by Dale Wayne Slusser

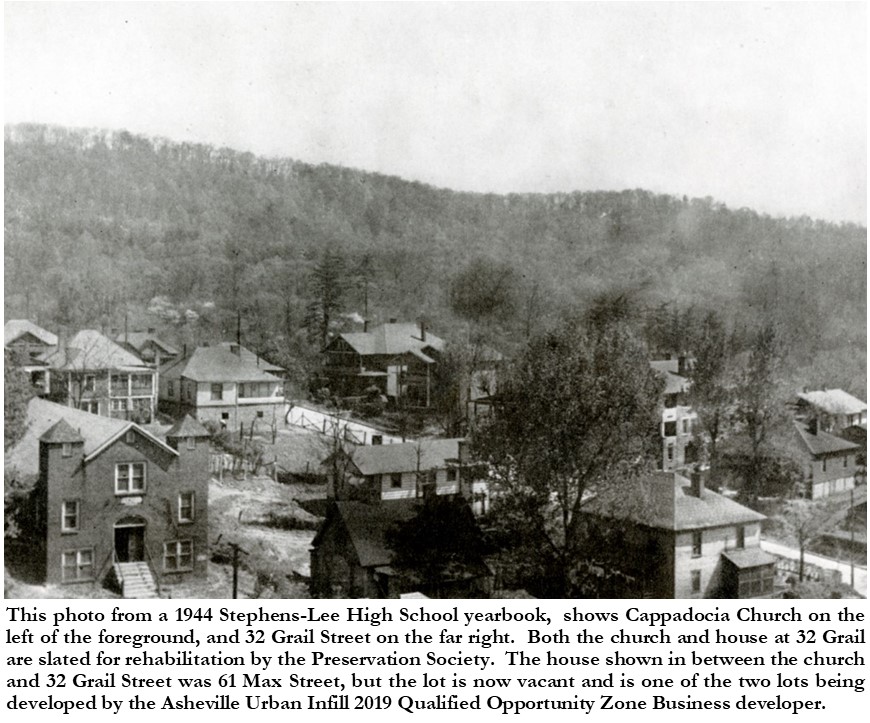

The Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County has recently purchased the Cappadocia Church in Asheville’s East End neighborhood, a historically African American neighborhood on the western slope of Beaucatcher Mountain. The church property and an adjacent residence along with two adjacent vacant lots had previously been purchased by a developer who intended to demolish the church and house and use the four lots for a multi-family infill project. In an example of how preservation and development can coincide and even cooperate with each other, the developer was willing to sell the church and existing residence to the Preservation Society for rehab/restoration, while retaining the vacant lots for the developer’s infill development. But why save this church which seemed relatively unknown in Asheville’s historic annals, and which appears to have little architectural significance? The short answer is that although the church seemed to be relatively unknown, that in fact besides having been a significant part of its neighborhood for over a century, it does have a rich history and is representative of the African American post-reconstruction struggle to survive and thrive in a segregated community.

Noted historian Darin J. Waters, Ph. D[1], in his dissertation, “Life Beneath The Veneer: The Black Community in Asheville, North Carolina from 1793 to 1900”, gives us a general overview of the conditions of the Black Community in post-Civil War/Reconstruction Asheville, which created the environment from which Cappadocia Church (and many other Black churches) were birthed:

Establishing religious and educational institutions was as important as finding jobs to blacks in post-Civil War Asheville. During slavery, their access to an education had been strictly forbidden, but religious instruction was sometimes allowed under the careful supervision of whites, who attempted to use religion as a means of social control. Despite this fact, however, blacks still found ways to shape religion to their own purposes, making its message of spiritual liberty a source of encouragement and inspiration. After the Civil War, religion and religious institutions retained their importance to blacks. In Asheville, blacks used their religious institutions not only to improve their spiritual lives, but also to lay the foundations for a much broader program of nonsectarian education in the city and surrounding region. These institutions proved to be important to the efforts that blacks made to strengthen their freedom and independence after slavery.[2]

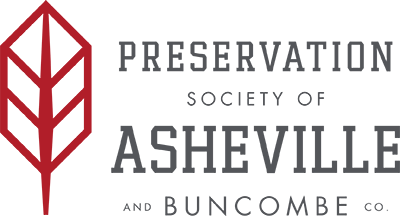

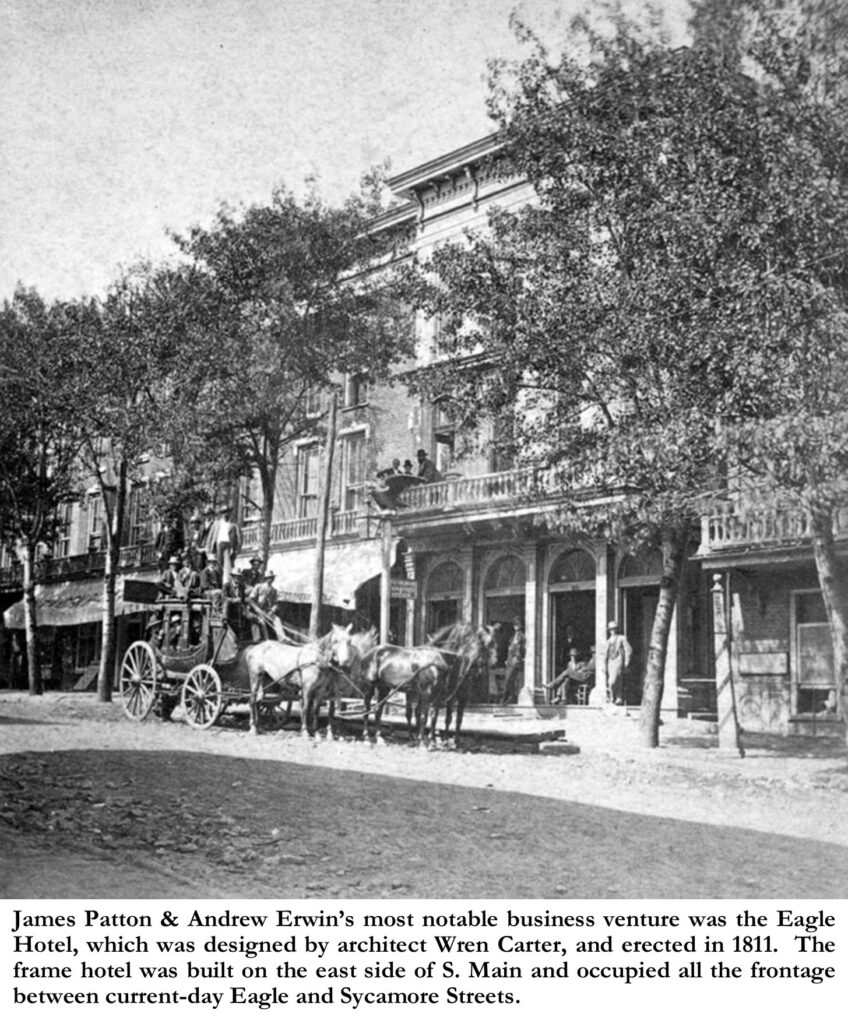

The hill on which Cappadocia Church would be built, known as “Catholic Hill”, has an interesting history that illustrates the early development of the “East End”, which by the 1890’s had become a distinctly African American neighborhood. The hill was originally both part of a 36-acre parcel purchased in 1807 by James Patton and his brother-in-law Andrew Erwin (early founders of Asheville) from John Patton (not related)[3], and part of a 180-acre tract purchased by Patton & Erwin from John Strother in 1799[4]. The 36-acre parcel was adjacent to the east boundary, at the southeast corner, of the original 200-acre Asheville “Town tract”, which had been purchased and plotted by John Burton in 1794.[5] The 36-acre parcel purchased by Patton & Erwin was directly behind their block of Town Tract lots which they had purchased between present-day Eagle and Sycamore Streets on the east side of S. Biltmore Avenue. The 36-acre parcel which straddled present-day S. Charlotte Street (which mostly follows the former Valley Street) included much of the upstream portion of “Town Branch”, known to today’s readers as “Nasty Branch”, which according to an 1886 map of Asheville, has its headwaters on Town Mountain. The 180-acre parcel, which was adjacent to the east of the 36-acre parcel, encompassed most off the west slope of Town Mountain (Beaucatcher Mountain) and most of what would become the “East End” neighborhood. Both parcels as well as the Town Branch show on a composite survey of the various parcels which made up the early town of Asheville. This composite survey is part of the material that was donated to the Old Buncombe County Genealogical Society in 2014 by Ralph Hammond, who was married to a descendent of James Patton.[6] The material was in the Clara Patton Murphy house which sat on the west side of S. Tunnel Road. Clara Patton Murphy was the granddaughter of James Patton and had built her house on the site of the original James Patton house which he had built in 1807.

“About the year 1800 two merchants in partnership, living in Wilkes County, who did business under the names of Patton & Erwin, purchased large possessions of choice lands on Swannanoa River with a store and boarding-house in Asheville,” recollected an eyewitness in an 1875 news article. [7] The eye witness, identified only as “McD”, who had moved to Asheville in 1812, further described the two partners: “James Patton was a remarkably plain unpolished Irishman of fine mind and sound judgement, while his junior partner, Andrew Erwin, in all respects was his antipode—showy, plausible and of strong mental powers; but his fine mind lacked ballance [sp] and to his ultimate financial ruin, in speculation he was far reaching and visionary.”[8] Together the partners established a number of businesses, including a store on the west side of S. Main Street (Biltmore Avenue), a hemp factory for making cloth bags, a rope factory, a factory for making “saddle-trees”, a saddler shop, blacksmith, and tannery. But Patton & Erwin’s most notable business venture was the Eagle Hotel, which according to the article, was designed by architect Wren Carter, and erected in 1811. The frame hotel was built on the east side of S. Main and occupied all the frontage between current-day Eagle and Sycamore Streets. According to historian Foster S. Sondley, the “tanyard stood on the west side of where Valley Street [S. Charlotte Street] now runs at a big poplar near where that street enters South Main Street [Biltmore Avenue]”.[9] I suspect that the saddler shop and blacksmith were also on the west side of Valley Street, but a bit further north, almost directly behind the Eagle Hotel. The Hotel and accompanying businesses- store, tanyard, saddler, blacksmith, and rope factory, required a good deal of what today we call “staff”, which in Patton and Erwin’s day, sadly mostly consisted of enslaved African Americans. “The sad truth is that the rich and powerful families of Buncombe County were slave owners, and that their wealth depended in large part on their “ownership” of other human beings.”[10] The lodgings for the enslaved African Americans, which were no doubt little better than shanties, were built in the valley behind and below the Hotel, as Patton & Erwin owned all the land behind the hotel, including most of the western slope of Beaucatcher Mountain. These shanties would become the embryo of the growth of the African American neighborhood of the East End.

The partnership between James Patton and Andrew Erwin was dissolved, according to James Patton’s autobiography,[11] in one day, on March 11, 1814. According to eyewitness “McD”, the reason for the dissolution of the Patton & Erwin partnership, was that Patton was alarmed by what he saw as Erwin’s “reckless course”, as Erwin “had purchased thousands of acres of land-claims in Middle Tennessee.”[12] Erwin sold all his interests in the business to James Patton. In 1835, James Patton put all his business interests, under the management of his son James W. Patton. Upon James Patton’s death in 1846, James W. Patton inherited most of the Asheville city lands and property, which also included numerous enslaved African Americans.

