By Dale Wayne Slusser

“What are our Real Estate owners thinking of in not building houses?”[3], implored an anonymous subscriber to the Asheville News in November of 1869. In his (or her?) long appeal, the anonymous subscriber gave a comprehensive state of building, or lack of building, in Asheville, as well as an appeal for builders and tradesman: “We are aware that building materials are dear- lumber $1.75 per 100 feet, bricks, $10 per 1000. If men would show a disposition to build, and encourage the establishment of one or two good saw mills in our neighborhood and invite a few brickmakers to come here, these high prices would tumble down fast.”[4] Whether in direct reply to this appeal, or just by coincidence (or possibly by Divine providence) just a few months later in 1870, a young bachelor Englishman named James Buttrick arrived in Asheville. James had the skills, experience and ambition needed to ignite the building industry in post-Civil War Asheville.

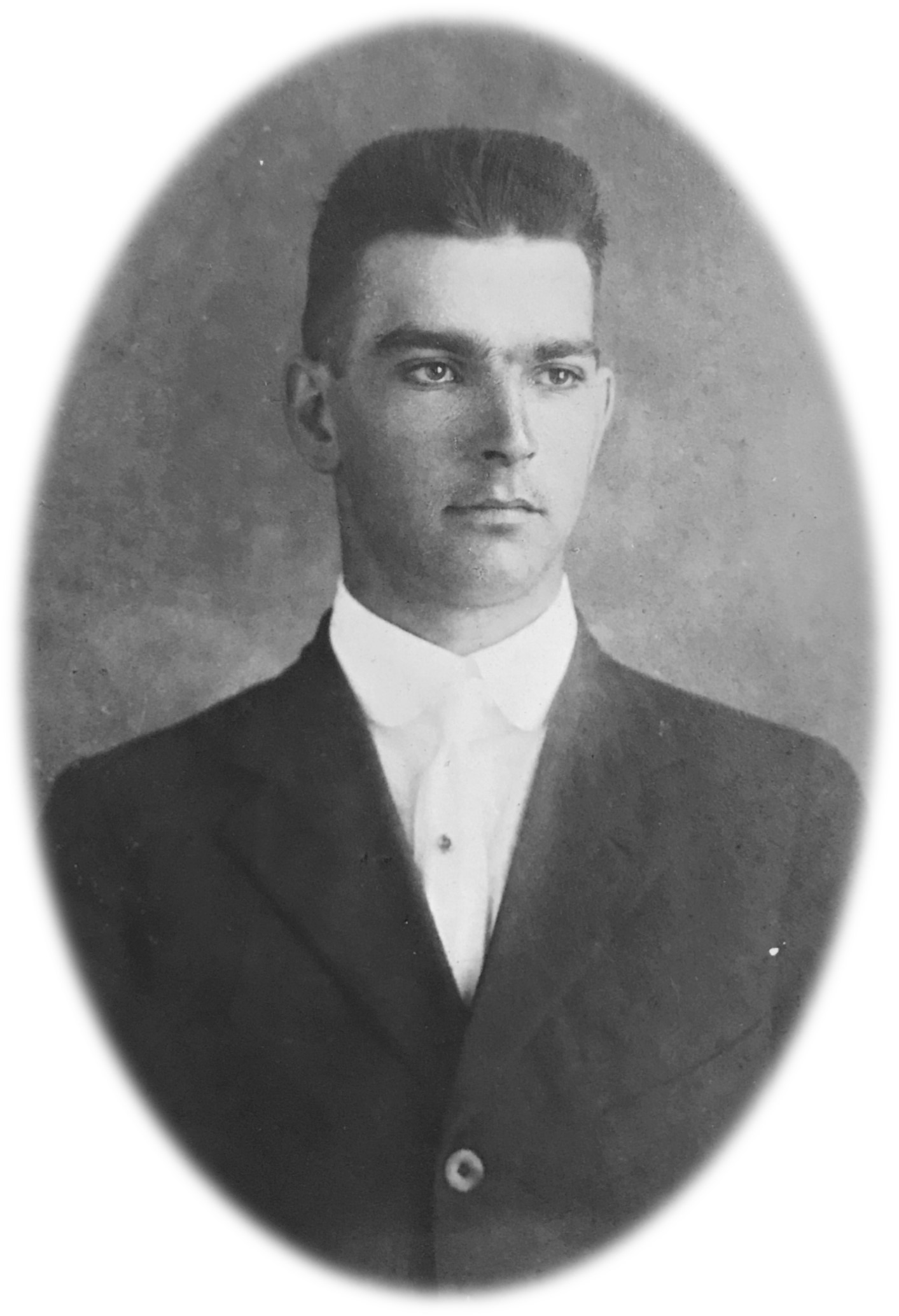

James Buttrick was born in Epworth, Lincolnshire, England on January 26, 1835 to William and Sarah Buttrick. James’ father, William Buttrick was a “Maltster” and Brickmaker in Epworth. A “maltster” prepared the malt from grain, usually to a brewer’s specifications. It was often a different occupation to that of a brewer who turned the malt into beer. As malting required air temperatures of 50°F-60°F, it could only be done between the months of October through May, and so many maltsters had alternate professions like brick-making, which was best performed during the summer months.[5] Although James Buttrick inherited his father’s business acumen, and later would exhibit the benefits from his experience of having been raised by a brick-maker, as a young man Buttrick chose to pursue the profession (or trade, as it was then called) of carpentry. In fact, in 1851, at the age of 16, he was apprenticed to wheelwright George Sampson near the village of Eastoft/Belton, just 2 miles north of Epworth.[6]

In 1871, shortly after his arrival, James Buttrick purchased 100 acres of land[7] on the west side of the French Broad River, just north of the Clayton and Jarrett lands in what is now Emma/Hazel Mill area of West Asheville. Buttrick would eventually establish a farm and homestead on the land.

In that same year, James Buttrick, a devoted Methodist, began attending services at the Miller Meeting House in West Asheville. The Miller Meeting House was small non-denominational house used primarily by Methodist preachers. But in 1871, through the efforts and encouragement of James Buttrick, the holders of the deed, executed in 1847, decided to properly deed the property to the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. “On February 17, 1871, Mr. Buttrick’s efforts were rewarded by the execution of a deed transferring the property to The Methodist Episcopal Church, South. “It was done,” the deed stated, “for and in consideration for the love we had for The Methodist Episcopal Church. South.” The deed was signed by Peter and Elizabeth Miller, Canada Cowan, Mary C. Cowan, George Miller, C. B. Miller, L.F. Miller, N.J. Miller, Anna Miller, J.B. Gaston and Parley Gaston. After this, the name was changed from the Miller Meeting House to Balm Grove Methodist Episcopal Church, South because of the balm trees growing on the lot.”[8]

Not long after the new deed was made, Dr. S.S. Grant resigned as Sunday School Superintendent, and James Buttrick took his place. “As the attendance at Sunday School and worship grew, the small building would not accommodate the people,”[9] so architect & builder, James Buttrick designed and built a second story on to the wood-framed meeting house. “The extra space was used for groups begun by Mr. Buttrick: The Sons of Temperance; the Juvenile Missionary Society (the first in the Holston Conference) called “Epworth Plants” in honor of John Wesley’s birthplace (the Epworth Plants later affiliated with a conference group called “Light bearers”); and a temperance society called “Band of Hope” for children and youth. The major group using the second story was The Sons of Temperance, an order for adults and youth promoting the cause of temperance locally and nationally. Mr. Buttrick, “a student of Methodist history and doctrine”, started the first Sunday School library with George Miller as the first librarian. A rare eight volume set of John Wesley’s works, now in possession of Trinity, bear the date 1887, and the signature of James Buttrick.[10] Buttrick’s devotion and ardent Methodism was no doubt as result of having grown up in Epworth England the birthplace of Methodism. As recalled by a grandniece of James Buttrick, “That was the home of Charles and John Wesley. John Wesley was the father of the Methodist Church. He used to preach in my great-grandmother’s kitchen [that was James Buttrick’s mother].”[11] Buttrick’s grand-niece also related that her grandmother, Theresa Buttrick Hackney (James’ sister) was “baptized from the same font the Wesley’s were”.[12] We can assume that was true for James as well.

