by Dale Wayne Slusser – December 2024

“More than 1,000,000 new spindles were added to the Southern textile mills in 1924 and 1925. While Eastern and Northern capitalists continue to purchase established plants and erect new mills, Southern capital is being employed for building new mills and expanding established ones in increasing volume,” reported the October 1926 issue of Manufacturers Record.[1] One of those new mills that was then being erected was Beacon Manufacturing’s new plant at Swannanoa, NC, twelve miles east of Asheville, NC.

In 1904, Charles D. Owen and his son, Charles D. Owen, Jr., along with a cousin, bought the defunct Beacon Manufacturing Company in New Bedford, Massachusetts (executive offices in Providence, R. I.). The company made cotton flannel bed blankets and bath robes, and later added infant blankets to their product line. In 1915, at the death Charles D. Owen, the company had almost 1,000 employees, and by 1919, the company had over 1,600 employees.[2] But facing increasing union pressure at the plant in New Bedford, and in an effort to cut his labor costs, Charles D. Owen, Jr., like many other Northern textile mill owners, decided to look southward. And to that end, in 1924 Owen purchased several hundred acres, adjacent to the town of Swannanoa, NC on which to build a new textile plant.[3] “Ground was Broken”[4] on July 12, 1924, commencing construction of Beacon’s new Swannanoa facility.

Architect/Engineer, Knight C. Richmond, of Providence, Rhode Island, who had designed the original New Bedford plant, was hired to design the new plant at Swannanoa. Knight Cheney Richmond, came from a textile owners’ family. Richmond’s grandfather, George M. Richmond, in 1866, just before his death, had obtained controlling ownership of Crompton Mills near Providence, RI. The Richmond family would subsequently dominate the company for many years. Knight Richmond’s uncle, Frank Richmond was appointed the president of the company in 1866, and another uncle, Howard Richmond was hired as the treasurer.[5] Knight Richmond was two years old when his family took over Crompton Mills, so not surprisingly, after working for his family’s mill for a few years, as a young man, Knight enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, graduating in 1890 with a B. S. in Mechanical Engineering.[6]

Although not germane to our story, after graduating from MIT, Knight Richmond “entered the office of Nier, Hartford, and Mitchell in Chattanooga, Tenn., as a draftsman. The following year he became treasurer of the P. A. Demens Woodworking Co. at Asheville, N.C., where he remained for two years”.[7] However, the company went into receivership in 1892. Knight Richmond and his future father-in-law James Monroe Campbell were two of the three claimants who received favorable judgements in the receivership against the P. A. Demens Woodworking Company- Richmond for $600 and Campbell for $11,000.[8] Knight Richmond immediately moved back to Providence, RI. However, he briefly returned in January 1896 to marry his bride, Miss Phebe Ann Campbell. The couple was married at “Oakdale”, the Campbell family home in “Victoria” (now the St. Dunstan’s Circle area in Asheville). Also, Knight & Phebe Richmond’s names, along with her parents’, are on the deed of a property transfer to Eugene Sawyer in 1898. Eugene Sawyer was buying the “J. M. Campbell Building” at 18 Church Street in downtown Asheville. Campbell had built the building in 1895.

By 1924, Knight Cheney Richmond, had become a noted “Mill Architect and Engineer”[9] (as he advertised himself in 1904), based in Providence, RI. He specialized in “slow-burning construction”, which used heavy timber and masonry as fire-resistant materials, especially suitable for textile mill construction. Heavy timber posts with thick timber flooring were used instead of light-weight framing lumber (studs and joists). Even today in our modern building codes, heavy timber construction has a higher fire-resistance rating than steel construction, as the heavy timber quickly chars and slows down the burning of the timber, whereas a steel member will melt or “fail” long before a heavy timber member will fail. Also, Richmond designed his factory buildings to be built of “a saw-tooth type construction”[10], meaning that they were constructed with each section of the factory having a clerestory roof, sloped up to the north, allowing natural northern light and ventilation to penetrate the interior of the factory.

In conjunction with the building of the new factory at Swannanoa, Beacon Manufacturing also decided to build an accompanying “mill village” to house his workers (then called “operatives”), several of which initially moved down from New Bedford. Beacon Manufacturing hired the premier “mill village” designer, landscape architect, E. S. Draper to design the new village. This included the design and layout of the streets, lots, and utilities.

