By Dale Wayne Slusser

The arrival of the railroad to Asheville in 1880, resulted in an exponential growth in its population, prompting a long-term building boom which began in the late 1880’s and lasted through the early 1900’s and up until its abrupt cessation at the “Big Crash” of 1929. The House at 1 Evergreen Lane, located just north of Asheville’s historic Grove Park neighborhood, was not only a product of Asheville’s continued building boom, but its origins is representative of the rapid development and re-development from the 1880’s through the 1920’s. The land on which the house at 1 Evergreen Lane was built, was part of no less than four separate development schemes, before starting its life as part of a fifth redevelopment scheme of 1916, named Holmwood Park, an off-shoot of the Proximity Park development.

In 1880, Asheville’s population was recorded as 2,616 residents,[1] but by 1890, it had swelled to over 10,000 residents.[2] As Asheville’s population began to explode in the 1880’s with the influx of wealthy health seekers, Asheville began to expand to the north, with the development of Asheville’s first “suburban” development, Montford, which was opened northwest of downtown in 1890. The city continued to expand in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, including to the northeast along Charlotte Street and Sunset Mountain. The Raoul family opened their Manor Inn on the east side of North Charlotte Street, on New Year’s Day, 1898, along with their adjacent Albemarle Park, with its large and small homes (cottages), which were mostly used for seasonal living. But then as the twentieth century dawned, came visionary Edwin Wiley Grove, who envisioned an upscale, high-class residential development which would attract the rich and famous from around the US. This “early twentieth century urban boom coincided with a national change in city growth patterns, as the streetcar and the automobile permitted and encouraged housing to move away from the dense urban city center into the ever more distant suburbs.”[3] However, Grove was not the first to look to North Charlotte Street for development. By the early 1900s, four men had bought large holdings on and at the foot of Sunset Mountain, including the lands along the end of North Charlotte Street. These four men were Walter B. Gwyn, George W. Pack, and Richard S. Howland, and Carl V. Reynolds, and their developments of the Sunset Mountain/North Charlotte Street area all pre-dated Grove’s development. Truth be told, Grove’s famous development was built on the foundations and very land of his four predecessors.

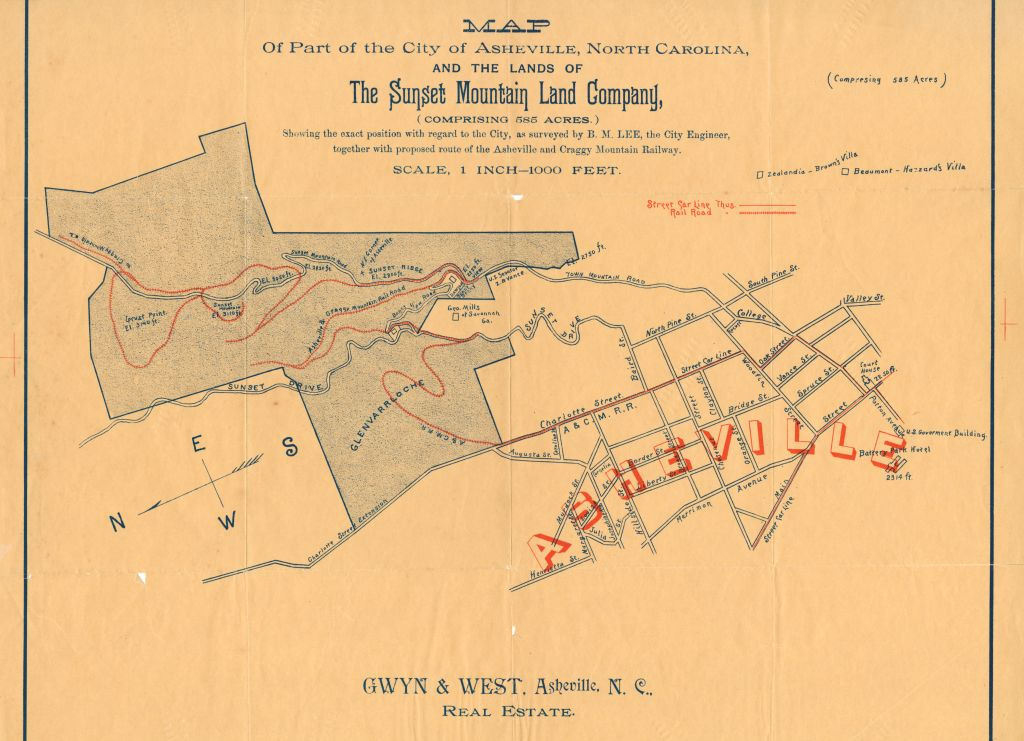

Let’s first look at the pre-development landscape of North Charlotte Street (which was then considered to be all the land beyond Baird Street) prior to 1890. From the early 1800’s through to the 1880’s all the land at the end of North Charlotte Street/Sunset Mountain area was one large farm, with a succession of just four owners. Noted Asheville historian, Foster A. Sondley, in a series of the early history of Asheville, first published in the Asheville Citizen Times, in 1898, speaking of early settler George Swain, wrote that Swain “was engaged for awhile in his old business of making hats, which he conducted at a place beyond the corporate limits of the city, on the eastern side of Charlotte Street, known for many years by reason of the business there carried on by him, and afterwards by his son-in-law the late William Coleman, as the Hatter-shop, and which was occupied for many years as a residence by the late Baccus [sp] J. Smith. Mr. Swain owned much land adjoining this place….”[4] Another description of this area was given to us in 1900 by early settler Albert T. Summey, who in describing what Asheville was like in 1842, recollected that “From the court house going east there was a road (not a street) which led by Mrs. Morrison’s home on the south side of the road to Wm. Coleman’s farm out on or near the end of Charlotte street car line.”[5] Records seem to indicate that William Coleman assumed the farm around 1830, following the 1829 death of his father-in-law, George Swain. Bacchus J. Smith, purchased the farm around 1845 and it remained in his possession almost until his death in 1886. The year before, in 1885, he had deeded the farm to his daughter Jennie Smith Gudger, the wife of Hezekiah A Gudger. “H. A. Gudger”, as he was usually addressed, was a lawyer, educator, diplomat, and jurist, who in 1885 was serving as a North Carolina State Senator. “Hon. H. A. Gudger,” announced the May 27, 1885 edition of the Asheville Citizen Times, “Having purchased the late home place of Bacchus Smith, just north east of the city, has had a handsome residence erected thereon, which he now occupies.”[6] It was further reported that, “Mr. G’s, good judgement and energy will soon convert the place into one of the most beautiful farms in the country.”[7] The Gudgers turned the old Bacchus Smith farm into a first-rate dairy farm, which they named “Glenverloch Jersey Dairy”, the “Glenverloch” name being an ode to the Gudger’s Scottish heritage,[8] and the “Jersey” signifying the breed of their cows! The Gudger’s farm, included a portion of the western slopes of what was then known as “Smith’s Mountain”, up to Sunset Drive (which was opened by Dr. Toomer Porter in 1886[9]). However, this idyllic rural property, of farm and mountain just beyond the city limits, which had survived since the early 1800’s, would soon be lost and gobbled up by enterprising developers. In 1887, just two years after building their new house, the Gudgers sold Glenverloch Jersey Farm, of 96 acres, to local real estate developer Walter B. Gwyn and his business partner George W. Swain, an out-of-towner and native of Danville, Virginia.[10] In February 1889, in an article aptly titled, “A Grand Scheme”, it was announced, without giving any names, that “it is proposed to apply to the present Legislature for a charter for a turnpike, also for a railway from Asheville to the top of Craggy.”[11] The reporter surmised that “The route to be adopted will probably be the same as the “Sunset Drive”, as far as its terminus to Pleasant Gap…”.[12] However, a few months later the actual particulars of the scheme were revealed. The Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway, was chartered on March 11, 1889 to build a 25-mile-long line to Craggy Mountain, northeast of Asheville, with the intent to eventually extend the line to Craggy Mountain to the east. However, it was not officially announced until August of 1890, in an article titled, “The Asheville and Craggy Mountain Dummy Road”, when it was then reported that Walter B. Gywn and his new business partner, William M. West, “have been negotiating some big trades in lands lying to the northeast of the city,”[13] not only for the new railway, but also for a development company, called “Sunset Land Co.”, to “improve” the lands over which the railway will travel. The article further reported that W. B. Gywn had bought out his co-owner, “Mr. G. W. Swain, of Danville, Va.” for $25,000 on the purchase of the 96 acre Gudger farm, for which the partners had purchased for $24,000.[14] The article further reported that the name of “Smith’s Mountain has been changed to Sunset Mountain”. Actually, a month earlier it was more correctly reported that W. B. Gwyn, William M. West, and H. L. Taylor “have incorporated the Sunset Mountain Land Company, to deal in real estate, to develop mineral land…”.[15] Ever the promoter, W. B. Gywn had a large scale map of the lands of the “Sunset Mountain Land Company” printed that showed the extent of its 585 acre property, as well as the route of the new railway. The map clearly showed the railway line leaving Charlotte Street and winding through the Gudger farm, mis-spelled as “Glenvarrloche”, on up to Sunset Drive and then on to the top of Sunset Mountain.