Not surprisingly, during those first few years after Buttrick moved to Asheville, he met and courted Miss Martha Ann Cowan, daughter of Asheville jeweler and watchmaker, and fellow devoted Methodist, Canada Cowan. The couple were wed on May 22, 1873 in Asheville by Rev. John Boring.[13]

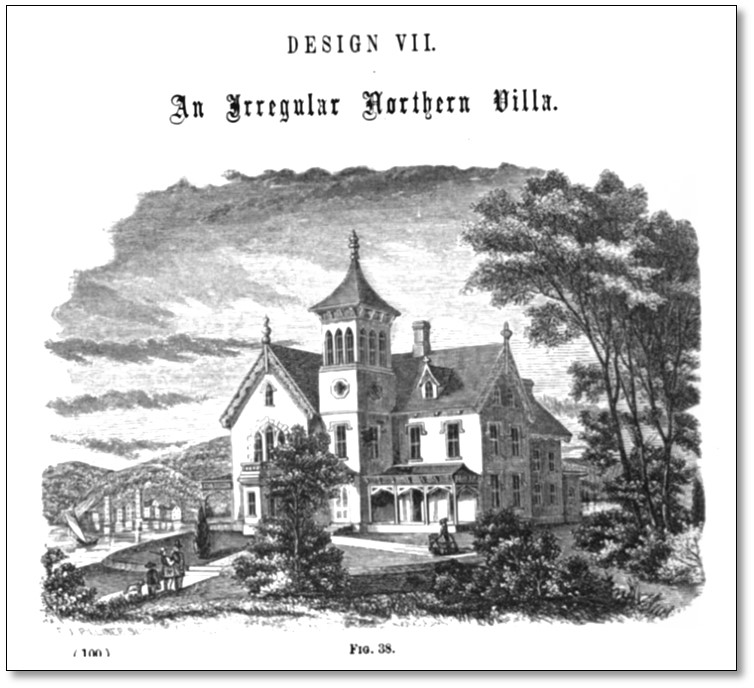

I believe that it was sometime shortly after his marriage, that James Buttrick began construction of his house on his Emma property. The majestic home, which he affectionately named “Epworth House”, was built on a prominence overlooking the French Broad River to the east, no doubt with a great view of Asheville to the southeast. Although we only have a fuzzy photo of the house, we can see that Buttrick built his house in the then popular Eastlake/Stick Style.

Shortly after the nineteenth century passed its quarter-century mark, beginning in the 1830’s, architecture took a dramatic turn. Breaking from the Classical design which had dominated European, British and American architecture since the late-seventh-century, artists and architects began touting the ideals of naturalistic design, based on idealized landscapes and exotic locales. The Classical movement sought to evoke the classical buildings of ancient Rome and Greece, but in contrast, architects of the Romantic or Picturesque Movement, as it became known, sought to provide architectural forms that evoked the romanticized regional (mostly European or British) architecture of Medieval manors and country houses. Although this movement would manifest itself in numerous revival styles during Victorian times, such as Stick Style, Eastlake Style, Italianate, Queen Anne and Shingle Styles, all these styles had similar characteristics. First, they all featured highly ornamental asymmetrical designs, and second, all the styles used the same buzz words for house-types. Just as we now use words like, split-level, bi-level, ranch, duplex or townhouse to describe a house-type, the Romantic revival styles used words like: cottage, suburban or country house, and villa. These were further refined as either Italian, Gothic, Swiss-chalet, or Oriental.

This new movement, as with the Classical movement, was proliferated by published architectural treatises and pattern books of the time. The Stick Style, as it was subsequently named, began to be popularized beginning in the 1850’s. “Architect-publishers like Gervase Wheeler and Henry Cleveland flashed the Stick look far and wide in their books Rural Homes (1854) and Village and Farm Cottages (1856).”[i] However, Buttrick’s design for Epworth House seems to me to have been influenced by such later publications of the 1860’s and early 1870’s, as: Samuel Sloan’s Homestead Architecture (1861); Sereno Edwards Todd’s, Todd’s Country Homes And How To Save Money (1868); George E. Woodward’s, National Architect (1869); Holly’s Country Seats (1863) by Henry Hudson Holly; Hobbs’s Architecture: Containing Designs And Ground Plans for Villas, Cottages, And Other Edifices (1873) by Isaac H. Hobbs; and Detail, Cottage, and Constructive Architecture by A. J. Bicknell (1873).

It’s often difficult to know the exact inspiration for a design, but certainly Buttrick’s home, for its time was quite stylish and certainly modern. Buttrick’s large two-story asymmetrical L-shaped house with its front projecting bay and center three-story tower, would have been called a “Villa” during its day. One contemporary report claimed that “Mr. James Buttrick of Emma post office perhaps has the best private residence in the county, if not in Western North Carolina, outside of Asheville, Vanderbilt’s mansion excepted, of Course”.[ii]

The Stick Style was also influenced by the 1868 publication of English architect Charles L. Eastlake’s book, Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery, and Other Details. Although primarily a furniture and interior design manual, Eastlake’s ornamental and carved designs were adapted for brackets, handrails, finials, and exterior ornament on houses built in the 1870’s through the 1890’s. “Increasingly affordable building materials and woodworking allowed for creative new uses of wood cladding and framing beyond the basic box structure. Stick / Eastlake style homes feature decorative trusswork, exposed half-timber framing, and an intermingling of vertical and horizontal planes. Roofs are typically steeply pitched with simple gables. “Ultimately, Stick-style houses are about carpentry…[sic],”[iii] so it’s not surprising to see that carpenter and woodworker, James Buttrick, chose this highly ornamental style for the design of his house.

1873 was a definitive year for Buttrick, as not only did he marry, but in July he began advertising his services as an “Architect & Builder”.[17] Buttrick advertised that: “Parties intending to Build can have Plans and Specifications on the most reasonable terms.”[18] Those intending to build were asked to leave their name and address at the Post Office. Although he advertised himself as an “architect” and builder, Buttrick was not a formally trained architect. Rather, he was a trained carpenter, who was carrying on the typical practice of antebellum builders who functioned as both designer (architect) and contractor. “By taking responsibility for the design, the expenditure of money, the manufacture of goods, and the use of workman,” writes noted architectural historian Catherine Bishir, “the antebellum contractor assumed a role in the building process seldom rivaled before or since.”[19] Although Buttrick and other post-Civil War builders continued this all-inclusive practice into the 1870’s and early 1880’s, by the late nineteenth-century, specialization in the building trades would result in the separation of the trades into carpenter, contractor, architect, building materials manufacturer, and building materials supplier. Eventually Buttrick became involved in all five of those trades-but that’s getting ahead of our story.

In December of 1873, Buttrick purchased a 2-acre lot on “Old Haywood Road”, now the corner of Haywood Street and Patton Avenue opposite where Clingman Avenue enters Patton Avenue. He built a wood-frame “shop” which he used as his office and workshop. He would later develop a portion the property into residential lots, which would include Buttrick and Turner Streets. An 1898 sketch biography of James Buttrick, published in the local newspaper, reported that Buttrick “started his career in the woodworking business, his shop being a wooden building near the intersection of Haywood Street and Patton Avenue, the only other shop of the class then here being the Clayton shop.”[20] Understanding the building practices in North Carolina during the mid-nineteenth century helps us to understand the nature of Buttrick’s “woodworking business”. “The contractor often manufactured many of his materials in his own shop-following the precedent of the carpenter who made his own moldings, doors, and mantles or the brick mason who made as well as laid bricks,”[21] writes Catherine Bishir.