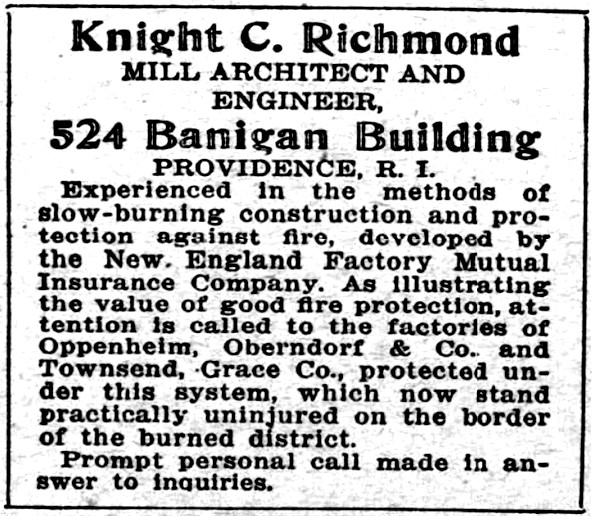

Earle Sumner Draper, had a similar background to architect Knight Richmond- he was born and educated in Massachusetts, and he came from a prominent textile mill owning family. Earle S. Draper was born in Falmouth, MA on October 19, 1893 to photographer Frederick Ward Draper and his wife Bertha Sumner Draper.[11] Thomas Draper (Earle’s great grandfather) and his brother James began manufacturing knit goods in 1851, in the old Withington house at the corner of Pleasant Street and Washington Street in Canton, Massachusetts. Thomas Draper died on May 29, 1856 and his son Charles Draper (Earle’s grandfather) took his place. Meanwhile, James Draper, Thomas Draper’s brother and business partner-at first having decided to move back to England following Thomas’ death, but convinced by his family to stay-Draper decided to form his own textile mill business utilizing a knitting machine that he had constructed for himself. In 1861, James Draper took on George F. Sumner as a partner and the firm was called Draper and Sumner. In 1865, they purchased the Morse Machine Works in South Canton, and in 1869 bought the failed Canton Woolen Mills, which had been operated by his nephew Charles (Earle’s grandfather). After James Draper died in 1873, his sons took over the business. They dissolved the partnership with George Sumner and in 1875 renamed the business Draper Brothers, which in 1889 was incorporated under the name of Draper Brothers Company.[12] Interestingly, Earle Sumner Draper received his middle name from his mother’s maiden name, not from his great-uncle’s business partner George F. Sumner. Both the Draper and Sumner families were prominent and prolific families in Massachusetts since the eighteenth-century. Earle S. Draper’s grandfather and great-great uncles’ company, the Draper Brothers, founded in the 1870’s is still in business (2024) as the Draper Knitting Company, and is run by the 6th generation of the Draper family, with Kristin Draper as its President, Marketing & Development Manager.

E. S. Draper graduated with a B.S. in landscape architecture from the Massachusetts Agricultural College, (now the University of Massachusetts at Amherst) in 1915.[13] After college, he was hired by John Nolen, the premier city planner of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Nolen sent him south to Charlotte, North Carolina, to be the firm’s representative for its southern projects: Myers Park subdivision, in Charlotte and the town planning of the new town of Kingsport, Tennessee. In 1917, Draper, who had settled in Myers Park (where he built a family home) established his own firm in Charlotte, specializing in upper-class residential neighborhoods and mill villages.[14]

“The landscape architecture is the least appreciated and understood of professions”[15], stated E. S. Draper, during his speech as the guest speaker at a conference of the American Society of Landscape Architects (which then only had 145 members) in New York City, in January of 1924. Draper went on to report that, “landscape architecture in his home state had brought about the greatest evolution in the social life of the working man there in the last decade.”[16] Elaborating further, “The speaker described improvements made through his plans upon the homes of employees of 150 textile mills throughout the south, by which more than 75,000 working persons had benefited. Many of the workers, he [Draper] said, came from the mountains where they were accustomed to almost inconceivable living conditions.”[17]

In his article titled “Southern Textile Village Planning” in the October 1927 edition of Landscape Architecture magazine, E. S. Draper gives us a glimpse into his design principles and methodology for designing and building an ideal “mill village”. Draper prefaces his remarks by saying that, “…there are 1,200 textiles mills in the South at the present time, employing several hundred thousand workers.”[18] In general, the requirements for planning a “new southern textile village”, says Draper, “are practically the same as any lotting or subdivision development”, such as designing the topography of streets and lots to handle adequate drainage and circulation. Specific to the planning of a textile village, Draper notes is that: “It is quite important that the streets and pathways be laid out to give direct and adequate circulation to and from the mill village center, and to the adjoining town and center.”[19] One of the reasons for the importance of locating the village close to the mill, says Draper, is that “practically all the workers return to their homes for the noonday meal, and the majority of them walk.”[20] As far as providing easy access from the mill village to the adjoining town, in the case of the Beacon plant, this was easy to accomplish as “downtown” Swannanoa was literally adjacent to the mill village, and already had established shops and train station. Draper also advocates for the village to have their own community center housing a general store and a second floor “lodge hall” (meeting room), and their own churches of the various denominations. Draper also advocates for concrete sidewalks with a planting strip between it and the street, “because of the amount of walking done in the village, and the advisability of keeping dirt out of the mill”.[21] However, he did not utilize either in the Beacon village.