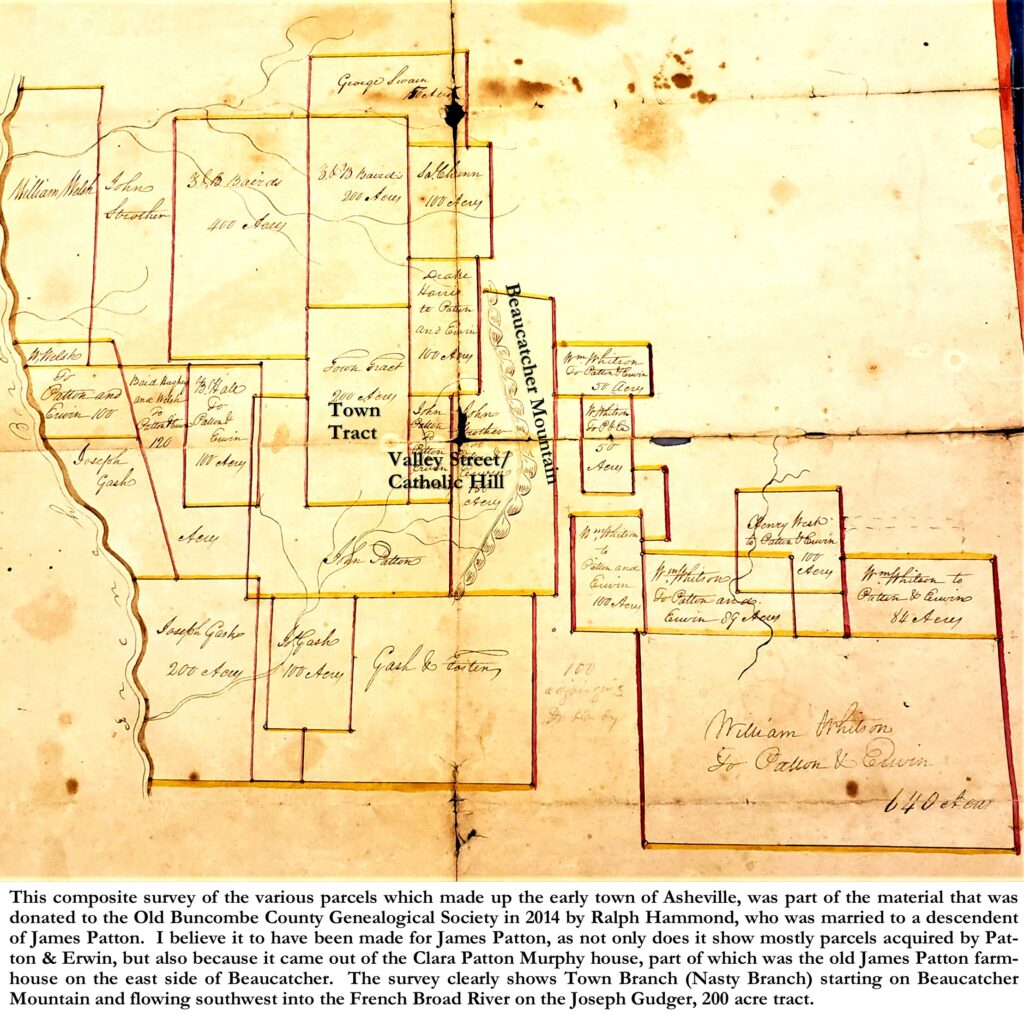

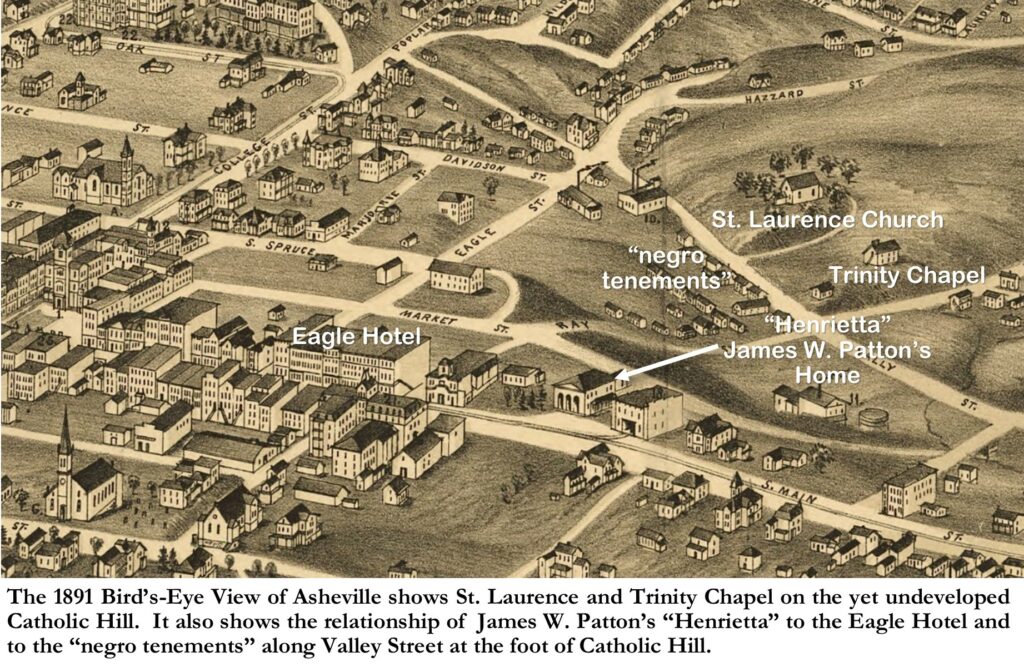

In 1857, James W. Patton built a Greek Revival Mansion, which he named “Henrietta” on the east side of South Main Street, south of the Eagle Hotel. He named the house after his second wife, Henrietta Kerr Patton, who he had married in 1839, and who had borne his two youngest children, Fannie Louise, and Thomas Walton. James W. Patton died in 1861 leaving his properties and enslaved African Americans divided up between his wife, daughter and three surviving sons[13], William A., James A., and Thomas W. Patton. However, his sons William and James who had been given the bulk of the businesses (Hotel, Store, and tanyard, etc.) both died during the Civil War from mortal wounds (William in 1863 & James in 1864) leaving the burden of the management of the Patton estate to their younger half-brother Thomas Walton Patton. The “Henrietta” house and surrounding land, which included all of what would become Catholic Hill, was willed by James W. Patton to his wife Henrietta, with a half-interest to his daughter Fannie Louise. Henrietta Patton’s legacy alone also included over twenty enslaved African Americans, and overall, James W. Patton had willed about eighty slaves to his various legatees. As most of these enslaved people worked in Patton’s various Asheville businesses, no doubt they lived in the “negro quarters” on the land behind the Eagle Hotel and “Henrietta”.

Following the Civil War, in 1866, Thomas W. Patton, left the complicated settlement of the estates of his father, James. W. Patton and his brothers in the hands of the family lawyer, Nicholas Woodfin, and moved to Alabama, to operate two cotton farms, one which had been given to him by the aunt of his wife Annabelle Beatty Pearson (whom he had married in 1862 in Greensboro, Alabama), and the adjacent farm which he had inherited from his father, James W. Patton. But according to his official biography, due to a number of vicissitudes, including labor troubles navigating from slave labor to paid labor, a crop failure, the death of his wife and child, and finally contracting malaria[14], Thomas handed the one farm back to his wife’s aunt’s family, and returned back to Asheville, where he took occupation with the Patton family lawyer, Nicholas Woodfin to assist in the massive settlement of the Patton estates of his father and brothers.

In an attempt to settle Patton estate and its debts, in 1867 Thomas W. Patton convinced his mother and sister to give up their dower interests in the family home, “Henrietta” and the surrounding property on Beaucatcher Mountain, and for “fee simple” buy a piece of land on “Camp Patton”, a former Army training station in what was then North Asheville.[15] On this piece of land, Thomas built a new home (now 95 Charlotte Street) to house, his mother, his sister and his mother’s sister, and eventually after his marriage in 1871 to Martha Turner, to house he and his family. It was then in 1868, that the Pattons sold “Henrietta” and the Beaucatcher lands (150 acres) to W. D. Rankin.[16] Rankin had moved to Asheville in the 1840’s and had purchased the old George Swain house, just north of the Eagle Hotel and opened it as a supply store. W. D. Rankin had previously (1865) purchased numerous other Patton estate properties, including the old Patton store on the west side of S. Main, which he was operating as Rankin & Son.[17]

According to the written history, “During Bishop Gibbons’ first visit to Asheville in 1868, a vacant space, containing about seven and a half acres in the centre of the town attracted his and the clergy’s attention. A more suitable place for a church and other ecclesiastical building could not be found. It was purchased at a moderate sum from Col. N. A. Woodfin, an eminent lawyer…”.[18] Although this may explain how a Catholic Church first came to be in Asheville, the historian was mis-informed as the land for the site of the church was purchased, not from N. A. Woodfin, but from W. D. Rankin. In August of 1869, Rankin sold 7-3/4 acres of the former 150 acre Patton lands, to the “Rt. Rev. James Gibbons of the City of Wilmington, NC,” for “the use of the Catholic Church”. [19] The property included the “grove on the top of the Hill” just above the east side of what the deed described as “the New street which is to be made, running from the Asheville Female College, down the Valley passing the Tanyard to intersect with the Main Street near Dr. J. F. E. Hardy’s,” which would later be named Valley Street. A few days after the sale, it was announced in the Asheville News, “the beautiful knoll in the rear of the Eagle Hotel has been purchased by Bishop Gibbons, of the Catholic Church, upon which it is intended to erect a fine church edifice.”[20] The Bishop stated that besides “a much larger number of persons holding to the Roman Catholic faith in this vicinity”, the reason for erecting a catholic Church in Asheville was that it “would attract a number of emigrants who would not think of coming if church privileges were not provided.”[21] The Catholic’s soon erected a fine brick church with a Spire and granite foundation, with interior woodwork of heart pine,[22] on top of what would thereafter be known as “Catholic Hill”. They named the new church, “St. Laurence”.

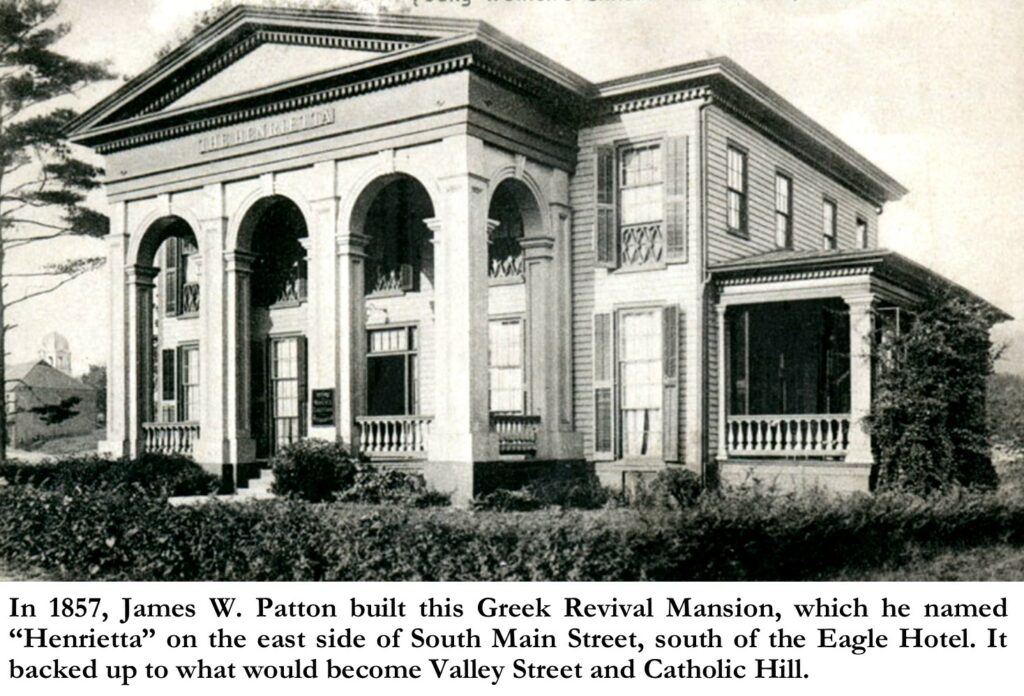

Two years later, in 1871, W. D. Rankin sold an adjacent (to the south) 5-acre property on top of the hill to the Vestry of Trinity Episcopal Church for the establishment of a mission church for the African American community that was starting to formulate in that area. Just after the Civil War ended, Trinity Episcopal Church started a “colored Sunday School” under the direction of Gen. J. G. Martin, which by 1871 had 100 students enrolled.[23] Through money raised by Rev. Jarvis Buxton “from home and abroad”[24], the Vestry erected a wood-frame chapel with a raised basement, for $1,350, on the crest of the hill. The new church was first called “The Chapel for the Colored People of Asheville”[25] but was soon christened as “Trinity Chapel”. The chapel was on the upper floor and the basement level housed a “free Parochial school for colored children”, all of which were in operation by the start 1872. The Sunday School, chapel services, and school were first started by the Trinity Church members, but then in 1874, Rev. S. V. Berry came from Western New York to be the first priest of Trinity Chapel.

