By Dale Wayne Slusser

Many Asheville residents, like me, have passed this street sign at the intersection of White Pine and Brackettown Roads at the north entrance to Asheville Mall, and asked the question- “Where is Brackettown”? This is especially perplexing because this “Brackettown Road” merely and ONLY leads into the mall. A study of old newspaper articles, deed descriptions, old plats and maps, old documents and old photos reveals the answer! And the answer not only leads us to Brackettown, but also to Ben Ragsdale’s brick house in the heart of Brackettown.

I had discovered the existence of Brackettown Road before I noticed the street sign. A few years back, while researching for a yet to be written book about the “forgotten” houses along the Swannanoa River corridor, I discovered a description of this area during the 1890’s, in the recollections of “Aunt Grits”, Margaret Davis Goodale, who had grown up on the farm in this area. Margaret’s father, Edwin Paschal Davis moved his family to Asheville in 1884 and purchased the Dr. John B. Weaver farm of 192 acres, which included the area now occupied by Kenilworth Lake, Kenilworth Forest, the Asheville Mall and part of the Kenilworth neighborhood to the west. Margaret was born in 1885 on this farm, shortly after the family had arrived.

“Aunt Grits” in her recollections gives us a good description of this area- (I have added modern geographical names in brackets):

“The house where I was born was about 3 miles from Asheville, N. C. and a little over a mile from the small town of Biltmore where we went for mail, ice and a few items of food and household supplies. Biltmore was also a train stop where we met passengers and picked up freight packages. Leaving Biltmore to get to our house we would cross the Swannanoa River on a high iron bridge (recently built to replace one washed away by a flood) then turn east following up the river on a fairly good (depending on the season of the year) dirt road [Swannanoa River Road] for about a mile, passing one house [“Azalea”-Trescott House]. A narrower road [Patton Farm Road] turned off [to the left], leading through a field, crossing a brook [Ross Creek], and plunging into a dark, wild beautiful glen where the brook rushed over rocks, and rhododendrons grew thick and lush, — then out, — and there was our house! The family named it “Tanglewild” on account of the rhododendron thicket.

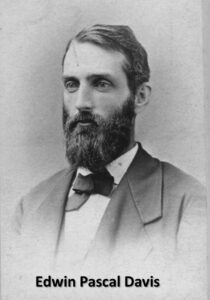

Beyond the house a lovely valley [Ross Creek Valley] widened out toward the north, nearly a mile long to the east of this were low hills and to the west a mountain ridge – “Beaumont” – (“Beaucatcher” to many of the local people) – beyond which was Asheville. The brook [Ross Creek], which flowed along the western edge of the meadow, came down from the hills far to the north [Town Mountain at Chunns Cove] and was normally a delight, but thunderstorms occasionally cooked up a “freshet” and the brook would become a roaring torrent, even overflowing the meadow to the detriment of some of my father’s best crops. The road [Patton Farm Road] crossed the brook close to our house. Through a “ford” for horses and carts, with a foot-bridge for pedestrians, then skirted the east side of the meadow, ambled up a hill where our second house [named Crowhurst] was later built and finally joined another road [Beaucatcher Road]which climbed over Beaumont to Asheville.”[1]

Apparently “Aunt Grits” didn’t remember Brackettown Road, which started at the top of the hill where their road, later called Patton Farm Road, met Beaucatcher Road, which is now the intersection of White Pine and Tunnel Road. Perhaps Brackettown Road was even then not an oft-used road-path. Both roads were unpaved dirt roads. And actually, the northern part of “their road” up to Crowhurst was the eastern section of Brackettown Road. The earliest map that I have found which shows these two roads crossing the Davises’ Tanglewild property is the U. S. Geological Survey Topographical map of 1901. Both roads, as well as Tanglewild and Crowhurst, though unlabeled, show on the 1901 map.

For another written description of Brackettown Road (also often called Ross Creek Road), I’ve found a description by a noted local 1930’s historian:

“For many years the road from upper Swannanoa country came across Christian Creek and across the Swannanoa River at Gudger’s Ford and then by the present Oteen and along the ridge north of the Swannanoa River through the Beverly Hills property and on that ridge and down it, crossing the Haw Creek near the Haw Creek public school building and on to Joyce store where it turned to the west and crossed Ross’s Creek where Kenilworth Lake is now and on through Fountainbleau and Brackettown to the entrance of Kenilworth Road into Biltmore Avenue…”.[2]

This is a translated description for modern readers:

“For many years the road from upper Swannanoa country [Swannanoa and Black Mountain] came across Christian Creek and across the Swannanoa River at Gudger’s Ford [concrete bridge on Tunnel Road just before Riverknoll Drive] and then by the present Oteen [VA Hospital] and along the ridge north of the Swannanoa River through the Beverly Hills property [approximately following Tunnel Road- US 70] and on that ridge and down it, crossing the Haw Creek near the Haw Creek public school building [intersection at Tunnel Rd. and S. Tunnel Rd.-above Asheville Mall] and on to Joyce store [southeast corner of White Pine Drive-at “Cookout” restaurant] where it turned to the west (at the start of White Drive] and crossed Ross’s Creek where Kenilworth Lake [and Kenilworth Forest] is now and on through Fontainbleau [across Normandy Road & Duke Street off of Kenilworth Rd.] and Brackettown [starting on the east at Applegate Lane and crossing the middle of South Asheville to Thurland Avenue] to the entrance of Kenilworth Road [Forest Hill Drive] into Biltmore Avenue.

As the main section of Brackettown Road went right through the middle of the E. P. Davis property, the fate of the road was dependent on the fate of the Davis property. As eluded to in “Aunt Grits’” recollections, the Davis property was split in two in 1889, when Davis built a new family home, named “Crowhurst”, up on the hill northeast of Tanglewild. At that time Davis sold Tanglewild and surrounding 70 acres of the original 192-acre farm to Charles Benedict.[3] In 1900, Benedict sold the Tanglewild farm to what would be its last owners, Erwin W. Patton, and his wife Ellen.[4] Meanwhile, the Davis family moved to their new home on the hill (now the site of the Asheville Mall), where they lived until E. P. Davis’s death in 1908. In 1910, the Davis heirs sold the 125-acre “Crowhurst” property to Dr. Henry H. Briggs.[5] Dr. Briggs was a successful Ear, Nose, and Throat Specialist who had his residence and practice on Haywood Street (this site later became the George Vanderbilt Hotel in 1926 and is now a senior-citizens apartment building). Dr. Briggs bought “Crowhurst” as his country residence.

The demise of Brackettown Road started in 1916, when Erwin Patton decided to sell a portion of his land (46 acres) to the Happy Valley Company.[6] In 1916, in conjunction with the rebuilding of the Kenilworth Inn (the original Inn had been destroyed by fire in 1910), a syndicate of Asheville businessmen, formed the Happy Valley Company for the purpose of building the Happy Valley Country Club. The rebuilding of the Kenilworth Inn and the redevelopment of the mostly failed original 1896 Kenilworth Park subdivision, had begun in 1912, through the efforts of Jake M. Chiles, a tireless Asheville “booster” who had interested outside investor B. C. McVey “and his associates” to form the Kenilworth Development Company. The Kenilworth Development Company bought out the interests of the “old companies”, the Kenilworth Land Company and the Kenilworth Company.[7]

In the Spring of 1917, a few months after Dr. Briggs sold his portion of the Patton farm property to the Happy Valley Company, the Pattons sold the remainder of the Patton farm (Tanglewild) to Paul Roebling for $12,000.[8] It was unclear what Roebling was planning to do with his new property, whether he was planning a new residential park or an extension to the golf course?

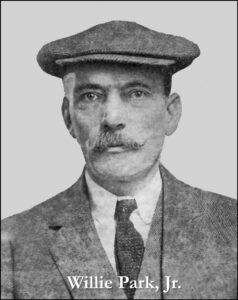

Among the officers, and prime motivators, of the Happy Valley Company, were Kenilworth developers, Jake M. Chiles, E. G. Hester and R. A. Wilson.[9] The Happy Valley Country Club was organized a few months later[10], to build an eighteen-hole golf club, to be built on the former Davis/Patton property. The new golf course, which was to include two small lakes, was designed by Willie Park, of New York, who was at that time, “one of the most noted golf course architects in the world”.[11] Willie Park, Jr. was born in Musselburgh (near Edinburgh) Scotland, to noted golfer Willie Park, Sr. Willie Park, Jr. originally made his name as a Scottish professional golfer, winning the Open championship in 1887 and again in 1889. As professional golfing at the time was not a lucrative business, Park also joined the family business, manufacturing golf clubs and balls. In 1896, Park published The Game of Golf, the first book ever written by a golf professional. However, Willie Park, Jr. would become a world-famous golf-course designer, who by the time of his death in 1925 had designed close to two hundred golf courses in the United Kingdom, Europe and North America. Park was near the end of his career when he designed the Happy Valley Golf Course.

Despite all the hype, and despite having the golf course designed and grading begun, the start of the Great War in 1917 caused the development of both Happy Valley Country Club and the new Kenilworth Inn to flounder. Fortunately for the Kenilworth Inn, the government stepped in and purchased the nearly completed Inn as a soldier’s hospital. However, work on the golf course had stalled. And even despite a 1918 plea by concerned individuals for the raising, through public subscription, of the $5,000 needed to finish the golf course for the use of the “officers, doctors, nurses, and patients of the hospital”[12], the Happy Valley Country Club, failed to become a reality. In late 1918, at a foreclosure sale by the Wachovia Bank, against a deed of trust secured originally by the Happy Valley Company in 1916, Dr. H. H. Briggs, in an effort to get back his investment, bought back his portion of the Davis/Patton property which he had originally sold to the Happy Valley Company in 1916.[13] In 1919, at an additional foreclosure sale, Dr. Briggs also bought the property that Erwin Patton had initially sold to the Happy Valley Company in 1916.[14] This gave Dr. Briggs ownership of all the lands of the failed Happy Valley Country Club.