In his article on textile mill village planning, Draper also discusses lot sizes. He says that the “average bungalow lots in southern textile villages are from 65-to 75-ft. frontage and 125 to 175 feet deep,-150 feet being the average depth.”[22] Two determining factors for the lot sizes, says Draper, are first that the insurance premiums are higher if the houses are less than thirty feet apart, and second that “the operatives themselves are not used to living close together and want a certain amount of yard space.”[23] Analyzing the lots that Draper designed for Beacon Village, we see that they generally have a frontage of between 55-to 65 ft and a depth variation between 115-to 200 ft. Of course, the narrower frontage is due to the fact that Draper in his article had used 35 ft as the house width, but as in Beacon Village, the narrower the house, the smaller the frontage can be.

Although Beacon’s mill village was designed for ease in walking to and from the mill, it was also designed for automobiles, not only with its paved streets but also providing garages for each house. In most of the houses, double garages were built between every other house, providing a driveway and garage on each side for the adjoining houses. In a few cases, due to lot constraints, group garages were provided nearby.

By the time construction began on the Beacon factory at Swannanoa, a contract had already been let to the Jackson-Campbell Company of Asheville to design and build fifty houses[24], as the start of the new mill village. Jackson-Campbell Company, renamed from the Grove Park Construction Company, was established in 1924 by business partners, Linwood B. Jackson and W. R. Campbell (apparently, no relation to the J. M. Campbell mentioned earlier). Both men were also active in other businesses- L. B. Jackson (then only 27 years old) was at the time building his modern office skyscraper in downtown Asheville, and W. R. Campbell was the sales manager for E. W. Grove Investments. Incidentally, W. R. Campbell was the “buyers’ agent” for Beacon Manufacturing when they acquired the Swannanoa property. By October 1924, just three months after the factory ground-breaking ceremony, a photo appeared in the Asheville Citizen-Times showing the first ten houses of the Beacon Village already having been erected, along Edwards Avenue.[25]

Apparently, E. S. Draper did not design the houses in his planned mill villages, however he did provide general guidelines as to their style and sizes. In his 1927 article, he addresses the design of “the typical mill village bungalow”.[26] Draper writes: “The bungalow or cottage type of house is most suitable, not only from a climatic standpoint, in that the rooms on the ground floor are cooler, but because of the fact that the village people on account of having lived in mountain or rural cottages, have never been accustomed to climbing stairs, and will not do so when it can be avoided”.[27] Draper also further describes the typical size and layout of the typical mill house: “This normally includes hallway, kitchen, dining room or dining alcove, living room, bathroom, and several bedrooms in the six-room house. In the four-room house the hallway may or may not be included and the dining room is usually a living room as well”.[28] Although today we describe house sizes either by their area (square footage) or by the number of bedrooms and bathrooms or both-i.e. “a three-bedroom, 2 bath, 1,800 sf…”, but in the late-nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century, houses were simply described by the number of overall rooms (which usually did not include bathrooms or closets).

