Gone forever from thy borders, But immortal in thy name, Are the Red men of the Forest!Be thou Keeper of their fame! Paler races dwell beside thee, Celt & Saxon till thy lands…– poem, “Swannanoa: Nymph of Beauty”

All the land now occupied by modern-day Biltmore Village and Fairview Road, along the south side of the Swannanoa River, was once the home and plantation of one of Buncombe County’s earliest settlers, Thomas Foster, and later became the homeplace of Reed family, before being sold to George Vanderbilt and developed as Biltmore Village.

WM. FORSTER & THOMAS FOSTER FARMS

William Forster, the father of Thomas Foster (Thomas decided, as an adult, to drop the ‘r’ in his name), above-mentioned, was the son of William Forster and Mary Forster, his wife. William was born in Ireland on March 31, 1748 and emigrated to Virginia as young man. After the close of the Revolutionary War he removed with his family to Western North Carolina, where in 1790, he purchased a 640 acre tract from William & James Davidson for “200 pounds”.[1] Following the Revolutionary War the State of North Carolina disposed of lands formerly owned by the Crown and also by individuals such as the Earl of Granville, one of the largest British land owners. Under the state law settlers could locate unsettled land and claim it. A settler was authorized to claim up to 640 acres and an additional 100 acres for a wife and for each additional minor child. The Davidson tract, which William Forster purchased was on both sides of Swannanoa, about two miles south of the center of modern-day Asheville, at what is now the area known as Biltmore Village. According to the early twentieth-century historian, Foster A. Sondley (a direct descendent of Thomas Foster), William’s residence was on the north side of the river, “standing where is now the northern end of the Swannanoa Viaduct at the foot of the hill.” [2] I would interpret Sondley’s description of the location of William’s residence, for modern-day readers, as approximately near the intersection of Short McDowell Street and Meadow Road, actually under the Viaduct. Most likely William’s residence was a log house, and as was the tradition at the time, I would guess that it was one and a half stories (the upper floor being an unheated loft).

It’s worth noting that on his land, William “permitted to be built, and used without charge, the Union Hill Academy, afterwards Newton Academy of which he was a trustee”. [3] The academy was established before 1793 as Union Hill Academy, with Robert Henry as the first schoolmaster. In 1797 the Reverend George Newton, a Presbyterian minister, took over the school that would later bear his name. The academy was located on the east side of modern-day Biltmore Avenue at Unadilla Avenue, next to the Newton Academy Cemetery (which is all that remains of the former school).

Thomas Forster was born to William Forster and his wife Elizabeth Heath Forster, on October 14, 1774, in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, prior to the family’s immigration to Western North Carolina. Thomas was a pre-teen when his father moved the family to the banks of the Swannanoa River and so was raised on his father’s farm. In 1796, at the age of 22, Thomas married Orra Sams, the daughter of Edmund & Nancy Sams. In 1802, William Forster, for “Fifty-dollars”, sold the lower half (on the south side of the Swannanoa) of his farm to Thomas and his growing family. [4] Although the deed does not specify the acreage, I believe it was approximately 300 acres. With subsequent land grants and land purchases, Thomas was able to extend his property east to include most of the land on both sides of Fairview Road, between the Swannanoa River and Sweeten Creek, and south to include Busbee Mountain in modern-day South Biltmore.

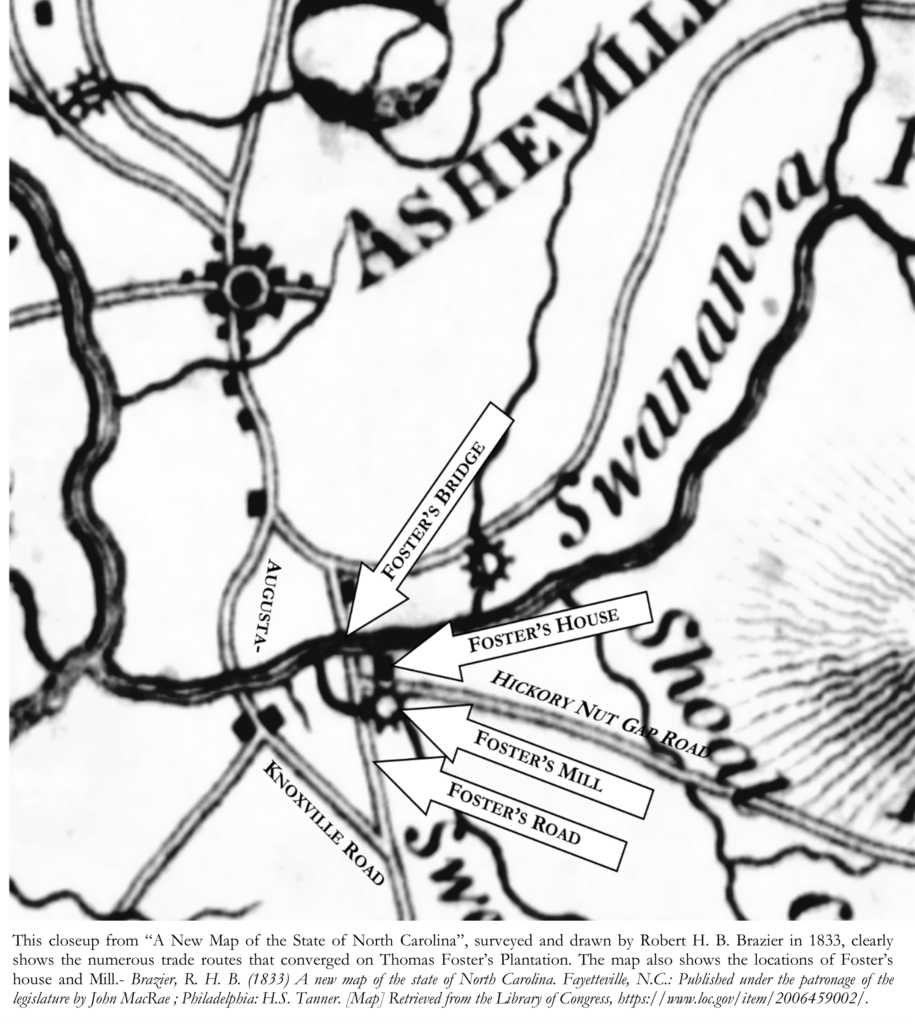

It seems that Thomas Foster (as he was now known) had chosen a very strategically located property near the Drovers Road, which bordered his father’s property to the north, north of the Swannanoa River. The Drover’s Road passed by William Forster’s house and then crossed the Swannanoa River at the bridge on Col. John Patton’s property, which was adjacent to Thomas Foster’s property on the west. Col. Patton benefitted from the trade and commerce generated by the road, but Foster did not. Therefore, shortly after his father sold him the property, in order to cash in on the business generated by the Drover’s Road, Thomas Foster decided to take measures to reroute the drovers on to his property by building a bridge across the Swannanoa River, about one hundred yards above the present Biltmore bridge, just east of where the Sweeten Creek empties into the Swannanoa. To divert those using the existing road to his new bridge, he constructed a road (like a modern bypass) from the Drovers Road (where it turned southwest) where Biltmore Avenue now runs—from the point at the Newton Academy Cemetery on Biltmore Avenue to the foot of the hill near the river, where Foster’s new road then circled the foot of the hill to the east to his bridge. I believe this followed what is now Bryson Street and Swannanoa River Road. From his bridge, he continued his new road along Sweeten Creek on his property, before looping the road in a southwesterly direction reconnecting it with the Drovers Road (old Augusta-Knoxville Road) about where Interstate 40 now crosses Hendersonville Road. The rivalry between him and Thomas Foster in the business of feeding stock upon their two several roads now became fierce, though not unfriendly. When the Buncombe Turnpike road opened in 1828, the route adopted was the road by Col. John Patton’s. [5]

The old Rutherfordton Road, which ran from Rutherfordton to Asheville, also crossed Foster’s property. Although road was established early in the settlement along the Swannanoa River, it remained rather primitive until 1822. In 1822, Civil Engineer Hamilton Fulton of the North Carolina Board of Internal Improvements submitted his report to the State General Assembly. His report not only included reports on projects which had already been approved by the General Assembly, but he also included reports on “Proposed Roads”. After reporting on the Saluda Gap Road, which would later become part of the Buncombe Turnpike, Fulton submitted a report on a proposed “Road from Asheville to Rutherfordton”:

“The Saluda Gap Road is situated too far to the South, for the direct line of intercourse between Kentucky, Tennessee, and Charleston. It has proposed to open a road from Asheville over the Hickory Nut Gap to Rutherfordton. If this road were opened, it would not only be the nearest, but therefore been it would afford the growers of produce an opportunity of transporting it by water down the Broad River, to Columbia, Charleston, &c etc. I did not examine that part of the road from Asheville to Mrs. Ashworth’s; but from information on which I can rely, there is a tolerably good road, requiring no other improvements than what can be effected by the statute labour of the neighborhood”. [6]

Fulton’s report indicates that a decent road already existed from Asheville to Mrs. Ashworth’s, whose place (according to Fulton) was at the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains only one-and-half miles from the ridge at the Hickory Nut Gap. In 1824, Fulton’s recommendations were officially approved by the North Carolina General Assembly in “An Act Authorizing and Making and Improving A Road from Asheville to Rutherfordton”. [7] Fortunately for Thomas Foster, the new road, which was named the “Hickory Nut Gap Road”, connected with his new road and bridge, all on his property. In fact, in 1838, when it was proposed to establish the Hickory Nut Gap Road as a turnpike (toll road), it was reported that the new turnpike would run from “Cool Creek in Rutherford County to Thomas Foster’s in Buncombe County”. [8] Also, in 1824, the legislature of North Carolina incorporated the Buncombe Turnpike Company, directing James Patton, Samuel Chunn and George Swain to receive subscriptions for the laying out and making a turnpike road from the Saluda Gap, in the county of Buncombe, by way of Hendersonville, Fletcher, Asheville and the Warm Springs, to the Tennessee line. The Turnpike followed the old Drover’s Road and was completed and opened in 1828.

Foster took advantage of his strategic location by establishing what would become known as “one of the best Stands in the upcountry”, [9] where the drovers and their animals could obtain food and rest. Thomas Foster took it a step further and built a “grist and saw” mill where he could then sell the corn and grain back to the farmers and drovers in the form of ground corn meal and flour. Foster built his Mill on the northeast side of Sweeten Creek, in a small triangle of land where the Hickory Nut Gap Road joined his road [I’ve named it Foster’s Road]- certainly a very advantageous location. Modern-day readers would recognize the Mill site as the current location of the French Broad River Brewery, on the southside of Fairview Road where the road crosses the creek and railroad tracks. The mill was operated by a waterwheel, with water supplied from a millpond and mill race which came off Sweeten Creek on its northside) further south of the mill, paralleling the current Sweeten Creek Road.

Also living and working on the Foster farm were several enslaved individuals who also helped run the mill, stand, and farm, and served in the house. It’s impossible to know all of their names, but here a just a few that I have gathered from various sources (deeds & wills): Jerry (33 yr. old male-5’3” in 1800); Spencer; Lucinda and child, Ann; Phillis (age 16 in 1825, mulatto girl); and Jane.

Thomas Foster built his house just across the Hickory Nut Gap Road from his Mill. Although we have no description or photo of the house, I would assume from a study of other contemporary houses and inns, that his house started as a one-story log cabin with a sleeping loft but quickly accumulated various additions with the growth of Foster’s family and business. Today’s readers would recognize the house site as being in front of the Davis Home Furniture Store at 100 Fairview Road. Foster Sondley, historian, tells us that Foster also later built an additional small home on his property for his aging in-laws, Captain Edmund Sams and his wife. We have no idea of the location of the Sams’ house.

A noted visitor to Thomas Foster’s house was Methodist bishop, Rev. Francis Asbury. On his numerous travels to the Mountain churches during the first years of the nineteenth-century, he often visited Thomas Foster’s farm. Thomas Foster was a Universalist, not a Methodist, but as Asbury always chose to cross the Swannanoa at Foster’s (no doubt because of Foster’s bridge), Foster was gracious to allow Asbury to hold meetings at his house. A record from Asbury’s journal shows that he first visited Foster on Sunday, November 9, 1800 where Asbury noted: “We came to Thomas Foster’s and held a meeting at his house”. [10] A few days later, after traveling further north to “Killian’s” (Killian’s house remains on Beaverdam Road in North Asheville), Bishop Asbury returned south on Tuesday and lodged at Foster’s house again. Besides the other lodgers who were “good company”, Asbury noted that they were also accompanied by “horses in a drove of thirty-three”. [11]

Besides being a farmer, hotel-keeper, and Mill-owner, Thomas Foster was also a major civic leader of North Carolina, serving as a member of the House of Commons in the General Assembly of North Carolina from Buncombe County in 1809, 1812, 1813 and 1814, as well as representing Buncombe County in the Senate of the State in 1817 and 1819.

