“Here lived Miss Agnes and Lucia Campbell, two very sweet and indigent Southern gentlewomen…”

By Dale Wayne Slusser

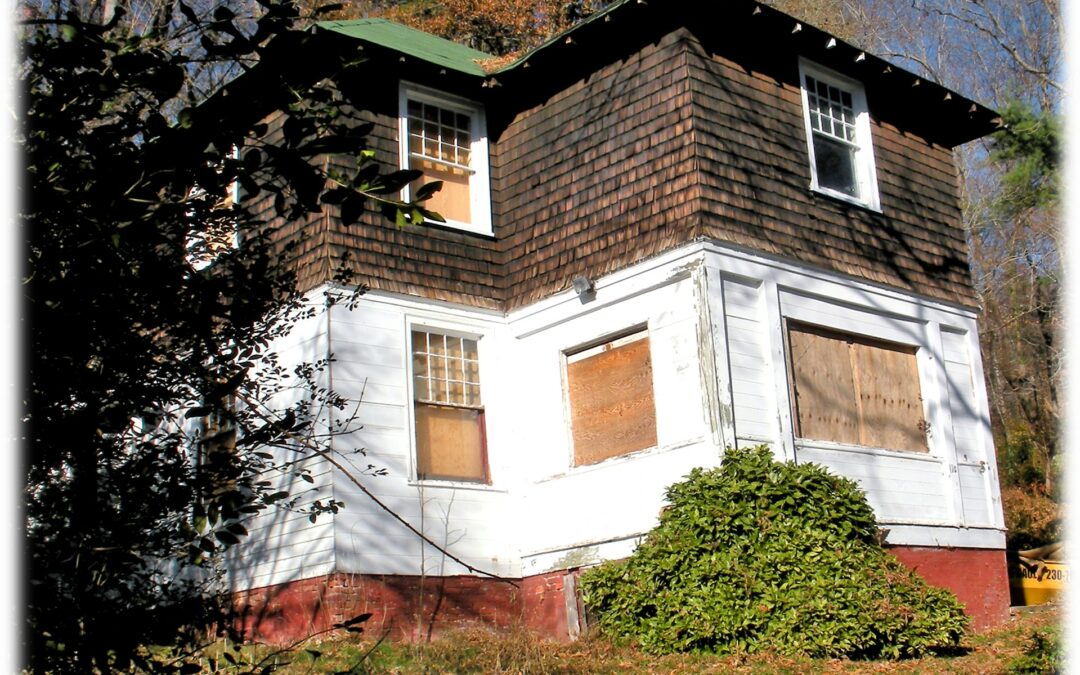

In 1889, northern millionaire George Washington Vanderbilt, began construction of his 250-room mansion, “Biltmore” on a hill above the southern bank of the Swannanoa River, just south of Asheville. But barely one mile from the Biltmore, in 1891, on a raise above the northern bank of the Swannanoa, a lesser-known impoverished southern elite, Agnes Morland Campbell from Charleston, South Carolina, began construction of a small, shingled cottage, which she would name, Asknish, after the ancestral estate of the Campbell clan in Scotland.

Asheville and Western North Carolina was known since the early 1800’s as a destination for tourists and those seeking respite and relief from a myriad of health issues. Prior to the Civil War, Asheville was a remote and somewhat inaccessible town situated on a plateau in the mountains of Western North Carolina. Although there were routes to Asheville from the east, the most accessible route was north-south via the Buncombe Turnpike, which ran from Greeneville, Tennessee to Greenville, South Carolina. Consequently, more of Asheville’s social development during the antebellum era is linked to Charleston and the low-country elites from South Carolina, rather than to the elites from eastern North Carolina or the northern States. In the 1830’s, the Charlestonian and low-country South Carolinian elites established their “summer colony” at Flat Rock, 22 miles south of Asheville, in Henderson County. The colony was founded by Frederick Rutledge and Judge Mitchell King. Judge King, who was a lawyer and Probate Judge in Charleston, first visited the French Broad River Valley of Western North Carolina in 1829 while on a survey trip to investigate a possible route to construct a railroad from the western inland rivers to the southern seaboard. Shortly thereafter he purchased land near Flat Rock and began building a summer home, “Argyle”, as a retreat to benefit his wife’s health. The Rutledges, another of Charleston’s wealthiest families, also bought land in the early 1830’s, near the Kings, and built their summer cottage, named “Brooklands”. Charles Baring and his wife Susannah Tudor Heyward were also among the founding families of Flat Rock, and soon thereafter the colony grew rapidly and soon included over 50 “cottages” built by notable families of Charleston, such as the Draytons, Lowndes, Elliotts, Pinckneys, Middletons and Trenholms. The high society of Flat Rock even included a “Count”. Count Marie Joseph Gabriel St. Xavier de Choiseul who was for many years the French consul at Charleston, established a summer residence in Flat Rock as early as 1836.

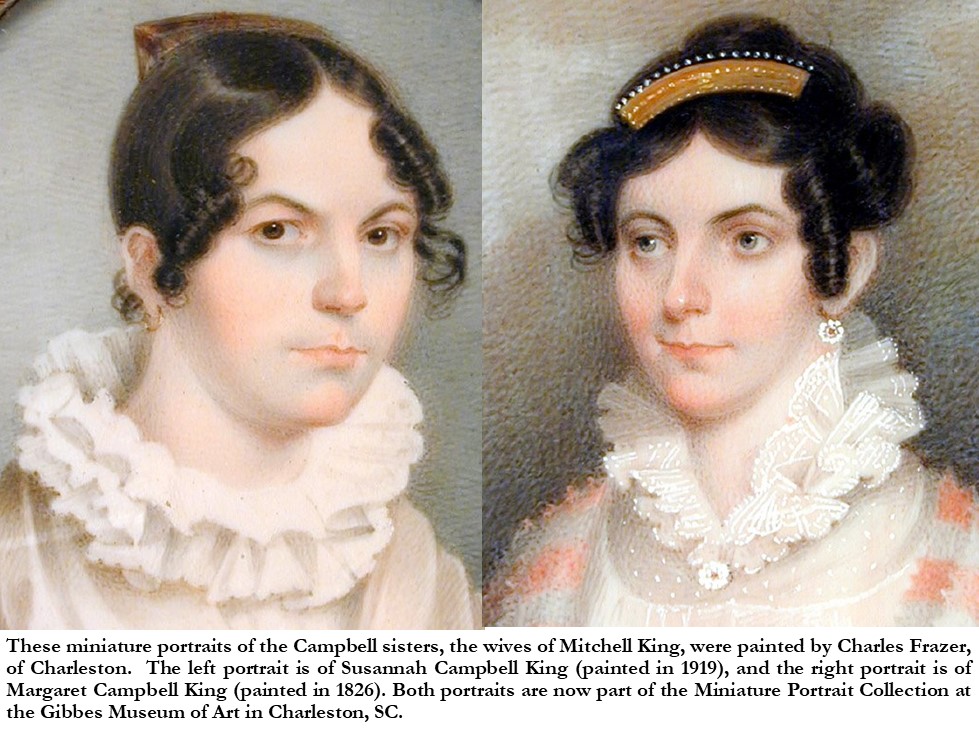

Agnes Morland Campbell, the builder of Asknish, had direct family connections to the Charleston colony at Flat Rock. Judge Mitchell King, one of the Flat Rock founders, was born in Craill, Scotland in 1793 with the last name of “Kingo”, which he shortened to “King” sometime after immigrating to Charleston in 1805. In 1811 Mitchell King married Susannah Campbell, the daughter of McMillan Campbell, and following her death he married her younger sister Margaret Campbell in 1830. These sisters were the daughters of McMillan & Henrietta Campbell, who had earlier immigrated to Charleston from Scotland. McMillan Campbell was the brother of Agnes Morland Campbell’s grandfather, Capt. Robert Henry Campbell. Both brothers, McMillan and Robert, had originally emigrated from Scotland to South Carolina, McMillan to engage in the import-export business, and the Captain as an officer in the British army. The Campbell brothers were the sons of Rev. Hugh Campbell of Rothsay in the Isle of Butte, and his wife Susannah Campbell, who was the daughter of Angus McIver Campbell of Asknish in Scotland.

Agnes Morland Campbell was an enigma, being once aptly referred to as an “indigent Southern gentlewoman”, and she can only adequately be understood by looking at her lineage and family connections, to which she clung to her entire life, and which (unfortunately) directed her life’s deportment. She was born in 1849 in Habana, Cuba to Robert Blair Campbell and his second wife, Caroline Morland Campbell. Robert Blair Campbell was then serving as the US Consul to Cuba (1842-1850) and had just recently married Caroline Morland, the daughter of John Morland, Esquire of Habana. Robert Blair Campbell was the son of Capt. Robert Henry Campbell, who served as a British officer during the Revolutionary War. Following the war, Capt. Campbell was awarded land in Canada for his service, but he exchanged it for land in Cheraw (Marlboro County), South Carolina, where he settled and established a plantation named “Ellerslie”.[1] Robert Henry Campbell, as mentioned earlier, was the son of Rev. Hugh Campbell of Rothsay in the Isle of Butte, and his wife Susannah Campbell, was the daughter of Angus McIver Campbell of Asknish.[2]

Angus MacIver Campbell of Asknish (Agnes Morland Campbell’s great-great grandfather) was from the MacIver-Campbell Clan having descended from Iver, son of Duncan, Lord of Lochow, who was son of Sir Archibald, second son of Malcolm of Lochow, by the heiress of Beauchamp in France, who was a daughter of the sister of William the Conqueror. Iver lived in the reign of King Malcolm IV (1153-1165). The descendants from Iver, to distinguish themselves from the other branches of the family of Argyll, were called MacIver, or son of Iver. The lands of Lorgachonzie and Asknish were given to Iver for his patrimony. Malcolm MacIver of Lergachonzie is fourth in the list of eleven barons whose names occur in the Sheriffdom of Lorn or Argyll, which was erected by an ordinance of King John Baliol, dated at Scone, 10th February, 1292. The family later bore the surname of Campbell and of the family of MacIver, being known as MacIver-Campbell of Asknish.[3]

Robert Blair Campbell, Agnes’ father, prior to his appointment as US Consul to Cuba, was a distinguished State senator and US Congressman. He inherited Ellerslie plantation from his father and became a wealthy planter while serving as South Carolina State senator (1821-1823 and 1830) and US Representative (1823-1825 and 1834-1837). In 1840, Robert Blair Campbell moved his family to his plantation in Alabama, from which he then served as a representative to Congress from Alabama.[4] Campbell returned to the US in 1850 from Cuba, and in 1853 was appointed US Commissioner to aid in the settlement of the boundary dispute between Texas and Mexico. The following year he was appointed US Consul to England. Although he was recalled as US Consul in 1861, he and the family remained in England until his death in 1862.[5]

Caroline brought her small family, consisting of herself, daughters, Agnes and Lucia, and son John, home to the US after Robert’s passing. The widow and her family first moved to her home state of Massachusetts, where they moved in with Caroline’s sisters.[6] In 1870, the family was living in Greenville, SC with none other than the de Choiseul sisters, Eliza and Beatrice.[7] It is unclear what the connection between the de Choiseul and Campbell families may have been, but no doubt it was either through their connections to Charleston, the King family, or possibly through Robert Blair Campbell’s diplomatic connections. By 1880, the Caroline Campbell family was living in Dorchester, SC, just eighteen miles from Charleston.[8] Although there were Campbell cousins still living in the area, Robert Blair Campbell’s Ellerslie Plantation had long ago been sold out of the family.

