by Dale Wayne Slusser

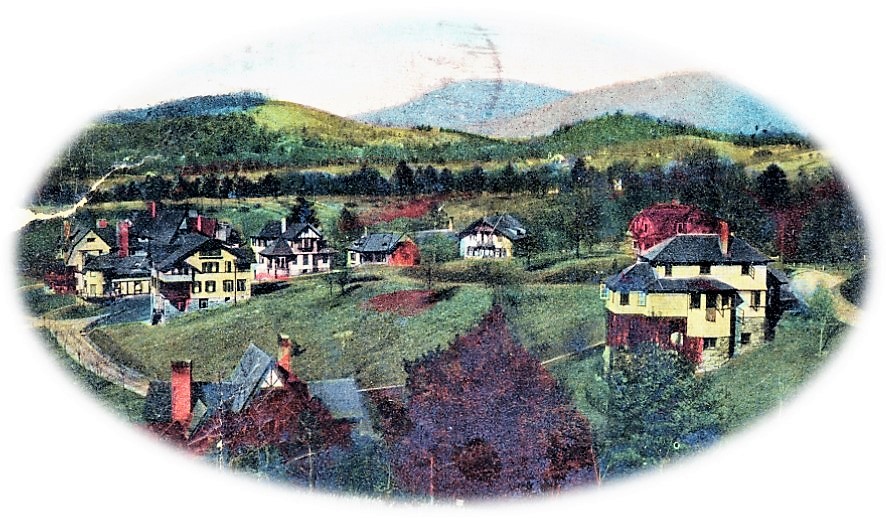

Today’s “Pocket Neighborhood” developers in Asheville would do well to study Albemarle Park, one of Asheville’s earliest planned residential developments. William Greene Raoul, a railroad executive from Georgia originally purchased the 34-acre Deaver farm on North Charlotte Street in 1886 as a summer retreat for his family. But a decade later, in coordination with his son Thomas Wadley Raoul, and with the professional aid of architect, Gilbert L. Bradford and landscape architect Samuel L. Parsons, William Raoul transformed the farm into a unique picturesque “cottage” development, that both maintained and maximized the site’s natural beauty and rustic character.

In 1886, Thomas Wadley Raoul was a young twenty-year old, working in the offices of S. M. Inman Cotthoon merchants in Macon, GA, when he was suddenly “mowed down” with tuberculosis. As he later recounted, “At this point Father took over”. Thomas was first sent off to the West, “to breathe it’s health-giving air”, but to no avail. He soon found himself shipped off to Asheville to regain his health, where his Father, as part of Thomas’s cure, put him to work cutting out and clearing the Asheville Place “with a view to the possibility of cutting it into building lots and selling it”. But following a suggestion by hotelier Col. Frank Coxe of the Battery Park Hotel, that they should build a boarding house, the Raouls decided to keep the property intact, build a boarding house/hotel and accompanying cottages to cater to the “summer people” who flocked to Asheville during the summer season.

To assist them in their new plans, William Raoul hired architect Bradford L. Gilbert of New York, who according to Thomas Raoul was his father’s “old friend”. William Raoul, as a railroad executive, had become acquainted with Gilbert who had designed several railroad stations for the Georgia Central Railroad. Gilbert had also had recently (1892) designed the Raoul family’s new home on Peachtree Street in Atlanta.