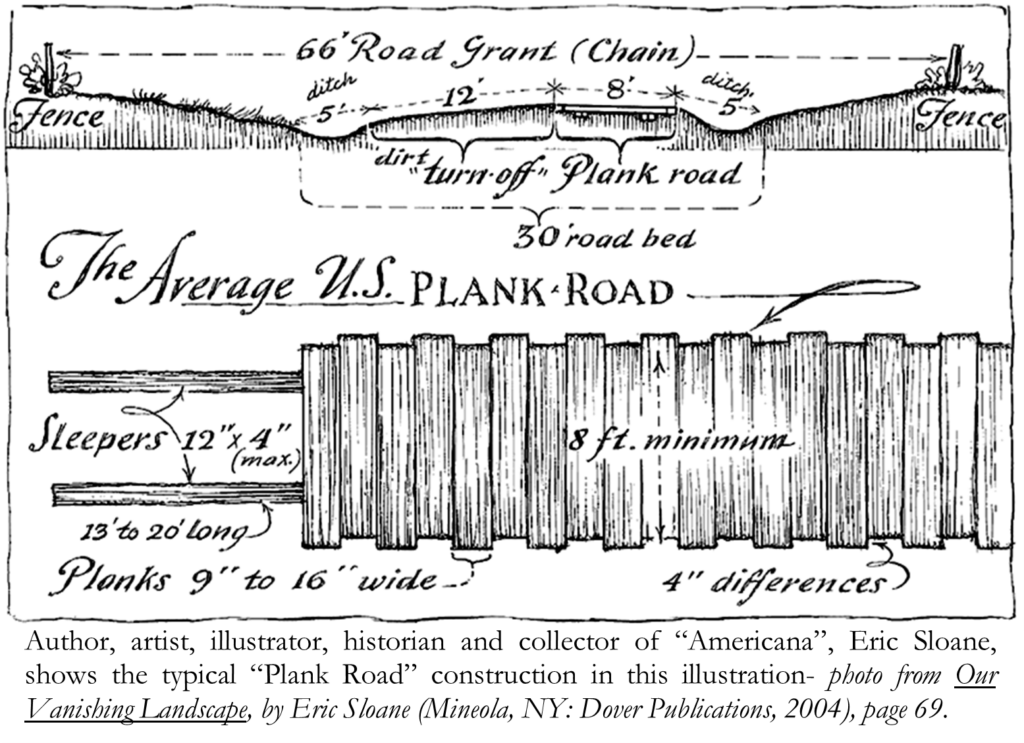

The “Asheville-Greenville Plank Road Company” was incorporated in 1851 to construct a road from Asheville south to Greenville, SC. A plank road was constructed using thick oak planks, creating a wood plank floor surface to drive on. Although the company was authorized to use any part of the Buncombe Turnpike, it deviated at one or two places. Although the Plank Road followed what is now Biltmore Avenue south from the public square, instead of following the Turnpike west through Col. Patton’s lands or turning east to Foster’s bridge, it was constructed halfway between the two properties, forming what is now Biltmore Avenue-Hendersonville Road through Biltmore Village. Thomas Foster was ill when construction began on the road through his property. According to the story, Foster “told the representatives of the new road to proceed and when he recovered, he would let them know what damages he claimed. When their agent, Mr. A. T. Summey, came to inquire how much damages were claimed Captain Foster said that they had not damaged him at all.” [12]

Thomas Foster died on December 24, 1858 at the age of 84. In his 1847 will, Thomas left the “house, out buildings, and mills” and a portion of his lands to Orra, but since she predeceased him, his executors decided to auction off the entire 700-acre farm, including the house, mills and other outbuildings on August 25, 1859. It was reported that James C. Davidson was the purchaser. However, I believe that he may have defaulted on his purchase, as the property was put up for sale again by the executor, George C. Alexander, in 1862. At that sale, John Woods Woodfin purchased the property.

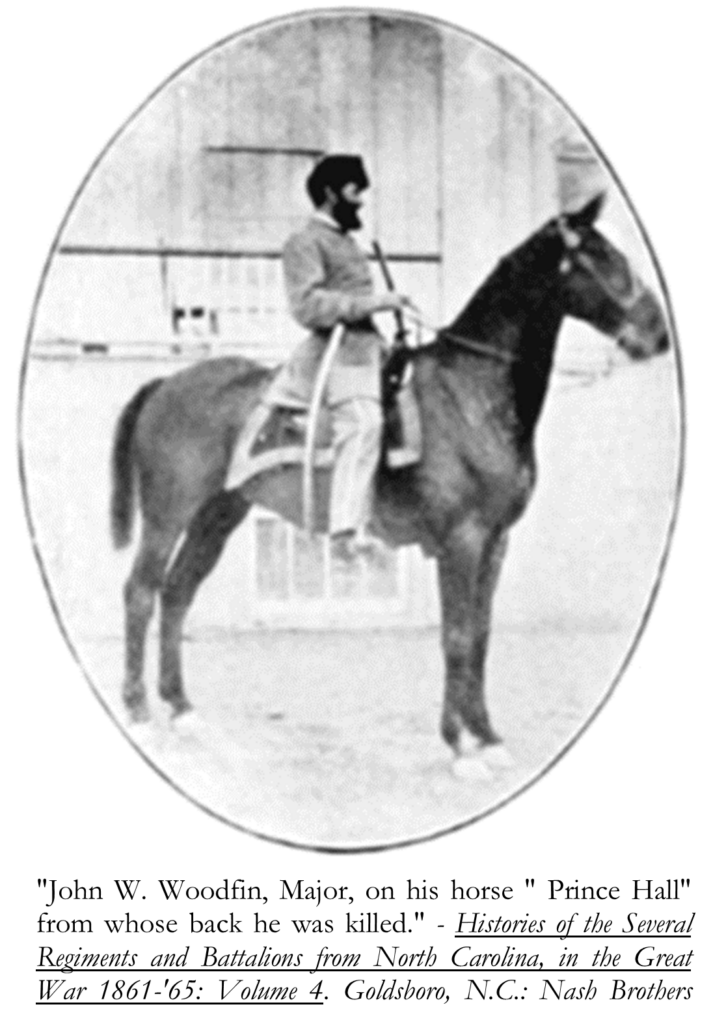

Woodfin, one of the wealthiest men in Buncombe County, owned fifty-four slaves and was noted as a lawyer and progressive agriculturalist. In May 1861 he was appointed captain of the “Buncombe Rangers,” subsequently Company G, 9th Regiment N.C. State Troops (1st Regiment N.C. Cavalry). In September 1861 Woodfin was promoted to major and transferred to the 19th Regiment N.C. Troops (2nd Regiment N.C. Cavalry). Woodfin resigned because of ill-health on September 6, 1862 and returned to Buncombe County. He then organized a three-company local defense force known as Woodfin’s Battalion N.C. Cavalry. In October 1863 a force of several hundred Federals under the command of George W. Kirk, an East Tennessee partisan, occupied Warm Springs [present day Hot Springs], a resort in Madison County. Woodfin’s Battalion was then at Marshall, the county seat of Madison, and Woodfin led his outnumbered command against the raiders. Kirk’s men occupied the Warm Springs hotel and waited in ambush for the Confederates.

During the march to Warm Springs, Woodfin took time to pen a letter to his brother, Nicholas Woodfin. Aware that his battalion was outnumbered, he nevertheless observed that “Badly prepared as we are I see there is not much inclination to surrender or retreat on the part of our leaders or men.” Woodfin then directed his brother how to dispose of his property in the event of his death, leaving it all to his wife and niece (both of whom were named Mira): “I want Mira to have and hold all I possess in my own & her right during her life, remainder to our little Niece Mira. . . .”. Woodfin concluded the letter by observing that “I am in a hurry because the boy is waiting and fear the mail will leave us. The increased roar of cannon since I began writing warns me too that I must among our men.”

Woodfin, mounted on his charger “Prince Hal,” rode ahead of the battalion with a few members of his staff. Some of Kirk’s men occupied a nearby outbuilding and delivered a sudden volley. Woodfin was “blown off his horse” and instantly killed. His men, shocked and dismayed, hastily retreated to Marshall. Woodfin’s body was recovered the next day at the place where he had fallen, stripped of his valuables. In the Buncombe County Minute Docket Court Pleas & Quarter Sessions, November 1863, Woodfin’s letter to his brother was probated as his last will and testament. [13]

Following Woodfin’s death, his wife Mira retained her life estate of the property, but did not continue to live there, instead she leased the property, “Land and Mills” [14] to Dr. John A. McDowell. But then in 1868, Woodfin’s son and executor, Nicholas W. Woodfin, sold the property to Samuel Whedbee.

JOSEPH REED HOUSE

In 1872 the old Captain Thomas Foster Plantation was purchased from the Samuel Whedbee estate by 45-year-old Joseph Reed, a local blacksmith and entrepreneur. Reed, like Foster, would eventually maximize the property’s strategic location at the merging of two major trade routes, and would even see the merging of a third route from the east.

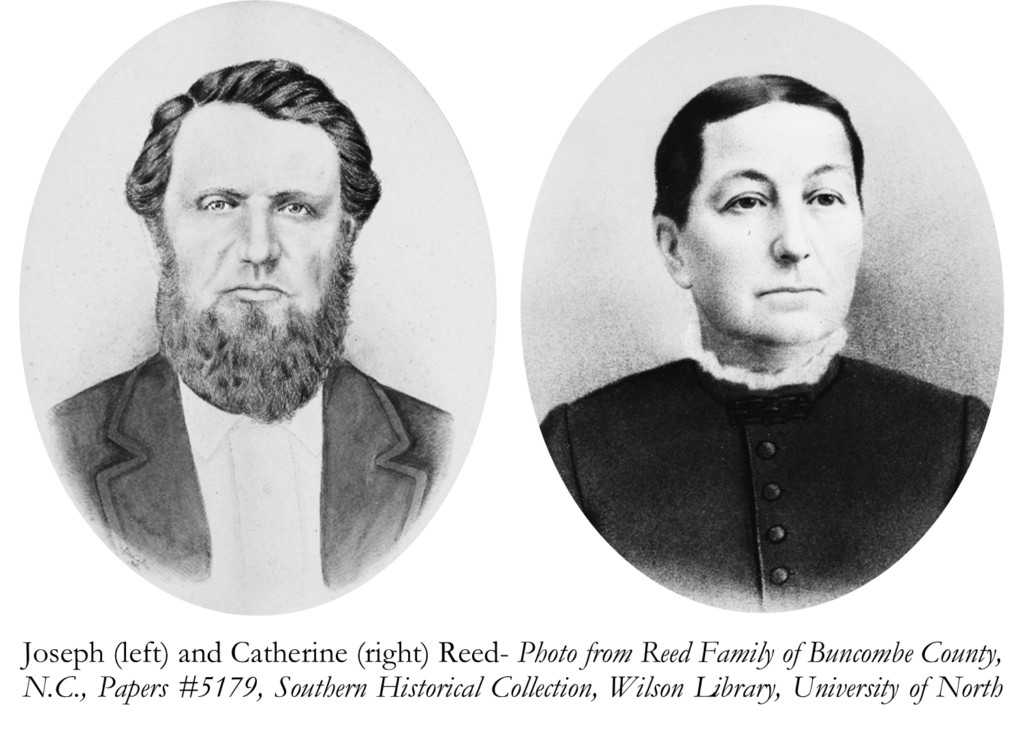

Joseph Reed was born in Gap Creek, South Buncombe County, on May 7, 1827, the son of John Reed (1802-1885) and Lavina McBrayer (1807-1875). Joseph Reed’s grandfather was Eldad Reed II (1768-1849). In 1849, Joseph married Catherine Harrison Miller Reed, a descendant of the Harrison family of Virginia, which produced two United States Presidents: William Henry Harrison and Benjamin Harrison. Joseph grew up in Gap Creek, but shortly after their marriage, Joseph and Catherine settled on Gashes Creek, where his father John Reed had moved in the 1840’s. In 1854, Joseph and his father helped found Gashes Creek Baptist Church. Gashes Creek Baptist Church and its adjacent churchyard (cemetery), just south of Interstate 40 off Asheville-Charlotte Highway, remain in use.

Like his father, Joseph took up trade as a blacksmith. During the Civil War, Joseph served as a captain at the Asheville Armory and as a guard against raiders and bushwhackers. At the close of the War, he returned to his blacksmithing, but was soon feeling discontented, and so, beginning in 1869, he began expanding his land holdings. He soon owned large tracts of land in Buncombe County. In 1871, he sold some of his accumulated land in Cane Creek (Gap Creek) and Gashes Creek and purchased a house on Main street in Asheville, [15] where he opened a store, “Jos. Reed & Sons”. In 1872, he purchased the “old Capt. Foster’s place”, a 640-acre farm, two miles south of Asheville, across the iron bridge on the south-side of the Swannanoa River (modern-day Biltmore Village and Fairview Road). [16]

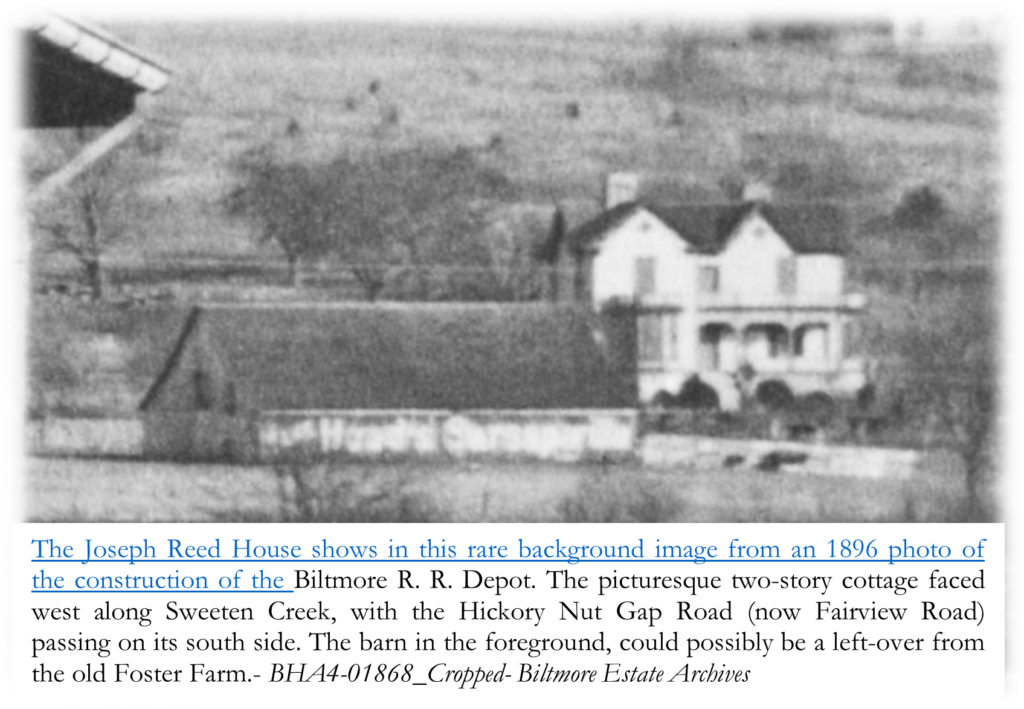

Author and Reed descendent, C. Bruce Whitaker, writes that “Joseph Reed tore Thomas Foster’s house down and built a new house for himself.” [17] The location of Reed’s new house matches very closely the location of Foster’s house shown on the Brazier’s 1833 map, which initially led me to believe that Joseph may have kept and enlarged Foster’s old house. However, I now suspect that Whitaker is correct, and that Joseph probably lived in the Foster house while building his new house right next door, then demolished the old Foster house after completion of the new home.