Although the Happy Valley Country Club seemed to be the final threat to Brackettown Road, the road’s final demise was soon to follow. In March of 1923, a small article appeared in the Asheville Times, announcing the following:

“Consideration is being given to a plan for constructing a lake in Chunn’s cove, on the property of Dr. H. H. Briggs and the Kenilworth Development company, in the south end of the valley, it was learned today. The proposed lake would cover about 40 acres of land and include construction of a dam…”.[15]

In conjunction with the development of the lake, and to add to the final demise of Brackettown Road, the Kenilworth Realty Company also began an expansion of the Kenilworth Park subdivision, to the northeast of Chiles Avenue, on a 40-acre tract of the former Erwin Patton farm. This expansion included an extension of Lakewood Drive, and the current streets of Waverly Road, Sheridan Road, Plymouth Circle, and Duke Street (these streets were first called, Essewan Street, Beverly Road, Arlington Circle, and Duke Street). Construction of the new “Kenilworth Lake” did not begin until the Fall of 1924. In August 1924, the Kenilworth Development Company, in advertising for their new lakeshore development, announced that: “The conversion of “Happy Valley” into a shining lake of crystal water will begin in the next two or three weeks-actual work on the dam will start sometime in early September.”[16]

By the start of 1926, the dam had been completed and the lake was just about filled. In February of 1926, Dr. H. H. Briggs, along with E. E. Reed, and Ruffner Campbell, formed the Kenilworth Lake Company.[17] Although their charter seemed to indicate that they were a real estate company, and although they purchased the lake and surrounding acres, including the 35 acres on the east side of the lake, the company did little development except to maintain and mange Kenilworth Lake. In fact, by the time of Dr. Briggs’ death in 1931, he had bought out his two partners, and the Kenilworth Lake Company and its property became part of his estate. Excepting the actual lake, the property was not developed until 1944, when a group of Asheville men formed a new company called, Kenilworth Properties, Inc. which purchased the lake and property from the Briggs estate. Kenilworth Properties subdivided the property on the east side of the lake and built “Kenilworth Forest”, which was developed along a new street called White Pine, which is accessed only from Tunnel Road, at the eastern end of the old Brackettown Road. Brackettown Road was forever cut off, and in fact the remaining portion of road, labeled as Brackettown Road, was actually originally the driveway into “Crowhurst” from the old Brackettown Road. “Crowhurst” was eventually demolished in the early 1980’s when the property was sold to the developers of the Asheville Mall.

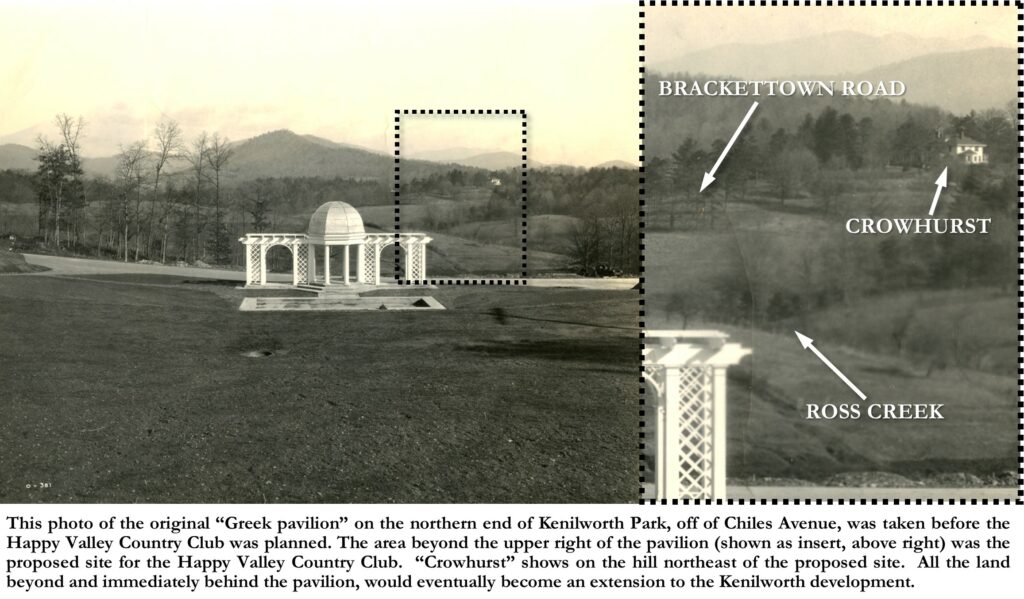

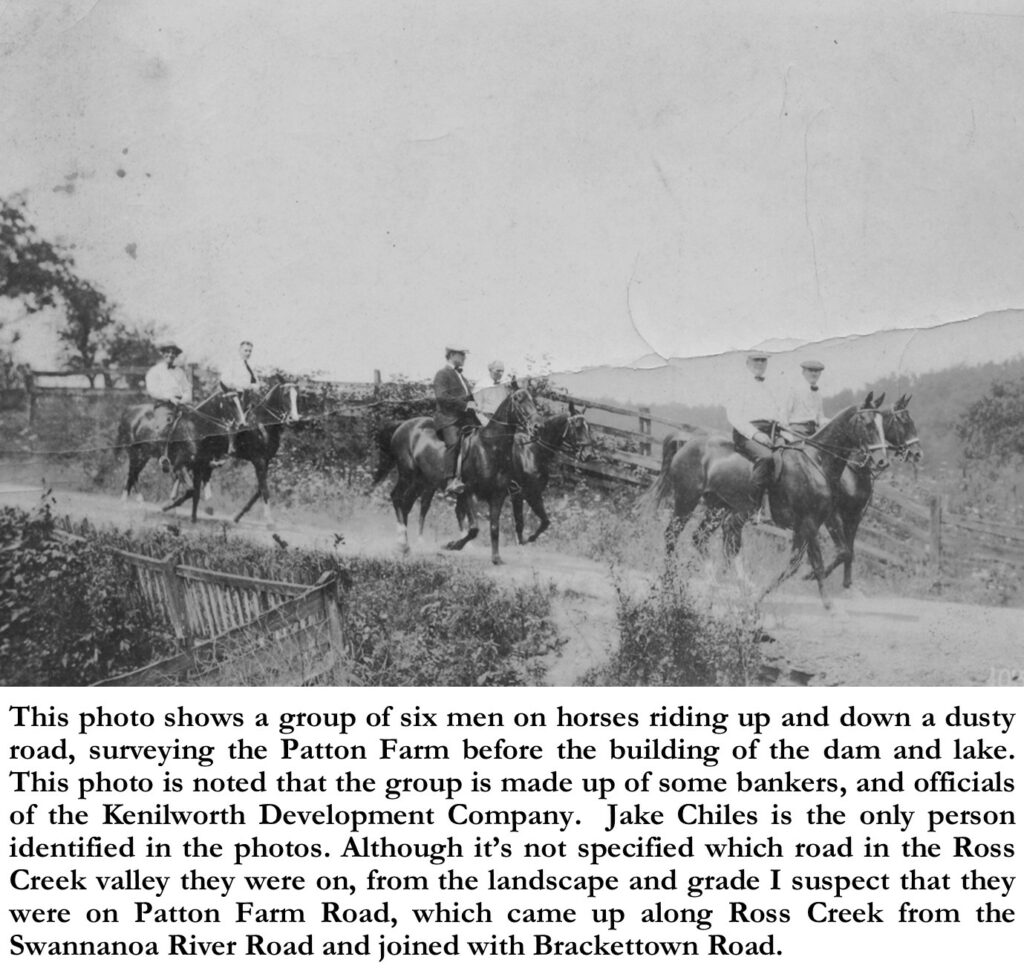

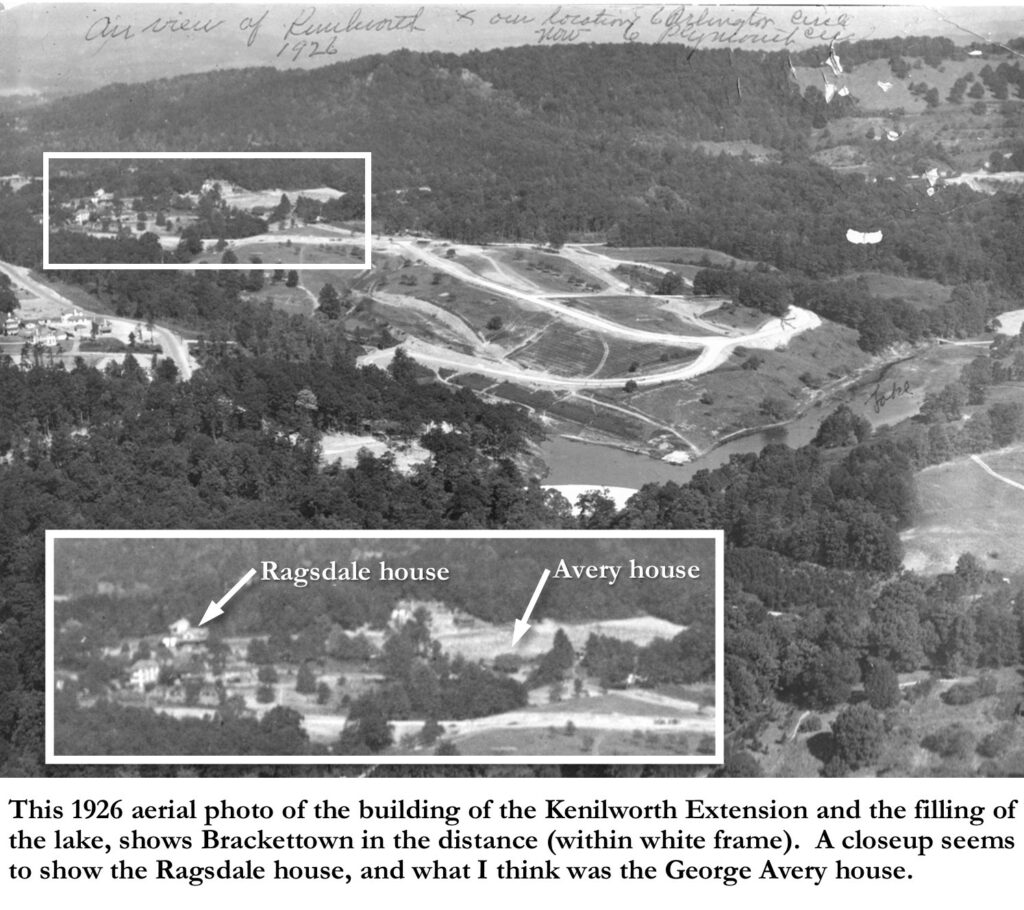

It is from this period (1924-1926), during the building of Kenilworth Lake and the Kenilworth Park extension, that we have any photos that show Brackettown Road. Because construction of the lake and the Kenilworth Park extension had already begun, we only see remnants of the former road. These photos come from the Chiles family scrapbook[18], which chronicled (though only sporadically) the building of the lake and the residential extension. The first two photos[19] show a group of six men on horses riding up and down a dusty road, surveying the Patton Farm before the building of the dam and lake. The photos are noted that the group is made up of some bankers, and officials of the Kenilworth Development Company. Jake Chiles is the only person identified in the photos. Although it’s not specified which road in the Ross Creek valley they were on, from the landscape and grade I suspect that they were on Patton Farm Road, which came up along Ross Creek from the Swannanoa River Road and joined with Brackettown Road further north. Both roads, as seen in this photo, were fairly wide and graded, but unpaved.