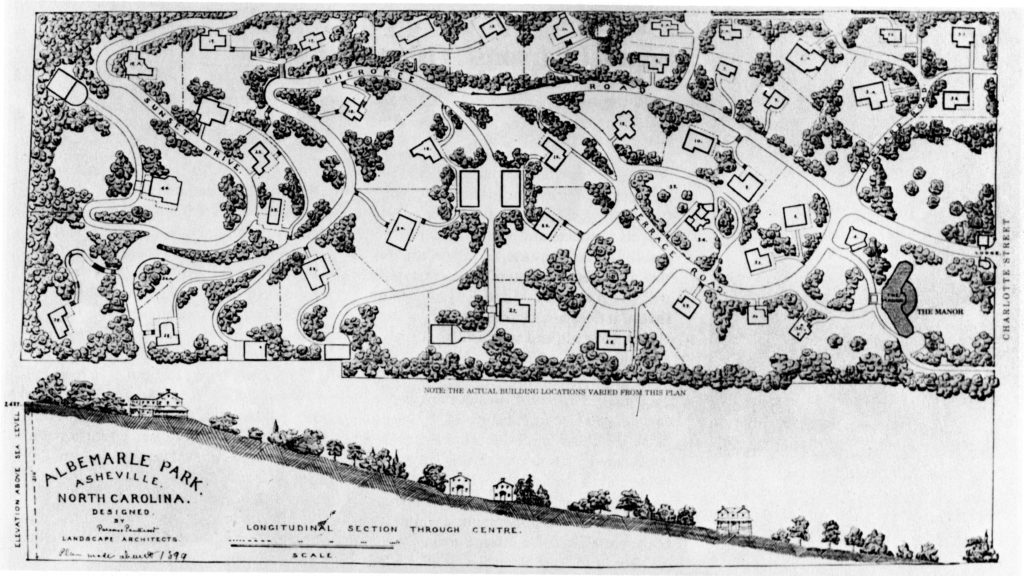

Gilbert quickly enlisted the assistance of noted landscape architect Samuel B. Parsons to layout the grounds in their new “residence park” (nineteenth-century term for “subdivision” or “residential development”). Parsons first apprenticed with, and then became a partner with, famed New York landscapist Calvert Vaux. After Vaux’s death in 1895, Parsons was appointed head landscape architect for New York City. As an interesting side-note, Parsons later became infamous for his accidental introduction of the fungus that led to the near extinction of the formerly widespread American chestnut tree. Ironically, the American Chestnut Foundation, whose “mission is to return the iconic American Chestnut to its native range” now has it national headquarters in Asheville!