Joseph and his wife Catherine chose the prevailing Picturesque and Cottage Orne’ styles, first popularized in the 1840’s by landscape architect, and promoter of Romantic ideals, Andrew Jackson Downing. Architectural historian, Catherine Bishir tells us that “the values and models espoused by Downing and his successors gained wide exposure in national agricultural journals and found their way into the North Carolina press. Such progressive periodicals as the Farmers Journal, the Arator, and the Carolina Cultivator ran plates and texts from Downing’s books […]”. [18]

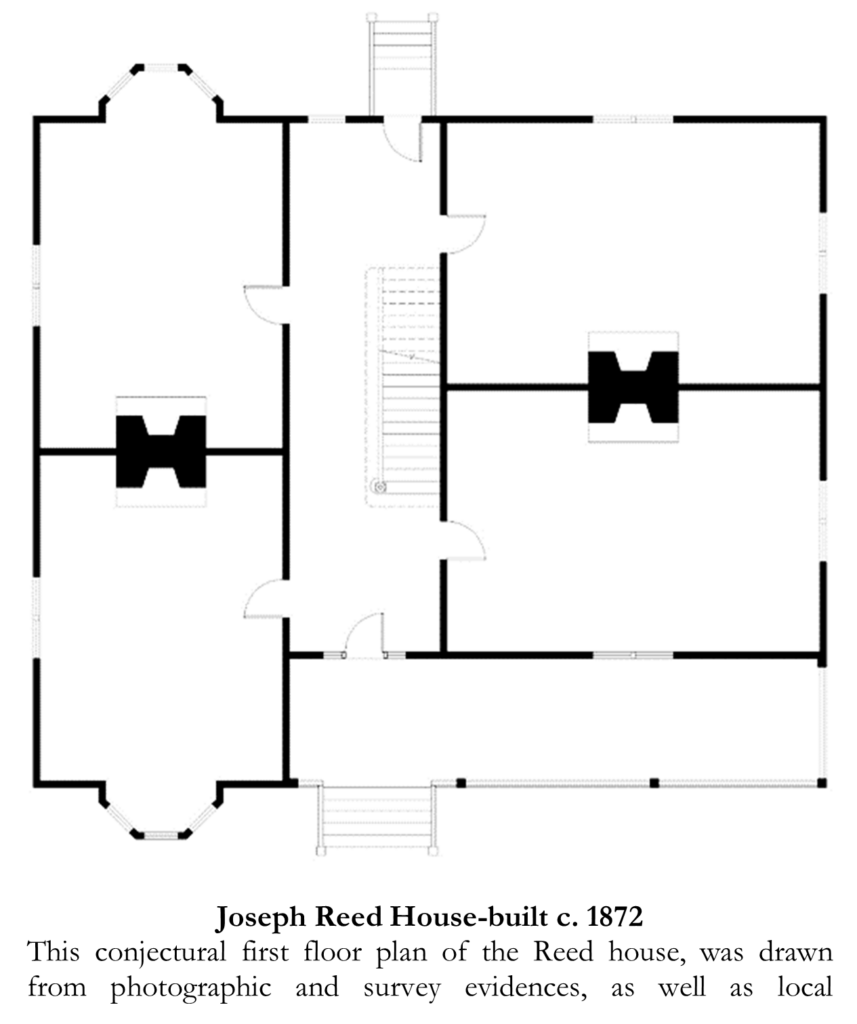

By the early 1870’s, when Reed was building his house, local builders had mostly adopted Downing’s styles for residential projects. From photographic evidences, and outlines from the 1925 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, it appears that the Reed house was a double-pile with bay, two-story house. Two rooms flanked a center entrance/stair hall on each floor. But unlike the Georgian style double pile house with its bi-lateral symmetry, the Reed house exhibited the asymmetry of the Picturesque Style, with the rooms on the northside of the house being narrower and projecting to the west forming a gabled bay. A charming five-sided bay window projected on the first floor on this bay, no doubt signifying a formal parlor. The bracketed/trellis veranda was also a hallmark of the picturesque cottage style.

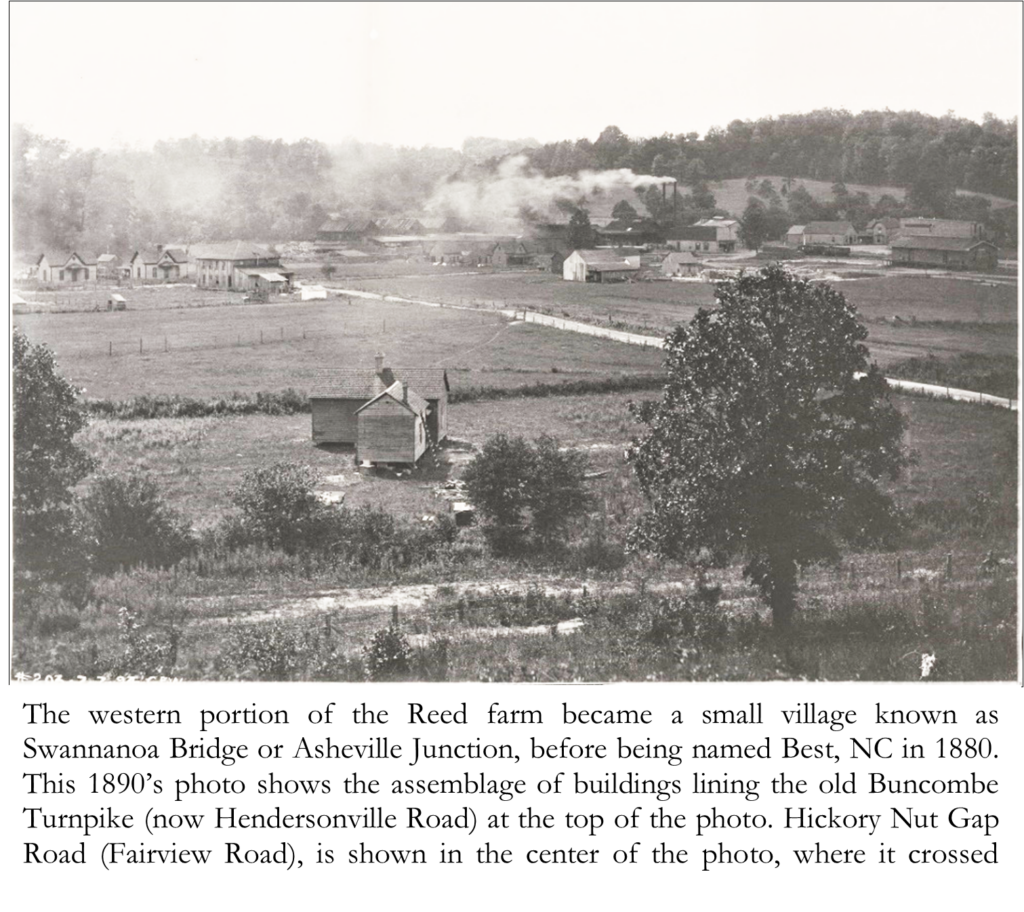

The Capt. Foster property already had an operating grist and sawmill, located along the Hickory Nut Gap Road, which intersected with the Buncombe Turnpike on the property. But Reed, perhaps hoping to pick up business from the many travelers, also built and opened a general merchandise store along the Turnpike. Soon an array of other buildings began to grow around the store, forming the nucleus of a village. The area began to be called “Swannanoa Bridge”. By the late 1870’s it became evident that Reed’s property would soon become even more strategic.

An act to incorporate the Western North Carolina Railroad Company was ratified by the North Carolina General Assembly on February 15, 1855. The railroad opened Fall 1858 with an 84-mile line from Salisbury to within four miles of Morganton. [19] But the Civil War virtually halted construction. After the war, in 1866, the State subscribed $4 million to the Western North Carolina Railroad to continue the project. John A. Hunt finished the rest of Charles F. Fisher’s work east of Morganton, and plans were made for completion of the next section from Morganton to Old Fort. Major James W. Wilson, a young engineer, was hired to complete the section from Morganton to Asheville. By 1869, Wilson completed the road to three miles west of Old Fort, until he was suddenly halted due to scandal. With no ready cash on hand, the railroad’s president and stockholders were eager for governmental aid. The state constitutional convention of 1868 and the Republican State Convention authorized the issuance of bonds totaling $6.4 million to extend the road from Morganton to Asheville., they also ratified an act on August 19, 1868, reorganizing the existing Western North Carolina Railroad as the Eastern Division — from Salisbury to Asheville — and a new company the Western North Carolina Railroad, Western Division — composed of two future lines, one to Paint Rock and the other to Ducktown, Tennessee. To build the Western Division, bonds were authorized for sale and thus a great scandal was born. [20] In the same year, George W. Swepson and Gen. Milton S. Littlefield secured absolute control of the Western North Carolina Railroad by purchasing 2,000 of the 3,080 bonds issued. The railroad then became a victim of Swepson and Littlefield’s corruption. During the administration of Governor William W. Holden, the two men issued worthless securities, participated in fraudulent stock subscriptions, and built a huge debt. The road was pillaged, Littlefield and his cronies fled the state in 1870, and Holden was impeached. After the so-called Littlefield scandal, the state bought the Western North Carolina Railroad for $665,000 in 1870. But after a seven-year lull, and a reorganization of the railroad, in 1878, Wilson was furnished with 500 incarcerated laborers and the appropriate funds to continue construction on to Asheville. Wilson’s brilliantly designed looped track up Old Fort Mountain to traverse the 891 feet change in elevation, and his ingenious idea to bore the 1,832 feet long Swannanoa Tunnel from both ends simultaneously, enabled the line to quickly approach Asheville by 1879. [21]

An article in the October 16, 1879 Asheville Weekly Citizen, announced that the goal of the WNCRR finally reaching Asheville “has been almost reached”. However, it also reported that the Swannanoa Tunnel, as of October 1st, still had “147 feet to be removed”, but that meanwhile track was being laid “on this side of the mountain”, east toward Asheville, and was expected to be completed to Gudger’s Ford (six miles from Asheville) in six weeks. [22]

The above mentioned article also reported that “a stockade has already been built on the Reed farm near Swannanoa bridge, a little over a mile from the corporate limits, and the work at this end will commence either this week or next.” [23] It was further reported “that Mr. Joseph Reed, through whose farm the road is to run a considerable distance, has tendered the right of way, and agrees to erect a depot at or near the bridge, if the company thinks it fit to establish a depot there.” [24] The commissioners did accept Joseph Reed’s offer, however, a sudden turn of events intervened causing it to be an additional year’s time before the railroad was to reach “Asheville Junction” (the Railroad’s name for the depot at Swannanoa Bridge).

On April 27, 1880, the state decided to sell the Western North Carolina Railroad at public auction to William J. Best and Associates with the stipulation that the planned lines be completed as scheduled—from Asheville north to Paint Rock, TN by July 1, 1881, and a line west to Ducktown, TN by January 1, 1885. The auction and reorganization caused a slowdown in construction, but the railroad finally reached Asheville Junction (on Joseph Reed’s farm) in October of 1880. [25]

Despite the political wrangling, Joseph Reed continued his preparations for the railroad’s arrival, by beginning construction on his promised depot building. In April of 1880, he began work on the 30 feet by 100 feet brick depot. The depot was being built “100 yards south of Porter & Shope’s Store” and would include a passenger room and ticket office. [26] The new depot was to be called “Asheville Junction Depot”. [27] At the same time that the new depot was being built, it was announced by the Post-Office that they were establishing a post office at Swannanoa Bridge, “to be known as the “Best” office”. [28] This name conundrum was best summed up in the entry for “Best” in the 1883 The Asheville City Directory and Gazetteer of Buncombe County: “Called Asheville Junction by the RR Co. and Swannanoa Bridge by everybody else, but Best by the Postoffice Department.” [29] The “everybody else”, mentioned in the directory’s description, included the directory’s compiler, J. P. Davison, who was himself a Swannanoa Bridge resident!