In 1887, just two years after building their new house, the Gudgers sold Glenverloch Jersey Farm, of 96 acres, to local real estate developer Walter B. Gwyn and his business partner George W. Swain, an out-of-towner and native of Danville, Virginia.[10] In February 1889, in an article aptly titled, “A Grand Scheme”, it was announced, without giving any names, that “it is proposed to apply to the present Legislature for a charter for a turnpike, also for a railway from Asheville to the top of Craggy.”[11] The reporter surmised that “The route to be adopted will probably be the same as the “Sunset Drive”, as far as its terminus to Pleasant Gap…”.[12] However, a few months later the actual particulars of the scheme were revealed. The Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway, was chartered on March 11, 1889 to build a 25-mile-long line to Craggy Mountain, northeast of Asheville, with the intent to eventually extend the line to Craggy Mountain to the east. However, it was not officially announced until August of 1890, in an article titled, “The Asheville and Craggy Mountain Dummy Road”, when it was then reported that Walter B. Gywn and his new business partner, William M. West, “have been negotiating some big trades in lands lying to the northeast of the city,”[13] not only for the new railway, but also for a development company, called “Sunset Land Co.”, to “improve” the lands over which the railway will travel. The article further reported that W. B. Gywn had bought out his co-owner, “Mr. G. W. Swain, of Danville, Va.” for $25,000 on the purchase of the 96 acre Gudger farm, for which the partners had purchased for $24,000.[14] The article further reported that the name of “Smith’s Mountain has been changed to Sunset Mountain”. Actually, a month earlier it was more correctly reported that W. B. Gwyn, William M. West, and H. L. Taylor “have incorporated the Sunset Mountain Land Company, to deal in real estate, to develop mineral land…”.[15] Ever the promoter, W. B. Gywn had a large scale map of the lands of the “Sunset Mountain Land Company” printed that showed the extent of its 585 acre property, as well as the route of the new railway. The map clearly showed the railway line leaving Charlotte Street and winding through the Gudger farm, mis-spelled as “Glenvarrloche”, on up to Sunset Drive and then on to the top of Sunset Mountain.

In the Fall of 1890, rough grading was completed on the Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway, from the northern end of Charlotte Street to the top of Sunset Mountain, a distance of only 2.5 miles. The line opened on May 1st, 1891. Passenger service was provided by a steam dummy engine and an open passenger coach. The dummy train ran from the end of the Asheville Street Railway at Chestnut and Charlotte streets to the end of the line on Sunset Mountain. Motive power was provided by an 0-4-2 dummy engine (Baldwin #9958) which had been built for the Knoxville Real Estate Co. in April 1889 and was their #2. It became Asheville & Craggy Mountain #11. The open coach appears to have been a 14-bench vis-a-vis (fixed back-to-back seats with half of the passengers riding backwards) open car built by Brill (order 1818) for Knoxville Real Estate in late 1887. [16]

At same time that he was developing the Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway and the Sunset Mountain Land Company, Gwyn had an even grander scheme in mind for the Sunset Mountain lands. In January of 1891, Gywn gave notice that he had made application to the “General Assembly of North Carolina” to incorporate the lands into a “town to be called Sunset Park.”[17] His application was accepted and on March 7, 1891, an act to “incorporate the Town of Sunset Park in the county of Buncombe” was officially ratified.[18] The first sale of lots, was advertised in September of 1891, however it was unconventionally advertised as 133-1/2 acres for sale “in Sunset Park” as “a whole $35,000 or $300-per acre in ten acre lots”.[19]