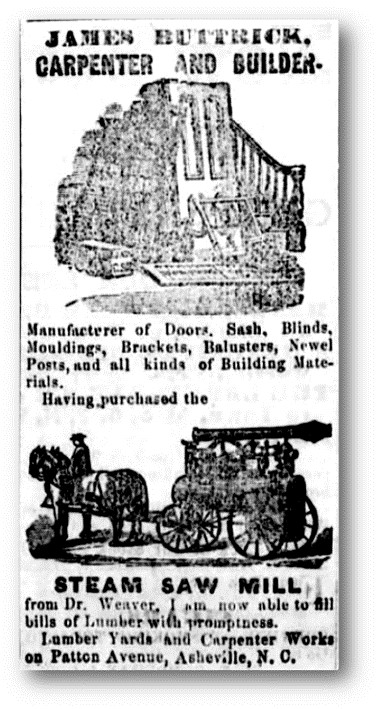

“Such builders, who had enough business to benefit from mass production of building parts, were among the first entrepreneurs to invest in steam-powered, large-scale manufacture of finished components as well as sawn lumber.”[22] These “shops” turned factory, became known as “Sash and Blind Works”. “Mr. Buttrick has built up, in his business of architect and builder”, announced an 1879 reporter, “one of the largest and most successful enterprises in Western North Carolina.”[23] We know from Buttrick’s numerous advertisements that, in his Sash and Blind Works, he manufactured the following: Doors, Sash, Blinds [shutters], Mouldings, Brackets, Balusters, Newel Posts, had-railing, matched flooring and ceiling boards, and dressed lumber.

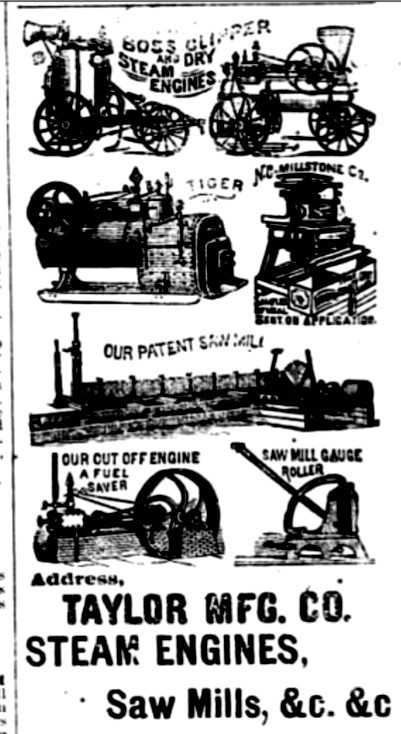

In the previously referenced newspaper report from 1879, it was further reported that Buttrick had “recently established at his works an extensive lumber yard, where he is prepared to furnish lumber in any amounts to persons desiring.”[24] This latter announcement was not surprising as previously, in 1878, Buttrick had in partnership with “Dr. Weaver” purchased a “portable steam saw mill” and established a lumbering business, no doubt to supply lumber for his Sash and Blind factory and his contracting business. “Messers. Buttrick & Weaver,” it was reported in 1878, “are doing a heavy business with their splendid saw mill. They move it around to suit custom. If the timber won’t go to them, they go to the timber. And Mr. Buttrick at his West-End Machine Works, is doing all a large force of good workmen can do working up this lumber.”[25] In 1879, Buttrick purchased Dr. Weaver’s interest in the “Steam Saw Mill”, and established their business as part of Buttrick’s “Lumber Yards and Carpenter Works on Patton Avenue”.[26] The “Steam Saw Mill” was a portable machine, which judging from the sketch in the advertisements, and from the fact that Buttrick was an agent (dealer) for the Taylor Manufacturing Company of Westminster Maryland[27], was probably a horse-drawn Dry Steam Portable engine, as shown in the vintage photo below. Using the same steam-driven technology developed and used to build steam locomotive engines, this “engine” was pulled from site to site by a team of horses-notice the wooden wagon wheels. A drive-belt was hooked over the side flywheel on the engine and then hooked up to an onsite or portable sawmill.

Although Buttrick’s sawmill was portable, a contemporary report, said that he operated “a sawmill in the country”.[28] In 1885, James Buttrick advertised the sale of his sawmill in conjunction with a Trustee sale of an Aultman-Taylor (successor to Taylor Mfg. Co.) 15 hp “Sampson” steam engine (owned by Wilson Boyd) which had been used to power Buttrick’s saw mill. From the description of the location of the sale, I believe that Buttrick’s “sawmill in the country” was located at Cathey’s Cove in the Hominy Valley, north of present-day Candler, NC. The photo below, which is a still-shot from a video of a live demonstration at the Fall 2013 Nittany Antique Machinery Association show in Centre Hall, Pennsylvania. It clearly shows how a nineteenth century “portable steam engine” was used to power a sawmill. Like the one Buttrick & Weaver used, the sawmills themselves could also, and often were, portable as well.

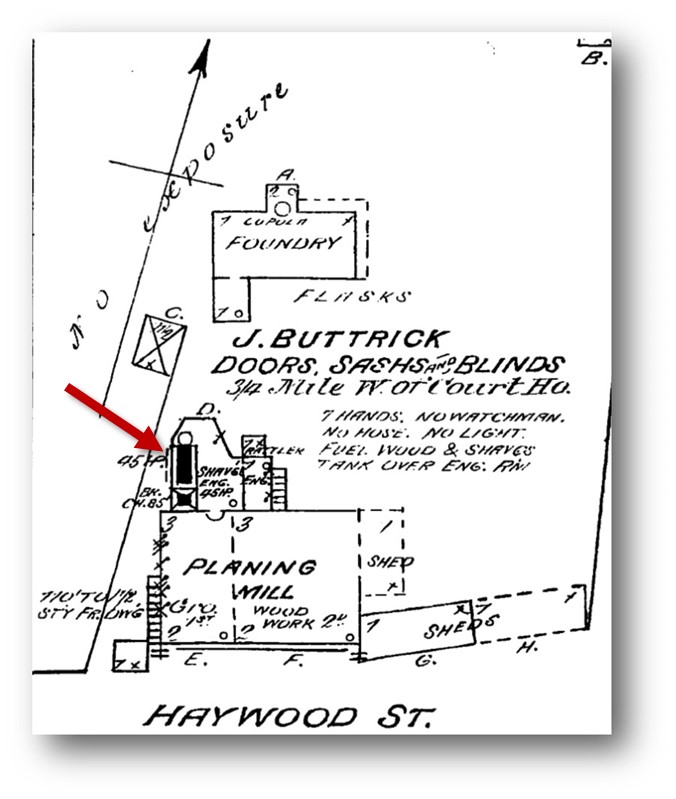

Buttrick also used a Taylor “Adjustable Cut-off Stationary Engine” at his Sash and Blind factory.[29] A look at the 1885 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, a close up of “J. Buttrick-Doors, Sashes and Blinds”, shows that Buttrick used a 45 horse-power engine to run the machinery in his factory. The engine was installed in a covered “engine room” behind the building and used the adjacent chimney for its exhaust.

By 1881, Buttrick, found that his wood-framed shop, due to his “go-aheadativeness”, as it was reported, “rendered his old quarters far too small.”[30] So Buttrick tore down his old shop and began construction of a new three-story brick building, 43 feet deep with a 70 feet long front facing Haywood Street. The basement story was exposed on the rear (northside) of the building, making the building appear to be only two-stories, as viewed from the street. A large brick chimney was built behind the building for the exhaust for his machinery and engines.

The 1885 Sanborn map shows that the new brick Buttrick building included a Grocery on the first floor, with the Planing Mill and woodworking shop on the second floor. The “sheds” shown on the right of the plan were probably used for lumber storage. The map also indicates that “7 hands” (employees) worked in the building.