With the arrival of the railroad in 1880, the social order in Asheville drastically changed. During the post-war reconstruction era Asheville’s population (both permanent and seasonal) increased significantly, from 2,500 in 1880 to 12,000 by 1890 (with 100,000 yearly visitors). This increase of population and the resultant growth of Asheville continued to attract the old South Carolina elites (mostly from Charleston), however, like the Victorian British aristocracy, maintained their social-status because of their family names, but were now mostly cash-poor. To the social mix, now came the new northern moneyed elites, such as the Vanderbilts. They too were attracted to Asheville, both as a scenic and a health resort destination.

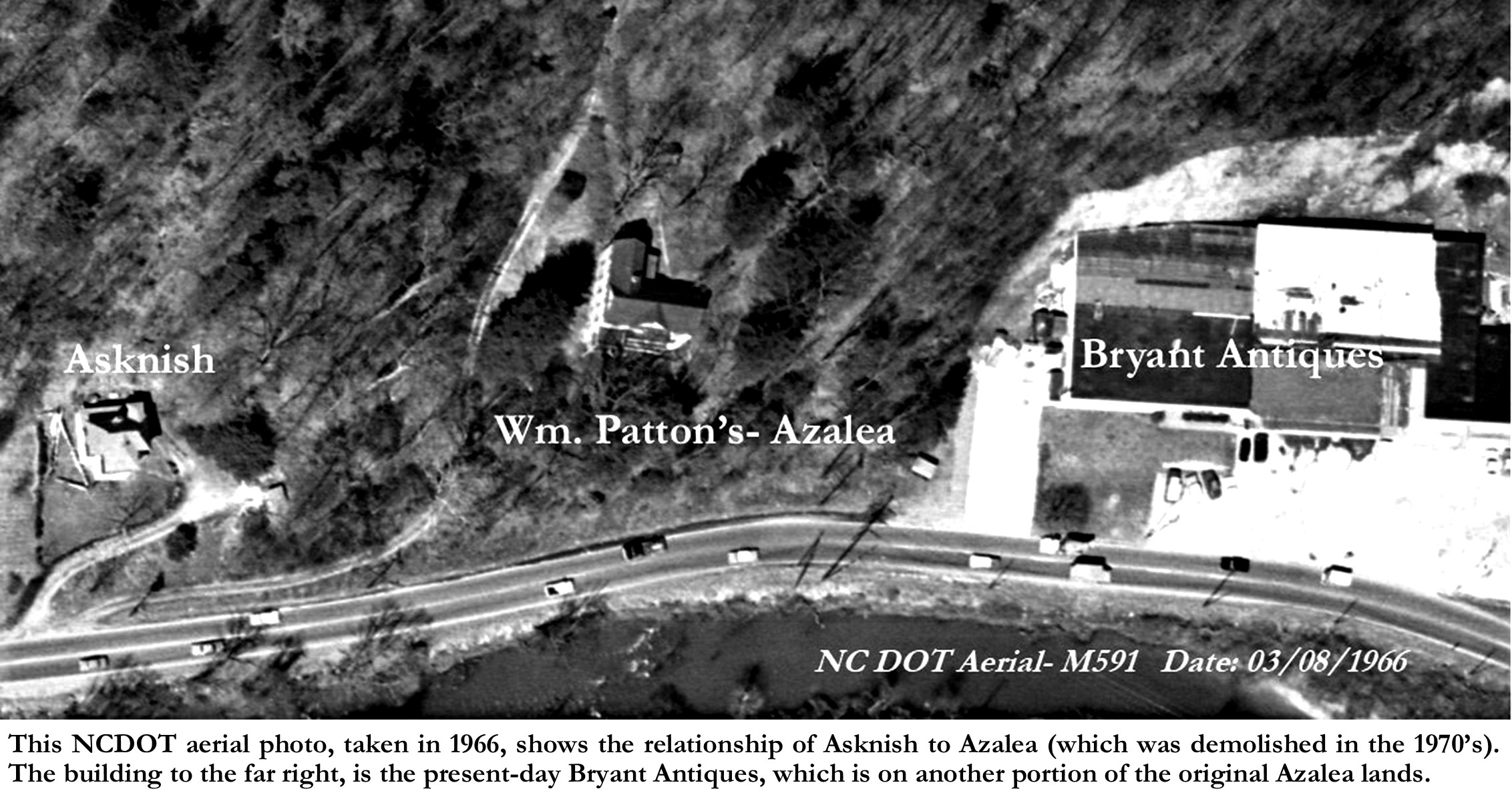

Caroline Morland Campbell passed away in Charleston in 1886,[9] and shortly thereafter her daughters Agnes and Lucia decided to move to Asheville, NC.[10] Agnes Morland Campbell purchased a three-acre sloped lot, on the northern bank of the Swannanoa River, from the Cheesborough family in January of 1891.10F[11] The property was, as the recorded deed states: “a portion of the original Azalea property owned by William Patton of Charleston”. In fact, the Cheesboroughs sold to Agnes Campbell, 3 acres on the western side of the original 20-acre Azalea property. We do not know how Agnes connected with the Cheesboroughs, but it would not be presumptuous to think that she knew them from her Charleston connections. But whether they had advertised the lot or whether Agnes approached them about selling off a small lot, we just do not know.