While the Western North Carolina Railroad was struggling to complete its line from the west, another railroad from the south joined in the race to Asheville. Despite a pre-Civil War failed attempt, the Spartanburg & Asheville Railroad was chartered in 1873, with construction commencing in 1876. This railroad had to traverse the steeply graded Saluda Mountain, causing construction to go very slowly. Then the railroad went through a reorganization in 1881 and was renamed the Asheville & Spartanburg Railroad, causing additional delay. It was not until 1886 that the line was finally completed with its tracks joining and merging into the Western North Carolina Railroad line at Asheville Junction. The Asheville & Spartanburg Railroad ran through Joseph Reed’s property, passing directly by his Mill and house just before merging into the Western North Carolina Railroad (also on his property).

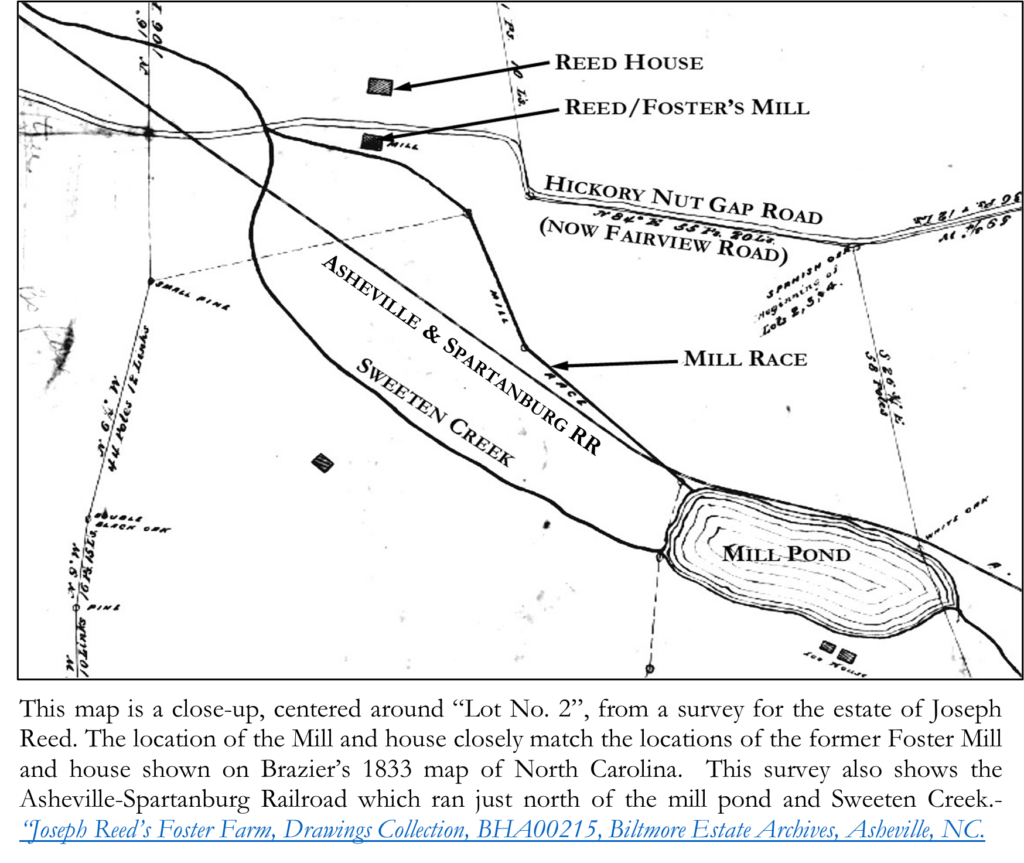

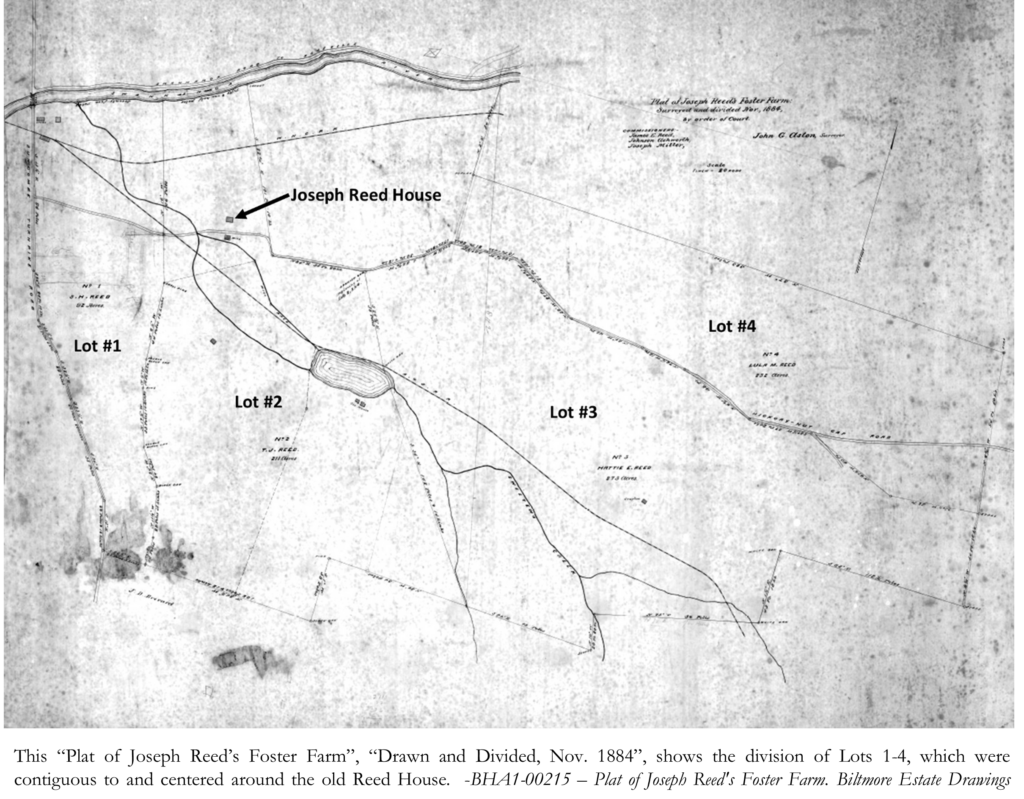

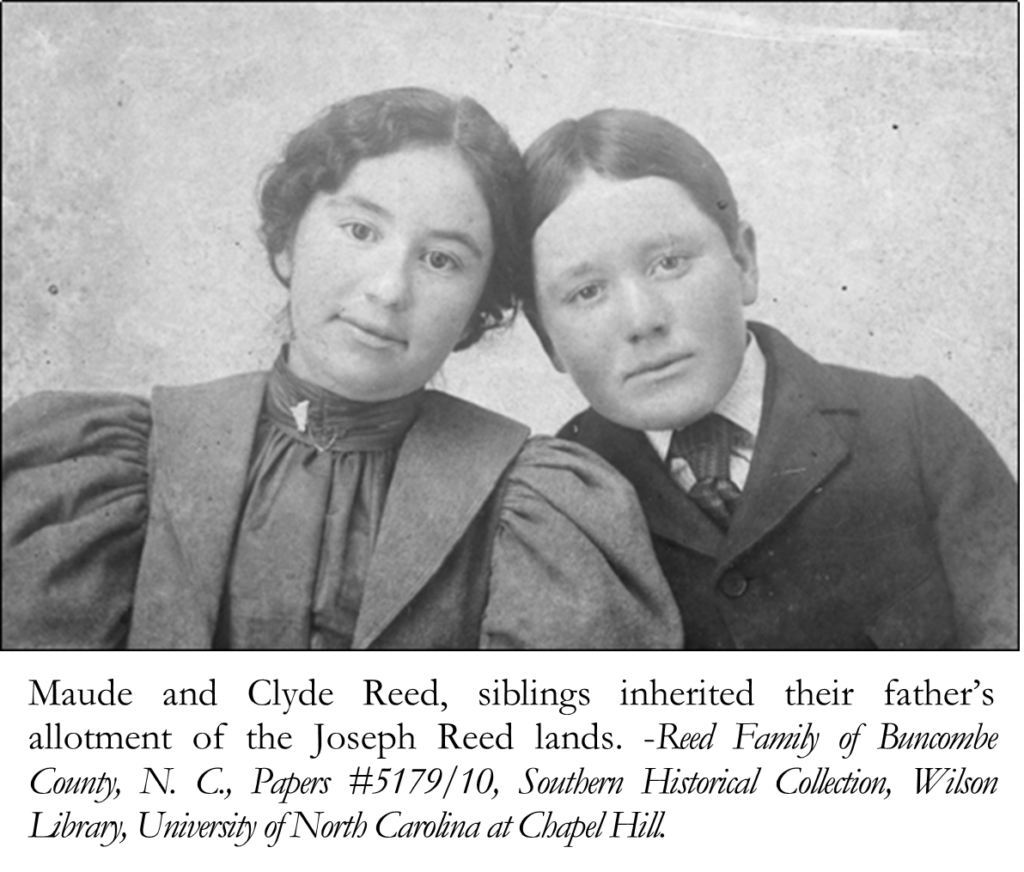

Joseph Reed died intestate on August 22, 1884. In October of 1884, Catherine and their surviving children, Samuel Harrison Reed (1851-1905), Marcus Lafayette Reed (1853-1938), Thomas Jefferson Reed (1860-1903), Loula Martin Reed (1864-1889) and Harriet Katherine Reed (1869-1967), petitioned the Court for an equitable division of the estate. [30] The commissioners, James E. Reed, Johnson Ashworth, and Joseph Miller appointed by the court, officially divided the estate into five “Lots”. They hired surveyor John G. Aston to survey and draw a “Plat of Joseph Reed’s Foster Farm”, “Drawn and Divided, Nov. 1884”, [31] which showed the division of Lots 1-4, which were contiguous, and centered around the old Reed House. “Lot No. 5”, which was allotted to Mark L. Reed, was not shown on that survey, as it was not contiguous to the others. In fact, “Lot. No. 5”, was actually two separate properties, the “Reed-Lusk Farm”, which sat further east at the mouth of Gashes Creek, and the “Joseph Reed -Busbee Mountain Tract”, which was southeast of all the other properties.

“Lot No.1”, on the extreme western edge of the Joseph Reed property, consisting of 92 acres, was allotted to Samuel H. Reed (Samuel had previously built his home, now called “Biltmore Village Inn” , on land southeast of his father’s estate in 1882). Samuel sold his lot to Charles McNamee, agent of George Vanderbilt, four years later in 1888. This lot was eventually cleared and became the site of Biltmore Village. “Lot No. 2”, which included the Reed house and mill, contained 211 acres and bordered Lot 1 on the west, was allotted to Thomas J. Reed. The commissioners also granted a dower interest and life estate for the house and lands to Catherine Reed, who was living in the house with her children, Thomas, Loula, and Hattie. “Lot No. 3”, containing 276 acres, which included most all of the land now bordering Fairview Road on the southside, was allotted to 15-year-old Hattie Reed. “Lot No. 4”, containing 232 acres, which included most all of the land now bordering Fairview Road on the northside, was allotted to 20-year-old Loula Martin Reed.

Unfortunately, Loula passed away just four years later, in 1889, at the young age of 24, and her inheritance was re-divided among her heirs. In 1891, a large portion Lot. No. 4 was purchased from the Reed heirs by Otis Miller for a new development named “Resthaven”. Although the “Resthaven” development was not very successful, it was the start of the eventual development of the land along both sides of Fairview Road, which by the 1920’s would become known as “East Biltmore” and “Oakley”.

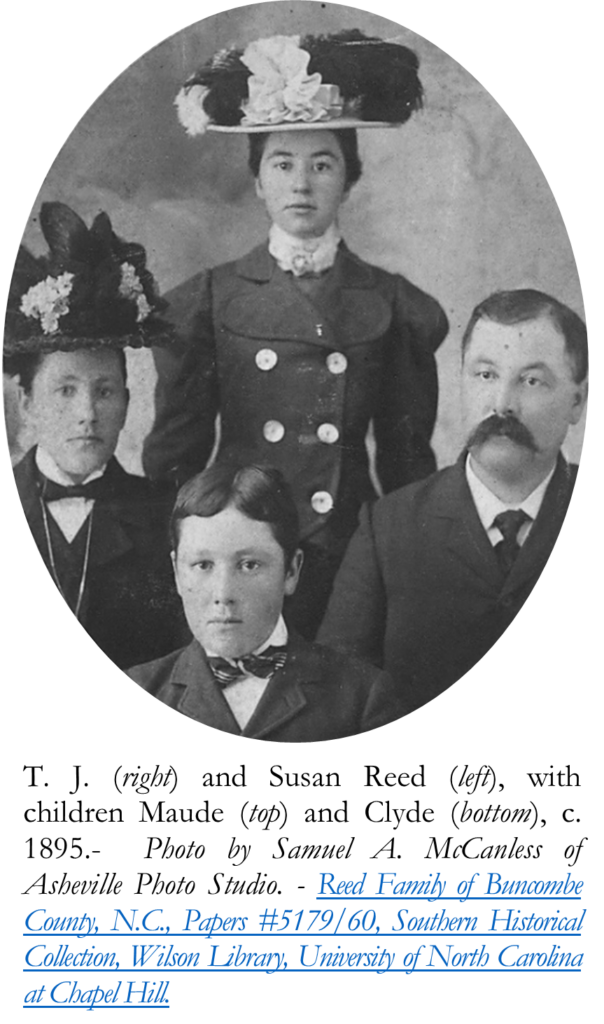

Thomas Jefferson Reed, Joseph & Catherine’s middle child, was 18 years old when his parents moved to the old Foster Farm in 1878. The following year, in 1879, Thomas married Susan B. Ashworth, daughter of Johnson & Merrill Ashworth of Fairview, NC. Thomas Reed, who at the time of the death of his father, was not only living with his parents, but actively involved in the family business. This is probably why he was allotted Lot 2 with the house and mill. In 1887, he ran an advertisement in the local newspaper, letting his “old customers” know that he was ready to prepare them with “Ice, Ice, Ice”, [32] indicating that he had been in the ice business for several years. In fact, his father, as early as 1875, was running similar ads under the name of “Jos. Reed & Sons”. The 1884 plat of Joseph’s estate clearly shows two ice houses on the land allotted to Thomas. Thomas and his brothers, Mark, Samuel, and brother-in-law, Charles Whitaker incorporated the family business in 1892 as the Biltmore Ice & Coal Company, and then in 1894, they reorganized into the Swannanoa Ice & Coal Company and built a new ice factory, not far from the family home. Then in 1898, Thomas and his older brother, Mark Reed also established and built the Biltmore Roller Mill, adjacent to the Swannanoa Ice Company. Thomas was serving as the postmaster of Best, NC when he received “official notification” that his post office would hereafter be known as “Biltmore, NC”. [33] Thomas also served as County Tax Collector from 1886-1891.