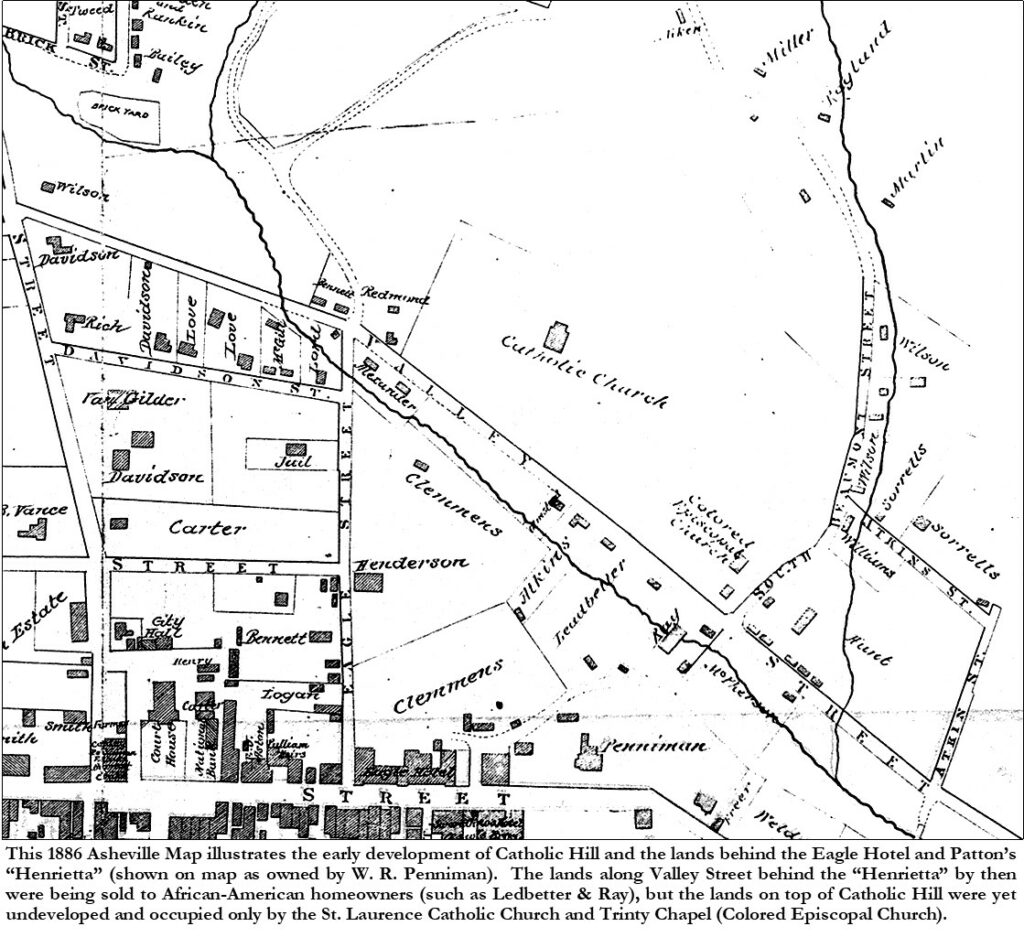

During the Reconstruction Era, the federal government granted the right to vote to African Americans in the South and provided some equal protection to African American citizens. As Reconstruction failed in 1877 the movement for the rights of African American’s stalled. Although the 1875 Civil Rights Act had stated that all races were entitled to equal treatment in public accommodations, the Supreme Court’s Civil Rights Cases of 1883 held that the law did not apply to private persons or corporations. The court made clear that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment provided no guarantee against private segregation.[26] “One of the ironies of Reconstruction,” says modern-day Harvard Historian Henry Louis Gates, in his PBS series on Reconstruction, “is that Black people could claim certain rights in the 1870’s that they would have to fight to reclaim in the 1960’s.”[27] As the 1880’s progressed and “African Americans discovered that they wouldn’t be allowed to cross the color line,” says Gates, “they turned inward and created a Black World within a White World”,[28] creating all Black neighborhoods and even all Black towns. The development of Catholic Hill and the East End neighborhood in Asheville followed this same pattern and timeframe. Throughout the 1870’s and the 1880’s, a small group of African American residents had begun to populate below the hill along Valley Street and north of Catholic Hill along Mountain, Poplar, and College Streets, however Catholic Hill remained unpopulated except for the two churches. But as the 1880’s drew to a close this would take a dramatic turn.

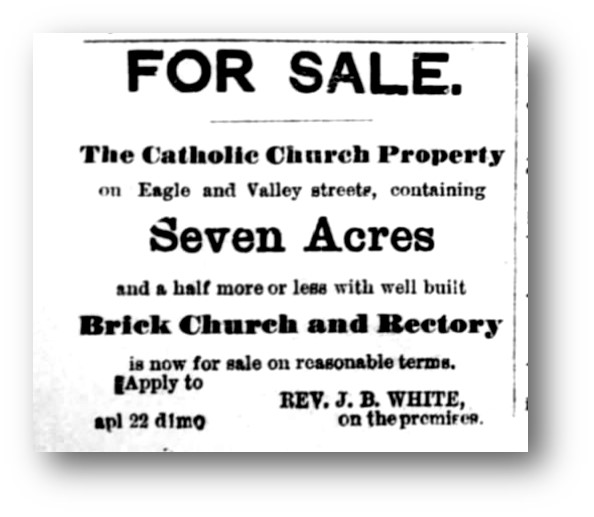

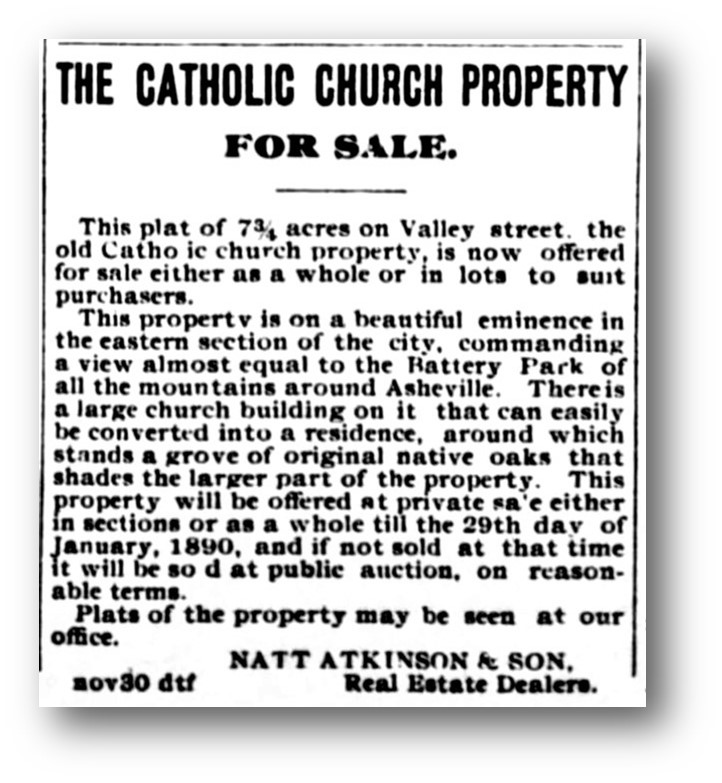

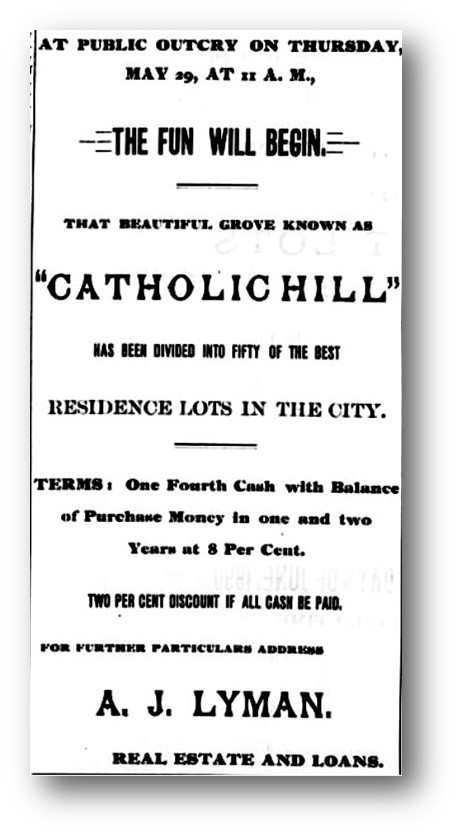

“The old Catholic Church property is for sale. See notice.”, announced the April 22, 1888 edition of the Asheville Citizen Times.[29] The “notice”, also on the same page, read: “For Sale- The Catholic Church property, on Eagle and Valley Streets, containing Seven Acres and a half more or less with well built Brick Church and Rectory- Reasonable terms, Apply to Rev. J. B. White, on the premises.”[30] The Catholic Diocese had already begun plans for building a new Catholic Chapel and Rectory, on a newly purchased site near the corner of Flint and Haywood Street (this was the site of the former parsonage of First Presbyterian Church).[31] Rev. White advertised for the sale of the Catholic Church property until the end of May, and then must have decided that he needed to concentrate his efforts first on the new construction and relocation. He began entertaining bids for the new church during the summer of 1888, as well as also traveling in July to Baltimore to attend the consecration of the Rt. Rev. Leo Haid, the new Bishop-elect of the North Carolina diocese.[32] The new St. Laurence Chapel at the corner of Haywood and Flint Streets was dedicated by Bishop Haid on July 14, 1889. Advertisements for the sale of the now vacant former Catholic Church property resumed in November of 1889. This time Rev. White put the sale into professional hands, turning it over to Real Estate Dealers Natt Atkinson & Son. In true advertising style, the property was enticingly described: “This property is on a beautiful eminence in the eastern section of the city, commanding a view almost equal to the Battery Park of all the mountain around Asheville. There is a large church building on it that can easily be converted into a residence, around which stands a grove of original native oaks that shades the larger part of the property.”[33] Interestingly, the advertisement revealed that the church also had a back-up plan for the sale of the property: “This property will be offered at private sale either in sections or as a whole till the 29th day of January, 1890, and if not sold at that time it will be sold at public auction on reasonable terms.”[34] The advertisements ran until February 1st, 1890,[35] and then the next mention is in the second week of May 1890. It was then announced that St. Laurence Church on Catholic Hill and its surrounding 7-3/4 acre property had been sold to investor James H. Laughran.[36] Laughran (also spelled Loughran) immediately had the property subdivided and platted for 51 lots surrounding the Church (which sat on its own lot marked “Church Reservation”).[37] Laughran was the owner of the “Acme Wine & Liquor House and The White Man’s Bar” on S. Main Street, and was not a professional real estate developer, and clearly he viewed his purchase as an investment opportunity. In two weeks’, time he announced that he would be auctioning off the lots on May 29, 1890. Pre-auction advertisements showed that Laughran was out to make a profit and hence he was appealing not to individual homeowners, but to other investors. Laughran’ s agent A. J. Lyman ran pre-auction advertisements offering terms of “One Fourth Cash with Balance of Purchase Money in one or two Years at 8 percent” with an additional incentive of a “TWO PERCENT DISCOUNT OF ALL CASH BE PAID”.[38] But then in smaller teaser ads on the front pages of the newspapers, Laughran blatantly appealed to speculative investors: “A SAFE INVESTMENT-The valuable property known as “Catholic Hill” offered for sale on Thursday, May 29, is most valuable for a home or as an investment. Be sure to attend the sale in person. There is money in it for you.”[39]

At the May 29th auction, all the lots were sold, most to multiple buyers, who all seemed to be investors who either intended to build a rental-income producing house, or re-sell to an actual homeowner (African American). The subtitle of the article reporting the results of the auction sums it up- “Fifty Per Cent Profit In Two Weeks”-all with little effort by Laughran, the supposed “developer”. [40] None the less within the next few years a few of the lots would be developed along the southside of Catholic Avenue, behind the Church.

However, despite the 1890 auction, the 1891 “Bird’s Eye View of Asheville”, still showed an undeveloped Catholic Hill. Both the Bird’s Eye View and the 1891 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Asheville also showed the “negro tenements” at the southern end of Valley Street, behind the “Henrietta”, just below Catholic Hill. Although we don’t know if the tenements shown were the original Patton slave-quarters or new tenements, it’s highly likely that the site was the site of the original Patton slave-quarters, none-the-less it was clear that an African American community was beginning.