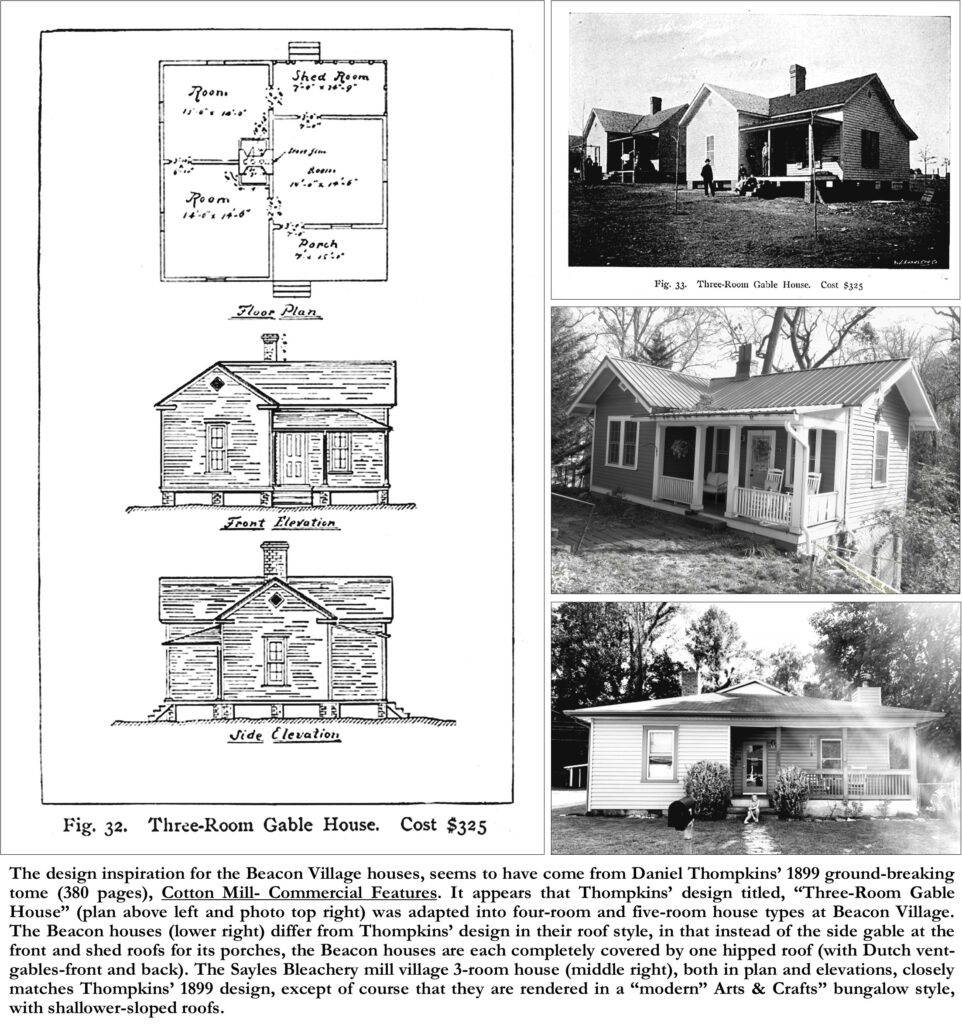

Draper’s description, as well as the design of the “typical mill village house”, and for that matter Draper’s design concepts for the layout of the typical mill village, all were building on the pioneering work of Daniel Thompkins (also of Charlotte, NC). In his 1899, ground-breaking tome (380 pages), Cotton Mill- Commercial Features, Thompkins presented many progressive improvements for designing and building modern textile mills, mill villages, and mill houses (which he calls, “operatives’ homes”)[29]. “It was formerly the custom to build for operatives long rows of houses exactly alike, and in most cases adjoining one another. But it has transpired that this is not the best plan”, advocated Thompkins, as “Different families have different tastes, and as operatives grow in intelligence and prosperity, this differentiation in taste becomes more marked”.[30] Thompkins went on to provide engravings of designs which he recommended for various sizes of mill houses. Interestingly, the mill houses built at Beacon Village (twenty-five years after Thompkins publication), closely resemble, especially in plan, Thompkins’ design titled, “Three-Room Gable House”.[31] At Beacon Village, Thompkins’ three-room design was adapted into four-room and five-room house types. For the four-room house type at Beacon Village, another room was added behind the living room, giving the house a living room, eat-in kitchen, and two bedrooms. Of course, all the Beacon Village houses had the added convenience of a modern indoor bathroom with running water and sewer services. The five-room house which was built at Beacon Village also followed Thompkins’ design, with the addition of a third room on the gabled side of the house, giving the house a living room, eat-in kitchen, and three bedrooms. The Beacon houses differ from Thompkins’ design in their roof style, in that instead of the side gable at the front and shed roofs for its porches, the Beacon houses are each completely covered by one hipped roof (with Dutch vent-gables , front and back). Just an interesting note- at the Draper-designed Sayles Bleachery mill village, then being built in nearby Asheville, the “3-room” (living room, eat-in kitchen, and one bedroom) mill house looks very similar, both in plan and elevations, to Thompkins’ 1899 design for a “Three-Room Gable House”, except of course that they are rendered in a “modern” Arts & Crafts” bungalow style, with shallower-sloped roofs.

A unique feature of the Beacon Mill Village houses, was their interior finish, as all the walls and ceilings were finished out with horizontal beaded boards. Interiors finished with wood boards instead of plaster was prevalent in Western North Carolina during the nineteenth and early twentieth century, especially in rural areas. The main reason for this was the lack of skilled plasterers and the lack of money for a homeowner to hire them. Conversely, there was both an abundance of wood and of local sawmills dotting the country. Of course, the other advantage to wood walls was that they could be installed by unskilled workers or homeowners. In the case of the houses at Beacon Village, I suspect the use of wood walls was used as a cost-savings measure over hiring plasterers, and perhaps also as a time-saving measure. The initial building of the first houses, as well as the subsequent building of the mill houses were always connected with an accompanying addition to the mill, which coincided with the hiring of more workers requiring more housing.

The start of the Beacon Manufacturing plant at Swannanoa and its accompanying mill village, was followed four years later, in 1928, by another company building boom. Beacon Manufacturing announced that it was going to literally double the size of their Swannanoa plant, and at the same time double the size of the mill village to accommodate the new workers it would be hiring. No doubt the expansion at the Swannanoa plant was prompted by increasing labor troubles at the New Bedford plant in Massachusetts. Less than a month after Beacon’s announcement, a massive strike began in New Bedford. The New Bedford Cotton Manufacturers’ Association, representing mill owners from twenty-six textile mills in and around New Bedford, announced that it planned to cut wages by 10% to keep in competition with southern mills. Over 30,000 laborers in New Bedford, initially represented by the New Bedford Textile Council (the union of skilled workers), stopped working on April 16th, 1928. The strike not only became contentious, fueled by communist-party representatives, but it lasted for six months, finally ending after the union members accepted a 5% pay cut in October 1918. Fortunately, the Beacon Manufacturing Company was able to avoid being involved in the massive strike. Remarkably, and adroitly, the owners of the Beacon Manufacturing Company, just before the April 16th strike was called, were able to convince their employees to withdraw from the New Bedford Textile Council (the union). Beacon Mill further announced that they would be “conducted as an open shop”, with “its operatives accepting the ten percent wage reduction”.[32]

