By Dale Wayne Slusser

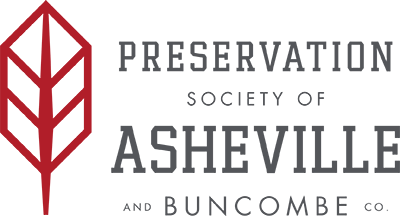

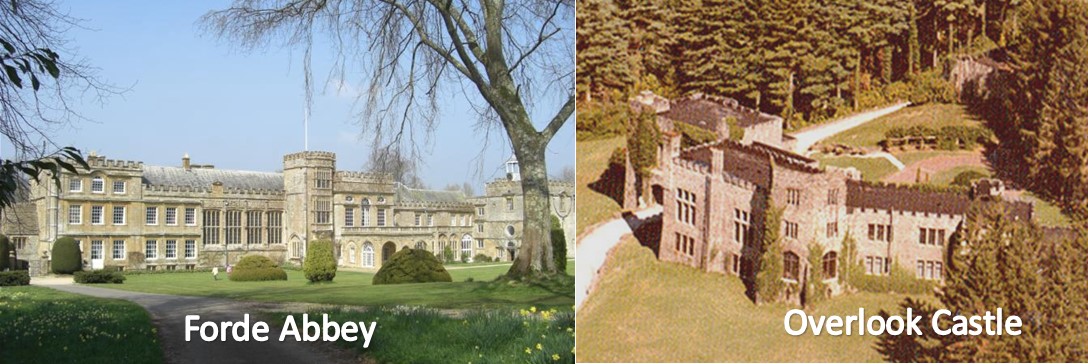

On May 24, 1914, the Charlotte Observer reported the following news from Asheville: “Work on the stone castle which Fred L. Seely is building on the brow of Overlook Mountain has been resumed and a force of 30 workmen is now engaged in erecting the walls of what is expected to be one of the finest private homes in the South. The building follows closely the design of Forde Abbey, England, a stone castle of the year 1850 [1350] and will present the appearance of the old feudal castles of the Fourteenth Century.” This grand residence, which Seely simply named “Overlook”, is also generally known as “Seely’s Castle”. Much has already been written about Seely’s Castle, both fact and fiction (suspected haunting), however, I would like to examine the residence from an architectural viewpoint, looking at its style, possible precedents, and its comparison to Forde Abbey, which inspired its creation. But first, let us look briefly at Fred Seely and what led up to the building of his mountaintop castle.

Fred Loring Seely was born in 1871 in Fort Monmouth, N.J., the son of Uriah and Nancy Hopping Seely. At the age of thirteen, Fred was hired by a pharmaceutical firm in New York as an office boy. He began the study of pharmacy, both on the job and through the New College of Pharmacy. Later he joined Parke-Davis and Company of Detroit as one of eight employees making up the first formal pharmaceutical firm in the country. When he was 24 years of age, he was promoted to be the Head of the tablet manufacturing division of Parke-Davis. He developed a machine to make pills or tablets and another to count and package them. In 1897, Edwin W. Grove, founder of the Paris Medicine Company of St. Louis and a customer of Parke-Davis, visited Parke-Davis seeking information which he hoped would help perfect his Laxative Bromo Quinine tablets. He was referred to Fred Seely. Seely not only had some excellent suggestions for Grove, but he also “wined and dined” Grove for the next couple of days. Grove was so impressed with Seely’s suggestions, that shortly thereafter, Grove hired Seely to manage a small experimental manufacturing laboratory that he was opening in Asheville. Grove had come to Asheville in hopes that it would improve his health.[1]

The July 14, 1898 edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times published the following notice: “E. W. Grove, president of the Paris Medicine Company has leased the old cigarette factory at the corner of South Main and Atkins streets, the building to be used as a location for the manufacture of Bromo-Quinine. F. L. Seely, an expert chemist, will have charge of the Asheville branch of the company’s business. Machinery has been ordered and operations will begin, it is thought, in about six weeks.”[2] Shortly after taking over Grove’s Asheville factory, Seely designed, developed and patented a device (machine) for “measuring, delivering, and wrapping powders”.[3] Seely was not only a chemist, but an engineer and an adroit businessman. Also, in 1898 Seely married Evelyn Grove, E. W. Grove’s daughter. The couple remained living in St. Louis, while Fred commuted to Asheville on occasion.