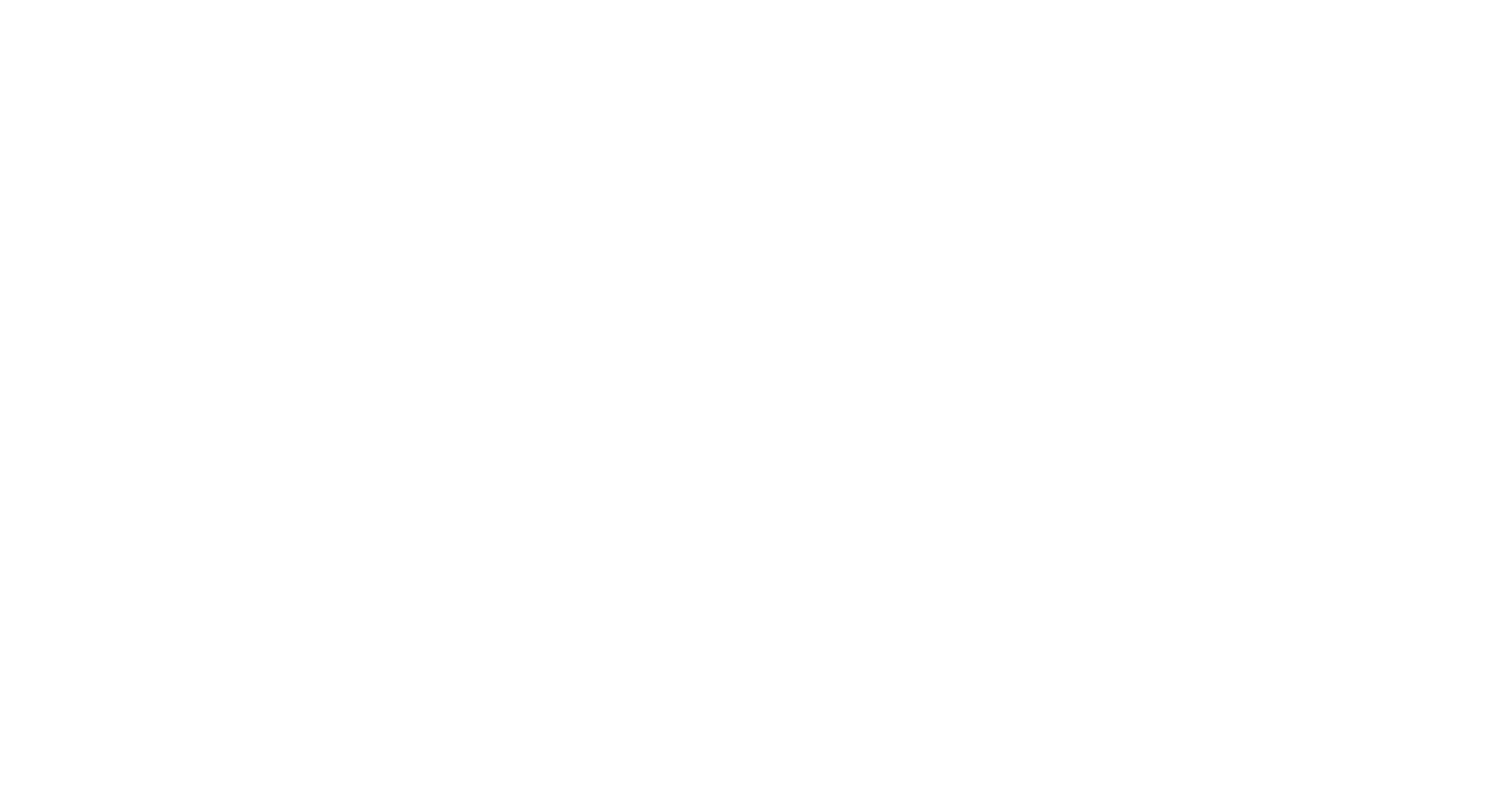

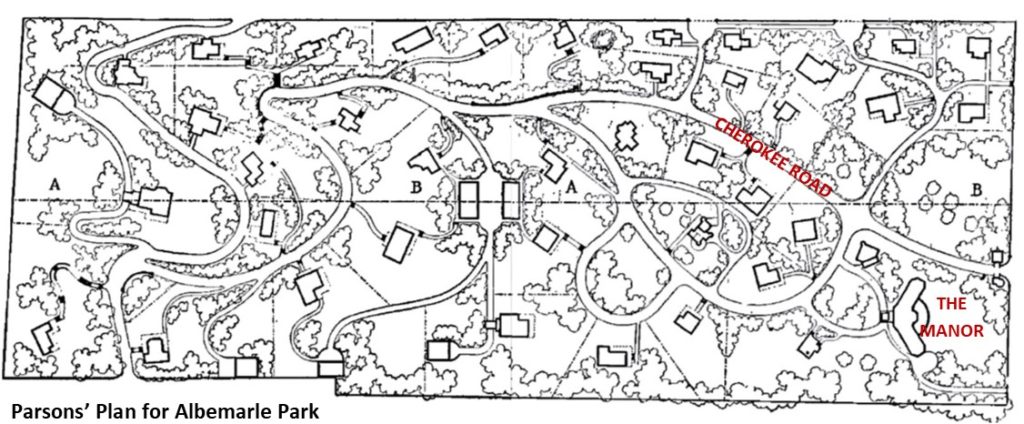

Parsons task to subdivide the property while still maintaining its natural beauty was a wonderful challenge for him. He later used the experience as an example to illustrate the design of “resident parks” in his 1899 book, How to Plan the Home Grounds. “The property in question,” he describes, “is bit of hilly country, in an inland town in the South, and is picturesque and charming to a high degree, being clothed in part by a beautiful variety of forest trees-oaks, chestnuts-etc.-and, at the same time looking out from its more open portions over a lovely mountain landscape.” Parson goes on to tell his readers that he was tasked to divide the property into 1-2 acre lots, and that each lot needed to be “specially adapted to securing the best outlooks and vantage points for the scenery”. “The problem was a knotty one,” he confessed, “and one which depended largely for its difficulty on the irregularity and picturesqueness of the contours. The place had fine views, and not much else that fitted it as a resident park”. Parsons also enumerates the “conditions that it was necessary to face” to design a suitable plan for the park. These included, a steeply sloped site that rose 300 feet from the bottom to the top of the site (a 29% grade), and the difficulty of siting the cottages so that they would be reasonably accessible albeit by “devious roads and paths”. Another difficulty was the control of water runoff caused by those “mountain torrents” which plagued mountain sites. Parsons’ solution was to design a brick gutter system to handle the storm water runoff, as well as calling for all the roads to be macadamized (paved) to keep them from washing out and to direct the water into the gutters.

