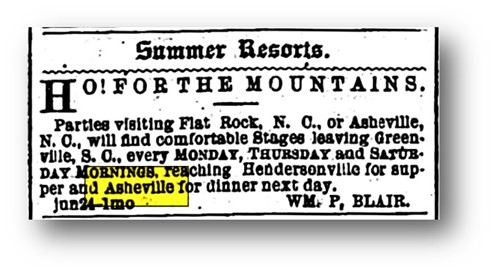

William Patton “of Charleston” was a cousin of the Asheville Pattons. William Patton was born in Wilkes County, North Carolina in 1794 to Thomas Patton and his wife, Jane Shaw Patton. Thomas Patton and his wife had emigrated to America from Ireland in 1792, with help from his brother James Patton. Around 1807, James Patton moved his family from Wilkesboro to Asheville, NC. At that time, his brother Thomas Patton moved his family from Wilkesboro, NC to Bedford (now Coffee) County in Tennessee. Mostly likely William Patton, as a young boy, had moved with his family to Tennessee, but sometime before he was 20 yrs old, William moved to Charleston and became a prosperous merchant. Shortly after moving to Charleston, William Patton married Elizabeth Kerr, the daughter of Andrew Kerr of Charleston, SC. Patton eventually became wealthy as a factor, shipping-agent and wharfinger-even owning his own wharf, Patton’s Wharf (at the east end of Hasell Street).

“William Patton, of Charleston” -photo from: A History of Black Mountain, by S. Kent Schwartzkopf (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Division of Archives & History, 1985), p.37.

Asheville was not new to William Patton. Not only was his Uncle James Patton a pioneer settler of Asheville, but William Patton had received his schooling at the Newton Academy in Asheville. In later life, he would also often visit Asheville with his wife, whose sister, Henrietta Kerr had become the second wife of his first cousin James W. Patton in 1839.

By the time he bought the Trescott house in 1852, William Patton was semi-retired and had begun investing in property in Buncombe County. He had already (in 1838) purchased the William Gudger homeplace further east along the Swannanoa River where he built a large brick house named Swannanoa Lodge. Also, he had already purchased his “Black Mountain lands” which first consisted of 740 acres[36] of land along the North Fork of the Swannanoa River (purchased in 1845) at the base of Mount Mitchell, and later he purchased an additional whopping 16,000 acres, which included the top of Mount Mitchell (the highest peak east of the Mississippi River).[37]

Prior to purchasing the Trescott house, Patton and his family would stay at Swannanoa Lodge whenever they were up in Asheville, but after the purchase they switched their residency to the Trescott house, which Patton named “Azalea” for the beautiful azaleas that grew on the property. It was a left-over English tradition to give one’s house or estate a name. However, Azalea, with its picturesque name, would eventually be, for William Patton, a place of extreme grief and loss.

“Elizabeth Kerr Patton, of Charleston” -from: The North Carolina Portrait Index, Compiled by Laura MacMillan, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1963), p.175.

On September 9, 1854, barely two years after purchasing Azalea, William Patton’s beloved wife Elizabeth Kerr Patton died.[38] Elizabeth, who was 59 years old, died in Asheville at “Henrietta”, the home of her sister Henrietta Kerr Patton (wife of James W. Patton). She was buried in St. Michael’s churchyard in Charleston. Sadly, William and Elizabeth’s daughter (her mother’s namesake), Elizabeth Kerr Patton Roper had passed away in 1850, just one year after her marriage to Benjamin Dart Roper, Jr.[39]

The following summer (1855), no doubt prompted by his grief, William Patton made the decision to sell much of his Asheville real estate, including Azalea. In an advertisement titled: “COOL SUMMER RESIDENCES FOR SALE”, Patton announced:

“The undersigned, having become possessed of more property than he wishes to retain, and desiring to devote his whole attention during summer, to the improvement of his Black Mountain property, will sell that beautiful RESIDENCE, situated in a romantic nook on the Swannanoa River, two miles and a half Southeast of the village, with 20 acres of ground, mostly in woods, residue in a garden spot and clover lot. The house is modern built; 10 rooms, large and high ceilings; with it may be had standing furniture nearly all new, some bedding, cooking utensils, crockery, &c. The stable, carriage house, and all other outbuildings nearly new. A Plank Road runs from the village to the Swannanoa River, where there is a level drive on its banks for nearly four miles. This road passing in front of the house by the Swannanoa Gap, to Morganton, &c. and view of the Black Mountain.”[40]