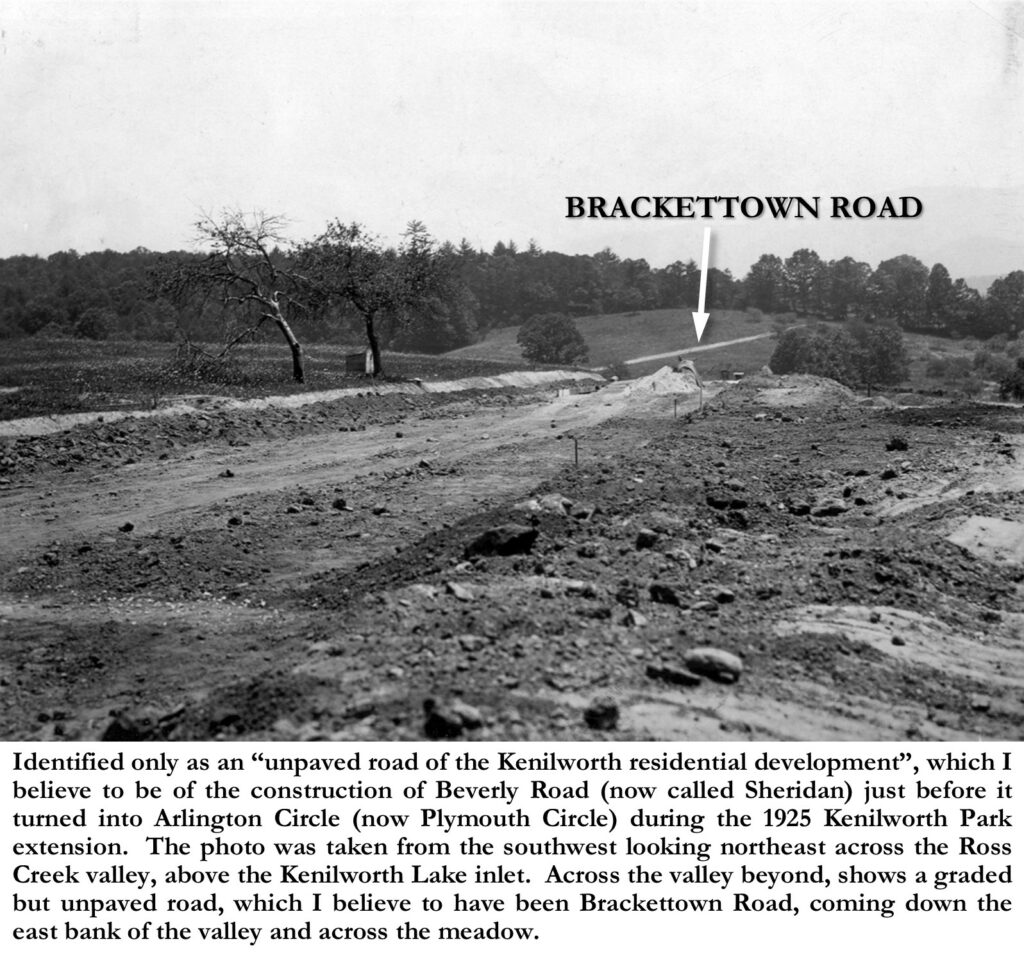

The one photo that most clearly shows a portion of the old Brackettown Road, is from the same collection of photos showing the building of the lake and the residential extension. Identified only as an “unpaved road of the Kenilworth residential development”[20], from comparison with other contemporary photos, I believe the photo to be of the construction of Beverly Road (now called Sheridan) just before it turned into Arlington Circle (now Plymouth Circle) during the 1925 Kenilworth Park extension. The photo was taken from the southwest looking northeast across the Ross Creek valley, above the Kenilworth Lake inlet. Across the valley beyond, shows a graded but unpaved road, which I believe to have been Brackettown Road, coming down the east bank of the valley and across the meadow. Because of the perspective of the photo, from atop a bluff, what doesn’t show is that Brackettown Road continued west up the west valley bank and across the then yet undeveloped Kenilworth Park neighborhood of Fountainbleau, just north of this phase of Kenilworth Park.

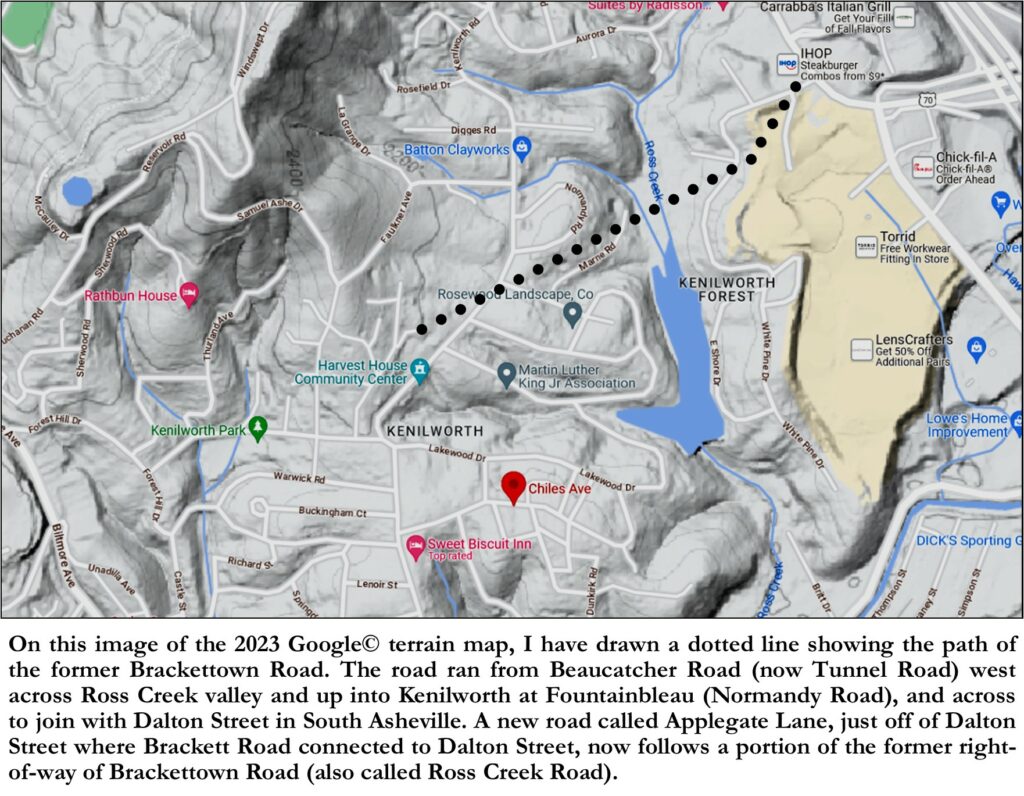

On an image of the 2023 Google©terrain map of Asheville, I have drawn a dotted line showing the path of the former Brackettown Road. The road ran from Beaucatcher Road (now Tunnel Road) west across Ross Creek valley and up into Kenilworth at Fountainbleau (Normandy Road), and across to join with Dalton Street in South Asheville. A new road called Applegate Lane, just off of Dalton Street where Brackett Road connected to Dalton Street, now follows a portion of the former right-of-way of Brackettown Road (also called Ross Creek Road).

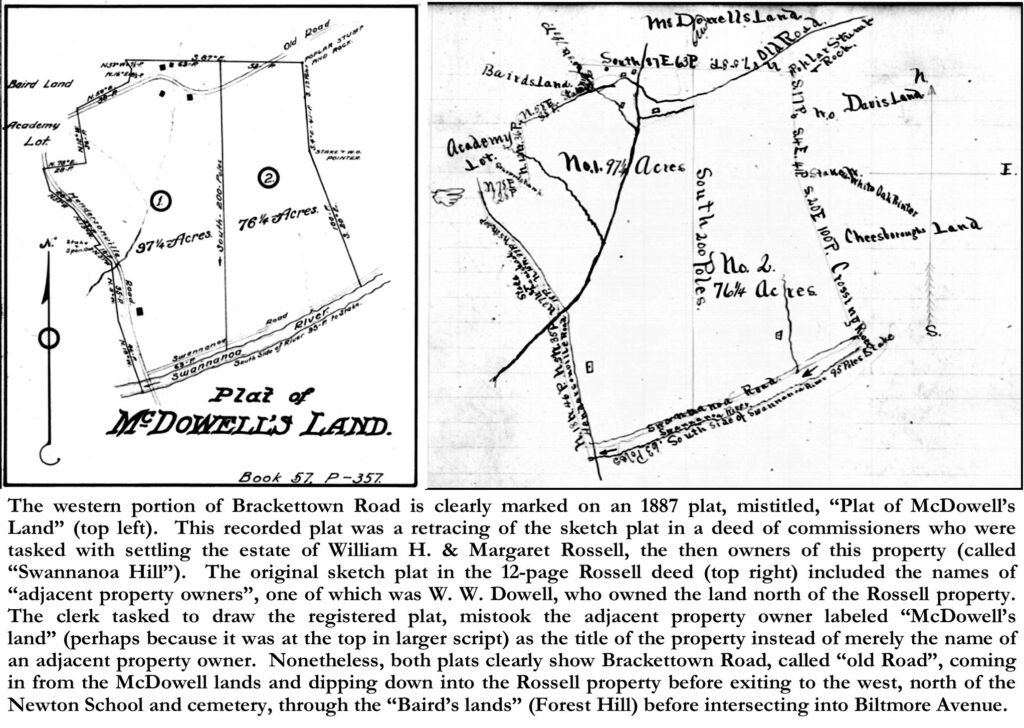

The western portion of Brackettown Road is clearly marked on an 1887 plat, mistitled, “Plat of McDowell’s Land”.[21] This recorded plat was a retracing of the sketch plat in a deed of commissioners[22] who were tasked with settling the estate of William H. & Margaret Rossell (W. H. passed away in 1885 and Margaret in 1886), who were the owners of the property which would later become Kenilworth and part of Brackettown. The original sketch plat in the 12-page Rossell deed included the names of “adjacent property owners”, one of which was W. W. Dowell, who owned the land north of the Rossell property. The clerk tasked to draw the registered plat, mistook the adjacent property owner labeled “McDowell’s land” (perhaps because it was at the top in larger script) as the title of the property instead of merely the name of an adjacent property owner. Nonetheless, both plats clearly show Brackettown Road, called “old Road”, coming in from the McDowell lands and dipping down into the Rossell property before exiting to the west, north of the Newton School and cemetery, through the “Baird’s lands” (Forest Hill) before intersecting into Biltmore Avenue. Both plats also show structures on each side of the “old road”. The structures and most of the lands north of the road on the Rossell lands, had already been sold off to Brackettown residents, such as Thomas Randall and Ferdinand Neighbors (Nachbar), although their deeds of property were recorded later as ipso facto.

So, we know that Brackettown Road stretched from Beaucatcher Road (Tunnel Road) west to Biltmore Avenue, and assuming that the road was named for “Brackettown”, it begs the question, “Where was Brackettown?” Brackettown, which was also sometimes called Clayton Hill or Claytontown, was at the time, an African American community within Kenilworth Park (as it was bordered by Kenilworth Park on three sides). The boundaries, though unofficial, roughly were: Brackettown Road (Wyoming Road) on the south, Forest Hill Road on the west, Kenilworth Road on the east (although that section of Kenilworth Road did not exist until 1926), and what is now Beaucatcher Heights on the north (although a few of the original tracts from Brackettown encroach into the new Beaucatcher Heights). So, then the next question that begs an answer is, “How did Brackettown form and develop into a community?”