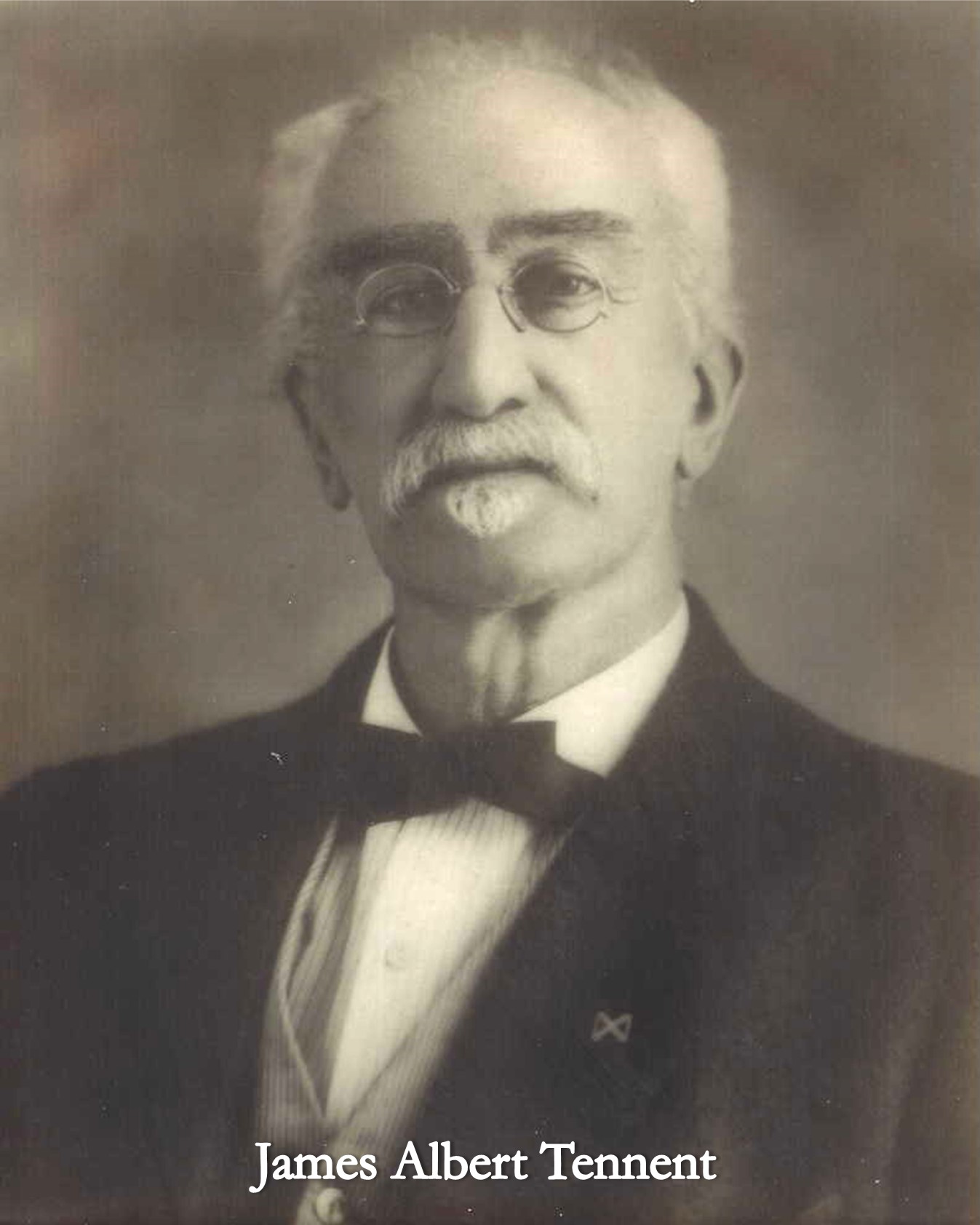

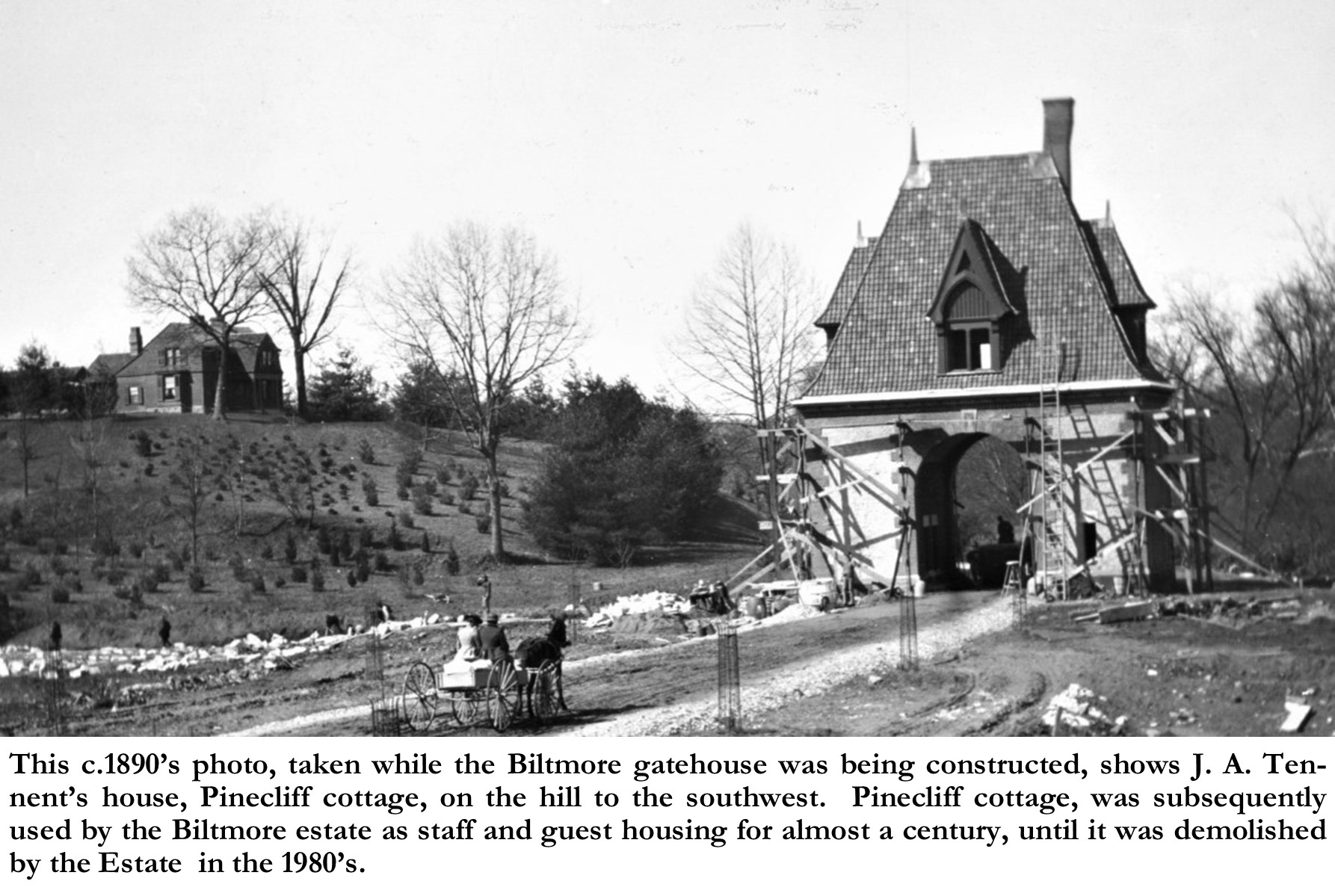

Judging from the entries in the ledger books of W. H. Westall, the building materials supplier, Agnes Campbell began construction of her new cottage in April of 1891, using Capt. J. A. Tennent as her builder/architect.[12] The official announcement came on May 21, 1891, when the Asheville Citizen announced that in addition to the contract for a house for J. B. Cain at Sulphur Springs, that Tennent had the contract for “a $2,000 house near Biltmore for Miss Agnes Campbell of New Orleans.”[13] Campbell had lived briefly in New Orleans, prior to moving to Asheville. The architect/builder, James Albert Tennent (who was born in Charleston) was a graduate of the South Carolina Military Institute and had served as a Lieutenant in the Confederate Army.[14] Tennent was the nephew of Gilbert Tennent who had moved to Asheville from Charleston at the start of the War and had built Antler Hall just west of Biltmore. James A. Tennent moved to Asheville in the early 1870’s and soon established his business as an architect and builder. His first major project was the building of the Buncombe County Courthouse on Pack Square in 1876, and later he built the sprawling brick and stone Asheville City Hall in 1892. During his long career (1871-1912), Tennent built and designed many notable residences and civic projects in and around Asheville.[15] At the time of the construction of Asknish, J. A. Tennent and his family were living in a house (designed and built by him) located about a mile west on the southside of the river. His house, later known as Pinecliff Cottage, sat just inside the Biltmore Estate Gatehouse.

Agnes’ small parcel and cottage was very modest compared with Pinecliff, Azalea, Antler Hall, and the other nearby houses on the river. The small cottage with only three rooms on each floor, reflected Agnes Morland Campbell’s limited income. Although her family, prior to the Civil War, were wealthy plantation owners, and although her father’s civil and diplomatic services meant that they lived in high society circles, the reality was that she and her sister were now cash poor. This is evident from numerous letters written to the Biltmore Estate offices from 1893 to 1904, where Agnes or Lucia would often appeal to estate manager Charles McNamee for leniency on their overdue accounts. In a letter written on September 23, 1897 to McNamee, Agnes makes a pleading appeal: “I think it due to the management of the Biltmore Store to tell you myself that I have been obliged, much to my mortification & regret, to let my account stand unpaid for several months, and also I am in debt for a small amount on the meat account. I am doing my very utmost to raise the necessary money to settle these accounts but so far without success- (and am nearly heart broken, the mortification is intense). Is it possible to have the time extended for a month longer? And as I must live, can I continue to get such few groceries as are absolutely necessary at the store on my book?”[16]