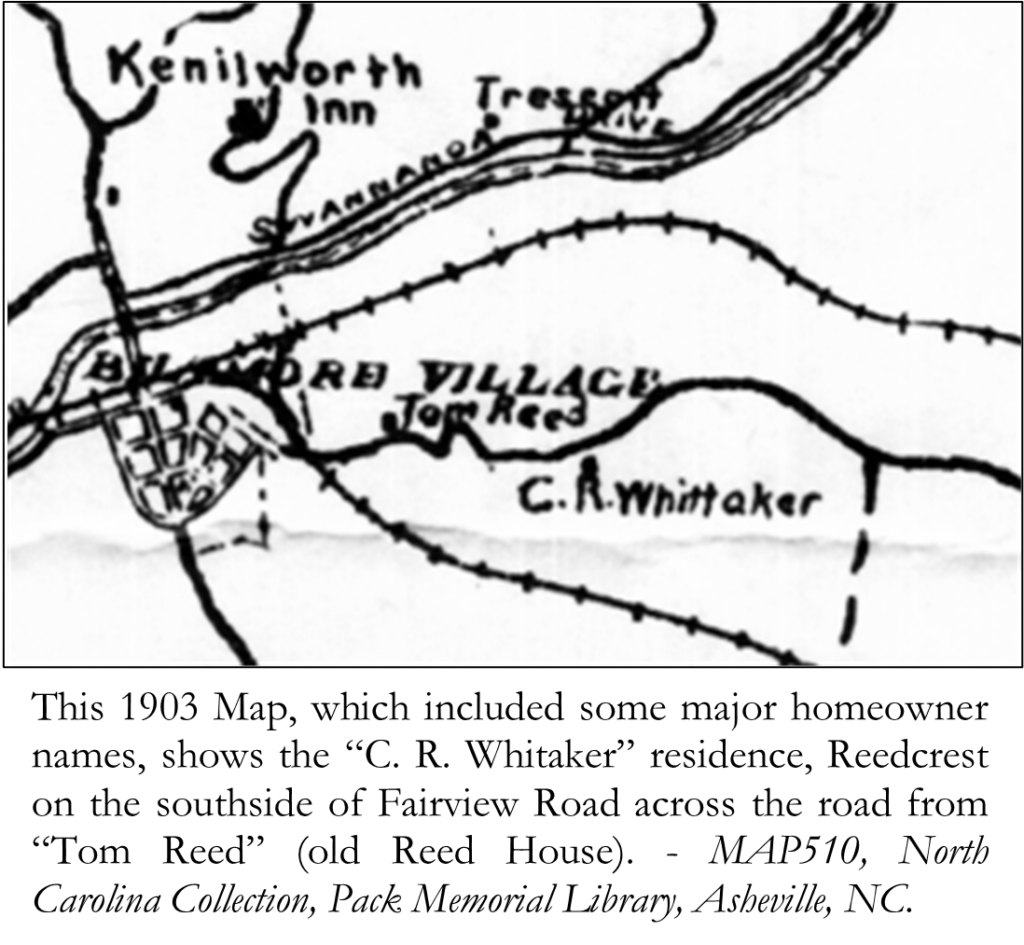

On August 3, 1903, Thomas was working in the flour mill when he suddenly felt ill and decided to go to his house to rest. The physician was summoned, but sadly, he was suddenly struck with paralysis. He died thirty hours later, on August 5th, leaving behind his wife Susan and his children Maude and Clyde, and his mother Catherine. Following Thomas’ sudden death, Catherine Reed, who had exercised her life-estate and had remained in the family home with Thomas and Susan, decided to move to live with her daughter Hattie Reed Whitaker at Reedcrest, just across the road. Catherine lived there until her death in 1907 at the age of 79.

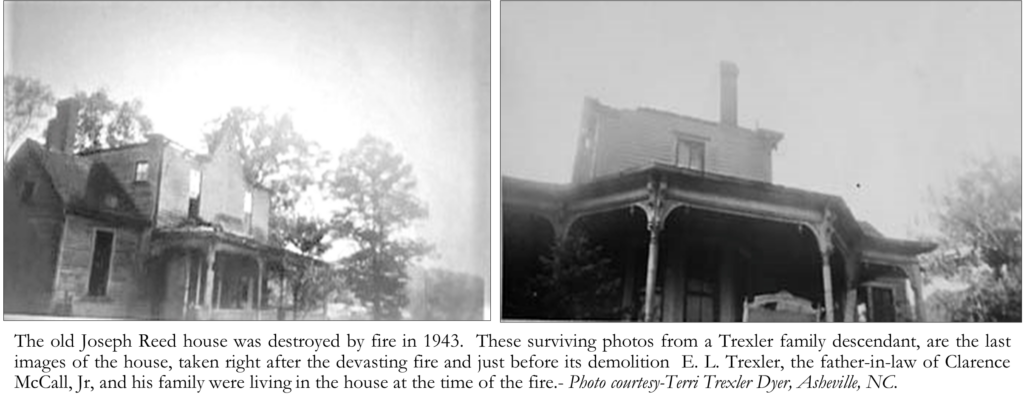

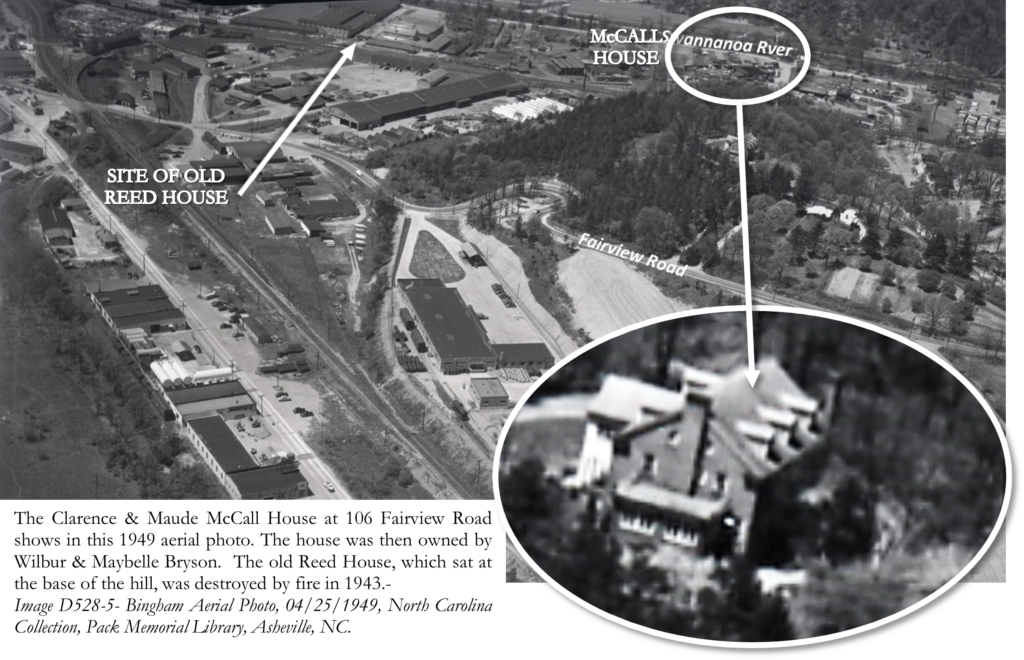

Susan, along with her two children, Clyde and Maude, continued living in the “old Reed house”, after Thomas’ death. Susan also continued to manage her husband’s estate by leasing out the estate lands to various business concerns. Upon Susan’s death in 1935, the Reed house was inherited by her daughter Maude and her husband, Clarence McCall. The old Reed House suffered a devastating fire in 1943, while being occupied by Maude’s daughter in-law’s parents, Edward L. Trexler and his wife. [34] The house had to be demolished. The site of the house is now a paved parking lot in front of the Davis Home Furniture Store at 100 Fairview Road, adjacent to a recently built massive retaining wall.

REEDCREST

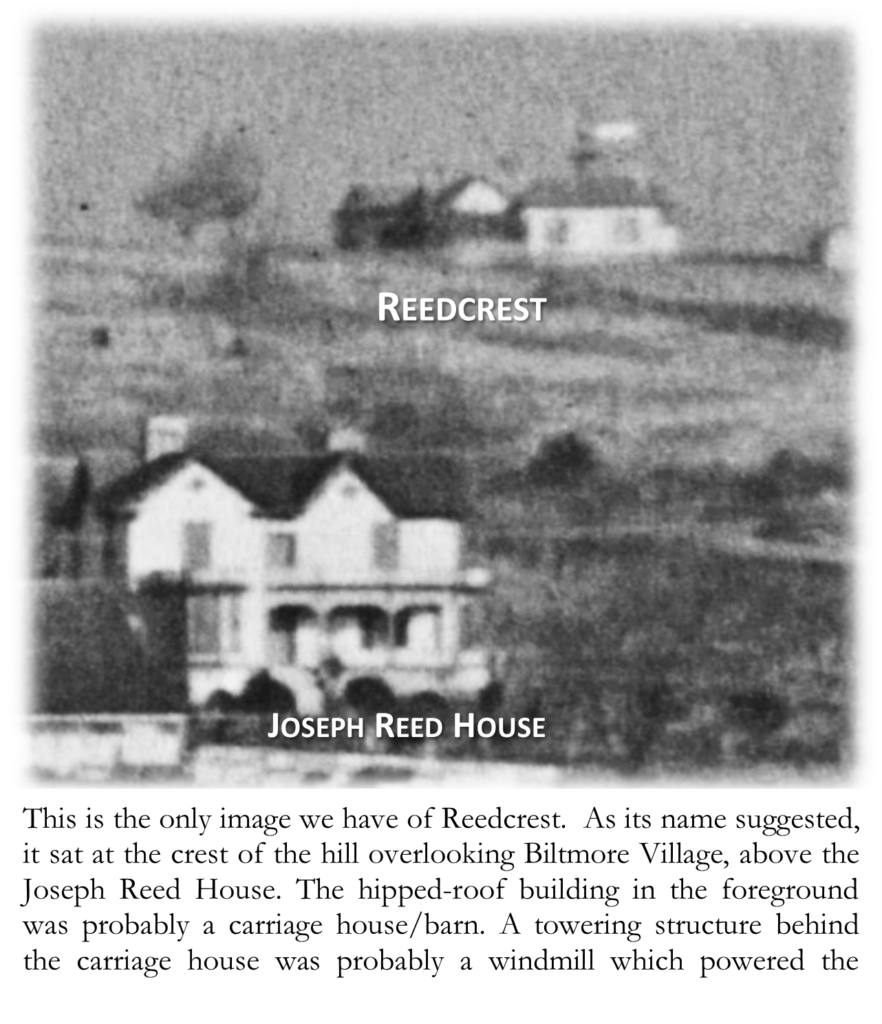

Three years after her father Joseph Reed’s death, on April 5, 1887, at age 18, Hattie (Harriett) Reed married Charles Richard Whitaker of Atlanta, Ga., who was the son of Dr. Algernon S. and Louisa Dean Whitaker. Shortly thereafter (certainly by 1894), Charles and Hattie built a large 9-room house on the crest of the hill overlooking Biltmore Village. They aptly named their home Reedcrest, as it was built on the crest of the hill that Harriet had inherited from her father, Joseph Reed. Harriet’s land included almost all the land on the south side of Hickory Nut Gap Road (Fairview Road), now known as Oakley. Harriett’s new house sat not far above her childhood home. One contemporary account described the house as “a beautiful home at Biltmore on that pretty eminence opposite Kenilworth Inn”. [35]

I have only found one blurred photographic image of the house, however, from newspaper articles and other documentation I can give some descriptive images of what it may have looked like. The photographic image seems to show that the house may have been two-stories with a two-story portico facing west towards the mountains. A hipped-roof building that shows in the foreground, I believe to have been an outbuilding, perhaps a barn/carriage house.

The earliest documentation of the house that I could find is from 1895—well not actually of the house but one of its outbuildings—the henhouse! The July 1, 1895 Asheville Citizen-Times reported that “the hennery of C. R. Whitaker at Biltmore was looted on Saturday night and 30 fowls taken.” [36] But then in 1896, C. R. Whitaker, who was involved in the Reed family businesses, decided to accept the position of manager of the Oaks Hotel on Woodfin Street in downtown Asheville. Samuel H. Reed, who was Whitaker’s brother-in-law was the owner of the Hotel. Whitaker put his house up for rent in October of 1896, and ran the following descriptive advertisement in the local newspaper:

FOR RENT- Biltmore, NC, residence which has 9 rooms and 2 halls: good range, with water connections supplied by wind mill from splendid well. Good barn and outbuildings; garden, orchard and pasture lots containing approximately 25 acres; splendid view. For more information apply to C. R. Whitaker, Oaks Hotel, Asheville, NC. [37]

The ad mentioned a windmill, which surprisingly can be seen in the photo image of the house, towering over house and outbuildings. “9 rooms and 2 halls” suggests a two-story double pile home with two rooms flanking a center hall on each floor, with the ninth room possibly being a kitchen attached to the house in the rear.