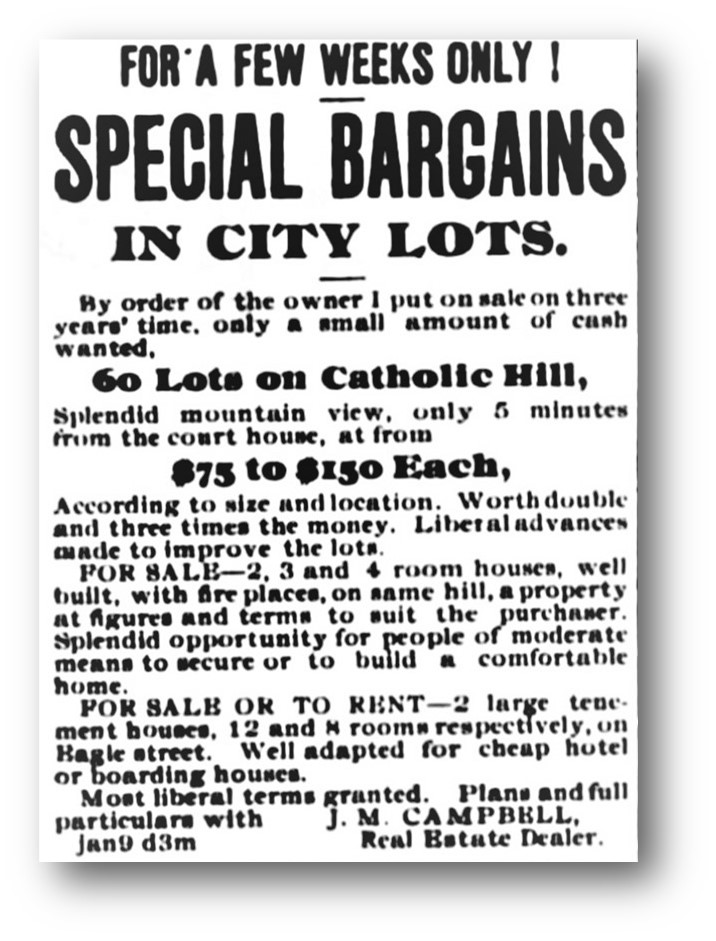

Perhaps spurred by the 1890 sale of the Catholic Church property, concurrent with the advertisements for the sale of the “Catholic Church Property” that were run by Natt Atkinson in the first few months of 1890, beginning in January of 1890, the following advertisements by “Real Estate Dealer” J. M. Campbell began advertising: “For A Few Weeks Only! Special Bargains In City Lots- By order of the Owner I put on sale on three years’ time, only a small amount of cash wanted, 60 Lots On Catholic Hill.”[41] Campbell further described the lots: “Splendid mountain view, only 5 minutes from the court house, at from $75 to $150 Each, According to size and location. Worth double and three times the money. Liberal advances made to improve the lots.”[42] These advertisements ran until the end of April, just before the sale of the Catholic Church property to Laughran, so I had first thought it was the Catholic Church Property, but I don’t think that the church would have had two separate realtors handling it. So, although I have not conclusively established it, I strongly suspect that these lots were part of the Patton Heirs land that the Patton’s still owned surrounding the Catholic Church property, and therefore “the owner” was the Pattons. Although it does not specifically mention it, these lots would have appealed to African Americans as not only were they in an area where an African American presence had been growing, but also the cheap prices, easy terms (three years’ time and “little cash wanted”-low down payment), and the “Liberal advances made to improve the lots”, would have been appealing incentives to African Americans who often had low-paying jobs and little cash. But the most important appeal for African Americans in Asheville at that time, was that it was land that they COULD buy and build a house on in the city, as most of the other developments of the time, sadly, had deed restrictions prohibiting any purchase or sale to any “negro” or person of “African descent”.

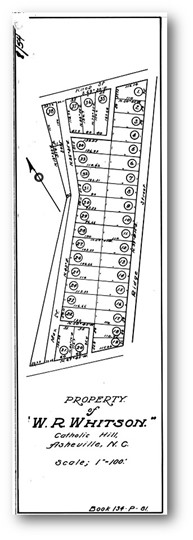

The reason I suspect that the J. M. Campbell advertisements were for the Patton heirs is that shortly thereafter in June of 1891, the Patton heirs teamed up with lawyer W. R. Whitson to develop their property, which was north and east of the Catholic Church property (yet all on top of Catholic Hill). The Pattons’ property included several parcels/tracts. The Patton heirs, represented by Thomas W. Patton retained the northern half of their property, just above the Catholic Church property, which included modern-day Circle, Knob and Pine Streets and had it subdivided in 1901.[43] The Pattons sold the remainder of the property, east and south of the Catholic Church property to W. R. Whitson. The investment nature of this sale was evident in that between 1891-1901, this property was sold back and forth[44] until finally being sold back to W. R. Whitson in 1901, who subsequently had the property subdivided and platted.[45] The Whitson property not only shared its western boundaries with Laughran’s “Catholic Hill Property”, but also included an extension of Grail Street, which was first platted by Laughran. Whitson’s development consisted of 38 lots, most of which were double-loaded between the two north-south streets, Max Street on the west and Ridge Street on the east, with access from Grail Street on the south and Knob Street (that portion, now called Hazzard Street) on the north. It also joined the Patton development on the north.

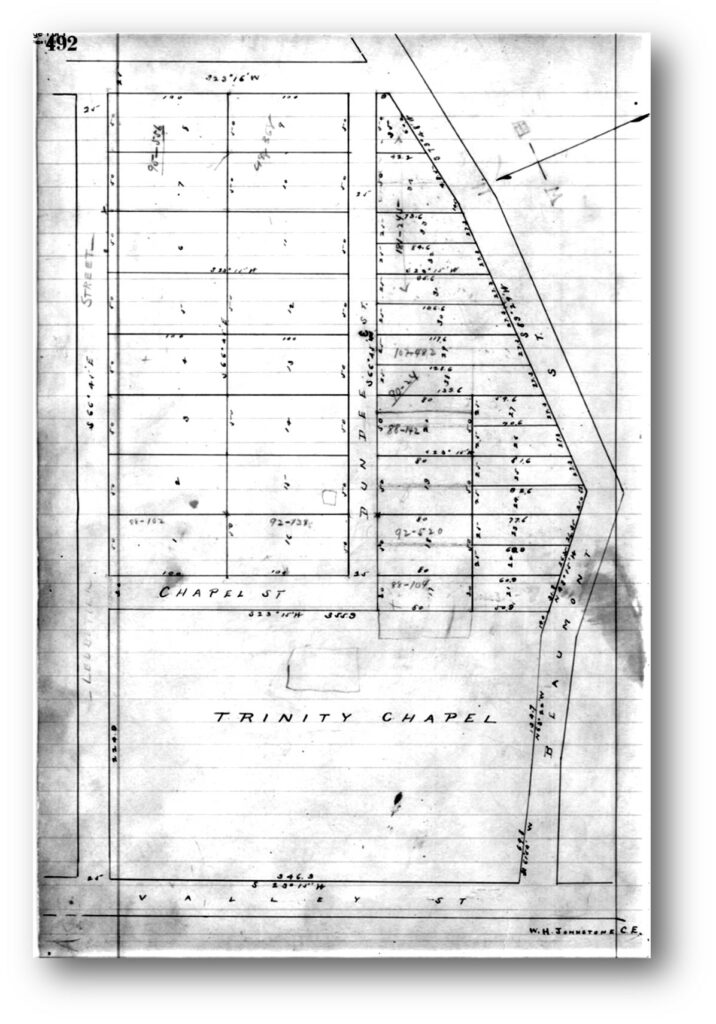

Just as an additional note, to illustrate that Catholic Hill began to rapidly develop soon after the Catholic Church property was sold in 1890. In addition to the Patton heirs’ decision to sell their surrounding parcels for development, Trinity Chapel also decided in 1892 to subdivide and develop their five-acre parcel which they had purchased from W. D. Rankin in 1871. At the time, the Trinity Chapel property was owned by Trinity Episcopal Church. A parcel at the front of the property (west side) was reserved for Trinity Chapel and its later (1894) new church, St. Matthias, and the remainder of the property was subdivided into lots.[46] The lots were double loaded on each side of a center street named Dundee. The northern lots fronted on Ledbetter (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive) and the southern lots fronted on South Beaumont Street, while the center lots fronted on both sides of Dundee Street. Of the four developments on Catholic Hill (Laughran, Pattons, Whitson, & Trinity Chapel), Trinity’s seemed to be the slowest to develop.

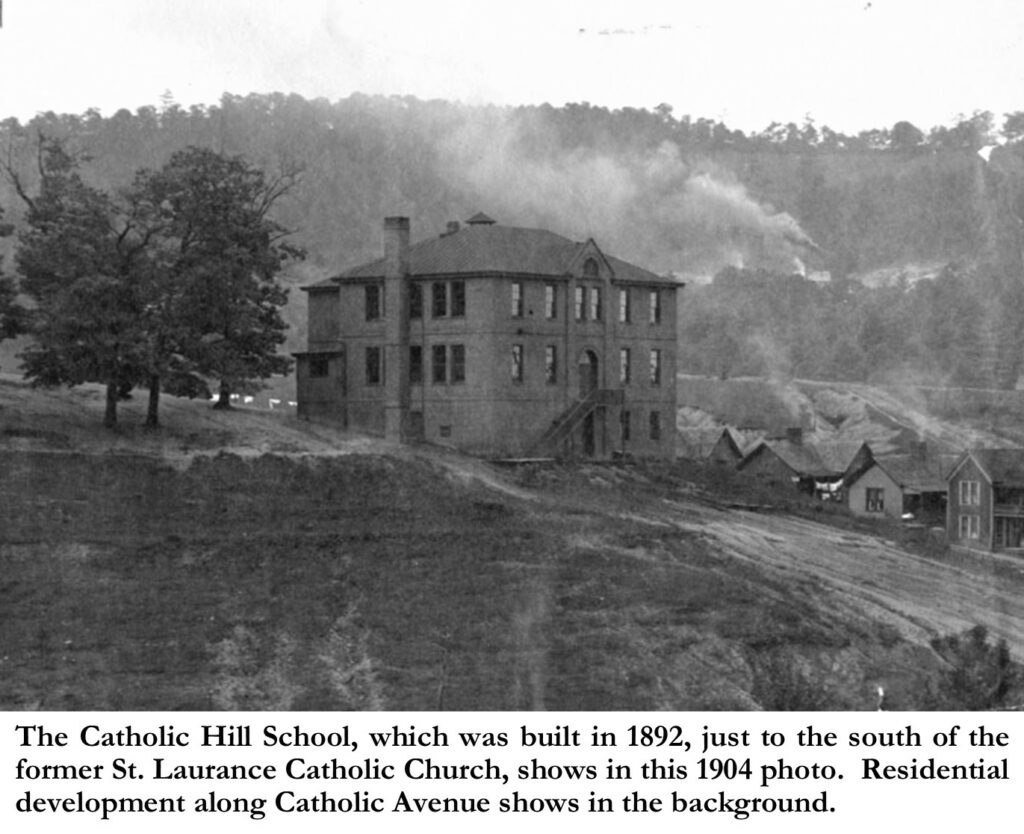

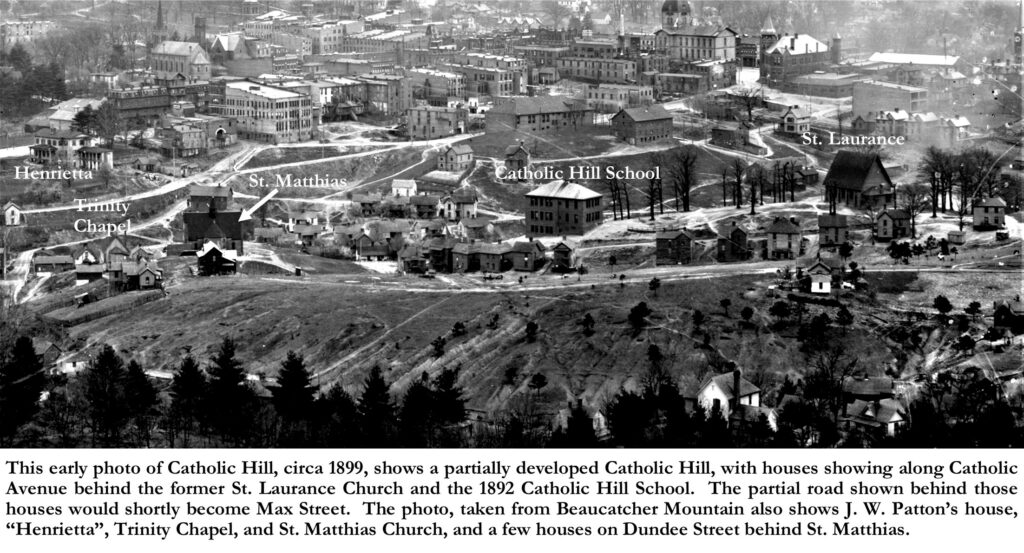

Even further evidence of Catholic Hill, by the 1890’s, rapidly developing into an African American community (or at least as an extension of the East End community) was the building of the Catholic Hill School in 1892. As mentioned earlier, the area north of Catholic Hill, around Poplar, Hildebrand, College, and Mountain Streets had already been growing as a distinctly African American neighborhood, starting in the 1870’s with the establishment of the “colored” school, called Beaumont Academy, which had started in the 1870’s as a county school, but then acquired by the Asheville City School Committee and opened in 1888 as the Mountain Street School. But by 1891, the small one and a-half story frame Mountain Street School was already proving insufficient to handle the increasing population in the growing African- American community in East Asheville. In 1892, the Asheville City school committee announced their decision to build two new public schools, “one on the corner of Bailey and Silver streets, for white children, and one on Catholic Hill for the colored children”.[47] The committee chose to construct the Catholic Hill school first, and entertained bids in March of 1892. The bids were opened on March 15th and the contract for construction was awarded to contractors Joyner and Leonard.[48] Construction began a few weeks later, with completion of the two-story brick school being finished by August of 1892, in time for a September opening.[49]