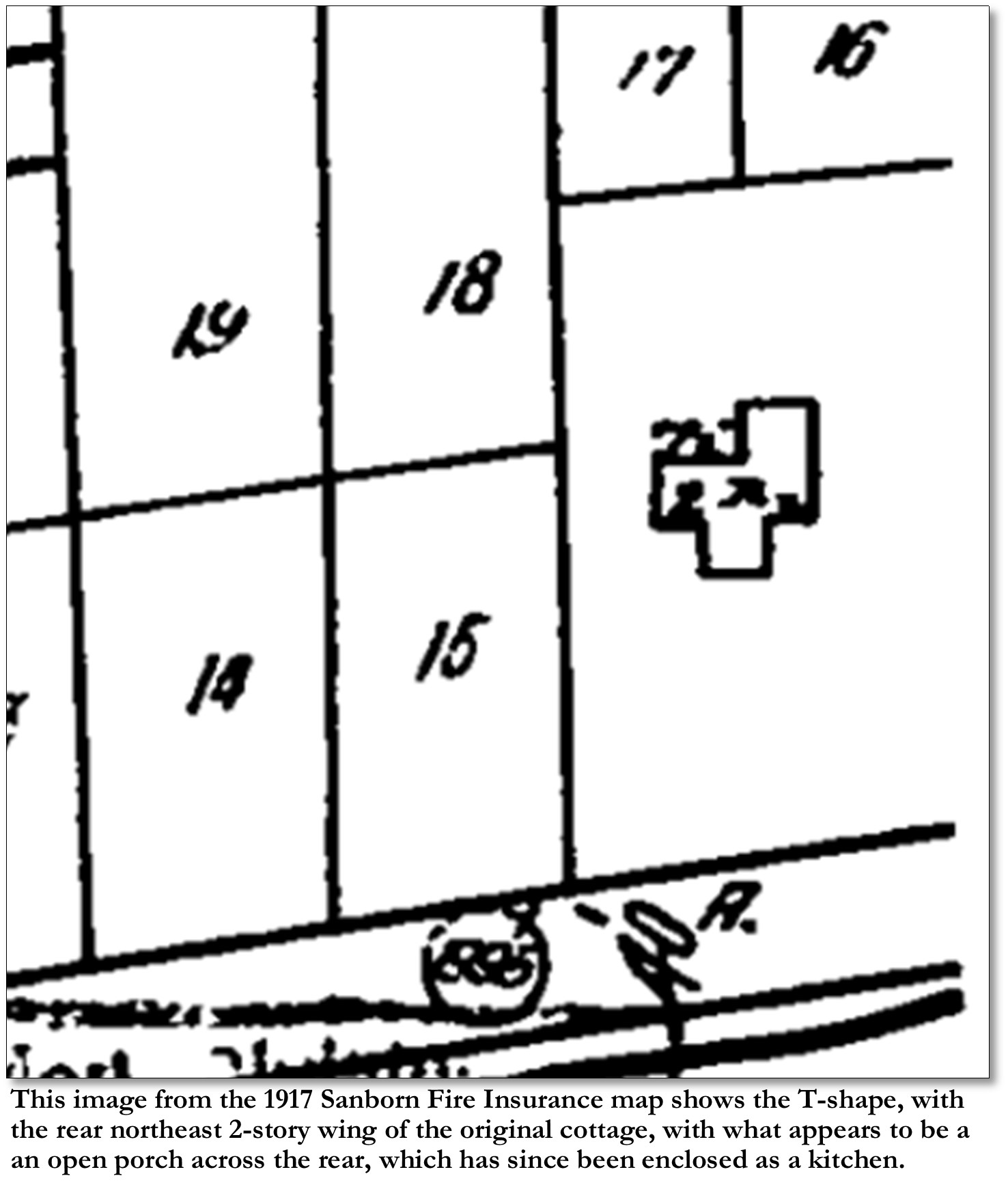

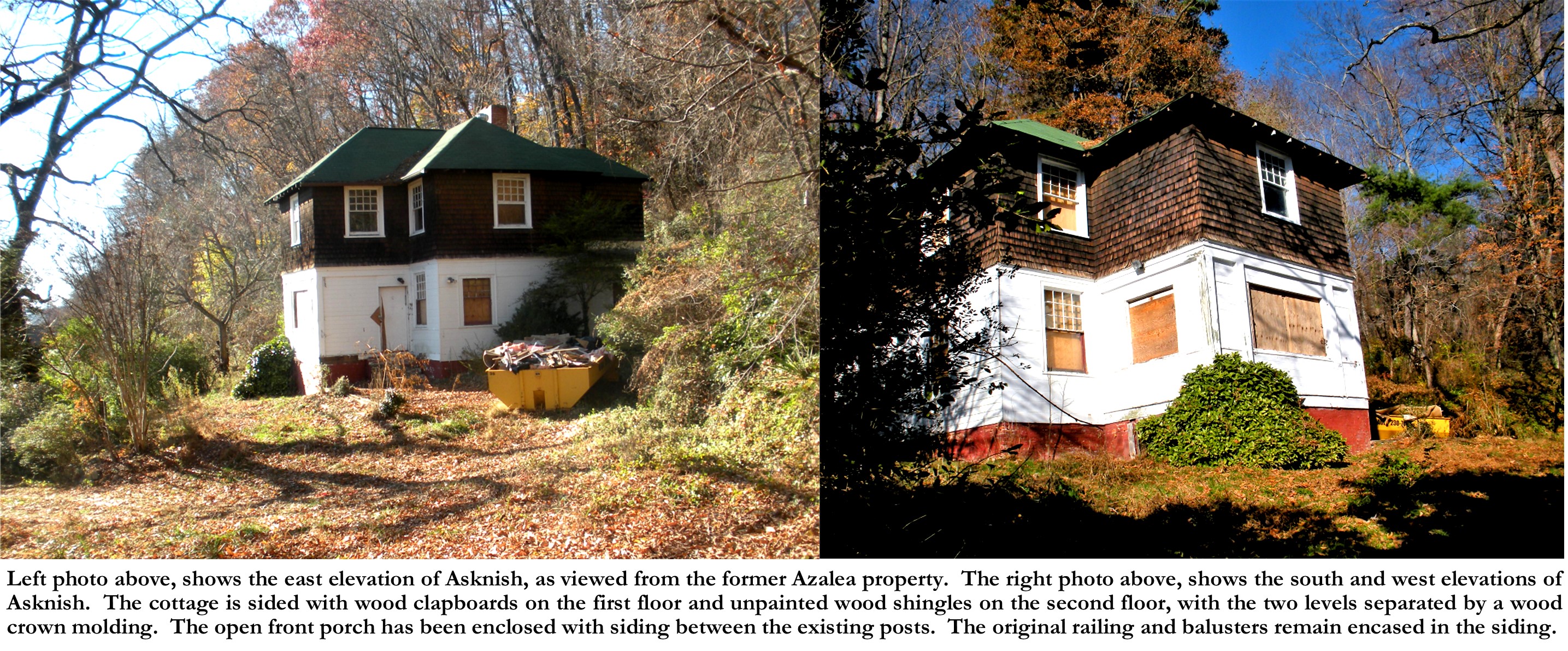

The overall configuration of the Asknish cottage is that of a two-story T-shape with the short leg of the T facing south overlooking the river and the top leg on the north side. The top leg of the T has three bays, with the center bay projecting out (south) eight feet. This center bay is comprised of an open entrance porch (now crudely enclosed-although the railings remain intact within the enclosed walls) with paired columns on the two outside corners on the first floor under a second-floor bedroom. The front porch is entered via three or four steps on its east end. The front door with its paneled bottom and half glass window above is the main entrance to the home after entering the (now enclosed) porch. The rear wing on the northeast corner of the house contains a bathroom on the second floor. A rear one-story section, which most recently functioned as the kitchen, appears to have been a later addition, there may have been (or in the location of) an original open porch. A narrow deteriorated modern-day wooden deck has been squeezed in between the rear wall of the cottage and the start of the sloped rear property.

Showing roots to the American Shingle style, the exterior of the house is sheathed in wood clapboards (mitered at the outside corners) on the first floor and sided with unpainted wood shingles on the second floor, the two levels separated by wood crown molding. Currently the first-floor siding has been covered over with a thin Masonite board paneled siding which could be easily removed. Typical of the style, the first few rows of shingles flare out over the top of the crown molding. The cottage sits on a brick foundation (crawl space) laid in a common bond pattern. An interesting feature is the use of staggered brick to create periodic openings which function as foundation vents. This reminds one of a similar practice used on nineteenth-century brick-end barns in central Pennsylvania. Moderately steep hip roofs with composition shingles and open rafters at the eaves surmount each section of the cottage. All the windows on the south, east and west elevations are double-hung sash windows with the twelve panes over one and appear to be original. The windows on the north side (and in the one-story addition) seem to have been altered, except for the second-story bathroom window which appears to be original (six over one paned).

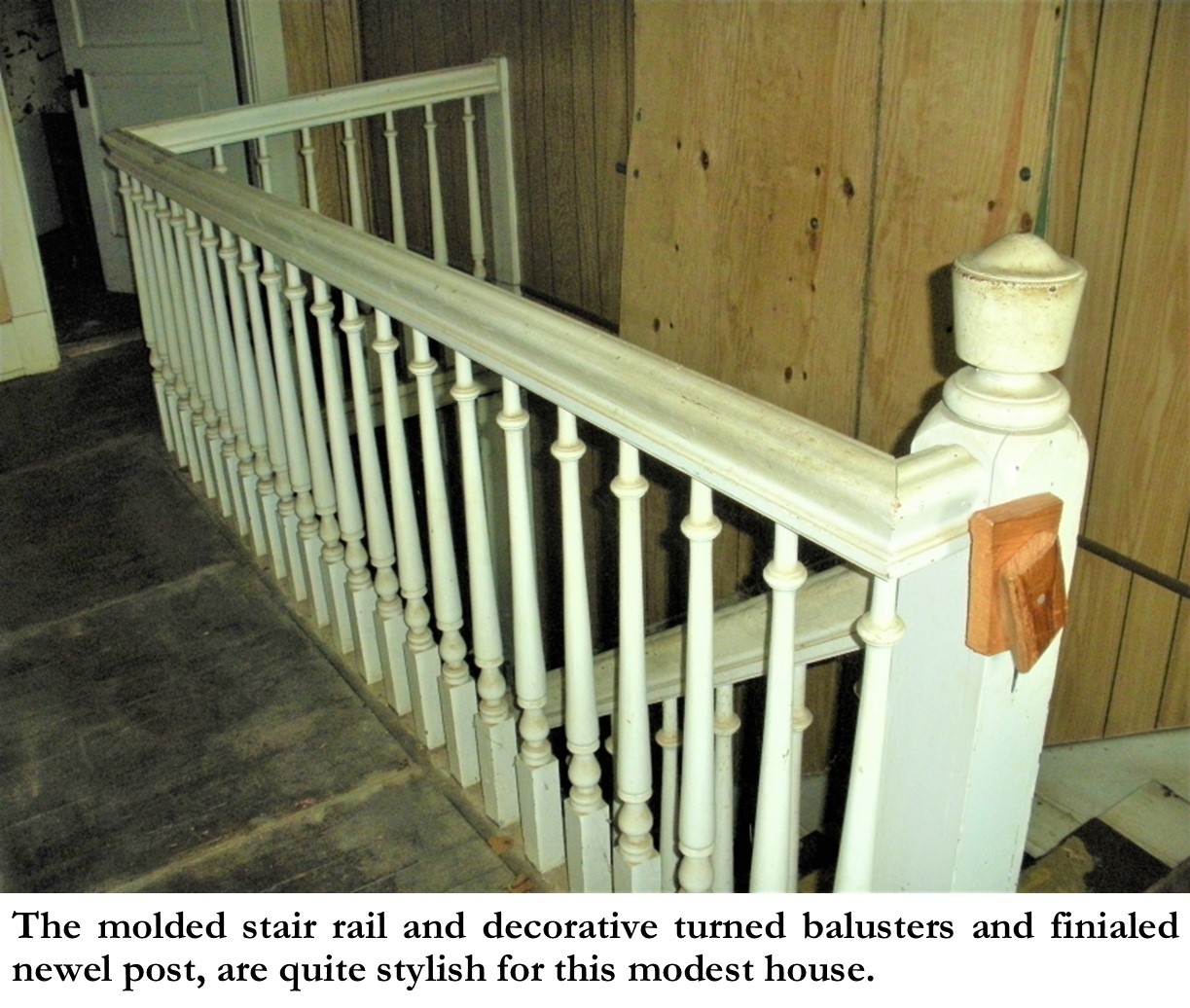

The small two-story cottage as designed by Tennant had only three rooms on the first floor. The two principal rooms in the front are the living room on the east and the dining room on the west. The third room is the kitchen at the rear of the house which currently spans almost the entire width of the two front rooms, but which originally appears to have been contained to a small wing on the rear east corner of the house. The door, window and baseboard trim are all simple and flat. Each of the front rooms has a corner fireplace on the north side straddling the center dividing wall between the living and dining rooms. The living room fireplace mantel is missing, but the dining room mantel is intact and appears to be original. The stairs to the second floor begin along the north wall of the living room and ascends five risers easterly to a landing before turning south and rising an additional eleven risers along the east wall. The original balusters and stair rails remain intact. The balusters have square bases with slender tapered posts separated by a turning at the top of the base and a molded ring at the top about two inches below where the baluster meets the handrail. The handrail is a simple molded rail about 2-1/2 inches wide and deep. The newel posts are simple boxed posts with a base and simple cap.