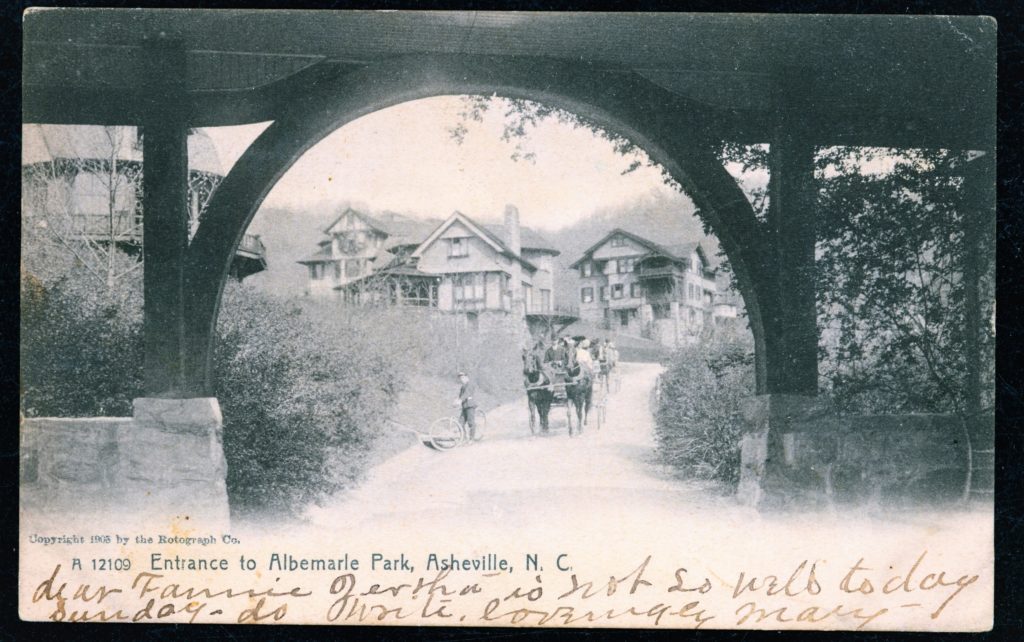

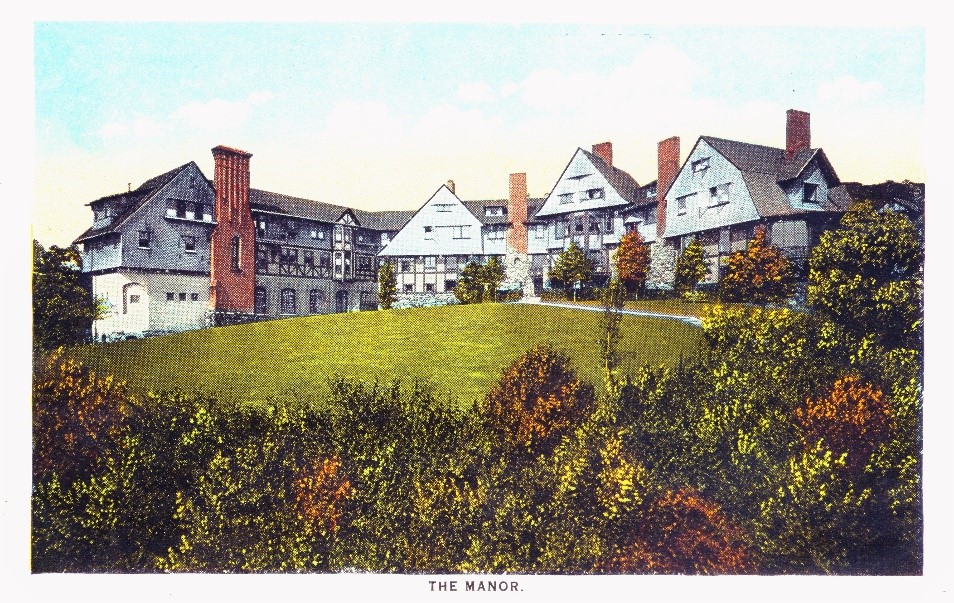

Parsons plan started with a stone entrance Lodge/Gatehouse at Charlotte Street (lowest part of the site) from which a main thoroughfare, later named Cherokee Road, rose first to a three-acre leveled plateau which was used as the site of the proposed Boarding house. Parsons described this area as a “little open meadow…where only is to be noticed any considerable stretch of turf for greensward”. It was on the northwest section, closest to the Lodge/Gatehouse that the Boarding house, named “The Manor” (as suggested by architect Gilbert Bradford) was sited. The first two cottages, Columbus and Clover were built flanking the drive into The Manor. Later an additional half-dozen cottages were built on the plateau.

Parson designed the main thoroughfare (Cherokee Road) to continue to rise up the hillside and connect to a network of circuitous roads, lined by divided lots, which followed the contours of the site. The whole resulted in a series of terraced (though cleverly disguised as such) homesites. Comparing Parsons’ plan with the modern-day siteplan, shows that his plan was closely followed, even though the site’s development took almost two decades, and was even subjected to a re-platting in 1913.