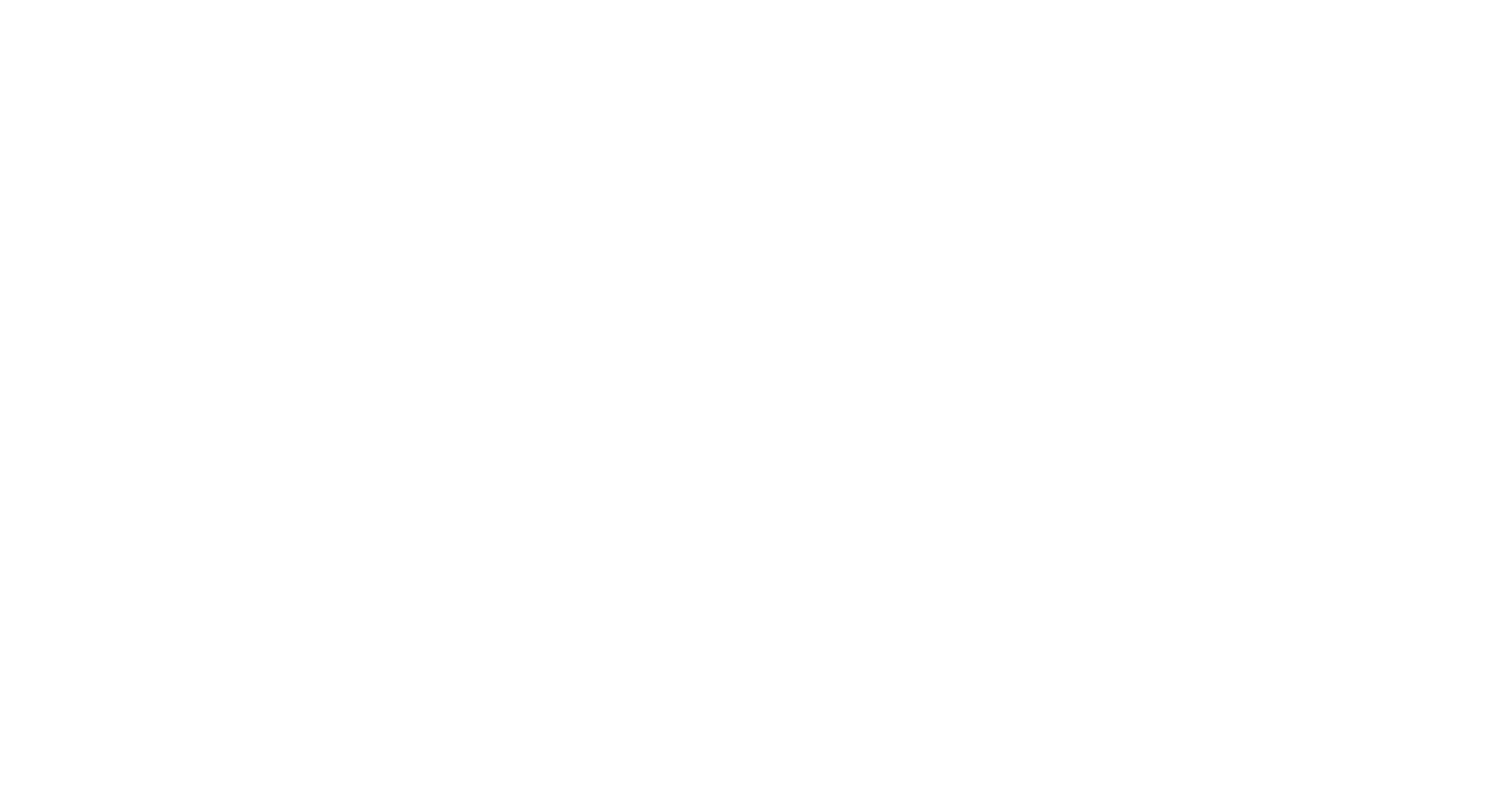

However, the development of the new town had to take back seat to the building of the railway. This is evident on the 1891 Bird’s-eye View of Asheville, which except for showing the Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway, shows a yet undeveloped North Charlotte Street, with only a few houses on its east side past Baird Street. These were no doubt, first Deake’s home and greenhouses, named Idlewild, and the second was probably Gudgers’ Glenverloch home. But by 1892, work was begun on developing the new town, and in April of 1892, Gywn had rented a “road scraper” from the City of Asheville[20] and began constructing the main thorough fare of the new town of Sunset Park, which was apply named “Grand Avenue”! Grand Avenue, which was to be “sixty feet wide” and is today’s Edgemont Road, was constructed just north of the railway line which ran up what is now Macon Avenue. Soon advertising jingles began to show in the newspapers-my favorite being, “Picnic parties on a lark, Take Dummy line to Sunset Park.”[21]

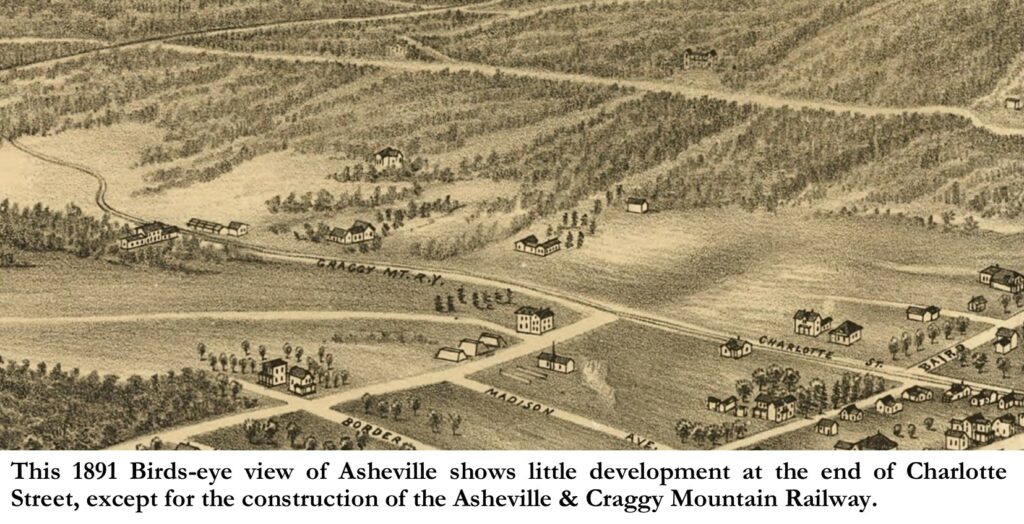

As the population of Asheville began to grow towards the northeast, a need for public transport arose which was not satisfied by the seasonal steam dummy service. To provide better service, the receiver of the Asheville Street Railway in the spring of 1893 leased the portion of the Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway track on Charlotte Street, north from Chestnut Street to the point where the line started the ascent of the mountain. A wooden station was built where the wire ended, and the steam and electric lines terminated there.[22] This terminus was on what is now Macon Avenue at the intersection of Howland Road. Eventually, a car shed and maintenance sheds would be built on the hill above the terminus to the southeast. Passengers, during the “season”, could take the streetcar to the terminus and then board the Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway for their excursion to the top of Sunset Mountain.

Aside from all the publicity and hype, the Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway was only a seasonal and therefore became a financial failure, and Gywn being a visionary without the capital to finance his dreams, had also overextended his finances trying to develop the Sunset Mountain Lands and the new Sunset Park town. In fact, only a handful of lots were sold, and those only being on the slopes of Sunset Mountain. By 1894, Gywn’s financial backers began to call in their loans, and as Grand Avenue lay uninhabited, looking like the road to nowhere, the Sunset Mountain Land Company and the Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway went into receivership. This meant that the new town of “Sunset Park” was also doomed, and in 1897 the North Carolina Assembly officially repealed the 1891 act of incorporation, and the town of “Sunset Park”, which really never was, became permanently no more! However, in 1895, the Sunset Mountain Land Company and the Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway were purchased by George W. Pack.