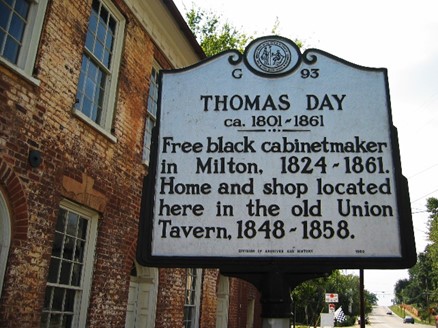

One of those that we know worked in Buttrick’s building, was an African American cabinetmaker Thomas Day, Jr. It appears that instead of being an employee, Day was mostly likely a tenant, operating his “cabinet shop” from the Buttrick shops. A contemporary account of Day’s Asheville shop described it as a place “where very beautiful work is turned out from our native woods.”[31]

Day was the son and namesake of antebellum cabinetmaker Thomas Day, Sr. Thomas Day, Sr. (1801-1861), an antebellum cabinetmaker and free man of color, was an artisan of extraordinary ability and character who produced a body of distinctive work unique in North Carolina. Although he was primarily a furniture maker, whose workshop was among the most prolific in the state, he is also credited with distinctive architectural woodwork for a North Carolina and Virginia clientele, including stairs, mantels, and door and window frames with forms akin to those in his furniture. Thomas Day, Sr. was born free in Virginia to John and Mourning Stewart Day, both free people of color. In 1825, Thomas Day and his brother John Day, Jr. moved to the trading town of Milton beside the Dan River in Caswell County, North Carolina. Day’s business grew over the next two decades, and in 1848 he purchased the former Union Tavern on Main Street as his dwelling and workshop and soon constructed an addition for his cabinetmaking operation. The national financial crisis of 1857 brought problems to Thomas Day. Like many other artisans, he could not collect on bills owed to him by customers and hence could not pay his own debts. In March 1858 his property was involved in an insolvency deed. Much of his property was sold. Through the help of friends, Day’s son, Thomas Day, Jr., who had joined him in his business, acquired ownership of the family home and workshop in 1858-59, and was able to keep the business going, even after the death of his father in 1861. Sometime after the Civil War (by 1880) Thomas Day, Jr. moved to Asheville with his family, including a daughter, son John W. Day, and his mother Aquilla. Day, along with his son John D. Day operated his shop in the Buttrick building until sometime around 1886-1888, at which time, he and his son John Day were hired by the newly opened Asheville Furniture Factory (which had opened in 1886). Thomas Day, Jr. left Asheville and moved west shortly after 1890, but his son John continued to live in Asheville until his death in 1918. John Day and other members of the Day family are buried at Riverside Cemetery in Asheville.

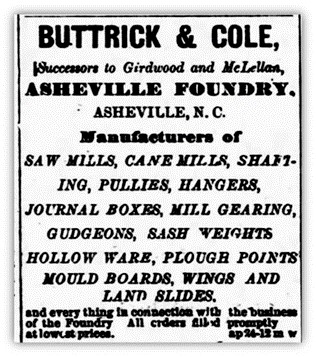

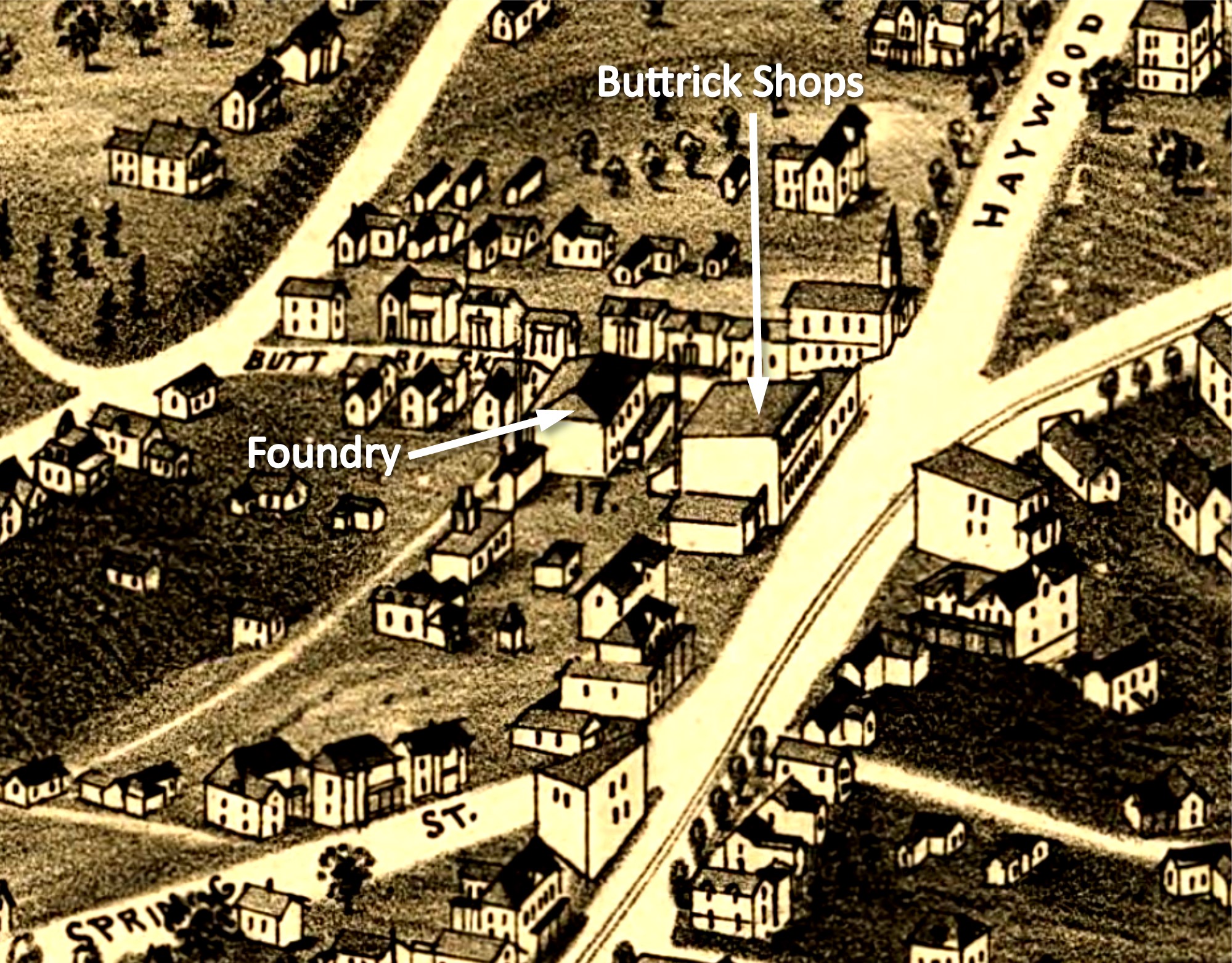

In conjunction with his Sash and Blind Factory and lumberyard, in 1884, Buttrick decided to build a foundry on his property, behind his shops (the foundry shows on the 1885 Sanborn Map). Buttrick partnered with John Burnett Cole to form the partnership of “Buttrick & Cole” to establish the “Asheville Foundry and Machine Shop”. Buttrick & Cole had bought out the Foundry business of Girdwood & McLellan, probably acquiring the necessary machinery and tools, as well as their clientele. It seems that Buttrick contributed capital, furnished the land and built the facilities, but that J. B. Cole operated and managed the establishment. A contemporary advertisement for the foundry gave the following list of products that it manufactured: “sawmills, Cane mills, shafting, pullies, hangers, journal boxes, mill gearing, gudgeons, sash weights, Hollo Ware, Plow Points, Mould Boards, Wings, and Land Slides, and every thing in connection with the business of the Foundry.”[32] In addition to the foundry’s production of “all kinds of machinery for Farm or Factory”, they also manufactured fireplace grates, andirons, and ovens.[33] The Foundry also operated a grist mill which was capable of producing 150 bushels per day.[34] Buttrick & Cole’s flour was sold under the brand name of “Champion City Mills”. [35]