“The whole region is a mountain hillside,” writes Parsons, “with trees, shrubs, and vines largely clothing its slopes, and therefore the intention is evident everywhere of supplanting the work of Nature in the same Spirit, but with a distinct view of making tasteful and comfortable human homes within its confines”. Parsons goes on to describe that although the site is fairly wooded, that on some places, in order to carve out homesites, the existing trees needed to be supplanted, “every forty to fifty feet”, by new trees with such species as: American ashes, tulip trees, American lindens, pin oaks, chestnut oaks, wild cherries, and one or two kinds of maples and Oriental plane trees. Although Parsons called for some shrubs such as: itea virginica, spirea, forsythia, Eleagnus, Barberry, and Ligustrum to be used, the “crowning improvements of these plantations [homesites]” he states, “will be found in the vines and creepers that are found everywhere”. The vines and creepers were an excellent solution to cover the steep hillsides and road borders where grass would not grow. Parsons used English ivy as a substitute for turf in some areas, but found that the best replacement for turf in this Park was the “Michigan running prairie rose- rose setigera… as its growth is vigorous, its foliage healthy, and its bloom most profuse.”

Into the naturalistic and picturesque landscape designed by Parsons, architect Gilbert Bradford designed the Manor and accompanying cottages in an English Arts & Crafts style, reminding me of the work of Victorian British Arts & Crafts architect Norman Shaw. With the use of natural materials, stone, stucco, brick and wood posts and shingles, on the Inn and cottages, combined with Parsons use of ivy vines and creepers, the predominant image became that of a rural English Country Idyll. In the second phase of development in 1913, Thomas Raoul introduced the Adirondack-style into the design of several of the cottages. The Adirondack-style with its use of rustic natural materials compliments the rural English Country Idyll. A survey of each cottage and its design, however is not in the purview of this article, but perhaps may be a topic for further study.

Besides its picturesque design, Albemarle Park is also a unique “resident park” because of its multi-residential use design. Although it’s all residential use, it was designed (and still used) to include four types of housing: boarding (at the Manor); short-term (seasonal) rental of the cottages; multi-family housing; and single-family houses. This multi-residential use is evidenced by an early letterhead for The Manor and Cottages on which the byline read, “Cottages for Sale or Rent”. Another unique housing type featured in the early development were “housekeeping cottages”. These cottages were not only leased as fully furnished, but, according to an early promotional booklet, they also included groundskeeping. “The tenants of the cottages”, according to the brochure, “are relieved of the expense of a gardener, as the Company employs a force of men to mow the lawns, water and care for the plants and maintain the Park in the highest degree of cultivation.” Further amenities included, use of The Golf Club and the Albemarle Club, “as well as the proximity of The Manor where entertainments of different kinds are frequent, and where the occasional or regular meals may be obtained, freeing the housekeeper from the dangers of the “servant question.” Originally, there were four “housekeeping cottages” – Galax, Shamrock, Orchard & Milfoil-others were added later.

The success of the collaboration of architect Bradford Gilbert, landscapist Samuel B. Parsons, and the Raoul family to create Albemarle Park as a unique and picturesque residence park remains evident today, as not only does the Manor and most of the cottages remain, but the cottages continue to be desirable places to live, as most of the cottages (those under individual ownership) now command high prices when they are sold.

The Albemarle Park Manor-Grounds Association, a non-profit organization, was founded in 1988 to actively promote and facilitate the identification, preservation and documentation of the architecture, landscape architecture, and social and cultural history of Albemarle Park . The Association, through the support of its members and donors, works to rehabilitate and maintain the neighborhood’s historic features.

The Manor and the entire Albemarle Park (less three Charlotte Street cottages and the old clubhouse) are now on the National Register of Historic Places. Albemarle Park has also been designated by the City of Asheville as a local Historic District, one of only four in the city. As a local Historic District, any building or grounds improvements are subject to design review and approval by the Historic Resources Commission, insuring that Albemarle Park will maintain its unique and picturesque character for ages to come.

For more information see: albemarlepark.org

The Manor & Cottages:Albemarle Park- Asheville, North Carolina written and edited by Jane Gianvito Mathews and Richard A. Mathews (The Albemarle Park- Manor Grounds: Asheville, NC:1991).

Photo credits:

Albemarle Plan; Gilbert & Parsons portraits- albemarlepark.org

Gatehouse; The Manor; The cottages postcard- Pack Library, North Carolina Collection

Parsons Plan- S. Parsons, Jr. How to Plant the Home Grounds. (New York: Doubleday & McClure Co., 1899).

Modern-day Manor photo- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Asheville_North_Carolina.jpg