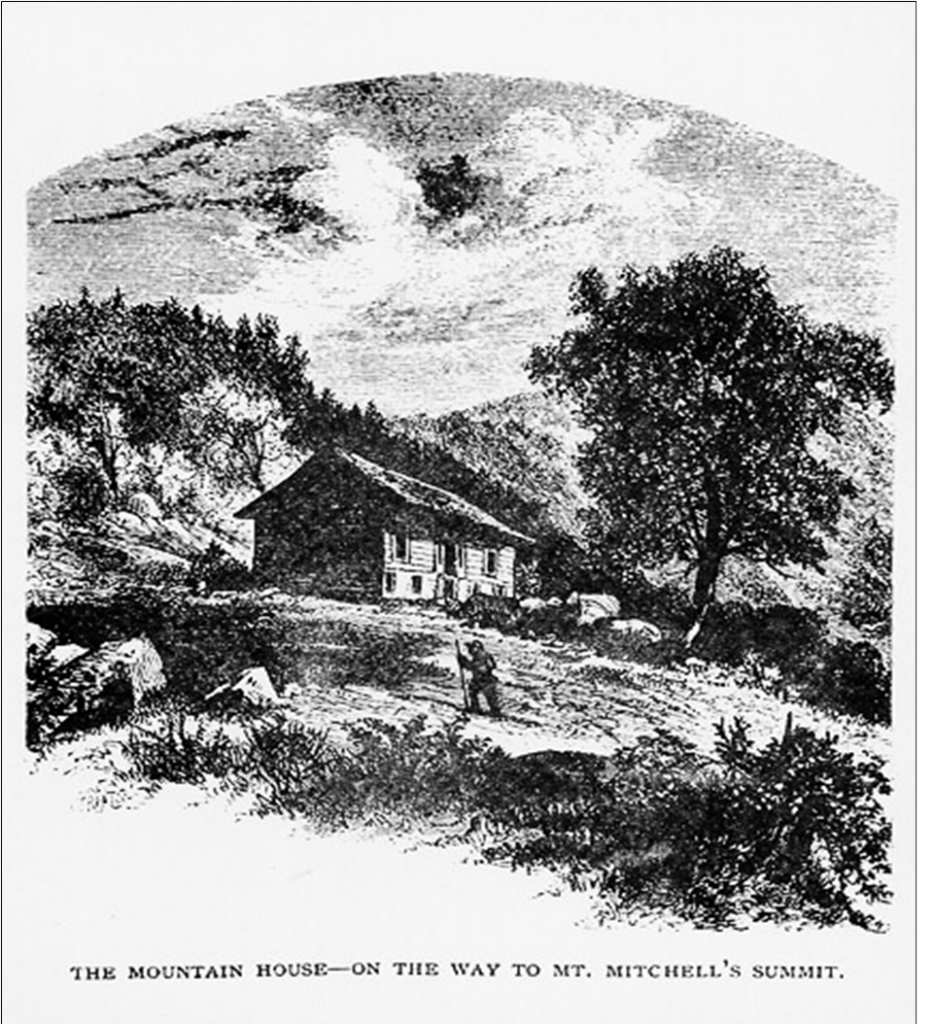

William Patton’s “Mountain House” near Mt. Mitchell. -Image H969-8- Buncombe County Special Collections at Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

The house never sold, which was fortunate for William Patton’s surviving family, which then only included besides himself, his daughter, Jane Patton Cheesborough and her husband John Cheesborough, and their four children: Edith, Elizabeth, William, and infant John, Jr. (a fifth child Jane was born in 1856). Nonetheless, Patton continued his ardent pursuit of the development of his Black Mountain Lands, which included improved trails and easy access to Mt. Mitchell. As part of his promotion of the Black Mountains, and to accommodate the tourists he hoped to receive, in the summer of 1853 he opened the “Black Mountain House” (later just called, “Mountain House”).[41] The “Black Mountain House” was described by contemporaries as being “built entirely of balsam” and located “…on the spur of the mountain four miles from the base at an altitude of 5510 ft.”[42] More specifically, the “Mountain House” was a one-and-a-half story house, framed and cladded (interior and exterior) with balsam wood, all setting on a raised stone basement. The recommended route to the “Mountain House” was to take the road along the North Fork of the Swannanoa River to Jesse Stepp’s boarding house at the foot of the mountain, “where guides and saddle horses can be procured for the 4 miles to the Mountain House and the 1-1/2 to 2 miles to the peaks”.[43] In the summers of 1854 and 1855, William Patton leased out the management of the “Mountain House” to Mrs. Sarah Garenflo.[44]

Greif upon Grief came in 1857. During the summer of 1857, William Patton, with his grief apparently assuaging, not only reopened the “Black Mountain House”, but he decided that year to act as its proprietor.[45] It was on June 27, 1857, that Dr. Elisha Mitchell, left the “Black Mountain House”, where he and his son Charles Mitchell had been resting overnight, never to return. Dr. Mitchell’s body was found on July 7th, “in a pool in the “Cat Tail Fork” of Caney River, about three miles below the top of the mountain, (the “Cat Tail Peak”) on the Yancey side.”[46] He had slipped and fallen to his death. William Patton’s return to Charleston in the Fall would bring even more unbearable sorrow. On November 8, 1857, Jane Patton Cheesborough delivered her sixth child, a daughter named Mary Anastasia Cheesborough. Sadly, Jane died two days later on November 10th and was buried at St. Michael’s churchyard in Charleston the following day. To add to the family’s immense sorrow, infant Mary Anastasia only survived for 17 days, dying on November 25th. Mary was buried in the grave with her mother, on November 26th.[47]

William Patton died just six months later, on June 27, 1858 at Warm Springs, NC (a health resort then owned and operated by his first cousins, James W. Patton and John E. Patton).[48] Though perhaps a bit melodramatic, the writer of Patton’s obituary evinces the depth of Patton’s sorrow: “The last years of Mr. Patton’s life were saddened by domestic tribulation, and the severances of those ties that can never be reunited on earth. The dark wings of the destroying angel overshadowed his dwelling, and left his hearthstone desolate.”[49]