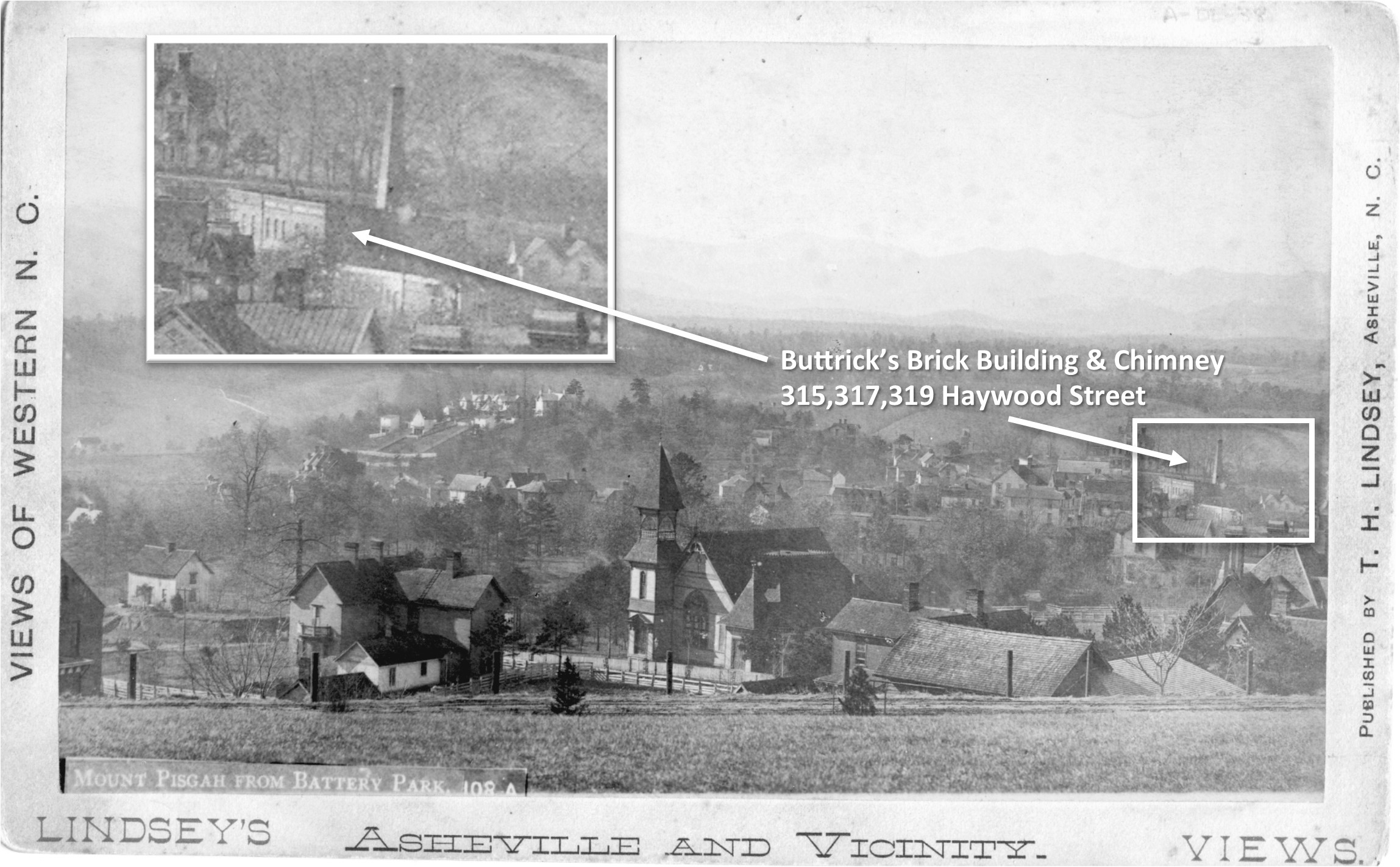

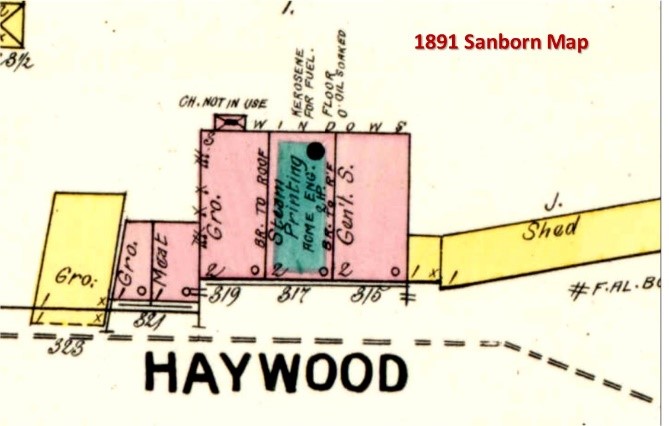

The Buttrick shops and Foundry show on the 1891 Asheville Bird’s-Eye View. The 1881 Brick building (numbered 315, 317, & 319 Haywood Street) sat right on the street just south of the intersection of Buttrick Street and Haywood Street. The Haywood Street Methodist Church on the adjacent corner of Buttrick Street is the only building that remains to this day. The entire “Buttrick Block” was demolished when Patton Avenue was extended in the 1950’s to connect to the newly built Smokey Park Bridge (Jeff Bowen Bridge). The Buttrick building also shows in an 1890’s T. H. Lindsey’s Stereoview photo of a view looking southwest from Battery Park hill. The brick building and huge chimney show in this photo; however, the foundry is out of view to the right (north).