In 1897, Whitaker resigned his position at Oaks Hotel to concentrate on his other business ventures, like the Swannanoa Ice and Laundry Company, where he was in partnership with Thomas J. Reed. At that time, Charles & Hattie moved back into their house in Biltmore. Then in 1900, Hattie decided to take in boarders for extra income, a common practice during the late nineteenth-century and early twentieth in Asheville. The advertisement’s byline read: “BOARDERS WANTED IN THE COUNTRY”. [38]

The first time we see the name of Reedcrest applied to the home is in 1906, in another advertisement for boarders, although the name was first separated into two words, ‘Reed Crest’. The Whitakers capitalized on the home’s great location by advertising it as having a “fine view overlooking Biltmore Village”.

In April of 1907, the Whitaker’s celebrated their twentieth wedding anniversary at their “elegant home “Reedcrest” near Biltmore”, which the reporter described as “a handsome country place lending admirably to large functions”. [39] The home was fully decorated for the occasion, and from the article’s description of the decorations we find that the house contained the following rooms: drawing room, back drawing room, reception hall, dining room, library, and upper hall (the hall was large enough to accommodate an orchestra “behind a bank of palms”). [40]

Perhaps the oddest story about Reedcrest occurred in 1907, while the house was being used for boarders. “An Odor Mystery- Strange Affair In A House At Biltmore”, was the startling headline. The article speaks for itself:

A strange incident occurred at the home of Mr. and Mrs. C. R. Whitaker at Biltmore, yesterday morning, and was re-enacted this morning. Yesterday morning while a young lady guest of the Whitakers was alone in the house she detected the strong odor of some drug and heard the noise like that of a spraying machine. She became frightened and ran to a neighbor’s and the county officers were notified. An investigation was made, but aside from the odor emanating from a closet in the room from which entrance may be had to the attic, no clue or solution to the affair was had. Again today the odor was detected with accompanying noise in the attic. Sheriff Hunter and a deputy were notified and another investigation made without success. The odor prevalent in the house was that of formaldehyde, a fluid which it is said, was never in the house. The whole affair is mystifying. [41]

Shortly after this “mystifying” incident, in the winter of 1907, the Whitaker’s again rented out their home and permanently moved to Hendersonville, NC, where Charles had recently purchased an “Ice and Laundry” business. Through the years of 1908-1912, Reedcrest, though leased, also operated as a boarding house. In October of 1912, the Whitaker’s finally sold their lovely home to John L. English and his wife. J. L. English, owner and president of the English Lumber Company had moved to Asheville in 1902 to establish his wholesale and retail lumber business. The English Lumber Company occupied seven acres between the Southern Railroad tracks and the French Broad River, across the tracks from the Asheville Depot.

The English family only occupied Reedcrest for two years, until September of 1914, at which time J. L. English sold his company to his brother J. M. English and business partner, Clarence Gordon, and moved to New York City to open a new lumber brokerage. [42] English and his wife Cora had sold Reedcrest to the English Lumber Company earlier in the year, [43] but then in October the Company sold the property to brothers Robert & Charles C. Greenwood. [44] On October 6th, just three days after signing the deed to the property, while the house was still unoccupied, it succumbed to a devastating fire. “There was no way in which to fight the fire”, it was reported, “and the spectacular blaze reduced the handsome building to ashes in a very short time”. [45] The property was eventually sold and subdivided into lots along Westview & Eastview Avenues off Fairview Road in modern-day Oakley.

CLARENCE & MAUDE REED MCCALL HOUSE

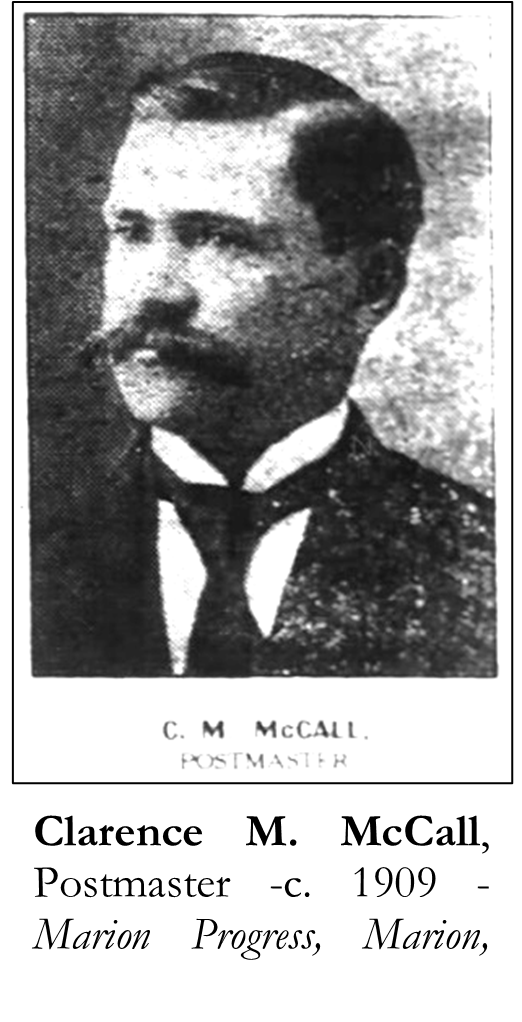

Five years after her father Thomas Jefferson Reed’s death, Lula Maude Reed married Clarence Milton McCall, of Marion, N.C., on May 6, 1908 at Biltmore, NC. [46] The couple first moved to Marion, where Clarence was serving as postmaster. In 1912 they built a house in Marion at the corner of Henderson and Logan Streets. [47] But three years later, after serving as postmaster for eight years, Clarence was replaced as postmaster by William Goodson in 1915.

The McCalls moved back to Biltmore, moving into Maude’s childhood home, the Old Reed House, where they resided with Maude’s mother Sue Reed. Prior to moving back, Clarence, along with wife and his brother-in-law Clyde Reed, had established the Biltmore Hay and Grain Company. [48] Clarence became involved in the new business as well as helping to manage the other Reed family businesses, such as the Biltmore Milling Company, reorganized from the old Biltmore Roller Mills, first established by his late father-in-law, Thomas J. Reed.

In January of 1923, it was formally announced that US President Warren G. Harding had appointed Clarence M. McCall as Postmaster for Biltmore, NC. [49] Shortly after he assumed his new position, a new Biltmore post office was built by Lloyd Jarrett on “Short Street between the Plaza and All Souls’ Church”. [50]

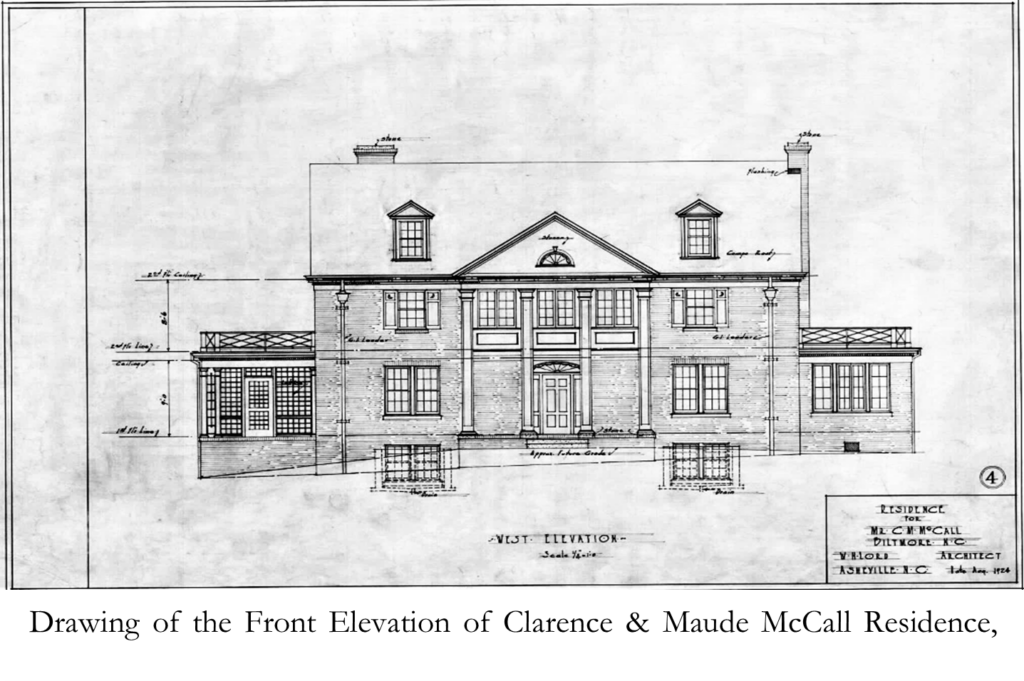

In 1924, Clarence and Maude decided to build a new home for their growing family. They chose to build on the top of the hill just above the old Reed House. They hired local architect William Henry Lord to design a two-story brick Colonial Revival home, with two-story front and rear porte-co-chere. We have 14 surviving architectural drawings for the house, including basement, first floor, and second floor plans, exterior elevations, detail drawings of front porch, ironing board, dumb waiter, medicine cabinet, and main stairway. [51] The drawings are merely dated “August 1924”, which is probably when the drawing set was completed. The first floor contained a living room, dining room, kitchen, pantry, breakfast room, powder room, and sun parlor (on the south side of the house). The second floor included four bedrooms, three bathrooms, a dressing room, and a sleeping porch over the front entrance porch.

Tragically, just as construction of their new home was beginning, Clarence suddenly died of pneumonia on August 31, 1924, after being ill for only two weeks. Maude McCall, with their adopted son, Clarence M. McCall, Jr. (adopted shortly after his birth in 1921), moved into the new home when it was completed. Sometime shortly thereafter, Maude’s mother, Sue B. Reed, moved from the old Reed House at the bottom of the hill, into the new home with her daughter. The old Reed House was then rented out, until it was destroyed by fire in 1943.

Maude and her family continued to live in their new house on the hill above the old Reed house through the 1920’s and 30’s, with Maude receiving income from her interest in her father’s estate, which leased out the estate’s land to numerous businesses, such as North State Materials, Gulf Oil, Littleford Lumber and Biltmore Coal. Maude also had an interest in the 1926 development of “Chedworth Hills”, which was developed from the T. J. Reed estate lands south of Sweeten Creek along West Chapel Road (now London Road). Maude even took in boarders during the height of the depression to generate income for the family.

In 1944, Maude sold the house and adjacent industrial property, west of the house, as well as property on the south side of Fairview Road to E. S. and Irene Koon, and moved to downtown Asheville. Two years later, the Koons sold the 13 acres “home tract”, which included the house, to Wilbur & Maybelle B. Bryson. Wilbur was a railroad engineer with the Southern Railway, and Maybelle operated a beauty salon at Battery Park Hotel in downtown Asheville. In 1957, after working for the railroad for 43 years, Wilbur Bryson suffered a fatal heart attack in his railway cab in Salisbury, NC. Maybelle continued to live in the house, along with her brother William J. Britt who had come to live with the Brysons prior to Wilbur’s death.

In 1968, William Britt passed away, and Maybelle, through her son Rodney, acting as her attorney-in-fact, sold the house and surrounding 13 acres to Irving & Evelyn K. Ness. The Ness family owned several industrial businesses and properties, including Ness Brothers which sat on the site of the old Reed House at the bottom of the hill below the McCall home.

Evelyn K. Ness was the first to attempt to have the property rezoned for a residential housing complex, the property became vacant, and remained so for the remainder of its existence. From 1968, until 2015, numerous projects with such names as “Biltmore Pointe” and “Whitaker Hill” were proposed for development of the site. Now the former site of the Clarence & Maude Reed McCall house, formerly a wooded hillside, is a leveled plateau above a massive concrete block retaining wall on its west side and is the site of a recently constructed 309 residential units (apartments)/retail complex called “The District”, at 106 Fairview Road.