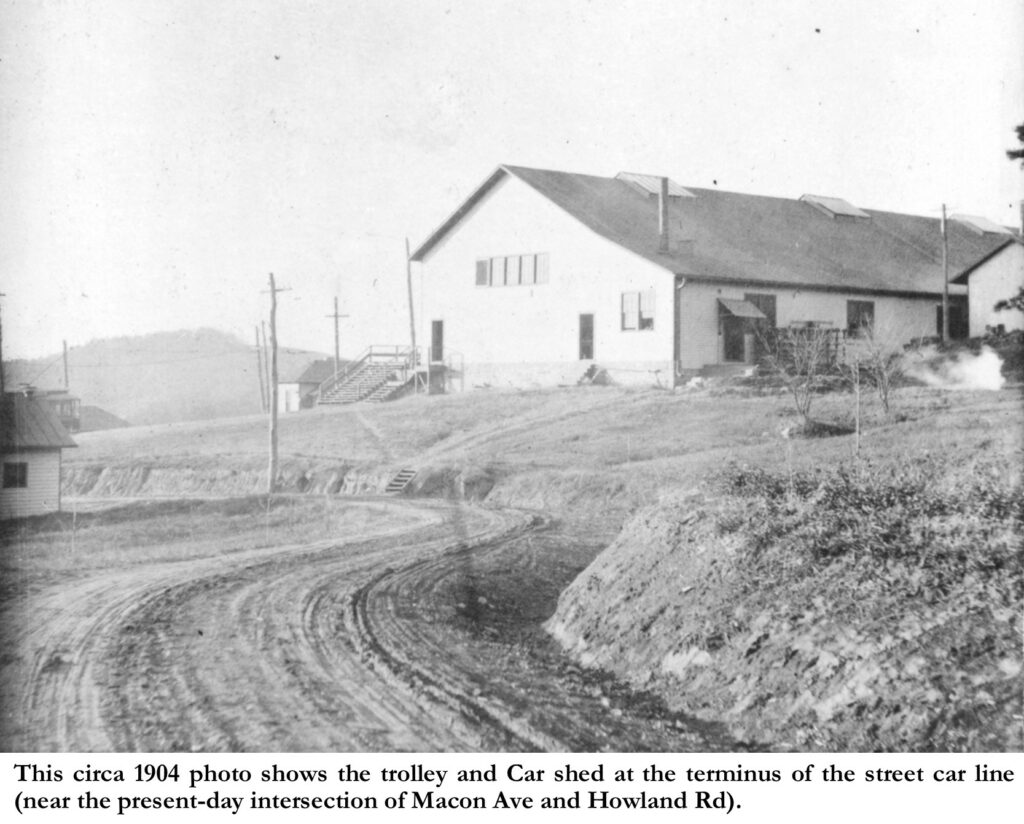

George Pack came to Asheville in 1885 from Cleveland, Ohio. He had made his money in the lumber industry and was drawn to the area because of the mild climate.[23] He invested, philanthropically in Asheville’s late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century development. His legacy still remains today on Pack Place, Pack Square, and Pack Memorial Library. Pack seemed uninterested in full scale development of the former Sunset Park into a residential development, and so besides leasing out Glenverloch, the former Gudger home, the land remained undeveloped, until 1898, when George W. Pack, in another act of philanthropy, offered to donate to the Swannanoa Country Club, “the use of the tract of land at the end of the Charlotte street car line, known as Sunset Park and embracing some 20 acres.”[24] Pack would donate the land to be used for the golf links for five years with the added provision that if he were to decide to use the land for other purposes after five years, that he would “fully compensate the club” for the money that had spent towards the property’s improvement.[25] The club, which was originally called the Swannanoa Hunt Club, was first housed in a clubhouse at the Battery Park Hotel in downtown Asheville. It quickly became a prominent social institution, and soon transitioned from hunting to golf and recreation. The golf links themselves were not at Battery Park, instead they were in West Asheville prior to 1899.

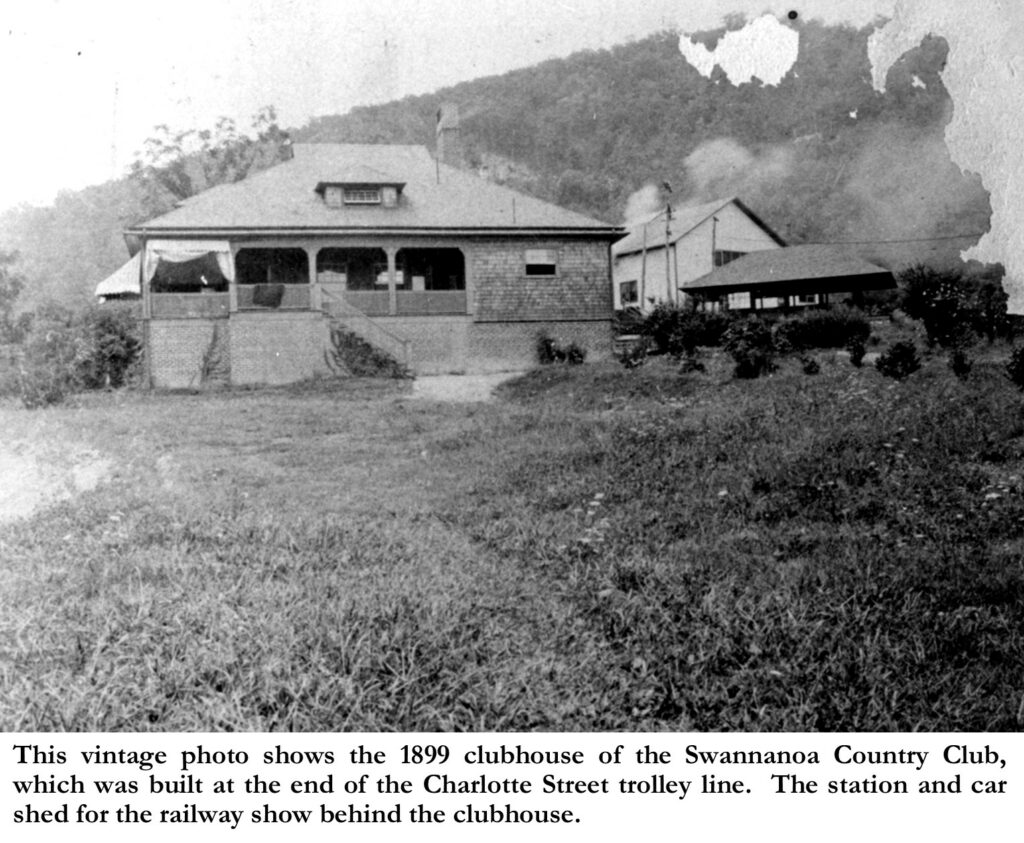

George Pack also donated the initial funds to kickstart the club’s fundraising to pay for the new golf course and clubhouse. It was proposed to build the “finest golf, cricket, and tennis field in the south”.[26] Architect Richard Sharpe Smith was hired to design a shingle-styled clubhouse. This new clubhouse, which opened in November of 1898 was described as “a story and a half enclosed in shingle finish and under a low-gabled roof from which appear numerous bay outlooks [aka dormers]. Broad verandas surround the house on the north, west, and south. On the southern exposure the entrance from carriages is merged in the veranda by an easy flight of steps through the balustrade at this point.”[27] The interior included a 24 foot square Assembly room, with a 15 foot-high ceiling, and “[28]a large open-hearth fireplace with “chimney seats beneath a springing arch of 14 foot spread.” The clubhouse also included a café and dressing/locker/shower rooms. A few surviving photos clearly show that the clubhouse was built at the eastern end of Grand Avenue (now Edgemont Road). The trolley line had already been extended down Charlotte Street, with a line running up to the terminus on Macon Avenue. The trolley line’s street car barn and pavilion station show behind and above the clubhouse in the photos.

Richard S. Howland, editor of the Providence Journal moved to Asheville in late 1899, where he first moved into a cottage in Albemarle Park, while he awaited completion of a house he was building on the side of mountain just below Sunset Drive. In the Spring of 1900, at about the time that Asheville Electric was making its move to control all of the city lines, Howland purchased the rights of way, charter and other property of the Asheville & Craggy Mountain Railway.[29] Then in June of 1900, Pack sold the Sunset Mountain Lands of two tracts, with a total of 330 acres, to Richard S. Howland of Providence, RI, for $14, 820.[30] The lands were excluding of the lands of Swannanoa Country Club property.