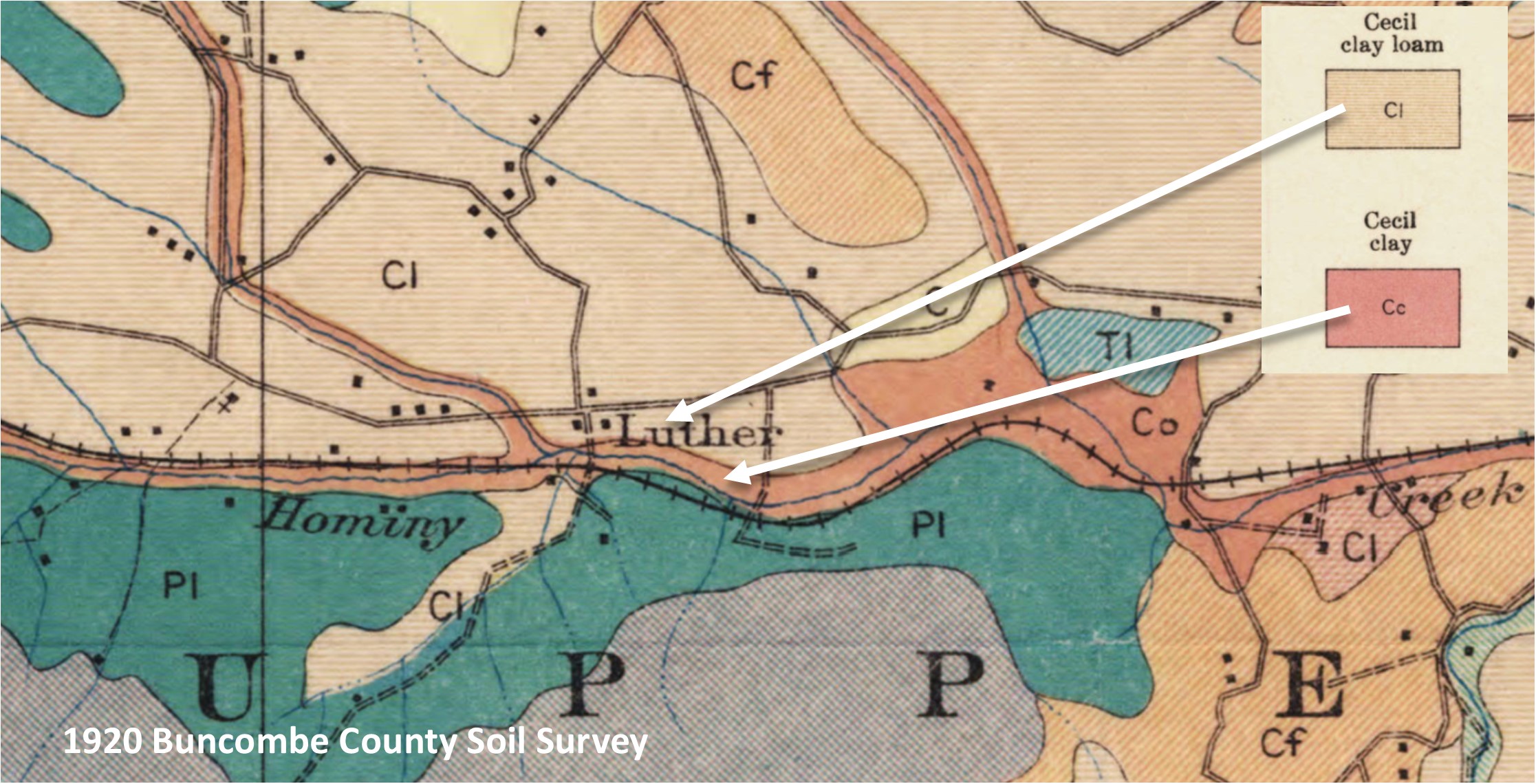

Contractor James Buttrick, following the all-inclusive approach to building, along with his woodworking shops, lumberyard, and foundry, also established his own “brickworks”. Shortly after building his shop, Buttrick established a brick plant on the western portion of his farm at Emma, NC, on the westside of the French Broad River. The location of Buttrick’s brickworks is obvious to us today as it was located on what is now appropriately named “Brickyard Road”, off Emma Road in modern-day West Asheville. A brickyard was a natural business for Buttrick who was raised by a “brickmaker and maltster”. Of course, being a Methodist and proponent of temperance kept him from dabbling in the malting business, as well! Buttrick operated the Emma brickyard until 1887, when he then sold the brickyard (property and business) to W. R. Penniman, who operated it under the name of “Asheville Brick Works”. An 1897 published report on the “Clay Deposits and Clay Industry in North Carolina” reported that the “Penniman Clay Bank near Emma”, has one of the largest deposits of sedimentary clays in the county.[36] A look at a 1920 Buncombe County Soil Survey shows that the brickyard property was located along a large deposit of “Cecil Clay loam”, a red-clay soil perfect for making bricks.

Although Buttrick was primarily in the building trades, he was also a consummate businessman, and so on occasion he ventured into other business opportunities that came along. In 1890 he “entered into the mercantile business”.[37] Around 1890, Buttrick closed his sash and blind factory, and erected dividing walls in his building dividing it into three stores, therein addressed separately as #315, #317, and #319 W. Haywood Street. Buttrick leased #’s 315 and 319 to tenants and reserved #317 for his own office, where he managed his various businesses, one of which by then was his real estate and development business. Although he was by trade a carpenter and builder, from analyzing his various property transfers during this time, it appears that his real estate development primarily (if not solely) consisted of buying large parcels of land and then dividing them into lots and then selling the lots (with no houses on them) at a profit. Besides developing lots on his own land along Buttrick Street (behind his shops), Buttrick had two other known developments one on “Depot Street” and one on “Charlotte Street”. The Depot Street development was a small parcel of lots along an alley off Depot Street, now known as Clingman Avenue. Actually, the development started at the lot at 73 Clingman Avenue at the intersection of Clingman Place and extended west along the northside of Clingman Place. None of the houses now on those lots date back to Buttrick’s time. The “Charlotte Street” development was on a parcel on the east side of Charlotte and bordered on the north by Raoul’s Albemarle Park, on the east by Albemarle Road, and on the south by Blair Street. I can find no houses in this development either that were built by Buttrick.

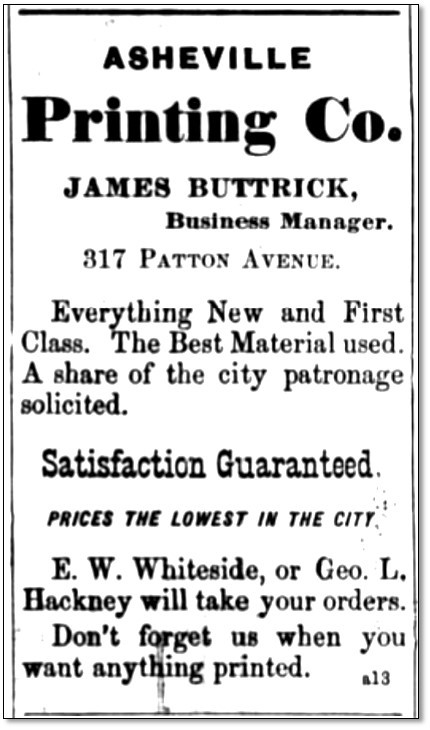

Another business that Buttrick entered into in 1890, was the printing business. I’m not sure that Buttrick intentionally set out to get into the printing business, but as a devout Methodist and Sunday School teacher, Buttrick always endeavored to find ways to spread the Gospel of Jesus (the “Good News” of salvation and the life-transforming work of Jesus Christ), and so when he was asked to help support the “The Asheville Methodist”, a newspaper started in 1887 by Rev. J. F. Austin of the Methodist Episcopal Church South,[38] Buttrick jumped at the opportunity, by buying “an interest” in the periodical and forming the partnership of Buttrick & Austin.[39] The “eight-page weekly” newspaper was described by a contemporary as “replete with high-toned, moral, Christian selections”.[40] When Buttrick first bought into the newspaper, it was being printed at “Court Place”-which from other references I believe to have been the offices of “The Democrat” another eight-page weekly newspaper, published and printed by R. M. Furman and David Vance at an office on North Court Place (we know as Pack Square). In January 1891, Buttrick established his own printing business, named “Asheville Printing Company” at his office at 317 Haywood Street and not surprisingly soon announced that the “Asheville Methodist was “being removed from Court Place to the Buttrick building, in the West End”.[41] Buttrick soon began advertising that because of their “New Type, New Presses,” and “Skilled Workman” he could provide job printing and-commercial printing services.[42] Three of the skilled workman that Buttrick hired were E. W. Whiteside, S. H. Bean, and George L. Hackney, the latter being his nephew.[43] George L. Hackney, was the son of James Buttrick’s sister, Theresa Buttrick Hackney and her husband William N. Hackney. In 1889, W. N. Hackney decided to emigrate with his family to Asheville. The Hackneys first lived with the Buttricks at Epworth House in Emma, but soon after their emigration that built their own house on the corner of Louisiana Avenue and Haywood Road (now the site of an Ingles grocery store). George was 21 years of age and single when he moved to Asheville with his family. His first job was as a bookkeeper for J. B. Cole Foundry, but then in 1891 his uncle hired him to manage the printing operations at Asheville Printing. George was so proficient at managing the operations that in 1892 Buttrick sold his interest in the Western North Carolina Methodist to P. L. Groome, and shortly thereafter sold the printing business to his nephew George. In 1904, George Hackney partnered with Dr. P. R. Moale to form Hackney & Moale, to continue as a job printing company. Later Hackney was also instrumental in forming a company that bought the Asheville News, which combined with the Gazette to become the Gazette-News, which eventually became the Asheville Times.[44]

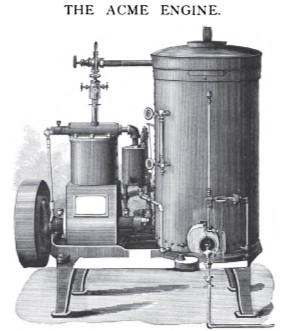

The 1891 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map shows the labels “Steam Printing” and “Acme Eng.” over the plan at #317, the office of Asheville Printing. This indicates that Buttrick was using one of his steam engines to operate his “Steam printing press”. I believe the “Acme Engine” was the so named engine manufactured by Rochester Machine Tool Works Ltd. A catalog description describes the engine as a “an upright, double-acting engine, with cranks 180° to each other. The fuel used is kerosene oil of 110° to 115° fire test, atomized by a steam jet.”[45] Supporting my suspicion, the Sanborn map also has a note behind the building which says, “Kerosene used for fuel”. But what was a Steam-Printing press? In the 1830’s William Koenig invented a revolutionary steam powered printing press. “Its design was fundamentally influenced by two ideas. The first was the use of steam power to run the machine. The second was the introduction of rotary metal cylinders, which allowed each page to be printed on both sides at the same time.”[46] The rotary steam printing press was the forerunner to the offset printer, used by printers for two centuries until the invention of modern digital printers.