Asheville had several African American communities that developed after the Civil War during the decades of legalized segregation (which sadly and shamefully lasted for almost a century). Most, if not all, of these communities, in Asheville, centered around and on land that had formerly been used during slavery to house their enslaved servants. I mention this only because, as in the case of Brackettown, it’s difficult to know when these communities actually began, as evidences seem to indicate that many of the residents were occupying their land predating their official deeds of transfer, and also, because this is important to know as we’re finding that many of the original residents of these communities purchased their lands from their former “owners”, indicating that many of the original residents had prior familial connections to each other, having lived together as a community prior to owning their own properties.

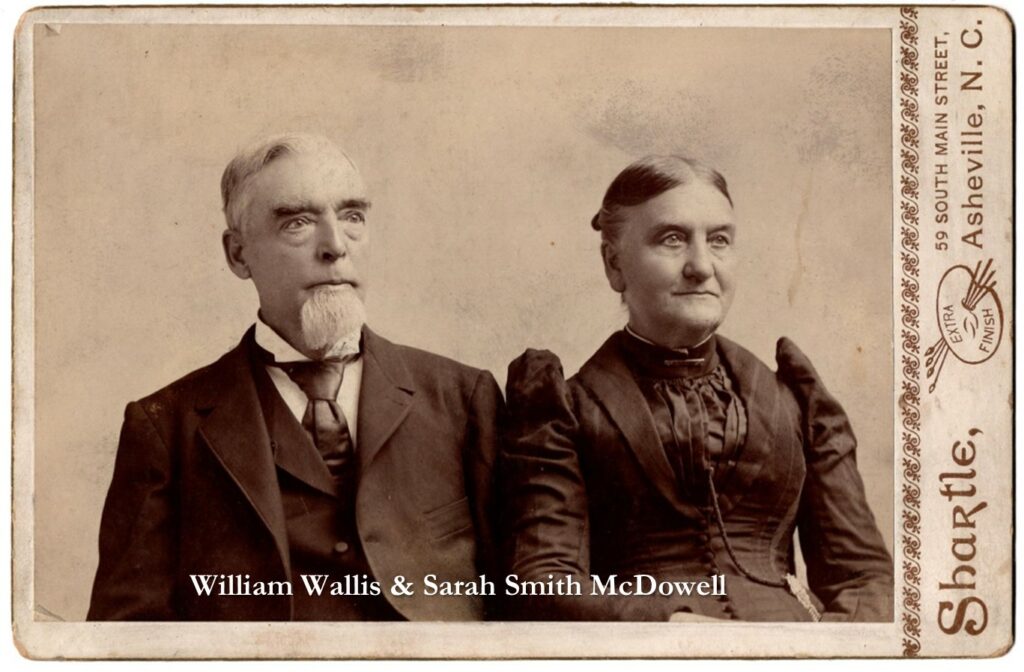

The full story of “Brackettown” has been told elsewhere, but for our purposes, let’s look at a brief history of its origins. The Brackettown community can trace its roots back mostly to the Smith and McDowell families. Around 1840, James McConnell Smith, who was rumored to be the first white child born west of the Blue Ridge in North Carolina, built “Victoria”, a large brick country house (today known as the Smith-McDowell house located at 283 Victoria Road) on his property overlooking the confluence of the Swannanoa and French Broad rivers. Although Smith built his house on the west side of S. Main Street (Biltmore Avenue), his property stretched across S. Main Street to the east to the western and southern slopes of Beaucatcher Mountain along the north side of the Swannanoa River. James M. Smith died in 1856, and the property was inherited by his son John Patton Smith. James Smith’s daughter, Sarah, and her husband, William W. McDowell, purchased the property at a foreclosure auction from her brother’s estate, following his (John Patton Smith) sudden death in 1857.

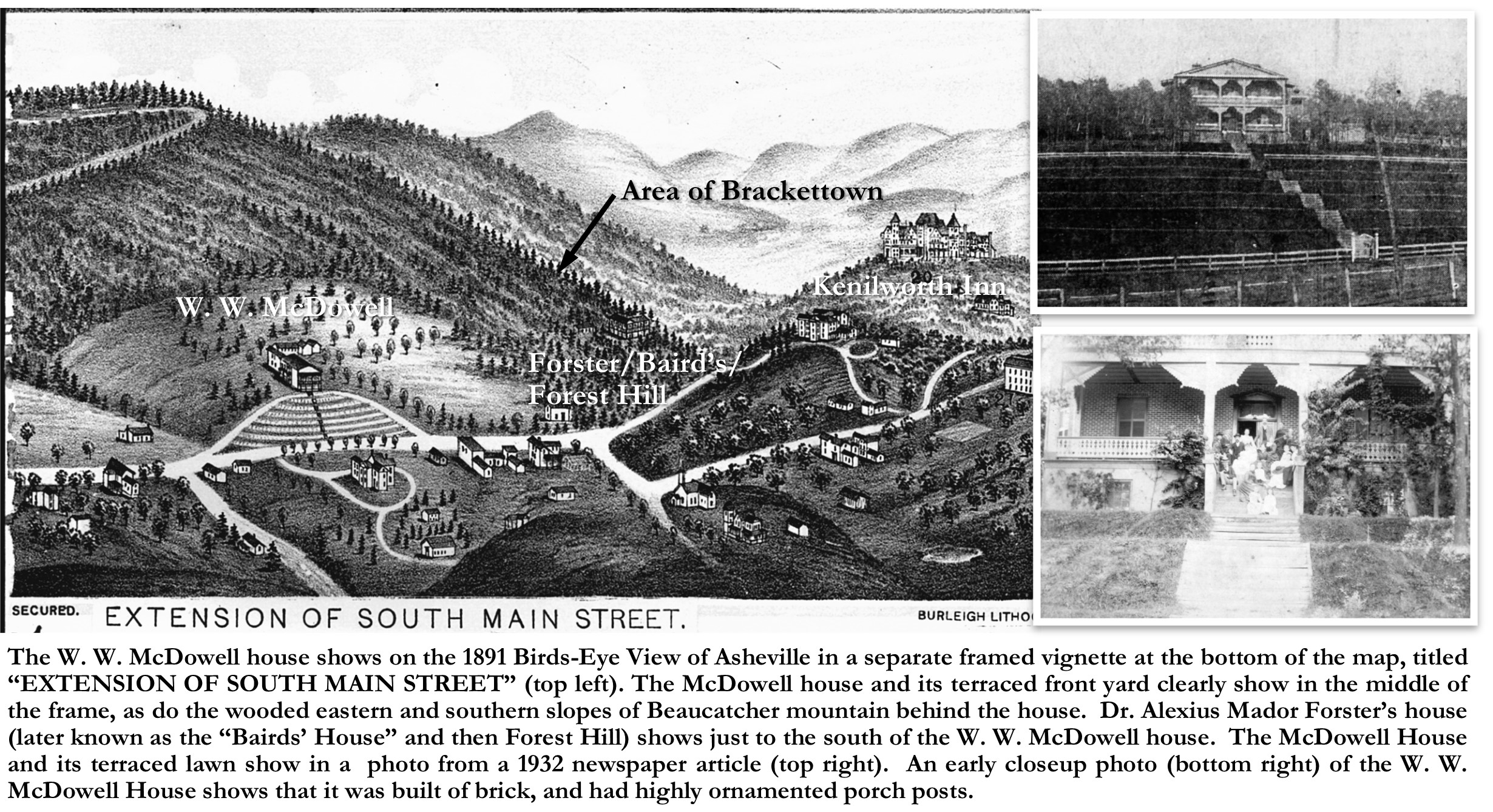

The McDowells raised their family in the Smith-McDowell House, but when in their late fifties, they decided to sell the house and a small portion of their property surrounding the house to Alexander Garrett of St. Louis, MO who had recently moved to Asheville. Upon the sale of the Smith-McDowell house, it was reported that W. W. McDowell “intends building a residence for his own use on the hill on the north side of Mr. Joseph Goodlake’s shops”.[23] Major McDowell built a new front-gabled two-story brick house on the east side of S. Main Street at 420 S. Main Street, now the site of the St. Joseph’s Hospital. In its time, the house was noted for its two-story front porch, and its unique terraced front lawn. The house and property show on the 1891 Birds-Eye View of Asheville in a separate framed vignette at the bottom of the map, titled “EXTENSION OF SOUTH MAIN STREET”. The McDowell house and its terraced front yard clearly show in the middle of the frame, as do the wooded eastern and southern slopes of Beaucatcher mountain behind the house. Dr. Alexius Mador Forster’s house also shows just to the south (right) of the W. W. McDowell house. Later known as the “Bairds’ House”, or most popularly as “Forest Hill”, Dr. Forster (of Friendfield Plantation, Georgetown, SC) had built his house as a summer home an 8-acre property that he purchased from James M. Smith in 1851, adding to the property with an additional 12 acres purchased from W. W. & Sara McDowell in 1859.[24] It was just around the bend of S. Main Street pass “Forest Hill” that Brackettown Road joined with S. Main Street, where Forest Hill Drive now enters Biltmore Avenue. Although it does not show on the birds-eye view, Brackettown had already been established on the wooded slopes of Beaucatcher behind the McDowell and Forster/Baird houses, on former Smith/McDowell lands.

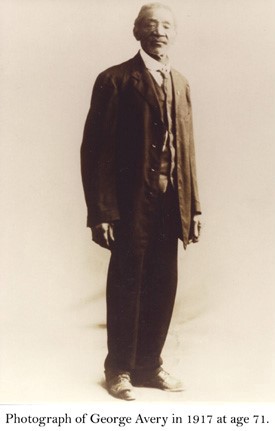

Hints from deeds and gathered research from Asheville’s South Asheville Cemetery, shows evidences that African Americans lived on the lands of Brackettown, long before any of them owned any property in the community. South Asheville Cemetery began as a slave burial ground, and its first known caretaker was an enslaved person named George Avery (1844-1938). Mr. Avery was owned by William Wallis McDowell (1823-1893), who lived in the Smith-McDowell House and after 1881, at 420 South Main Street. Mr. McDowell entrusted George Avery as the manager of this cemetery. Avery managed the cemetery until his death in 1938. Starting in the 1870’s and 1880’s, a community of African Americans, including George Avery, and “foreigners”, like “Ferdinand Neighbors” (who was a German immigrant whose real name was Ferdinand Nachbar) began to be established around the South Asheville Cemetery (mostly to the west and south). The cemetery was then accessed from Brackettown Road (on many plats it’s called Ross Creek Road), which ran just south of the cemetery.