In his Will, written in 1855, three years before his death, Patton bequeathed his properties (several lots, houses, businesses, and wharfs, in Charleston and Buncombe County) to his daughter Jane Cheesborough with the provision that upon her death they would all be the inheritance of her children. Though not named in his Will, Azalea was one of those properties, specifically described as: “…also twenty acres of land about two miles from the said town of Asheville with a three story wooden house and other building thereon situated on the Swannanoa River”.[50] Although house and property were later named in a probate inventory taken in 1859: “1st– The property known as Azalea with the household furniture”.[51]

Of course, William Patton was not the only person to suffer loss. His son-in-law, John Cheesborough, had not only lost his wife and infant Mary, but he had been left to care for six children (without any surviving grandparents)! But within two years he remarried to his wife’s second cousin, Louisa Matilda Patton of Buncombe County. Lousia Patton was born in 1836, the daughter of Thomas Taylor Patton and his wife Louisa Ann Walton Patton, and the granddaughter of James Patton of Asheville. Louisa Patton was 23 years old when she married 42-year-old John Cheesborough (and his six children) on September 13, 1859 at Asheville.[52] At the time, Louisa Patton had been living with her father and sister at “Pleasant Retreat” (the Patton farm) just a mile or so down the Swannanoa River Road from Azalea.

Due to John Cheesborough already having five children “who are amply provided for out of their mother’s estate”, and Louisa being “desirous to secure to her Father a suitable provision for his comfortable maintenance and support during life and to secure her estate to herself in the case of the death of her husband”, the couple had a pre-nuptial agreement drawn and registered on September 9th, four days before their marriage. The agreement gave Louisa complete control of her own “estate, real or personal” that she “may now have whether in possession or accession or may hereafter receive by gift, devise, purchase or inheritance”.[53] The agreement further stipulated that her estate was for the parties’ joint use during their lifetime, but that if her husband died before her, then her children would inherit her property; but that if she were to die before her husband, she would have the right to will her estate to “such person or persons as she may desire- In case of her death not bearing children.”[54] This agreement was ironic, in that not only did Louisa survive her husband, but she also bore him eight children!

John Cheesborough was the cashier at the Bank of Charleston when he and Louisa married, so despite marrying in Asheville, John and Louisa and the children immediately moved to Charleston, SC, into the Cheesborough house at the corner of Bull and Lynch (now Ashley) Streets. It was there that they were living in 1860[55] when their first child Clara was born. Although Clara was reportedly born in Asheville on July 23, 1860, the U. S. Census taker, just five days earlier, recorded her mother Louisa (and the rest of the family) living in Charleston at the Bull Street house. Mostly likely Louisa went back to Asheville to deliver her baby, and either she was not there during the census, but listed as a member of the household, or else she left for Asheville soon after the census taker’s visit!

Charleston may have been the worst place for the new Cheesborough family to set up housekeeping, as Charleston was very soon to become the epi-center of the outbreak of the Civil War. Not only was it at a convention in Charleston in November of 1860, that South Carolina formed a resolution and subsequently on December 20, 1860 was the first state to secede from the United States, and then it was at Fort Sumter, in April of 1861, just off the coast of Charleston, that the first shot of the war was fired. When war broke out in 1861, John Cheesborough sent his family up to Asheville to stay at Azalea. John Cheesborough’s position as Cashier at the Bank of Charleston, was not like a modern-day bank teller, but more as a bank manager or CFO, therefore it required him to remain behind in Charleston.

During the war years, John Cheesborough would keep in touch with his family at Azalea with frequent letters written to his “own dear wife”. Although most of the letters tell only of his coming home from the bank and sitting lonely in his drawing room, or going to the “club”, some of his letters tell of the wartime conditions in Charleston. In one letter written on May 21, 1862 he tells Louisa that: “The enemy has gone up Stono River in the rear of James Island and are shelling in every direction, but I do not apprehend that they will attack the City from that quarter, at least just now.”[56] A few weeks after Cheesborough’s letter, on June 16, 1862, the Confederate army attacked the Union forces on James Island (later known as the Battle of Secessionville) and thwarted the attack of Charleston. In the same May 21st letter Cheesborough wrote, not surprisingly that: “The City is now almost depopulated of women and children”.[57]

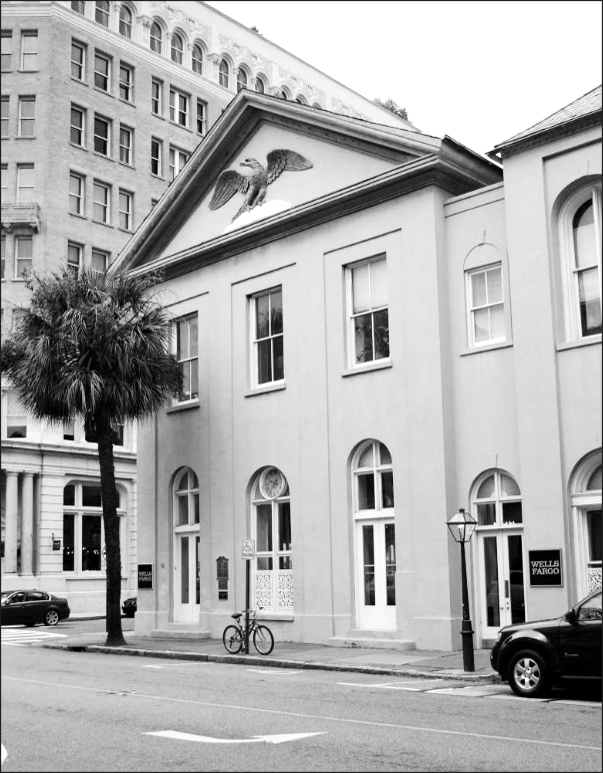

The original Bank of Charleston at 16 Broad Street, Charleston, SC. – Photographed by Brian Scott, September 20, 2011, The Historical Marker Database, – HMdb.org