Now back to the Whitson development. Although the plat for the Whitson property was not recorded until 1903, it was clearly prepared in 1901, as the deeds for the first lot sales in 1901, referenced the plat. The lot sales were spread out mostly on Ridge and Max (up until the 1980’s, this street was sometimes also called Mack Street). All the lots sold to African American owners, and all as residential lots, at first. But then in 1909, W. R. Whitson sold Lot #22, just north of the intersection of Grail and Max Streets, to the Trustees of the “Fire Baptized Holiness Church”, for one hundred and sixty dollars.[50] This “Fire-Baptized Holiness Church” had formed three years earlier. In the 1906 and 1907 Asheville City Directories, a church called “Capadocia Holiness” is listed between 12 and 19 Catholic Avenue, “near Haid”. In 1907, the church purchased a lot just north of the Whitson development on Circle Street, in the Patton development, but apparently it proved insufficient and so they sold it a few months later (December 1907).[51] I don’t believe that the church had built a building on the Circle Street site, and that they continued to meet at the Catholic Avenue location (probably a house or leased building) until purchasing the site on Max Street in 1909.

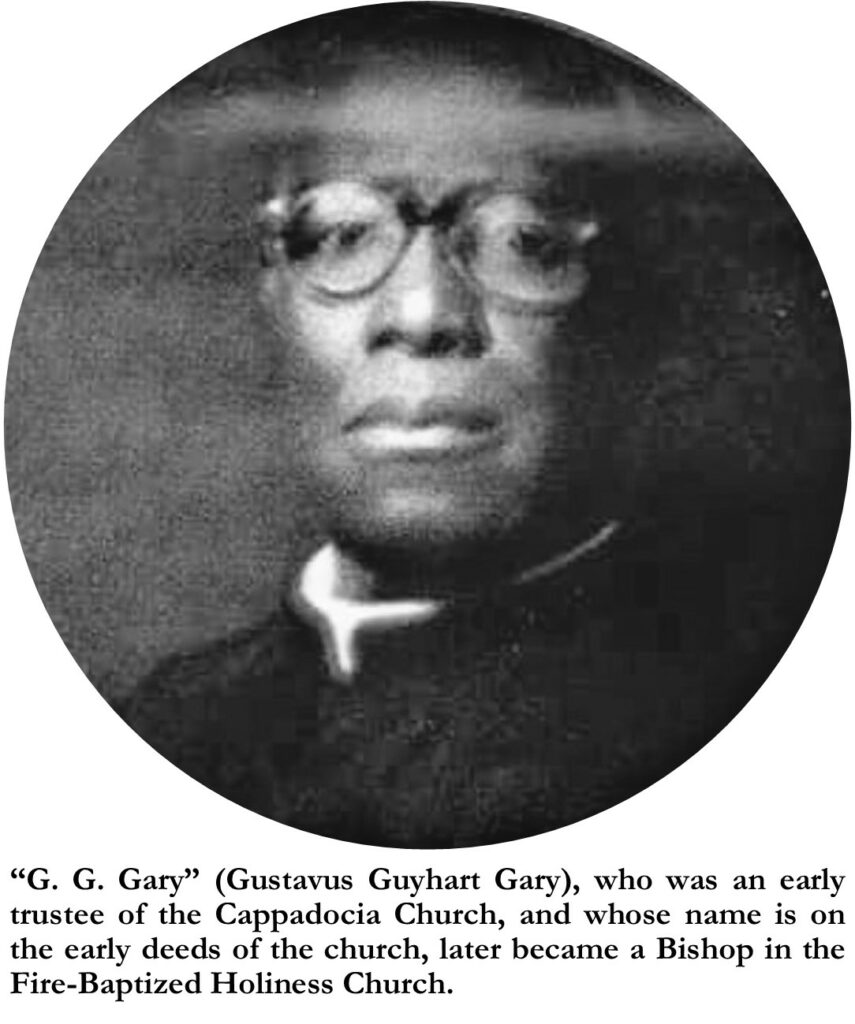

We know that the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church was formed by 1907, as “G. G. Gary”, who was a trustee whose name is on the early deeds of the church and who later became a Bishop in the Fire-Baptistized Holiness Church, recorded in a memoir that: “He accepted Christ in the beauty of holiness under the preaching of the late Bishop W.E. Fuller Sr. on March 10, 1907 at Cappadocia FBH Church in Asheville, North Carolina.”[52] Gustavus G. Gary was not only confirmed as a deacon that same year, but in 1909 he was called into the ministry; with his First Charge being in Old Fort, North Carolina, and then during the same year he was sent to pastor Antioch FBH in Knoxville, Tennessee.[53] In 1958, Rev. G. G. Gary was elected Bishop in the F. B. H. Church of a Diocese comprised of 4 Districts: New York, New England, South Carolina #2, and Alabama, and later Southeast Georgia.[54]

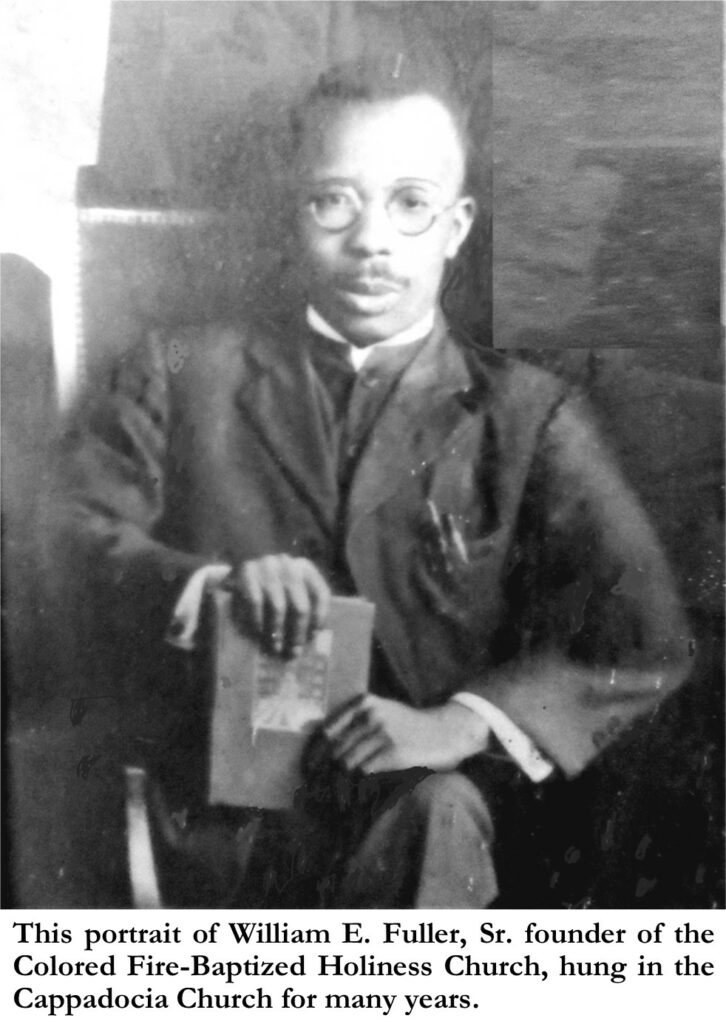

The “Fire Baptized Holiness Church” on Catholic Hill was more specifically called the “Cappadocia Holiness Church” or more correctly, the Cappadocia Fire-Baptized Holiness Church of God” and was first affiliated with the Fire-Baptized Holiness Association. The Fire-Baptized Holiness Association had originated in Iowa in 1895 under the leadership of Benjamin H. Irwin of Lincoln, Nebraska. Irwin expanded this into a national organization as the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church at Anderson, South Carolina in August 1898. At age 23, William E. Fuller, Sr., a member of the African American New Hope Methodist Church, attended the founding of that body in 1898, where he saw Blacks and whites admitted with equality. Following the 1898 meeting, William E. Fuller resigned his offices, turned in his license, and cast his lot with the Fire-Baptized Holiness. After Irwin left the church in 1900, Joseph Hillary King became the general overseer. Fuller served as Assistant General Overseer to King in 1905. Acting on what he thought was a trend toward segregation, in 1908, Fuller led about 500 members to organize the Colored Fire Baptized Holiness Church in Greer, South Carolina. On June 8, 1926 the name Fire Baptized Holiness Church of God of the Americas was adopted by the denomination.[55] Cappadocia F. B. H. Church, as it was most recently called, according to a 1926 Deed of Trust[56], was originally named the “Fire-Baptized Holiness Church of America”, then the name of the church was changed to be the “Fire-Baptized Holiness Church of Asheville, North Carolina”, and later by unanimous consent of the congregation and trustees of the church, the name of the said church was changed to be the “Fire-Baptized Holiness Church of the Americas”, affiliated with the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church of the Americas, Incorporated denomination headquartered in Greenville, SC.