In addition to the Smith-McDowell house and farm, that had been inherited by Smith’s son John Patton Smith, but later purchased from J. P. Smith’s estate, Sarah Smith McDowell had also inherited her own chunk of lands. In a deed dated, October 10, 1871 (though not registered until 1880), W. W. McDowell drew up a legal document in which his wife, Sarah L. McDowell agreed to sell off portions of the property that Sarah McDowell had inherited from her father, James McConnell Smith in South Asheville[25], to help pay her husband’s debts. In this 1871 deed, are fourteen properties on a list of the “Lands Sold belonging to Sarah L. McDowell”, including “One Lot Sold to Ben Ragsland (sp)-$300”. [26]

Just down the road (literally)from the South Asheville cemetery, on the west side of Brackettown Road, Ben Ragsdale built a substantial two-story house around 1889. Ben Ragsdale was born into slavery (around 1840)[27] and was owned by James McDowell Smith, and then was inherited by Smith’s son John Patton Smith. Ragsdale was bought by W. W. & Sara Smith McDowell at an estate sale, following the death of John Patton Smith in 1857 (John was Sara’s brother). Although President Abraham Lincoln had issued the “Emancipation Proclamation”, declaring all slaves to be freed, the enslaved people in Asheville and Buncombe County were not freed until late April of 1865 when Union General George Stoneman’s forces moved through the area, declaring and enforcing the proclamation. However, Ben Ragsdale, though freed, continued to work for the McDowell family, and live on McDowell land. In the 1870 and 1880 censuses, Ben Ragsdale is shown as living on part of the McDowell land that would become Brackettown (South Asheville).

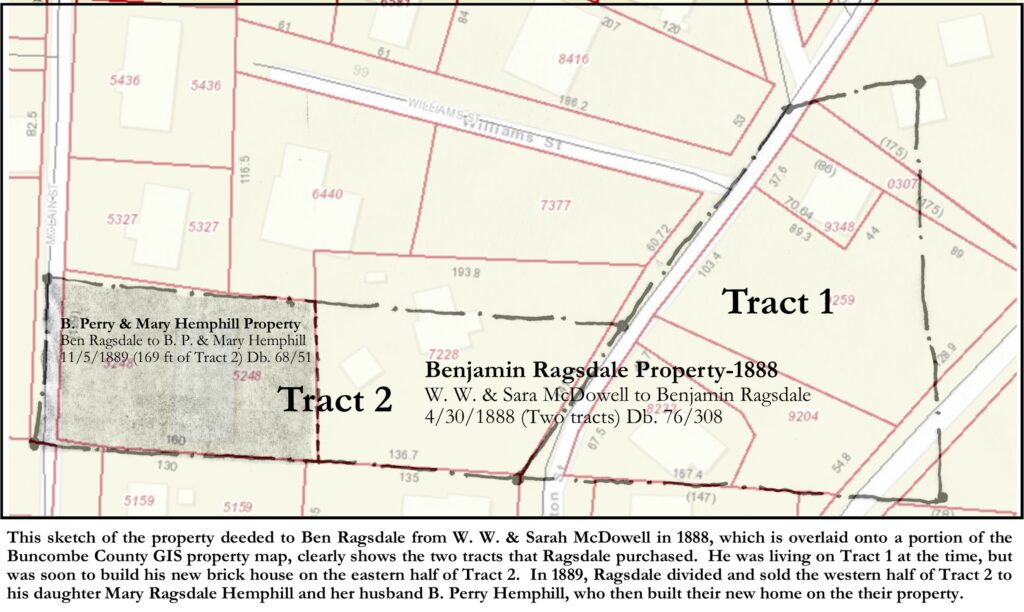

A search and study of the deed transfers of W. W. McDowell, between 1888 and 1890, shows that during that time, McDowell was selling off much of his property on the east side of S. Main Street including not only his own house at 420 S. Main Street, but also most of the remaining land behind his house, which included much of the Brackettown community. The property transfers for the majority of the first landowners of Brackettown, occurred during this period and were for land purchased from W. W. & Sara McDowell. Perhaps McDowell, who was aging and soon to die (in 1893), wanted to “settle his accounts”. As mentioned earlier, evidences seem to indicate that many of the residents were already living on their lands which they began purchasing from McDowell during that three-year period. Perhaps the occupants were first renting their properties from McDowell. Ben Ragsdale purchased his property, which straddled both sides of Brackettown Road, from McDowell in 1888.[28] Ragsdale’s purchase was for two-tracts, one on the east side of the road, and the other tract on the west side of the road. The deed states that this second tract, “is on the west side of the road, in front of R. B.’s house,” implying that Ben Ragsdale was already living in a house, on the tract on the east side of the road.

In 1891, Ben Ragsdale acquired a loan of three-hundred and fifty dollars from the Citizen’s Building and Loan Association,[29] for the purpose, I believe, of building his new brick home on the hill on his western tract. In addition to the three-hundred and fifty dollars in cash, Ragsdale also acquired five shares in the Association. Unlike acquiring a modern-day mortgage, the nineteenth century “Building and Loan Association” lenders operated much differently. Forbes magazine writer, John Wake gives us modern-day readers, whose only acquaintance with Building and Loan Associations is probably from seeing poor old George Bailey try to avert a run on his Building and Loan Association in the classic Christmas movie, “It’s a Wonderful Life”! Wake explains:

In real life, the way Building & Loan mortgages worked seems completely alien to us today. If you borrowed $2,000 to buy a house, depending on interest rates, you might pay $10 a month to the Building & Loan in interest. In addition, you might pay another $10 per month to the Building & Loan that, in its roundabout way, would eventually pay off your mortgage. That second $10 per month didn’t go to pay down the principal, and it didn’t go into a savings account so you could save up $2,000 to eventually pay off the mortgage. That $10 per month went to buy shares (stock) in the Building & Loan itself! Typically, after around 12 years in this scenario you would own $2,000 worth of shares in the Building & Loan and that’s how you paid off your mortgage. You used your $2,000 worth of shares to pay off your $2,000 mortgage all at once! A 12-year mortgage was about the longest mortgage you could get. The average mortgage from banks back then was only 4 years which helps explain why Building & Loans had about half of the mortgage market. The exact amount of time it would take you to pay off your Building & Loan mortgage was uncertain, however, because it depended on how much money you earned along the way in dividends from the shares you owned in the Building & Loan. Building & Loans were cooperatives where every shareholder had one vote no matter how many shares you owned. You had the same number of votes as Mr. Potter.[30]

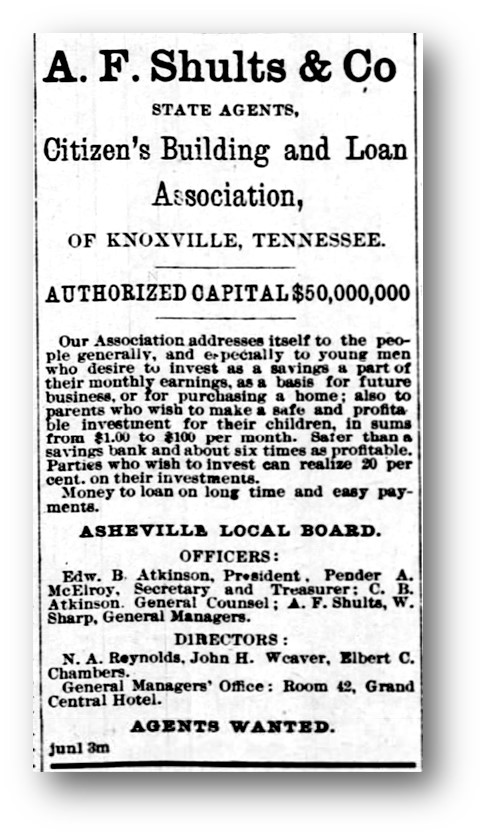

Although Asheville people would eventually form their own Building and Loan Association, the Citizen’s Building and Loan, from which Ragsdale obtained his mortgage, was based in Knoxville, Tennessee. A. F. Schults & Co., acting as “States Agents”, had just recently (June of 1891) opened an Asheville branch of the Citizen’s Building and Loan Association of Knoxville, Tennessee.[31] To their credit, the Asheville branch did have their own local board of directors. Perhaps Ragsdale was attracted by the advertisement that offered, “Money to loan on long time and easy payments”.[32]

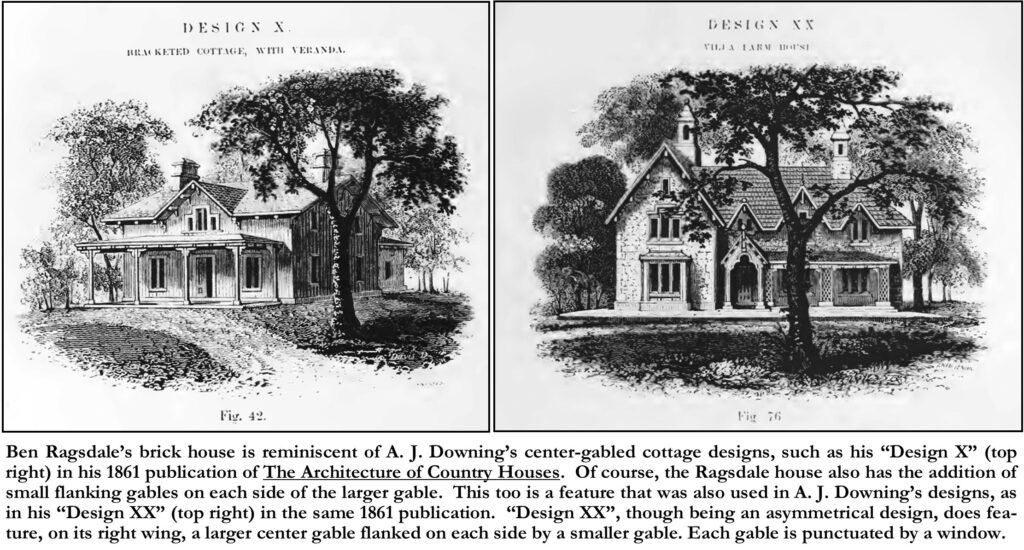

Ben Ragsdale built his brick two-story house (really a story-and-a-half) in a stylish, though outdated, early Victorian Gothic-Revival Cottage Style, as popularized by A. J. Downing during the 1840s-1860s. Though simplified and unornamented, Ragsdale’s brick house is reminiscent of Downing’s early center-gabled cottage designs, such as his “Design X” in his 1861 publication of The Architecture of Country Houses.[33] Downing’s “Design X” was titled “A Symmetrical, Bracketed Cottage, with Veranda”, which featured a 1-1/2 story cottage with a center front gable and a simple porch across the front. Of course, the Ragsdale house also has the addition of small flanking gables on each side of the larger gable. This too is a feature that was also used in A. J. Downing’s designs, as in his “Design XX -A Villa Farm-House in the Bracketed Style”[34], in the same 1861 publication. “Design XX”, though being an asymmetrical design, does feature, on its right wing, a larger center gable flanked on each side by a smaller gable. Both designs, just as on Ragsdale’s house, feature a low-knee wall for the front and rear second-story walls, punctuated by three gables, each having a center window. Although the current porch (veranda) on the Ragsdale house only straddles the center front door, the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps (from 1917-1951) indicate that the original porch was the full length of the front of the house, more in keeping with Downing’s cottage designs.