The June 16, 1862 letter (mentioned above) was written by Cheesborough from Columbia, South Carolina, where he had fled to on June 5, 1862. In an earlier letter, dated June 6, 1862, Cheesborough writes to Louisa: “Here I am as you see a refugee in Columbia.”[58] Cheesborough further informs Lousia that he had taken a “special train” out of Charleston “last evening at ½ past 6 o’clock and arrived after a jolly time of it about 4 o’c. this morning”.[59] Cheesborough had closed the Bank of Charleston in Charleston and was moving the entire bank to Columbia. He also writes that he was living in “a delightful room over the bank”.[60] From a later report, it appears that Cheesborough not only remained in Columbia for the duration of the war, but at one point he had bought or leased a house on Laurel Street, where he even had his family come to live with him, until a dreadful day in 1865. On February 17, 1865, General Sherman’s forces attacked Columbia, and that evening the Cheesboroughs had to flee their home, “the house being in flames at the time”.[61] The war officially ended two months later on April 9, 1865. [62]“When South Carolina seceded from the Union in 1860, the Bank of Charleston had lent $100,000 to the state to support the new government. It would subsequently lend a total of $1.5 million to the Confederate government. The money was never repaid. The bank’s assets of $6 million dwindled during the war, leaving the institution insolvent by the time of the Confederacy’s collapse in 1865.”

This Rufus Morgan photo, c. 1871, shows “Springvale” shortly after it was completed. – Image P0057.107- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Wilson Library, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives

Although the 1866 Charleston city directory shows John Cheesborough living at the house at the corner of Bull and Lynch Streets, I believe he had already decided to settle the family in Asheville, as not only was Charleston in ruins, but it was heavily occupied by Federal soldiers and officials. It was in the summer of 1866 that Cheesborough’s wife Louisa and her sister Clara formerly partitioned their inherited property (the former James Patton farm). Clara took 600+ acres, including the old Patton house, which was all the land north of the Swannanoa River (now is all of S. Tunnel Road-Mall and other shopping centers), while Louisa took the 360+ acres south of the river (where is now Wood Avenue and the River Hills shopping center).[63] It was on Louisa’s property (one mile from Azalea) that the Cheesboroughs, shortly thereafter, built a new home which they named “Springvale”. By then John Cheesborough had eight of his eventual thirteen children to house! The family stayed at Azalea until the new house was completed.

Once settled in Asheville, John Cheesborough turned to farming on the Springvale property. Also, for a few years (1869-1874) he was a partner in a “cheese factory”. In May of 1869, just after Nicholas Woodfin had established his Elk Mountain Cheese Factory in the Beaverdam area north of Asheville, partners John Cheesborough, W. W. McDowell, Gilbert B. Tennent, Montraville Patton, Joseph Reed, and John Murphy, established the Swannanoa Cheese Factory in some outbuildings on the Azalea property.[64] Unlike the Elk Mountain Cheese Factory, which owned a herd of 200 cows, the Swannanoa Cheese Factory operated “on the Northern principle-every man who sends in milk from the surrounding region is interested. He will get cheese at the end of the season in proportion to the amount of milk to his credit.”[65] By the end of its first month, the factory had already produced “over 3,000 lbs.” of cheese.[66]

After Springvale was built, the Cheesborough family moved out of Azalea, and used the house as rental property, until 1880. In 1880, Jane Cheesborough, one of the older Cheesborough children, married Edward Issac Holmes. The young couple set up housekeeping, as they say, at Azalea. Jane and Edward Holmes lived at Azalea until their new house was completed at 60 Baird Street in Asheville, in 1884.

This photo, c. 1900, shows Azalea looking up from its driveway. Two Cheesborough siblings are sitting on the porch-identified as Minnie Cheesborough, and “a brother”. -Photo courtesy Laurel Kimbrough Ballard Thompson, Asheville, NC.

By 1884, the four oldest Cheesborough children (borne by Jane Patton Cheesborough), Elizabeth (Minnie), John Jr., William P., and Edith, were in their thirties and unmarried. I believe that it was at this time that the four moved out of Springvale. Edith went to live with her sister Jane Holmes on Baird Street in Asheville. The other three, Elizabeth(Minnie), John Jr., and William P., moved together into Azalea, which they had jointly inherited from their grandfather William Patton. Afterall, by 1880 there were fifteen people living in Springvale, John & Louisa and their thirteen children! For the ensuing two decades William P., John Jr. and Elizabth, lived together at Azalea. William P. acted as the patriarch of the household of siblings, as he had purchased additional acreage and had turned the property into a small income-producing farm. W. P. Cheesborough also became a local civic leader in the new town of Kenilworth which was established in 1891. Azalea was within the established limits of the new town. Both Willaim P. and John Jr. Cheesborough served as alderman and each even served terms as the mayor. W. P. Cheesborough won the mayoral election in 1893, in what could be called a land-slide victory, having received twice as many votes as any of his opponents! However, W. P.’s election as mayor of Kenilworth was quite unusual, as reported in the May 2, 1893 edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times:

“Probably never since the system of town government was adopted has there been a contest that is as comical from every point of view as the one which took place in the borough of Kenilworth yesterday. There were only four registered voters in the town when the books closed. These were Maj. W. E. Breese, Dr. W. C, Browning, W. P. Cheesborough, esq., and Rev. D. B. Nelson. Soon after the polls opened all of the gentleman named, with the exception of Dr. Nelson, voted, and it happened that each of the three received one vote from one of the others, for mayor. Dr. Nelson was out of town early in the day but came in on the 2 o’clock train. Whoever the Doctor voted for would be the next mayor, because he would receive two votes against the one vote of each of the other gentlemen; hence the interest to know his choice. If the Doctor had, in a humorous moment, voted for himself, then there would have been a tie of the whole business, probably necessitating a returning board from Washington to unravel the business. However, the Doctor voted for Mr. Cheesborough, and he was declared elected. The three defeated candidates will take their places on the board of aldermen. There was little excitement around the polls and absolutely no charges of bribery.”[67]

In 1890, Jane Cheesborough Holmes sold her interest in Azalea to W. P. Cheesborough and the other heirs for $2,000.[68] Then in 1891, two unmarried sisters from Charleston, Agnes and Lucia Campbell purchased 3 acres of the Azalea property from the Cheesborough siblings, and built a small two-story cottage, which they named “Asknish”, after a famous castle of the Campbell clan in Scotland.[69] The 3-acre site, which was adjacent to the Azalea house to the west, was the first bit of the 20-acre original Azalea site to be sold off.[70]

This 21st-century photo shows Asknish- built on the western portion of the Azalea property. -photo by author.

As the twentieth-century dawned, little did the Cheesborough siblings at Azalea know that a chain of events was about to begin that would forever affect their lives and the status of Azalea House. In the early morning hours of July 15, 1901, William Patton Cheesborough, at the age of fifty-one, died at Azalea.[71] This left John Jr., who was named the executor of his brother’s estate, and his two sisters Edith and Elizabeth (Minnie) Cheesborough as occupants and heirs of Azalea. But a year later, in December 1902, the doctor ordered John Jr. to go down to Orlando, Florida for the winter.[72] His sister Minnie went along to care for him. Sadly, John Cheesborough, Jr., did not even survive the winter, passing away at Orlando on February 27, 1903.[73] John Jr., in his Will, left his estate (valued at $6,000) to his sister Jane Cheesborough Holmes’ children (his nieces and nephews).

William Rhodes Ballard, Sr. and his wife Elizabeth Stone Cheesborough Ballard, with their dog, on the piazza at Azalea, c. 1910-1920. – Photo courtesy– Louisa Emmons, Morganton, NC.

The death of John Jr. left only Minnie and Edith Cheesborough as the owners and occupiers of Azalea, although Edith had already gone to live with their sister Jane C. Holmes at 60 Baird Street in Asheville. But a few months after John’s death, in June of 1903, the city of Asheville purchased the 4,100 acre Cheesborough property at the North Fork of the Swannanoa River near Black Mountain, NC.[74] The city was purchasing this land, which William Patton had willed to his grandchildren in 1857, to create a new watershed and waterworks for the city of Asheville. No doubt with the windfall from this sale, giving them the financial independence and support to provide for their upkeep, Minnie and Edith decided to sell Azalea. Fortunately, they were able to sell it to their half-sister, Eliza Stone Cheesborough, thereby keeping it in the family, though ending the line of William Patton’s heirs’ interest in the property. In September of 1904, Eliza Stone Cheesborough purchased the property from her half-sisters for $5,000 dollars.[75] Two months later, on November 10, 1904, Eliza Stone Cheesborough, in a “quiet wedding”, married William Rhodes Ballard of New York City.[76] After a brief honeymoon in New York, the newlyweds moved into the bride’s house (Azalea) in Asheville!

Billy Ballard, on the Swannanoa River Road, in front of Azalea on Easter morning 1917- Photo courtesy– Louisa Emmons, Morganton, NC.

The Ballards made Azalea their home, and it was there that they had a son William Rhodes “Billy” Ballard, Jr. born on October 10, 1910.[77]

A few years after the birth of William Jr., the Ballards began selling off portions (on the north) of the Azalea property to Kenilworth Park developers, Jake Childes, Roland Wilson, and E. G. Hester. Portions of modern-day Kenilworth, around Pickwick Rd., Kenilworth Road, Chiles Avenue, Ravenna Street and Dunkirk Road were originally part of the Azalea Property.

This 1966 aerial photograph shows Azalea and Asknish above the Swannanoa River Road. -NCDOT Historical Aerial Imagery, m0591_0878_t.jpg – https://www.arcgis.com/

At some point, the Ballards remodeled the house. The biggest change they made was to tear off the original low-sloped hip roof and replace it with a shingled gable roof, which included the addition of a centered gabled dormer on the front of the house. Interior bathrooms were also added, probably by the Ballards.