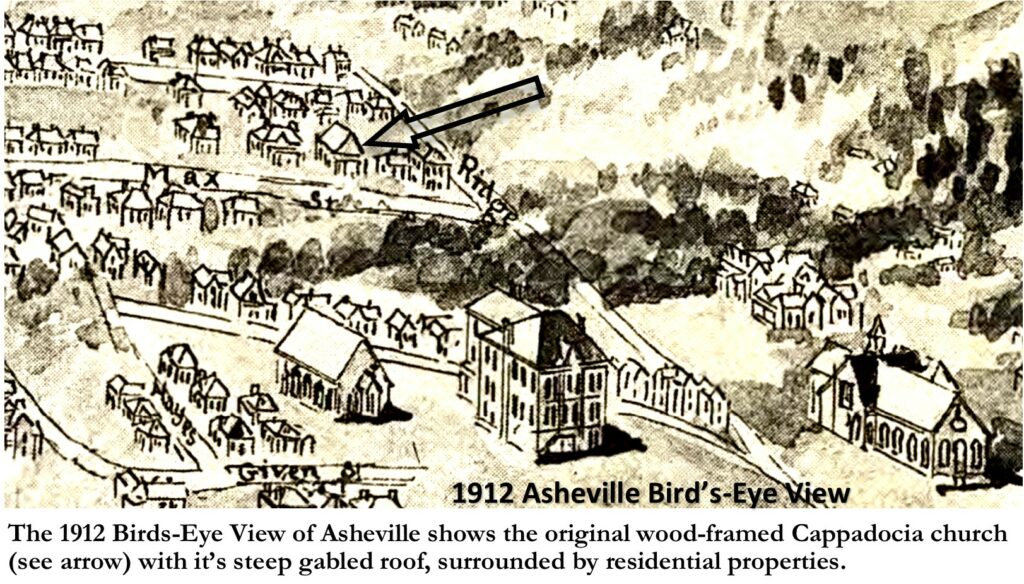

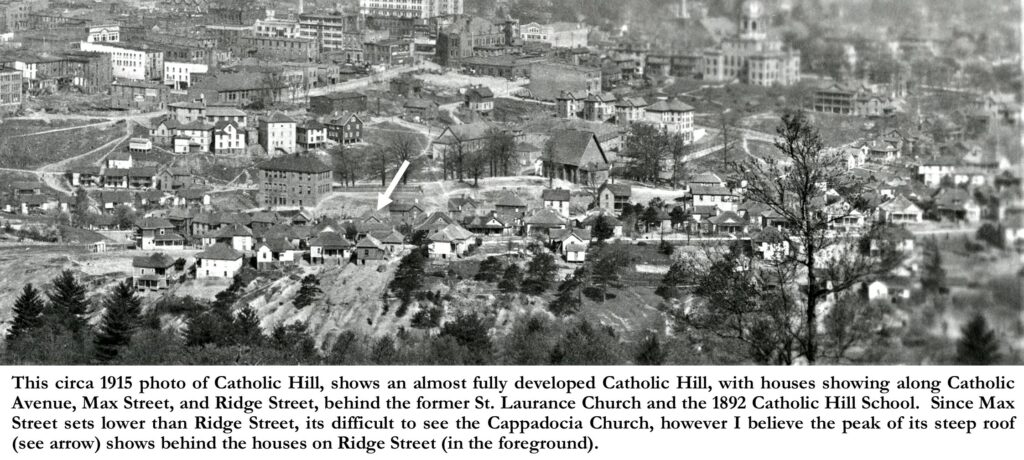

When the Cappadocia Church bought their site from W. R. Whitson in 1909, according to the Asheville City Directory, Max Street only had two residents, and was noted as being located “south from 6 Knob Street”, indicating that it was only accessed from the north instead of from Grail Street on the south. In fact, Grail Street does even not show in the 1909 Directory. However, by 1910 the City Directory showed that Max Street had six houses and the “Fire- Baptized Holiness Church” on it. Also, in 1910, the City of Asheville announced the “construction of a sewer line known as section No. 3 on Grail, Ridge, Max and Haid Streets”, so we know that those streets were starting to open up for development. From other evidence, it appears that shortly after purchasing their lot, that the Cappadocia Church had erected a one-story frame building, with 16 foot high walls, and a small centered one-story entrance portico.[57] In July of 1909, the Cappadocia Church trustees, signed a deed of trust to J. E. Rankin to hold a note payable to contractor P. E. Lingle for $301, with the church agreeing to pay ten dollars a month on the note until it was paid off.[58] This note was apparently only part of the financing, as we know from a later report that the cost of construction was actually $695. [59] One note: the cornerstone on the existing church gives the original date of construction as 1908. I guess there’s a possibility that construction may have begun in 1908 before the sale of the lot was finalized, however, I believe that the construction began in 1909. The 1912 Birds-Eye View of Asheville shows the original wood-framed Cappadocia church with it’s steep gabled roof, surrounded by residential properties.

When the church was built, the pastor was Rev. William Chappell, who lived at 27 Circle Street (but NOT on the lot purchased in 1907 by the church). Chappell’s name is on the early deeds and deeds of trust. Prior to Chappell, in 1906 and 1907, Rev. Earlie (Earl J.) Dodson was listed as the pastor. In 1910, the city directory listed “Rev. Lee”, as the pastor of the “Fire Baptist Holiness Church”, which appears to have been Walter S. Lee who was also the principal of the Catholic Hill School. I suspect that Lee was functioning as an interim pastor, as that’s the only year he is listed as pastor. The next pastor that I could find listed was Rev. George W. Bennett. Oddly however, in the 1913 directory, Bennett is listed as the pastor of the “Macedonia Sanctified Church” at 59 Max Street! Then in the 1914 directory, Rev. George W. Bennett was listed twice, as the pastor of the Macedonia Sanctified Church at 59 Max Street, but elsewhere in the same directory he was listed as the pastor of the “Fire Baptize Holiness Church”. This conundrum continued into the 1914 Directory, and then into the 1916 directory, although by then Rev. George W. Bennett had gone back to being a carpenter, and a Rev. G. C. Curry had assumed the pastorate of the “Macedonia Sanctified Church” at 59 Max Street. The following year, the 1917 directory listed Rev. Uzmon Bobo as the pastor of the Macedonia Sanctified Church at 59 Max Street. But then to add further confusion to the conundrum, in the 1918 directory, Rev. Uzmon Bobo, who was living 44 Ridge Street, just around block from the church, is listed both as the pastor of the “Capadocia Holiness Church” at 57 Max Street AND of the “Macedonia Sanctified Church” at 59 Max Street. Were there two congregations meeting in the same building, as 57 and 59 Max Street are the same address for that lot? Perhaps that was the case, but I suspect that perhaps the church was renamed in 1913 by Rev. George Bennett, but not officially and so for a few years it was known as either name. However, I can’t substantiate my suspicion as the church name does not appear again in the city directories until the 1923 directory where it is listed as the “Cappadocia Baptist Church”, with Rev. Wm. Adams (who lived next door at 61 Max) listed as the pastor. From that time on, there ceases to be any references to the name “Macedonia Sanctified Church”, with the church settling on the name “Cappadocia”.

Speaking of the name “Cappadocia”, where does it come from and why did the church select that as their name? Both the name Cappadocia and “Fire-Baptized” come from the Bible, from the Book of Acts where the writer recounts the events of the day of Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit was sent by God to indwell the new believers meeting at Jerusalem:

“And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place. And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance.”[60]

Many Christians believe that Pentecost was an extraordinary circumstance, given to those first believers to spread the message of Jesus to world, but that since then, everyone who comes to faith in Jesus is baptized (indwelled by) in the Holy Spirit upon conversion. However, the “Fire-Baptists”, and those of the “Holiness” and Pentecostal movements believe that there is an experience beyond sanctification called the “baptism with the Holy Ghost and fire” or simply “the fire”, as a “third blessing” at which time believers receive the “gift of tongues”.

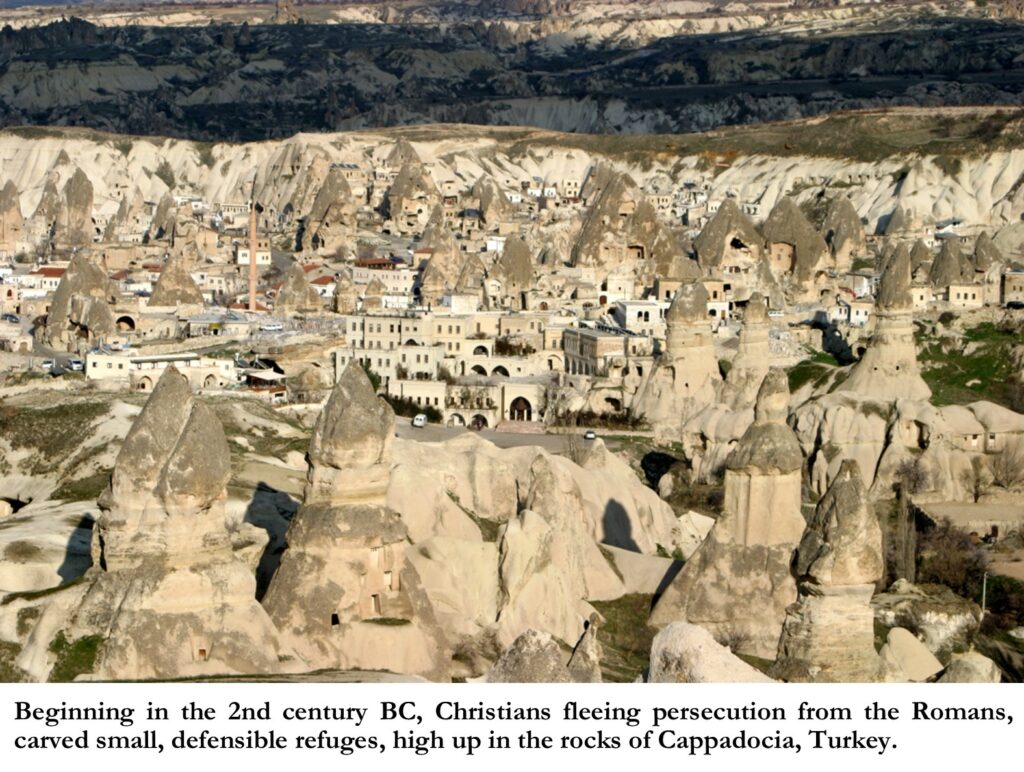

The passage in the book of Acts further describes that at the day of Pentecost, when the first believers started speaking “in tongues” that the cosmopolitan onlookers recognized that “every man heard them speak in his own language.”[61] It was recorded that among those onlookers who heard the believers’ words in their own language were those who hailed from Cappadocia, a region in the country of Turkey. But why did the Holiness church at Asheville choose the name Cappadocia over the several other regions recorded as being represented in the crowd at the day of Pentecost? Well, I can’t profess to knowing why they chose that name, but perhaps those early founders of the Cappadocia Fire-Baptized Holiness Church, had read about the early “churches” and dwellings of Cappadocia, Turkey, which were then being rediscovered by French Jesuit Guillaume De Jerphanion. The ancient region of Cappadocia lies in central Anatolia, between the cities of Nevsehir, Kayseri and Nigde. Cappadocia has one of the most fantastic landscapes in the world. Wind and weather have eroded the soft volcanic rock into hundreds of strangely shaped pillars, cones and “fairy chimneys”, often very tall, and in every shade from pink through yellow to russet brown. Beginning in the 2nd century BC, Christians fleeing persecution from the Romans, carved small, defensible refuges, high up in the rocks. Father Guillaume de Jerphanion, who made his first excursion to Cappadocia in 1907, published the following year a brief description of the churches of the area according to plan –types.[62] Although it’s doubtful that the founders of the Asheville church were aware of or had read Jerphanion’s report, it is possible that they had read the widely published newspaper reports of the new discoveries in Cappadocia. One article that was published in numerous newspapers across the US in 1908, was titled: “ODD CONE PYRAMIDS-STRANGE DWELLING PLACES OF THE PEOPLE OF CAPPADOCIA.”[63] Perhaps the founders of the church at Asheville identified their church as, like the cave dwellings of early Christians of Cappadocia, a place of refuge on the hill, that is Catholic Hill.

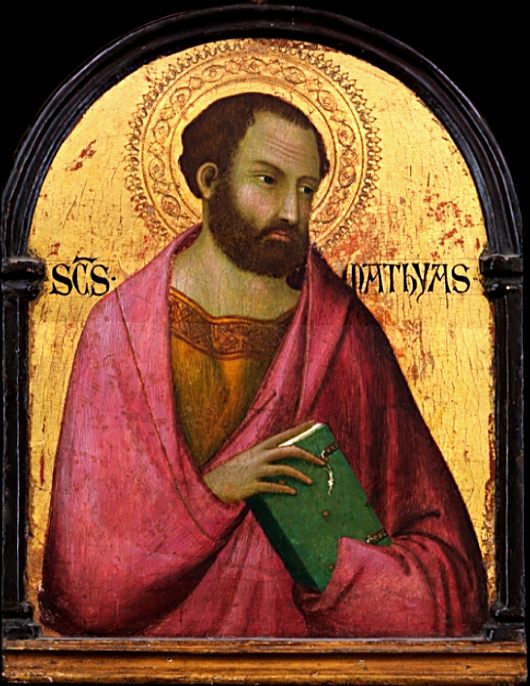

One additional explanation for the choosing of the name Cappadocia, is that perhaps the founders of the church at Asheville knew of the tradition of St. Matthias, who according to various traditions, preached in Cappadocia, Jerusalem, the shores of the Caspian Sea (in modern day Georgia) and Ethiopia. This is a probable explanation as Cappadocia’s neighboring church on Catholic Hill, the former Trinity Chapel was rebuilt and renamed “St. Matthias” in 1894, indicating that the tradition of St. Matthias was well known among the local Black clergy. If the traditions of St. Matthias were true, then it would be doubly appropriate for the church to adopt the name Cappadocia, as its association with St. Matthias means that Matthias had not only been a missionary to Ethiopia, but also had ministered among some of those in Cappadocia who may have witnessed the “fire-baptism” at the day of Pentecost.