Despite the success of the Swannanoa Country Club, when Mr. Pack died in1906 his donation of and for the golf course did not continue to be honored by the family, and in February 1907, son Charles sold the 130 acres containing the golf links to a consortium of prominent citizens—Dr. C. V. Reynolds, D. C. Waddell, Jr., H. R. Millard, C. C. Millard and his wife Grace Millard—for $26,000.[31] The consortium then formed and incorporated the Proximity Park Company, in order to develop their newly purchased lands into a residential park. The five stockholders were Dr. C. V. Reynolds, D. C. Waddell, Jr. F. R. Hewitt, and brothers, C. C. Millard and H. R. Millard. Of course, this transaction would leave the Swannanoa Country club homeless. Initially, the newspaper reported that “unless their offer of it to the Golf Club is accepted, the purchasers will plat the land, layout streets and improve it, and then offer the lots for sale to those who will build handsome homes.”[32] But then the consortium decided to sell off 40 acres of the 130 acres property to the club for $15,000 to build a new clubhouse and golf links.[33] Concerned club members and citizens rallied together and not only re-organized the club as the Asheville Country Club, but they then accepted the consortium’s offer and gathered subscriber’s to fund the relocation. They moved their campus to the offered 40 acres, still on the former club property, but to the north at the end Charlotte Street just beyond the northern boundary of the Proximity Park development.

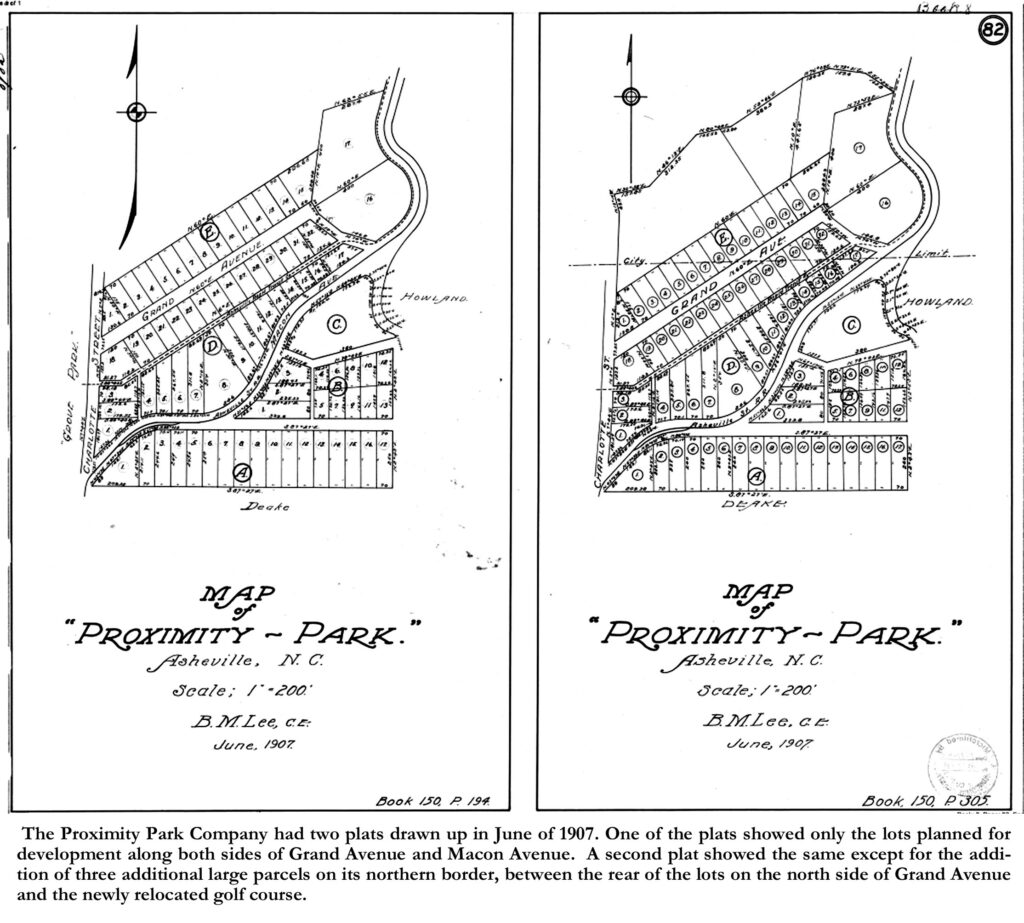

The Proximity Park Company had two plats drawn up in June of 1907. One of the plats showed only the lots planned for development along both sides of Grand Avenue and Macon Avenue. A second plat showed the same except for the addition of three additional large parcels on its northern border, between the rear of the lots on the north side of Grand Avenue and the new golf course. Both plats showed the right-of-way along Macon Avenue for the Asheville Rapid Transit Company’s street car line.[34]