William Rhodes Ballard, Sr., at the age of seventy-three, passed away at Azalea on October 27, 1930.[78] Two years later, in 1932, William Rhodes Ballard, Jr. married Eloise Cole, of Asheville.[79] The newlyweds, then moved into Azalea, “temporarily with the groom’s mother”.[80] However, “temporarily” turned out to be almost fifteen years, in fact all three of William, Jr. and Eloise’s children were born while they were living at Azalea. A son was born in 1934, an infant who did not survive, was born in 1942, and then a daughter was born in 1943. Eventually, William, Jr. and his family moved out of Azalea, but Eliza Ballard continued to live at Azalea until her death in 1957. In those later years, Eliza would “take tea” every afternoon at “4’oclock” down the road at Springvale with her siblings, Mary, Septima, and Joe Cheesborough.[81]

Upon her death, Eliza Stone Ballard left Azalea to her son William Rhodes Ballard, Jr. By then, William, Jr. and his family had moved out of state, and so Azalea became their summer/vacation home. By the late 1970’s, twenty years after Eliza had died, the house was in bad shape, suffering from years of abandonment. Any preservationist knows that abandoned and neglected buildings decay and deteriorate at an accelerated rate. In 1978, the family decided to demolish the house. A few of the Greek Revival fireplace mantels and some of its older historic doors were saved but sold off. Fortunately, in 1978, the Historic Resources Commission of Asheville & Buncombe County, in conjunction with the Division of Archives and History, of the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources had just started the “Buncombe County Historic Properties Inventory” survey (which resulted in the publication of Cabins and Castles[82]). Although demolition had already started, and the surveyors were able only to get photos of the demolition, they were able to gather enough information to prepare record architectural drawings of the house as it was before demolition had begun.

Trescott-Azalea House being demolished in 1978. -Image N262-5, – Buncombe County Special Collections at Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

The loss of Azalea was a sad loss, as it was one of the few early nineteenth-century antebellum structures in Buncombe County to have survived into the late twentieth-century. Also, its unique design, as a Charleston Single-House transposed to the mountains, and its connections to Charleston (family and architectural ties) made it a significant piece of Asheville and Buncombe County’s architectural history.

The ruined chimney of Asknish, shown on the left in this post-Helene photo, is all that remains of the two houses that once occupied the Azalea property.-photo by author, 2024.

As a postscript: Had Azalea been still standing during the devastating storm and flood of September 2024 (Helene), it would likely have been severely damaged. The Asknish remains from its 2021 fire were swept away by the disastrous flooding. The ruined chimney of Asknish, is all that remains of the two houses that once occupied the Azalea property.

Sources

[1] 01/02/1891 (rec’d- 03/24/1891) John Cheesborough, Sr. Edith Cheesborough, Elizabeth P. Cheesborough, W. P. Cheeseborough, and John Cheeseborough, Jr. to Agnes M. Campbell 3 ACRES ADJ W P CHEESBOROUGH Db. 77/81. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[2] The Charleston Daily News, Charleston, SC, July 21, 1871, p. 3.

[3] This short biography of J. F. E. Hardy was composed from information gleaned from: Our Father’s Fields: A Southern Story, by James Everett Kibler. (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 1998), pp. 35-37.

[4] 05/27/1834 Ezekial McClure, Master of Equity (for the Heirs of William Foster, Jr.) to James F. E. Hardy

SWANNANOA RIVER 320 ACRES Db. 19/182. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds. This parcel was the northern half of the original 640 acre land grant to William Forster, Sr. William Forster, Jr. inherited this parcel north of the Swannanoa River from his father, and the southern half, south of the river, was at that time inherited by his brother Thomas Foster (who had dropped the ‘r’ from his surname).

[5] 07/18/1844 (rec’d 01/17/1845) James F. E. Hardy to Elizabeth C. Trescott SWANANNOA RIVER 20 ACRES Db. 23/112. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[6] Notes from the “Azalea” (Trescott House), Historic Sites Survey, State of North Carolina Division of Archives and History, n.d.

[7] Charleston Courier, Charleston, SC, October 12, 1847, p. 2.

[8] Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, SC, December 31, 1814., p. 2.

[9] See the 1816 Charleston City Directory- Charleston, South Carolina City Directories for the Years 1816, 1819, 1822, 1825, and 1829, by James W. Hagy. (Baltimore, MD, USA: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2002) p. 27.

[10] Dexter, Franklin Bowditch .Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College: 1802 – With Annals of the College History. United States, Holt, 1911, p. 549.

[11] Chancery Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Appeals of South Carolina, Jan. 1825-May 1827, By David James McCord. (Philadelphia, PA: Carey, Lea & Carey, 1827), p. 417.

[12] South Carolina, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1670-1980 for Edward Trescot, Charleston, SC- Wills, Vol 34-35, 1818-1826, pp. 41-41. -accessed through Ancestry.com.

[13] Chancery Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Appeals of South Carolina, Jan. 1825-May 1827, By David James McCord. (Philadelphia, PA: Carey, Lea & Carey, 1827), p. 418.

[14] Ibid.; See also a copy of the bond: “South Carolina, Secretary of State, Slave Mortgage Records, 1734-1859”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:ZYND-TZ3Z : Sun Mar 10 07:08:10 UTC 2024), Entry for Hagar and Caroline M Trescott, 13 Mar 1823.

[15] Ibid, p. 434.

[16] The Southern Patriot, Charleston, SC, May 8, 1829, pg. 3.

[17] 02/02/1841 (rec’d-07/30/1846) Samuel Chunn to Edward Henry Trescott ROSSES CREEK Db. 23/337. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[18] Asheville Messenger, August 20, 1841, p. 4.