Nonetheless, by 1924, the Holiness church on Catholic Hill had not only settled on Cappadocia as its “first” name but had hired Rev. Walter S. Barbour as their pastor. Under his leadership, the church began to grow so much that at a congregational meeting held on September 8, 1925,[64] the congregation authorized the church trustees (C. H. Hunter, R. B. Hatten; A C Smith, Moses Woods, and Mack Goodman) to borrow $7,000 in order “to construct a new church or remodel the present church.”[65] The trustees decided to rebuild the existing frame church. Looking at the Sanborn Maps, it appears that the rebuilding included removing the front one-story entrance (or possibility just building around it) and building on each side and above it, extending the church to the front. This included a second-floor balcony across the entire front, and a new stair to the basement from the front interior entrance stair landing. I believe this was probably when the basement was dug out at the front for use of as restrooms, kitchen, and fellowship hall. The most noticeable changes made in the 1926 renovation were the addition of the flanking towers at the front, and the brick veneer which was attached to the exterior of the existing wood framing. Rev. W. A. Barbour soon after the renovation opened a “Negro School” (also called the “Fire-Baptized Holiness School”) at the church, which in 1928 was recorded as having 50 students.[66] Barbour continued to pastor the church through the early days of the depression, perhaps due to the Great Depression, Rev. W. A. Barbour established the “New Way Cleaning” business at 98 Eagle Street.[67]

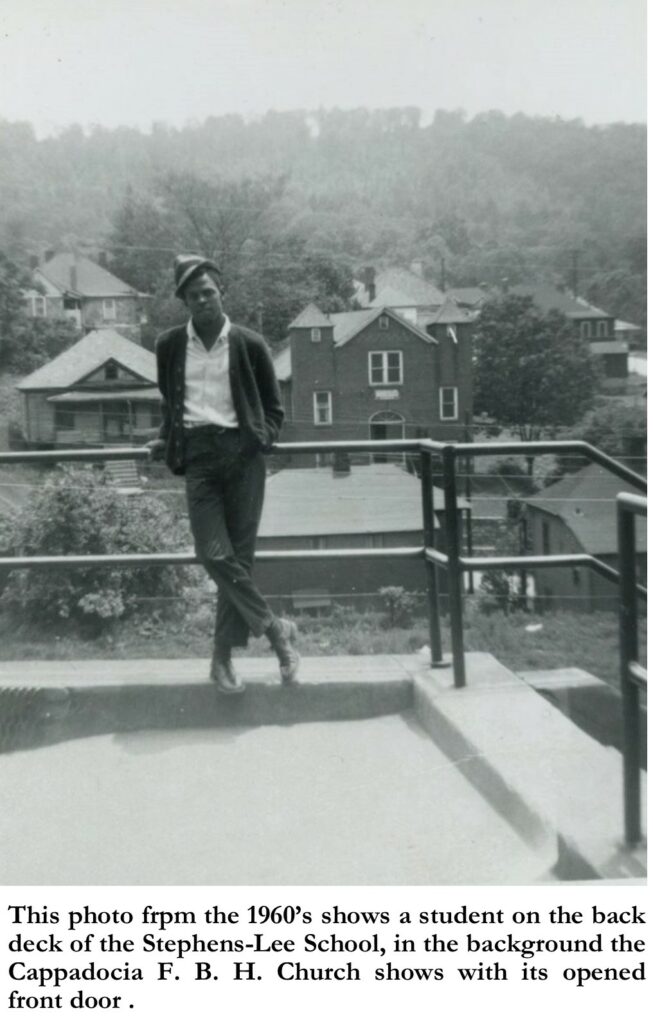

Beginning in 1931 the church seemed to switch pastors about every year or year and a half, however it continued to serve as a part of the Catholic Hill/East End community on throughout the whole of the twentieth century. A photo from the 1960’s shows a student on the back deck of the Stephens-Lee School, and in the background is the Cappadocia F. B. H. Church with its opened front door, inviting all to enter. The Stephens-Lee School had replaced the old Catholic Hill school which had been tragically destroyed by fire in 1917.

By the 1970’s the Catholic Hill neighborhood, and in fact all of the East End neighborhood, was showing signs of dilapidation and therefore was targeted for “urban renewal”. On April 5, 1978, an 11.4-million-dollar project, named the East End-Valley Street community improvement plan” was finally approved by the Asheville City Council.[68] Lawrence Holt, deputy director of the Asheville Housing Authority, reported that the area was “one of the last to receive public services and utilities.”[69] Not surprisingly, Holt further reported that “of the 430 structures in the area, only 29 meet the city housing code and 219 are dilapidated”.[70] According to Holt the “improvement plan calls for considerable housing rehabilitation and demolition.”, however he also stated that he “estimated that 100 structures in the area will not be replaced”. Obviously, that meant that the project included little “housing rehabilitation” and was mostly about demolition of the remaining 330 structures”. Obviously, the Asheville City Planners had not read, or at least disregarded activist, Jane Jacobs’ groundbreaking book of 1961, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, where Jacobs argued that “urban renewal” and “slum clearance” did not respect the needs of city-dwellers. And in fact, as the Asheville East End “Improvement” Project progressed through the late 1970’s and on into the mid 1980’s, Jacobs would prove to be right as according to UNCA history professor Sarah Judson in a 2014 article in The North Carolina Historical Review, “by 1982, Valley Street, the historic root of the neighborhood, was gone, redirected, and renamed South Charlotte Street after Charlotte Patton, a member of the prominent Asheville slaveholding family. Pathways that interconnected lives and destinations were paved over to make municipal garages and administration buildings. People who had lived in the dense housing of the neighborhood found themselves in public housing communities or in far-flung neighborhoods, away from those important networks of support.”[71]

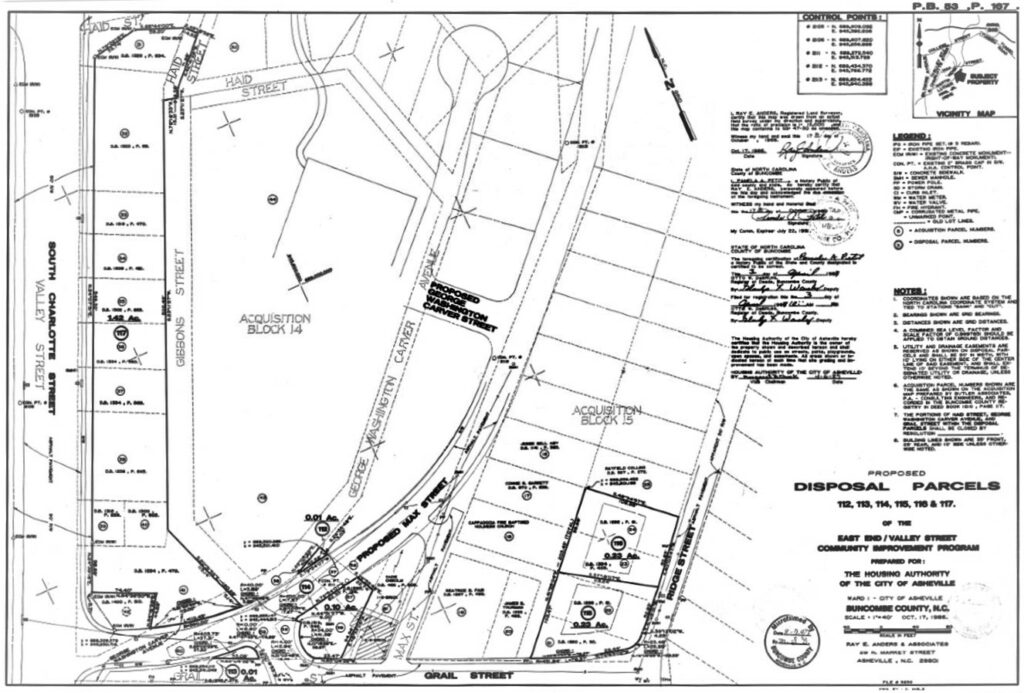

A look at the plats for the “East End/Valley Street Community Improvement Program” show the extent of the demolition and displacement. A 1987 plat[72] of the Catholic Hill area shows specifically that the redevelopment significantly impacted the Catholic Hill neighborhoods. By then, the Stephens-Lee school, on top of Catholic Hill, which had not survived the desegregation of the schools, had closed, and been demolished, leaving only the gymnasium annex. The plat was tellingly titled: “Disposal Parcels” and showed the disposal of four lots on northside of Ridge street at the corner of Grail Street. But the major change that shows on the plat is the rerouting of Max Street. Instead of Max Street starting at Grail Street, it was rerouted to come directly off the new “S. Charlotte Street” (which basically followed the old Valley Street) and then following what was Catholic Avenue, Max Street was rerouted in a sweeping turn to connect to the upper east end of the old Max Street, although even that end was straightened. To achieve this new “improved” Max Street, all the houses on the north side of Max Street, as well as all the houses on Catholic Avenue had to be demolished. An odd result was that the rerouted Max Street left the Cappadocia Church property abandoned, necessitating the retention of a short section of the old street for access to the church property. The short street was appropriately renamed, “old Max Street”. Fortunately, most of the houses on the south side of Max and their neighbors along Ridge Street to the south survived the redevelopment leaving most of the block as it was originally built.

Although the Cappadocia Church managed to survive the urban renewal project of the 1970’s and 80s, the break-up of the community seemed to have affected the growth of the church and judging by the numerous obituaries that I’ve found referencing the deaths of church members, it’s obvious that the membership of the aging congregation began to dwindle. According to Jesse Pulley, one of the last surviving church members, by 2013, the congregation had dwindled to only four members. Pulley himself had to finance many of the improvements in the last years, such as the new carpet, insulation, and furnace repairs just to keep the church building from dilapidation. But alas the church was officially closed in 2013.

The church property and its adjacent lot at 55 Max Street, which had been sold to the church in 1993,[73] remained vacant from 2013 to 2021. In the Fall of 2021, a developer purchased the church property, as well as the adjacent lot at 61 Max Street, and the house and lot at 32 Grail Street. The developer, of the Max Street properties, had intended to demolish the church and house (at 32 Grail Street) and use the four lots for a multi-family infill project. In an example of how preservation and development can coincide and even cooperate with each other, the developer was willing to sell the church and existing residence at 32 Grail Street to the Preservation Society for rehab/restoration, while retaining the vacant lots for the developer’s infill development. The Preservation Society hopes to rehab the church and the residence into affordable housing options, thereby not only achieving its goal of historic preservation but also meeting the urgent need for affordable housing options in Asheville.

The Catholic Hill neighborhood surrounding the Cappadocia Fire-Baptized Holiness Church was a once vibrant community, but despite its devastating decline and destruction, the Catholic Hill neighborhoods are beginning to regrow into a diverse and vibrant community. The Preservation Society endeavors to help both preserve and revitalize the East End community echoing the motto of the “East End/Valley Street Neighborhood Association”, which boldly claims, “The East End Is Rising!”[74]

Image Credits: (Note: All captions by author)

Cappadocia F. B. H. Church front view- photo by Dale W. Slusser

Composite Surveys- from Old Buncombe County Genealogical Society, 128 Bingham Rd # 950, Asheville, NC 28806.

Eagle Hotel- Image ID C435-8, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Henrietta House– Image ID K662-S, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Trinity Chapel– A Brief History of St. Matthias’ Episcopal Church, Asheville, NC : Celebrating 150 years of Work in Ministry and Service, by the Rev. Jim Abbott. Asheville, NC, 2016, page 28.

Catholic Hill 1886 Map– Image ID MAP-200, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Catholic Church Property -Rev. J. B. White Advert.- Asheville Citizen-Times, November 30, 1889, page 4.

Catholic Church Property Natt Atkinson & Son Advert.- Asheville Citizen-Times, November 30, 1889, page 4.

Catholic Hill Property Auction -A. J. Lyman Advert.- Asheville Citizen-Times, May 26, 1890, page 4.

Catholic Hill Property Plat- 06/01/1890 CATHOLIC HILL PLAT VALLEY GIBBONS GRAILSTREETS CATHOLIC AVE, Db. 8/10 & Db. 70/602- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

1891 Birds-Eye View of Asheville- Ruger & Stoner, and Burleigh Litho. bird’s-eye view of the city of Asheville, North Carolina. [Madison, Wis, 1891] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694894/.

J.M. Campbell Advert.- Asheville Citizen-Times, January 9, 1890, page 1.