The second floor has three bedrooms and one bathroom. The bathroom is in the north rear wing of the second floor opposite the top of the stairs and is accessed by an open hallway which runs parallel to the stairs. The three second floor bedrooms are accessed from a transverse (east-west) hallway that runs perpendicular to the stairs. The first bedroom is on the south side of the hall in the projecting wing over the front porch. Two large windows (on the south and east walls) make this small room light and airy. Two layers of twentieth-century wallpaper cover the lath and plaster walls. A narrow closet on the north wall sits next to a plastered chimney (with an open thimble) which appears to have been built for a heating stove. The second bedroom is at the end of the hallway on the west side of the second floor immediately above the dining room. This bedroom also has two windows (south and west walls) with indications of a third window on the rear (north) wall which has been filled in (and may have at one time been changed to a door. This bedroom has an angled fireplace in its northeast corner directly above the dining room fireplace below. The fireplace mantel in this bedroom remains in good condition and is a duplicate of the dining room mantel. Although the fireplace opening has been closed off, the original cast-iron coal grate frame remains. A narrow closet for this room is in the southeast corner of the room adjacent to the closet from the front bedroom. The third bedroom is adjacent to the second bedroom to the east and across the hall opposite the first (front) bedroom. It has a closed off fireplace in the same configuration and location as the living room fireplace below. The mantle has been removed from this fireplace and the entire fireplace has been covered over with modern-day cheap wood paneling which covers the original lath and plaster walls. The floors of this room and the other two bedrooms appear to be pine flooring now covered with modern carpeting.

I suspect that Agnes had inherited some money from her mother, who had died in 1886, and that she used her inheritance to build her new cottage, but then was left with little or no regular income. Her financial situation continued to be a problem and was often the topic of her notes and letters to the Biltmore Estate staff to whom she often purchased supplies. She especially leaned on her fellow All Souls parishioner, Charles McNameee, both for material aid and fatherly advice. She enlisted his aid on numerous occasions (during 1897) while soliciting for a librarian position at the Library of Congress. On one occasion she wrote to McNamee: “I thank you for all your kindness & still hope and pray that we may get the appointment in the Congressional Library and am willing to do everything in my power to get it.”[17] Although she did not get the position in Washington, she was able to secure a position as Assistant librarian to Miss Emily Hatch (Head Librarian) at the Asheville Library Association on Church Street. Also in 1897, her sister, Lucia Campbell decided to sell her small house on Turner Street. Lucia like her sister also leaned on McNamee for advice on financial and business matters. When asking for his help in selling her house she wrote to McNamee: “The enclosed will explain the offer that has been made for my house, which I have decided upon accepting and in consequence of your kind offer to assist me I have desired Mr. Rutledge [her selling agent] to refer the gentleman to you, and trust in so doing I am not trespassing too much upon your kindness.”[18] It appears that Lucia had moved in with Agnes earlier and had been renting out her house for a few years prior to its sale.

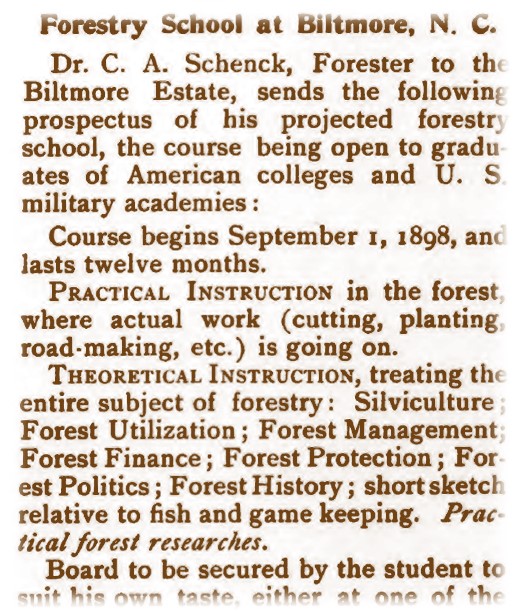

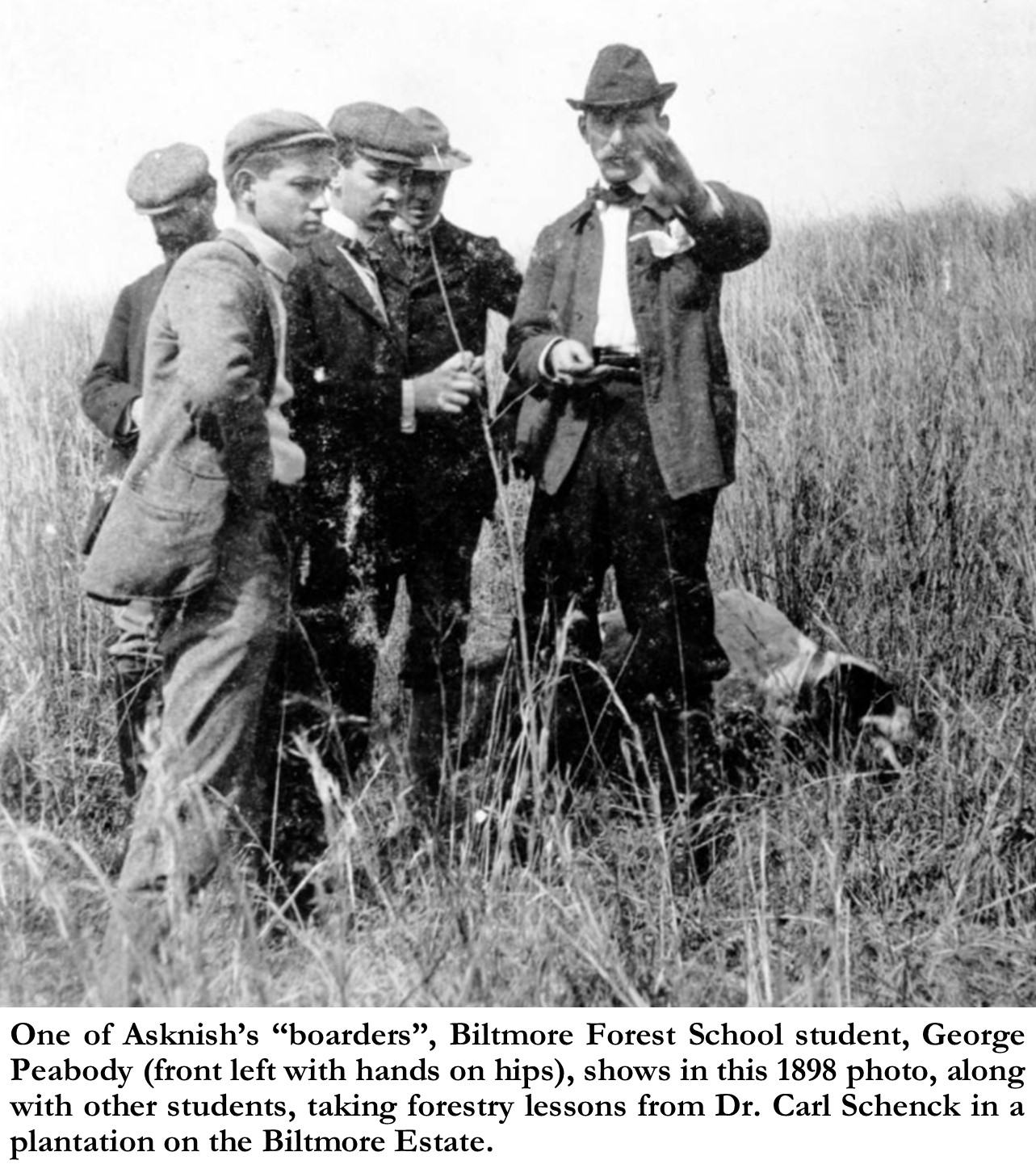

In an additional attempt to produce some necessary income, the sisters decided to use their cottage to board students of the newly established Biltmore Forest School. Dr. Carl Alwin Schenk was hired in 1895 to replace Gifford Pinchot as the head of the Biltmore Forestry Department. After observing his apprentices in the first years of his employment, Schenk felt the need for a school to train students in the rudiments of forestry and timber management. In 1898 Schenk opened the Biltmore Forest School, the first of its kind in America. Although other schools were soon to follow (programs at Cornell and Harvard), Schenk’s school had a distinct difference in that most of its teaching occurred “in the woods”, not in a classroom building on a college campus. The students’ tuition was $200, half of which went to Vanderbilt, the other half was used for hiring lecturers and buying textbooks.[19] The students were required to provide their own room and board. In an 1898 article advertising the start of the school Schenck writes that “Board to be secured by the student to suit his own taste, either at one of the numerous hotels or boarding houses at Asheville $8 to $15 per week), or at the house of a general foreman of the Biltmore Estate ($5 per week).”[20] Asknish in a was a perfect location for boarding students as it was only one mile from the Biltmore Estate office.

Agnes and Lucia were able to begin housing students during the first year of the school’s operation, as in an undated letter to Dr. Schenk, she writes: “Allow me to express our appreciation of your courtesy in sending us two of your students, Mr. Lamb and Mr. Peabody. We at the same time request that you will be so kind as to send us some more.”[21] We know from other sources that Frank H. Lamb and George Peabody were 1899 graduates of the school. Further in the same letter, Agnes informs Dr. Schenck of the pre-arrangements that she has made to accommodate the students in her small cottage: “I have arranged the upper rooms to accommodate four students, with a middle room as their little study, and feel that I can make them comfortable.”[22] I am assuming that two of the second floor bedrooms housed two students each and the third bedroom served as their study, which means that Agnes and Lucia may have arranged one of the downstairs rooms as their bedroom.