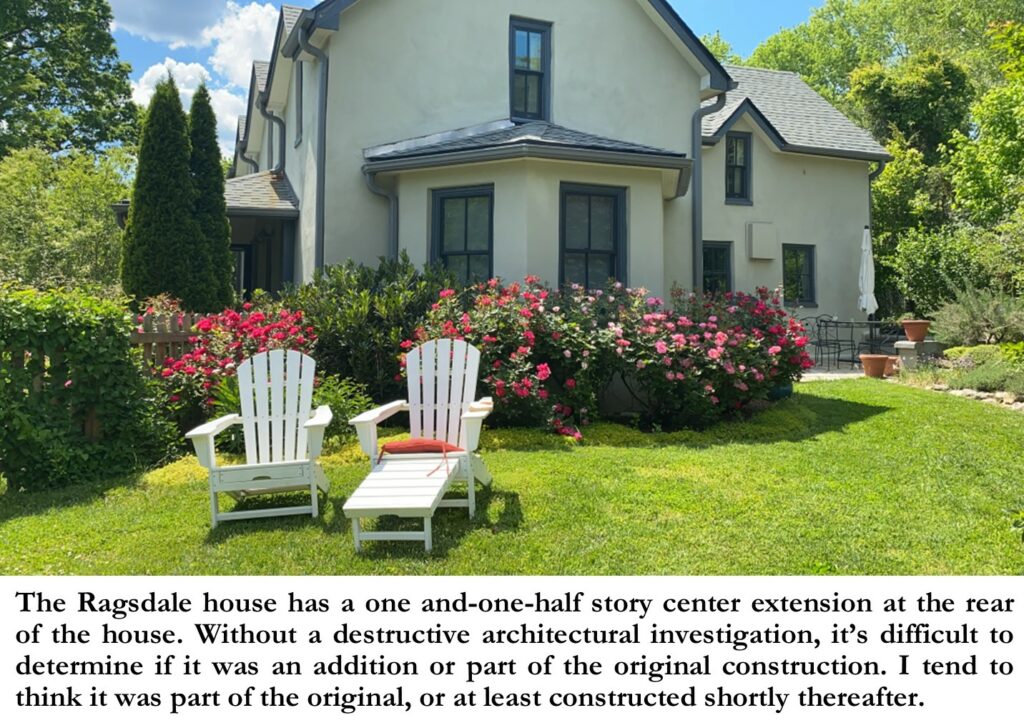

There is a one and-one-half story center extension in the rear of the house. Without a destructive architectural investigation, it’s difficult to determine if it was an addition or part of the original construction. I tend to think it was part of the original, or at least constructed shortly thereafter. The extension shows on the 1917 Sanborn Map, and as Ben Ragsdale died in 1914, after which the house became a rental for decades, I’m sure that the extension had to have been built prior to 1914.

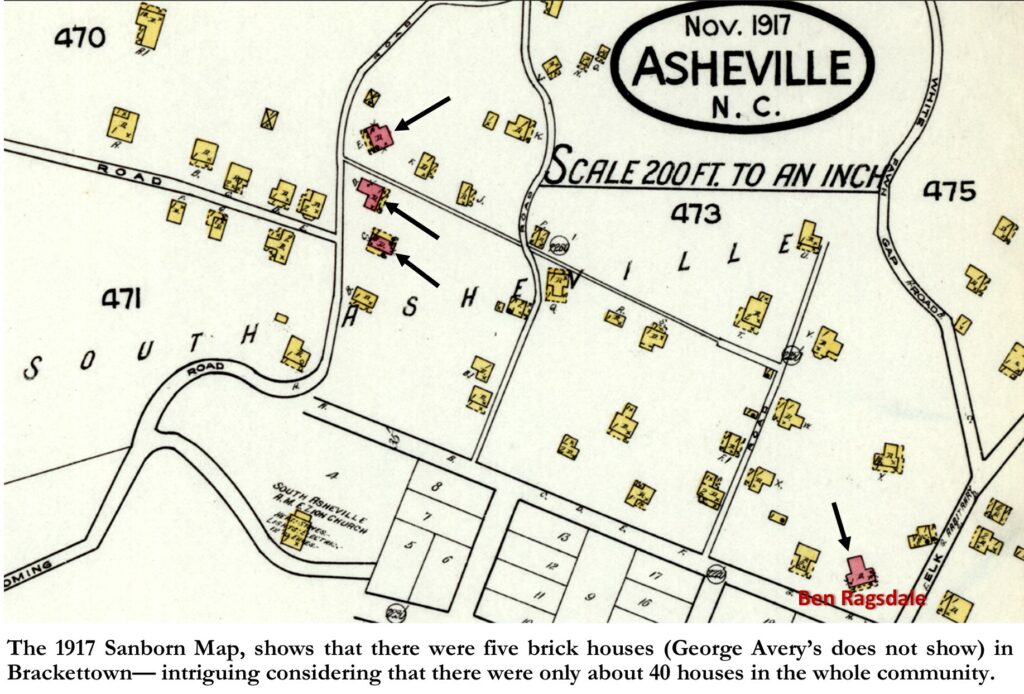

In investigating the building of Ben Ragsdale’s brick house, I noticed from the 1917 Sanborn Map, that there were five brick houses in Brackettown in 1917, which was intriguing considering that there were only about 40 houses in the whole community. Of course, that begged the question, why were there so many substantial brick houses in this small community, and when were and by (and for) whom were they all built? Interestingly, it appears that they were all five built during those same years as the early property transfers, 1888-1891, which could be deemed Brackettown’s “boom” years. It suggests that there may have been a conscious effort by the community leaders to establish Brackettown as a vital community, to counter the stereotype of African American communities just being made up of shacks, shanties, and tenement houses.

Lazarus Clayton, Sr. was one of the earliest landowners in Brackettown, having purchased a 4-acre tract from W. W. & Sarah McDowell in 1878.[35] In November of 1889, his son, Lazarus Clayton, Jr. (also known as L. L. Clayton) purchased a ½ acre lot, southwest of the Clayton home place (4-acre tract) from W. W. & Sarah McDowell.[36] I believe he purchased the lot to build a house to begin his own family, as the following month, twenty-one year old Lazarus, married eighteen year old Medear Forney.[37]

Clayton obtained a loan of $160 from Alexander Garrett, through R. U. Garrett to purchase the property in November of 1889.[38] The terms of the loan required Clayton to maintain insurance on all “buildings erected and to be erected” on the property. In May of 1891, Lazarus and his new wife, obtained a loan (deed of trust) of $650 from Mrs. J. E. Hawley, through R. U. Garrett acting as trustee.[39] Terms of this loan required Clayton to carry $500 worth of insurance on the property until the loan was paid-off. I assume that this loan functioned as a mortgage for the house that was already, or perhaps being erected.

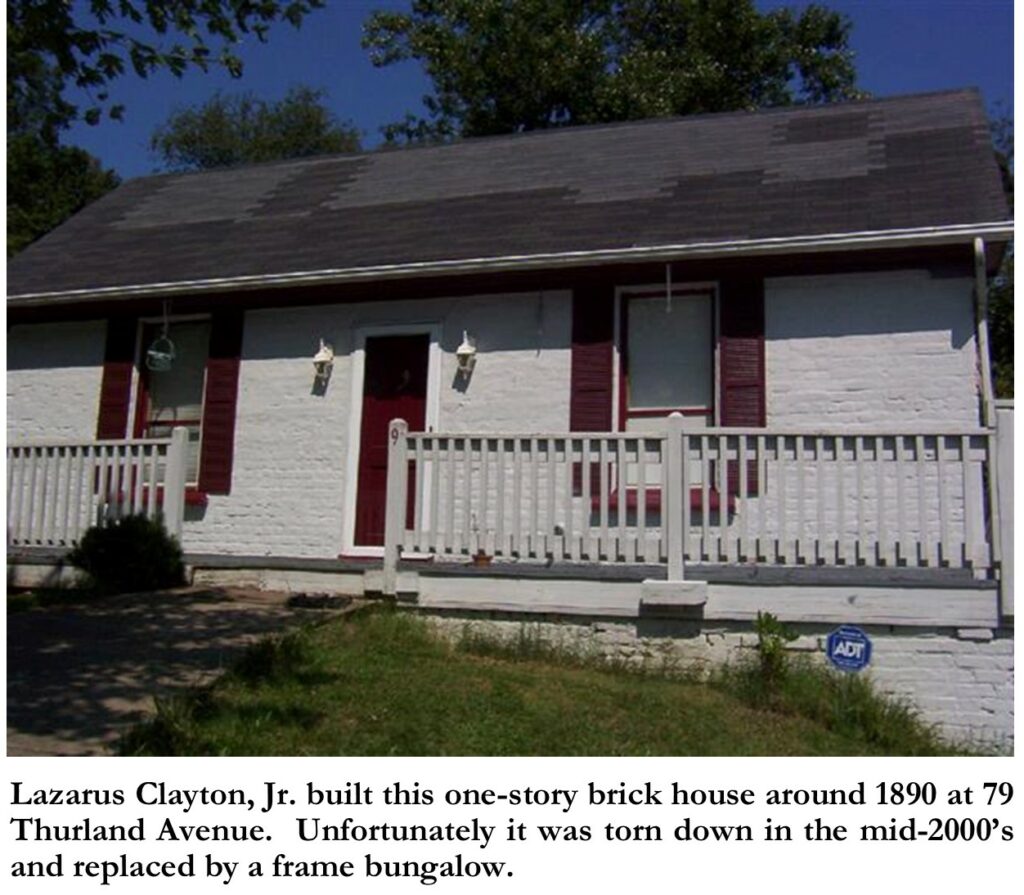

Lazarus & Medear Clayton chose to build a one-story, two-room brick “starter home”, with a large wrap-around porch on its west (front) and south sides. The Clayton house, which later became the home of Edward Keebler, was located on the lot that is now addressed 79 Thurland Avenue. Unfortunately, in March of 1899, perhaps due to a spot of legal problems (he was sent to “the chain gang” in November of 1899[40]), Clayton’s house and property were foreclosed on by R. U. Garrett, trustee of the 1891 loan from Mrs. J. E. Hawley.[41]

It’s not surprising that Lazarus Clayton, Jr. decided to build a brick house, as he was a bricklayer/brick mason. In the 1880 U.S. Census, at the age of 12, Lazarus was listed as having an occupation: “In Brickyard”. In the same census, his 17-year-old brother William Clayton was listed as being a “brick-molder”. In subsequent censuses, and even on his 1942 death certificate, Lazarus Clayton, Jr. listed his occupation as “brickmason”. Clayton’s brick house survived until the mid-2000’s, but then it was torn down and replaced by a frame bungalow.

Two other brick houses were built in Brackettown at the same time as the Clayton and Ragsdale houses. In fact, both houses were built on adjacent lots, adjacent to and south of Clayton’s house. On the 1917 Sanborn Map, the three brick houses show together on the eastside of Keebler Road. The brick house that was built just south of Lazarus Clayton, Jr.’s house, sat on the property that is now addressed as 59 Thurland (aka Lot 180, Ward 8, Sht. 3 on the Buncombe County Tax maps). It appears on the 1917 and 1925 Sanborn Maps as a one-story brick L-shaped house with a porch in the crux of the “L”. However, sometime between 1925-1950, it was replaced by the small frame house that is now on the site. This brick house at 59 Thurland Avenue appears to have been built for/by widow Manerva Randall in 1889, in conjunction with the building of a house next door at 24 Keebler Road (aka Lot 181, Ward 8, Sht. 3 on the Buncombe County Tax maps) for her son John Calvin Randall.