The 1928 expansion of the Beacon Mill village at Swannanoa included the addition of fifty more houses- four room houses, five-room houses and six-room houses.[33] The new expansion was designed again by architect/engineer Knight Richmond. It is unclear who designed the houses; however, it is most likely that they were built from the 1924 plans and built on the remaining vacant lots laid out by E. S. Draper in 1924.

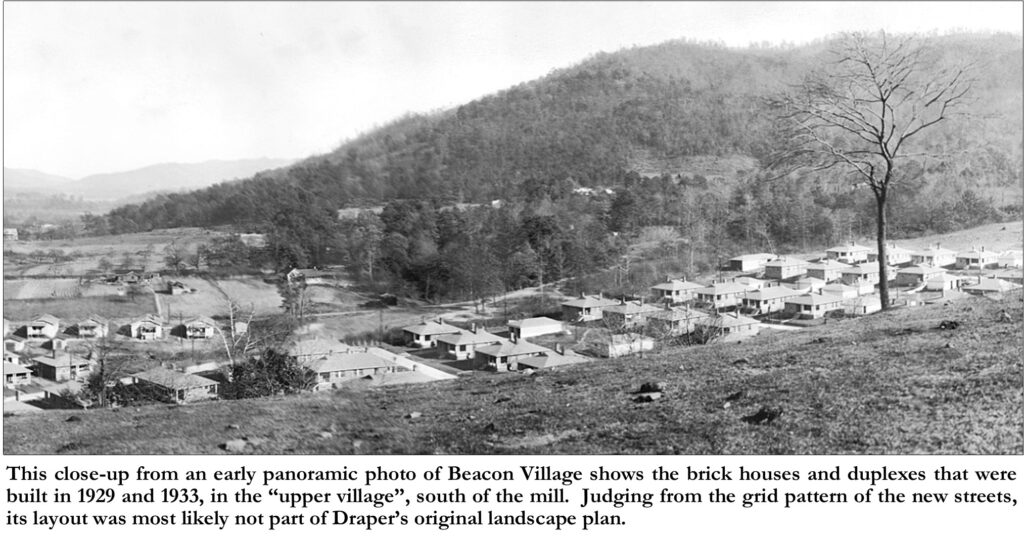

Just a few months later, in the Spring of 1929, Beacon Manufacturing announced yet another wave of expansion to the mill and the village. The village expansion included the addition of 42 new homes, all to be built “south of the mill”, which was on land behind the mill and across the railroad line. The new section of the village was later referred to as the “upper village”. Judging from the grid pattern of the new streets, its layout was most likely not part of Draper’s original landscape plan. The 42 “houses” included 10 four-room houses, 10 five-room houses, and 20 duplexes.[34] The 20 single-family houses followed the same established floor plans, however, instead of being clad in wood siding, they were clad in a veneer of brick. The duplexes, also to be clad in brick veneer, were a new type of house for Beacon village. Each duplex housed two families, separated by a center wall. Topped by a single hipped roof, at first glance each duplex appears to be a single bungalow. Each side of the duplex consisted of a front porch, and three consecutive “shot-gun” style rooms: living room, bedroom, and kitchen (with an adjoining bath). Each side was a three-room house, suitable only for singles, newlyweds, or childless couples! The construction of the 42 houses was contracted out to the Black Mountain Lumber Company.

The 1929 mill and village expansion at Beacon’s Swannanoa plant was just finishing when the “Great Crash” hit in October of 1929. However, it did not affect Beacon’s expansion, as in December of 1929, the company announced that in addition to erecting two new warehouses, it was also going to “construct a concrete highway between the two mill villages at Swannanoa”.[35] All this new work was in preparation for the hiring of 100 new workers, to be hired January 1, 1930.

The final project of the 1929 expansion at Beacon Village was construction of the James H. Nolan Baseball Park. The opening day at the new employee baseball park, named after Beacon’s auditor and baseball enthusiast, James Nolan, was on April 5, 1930. The new field was built south of the mill on the east side of Dennis Street in the upper village. The location is now the site of a new residential street named Nolan Field Lane.

As the Great Depression set in, the Beacon Mill at Swannanoa continued production, providing work for its 320 employees. However, Beacon Manufacturing’s plant in New Bedford, MA was struggling to survive, resulting in its closing in April 1933. Beacon Mill owners C. D. Owen, Sr. and his son C. D. Owen, Jr. announced that although they were not abandoning the New Bedford plant, as it was only “temporarily closed”,[36] they would have the machinery from the New England plant shipped down and installed at the Swannanoa plant.[37] No expansion of the plant was anticipated as the machinery was to be installed in the “considerable unused floor space in the buildings at Swannanoa”.[38] However, in the end, a 70,000 s.f. one-story addition to the factory was constructed in 1933 to house the new machinery.