Subsequent letters over the next few years indicate that the sisters continued to house more students from the Biltmore Forest School-these included: Coert Dubois, John H. Burrell, Norman Mackenzie Ross, Benjamin Douglas and a “Mr. Drummond”. The sisters and their lodgers formed lasting friendships as later letters reveal. In a 1902 letter to Dr. Schenck, Agnes says, “I had a long letter from Mr. Ross, who expressed much regret that he would not have the pleasure of seeing you in Canada soon. A letter also from Coert Du Bois who seems to be very well.” [23] Years later, in an autobiographical essay, former student Coert Du Bois fondly recalled his stay with the Campbell sisters at Asknish:

“Mr. George Vanderbilt had got himself a baronial domain: An estate of five thousand acres or so surrounded the mansion or chateau (rather like that at Blois) hidden from the public eye by miles of winding roads through woods. At the entrance gates he had built the model village of Biltmore with houses of exposed timber beams and brick – old English style – with The Estate Offices, shops, a post office, and cottages for the help. The Swannanoa River ran through the village. A mile up the sandy road which ran along the river was a small white house with a barn alongside perched on a knoll. Here lived Miss Agnes and Lucia Campbell, two very sweet and indigent Southern gentlewomen whose family had fallen on evil days by reason of the depredation of the damn Yankees in the Civil War. It was here I was to live, off and on, for the next two years.”[24]

Agnes and Lucia Campbell had an ongoing relationship with the Biltmore estate. At the time of the building of “Asknish”, George Vanderbilt was establishing his estate across the river as an income-producing entity. Agnes often requested services from the estate. Not long after completing the house she sent (on “Asknish” letterhead) a request to Biltmore Estate Manager, Charles McNamee saying that she was “desirous of having rock for the drive to my little cottage, and venture to ask you if you would supply me from Mr. Vanderbilt’s quarry, and what the price would be.”[25] At other times she requested that the Biltmore Dairy deliver milk to her cottage.[26] Apparently she would also order kindling wood and even request “vegetables regularly from vegetable garden”.[27] One of her requests for wood gives us a picture into life at her little cottage. After requesting additional “stove wood”, in a letter to Mr. George Weston (Biltmore Farm manager), Agnes further requests that the wood be delivered by four horses or “come in two detachments” as the previous delivery had ended in disaster when the mules “were not equal to pulling it up our short but steep road, and most of it was emptied at the foot of the drive”, as the “wood driver wished to get his mules back for their dinner”[28] Agnes at an additional expense, had to later “employ men & cart” to bring the wood up to the house.

Apparently, the Campbell sisters did not always spend their winters at Asknish as evidenced in a letter from Lucia to Dr. Schenck asking: him the possibility of getting any more students for the term? “As otherwise,” writes Lucia, “I shall be closing the house for the winter, and preparing to rent it.”[29] Finally, in a final last-ditch effort to make ends meet, the sisters decided to lease an apartment, and later a cottage in the Biltmore Village and rent Asknish out to paying tenants. In June of 1903 they leased an upstairs apartment at “No. 6 Plaza”, and the following year they moved into the cottage at 7 All Souls Crescent.

In 1905 Agnes gave up her position as assistant librarian at the Asheville Library to accept a position as “branch librarian” at the Port Richmond Library in Staten Island, NY.[30] At that time Agnes and Lucia left Asheville never to return as permanent residents. Agnes’ financial difficulties were so severe by then that her beloved Asknish cottage was soon foreclosed on by her creditors. Agnes Campbell defaulted on a $2,000 deed of trust (loan) which she received from Mary Hoyt Granger in 1901.[31] In the May 1906 term of the Buncombe County Superior Court, it was ordered by the court that the cottage be sold to the highest bidder (“on the courthouse steps”) on July 30, 1906. Moses and Mary Hoyt Granger of Zanesville, OH were the highest bidders, and in September of 1906 the title was transferred to their ownership.[32] However, the Grangers immediately resold the property to local investors, James Stikeleather and C. Brewster Chapman.[33] The investors sold the property five years later, in 1911, to “Alice E. Reed of Buncombe County, and her husband, A. L. Reed.[34]

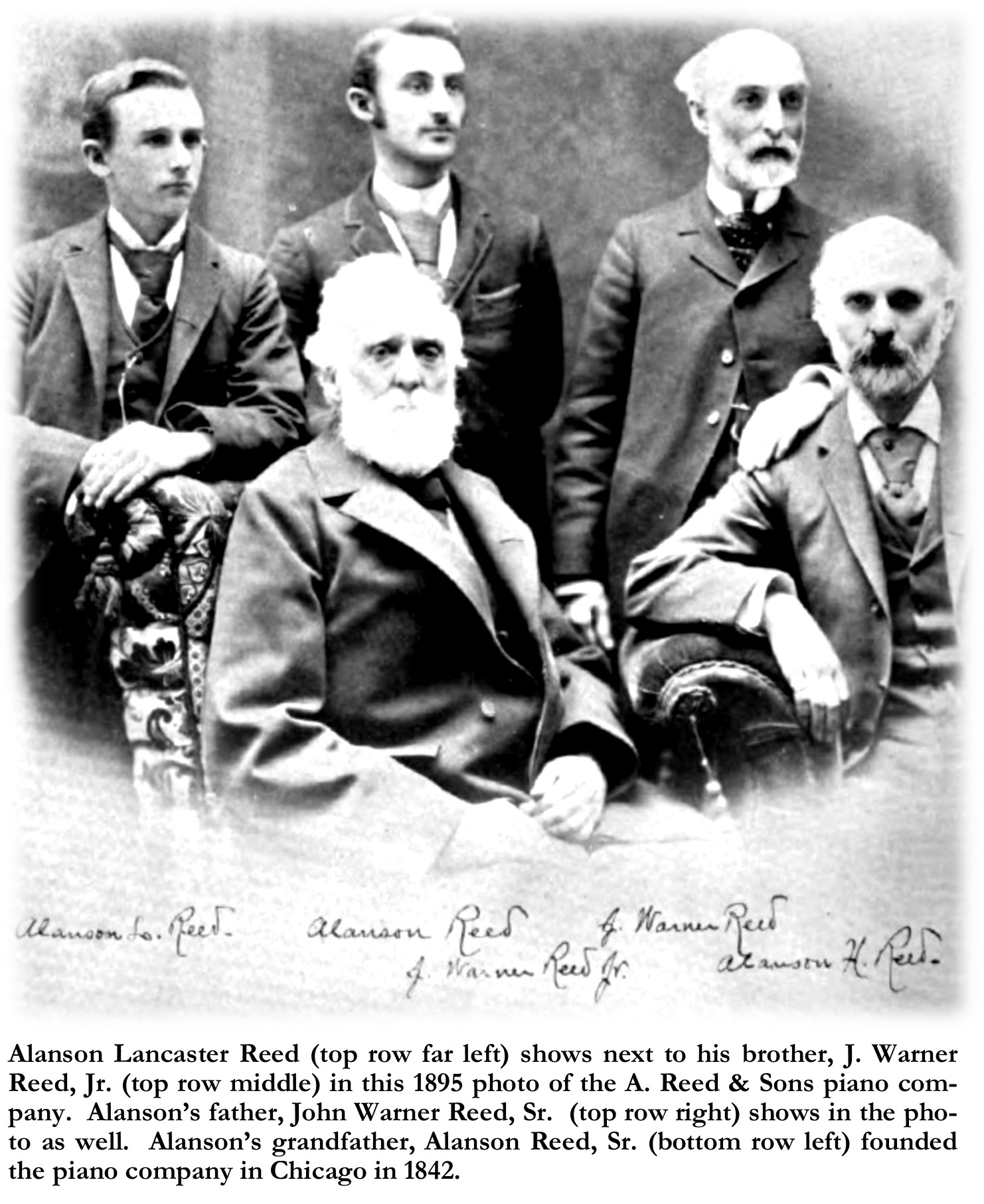

“A. L. Reed” was Alanson Lancaster Reed who was born in Chicago, IL on September 1, 1876 to John Warner Reed and his wife Virginia Lancaster Reed. Alanson’s grandfather (from whom he was named) Alanson Reed had founded “A. Reed & Sons” piano manufacturing company in Chicago in 1842. The Reeds sold their pianos through a trademark store named, “Temple of Music” in downtown Chicago. Alanson L. Reed, according to his own account, after graduating from St. Alban’s Military Institute in 1892, “in order to learn the business thoroughly he went to work in his father’s piano factory starting at the bottom. During the year 1898, he was sent out to travel for the firm, and continued “on the road” until 1901 when he was made superintendent of the factory.”[35]

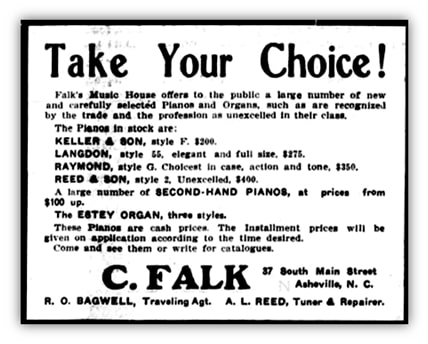

“Seeking a warmer climate than that of his northern home,”[36] Alanson Reed moved to Asheville in early 1904, and “established his office”[37] at Faulk’s Music House at 37 S. Main Street, where in addition to representing A. Reed & Sons, he established a piano-tuning business. He shortly thereafter met and married Alice Jackson in November of 1904. Alice Esther Jackson was born on June 16 1877 in Central City, Colorado to Dr. William Jackson and his wife Ruth Viola Loosely Jackson, and had moved to Asheville in 1898, with her mother, Ruth V. Brown and stepfather, M. O. Brown, half-brother Melvin Brown, and her brother W. W. Jackson. Sadly, M. O. Brown died in December of 1899, just 18 months after moving the family to Asheville.[38] Ruth Brown decided to remain in Asheville with her three children. But sadly, Alice’s younger half-brother, Melvin H. Brown passed away in 1901, at 18 years of age.[39]

In 1911, when Alanson & Alice Reed purchased the former Asknish house property, it included three acres which stretched from Swannanoa Drive up into the Kenilworth development. The Reeds moved into the house with their young daughter, Alice Frances Reed, who had been born in 1906. In 1913, the Reeds sold off an acre of land on the upper northern portion of their property to Kenilworth developers, Roland A. Wilson and E. G. Hester.[40] Then in 1917, the Reeds purchased an acre lot to the west of their property from L. F. & Susie Matthews.[41] According to the survey sketch in the deed, the new property was 100 feet wide (east-west) by 180 feet long (North-south), and included a flat meadow, just west of the house. Alanson Reed, in addition to his piano tuning business, had decided to also become a truck farmer-no doubt using the meadow as a small truck farm to produce market produce. In fact, I suspect that Reed may have leased the meadow before purchasing it, as in 1911, shortly after purchasing the Asknish property, the newspaper announced that “A. L. Reed of Reed’s farm, Swannanoa drive, reports plenty of raspberries for the past two weeks.”[42]