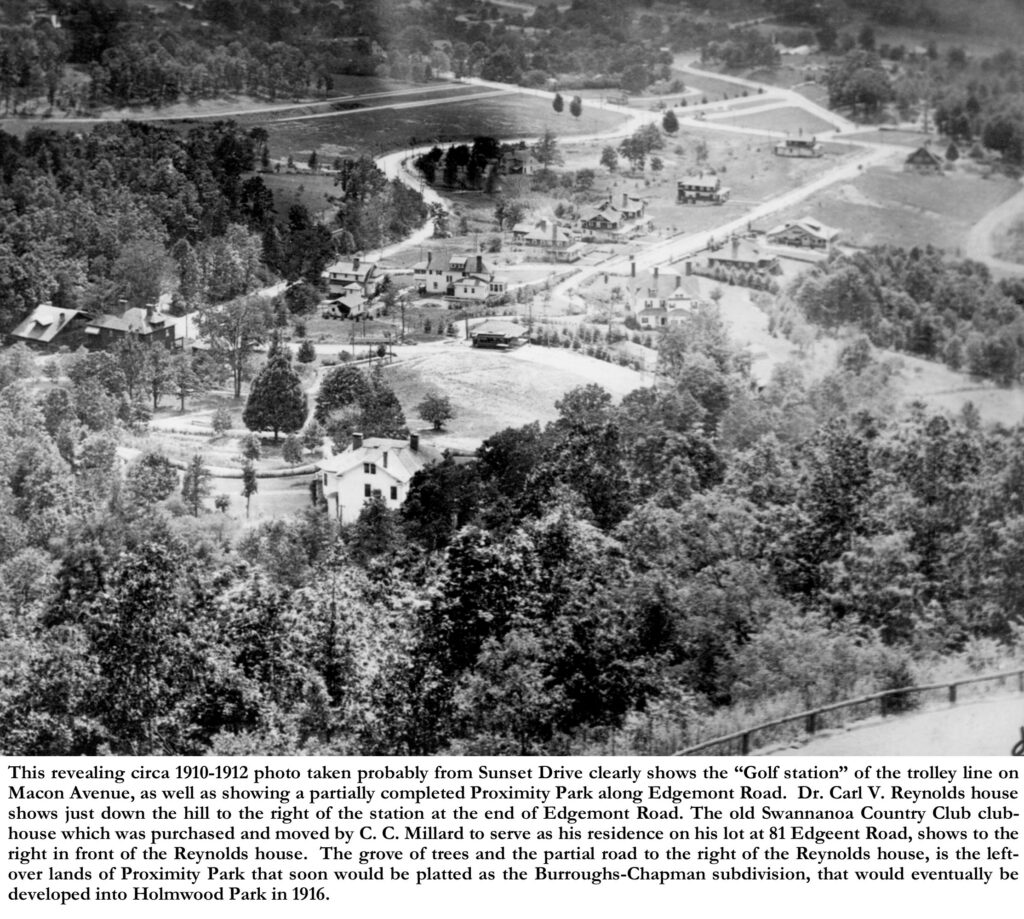

Dr. Reynolds soon commissioned an impressive Neoclassical Revival-style house for himself and his new wife, Edith, within the newly purchased lands at the end of Grand Avenue. He named his new home Edgemont, resulting also in the renaming of Grand Avenue to Edgemont Road. C. C. Millard, one of the incorporators ingeniously, had the former Swannanoa Country Club clubhouse moved 700 yards on to his newly purchased lot on the northside of Grand Avenue (now 81 Edgemont Road).

Proximity Park was slow to develop and by 1909, the corporation decided to sell the block of lots along both sides of Macon Avenue to Edwin W. Grove. Grove had already begun developing his new Grove Park residential park on the west side of Charlotte Street, opposite Proximity Park. Grove, at the same time also purchased numerous other tracts on Sunset Mountain above (east) and north of Proximity Park, setting up for the eventual building of the Grove Park Inn in 1913. The sale of the Proximity Park lots to Grove served as an omen for the Proximity Park Company’s soon to be announced dissolution. In May of 1910, the Proximity Park Company was officially dissolved.[35]

Despite the dissolution of the Proximity Park Company in 1910, the development would continue as most of the lots along Edgemont had already been sold and would soon be built on. Also, Dr. Carl V. Reynolds had purchased some of the unsold lots, including the large undivided plots that had shown on the 1907. A 1914 deed, made to clarify and confirm Dr. Reynold’s intent in a previous 1911 deed[36], tells us that Dr. Reynold’s had purchased these properties “with the intent and purpose of passing the legal title to said lands to the said Reynolds as Trustee for Annie R. Burroughs and Minnie R. Chapman.”[37] The 1914 deed further notes that because Burroughs and Chapman have paid in full the purchase money to the directors of the former Proximity Park, that they legally hold title to the lands. Annie R. Burroughs and Minnie R. Chapman were the sisters of Dr. Reynolds. Annie had been married to Dr. James R. Burroughs, who had passed away in 1910, and Minnie was married to S. F. Chapman, a local lumberman and businessman. In 1913, after the 1911 transfer, Burroughs and Chapman had their properties platted for development, but as large lots rather than the 25 foot to 50 foot wide lots typical in speculative developemnts. I suspect, as you’ll see later, that Minnie’s husband S. F. Chapman had an active role in selling and developing the “Burroughs-Chapman” land.

In the ensuing three years, Burroughs & Chapman sold a few lots, mostly along Charlotte Street. But then in 1916, it appears that S. F. Chapman had decided to use his wife and sister-in-laws’ lands for a new and innovative development project. The front-page headlines of the September 30, 1916 edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times, boldly announced: “DEVELOPMENT CALLING FOR $150,000 ON EDGEMONT ROAD NEAR GOLF LINKS BRINGS NEW CAPITAL TO ASHEVILLE- Syndicate of Asheville Capitalists, Including S. F. Chapman and Officials of Carolina Wood Products Company, Will Make Highest Class Development Here Since Date of E. W. Grove’s First Operation”.[38] The ensuing article explained that Chapman had recently added additional tracts to the tracts already owned by “Mr. Chapman and his associates in the neighborhood,”[39] which included the unsold Burroughs-Chapman lands. The project was lauded as “the last word in modern housings, and it is said, will incorporate many new ideas in homes new to Asheville.”[40] Although it stated that “no less than twelve” houses would be built, and that some would be for sale and some for rent, the article made no mention of the role of Carolina Wood Products Company, nor of the uniqueness of the new development.

So, who was “S. F. Chapman”? “S. F. Chapman” was Shepherd French Chapman, affectionately addressed as “Frank Chapman”, who was the son of Leicester Chapman, the namesake of Leicester, North Carolina. By 1916, Frank Chapman, who was an expert lumberman, had already had extensive experience in organizing and executing large-scale projects. Chapman had been the prime organizer and active partner in the Craggy Mountain Lumber Company and the Bee Tree Railroad in 1904, which were responsible for timbering the land of Craggy Mountain, the site of Asheville’s watershed. Chapman had also been the organizer of several other projects including, the Tallasee Power Company on the Tennesse River, the Yellow Pine Lumber Company in West Virginia, and the Tennesse & Carolina Railroad.[41]

Frank Chapman used his experience in organization to develop his “syndicate”, which constituted a collaboration of Chapman’s newly formed, “Holmwood Realty” and the Carolina Wood Products Company. Chapman formed the “Holmwood Realty Company” in August of 1916 with a capital stock of “$100,000 divided into 1000 common shares” with the proviso that they could commence business when they had 250 shares. Chapman satisfied this proviso by purchasing 248 shares at the start.[42]

Involving the Carolina Wood Products was the uniqueness of Chapman’s development. Carolina Wood Products acted as a modern-day design-build firm on Chapman’s development, being responsible for both the design and construction of Chapman’s houses. Carolina Wood Products Company was also a newly formed company, having just incorporated in January of 1916, “to manufacture ready-cut houses, furniture, flooring”.[43] Taking the popular “catalog house” concept, then being marketed by other companies such as Sears, Roebuck & Company and Montgomery Wards (Wardway Houses), Carolina Wood Products not only designed, and sold “ready-built” houses, but they also provided construction services to build them. Carolina Wood Products was a large corporation from the start, as in 1916, they not only were producing truckloads of furniture and furniture parts, but they also had a number of local building projects going on. In addition to the Chapman development, they were concurrently providing design and construction services for Jake Childs in the building of the new Kenilworth Inn and the building of several speculative bungalows next to the Inn.