In 1889, Manerva Randall sold a “49/100ths” acre lot, to her son John Calvin Randall.[42] John C. Randall’s lot was a small portion of the 1.37 acre lot which Manerva Randall had recently (just the month before) purchased from W. W. & Sarah McDowell.[43] Manerva’s lot (which included J. C. Randall’s lot) adjoined the Randall homeplace lot to the south, which had been purchased in 1872, by Thomas Randall (Manerva’s deceased husband) from W. H. Rossell,[44] the owner of the “Swannanoa Hill” property. The Thomas Randall lot, in 1889, was then owned by Manerva’s son Lawson Randall, who incidentally, was a brick mason.

In May of 1889, John C. Randall and his mother, Manerva Randall, took out a deed of trust from R. U. Garrett & Alexander Garrett, for $262.50, against their shared but divided property.[45] In the description of the second tract of two tracts in this deed of trust, it describes the second tract as the same tract “upon which John C. Randall has just built his brick house”. Apparently, John C. Randall was in quite a hurry to build his new brick house, no doubt in preparation for his marriage to Mahala Ragsdale, the daughter of Ben Ragsdale, who was then building his own brick house, just east of the Randall house. John C. & Mahala obtained their marriage license a few months later in December of 1889.[46] In 1891, John and Mahala Randall took out 10 shares and a loan of $900 from the Citizen’s Building & Loan Association.[47] The lien on this loan was both against J. C. Randall’s lot at 24 Keebler Road (aka Lot 181, Ward 8, Sht. 3 on the Buncombe County Tax maps) and his mother Manerva’s lot/house (at 59 Thurland Avenue), on the adjacent lot to the north (aka Lot 181, Ward 8, Sht. 3 on the Buncombe County Tax maps). This loan of $900, I suppose, was to cover the mortgages on both houses, assuming that both brick houses had been completed. John & Mahala Randall enjoyed their new brick home for a few years, until selling it and his mother’s house (Manerva had passed in 1900) to investor Robert & Sophie Wills in 1902. J. C. & Mahala Randall then moved to Massachusetts.

The only known photo of the J. C. Randall house that we have is from a 1938 newspaper article, which unfortunately was reporting of its demise.[48] The house, which was then being used as a tenement house, had tragically been set ablaze by an explosion, when one of its tenants was attempting to light her gas stove. The photo shows that the Randall house was a one-room deep two-story brick house with side gables. The shape and massing of the Randall house was similar to the Ben Ragsdale house, except that the second story was full height, and the house had no front gables. The attic had full-length windows in each end gable, suggesting that it was no doubt used for sleeping. Apparently, the house was torn down shortly thereafter.

The fifth house to be built of brick was built by George Avery on a lot just northeast of Ben Ragsdale’s house, on the north side of Brackettown Road (Dalton Street), just south of the cemetery and what would later become St. John ‘A’ Baptist Church. Records show that Avery most likely built his house around the same time as Ben Ragsdale built his brick house. In March of 1890, W. W. & Sarah McDowell deeded a two-acre lot, between Brackettown Road and the cemetery, to George Avery.[49] In April of 1891, the Averys took out a deed of trust from John H. McDowell (businessman and son of W. W. McDowell) for $300.[50] This is most likely when the Averys began building their new brick house, as the terms of the deed of trust required them “to keep the building on said premises” insured against fire. Then in March of 1892, George Avery & Maggie Walker Avery (they married in 1884) obtained a deed of trust from the Covenant Building and Loan Association of Knoxville, TN.[51] This was a separate Building and Loan association from the aforementioned Citizen’s Building & Loan Association of Knoxville, but they operated in the same manner, and they too were considered a branch association and had their own local Board of Directors. The terms of Avery’s deed of trust was for five shares of stock in the association, with a loan of five-hundred dollars, which we can assume acted as a mortgage for his newly completed brick house. Records show that the Averys also used this deed of trust to pay off their previous loan from John H. McDowell.[52]

The George Avery brick house does not show on any Sanborn map, as it was built just pass the boundaries of the early maps. And we have no known photos of the house, and in fact we only know of its existence through oral history. George Gibson, one of the last residents to have been alive when George Avery was still around, recalls that the house was a two-story brick house. According to George Gibson, the Avery house had deteriorated after Avery’s death in 1938 and was later torn down by his adopted son Richard Houston.

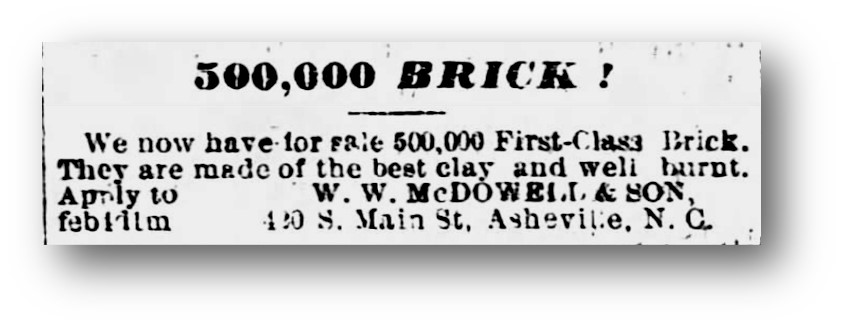

George Avery’s story has been told elsewhere, but the part of his story that is most interesting to our study of Ben Ragsdale’s brick house and the other brick houses of Brackettown, is that Avery was a brickmaker and friend of Ben Ragsdale. In 1870, George Avery was a “laborer” living with the Ben Ragsdale family. In the 1880 U.S. Census, 36-year-old George Avery was living with his first wife Percella and their 4-month-old son William, in a house next door to the Ragsdales. George Avery’s occupation was listed as “Molding Brick”.[53] Avery was a servant of the McDowell family, and in the 1880’s he supervised W. W. McDowell’s brickyard, which was located on the west side of S. Main Street, on McDowell Street just south of Southside Avenue, on Smith/McDowell lands. Although I cannot find an official name for the brickworks on the McDowell property there is adequate documentation verifying that it was in operation during the 1880’s through the early 1900’s. An 1888 advertisement in the Asheville Citizen-Times, titled “500,000 BRICK!”, announced that “We now have for sale 500,000 First Class Brick. They are made of the best clay and are well burnt. Apply to W. W. McDOWELL & SON, 420 S. Main St., Asheville, N.C.” [54] Also, a 1906 Plat, titled “Property of W. W. McDowell” (which technically by then was of his estate), shows a portion of the McDowell property on the south side of Southside Avenue.[55] A street shows on the plat, starting at the bend in Southside Avenue, heading east toward Biltmore Avenue, and that street is labeled as “Brickyard (Choctaw) Street”. “Brickyard Street” is shown crossing McDowell Street. This coincides with other sources which point to the McDowell brickyard being at the end of McDowell Street, south of Southside Avenue. Another piece of evidence that George Avery worked at the McDowell brickyard, is from a reference from the 1900 Asheville City Directory, under the listings for “BRICK MKRS”, is the entry, “Avery, Geo (c). McDowell St.”.[56] I can find no transfer of deed of this property to Avery, but I suspect by then Avery had some type of business agreement or lease with the McDowell estate to operate their brickmaking enterprise.

Oral tradition says that George Avery made the bricks for his house from the brickyard that was “in the flats”, along the southern edge of Wyoming Road, just below the Brackettown (South Asheville) community, site of the present-day Kenilworth Park. However, I suspect that the bricks for Ben Ragsdale’s house, as well as for the other four brick houses (including George Avery’s) came from the McDowell brickyard. Especially since all other evidences indicates that the five brick houses in Brackettown were built between the period of 1888-1891, because the brickyard that was off of Wyoming Avenue was not established until 1906, when George C. Shehan purchased the property from the Kenilworth Land Company and established the “Kenilworth Brick Company”.[57] In fact, the brickyard was only temporary in a sense, as Shehan’s deed to the property (Lots 43, 44 and part of Lot 56-from Plat 121/346) came with three conditions: one that Shehan erects three brick cottages (of at least four rooms each) on the site within five years; two, that Shehan construct a road through the property from Wyoming Road to Caledonia Road; and three, that after five years, or after all the clay has been extracted from the site, Shehan is to remove “all machinery from the said premises”. By December 1912, the Kenilworth Brick Works was defunct and the bricks from the former brick kiln walls were being offered for sale.[58] Also, judging from the 1917 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, it appears that Shehan never built the required “three brick cottages”. But no matter in which brickyard the bricks for those first five brick houses in Brackettown were made, it is for certain that the bricks were made by African Americans and were made locally. I also suspect that the bricks for those houses were laid by an African American brick masons that lived in the Brackettown community or the Southside community (on the west side of Biltmore Avenue where the McDowell brickyard was located). Possible suspects, some of which have been mentioned above, I conclude to be George Avery, John C. Randall, Lazarus Clayton, Jr., and James J. Bailey.

“Brackettown” is now a forgotten placename in Asheville and Buncombe County, however remnants remain, like the South Asheville Cemetery and Ben Ragsdale’s brick house, that remind us that at one time, Brackettown was its own separate community. And though most of the original houses are gone, and now replaced with modern “in-fill” houses, and though most of the original streets have been removed or rerouted and new streets added, Ben Ragsdale would be pleased to know that his house is not only still standing but looks as fine and beautiful as it did when he first built his brick house on the hill.

Photo & Image Credits: (All cropping, labels, and captions by Dale Wayne Slusser)

Brackettown Street Sign- Photo by Dale W. Slusser, 2023

Edwin Pascal Davis Portrait- Edwin Pascal Davis from Davis Bros. Photographers Portsmouth, NH. http://edwinpascaldavis.blogspot.com/2009/

1901 U.S.G.S. Topographical Survey- file:///C:/Users/dslus/Downloads/NC_Asheville_161703_1901_125000_geo.pdf

Willie Park, Jr.- Wikimedia: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2344880

Kenilworth Park Pavilion- Image MS282.001F photo J-Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Men on Horses on Patton Farm Road- Image N801-5A -Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Unpaved Road Kenilworth- Image N814-5-Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Google Terrain Map- Map Data ©2023 Google, Scale: 200 ft- https://www.google.com/maps/place/Chiles+Ave,+Asheville,+NC+28803

Plat of McDowell’s Land- 01/01/1887 MCDOWELL PROPERTY – PLAT ON SWANNANOA RIVER Db. 8/67. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Rossell Plat- 01/11/1887 R. B. Justice, T. W. Patton, A.T. Summey for W. H. Rossell Est. to Hugh B. Rossell and Sophia Rossell BUNCOMBE TURNPIKE ROAD & PLAT Db. 57/348. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

W. & Sarah McDowell Portrait- Collection of the Asheville History Museum, 283 Victoria Rd, Asheville, NC 28801.

Extension of South Main Street- Ruger & Stoner, and Burleigh Litho. bird’s-eye view of the city of Asheville, North Carolina. [Madison, Wis, 1891] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694894/

1932 Photo-McDowell House- Asheville Citizen-Times, March 6, 1932, page 28. -newspapers.com

Closeup Photo of McDowell House- Image A513-8-Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

George Avery Portrait- Collection of the Asheville History Museum, 283 Victoria Rd, Asheville, NC 28801.