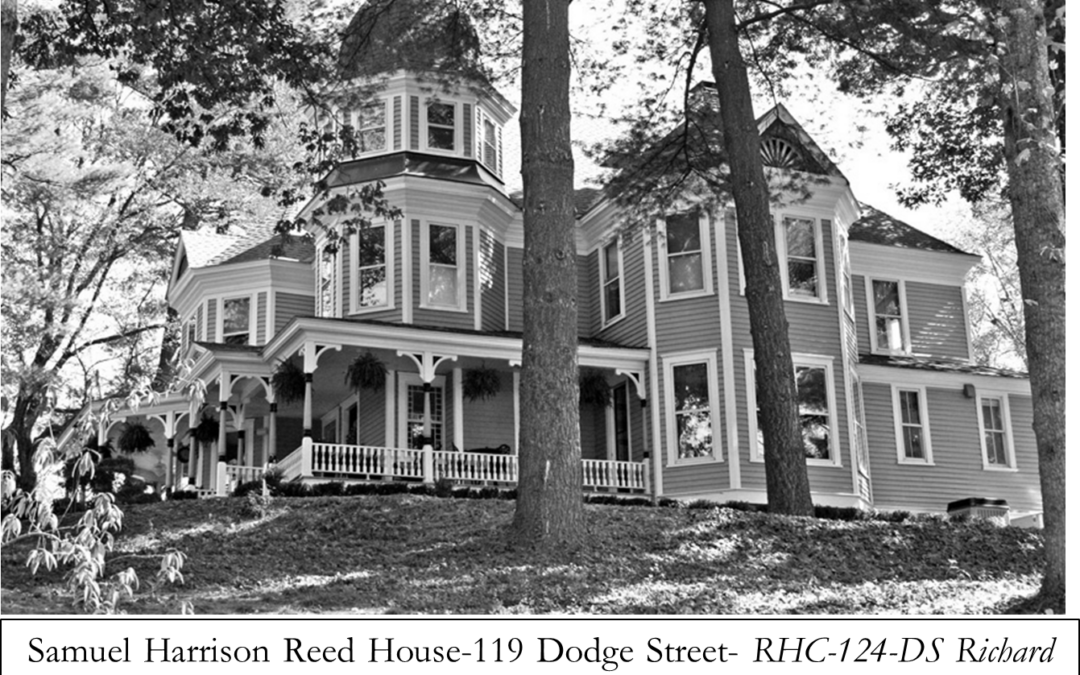

SAMUEL HARRISON REED HOUSE (REED’S HILL/BILTMORE TERRACE)

At the 1884 court ordered division of Joseph Reed’s estate at Asheville Junction (later-Biltmore Village), Joseph’s son, Samuel H. Reed was allotted the 92-acre Lot. No. 1, which bordered the Asheville-Hendersonville Road on the west. Thomas J. Reed (his brother) was allotted Lot No. 2 on the east, and the Swannanoa River on the north. At the time of his inheritance, S. H. Reed was 33 years old.

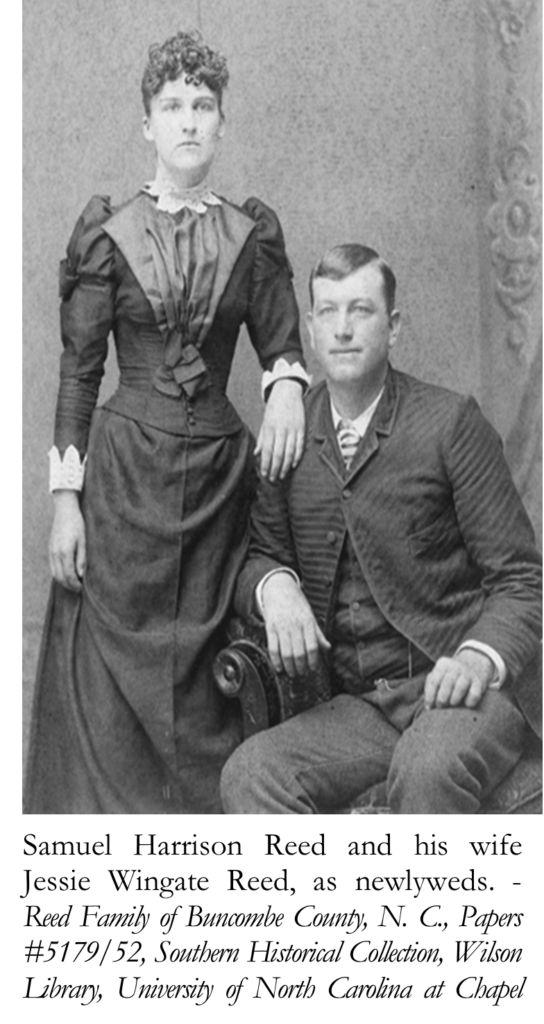

Samuel Harrison Reed was born on May 6, 1851 to Joseph and Catherine Reed, near Gash’s Creek in southeast Asheville. Samuel obtained his schooling at Col. Stephen Lee’s school in Chunns Cove, after which he studied law under the tutelage of Judge Bailey at Bailey’s school on the North Fork of the Swannanoa in Black Mountain, NC. [52] Reed was licensed to practice law by the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1872, and immediately set up his practice in an office on S. Main Street (Biltmore Avenue) above Patton & Summey’s Store. [53] Shortly thereafter, in 1873, Samuel Reed married Jessie Wingate.

In June of 1890, S. H. Reed sold 42 acres of his 92-acre Lot No. 1 to Charles McNamee, the agent for George W. Vanderbilt. [54] The 42-acre site would later become Biltmore Village. Then in 1892, in the remaining western portion of his Lot No. 1 inheritance, Samuel decided to build a new family home. At the time, 41-year-old Samuel and his wife Jessie and their three surviving children, Kate, Cora, and Maurice were living in a house on Woodfin Street near the Oaks Hotel. Infant Charles Wingate, a son, was born to Samuel and Jessie that same year, 1892— born just before the new home was completed.

In addition to his law practice, Reed also became an active local businessman, eventually owning several properties, including the Oaks Hotel on Woodfin Street in downtown Asheville. In May of 1892, no doubt in preparation of building his new country home, Reed decided to rent out two of his downtown properties. “FOR RENT”, advertised Reed, “My cottage and premises on Bailey Street known as the Burkholder cottage. Also, my store, No. 65 North Main Street, with 6 living rooms above it. Apply to S. H. Reed.” [55]

Reed’s new Queen Anne styled two-story residence was reported to cost $5,000. [56] The site of the new Reed home was on an elevated plateau overlooking what to the west would soon become the Biltmore Village. In fact, this relationship is clearly illustrated in an early photo taken in the late 1890’s as Biltmore Village was being developed. Samuel Reed’s house is shown sitting on the hill, surrounded by a few trees, just above the village. [57]

Little had been reported about the design of the house, including who the architect and/or builder might have been. Its distinctive detailing, such as its three-story turret with a bell-shaped roof, its elaborate and extensive wraparound porch with turned columns and bracketed fretwork, and its many angled bays, all suggest that it was designed by a contemporary architect familiar with the then popular and stylish high Queen Anne style of architecture. There were several local architects and builders in Asheville in 1892 who may have designed it. My suspicion (only that) as to a local architect would be narrowed down to: Arthur Wills, Allen L. Melton, E. W. Burkholder, or J. A. Tennent. Also, it could have been designed by and selected from one of the popular plan catalogs such as those published by George F. Barber or R. W. Shoppell.

Samuel and his wife Jessie only lived in their dream home for thirteen years before their deaths in 1904 and 1905. In October of 1904, S. H. Reed suffered a massive stroke, reportedly, “little hope is entertained for recovery”. [58]

Numerous modern-day occupants of the Samuel Reed house have repeatedly reported that the house has a resident ghost or ghosts! Although I am not one to believe in, or even entertain, ghost stories or “hauntings”, if ever there was a basis for such stories, I confess that the Reed house has the makings of a great one. At the time of Samuel Reed’s stroke, and before either of the couple had passed away, in November 1904, it was observed that the Reed Family (siblings and descendants of Joseph Reed) were then experiencing “an unusual number of distressing events” in the past twelve months. [59] The observer noted that a series of sad and tragic events had befallen the Reed Family within the year:

“Twelve months ago, Thos. J. Reed suffered a stroke of paralysis from which he died. Two weeks ago S. H. Reed was stricken with paralysis and is now in a critical condition while his wife is in in the last stages of a terrible affliction from which it is thought she cannot very long survive. Three days since [S. H. Reed’s stroke] one sad accident to Mr. H. A. Latham, a son-in-law of Mr. Mark L. Reed resulted in his tragic death, and yesterday death also removed Mr. L. F. Sorrells, a brother-in-law of Mr. M. L. Reed. Dr. George W. Reed, postmaster at Biltmore has been seriously ill for the past few days and his friends are anxiously watching lest he too should add another incident to this long chapter of gloomy occurrences. But this is not all for death and sickness are not the only catastrophes that can befall mankind and a few weeks ago the home of Dr. Gus Reed, which had been beautifully furnished, was burned to the ground. The mysterious origin has never been discovered”. [60]

Jessie Reed died a month later, on December 10, 1904. [61] Meanwhile, Samuel had regained the use of his limbs and appeared to be on the road to recovery. However, just six months later, on May 29, 1905, Samuel H. Reed died at his home. [62]

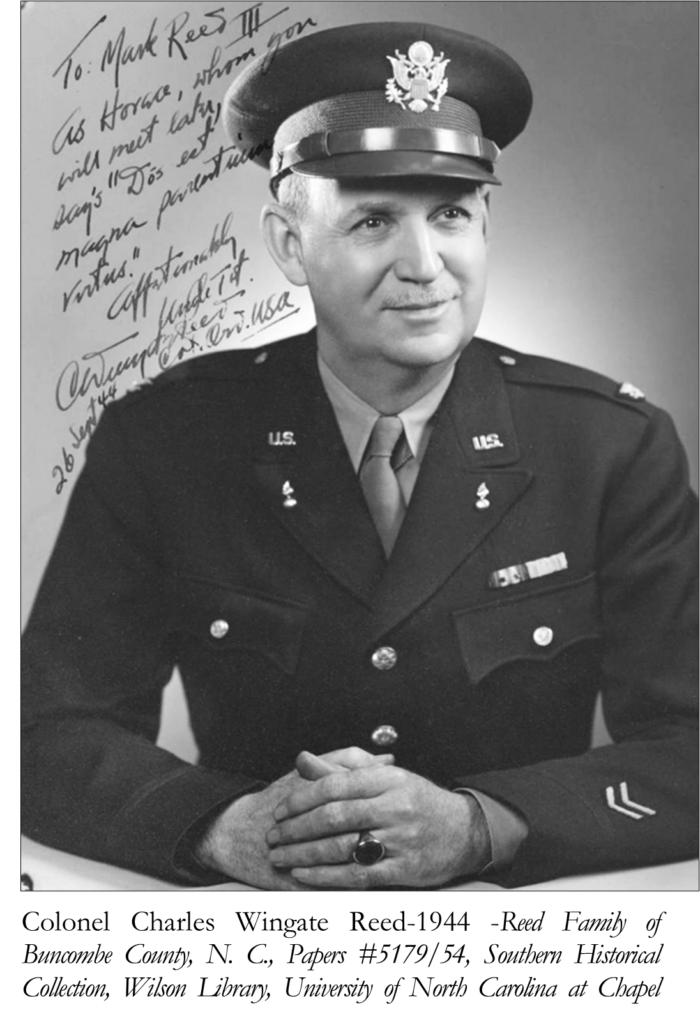

Three days before his death, Samuel Reed had his brother-in-law, C. R. Whitaker, start to advertise the house “For Rent”. [63] Oddly though, Samuel H. Reed, an attorney, died without a Will. This seemed especially odd in that he was apparently yet of enough “sound mind” three days before his death to instruct his brother-in-law to begin advertising the house for rent The family searched for a will, even going so far as to contact the manufacturer of Samuel’s safe to obtain a combination to open it. However, no will was found. It was believed that Samuel had made a will at one time, but had since “destroyed the instrument”. [64] The estate, which was valued at between $75,000 and $100,00, went into probate, with C. R. Whitaker (who was still living “next door” at Reedcrest) being appointed as the administrator. [65] As is often the case, the Court appointed commissioners to determine an equal division of the estate between the four heirs, daughters Cora Reed Logan and Bonnie Reed Heritage, and sons Maurice Reed and Charles W. Reed (both sons being minors under the guardianship of their uncle C. R. Whitaker). In the allotment the Samuel Reed house was allotted to thirteen-year-old Charles W. Reed, under his uncle’s guardianship. At that time the house was rented out, and Charles W. Reed was allotted $35 per month by his guardian “for his maintenance and support”. After high school, Charles went off to the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, where he obtained his law degree in 1912, but not before marrying Miss Anice Williams of Chapel Hill in 1911. In May of 1912, following his graduation, Charles and his wife moved back to Asheville, and into the old Samuel Reed house. However, since he was only 20 years-old, he was still under guardianship, he had to ask his guardian, Kingsland VanWinkle, to petition the court to allow VanWinkle to advance him $1,250 from his portion of his father’s estate in order to paint and make repairs to the house, including a new shingle roof, and to buy furniture and fixtures. [66]

The Reeds moved back into Biltmore Terrace (a new name for the Samuel Reed property) just in time to welcome their first child, Charles Wingate Reed, Jr. Baby Charles was born August 17, 1913 at the Samuel Reed house-both the father Charles and the house had just turned 21 years-old!

Charles W. Reed, the month before his first child was born, had purchased a half-interest in a real estate firm of Marstellar and Company in Asheville. [67] A month later, on the same day that his son was born, another announcement was made in the newspapers that Charles W. Reed would be developing his property into a subdivision called “Biltmore Forest”, and that the lots would be sold by auction on Tuesday, August 19, 1913, by the Southern Land Auction Company. [68] The auction announced that the sale included 56 lots and “1 Fine 12-room House”. [69] Apparently the auction was unsuccessful as I could find no announcement of the results and no resultant deed transfers.

Apparently, the Biltmore Terrace property/ Reed’s Hill house was then purchased from Charles W. Reed by his first cousin Clyde S. Reed and then sold in 1918 to John P. Feezor. Around 1916, Charles W. Reed and his family moved to Washington, DC, where he got a job as the Clerk and Assistant Supervisor at the Home for the Aged and Infirm at Blue Plains. [70] Ironically, although on his 1917 draft registration he had claimed an exemption “on Acct. dependent wife”, [71] by April of 1918 Reed was in the Army serving “somewhere in Italy” as an aviation cadet. [72] After the war, Reed continued a career in the Army, eventually reaching the rank of Colonel. Although Charles W. Reed returned to Asheville later in life (1940’s), he never returned to live in his childhood home.