W. R. Whitson Plat-11/01/1903 W. R. Whitson PLAT CATHOLIC HILL Db. 8/54.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Trinity Chapel Plat-12/14/1892 TRINITY CHAPEL PLAT-Db. 83/492.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Catholic Hill School- Image ID MS273.001ZH, Asheville The Mountain City In The Land of The Sky Illustrated 1904 Photograph Album, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

G.G. Gary Portrait- True Witness, 2017, page 16, – https://www.fbhchurch.org/publications/truewitness2017.pdf

W. E. Fuller, Sr. Portrait- photo taken by Dale W. Slusser of portrait in the Cappadocia Church.

Catholic Hill from Beaucatcher-c.1899- Image ID A218-N600, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC. Cropped by author.

1912 Birds-Eye View of Asheville- Fowler, T. M, and Charles Hart Litho. Asheville, Buncombe Co. N. Passaic, N.J, 1912. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694896/.

Catholic Hill from Beaucatcher-c.1915- Image ID A228-8, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC. Cropped by author.

Cappadocia, Turkey – Cappadocia in Turkey.jpg.-(2020, October 30). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Retrieved 21:06, December 30, 2021 from- https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Cappadocia_in_Turkey.jpg&oldid=507381115.

Saint Matthias- File:Saint Matthias.PNG. (2018, May 25). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Retrieved 21:18, December 30, 2021 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Saint_Matthias.PNG&oldid=302995203.

View of Cappadocia Behind Student at Stephens-Lee– Image ID L510-DS, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC. Cropped by author.

1987 East End Improvement Plat-04/07/1987 HOUSING AUTHORITY CITY OF ASHEVILLE- PLAT EAST END VALLEY ST COMMUNITY IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM PARCELS 112-117, Db. 53/167.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Cappadocia Church from 1944 Stephens-Lee yearbook- Image ID O268-DSa, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC. Cropped by author.

[1] Darin J. Waters is the Executive Director of the UNC Asheville Office of Community Engagement, an Associate Professor of History, and as the Co-Host of the Waters and Harvey Radio Show and Podcast. https://www.darinwaters.com/

[2] Waters, Darin J. “Life Beneath The Veneer: The Black Community In Asheville, North Carolina From 1793 to 1900”. University of

North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2012. https://doi.org/10.17615/bte1-j211

[3] 04/27/1807 (rec’d-09/30/1807) John Patton to Patton & Erwin 36 ACRES Db. A, page 403.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[4] 10/21/1799 John Strother to Andrew Erwin 180 ACRES Db. 3, page 210.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[5] Asheville and Buncombe County, by Forster Alexander Sondley, edited by Theodore Fulton Davidson. (Asheville, NC: Citizen Company, 1922), Chapter VI, “Asheville”, page 70.

[6] Old Buncombe County Genealogical Society, 128 Bingham Rd., Ste. 950, Asheville, NC 28806.

[7] “Who Were The Builders Up of Asheville”, Asheville Weekly Citizen, January 7, 1875, page 2. The article was signed by “McD”.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Asheville and Buncombe County, by Forster Alexander Sondley, edited by Theodore Fulton Davidson. (Asheville, NC: Citizen Company, 1922), Chapter XI, “Early Customs in Buncombe”, page 144.

[10] From a Buncombe County Special Collections blog titled: Patton Family Online Exhibit, Friday, November 01, 2013. https://specialcollections.buncombecounty.org/2013/11/01/patton-family-online-exhibit/

[11] “The Biography of James Patton”, by James Patton, July 6th, 1844, pages 16-17. Electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South, or the Southern Experience in 19th-century America. https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/patton/patton.html

[12] “Who Were The Builders Up of Asheville”, Asheville Weekly Citizen, January 7, 1875, page 2. The article was signed by “McD”.

[13] James W. Patton had four sons, two of them named Thomas Walton Patton. There were two children of James Washington Patton named “Thomas Walton Patton”, they were half-brothers. –Thomas Walton Patton (I)- born-August 1832 died October 10, 1840– born to James W. Patton (1803-1861) and wife Jane Clarissa Walton Patton (1809-May 1837) & Thomas Walton Patton (II)- born May 8, 1841– died– Nov 6, 1907 – born to James W. Patton (1803-1861) and Henrietta Kerr Patton (1805-1890). Thomas Walton Patton (II) was named for his younger brother who died the year of his birth.

[14] Thomas Walton Patton, Born May 8th, 1841, Died November 6th, 1907: a Biographical Sketch. [United States: Asheville, NC, 1908.], page 15.

[15] Ibid, page 16.

[16] 05/28/1868 (rec’d-08/03/1871) N. W. Woodfin, Attny, & Fannie L. Patton to W. D. Rankin 150 ACRES TOWN MOUNTAIN, Db. 34 / 236.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[17] Advertisement: Asheville Weekly Citizen, Asheville, NC, August 20, 1869, page 4.

[18] A Guide to the History, Art, and Architecture of the Church of St. Lawrence, Asheville, NC, Prepared by the Ladies of the Altar Society, With the approval of the Pastor Rev. Louis Joseph Bour, M. A., Ph. L., 1923, pages 11-12.

[19] 08/13/1869 W. D. Rankin to James Gibbons 7 ACRES ASHEVILLE Db. 29 / 335.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[20] Asheville News, August 20, 1869, page 2.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Weekly Pioneer, Asheville, NC, September 9, 1869, page 2.

[23] Journal of the Fifty-Sixth Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of North Carolina, 1872, page 59.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Journal of the Fifty-Seventh Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of North Carolina, 1873, page 60.

[26] Legal Information Institute, Cornell University- https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/separate_but_equal

[27] RECONSTRUCTION: AMERICA AFTER THE CIVIL WAR, PBS-Public Broadcasting Series- Part 2, Hour 1.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Asheville Citizen-Times, April 22, 1888, page 1.

[30] Ibid.

[31] 04/23/1889 TR First Presbyterian Church to Catholic Church; Rev. Leo Haid HAYWOOD STREET Db. 65/527.

[32] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 29, 1888, page 1.

[33] “THE CATHOLIC CHURCH PROPERTY FOR SALE”- Asheville Citizen-Times, November 30, 1889, page 4.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Asheville Citizen Times, February 1, 1890, page 2.

[36] 05/16/1890 Rev. Leo Haid to James Laughran & D. C. Waddell ASHEVILLE Db. 70/385- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[37] 06/01/1890 CATHOLIC HILL PLAT VALLEY GIBBONS GRAILSTREETS CATHOLIC AVE, Db. 8/10 & Db. 70/602- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[38] Asheville Citizen Times, May 27, 1890, page 4.

[39] Asheville Citizen Times, May 27, 1890, page 1.

[40] “ANOTHER BIG SALE- Catholic Hill Sold At Auction Today-Fifty Per Cent Profit In Two Weeks”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 29, 1890, page 4.

[41] Asheville Citizen Times, January 9, 1890, page 1.

[42] Ibid.

[43] 02/13/1901 T. W. Patton PLAT KNOB & GULLEY STREET Db. 8/53.; 10/30/1901 T. W. Patton PLAT EAGLE & CIRCLE STREETS Db. 8/134. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[44] Here are the sales of the Patton heirs’ Catholic Hill lands between 1891-1901: 09/07/1891 (rec’d-09/10/1891) W. R. Whitson to M. E. & Susie R. Carter COLLEGE-LEDBETTER-RIDGE-BEAUMONT STREET Db. 79/201.; 09/08/1891 M. E. & Susie R. Carter to W. R. Whitson [D/T] Db. 25/576; 08/16/1895 W. R. Whitson/ TR for M. E. & Susie R. Carter to Susannah Hendry (of Philadelphia, PA) LETCHER & LEDBETTER STREETS Db. 94/128. “whereas on September 8th, 1891 M. E. & Susie Carter delivered to the party of the first part…to secure the payment of a note for Five Thousand dollars, payable to T. A. Hendry…”.; 07/11/1901 Susannah Hendry to W. R.

Whitson 2 ACRES LETCHER-LEDBETTER-RIDGE STREETS Db. 117/190. -Buncombe Register of Deeds.

[45] 11/01/1903 W. R. Whitson PLAT CATHOLIC HILL Db. 8/54.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[46] See Plat-12/14/1892 TRINITY CHAPEL PLAT-Db. 83/492.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[47] Asheville Democrat, February 21, 1892, page 1.

[48] Asheville Citizen-Times, March 15, 1892, page 4.

[49] Asheville Democrat, September 18, 1892, page 8.

[50] 10/20/1909 (rec-d-06/05/1913) W. R. & Ida Whitson to Fire Baptized Holiness Church (C. L. Williams, G. G. Gary, W. M. Chappell, Dennis Thomas & Nettie Hunter, Trustees) LOT 22 BK 134 P 81 Db. 185/358. “for the consideration of the sum of one hundred and sixty dollars…”

[51] 04/11/1907 (rec’d-11/19/1907) Lula & Rutherford Little to Fire-Baptized Holiness Church-W. M. Chapel, TR; Nellie Hunter; & C. L. Williams CIRCLE STREET Db. 151/592. “Lot. 10…”; 12/02/1907 Fire-Baptized Holiness Church-W. M. Chapel, TR; Nellie Hunter; & C. L. Williams to W. M. L. Jackson CIRCLE STREET Db. 153/234.

[52] “Bishop Gustavus Guyhart Gary: 1878-1969”, The True Witness, The Official New Magazine of the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church of God of the Americas, Incorporated., Vernell Turner, Editor; Beulah Priest-White Editor, (Greenville, NC, November 2017), page 16.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] For more information see: Encyclopedia of Religion in the South, edited by Samuel S. Hill, Charles H. Lippy, Charles Reagan Wilson (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2005), page 319.

[56] 09/27/1926 C. H. Hunter; R. B. Hatten; A C Smith; Moses Woods; Mack Goodman, Trs Fire-Baptized Church to W H Hipps, TR & Fred Monk [D/T] MAX ST LOT 22 PLAT IN DB 134 PG 81 CORRECTED 9/12/2019 Db. 244/74.

[57] See the 1917 Sanborn Fire Insurance map, Sheet 22. In addition to showing the church as a one-story frame structure, it also indicates that by 1917 the church had electric lights and a stove heater. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3904am.g3904am_g063721917

[58] 08/02/1909 C. L. Williams, G. G. Gary, W. M. Chappell, Dennis Thomas & Nettie Hunter, Trustees to J. E. Rankin & P E Lingle [D/T] Db. 76/381.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[59] “TRUSTEES SEEK TO HAVE TILE CLOUD REMOVED”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 18, 1913, page 1.

[60] Acts 2: 1-5, the Holy Bible, King James Version- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Acts+2&version=KJV

[61] Acts 2: 6, the Holy Bible, King James Version- https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Acts+2&version=KJV

[62] “Tokalı Kilise: Tenth-century Metropolitan Art in Byzantine Cappadocia.” By Ann Wharton Epstein, Annabel Jane Wharton, Paul M. Schwartzbaum. Volume 22 of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, DC, 1986, p. 82.

[63] The Canton-Independent-Sentinel, Canton, PA, October 22, 1908, page 7.

[64] 09/27/1926 C. H. Hunter; R. B. Hatten; A C Smith; Moses Woods; Mack Goodman, Trs Fire-Baptized Church to W H Hipps, TR & Fred Monk [D/T] MAX ST LOT 22 PLAT IN DB 134 PG 81 CORRECTED 9/12/2019 Db. 244/74. “upon unanimous consent of the members and trustees of the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church of America, the name of the said church was changed to be the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church of Asheville, North Carolina, and later by unanimous consent of the congregation and trustees of said church, the name of the said church was changed to be the Fire-Baptized Holiness Church of the Americas…”. “the aforesaid trustees were empowered and authorized to construct a new church or remodel the present said church and encumber the said property…at said meeting at 59 Max Street…the 8th day of September 1925… for the sum of $7,000 …”

[65] Ibid.

[66] Asheville Citizen Times, June 12, 1928, page 2.

[67] See: Asheville City Directory, 1930.

[68] Asheville Citizen-Times, April 6, 1978, page 9.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Ibid.

[71] “Uprooted: Urban renewal in Asheville”, Mountain Xpress, Posted on March 8, 2020 by Thomas Calder. https://mountainx.com/news/uprooted-urban-renewal-in-asheville/

[72] 04/07/1987 HOUSING AUTHORITY CITY OF ASHEVILLE- PLAT EAST END VALLEY ST COMMUNITY IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM PARCELS 112-117, Db. 53/167.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[73] 05/13/1993 Connie B. Garrett to Cappadocia Fire-Baptized Holiness Church [NON/W/ DEED ] DB 870/639 BUNCOMBE CO Db. 1744/675.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[74] See:- https://www.eastendvalleystreet.org/ 0-y/