Although Beacon Manufacturing promised that no supervisors or superintendents would be hired or brought down from the New Bedford plant, the increased machinery did require increased employment. To meet the increase in workers, Beacon Manufacturing decided to build 15 new 4-room and 5-room brick houses in 1933. Black Mountain Lumber Company again was hired as the contractor for the new houses. Also in 1933, Beacon Manufacturing announced a wage increase for its 450 employees and that with the additional machinery and the initiation of two 40-hour shifts it would soon be hiring 300 more employees.[39] “Beacon Blankets” continued to be produced during the Great Depression years. In fact by 1936, Beacon Manufacturing had 1,600 employees, boasting the “the biggest payroll in the history of the Swannanoa plant”.[40] In 1937, Beacon Manufacturing purchased the Oconee Mills in Westminster, SC. The company used Oconee Mills to produce yarn to be used for the blanket making operations at Swannanoa.[41]

The 1940’s brought with it new challenges, yet new benefits for Beacon Manufacturing and its employees and mill village. In the early 1940’s the Beacon plant and mill village gained easier access to its facilities when the old Black Mountain Highway (U.S. 70-now “Old U. S. 70”) was rerouted from just west of Swannanoa to Black Mountain. The new route, which eliminated two bridges across the Swannanoa, was constructed in a straight line between the Swannanoa River to the north and the Beacon plant and village to the south.[42] Also, in 1940 a new eight-inch public water line was installed to supply the two hundred houses in the mill village. The new line supplemented Beacon Manufacturing’s existing private six-inch line.[43]

In November of 1941, just a month before the United States would officially enter the war, Beacon Manufacturing was awarded a contract by the War Department for “$163,569 worth of cotton blankets to be manufactured at Swannanoa”.[44] As the war progressed, numbers of Beacon Manufacturing employees (men and women) were called into service. The familial-like bond of Beacon Manufacturing with its employees manifested itself during these times, as not only did the employees actively participate in buying war bonds and helping with the Red Cross Relief efforts, but also, they continued to care for those serving. When a small group of the employees came up with the idea, in December of 1942, to send a Christmas gift to each of 360 former fellow Beacon employees who were in active service, “the idea spread so swiftly” throughout the plant that within two days the employees had raised $1,900 towards the effort. When Charles D. Owen, heard of the employees’ plan, he decided that in addition to the gift boxes, that the company would also send a check for a “substantial amount of money” to each individual serviceman as well.[45] This practice was carried through the war years. Both ensuing Christmases, 1943 and 1944, Beacon Manufacturing reported having over 600 employees serving in the Armed Services, all who would be receiving checks and gift boxes.[46]

With the end of the war in 1945, returning veterans were encouraged and aided by the U. S. Government in transitioning back into civilian life. In fact, consumerism, such as the buying of houses and cars and furniture were encouraged as an economic stimulus to renewing America’s “prosperity”. Federal programs were developed, such as Federal Housing Administration (FHA) loans and the GI Bill, giving many returning veterans the desire and ability to buy a home. This post-war promotion of individual home ownership, combined with the pre-war decline of “welfare capitalism” would greatly affect the future of Beacon Village. One of the many programs initiated in the “first hundred days” of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first term of office, was the “Cotton Textile Code”. The code was obviously enacted by anti-company-town proponents. The new code advocated for the abolishment of company-sponsored housing, with shameless and blunt statements in the code such as: “There is something feudal and repugnant to American principles in the practice of employer ownership of employee homes”.[47] The code suggested replacing the employees’ housing benefit with an increased wage. Stopping short of prohibiting and outlawing company towns, the code required the companies “to consider the question of plans for eventual employee ownership of homes in mill villages”.[48]

“Following a trend in industries throughout the nation”, reported the Asheville Times on October 14, 1948, “the Beacon manufacturing company is selling 231 dwelling units in the company’s mill village in Swannanoa to its employees”.[49] The current employee occupants of each house purchased their house from Beacon for an average price of $300 per room (excepting kitchens, pantries, and bathrooms) for the older houses, and $400 to $600 for the newer homes.[50] In the end, Beacon sold 162 dwellings to its employees. Some of the houses did not have adequate separation or yard space to be used as private homes. I suspect some of the unsellable dwellings were those which had been built directly in front of the mill with little yard space. The negotiations and deeds for all 162 dwellings were drawn up separately, although all deeds were registered on the same day, November 23, 1948.[51] The Beacon Manufacturing Company was one of the first textile companies in the area to sell off its mill village houses. The Sayles Bleachery village houses in nearby Asheville were not sold off to employees until 1962. The Champion Paper Mill village at Canton, NC, west of Asheville, did not sell off their mill houses to its employees until the company was sold in 1999. Enka Park, the mill village of the Dutch-owned company, ENKA in Candler, NC west of Asheville, was not sold off until 2001 when Enka’s successor BASF sold the village to Biltmore Farms, to be incorporated into the new Biltmore Lake residential development.