[19] 09/04/1846 (rec’d-11/14/1881) Edward Henry Trescot to Steven [Stephen] Lee ROSS CREEK Db. 41/435. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds. This is the earliest land acquisition of Stephen Lee in Buncombe County, and I believe it became his “Mountain Home”-his home and academy. This deed was not recorded until 1881 and therefore required the evidences of D. J. Cain and William Hume as to the validity of the handwriting of Edward Henry Trescot’s signature (by Hume), and that of Samuel J. Palmer (by Cain) who was one of the witnesses on the 1846 deed.

[20] JFE Hardy to “Miss Elizabeth C. Trescott of city of Charleston”- (20 acres) (Elizabeth Trescot is age27)

07/18/1844 (rec’d-01/17/1845) SWANANNOA RIVER 20 ACRES Db. 23 p. 112 “for the consideration of one hundred dollars…”.

[21] Mrs Wm Trescott in the 1820 United States Federal Census- ancestry.com

[22] W Trescot [M Trescot] in the 1840 United States Federal Census- ancestry.com

[23] E Clayton in the 1840 United States Federal Census- ancestry.com

[24] G W Shackelford in the 1850 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules- ancestry.com

[25] Charleston Fancy: Little Houses & Big Dreams in the Holy City. By Witold Rybczynski (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019), p. 14.

[26] 1850 U. S. Federal Census, Parishes of St Michael and St Phillip, Charleston, South Carolina, USA-dated November 9, 1850.

[27] 01/06/1850- Elizabeth C. Trescott to Mrs. A. Laborde of the city of Charleston 20 acres Swannanoa River) Db. 24 p. 336. “a bond of $1,190 to Mrs. Laborde… conditioned for the sum of $495…”. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[29] Directories for the City of Charleston, South Carolina: For the Years 1849, 1852, and 1855, by William James Hagy (Baltimore, MD: Clearfield Company, 1998/2000), p. 24.

[30] 02/05/1851 (rec’d-03/26/1851) Elizabeth C. Trescott to Mrs. C. D. Eason BOND Db. 24/433. “…Mrs. C. D. Eason of the same place, widow”, “a bond of $436…conditioned for the sum of $208…”-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[31] 09/10/1852 (rec’d-01/01/1854) Elizabeth C. Trescott to William Patton 20 ACRES SWANNANOA RIVER Db. 25/254. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[32] I believe her to be the “Mrs. Trescott” who is recorded in this death record: “South Carolina, Deaths and Burials, 1816-1990”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:HFPZ-4WN2 : Tue Mar 19 03:37:13 UTC 2024), Entry for Trescott, 7 May 1856.

[33] 1869 and 1872 Charleston City Directories list: “Trescott, Miss E. C., Laurens, opposite Wall”.- This address matches the Episcopal Church which was then at 27 Laurens Street. That same house is still standing and is known as the James Jervey House, addressed as 55 Laurens Street.

[34] “South Carolina, Deaths and Burials, 1816-1990”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:HFP8-X9MM : Tue Mar 19 05:36:34 UTC 2024), Entry for Elisabeth C. Trescot, 21 May 1875. Also verified record with Magnolia Cemetery: “I have found in our original books the name of Elizabeth Trescoll, who was buried on May 22, 1875. She was 58 years old, married, and paralyzed. She did die on 8 Laurens Street.” -Marcia Beczynski, Magnolia Cemetery Trust.- Email message: From: Magnolia Cemetery Trust <magnoliacemetery@aol.com> Sent: Monday, January 6, 2025 8:20 AM, To: dslusser@helpsministries.org- Subject: Re: Elizabeth C. Trescott

[35] The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, SC, December 1, 1852, p. 1.

[36] 10/05/1845 (rec’d-02/04/1846) Samuel Davidson & James W. Patton to William Patton 740 ACRES SWANNANOA RIVER Db. 23/254. “First tract: 640 acres…other tract: 100 acres…”.

[37] 08/21/1850 (rec’d-10/01/1850) Albertus Burgin, Samuel Davidson, & James W. Patton to William Patton 16,”000 ACRES SWANNANOA RIVER Db. 24/309. “for One Hundred and Fifty dollars ($150)….five miles square containing sixteen thousand aces…”. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds. Note: the 16,000 acres also included his previous purchased tracts (740 acres) which were embedded within the “five-mile square”.

[38] The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, SC, September 15, 1854, p. 2.

[39] Matrimony Notice– “B. D. Roper, Jr. to Elizabeth, daughter of William Patton, Esq. All of this city.”, The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, SC, June 4, 1849, p. 2.; Funeral Notice: The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, SC, June 13, 1850, p. 2.

[40] “COOL SUMMER RESIDENCES FOR SALE”, The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, SC, May 31, 1855, p. 3.

[41] Advertised by “C. S. Brown, Contractor”, a stagecoach owner of Morganton, NC: Asheville Speculator, December 21, 1853, p. 8.

[42] The Salisbury Herald, Salisbury, NC, December 5, 1855, p. 2.

[43] “BLACK MOUNTAIN HOUSE.”, Asheville News, July 13, 1854, p. 3.

[44] Ibid.

[45] “THE BLACK MOUNTAIN HOUSE”, Asheville News, August 6, 1857, p. 2.

[46] Asheville News, July 16, 1857, p. 2.