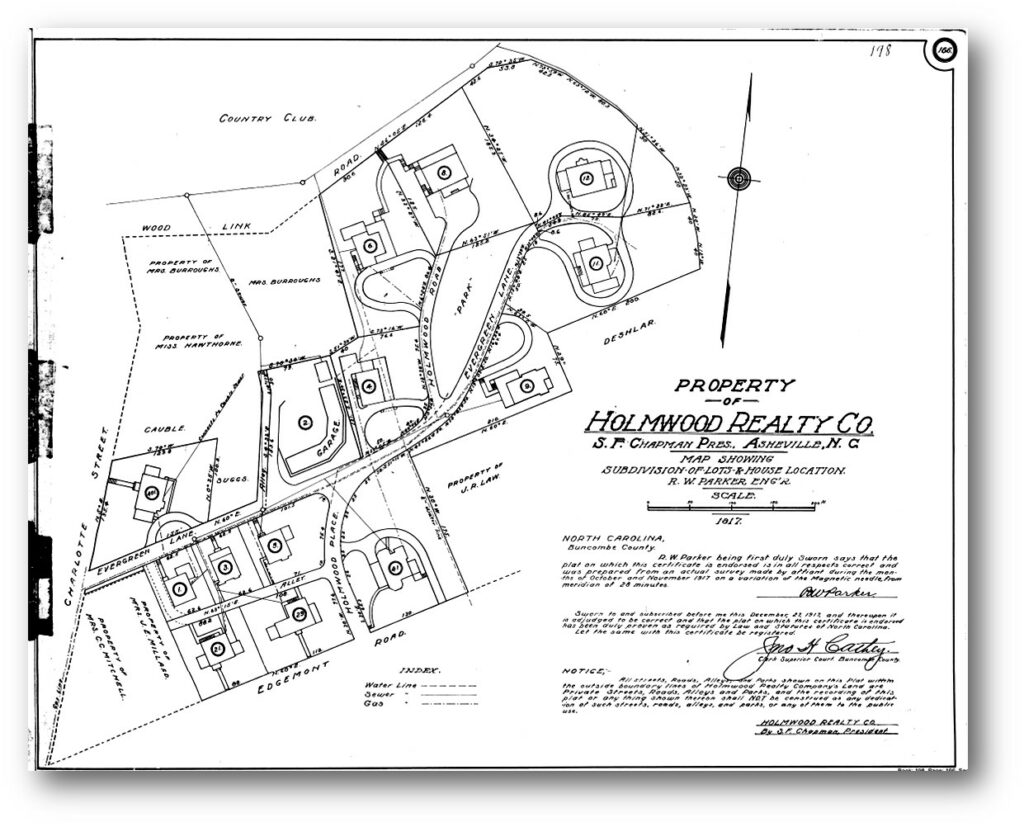

Chapman named his new development “Holmwood Park”. Although I’m not sure, I suspect that “Holmwood” came from Chapman’s British heritage, with his father having immigrated to Asheville from England. Interestingly, Frank’s sister Rose Chapman, earlier had an arts & crafts studio at her Rosscragon estate in Arden, NC which she named “Holmwood Studio”. Another unique aspect of Holmwood Park is that it was not platted until AFTER it was finished, and therefore included not just the lot subdivision but also the footprint of each house along with their accompanying walks and driveways. The heart of the development was a new street named Evergreen Lane off Charlotte Street, just north of Edgemont Road. A cross street, curved across the middle and connected to Edgemont Road. The houses mostly straddled Evergreen Lane and Holmwood Road, except for two houses which fronted on Edgemont Road.

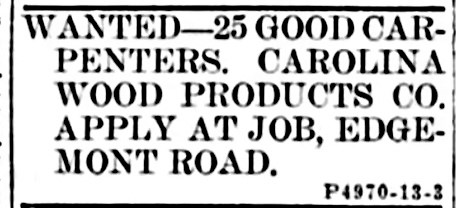

Chapman obtained the building permits for the houses beginning in March of 1916.[44] However, their design and construction were handled by Carolina Wood Products. E. A. Fonda, a registered architect from Florida, who had recently joined Carolina Wood Products as the general manager of their “House Department”, was responsible for the design of the houses and their layout on the site. Although the house at 1 Evergreen Lane was designed in a Dutch Colonial style, Fonda designed the thirteen houses in Holmwood Park to read like a ready-built house catalog, with various styles, Georgian, Colonial, Arts & Crafts Bungalow (both Craftsman & California Bungalow styles), and Shingle-style. In addition to the thirteen houses, a community garage (on Lot 2) was provided, and no doubt also designed by Fonda. Construction of the first houses began in the Spring of 1916, and the magnitude of the project was evident as in May of 1916, Carolina Wood Products began running ads for “25 Good Carpenters. Carolina Wood Products Co. apply at Job, Edgemont Road.”[45] Construction on the first few houses was finished by the Fall of 1917, as realtors began then to advertise their availability. The houses were first designed and built as furnished houses. The first advertisement that appeared for the houses, under “FURNISHED HOUSES” touted their uniqueness: “THOSE are very artistic houses which the Carolina Wood Products Company built for Mr. S. F. Chapman and his associates in Edgemont. They are practical as well and the appointments, furnishings and hangings will certainly satisfy the most fastidious.” [46] Interestingly, none of the first advertisements called the development Holmwood Park, nor used the word “Holmwood”, both only referred to them as “Chapman Houses”. An early advertisement, titled “Those Chapman Houses”, claimed that “You haven’t seen all of the best unless you’ve seen those Chapman houses.” The same article indicated that the rents varied from $120-$210 per month. Another advertisement from 1917 says, speaking of the Chapman houses, “Most all finished (the woodwork) ivory enamel, rugs, furniture and all interior decorations selected by an expert, the grounds laid out by an experience landscape gardener”.[47] I wonder if all or most of the furniture was produced by the Carolina Wood Products, as furniture was the bulk of their manufacturing? If so, has any of those pieces survived?

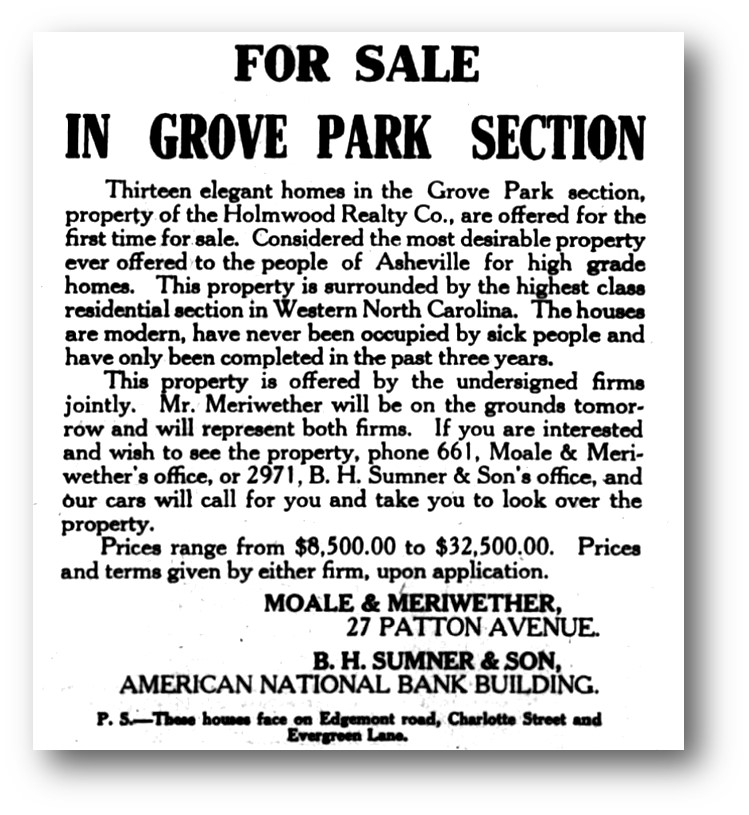

Although the Chapman houses were initially rented out, in 1919 Chapman decided to put them up for sell. In June of 1919, a large advertisement announced that, “Thirteen elegant homes in the Grove Park section, property of the Holmwood Realty Co., are offered for the first time for sale.”[48] The advertisement noted that their “Prices range from $8,500 to $32,500”.[49] Interestingly, the first of the Chapman houses to be sold was the house on Lot. No. 1, addressed as 1 Evergreen Lane, sold to Elizabeth S. Weeks in September of 1919.[50] Miss Weeks moved into the house with her 84 year old father, Horace S. Weeks, who sadly died in the house just a month later.[51]

The origins of the house at 1 Evergreen Lane, was the product of development and re-development, and of a unique collaborative enterprise between developer and an early design/build firm, which was also a manufacturer. This collaborative effort was a precursor to today’s modular and manufactured houses. But more important to us, this creative collaboration produced many houses in Holmwood Park and Kenilworth, and perhaps other neighborhoods, all of which contribute to the character and charm of Asheville’s historic neighborhoods to this day.