In the summer of 1922, Alice Esther Reed, suddenly passed away, leaving her husband and 16 year old daughter Alice Frances.[43] Just a year later, in November of 1923, Alanson Reed married Mrs. Fay Inez Davis.[44] However, the marriage only lasted barely three months, until February of 1924, when the couple divorced with Fay agreeing to a $6,750 settlement.[45] Then on September 9, 1926, Alanson Reed married for a third time, to Mrs. Flora L. Smith, a widow from Sarasota, Florida. However, it appears that Alanson Reed had a severe drinking problem, which may have been the reason for his short-lived second marriage. In November of 1926, a sensational front-page article, titled, “HUSBAND SLEPT IN BASEMENT IS WOMEN’S CHARGE-Mrs. Alanson L. Reed Asks Alimony Here From Millionaire”, appeared in the Asheville Citizen-Times.[46] “Alleging that her husband of a few days over six weeks was wont to come home and sleep in the cellar because of intoxication,” it was reported, “Mrs. Alanson L. Reed, has filed suit in the Superior court of Buncombe County against Alanson L. Reed, millionaire piano manufacturer of Chicago asking for $250 per month alimony without divorce.”[47] Mrs. Flora Reed further alleged that “her husband has been extremely cruel to her since their wedding on September 29, 1926, coming home in an intoxicated condition and spending most of his time in the cellar of their fashionable home at Kenilworth.”[48] The “fashionable home at Kenilworth” was not the Asknish cottage, as it has no cellar, but I believe the home that Flora and Alanson were living in was the home now at 77 Kenilworth Road. Alanson had purchased the 77 Kenilworth road home in 1923, shortly after he had married his second wife, Faye Davis Reed. Despite this sensational affair, it appears that Alanson and Flora either reconciled, or at least maintained a relationship for the remainder of their lives. In fact, according to the censuses and city directories, they both continued living together in the cottage on Swannanoa Road. Upon the death of Alanson Reed in 1933, all his property was granted to Alice Reed Hughes, with a life estate for Flora L. Reed. Flora Reed continued to occupy the Swannanoa Drive house (Asknish) until she sold her property interest to Alice Reed in 1936, and subsequently moved to Greensboro, NC, where she later passed away in 1944.[49]

In 1937, Alice Reed Hughes sold the property to Ellis & Elsie Frady.[50] The Fradys who lived on Hendersonville Road at Biltmore Forest, apparently bought the house as a rental income investment. The Fradys purchased the property along with Elsie’s sister Grace Frady Pennell as co-trustees under the will of Mary A. Frady (Elsie’s not E. C.’s) mother who died around 1918). In accordance with the will they, Elsie, husband Ellis C. and the Pennells, were given Mary’s property (after death of their father Noah) to be held by them for the support and maintenance of Mary & Noah’s disabled daughter (Elsie’s & Grace’s sister) Bertha Mae Frady. The will further stipulated that Elsie and Ellis were to keep Bertha in their home and care for her, and in exchange they were “to have complete use of all said property”.[51] In 1946, following the death of Bertha Mae Frady,[52] Ellis and Elsie Frady sold the Asknish property to Joseph & Nancy Parker.[53] However, the Parkers only owned the property for a few years, before selling it in 1952 to Edward L. & Lockie A. Phillips.[54]

Edward Leonard Phillips, and his wife Lockie Arrington Phillips were Madison County natives who had married in 1948. The Phillips moved into the house, then addressed as 297 Swannanoa Road, with their toddler son William “Bill” Stanley Phillips. Edward Phillips, a typical post- World War II hard-working former serviceman, was employed by the R. E. Gordon Furniture Company, a chair manufacturing operation which had opened at Woodfin in 1952, employing 150 men.[55] In 1962, Edward Phillips switched careers, and started working as a pipe fitter for Price Piping Company (a plumbing and heating company). 1962 was also the year that 297 Swannanoa Road became 110 Swannanoa River Road.[56]

The Phillips family story, as well as the story of their home on the Swannanoa River Road, must include the story of the adjacent Antique Tobacco Barn, a former tobacco warehouse. The large warehouse, which sits just west of the house, at the northeast corner of the intersection of Caledonia Road and the Swannanoa River Road (an original entrance to the Kenilworth), was originally built as “a cavalry barn and riding academy”[57], and later became a nightclub called the Plantation, before becoming a tobacco warehouse. In 1945, Fred Cockfield, of Lake City, SC, and Ray Haney, of Greeneville, TN, purchased the property and turned it into a tobacco warehouse, known as “Planters Tobacco Warehouse”. [58] At the time, “while bright tobacco was king in the piedmont and eastern regions of North Carolina, burley ruled in the western part of the state. At its peak, over 10,000 small farms, many less than an acre in size, produced burley tobacco in approximately twenty counties in the mountains and foothills. Half of that production occurred in Madison, Buncombe, Yancey, and Haywood counties. Burley provided an important economic supplement, its income often meaning the difference between solvency and bankruptcy for rural Appalachian families.[59] After harvesting, the tobacco was stored in huge warehouses, awaiting the annual tobacco auctions. As the Planters Warehouse opened for the 16th annual tobacco market season-1945, it was reported that the previous season, Western North Carolina had experienced record-breaking sales of burley tobacco, selling a total of 8,234,216 for a whopping $4,009,960.96.[60] Not surprisingly, it was reported that “buying was spirited”[61] at the Planters Warehouse on opening-day of the 1945 Asheville burley tobacco market. Following a 1947 fire, the Planters Warehouse was re-built and expanded considerably.[62]

The burley tobacco markets were highly regulated, with such Federal regulations governing the tobacco markets such as: “Each warehouse operator shall arrange his entire day’s sale in a continuous and orderly arrayed sequence of lots and rows of tobacco”, and in addition “Each warehouse operator shall designate to the Set Work Leader or Circuit Supervisor the starting point or lot for each day’s sale, and counting and grading will begin at this designated point and proceed to the closing point of the sale in an orderly sequence.”[63] This finely choreographed “orderly sequence” of displaying and selling required trained “handlers” who could properly set up and display the tobacco, in accordance with these stringent regulations. The Phillips family, living just next door to the hustle and bustle of the seasonal markets during the heyday of the burley tobacco markets, and following in the tradition of Asknish being used for boarding, they would provide room and board to the out-of-town “handlers” who would come to work the markets. Lockie Phillips would provide hearty meals for the hard-working men.

In 1999, James Ramsey, the then owner of the Tobacco warehouse, after 17 years of renting spaces to antique vendors as a sideline business, in between the seasonal waning tobacco markets, decided to transition totally from selling tobacco to selling antiques fulltime. Ransey opened his new business as the Antique Tobacco Barn. Now under new management, the Antique Tobacco Barn is still a popular and striving business. In 2007, following the death of Edward Phillips (2005), the new owners of the Antique Tobacco Barn purchased the former Asknish cottage. Since then, the house has been boarded up and subject to rapid deterioration.

The story of Asknish includes Western North Carolina’s early associations with the southern elites of Charleston and the low-country regions of South Carolina, and the post-antebellum explosive growth of Asheville in the late nineteenth-century boom following the arrival of the railroad, as well Asknish’s associations with the development of the Biltmore Estate and the Biltmore Forestry School. Asknish’s story also includes the history of burley tobacco production and sales, so important to Western North Carolina’s early and mid-twentieth-century economy. Attempts to find a suitable way to preserve and restore/rehab this picturesque and historically significant cottage have so far failed. Reminds me of the old adage- “Not to decide, is to decide not to!” –What a lovely shop it would make, just like the Biltmore Village shops established in the former cottages of the same size? Or what about tapping into Asheville’s tourism market, and opening the cottage as a short-term rental, or a unique small “boutique” hotel? Certainly, Asknish is worthy of preservation!

Photo Credits: (note: all photo captions by Dale Wayne Slusser)

Color photo of Asknish– by Dale Wayne Slusser https://www.gibbesmuseum.org/miniatures/collection/detail/E15F8AB5-CCFA-4246-8435-205830891062 and

Campbell Sisters Portraits– Miniature Portrait Collection at the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, SC. Available nnline at: https://www.gibbesmuseum.org/miniatures/collection/detail/E15F8AB5-CCFA-4246-8435-205830891062

Robert Blair Campbell, 1862– from post by Scott Morland originally shared this on 04 Nov 2015-granted with permission.

Asknish Crest-Plate VI, No. 13 from: The Heraldry of the Campbells, by G. Harvey Johnston. (Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston, Limited, 1921).

Azalea, c. 1900– Collection of Louisa Emmons, (a Cheesborough/Patton descendent), Morganton, NC.

Aerial photo of Asknish, Azalea and Bryant Antiques-NCDOT Aerial Photo #M-591, dated 03/08/1966, from a scan in the Dale Slusser collection.

Portrait- James Albert Tennent-from MJ Bumgardner, Ancestry.com

Pinecliff & Biltmore Gatehouse– Olmsted Archives, Flickr.com

1917 Sanborn Map closeup-Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1917-NCLive.org

Asknish Color Photos-by Dale Wayne Slusser

Asknish dining room Mantle– by Dale Wayne Slusser

Asknish second-floor stair rail– by Dale Wayne Slusser

“Forestry School at Asheville” Advert.– The Forester, Volume IV, (Washington, DC: The American Forest Association, June 1898) page 131.

Biltmore Forestry School students with Dr. Schenck– National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC ; [Digital Publisher: D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, UNC Asheville] Image: P2010.12.03 Contributor: Mrs. Ysabel Peabody of Letterman, California.