The Owen family sold out its interest in Beacon Manufacturing to National Distillers in 1969, and the company was later sold to Cannon Mills and eventually Fieldcrest Cannon. In 2001, Beacon Blankets, then owned by Pillowtex, was sold to an investment group made up of current and former employees and an Asheville investor. Unfortunately for Beacon Blankets and its remaining three hundred employees, just a year later, in 2002, the company shut down the Beacon Mill and moved its production to its plant in Westminster, SC. Then in 2003, the huge, abandoned mill caught fire and was destroyed.

The adjacent former mill village houses survived the 2002 mill fire and continued to be bought and sold. But exactly one hundred years after the first houses were built in 1924, a record-breaking catastrophic flood in September 2024, caused by hurricane “Helene”, almost destroyed the entire “lower village”. The flood waters completely submerged some of the houses up to their roofs. The aftermath was that some of those houses had to be condemned immediately after the flood, but even the affected houses that were not condemned, had to be emptied out and stripped back to their framing and left to dry out. Tons of polluted mud and sludge inside the houses had to be cleared out. Some property owners have accepted low offer buyouts for their properties-but those houses will most likely be demolished. However, the fate of the remaining historic houses is still in dire jeopardy, as many of the homeowners did not have flood insurance (the village was not in the 100-year flood plain), and/or have not received enough FEMA or insurance funds to rebuild. The Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County have aided in the rebuilding of Beacon Village through its post-flood “Hurricane Helene Recovery Grant Program”, which was established specifically to help owners of damaged historic structures rebuild.

Photo Credits:

Beacon Blankets Logo– America’s Textile Reporter: For the Combined Textile Industries, Volume 34 No. 40, September 30, 1920, pg. (27) 3431.

P. A. Demens Wood Working Co. Advertisement–Asheville Citizen-Times, January 6, 1891 ·Page 4.

Knight C. Richmond— Advertisement in the Baltimore Sun, Baltimore, MD, February 1, 1904, pg. 8.

Draper Brothers Sketch– Draper Brothers Company, C/O Post Box 701 Cataumet, MA 02534 –https://www.facebook.com/DraperKnittingCompany/photos

Earle Sumner Draper– Pioneers of American Landscape Design II: An Annotated Biography, Edited by Charles A. Birnbaum and Julie K. Fix. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Cultural Resources, Heritage Preservation Services, Historic Landscape Initiative, 1995), pg. 45.

Beacon Old Village Plat– 11/11/1948 Beacon Manufacturing Co, PLAT OLD VILLAGE Db. 24 p. 18. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Early View of Beacon Village House– Asheville Citizen-Times, Oct 12, 1924 ·Page 18.

Three-Room Gable House plan– Cotton Mill- Commercial Features, by Daniel A. Thompson. (Published by the author: Charlotte, N.C., 1899) Figure 32.

Three-Room Gable House photo– Cotton Mill- Commercial Features, by Daniel A. Thompson. (Published by the author: Charlotte, N.C., 1899) Figure 33.

Sayles Village Three-room House– photo by Dale Wayne Slusser-2024.

Typical Beacon Village House– courtesy of Elizabeth Barker, Beacon Village, Swannanoa NC.

Photo of Early Phases of Beacon Village– Image Ball2035-Beacon Manufacturing Company, Swannanoa, c. 1920’s- E. M. Ball Photograph Collection, University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections and University Archives, Asheville, NC.

First Baseball Game at Nolan Field– Image O180-DS –Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC

Close-up of brick houses & Duplexes-Close-up of right side (southeast) of Beacon Mill and Village Complex- Image O248-DS -Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

Christmas Advert. -Beacon Manufacturing– Asheville Citizen-Times, December 25, 1942, pg.17.

Beacon Sells Houses– The Asheville Times, October 14, 1948, pg. 12.

Beacon Village Underwater– courtesy –Catherine Voorhees Wood-homeowner of a Beacon Village home that was flooded during hurricane Helene in September 2024.

[1] “Southern Mills Add More Than 1,000,000 Spindles in Two Years”, by Carroll E. Williams, Manufacturers Record, Volume 90, Issue 2, October 28, 1926 (Baltimore, MD: Conway Publications, 1926) pg. 91.

[2] Info from: “Beacon Blankets: The heart of a community.” by Jonathan Austin, Smoky Mountain Living Magazine, posted February 1, 2022, 12:00 AM. https://www.smliv.com/stories/beacon-blankets/

[3] “Plant to Manufacture Blankets to Be Erected Immediately by Northern Concern At Swannanoa”, Asheville Citizen-Times, April 20, 1924, pg. 1.