As the nineteenth century was coming to a close, with Buttrick now passing 50 years of age, and having transferred his various businesses on to others, he decided to return to the trade of his youth-brickmaking. In 1893, Buttrick in partnership with W. A. Reynolds, established a new brick works at “Luther”, a small community west of present-day Candler, NC. He built his brick plant along Hominy Creek next to the Luther railroad station. Today we recognize the location as the property at the southeast corner of the intersection of Morgan Cove Road (SR 1205) and Old US 19-23 (SR 1130). A 1903 map shows that Buttrick also operated a “store” (probably a general merchandise store) at the corner. In fact, the store is still existing, though now vacant. I would assume that a brick from the store’s brick basement walls would be a Buttrick-manufactured brick? Luther seemed like an unlikely place for a brickyard, being seemingly remote from Asheville. However, a look at a 1920 Buncombe County Soil Survey shows that Buttrick had chosen a site located along a large area of “Cecil Clay” and “Cecil Clay loam”, similar yet larger in area then the deposits at his former Emma brickyard. The clay deposits were so large that the surrounding area was known as a center for the production of hand-made earthenware pottery. Just 2 miles northeast of Buttrick’s plant was the site of the Penland-Stone family Pottery shops, which had been in production since 1844. In fact, “the site was one of three places in North Carolina that was called “Jugtown” for its prolific output of utilitarian ware”.[47] The road from the site is still named “Jugtown Road”.

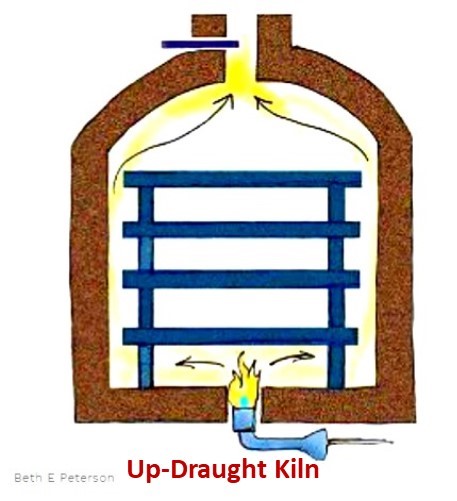

Buttrick’s located his brick plant next to the R. R. Station for ease of shipping. Although we don’t know how many kilns Buttrick had at his plant, we know that his kilns were “up-draught” arched kilns, “36 feet long, 16 feet wide, and 14 feet high”,[48] equipped with a furnace at each end. An up-draught kiln is one in which heated air is introduced into the bottom of the kiln, at or below the floor level, and then after the heated air circulates up and over the stacked raw bricks in the firebox, it is then exhausted at the top of the kiln through a dampered flue. The damper helps to maintain and regulate the heat/environment in the kiln. Although up-draught kilns (sometimes known as scotch-kilns) were not as efficient as down-draft, cross-draft, or Hoffman-kilns they were most prevalent in England, and thus more familiar to Buttrick.

In addition to producing brick, Buttrick’s plant at Luther also produced terracotta drain tiles. Although they were called “tiles”, they were really pipes, which were used by farmers and landscapists for drainage systems. “If you want to make from 25 to 50 percent more on your creek and river bottoms,” advertised Buttrick, “drain them with tiles.” The popularity of his drain tiles gained a boost in 1897 when an article titled “Biltmore Estate Farms”, reported that work was underway to make the estate’s bottom land (probably the farmland along the Swannanoa River where the estate had established a “Market Garden/Truck Farm) more productive by installing a new drainage system, using drain tiles. Although a small portion of the tiles were hauled in from the now-defunct Biltmore Brick & Tile Works at Biltmore Village, it was announced that “ a contract for a further large supply was closed with James Buttrick, whose yards at Luther’s siding on the Murphy Branch of the Southern railway, 12 miles from Asheville, are manufacturing an output of fine quality and at prices within the reach of practical agriculturalists.” [49] What a recommendation that was! We know from the Biltmore Estate records that Buttrick’s tiles came in multiple diameters-2-inch, 3-inch, 4 inch and 6 inches.[50]

Biltmore Estate not only continued to order drain tiles from Buttrick in the ensuing years, but also ordered and used large quantities of his brick as well, on the estate’s numerous landscaping projects. One project that we know that Buttrick brick was used for was on the construction of the estate’s water reservoir on Lone Pine Mountain. Built in 1899 as the principal water supply for the Estate, the 100 feet by 200 feet rectangular brick well with exposed 18-inch-thick exposed brick walls, stepped down the grade as necessary. The reservoir walls were capped tile, laid at a 45 degree angle to drain into the reservoir.[51] Although no longer used as the principal water supply for the estate, the reservoir is still used for water supply for landscape, irrigation and agricultural uses on the estate.

Another building project that we know used Buttrick brick, was on the construction Mitchell Hall at Asheville School, a prep-school still operating outside of Asheville. In 1903, contactor W. H. Westall reported that he was having trouble securing enough brick for the new building then under construction, but that he was able to secure “one hundred thousand brick” from the Buttrick brickyard.[52]

The Buttrick family operated the brickyard at Luther for several years, even following James Buttrick’s death, until selling it in 1913 to George Pinkney “Pink” Jones. Jones who was a farmer who had earlier purchased the nearby S. J. Luther farm, purchased the Buttrick property “including all buildings and machinery”[53], and operated the brick plant for a “many years”.[54] Today the site is a horse farm.

“James Buttrick is quite unwell at his home in West Asheville but is better than he has been,”[55] reported the Asheville Citizen-Times on September 4, 1903. But less than three weeks later, on September 20th the newspaper printed the alarming report: “Mr. James Buttrick was barely alive at eleven o’clock last night”.[56] Sadly Buttrick passed away the very day of the report. Buttrick was 68 years of age and was survived by his wife Martha and ten children, from age 29 to the youngest, James Arthur Buttrick, who was only 9 years of age. Funeral services were held at the Buttrick residence, Epworth House, the two days later.[57]

Although Buttrick’s shops, brickyards, and even his majestic residence (destroyed by fire in 1933) are long gone, his legacy lives on, mostly yet to be uncovered, in Asheville’s historic houses. Perhaps future historic house owners will uncover a Buttrick manufactured brick, window sash, mantel, fireplace grate, or door hinge in their historic home? But even they if don’t, we know that Buttrick was a prime contributor to Asheville’s nineteenth century-built environment which makes up a significant portion of Asheville’s historic buildings and neighborhoods.

Photo Credits:

James Buttrick as a Young Man- from James Arthur Buttrick, III (Great Grandson of James Buttrick) of Cutler Bay, FL.

Miller Meeting House-Asheville Citizen Times, December 18, 1932, page 16.- newspapers.com

Martha Cowan Buttrick- from James Arthur Buttrick, III (Great Grandson of James Buttrick) of Cutler Bay, FL.

Epworth House- from James Arthur Buttrick, III-copy originally from Carl Winkler, a recent owner of the Buttrick land in West Asheville, former site of Epworth House.

James Buttrick: Architect & Builder Advertisement– Asheville Weekly Citizen, July 24, 1873, page 4.- newspapers.com

James Buttrick: Carpenter & Builder Advertisement– Asheville Weekly Citizen, July 24, 1879, page 8.- newspapers.com

Taylor Steam Engine- photo from Jesse S. Byers, Littlestown, Pennsylvania 17340 -This photo is from the Collection of the Carroll County Historical Society, Westminster, Maryland. This engine is owned by Jesse Byers.- https://www.farmcollector.com/steam-traction/taylor-dry-portable-steam-engine

Steam Traction Engine- running a sawmill at the Fall 2013 Nittany Antique Machinery Association show at Centre Hall, PA 16828 . —https://www.youtube.com

Taylor Steam Engines Advertisement-a portion of advertisement, Asheville Weekly Citizen, October 23, 1884, page3., newspapers.com

Sawmill Location Map with Sale notices- a composite image by author, made from “Road Map of Buncombe County”, published by H. Taylor Rogers, Asheville, NC, 1903. -MAP 501, North Carolina Collection, Pack Library, Asheville, NC. Sale Notices from newspapers.com.