Ben Ragsdale’s Brick House- Photo by C. R. Bell

Ragsdale Property Sketch- Sketch by Dale W. Slusser, over Buncombe County GIS Map- https://gis.buncombecounty.org/buncomap/

Citizen’s Building & loan Association Advertisement- The Asheville Democrat, June 25, 1891, page 7. -newspapers.com

Design X- The Architecture of Country Houses: including designs for cottages, farm-houses, and villas, with remarks on interiors, furniture, and the best modes of warming and ventilating. By Andrew Jackson Downing. (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1861), page 119.

Design XX- The Architecture of Country Houses: including designs for cottages, farm-houses, and villas, with remarks on interiors, furniture, and the best modes of warming and ventilating. By Andrew Jackson Downing. (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1861), page 170.

Side & Rear Extension Ragsdale House- Photo by C. R. Bell

1917 Sanborn Map- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Asheville, Buncombe County, North Carolina. Sanborn Map Company, Nov, 1917. Map- Sheet #43. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn06372_008/

Lazarus Clayton Jr. House-79 Thurland Avenue- Property Card for 79 Thurland Avenue, Asheville, NC, 28803 – https://prc-buncombe.spatialest.com/#/property/964864763500000

8 Thurland Avenue Fire Photo- (address is now 24 Keebler Road) –Asheville Citizen-Times, November 23, 1938, page 1. -newspapers.com

1926 Aerial Photo of Kenilwoth/Brackettown- Image MS282.001F photo B -Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

“500,000 Brick” Advertisement- Asheville Citizen-Times, February 28, 1888, page 4. -newspapers.com

Brick House at 2 Dalton Street- Photo by C. R. Bell

[1] Published online- Sunday, January 11, 2009- Margaret “Grits” Davis recollections- Aunt Grits’ Recollections at http://edwinpascaldavis.blogspot.com/2009/01/margaret-grits-davis-recollections.html

[2] A History of Buncombe County-Volume II, by Dr. Foster Alexander Sondley. (Asheville, NC: The Advocate Printing Company, 1930), page 625.

[3] 11/19/1889 E. P. Davis to Charles B. Benedict ROSS CREEK Db. 68/122. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[4] 09/22/1900 Thomas Wilmarth, Exc.; Charles B. & Mary E. Benedict to Erwin W. & Ellen A. Patton 70 ACRES ROSS CREEK Db. 115/481. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[5] 09/22/1910 Francis G. & Margaret P. (Aunt Grits) Goodale; Minot & Mary Davis to Henry H. Briggs 128 ACRES SWANNANOA ROAD Db. 170/383. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[6] 12/11/1916 Erwin W. & Ellen A. Patton to Happy Valley Company 46 ACRES ON ROSS CREEK Db. 211/355. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[7] “NEW KENILWORTH INN WILL RAISE FROM ASHES”, Asheville Citizen-Times, January 21, 1912, pages 1 and 8. -newspapers.com

[8] 03/03/1917 Erwin W. & Ellen A. Patton to Paul Roebling ADJ DR H H BRIGGS BRACKETOWN RD Db. 212/152. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[9] “NEW CORPORATIONS”, The News and Observer, Charlotte, NC, September 12, 1916, page 5. -newspapers.com

[10] “HAPPY VALLEY CLUB ORGANIZED”, Asheville Times, December 9, 1916, page 8. -newspapers.com

[11] “NEW GOLF COURSE AT KENILWORTH”, Asheville Times, November 20, 1916, page 12. -newspapers.com

[12] “URGE GOLF COURSE FOR KENILWORTH SOLDIERS”, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 16, 1918, page 10. -newspapers.com

[13] 12/30/1918 Happy Valley Country Club, Inc. to H. H. Briggs 45 ACRES CHUNNS COVE Db. 221/6. -Buncombe County register of Deeds.

[14] 11/12/1919 -C. Brown, Trustee for Central Bank for Paul Roebling to H. H. Briggs (sold on Court house steps) Db 234/506.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[15] FORTY ACRE LAKE BEING PLANNED IN CHUNNS COVE”, The Asheville Times, March 8, 1923, page 1. -newspapers.com

[16] Asheville Citizen-Times, August 27, 1924, page 7. -newspapers.com

[17] 12/14/1925 Kenilworth Lake Company -INC. Db. C008/87. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[18] Scrapbook titled, “Kenilworth Lake Construction”, MS105.001E -Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

[19] From Scrapbook titled, “Kenilworth Lake Construction”, N801-5A & N801-5B – Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

[20]Scrapbook titled, “Kenilworth Lake Construction”, MS105.- N814-5 – Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

[21] 01/01/1887 MCDOWELL PROPERTY – PLAT ON SWANNANOA RIVER Db. 8/67. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[22] 01/11/1887 R. B. Justice, T. W. Patton, A.T. Summey for W. H. Rossell Est. to Hugh B. Rossell and Sophia Rossell BUNCOMBE TURNPIKE ROAD & PLAT Db. 57/348. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds. Note: Hugh B. Rossell and Sophia Rossell were brother and sister, heirs/children of W. H. & Margaret Rossell.

[23] The Asheville Weekly Citizen, March 4, 1880, page 1. -newspapers.com

[24] 8/4/1851 (rec’d- 12/20/1861) James M. Smith to A. M. Forster 8 ACRES SWANNANOA Db. 27/170.; 10/20/1859 (rec’d-02/29/1860) W. W. & Sarah McDowell to A. M. Foster(sp) 12 ACRES SWANNANOA RIVER Db. 26/634. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[25] “Last Will and Testament of James M. Smith”, James McConnell Smith’s Will-dated: February 9, 1850. Death: May 18, 1856. -ancestry.com

[26] 10/20/1871 (rec’d-07/29/1880) W. W. McDowell to Sarah L. McDowell – Db. 40/457.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[27] His death certificate in 1918 lists his age as “around 70”, which would have been 1848, however the various censuses say he was born in 1840. -ancestry.com

[28] 4/30/1888 (rec’d-12/18/1891) W. W. & Sarah McDowell to Benjamin Ragsdale ASHEVILLE TS Db. 76/308. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[29] 10/07/1891 (rec’d-10/09/1891) Benjamin Ragsdale to Citizen’s Building and Loan Association, [D/T] CORRECTED 7/7/2020 Db. 27/78.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[30] “What ‘It’s A Wonderful Life’ Shows Us About the Weird History Of Building & Loans”, John Wake, Contributor– Dec 31, 2021, -https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnwake/2021/12/31/its-a-wonderful-life-and-the-weird-history-of-building loans/?sh=192da1d63199

[31] Advertisement, Asheville Democrat, June 11, 1891, page 5. -newspapers.com

[32] Ibid.

[33] The Architecture of Country Houses: including designs for cottages, farm-houses, and villas, with remarks on interiors, furniture, and the best modes of warming and ventilating. By Andrew Jackson Downing. (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1861), page 119.

[34] Ibid., page 170.

[35] 02/23/1878 (rec-d- 08/22/1891) W. W. & Sarah McDowell to Lazarus Clayton 4 ACRES TOWN MOUNTAIN Db. 79/45. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[36] 11/08/1889 (rec’d-11/11/1889) W. W. & Sarah McDowell to Lazarus Clayton ASHEVILLE TS Db. 68/79. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[37] 12/09/1889- L. L. Clayton married Median (sp) Forney by Rev. E. J. Carter, Witnesses: James & Magie Forney and S. R. Keplee- ancestry.com

[38] 11/11/1889 Lazarus Clayton to R. U. Garrett, trustee for Alexander Garrett [D/T] Db. 18/154.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[39] 05/16/1891 Lazarus Clayton to R. U. Garrett, trustee for Mrs. J. E. Hawley [D/T] Db. 25/97. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[40] “Will Hemphill and Lazarus Clayton, colored, were sent to the chain gang for failure to pay costs.”, Asheville Citizen-Times, October 24, 1899, page 4. -newspapers.com

[41] “Notice”, Asheville Times, March 24, 1899, page 7. -newspapers.com

[42] 02/16/1889 (rec’d-02/20/1889) Manerva Randall to John C. Randall ASHEVILLE TWP Db. 64/574. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[43] 01/10/1889 (rec’d-02/20/1889) W. W. & Sarah McDowell to Manerva Randall ASHEVILLE TS ADJ ROSSELL ESTATE Db. 64 /567. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[44] 05/06/1872 (rec’d- 01/02/1889) William H. & Margaret D. Rossell to Thomas Randall 1 ACRE ADJ F NEIGHBORS Db. 64/268.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[45] 05/02/1889 John Randall, Manerva Randall to R. U. Garrett, trustee for Alexander Garrett [D/T] CORRECTED 6/22/2020 Db. 16/230. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[46] The Asheville Democrat, December 12, 1889, page 1. -newspapers.com

[47] 12/14/1891 John C. & Mahalia Randall to Citizen’s Building & Loan Association Db. 27/344. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[48] Asheville Citizen-Times, November 23, 1938, page 1.

[49] 03/14/1890 (rec’d-04/18/1891) W. W. & Sarah McDowell to George Avery 2 ACRES ASHEVILLE TS Db. 77/238. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[50] 04/08/1891 (rec’d-04/18/1891) George & Maggie Avery to J. J. Graham, trustee for John H. McDowell [D/T] Db. 25/1- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[51] 03/25/1892 George & Maggie Avery to Covenant Building & Loan Association [D/T] CORRECTED 7/7/2020 Db. 28/366. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[52] 04/08/1891 (rec’d-04/18/1891) George & Maggie Avery to J. J. Graham, trustee for John H. McDowell [D/T] Db. 25/1- Buncombe County Register of Deeds. Note on left margin of first page states: “I, J. R. Graham, Trustee hereby acknowledge satisfaction in full of this deed of trust…March 31st, 1892…”.

[53] 1880 United States Federal Census for Geo. Avery, -Asheville, Buncombe, North Carolina-035. -ancestry.com

[54] “500,000 BRICK!”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 28, 1888, page 4. -newspapers.com

[55] 01/27/1906 W. W. McDowell PLAT SOUTHSIDE AVENUE & MC DOWELL STREET Db. 8/66. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[56] Maloney’s 1900-1901 Asheville, N. C. City Directory, (Atlanta, GA: Maloney Directory Company, 1900), page 321. https://lib.digitalnc.org

[57] 10/06/1906 (rec’d- 10/09/1906) Kenilworth Land Company to George C. Shehan KENILWORTH Db. 144/313. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[58] “FOR SALE-at greatly reduced prices, 75,000 brick. These walls were the kiln walls of the Kenilworth Brick Company, and are in fine condition.”, Asheville Citizen-Times, December 18, 1912, page 11. -newspapers.com