[4] “WORK STARTED ON MILLION DOLLAR TEXTILE PLANT”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 13, 1924, pg. 1.

[5] American Textile/Clothing Manufacturers: Crompton Mill/Crompton-Richmond Company, https://histclo.com/fashion/store/man/alpha/c/man-cromp.html

[6] Catalogue of the Alpha Delta Phi Society, Alpha Delta Phi Executive Council of the Alpha Delta Phi Fraternity, 1899, pg. 222

[7] American Society of Mechanical Engineers Transactions 1930: Vol 52, pg.86.

[8] “Receiver Appointed”, Asheville Weekly Citizen, March 24, 1892, pg. 2.

[9] Advertisement in the Baltimore Sun, Baltimore, MD, February 1, 1904, pg. 8.

[10] “Plant to Manufacture Blankets to Be Erected Immediately by Northern Concern At Swannanoa”, Asheville Citizen-Times, April 20, 1924, pg. 1.

[11] See Ancestry.com for genealogical information for the Draper and Sumner families.

[12] From: Canton Comes Of Age- 1797 – 1997: A History Of The Town Of Canton, Massachusetts, Chapter Two- Canton’s Commerce. https://www.canton.org/canton/Canton%20Mass_%20Historical%20Society,%20Canton%20Bicentennial%20Book,%20Chapter%202.htm

[13] “Degrees Conferred-1915”, Massachusetts Agricultural College Bulletin, Volume VIII, No. 1, January 1916, Amherst, Massachusetts, pg. 151.

[14] From: Biographical Note:, Earle Sumner Draper, Sr. Papers, #2745. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

[15] “LANSCAPE ARCHITECTS ARE TOLD OF SOUTH”, The Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, NC, January 22. 194, pg. 20.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Southern Textile Village Planning”, Landscape Architecture, Vol. XVIII, No. 1, October 1927. (Boston, MA: Landscape Architecture Publishing Co, 1927), pg. 1

[19] “Southern Textile Village Planning”, pg. 5.

[20] Ibid.

[21] “Southern Textile Village Planning”, pg. 6.

[22] “Southern Textile Village Planning”, pg. 13.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Textile World, March 6, 1926 (New York, N.Y.: Bragdon, Lord & Nagle Co., 1921), pg. 71 (1665).

[25] “BEACON MILL VILLAGE”, photo with the following caption below: Many attractive homes are being erected in the Swannanoa section for use of employees of the new Beacon Mills.”, The Sunday Citizen, Asheville, NC, October 12, 1924, pg. 19.

[26] “Southern Textile Village Planning”, pg. 10.

[27] “Southern Textile Village Planning”, pg. 10-11.

[28] “Southern Textile Village Planning”, pg. 10.

[29] Cotton Mill, Commercial Features, D. Augustus Thompkins (Published by the author: Charlotte, N.C., 1899) pg. 114.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Cotton Mill, Commercial Features, “Figure 32 Three-Room Gable House”, plan on pg. 115, and photo on pg. 116.

[32] “TEXTILE WORKERS STRIKE ON MONDAY”, The Plain Speaker, Hazelton, PA, August 13, 1924, pg. 19.

[33] “ENLARGE MILL AND VILLAGE 50 PERCENT”, Asheville Times, November 9, 1928, pg. 1.

[34] Textile World, : Vol 75 Issue 25, June 12, 1929, pg. 67 (3937).

[35] Asheville Times, December 1, 1929, pg. 1.

[36] “Beacon Manufacturing Plant To Be Enlarged”, Asheville Citizen-Times, January 18, 1933, pg. 1.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] “BEACON TO RAISE PAY THIS WEEK”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 14, 1933, pg. 1.

[40] Asheville Times, October 29, 1936, pg. 1.

[41] “BEACON FIRM BUYS MILL IN S. CAROLINA”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 12, 1937, pg. 1.

[42] “BLACK MOUNTAIN HIGHWAY ROUTE GIVEN APPROVAL”, Asheville Times, August 13, 1940, pg. 8.

[43] “NEW WATER LINE TO SERVE HOMES AT BEACON PLANT”, May 22, 1940, pg. 16.

[44] “DEFENSE CONTRACT”, Winston-Salem Journal, Winston-Salem, NC, November 4, 1941, pg. 14.

[45] Beacon Men In Service Get Christmas Gifts”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 29, 1942, pg. 6.

[46] “Beacon Employees Serving In War Will Receive Yule Boxes”, The Asheville Times, September 30, 1943, pg. 20.

[47] Quoted from the code in: Building the Workingman’s Paradise: The Design of American Company Towns”, by Margaret Crawford. (New York, NY: Verso, 1995) pg. 202.

[48] Ibid.

[49] “BEACON SELLING 231 DWELLINGS TO EMPLOYES [sp]”, Asheville Times, October 14, 1948, pg. 12.

[50] “Beacon Sells 162 Dwellings For $457,500”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 23, 1948, pg. 1.

[51] Ibid.