B & W photo of Asknish and drive-by Dale Wayne Slusser

“A. Reed & Sons” photo– Daniell, C. A., Abbott, F. D. (1895). Musical Instruments at the World’s Columbian Exposition: A Review of Musical Instruments, Publications and Musical Instrument Supplies of All Kinds, Exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago, May 1 to October 31, 1893, and the Awards Given for These Exhibits (from All Nations) with the Texts of the Same, Fully Revised. United States: Presto Company, page 284.

“Take Your Choice” C. Faulk advert.- Asheville Citizen Times, October 23, 1904, page 3.

Buying at Planters Warehouse– Asheville Citizen Times, December 4, 1945, page 9.

Asknish as viewed from the west of Swannanoa River Road-by Dale Wayne Slusser

[1] Duncan Donald McColl, Sketches of Old Marlboro. (Columbia, SC: Presses of the State Company, 1916) pp. 97-105.

[2] Jennie Merrill, “Some Campbells in South Carolina: Descendants of Rev. Hugh Campbell and his wife Susannah Campbell, daughter of Angus of Asknish.” – Journal of the Clan Campbell Society, Volume 20-22. (Virginia Beach, VA : Clan Campbell Society (United States of America), 1993), pp. 16-17.

[3] Henry Lee, The History of the Campbell Family. (New York, NY: R. L. Polk and Company, Inc., 1920), pp. 55-56.

[4] Agnes Morland Campbell, Echoes: A Biography of Robert Blair Campbell. (Greenwood, VA: Agnes Morland Campbell, 1930), pp. 28-34.

[5] From: http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=C000098

[6] “Massachusetts, State Census, 1865,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/MQCG-5GS : accessed 07 Dec 2013), Agnes Campbell in entry for Rachel Cushing, 1865.

[7] “United States Census, 1870,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/M8RV-3YH : accessed 07 Dec 2013), Agnes M Campbell in household of Elizur De Choiseul, South Carolina, United States; citing p. , family 9, NARA microfilm publication M593, FHL microfilm 000552997.

[8] “United States Census, 1880,” index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/M6S4-MSR : accessed 07 Dec 2013), C. M. Campbell, Dorchester, Colleton, South Carolina, United States; citing sheet 391C, family 0, NARA microfilm publication T9-1226.

[9] Caroline Morland Campbell is buried in Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston, SC.- http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=45005962

[10] Lucia purchased property on Turner Street in October of 1890 (the deed said she was a resident of New Orleans, LA)-see . “R. M. Johnson to Lucia B. Campbell” October 3, 1890 (Deed Book 73, page 441 in the records of the Buncombe Register of Deeds).

[11] “John & Edith Cheesborough, et. al. to Agnes M. Campbell” January 2, 1890 (Deed Book 77, page 81 in the records of the Buncombe Register of Deeds).

[12] Entries from the ledger books of W. H. Westall Co. , a building supply contractor in Asheville seem to link JA Tennent to the building of Asknish. Beginning in April 1891 there is an entry on page 417 of ledger book 1, for “J. A. Tennent- Biltmore, NC.” Following that are numerous entries up until September of 1891-all the entries after the first one is designated, “J. A. Tennent-Campbell”. As the first name was always the builder or purchaser and the second was the project, the Biltmore and Campbell entries indicate the same project. –Ledger Book 1, MS206.001A, North Carolina Collection, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

[13] Asheville Citizen, May 21, 1891, page 1.

[14]John Peyre Thomas, The History of the South Carolina Military Academy. (Columbia,SC: Walker, Evans & Cogswell Co., 1893) p. 269.

[15] Info from 2009 article by Catherine Bishir and Zoe Rhine in the online “North Carolina Architects and Builders: A Biographical Dictionary” http://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000220.

[16] Letter from Agnes Morland Campbell to Charles McNamee, dated September 25, 1897 from “1.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 17 Folder 71.

[17] Letter from Agnes Morland Campbell to Charles McNamee, dated January 5, no year, from “1.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 17 Folder 71.

[18] Letter from Lucia B. Campbell to Charles McNamee, dated only “Wednesday evening”, from “1.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 18 Folder 77.

[19] For the complete story of the Biltmore Forest School see: Carl Alwin Schenck, The Cradle of Forestry in America: The Biltmore Forest School, 1898-1913. (Durham, NC: The Forest History Society, 1998).

[20] “The Forester”, Volume 4, Issue 6, June1898. (Washington, DC: The American Forestry Association). p.131.

[21] Letter from Agnes Morland Campbell to Dr. Schenck, dated June 17, no year, from “2.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 6 Folder 39.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Letter from Agnes Morland Campbell to Dr. Schenck, dated August 25, 1902, written from “Mrs. Ridgely Penniman, “Elbemar”, Victoria Road, Asheville”, from “2.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 6 Folder 39.

[24] Carl Alwin Schenck, The Biltmore Immortals: Biographies of 50 American Boys Graduating from the Biltmore Forest School which was the First School of American Forestry on American Soil. Darmstadt, Germany: L.C. Wittich, 1953.

[25] Letter from Agnes Morland Campbell to Charles McNamee, undated from “1.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 17 Folder 71.

[26] Letter from Agnes Morland Campbell to Charles McNamee, dated March 27, 1894 from “1.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 17 Folder 71. and another Letter from Agnes Morland Campbell to Charles McNamee, dated April 3, 1897 from “1.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 17 Folder 71.

[27] Letter from Agnes Morland Campbell to Charles McNamee, dated January 30, 1897 from “1.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 17 Folder 71.

[28] Letter from Agnes Morland Campbell to George Weston, dated September 25, 1897 from “2.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 6 Folder 39.

[29] Letter from Lucia Blair Campbell to Dr. Schenck, dated November 8th, no year, written from “Asknish”. from “2.1/1 Biltmore Estate Superintendent’s Office, Incoming Correspondence”, Box 6 Folder 41.

[30] See- “Port Richmond Branch Library, The First 50 Years: 1905-1955”, by Andrew Wilson. March 26, 2009 at http://www.nypl.org/blog/2009/03/26/port-richmond-branch-library-first-50-years-1905-1955.

[31] 08/20/1901 Agnes M. Campbell to Mary H Granger [D/T] Db. 52/431. “Know by All men of these Presents, That I, Agnes Morland Campbell of Asknish Biltmore near Asheville…in consideration of Two Thousand dollars to me paid by Mary Hoyt Granger, of Zanesville…”.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[32] “George Wright, Comm. to Moses & Mary Hoyt Granger” September 12, 1906 (Deed Book 147, page 429 in the records of the Buncombe Register of Deeds.

[33] “Moses & Mary Hoyt Granger to James Stikeleather & Brewster Chapman” November 16, 1911 (Deed Book 145, page 190 in the records of the Buncombe Register of Deeds).

[34] “C. Brewster Chapman to Alice E. Reed” May 29, 1911 (Deed Book 176, page 187 in the records of the Buncombe Register of Deeds).

[35] “A. L. Reed”, Asheville Gazette News, February 5, 1908.-from Biography file at the Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library Asheville, NC.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] “Death of M. O. Brown- He Was 62 Years of Age and A Native of New Jersey”, Asheville Citizen-Times, December 23, 1899, page 1.

[39] “Melvin Brown Dead-End Came Monday After An Illness of Several Weeks”, Asheville Register, August 24, 1901, page 1.

[40] 11/25/1913 A. L. & Alice Reed to R. A. Wilson & E. G. Hester 1 ACRE KENILWORTH Db. 187p. 331. “northern section of Db. 176 p. 187”.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[41] 04/20/1917 L. F. & Susie Mathews to Alice E. Reed SWANNANOA DRIVE BK 154 PG 54 (This is 1 acre meadow to the west of the original lot-now parking for Tobacco Barn Antiques)-Buncombe County of Deeds.

[42] Asheville Gazette-News, November 4, 1911, page 8.

[43] “Last Rites For Mrs. Reed Held”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 10, 1922, page 3.

[44] “Reed-Davis Marriage Announced Yesterday”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 23, 1923, page 6.

[45] 02/25/1924 A. L. Reed & Fay Reed AGREEMENT Db. 279/315.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds

[46] “HUSBAND SLEPT IN BASEMENT IS WOMEN’S CHARGE-Mrs. Alanson L. Reed Asks Alimony Here From Millionaire”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 12, 1926, page 1.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] 11/05/1936 Flora L. Reed to JH & Alice Reed Hughes BUN CO Db, 492/158. [reference Db. 453/546]- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[50] 08/12/1937 Alice Reed Hughes to E.C. & Ellis Frady; Grace Frady Pennell Db 500 p 247.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[51] North Carolina, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998-Buncombe Wills, Book G-J, 1909-1921, page 408. Ancestry.com

[52] “Miss Mae Frady”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 24, 1945 – Page 2

[53] 04/17/1946- E. C. & Elsie Frady to Joseph William Parker, Db 608 p 267- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[54] 04/22/1952- Joseph William Parker to Edward L. & Lockie Phillips-Db 718 p. 392. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.-

[55] Asheville Citizen Times, December 17, 1952, page 16.

[56] See: Hill’s Asheville (Buncombe County, N.C.) City Directory [1962]

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill- https://lib.digitalnc.org/record/24917

[57] Asheville Citizen Times, February 10, 1947, page 1.

[58] Asheville Citizen Times, February 10, 1947, page 1.

[59] “Burley Tobacco”- https://digitalheritage.org/2010/08/burley-tobacco/ -Copyright, Western Carolina University.

[60] Asheville Citizen Times, November 18, 1945, page 16.

[61] Asheville Citizen Times, December 4, 1945, page 9.

[62] Ibid.

[63] “7 CFR § 29.75a – Display of burley tobacco on auction warehouse floors in designated markets.”- LII Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (e-CFR) Title 7 – Agriculture Subtitle B – Regulations of the Department of Agriculture CHAPTER I – AGRICULTURAL MARKETING SERVICE (STANDARDS, INSPECTIONS, MARKETING PRACTICES), DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE SUBCHAPTER A – COMMODITY STANDARDS AND CONTAINER REQUIREMENTS PART 29 – TOBACCO INSPECTION Subpart B – Requirements mandatory inspection § 29.75a Display of burley tobacco on auction warehouse floors in designated markets. Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute- https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/7/29.75a