[47] Forty Years a Rector and Pastor: The Anniversary Sermon of the Rev. A. Toomer Porter, D.D., at the Church of the Holy Communion, by Rev. Anthony Toomer Porter (Charleston, NC: Lucas & Richardson Company, 1894), p. 73.; And also obituary: The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, SC, December 2, 1857, p. 2.

[48] Obituary: The Charleston Daily Courier, Charleston, SC, August 4, 1858, p. 2.

[49] Ibid.

[50] “The Will of William Patton”, May 3, 1855, p. 2.- Ancestry.com. South Carolina, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1670-1980 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: South Carolina County, District and Probate Courts.

[51] “South Carolina, Probate Records, Bound Volumes, 1671-1977,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939L-V49L-C2?cc=1919417&wc=M6N4-9M9%3A210905601%2C211156401 : 21 May 2014), Charleston > Inventories, Appraisements, Sales, 1856-1860, Vol. E, p. 415 > image 237 of 321; citing Department of Archives and History, Columbia.

[52] The Charleston Mercury, Charleston, SC, September 19, 1859, p. 2.

[53] 09/09/1859 (rec’d-09/23/1859) John Cheesborough to Louisa M. Patton AGREEMENT Db. 26/516. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds

[54] Ibid.

[55] The National Archives in Washington D.C.; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M653; Residence Date: 1860; Home in 1860: Charleston Ward 4, Charleston, South Carolina; Roll: M653_1216; Page: 354; Family History Library Film: 805216

[56] Letter from John Cheeseborough to Louisa Cheesborough, dated “Wednesday 21 May 1862,” in the John Cheesborough Papers #1833, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Letter from John Cheeseborough to Louisa Cheesborough, dated: “Columbia 6 June 1862”, in the John Cheesborough Papers #1833, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Account of that evening from: Rules of the South Carolina Society: Established at Charleston, A.D. 1736, Chartered 17th May, 1751,

South-Carolina Society (Charleston, SC.: Lucas & Richardson, 1889), p. 15.

[62] “Bank of Charleston / South Carolina National Bank”, article by Caryn E. Neumann, online South Carolina Encyclopedia – https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/bank-of-charleston-south-carolina-national-bank/

[63] June 15, 1866 Louisa Patton Cheesborough deeded 356 acres south side of Swannanoa River Db 28 / p.104; and June 15, 1866 Clara Patton Murphy deeded 600 acres north side of Swannanoa River Db 28 / p.105 -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[64] “The Swannanoa Cheese Factory”, The Asheville News, July 1, 1869, p. 3.

[65] The Asheville News, May 20, 1869, p. 1.; See also: Asheville Citizen-Times, February 5, 1898, p. 6.

[66] “The Swannanoa Cheese Factory”, The Asheville News, July 1, 1869, p. 3.

[67] “FOUR OF THEM VOTED- And One Will Be Mayor and The Others Aldermen”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 2, 1893, p.1.

[68] Edward I. & Jane Cheesborough Holmes to William Patton Cheesborough (Swannanoa River 20 Acres) Db. 71/388 “…known as Azalea House…”. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[69] See: “Asknish: A Small Cottage with a Big History”, by Dale Wayne Slusser- https://psabc.org/category/architectural-tidbits/page/6/

[70] 01/02/1891 (rec’d-03/24/1891) John Cheesborough, Sr; Edith Cheesborough; Elizabeth P. Cheesborough; W. P. Cheesborough; and John Cheesborough to Agnes M. Campbell 3 ACRES ADJ W P CHEESBOROUGH Db. 77/81.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[71] “AFTER YEARS ILLNESS- W. P. Cheesborough Dies At His Home This Morning”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 5, 1901, p. 1.

[72] Asheville Times, December 18, 1902, p. 2.

[73] “DEATH OF JOHN CHEESBOROUGH JR.”, Asheville Weekly Citizen, February 27, 1903, p. 8.

[74] 06/08/1903 (rec’d- 06/22/1903) John Cheesborough, Sr., Exec.- of W. P. Patton Estate; Haywood Parker, Exec. of John Cheesborough, Jr. Estate; Janie Holmes; Minnie Cheesborough & Edith Cheesborough to the City of Asheville 4,173 ACRES SWANNANOA RIVER Db. 130/7. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[75] 09/15/1904 (rec’d- 09/16/1904) Edith Cheesborough; Elizabeth P. Cheesborough; & Haywood Parker, exec.-John Cheesborough, Jr. Estate to Eliza S. Cheesborough AZALEA Db. 134/537. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[76] “Cheesboro-Ballard”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 11, 1904, p. 2.

[77] William Rhodes Ballard Jr., in the U.S., Find a Grave® Index, 1600s-Current- ancestry.com

[78] “W. R. BALLLARD, AGED 73, DIES AT HOME HERE”, Asheville Times, October 27, 1930, p. 14.

[79] “MISS COLE IS THE BRIDE OF MR. WILLIAM R. BALLARD”, Asheville Citizen-Times, June 12, 1932, p. 16.

[80] Ibid.

[81] “Old Cheesborough Home Here Reflects the Charm of the Old South”, Asheville Citizen-Times, April 18, 1948, p. 23.

[82] Cabins and Castles: The History & Architecture of Buncombe County, North Carolina, edited by Douglas Swaim. (Asheville, NC: Historic Resources Commission of Asheville & Buncombe County, 1981).