The Samuel Reed/Reed’s Hill House eventually obtained the address of 119 Dodge Street, and continued to serve as a family home for many years. But by 1973, when Marge Turcot purchased the house, it had been turned into apartments and was in need of restoration. The Turcot family began the slow restoration of the house. In 1974, while still actively refurbishing the house, Marge Turcot’s children, Mike (age 19), and Susan (17) and two partners, Steve Smith (age 18) and Peter Martin (age 21), formed their own company called Counter-Culture Contracting. The goal of the company was to inspire and train other do-it-yourselfers how to do “painting, papering, plastering, carpentry, insulating, minor repairs, and remodeling jobs” for homeowners. [73] The Turcots subsequently opened the house as the Reed House Bed & Breakfast. After years of painstaking restoration by Turcot and her family, in 1988, the under the orchestration of Turcot, then President of the Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County (which had formed in 1976), the “Samuel Harrison Reed House” was designated, by the Asheville City Council as an official “local historic landmark”. [74]

The Samuel Reed house remains today and is still operated as a Bed & Breakfast inn, now called the “Biltmore Village Inn”. Besides being designated a local historic landmark, the house is also on the National Register of Historic Places.

CLYDE S. REED HOUSE

The last Reed family house to be built on the Reed lands, though built after Biltmore Village was established, was the Clyde S. Reed house. At the death of Thomas Jefferson Reed, his property, Lot No. 2 from his father Joseph Reed’s estate, was divided in half, with his daughter Lula Maude Reed McCall getting the northern half, surrounding the old Joseph Reed house, and his son Clyde S. Reed getting the southern half, below and along Sweeten Creek.

Clyde Sidney Reed was born in the old Joseph Reed house on August 1, 1883, to Thomas Jeferson Reed and his wife Susan Ashworth Reed. In 1900, at the age of seventeen, Clyde enrolled at the Wake Forest College, in Wake Forest, NC. He attended for two winter sessions, studying English, Latin, and Mathematics, before returning home to Asheville in May of 1900. [75]

Clyde Reed, upon his return home, took over the management of the two family businesses, the Swannanoa Ice and Coal Company and the Biltmore Roller Mills, both of which were located just outside of Biltmore Village.

In 1906, Reed was elected Buncombe County Tax Collector. Later that same year, Clyde Reed married Miss Lucy Dowtin of Bryson City, NC. [76] The newlyweds moved into the old Joseph Reed house, where Clyde had been living with his mother Sue Reed.

By 1910, Clyde was an active businessman having interests in numerous businesses. Besides the two family businesses, he was the manager of the Asheville Dray, Fuel, and Construction Company, and was a partner with Horace Wells in the road construction company of Reed & Wells. In 1914, Reed & Wells dissolved their partnership, with each partner forming their own contracting businesses. Also in 1910, Clyde Reed, in partnership with J. T. Roberts, and Kingsland VanWinkle, formed the Biltmore Development Company. It was to this company that Charles W. Reed sold his property (the Samuel Reed House) to be developed into Biltmore Terrace.

Following the dissolution of Reed & Wells, in 1918, Clyde Reed, along with Porter A. Webb and Hugh M. McDowell, formed the Asheville Construction Company. The new company was authorized to deal in all kinds of construction, buildings, roads and bridges, and also deal in quarrying, crushing, and selling stone. [77]

Finally, in 1925, Clyde Reed decided to build his own home on his inherited property in Biltmore. He hired Scottish-born architect, S. Grant Alexander, to design a two-story stone house. Reed chose to build his modern home on a hill between London Road and Sweeten Creek Road, which was part of his inheritance of the Joseph Reed’s lands.

Unfortunately, the Reeds were only living in their new home for five years before the 1929 economic crash. Of course, having numerous businesses and dealing in various development and construction projects, Reed was highly effected by the economic downturn. Perhaps his biggest loss was as one of the directors of the Biltmore-Oteen Bank, when it failed and all the directors were indicted. Though costly, Clyde Reed and the other directors were exonerated from criminal charges in 1931, but in return were required to pay back a share of funds to ad in the final liquidation of the bank. [78] A month or so later, Clyde Reed’s wife, Lucy Reed died of a heart attack on August 3, 1931. [79]

Clyde Sidney Reed died on August 18, 1939. In February of 1939, just before his death, his sister Maude Reed McCall who had purchased the house and property out of foreclosure, sold the Clyde Reed home and property to the Asheville Orthopedic Home. [80] The home still remains as the centerpiece of Carepartners, the successors to the Asheville Orthopedic Homes.

NOTES

[1] 07/17/1790 William Davidson & James Davidson to William Forster, Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Deed Bk. 1-A page 75.

[2] Foster A. Sondley, Asheville & Buncombe County- Vol. 2, (Asheville, NC: The Advocate Printing Company, 1930), p. 758.

[3] Ibid.

[4] 07/20/1802 William Forster, Sr. to Thomas Forster, Jr., Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Deed Bk. 8 page 157.

[5] Reworded from description of Foster A. Sondley, Asheville And Buncombe County, (Asheville, NC: Inland Press, 1922), page 118.

[6] Annual Report of the Board of Public Improvements of North Carolina to the General Assembly- December 10, 1822, Together with Mr. Fulton’s Report to the Board on the Public Works projected and carrying on throughout the State during the present year. (Raleigh, NC: J. Gales & Sons, 1822), page 66.

[7] Western Carolinian, Salisbury, NC- April 13, 18

[8] Charlotte Journal, Charlotte NC- January 18, 1839, page 3.

[9] From an advertisement for Foster’s estate in 1859- Asheville News, Asheville, NC, February 10, 1859.

[10] Grady L. E. Carroll, Francis Asbury in North Carolina; the North Carolina portions of the Journal of Francis Asbury. Vols. I and II of Clark ed., (Nashville, TN: Parthenon Press), page 176.

[11] Ibid., page 170.

[12] Sondley, A History of Buncombe County- Vol. 2, page 760.

[13] “State Troops and Volunteers”- March 29, 2015 Post on Facebook.

[14] John W. Woodfin Est– Nicholas W Woodfin, Exec to Samuel Whedbee, Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Deed Bk. 29 page 23.

[15] 12/06/1871 J. G. & Annie Hardy to Joseph & Catherine Reed, Main Street, Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Deed Bk. 34, page 368.

[16] 12/26/1872 James S. Whedbee; Admin. -Samuel Whedbee to Joseph Reed, Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Deed Bk 37, page 132.

[17] “Best, Swannanoa Bridge, Biltmore or Foster Place”, by C. Bruce Whitaker, Fairview Town Crier, August 3, 2017- https://fairviewtowncrier.com/2017/08/best-swannanoa-bridge-biltmore-or-foster-place/

[18] Catherine W. Bishir, et. al. Architects and Builders in North Carolina: A History of the Practice of Building. (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1990) p.142.

[19] http://www.historync.org/railroad-WNCRR.htm

[20] Ibid

[21] Information from: Cary Franklin Poole, A History of Railroading in Western North Carolina. (Johnson City, TN: The Overmountain Press, 1995), pages 2-5.

[22] “Work on the W. N. C. Railroad”, Asheville Weekly Citizen, October 16, 1879.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] “Iron Arrived”, Asheville Weekly Citizen, September 30, 1880.- “…the work of laying the track to Swannanoa Bridge commenced Monday, with a double force of hands working day and night, and the track will doubtless be completed to the bridge by Saturday night.”

[26] The Semi-Weekly Citizen, Asheville, NC, April 15, 1880.

[27] The Weekly State Journal, April 13, 1880, Raleigh, NC.

[28] The Semi-Weekly Citizen, Asheville, NC, April 15, 1880

[29] J. P. Davison, The Asheville City Directory and Gazetteer of Buncombe County for 1883-’84 (Richmond, VA: Baughman Brothers, Printers, 1883), page 75.

[30] Proceedings recorded in the “Special Proceedings” book 4, page 104- Buncombe County Superior Court, and Book 70, pp. 105-145, Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Asheville, NC.

[31] Survey now the property of the Biltmore Estate-“Joseph Reed’s Foster Farm, Drawings Collection, BHA00215, Biltmore Estate Archives, Asheville, NC.

[32] “Ice, Ice, Ice”, advertisement, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 22, 1887, p. 4.

[33] Asheville Weekly Citizen, Asheville, NC, March 27, 1890, page 1.

[34] Asheville Citizen Times, Asheville, NC, July 17, 1943.

[35] “Ice Plant Sold”, French Broad Hustler, Hendersonville, NC April 15, 1907, page 2.

[36] Asheville Citizen Times, Asheville, NC July 1, 1895.

[37] Asheville Citizen Times, Asheville, NC October 20, 1897.

[38] Asheville Daily Gazette, Asheville, NC August 26, 1900.

[39] Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, NC April 14, 1907, page 11.

[40] Ibid.

[41] “An Odor Mystery- Strange Affair In A House At Biltmore”, News and Observer, Raleigh, NC, October 22, 1907, page 1.

[42] Asheville Gazette-News, Asheville, NC September 23, 1914.

[43] J. L. & Cora English to English Lumber Company, (Hickory Nut Gap Road) Deed Book 191, page 64, 03/24/1914- Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Asheville, NC.

[44] English Lumber Company to Robert Greenwood & C. C. Greenwood, (near Biltmore) Deed Book 183, page 533, October 3, 1914- Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Asheville, NC.

[45] “$10,000 Fire at Asheville”, The Chronicle, Albemarle, NC, October 12, 1914.

[46] “McColl-Reed at Biltmore”, Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, NC May 7, 1908, page 7.

[47] “McDowell”, The News-Herald, Morganton, NC, June 6, 1912, page 1.

[48] Durham Morning Herald, Durham, NC, May 15, 1915, page 5.

[49] “Nominate McCall As Biltmore Postmaster”, Asheville Citizen Times, Asheville, NC, January 29, 1923, page 5.

[50] “Biltmore To Have Modern Post office”, Asheville Citizen Times, Asheville, NC, July 15, 1923, page 12.

[51] SA1061, William Henry Lord, architect-RESIDENCE FOR MR. C. M. McCALL- 14 drawings, North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

[52] “Memorials”, Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the North Carolina Bar Association, Volume 7 , North Carolina Bar Association, The Association, 1905 – Bar associations, p. 110.

[53] See advertisement: Weekly Pioneer, Asheville, NC, May 30, 1872, p. 4.

[54] 07/02/1890 Samuel H. & Jessie W. Reed to George W. Vanderbilt 42 ACRES HICKORY NUT GAP ROAD Db. 71/393. Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[55] Asheville Citizen-Times, May 10, 1892, p. 4.

[56] Asheville Citizen-Times, July 7, 1892, p. 4.

[57] Job #170, No. 11 George W. Vanderbilt, Asheville, NC (Historic Negative Collection), Olmsted Archives, Frederick Law Olmsted NHS, NPS- https://www.flickr.com/photos/olmsted_archives/

[58] Asheville Citizen-Times, October 25, 1904, p. 8.

[59] REED FAMILY’S SAD AFFLICTIONS- AN UNUSUAL NUMBER OF DISTRESSING EVENTS DURING TWELVE MONTHS”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 8, 1904, p. 2.

[60] Ibid.

[61] “Mrs. S. H. Reed Passed Away at Biltmore Yesterday Noon”, Asheville Citizen-Times, December 11, 1904, p. 8.

[62] Asheville Gazette-News, May 30, 1905, p. 5.

[63] Asheville Gazette-News, May 26, 1905, p. 6. – The advertisement noted that along with the house came also a vineyard, garden and orchard.

[64] “Wealthy Asheville Citizen Left No Will”, The Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, NC, June 22, 1905, p. 2.

[65] Ibid.

[66] “In Re-Petition of Kingsland VanWinkle, Guardian C. W. Reed”, To the Superior Court of Buncombe County, May 13, 1912.-Wills and Estate Papers (Buncombe County), 1663-1978; Author: North Carolina. Division of Archives and History (Raleigh, North Carolina); Probate Place: Buncombe, North Carolina –ancestry.com

[67] “CHANGE IS MADE IN REAL ESTATE FIRM”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 1, 1913, p. 2.

[68] “SALE PROMISES TO BE VERY SUCCESSFUL”, Asheville Citizen-Times, August 17, 1913, p. 8.

[69] Asheville Citizen-Times, August 18, 1913, p. 8.

[70] See U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 for Charles Wingate Reed, District of Columbia, Washington City, Precinct 11-June 5, 1917.- ancestry.com

[71] Ibid.

[72] “ASHEVILLE AVIATOR WRITES NEWSY LETTER”, Asheville Citizen-Times, April 8, 1918, p. 8.

[73] Asheville Times, March 29, 1974, p. 1.

[74] Asheville Citizen-Times, December 21, 1988, p. 17.

[75] Asheville Citizen-Times, May 28, 1900, p. 8.; and See: Wake Forest College. (19061967). Bulletin of Wake Forest College. Catalog of Students (Wake Forest, N.C.: Wake Forest College), 1900) p. 15.

[76] Asheville Citizen-Times, September 27, 1907, p. 17.

[77] 12/30/1918 ASHEVILLE CONSTRUCTION CO. [INC ] Db. C004, p. 564. -Buncombe County register of Deeds.

[78] “Officers Closed Banks Pay Over $200,00; Hood Drops Charges”, Goldsboro News-Argus, Goldsboro, NC, July 1, 1931.

[79] “Mrs. C. S. Reed Funeral Today”, Asheville Citizen-Times, August 4, 1931, p. 8.

[80] 02/04/1939 Maude Reed McCall to Asheville Orthopedic Homes, Inc. WEST CHAPEL ROAD Db. 514, p. 367- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.