Photo & Image Credits: (Note: All cropping and captions by author)

1 Evergreen Lane- Courtesy Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

Glenverloch Advertisement–The Semi-Weekly Asheville Citizen, November 19, 1885, page 1.-newspapers.com

Sunset Mountain Land Company Map-MAP 401-Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

1891 Bird’s Eye View of Asheville- Ruger & Stoner, and Burleigh Litho. Bird’s-Eye View of the City of Asheville, North Carolina. [Madison, Wis, 1891] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694894/

Photo of Macon Avenue Trolley line– Image # A413-4- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Photo of Swannanoa Country Club Clubhouse & Golf Station- Image # A121-4- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

1903 Map of Asheville & Buncombe County- MAP 501- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Plats of Proximity Park- 06/01/1907 Proximity Park-PLAT CHARLOTTE STREET Db. 8/82 AND 06/22/1907 Db. 150/194.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Photo of Edgemont Road & Golf Station- Image # K666-8- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Photo of S. F. Chapman- Image # B551-11- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Plat of Holmwood Realty Company- 12/27/1917 Holmwood Realty PLAT CHARLOTTE STREET Db. 198/166.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Advert for Carpenters at Edgemont Road-Asheville Citizen-Times, May 13, 1917, page 24.-newspapers.com.

Advert for Sale of Holmwood Park Houses- Asheville Citizen-Times, June 10, 1917, page 7.-newspapers.com.

[1] Early Twentieth Century Suburbs in North Carolina: Essays on History, Architecture and Planning, page 4.

[2] Actually reported as 10, 235 residents-“Table 5- Populations of the Incorporated Cities, Towns, and Villages of North Carolina 1890-1900”, Bulletin 39. POPULATION OF NORTH CAROLINA BY MINOR CIVIL DIVISIONS: 1890 AND 1900, page 13. https://www2.census.gov › bulletins › demographic

[3] Early Twentieth Century Suburbs in North Carolina: Essays on History, Architecture and Planning. Edited By Catherine W. Bishir and Lawrence S. Earley. (Raleigh, NC: Archaeology and Historic Preservation Section, Division of Archives and History, N.C. Dept. of Cultural Resources, 1985), page 3.

[4] Asheville Citizen-Times, February 5, 1898, page 6.

[5] “Asheville Town in 1842- Justice Summey Gives Many Interesting Facts”, Asheville Citizen-Times, September 25, 1900, page 5.

[6] Asheville Citizen-Times, May 27, 1885, page 1.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Glenverloch” sometimes spelled “Glenvarloch” was no doubt taken from a famous character in two Waverly novels by Sir Walter Scott. The fictional character, Nigel Olifaunt, is a nobleman titled, “Lord Glenvarloch”.

[9] Asheville Citizen-Times, August 19, 1886, page 4.

[10] H. A. & Jennie H. Gudger to W. B. Gwynn & George M. Swain 96 ACRES CHARLOTTE ST & SUNSET DR, Db. 60/2.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[11] “A Grand Scheme-A Turnpike and Railway To the Top of Craggy-Development of Our Magnificent Mountain Lands”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 5, 1889, page 1.

[12] Ibid.

[13] The Asheville Democrat, August 21, 1890, page 1.

[14] Ibid.

[15] The Progressive Farmer, Winston-Salem, NC, July 29, 1890, page 1.

[16] The Craggy Mountain Line website, “History-Howland Lines”- https://craggymountainline.com/history/2012/the-howland-lines/

[17] Asheville Citizen-Times, January 30, 1891, page 4.

[18] Session Laws and Resolutions Passed by the General Assembly, North Carolina, 1891, Chapter 292-293, pages 1314-1315.

[19] Asheville Citizen-Times, September 30, 1891, page 3.

[20] Asheville Citizen-Times, April 9, 1892, page 4.

[21] Asheville Citizen-Times, July 2, 1892, page 1.

[22] The Craggy Mountain Line website, “History-Howland Lines”- https://craggymountainline.com/history/2012/the-howland-lines/

[23] “Proximity Park Historic District”, Asheville, Buncombe County, BN1250 -Nomination to the National Register of Historic Places, Nomination prepared by Helen Purdum and Kathryn Scott, Listed 10/8/2008., Section 8 page 30.

[24] “New Golf Links at Sunset Mountain”, Asheville Daily Gazette, June 11, 1898, page 5.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Asheville Citizen-Times, October 14, 1898, page 1

[28] Ibid.

[29] The Craggy Mountain Line website, “History-Howland Lines”- https://craggymountainline.com/history/2012/the-howland-lines/

[30] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 1, 1900, page 1

[31] “Proximity Park Historic District”, Asheville, Buncombe County, BN1250 -Nomination to the National Register of Historic Places, Nomination prepared by Helen Purdum and Kathryn Scott, Listed 10/8/2008., Section 8 page 33.

[32] Asheville Citizen-Times, February 15, 1907, page 2.

[33] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 21, 1907, page 5.

[34] 07/06/1907 Proximity Park Company to Asheville Rapid transit Company RIGHT OF WAY Db. 150/239.

[35] Asheville Gazette News, May 31, 1910, page 7.

[36] 05/11/1911 Proximity Park Company to Carl V. Reynolds, Trustee CHARLOTTE STREET Db. 172/303.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds

[37] 07/20/1914 Carl V. Reynolds, Trustee & Directors of Proximity Park Company to Annie R. Burroughs and Minnie R. Chapman CHARLOTTE STREET, Db. 197/321.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[38] Asheville Citizen-Times, September 30, 1916, page 1.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] “Chapman Rites Today at Trinity”, Asheville Citizen-Times, April 23, 1930, page 8.

[42] 08/25/1916 Holmwood Realty Company, INC, Db. C004/250.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[43] The Wilmington Dispatch, Wilmington, Delaware, January 22, 1916, page 6.

[44] Asheville Citizen-Times, March 13, 1916, page 12.

[45] Asheville Citizen-Times, May 13, 1917, page 24.

[46] Asheville Citizen-Times, October 14, 1917, page 23.

[47] Asheville Citzen-Times, November 11, 1917, page 23.

[48] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 10, 1919, page 7.

[49] Ibid.

[50] 08/13/1919 (rec’d-09/16/1919) Holmwood Realty to Elizabeth S. Weeks LOT 1 BK 198 P 166 Db. 234/228.

[51] “Horace S. Weeks Died Yesterday”, Asheville Citizen-Times, October 24, 1919, page 16.