“J. Buttrick-Sashes and Blinds”-March 1885 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Sheet 1.- https://digitalsanbornmaps-proquest-com.

Thomas Day House/Marker– Milton, NC http://sites.rootsweb.com/~ncccha/images/historicalmarkers/thomasday.jpg

Buttrick & Cole Advertisement- Asheville Weekly Citizen, May 6, 1884, page 3.- newspapers.com

Buttrick Shops Bird’s-Eye View-1891 Bird’s-Eye View of Asheville (labels by author)- https://www.loc.gov/item/75694894/

Buttrick Building photo– Mount Pisgah from Battery Park. Published by T. H. Lindsey, Asheville & Vicinity, Class A, Views of Western N.C., #108A. -Image A240-8, North Carolina Collection, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

- R. Penniman Brick Advertisement- Asheville Citizen-Times, March 16, 1888, page 4.- newspapers.com

Buttrick Block Sanborn Map– Asheville, Buncombe Co., North Carolina, Nov. 1891, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Sheet 5.- https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/ncmaps/id/3912/rec/3

Asheville Printing Co. Advertisement-The Church Advocate, Asheville, NC, November 11, 1891, page 3. -newspapers.com

Acme Steam Engine-from: 1890 Article-Rochester Machine Tool Works Ltd., Acme Steam Engine- Source: “The Steam User 1890”, pg. 112. -http://vintagemachinery.org

Site of Buttrick Brickworks, Luther, NC Soil Map- composite by author from 1920 Buncombe County Soil Survey Map- https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/ncmaps/id/308

Up-Draught Kiln– “Different Types of Kiln Construction”, Written by Beth Peterson- https://www.thesprucecrafts.com/what-kind-of-kiln-is-it-2746127

Buttrick-Brick & Drain Tile Advertisement– The Lenoir Topic, Lenoir, North Carolina, July 6, 1897, page 2. – newspapers.com

James Buttrick-Brick & Drain Tile Letterhead-Letter from James Buttrick to Charles McNamee, dated May 24, 1899. Biltmore Estate Manuscript Collection, 1.1/1 B – Buttrick, James Box 16 Folder 444 Correspondence from James Buttrick, Manufacturer of Brick and Drain Tiles (Emma, NC), 1897-1902., Biltmore Estate Archives.

Lone Pine Reservoir – “Biltmore Treasure Talk, September 30, 2007”, photo by 2007 Eric Sauder -http://www.northatlanticrun.com/Biltmore2007_09.htm

Mitchell Hall Postcard– “Mitchell Hall”, Undivided Back postcard, c.1901-1907. Hackney & Moale Co., Publishers, The H. C. Leighton Co., Portland, ME. Manufacturers. Made in Germany. No. 3618.- http://www.angelfire.com/fl/thetrader/AS/index.html

James & Martha Buttrick and Children– from James Arthur Buttrick, III (Great Grandson of James Buttrick) of Cutler Bay, FL.

[1] “Build Houses.”, Asheville News, Asheville, NC-November 11, 1869, page2.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Build Houses.”, Asheville News, Asheville, NC-November 11, 1869, page2.

[4] Ibid.

[5] The British Malting Industry Since 1830, by Christine Clark. (London: The Hambledon Press, 1998), page 4.

[6] 1851 England Census, Eastoft, Lincolnshire, England accessed from Ancestry.com.

[7] Deed dated: January 4, 1871, James H. & Julia A. Merriman to James Buttrick-100 ACRES, Deed Book 34, page 74-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[8] From: An Extended History of Trinity, website of Trinity United Methodist Church, Asheville, NC.- http://trinitywavl.org/extended-history-trinity

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “A Generation’s End”, by Bob Terrill. Asheville Citizen-Times, October 30, 1971.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC, May 29, 1873, page 2.

[i] “Study of Stick Style Architecture and History”, by Gordon Bock (Updated: May 26, 2020; Original: Jun 30, 2010), https://www.oldhouseonline.com/house-tours/a-study-of-stick-style

[ii] Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC, January 23, 1900, page 2.

[iii] Old House Online-Ibid.

[17] Asheville Weekly Citizen, July 24, 1873, page 4.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Chapter 3-“Changes in Building Practice, 1830-1860”, from Architects and Builders In North Carolina: A History of the Practice of Building, by Catherine W. Bishir. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), page 148.

[20] “27 Years Superintendent: James Buttrick’s Record At Balm Grove- Sketch of the Man Who Has Been At the Head of the Sunday School, Since it Was Organized With Some School Facts” Asheville Weekly Citizen, January 28, 1898, page 4.

[21] Bishir, page 155.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Asheville Weekly Citizen, July 24, 1879, page 1.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Asheville Weekly Citizen, December 5, 1878, page 1.

[26] Asheville Weekly Citizen, July 24, 1879, page 8.

[27] Asheville Weekly Citizen, October 23, 1884, page 3.

[28] Asheville Weekly Citizen, January 28, 1898, page 4.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Asheville Weekly Citizen, December 1, 1881, page 1

[31] Asheville Weekly Citizen, April 19, 1882, page 1.

[32] Asheville Weekly Citizen, May 8, 1884, page 3.

[33] Semi-Weekly Asheville Citizen, October 24, 1885, page 1.

[34] Asheville Semi-Weekly Evening Journal, May 24, 1889, page 4.

[35] Asheville Citizen-Times, April 24, 1886, page 1.

[36] Clay Deposits and Clay Industry in North Carolina: A Preliminary Report, by Heinrich Ries (Raleigh, NC: G.V. Barnes, Public Printer, 1897), page 104.

[37] Asheville Weekly Citizen, January 28, 1898, page 4.

[38] Asheville Citizen-Times, April 24, 1886, page 1.

[39] Western North Carolina Methodist, June 25, 1891, page 3.

[40] Asheville Democrat, October 30, 1887, page 1.

[41] Asheville Citizen-Times, January 20, 1891, page 4.

[42] Western North Carolina Methodist, June 25, 1891, page 3.

[43] Western North Carolina Methodist, February 25, 1892, page 3.

[44] Asheville Citizen-Times, November 26, 1933, page 11.

[45] Info and drawing from- http://vintagemachinery.org/mfgindex/imagedetail.aspx?id=3333

[46] “Koenig and Bauer’s steam powered printing press”, on the Age of Revolution website: https://ageofrevolution.org/200-object/koenigs-steam-powered-printing-press/

[47] Craft Revival: Shaping Western North Carolina Past and Present-website: https://www.wcu.edu/library/DigitalCollections/CraftRevival/crafts/pottery-traditions/penland-stone-and-trull-potteries-candler.html

[48] “Inquiries About the Construction of Up-Draught Kilns”, from James Buttrick, Emma, NC., “Brick-Volume 10 No. 5”, May 1, 1899, (Chicago, Ill: Windsor and Kenfield Publishing Company), page 245.

[49] Asheville Citizen-Times, July 19, 1897, page 2.

[50] Referenced in December 2, 1897 letter from Charles McNamee to James Buttrick, on page 872 in the Superintendent’s Office Outgoing Correspondence Volume 21: 1897, Biltmore Estate Manuscript Collection, 1.1/2.-Biltmore Estate Archives.

[51] Info. from the “National Historic Landmark Nomination” for the Biltmore Estate, prepared by Davyd Foard Hood, September 2003.

[52] Asheville Weekly Citizen, April 10, 1903, page 3.

[53] James Buttrick Estate to G. P. Jones, 15 ACRES UPPER HOMINY TS, Deed book 183 page 182-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[54] “Candler Man to Mark 90th Birthday Today”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 6, 1951, page 50.

[55] Asheville Semi-Weekly Citizen, September 4, 1903, page 5.

[56] Asheville Daily Citizen, September 20, 1903, page 17.

[57] Asheville Daily Citizen, September 23, 1903, page 5. “The funeral services of the late James Buttrick were held yesterday morning, at eleven o’clock from the family residence, two miles west of Asheville.”