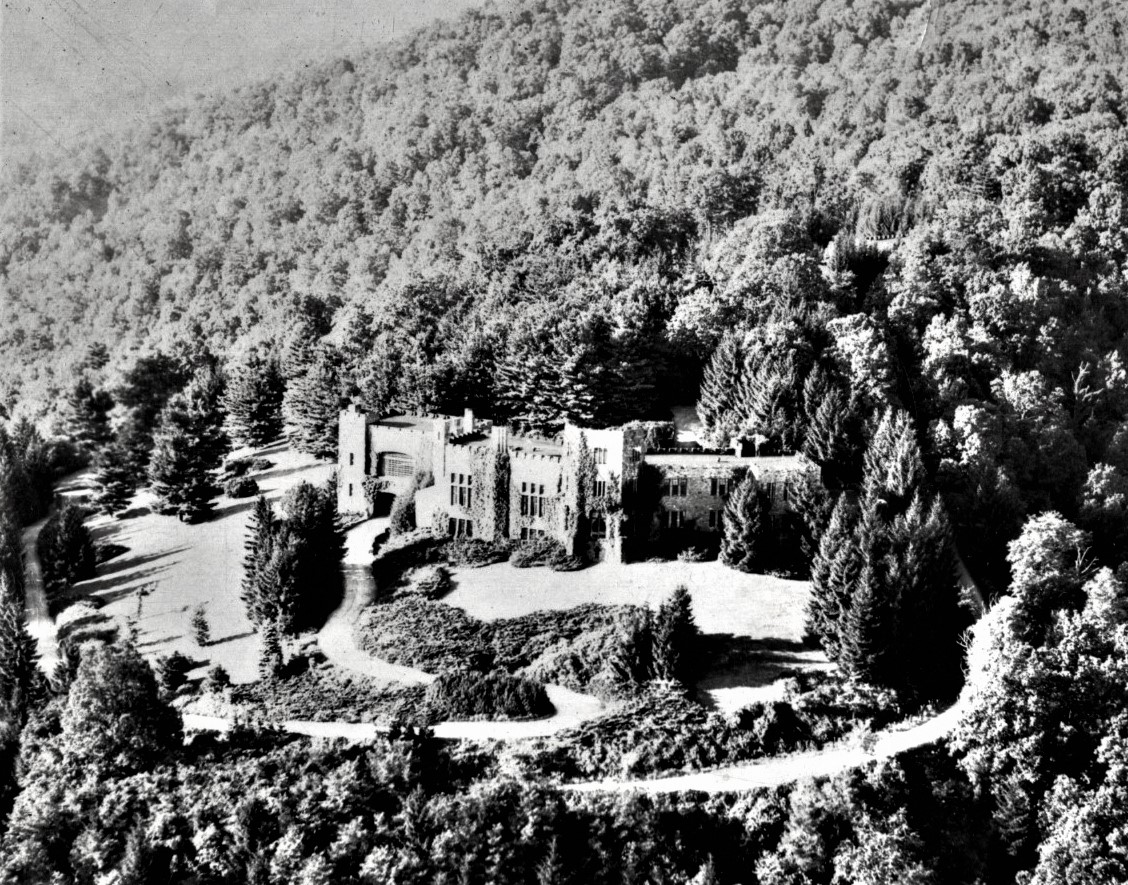

By 1900, the Asheville factory was closed and Seely, who was then the Secretary-Treasurer of the Paris Medicine Company, was transferred back to the St. Louis headquarters. Seely’s talents and industriousness had made him both successful and rich. In fact, in the 1900 US Census, he reported his occupation as “Financier”. In 1901, Mr. & Mrs. Seely embarked on a worldwide trip. First to Java and India to scout out and investigate possible quinine sources, then on to the Holy Land and home via stops in Europe. Perhaps it was then that Seely visited Forde Abbey, although he was an inveterate traveler during those early years, so it could have been on a subsequent trip. But then in 1902, surprisingly (to the pharmaceutical world), at 30 years of age, Fred Loring Seely decided to retire to pursue the study of Law at Yale University. His decision was widely publicized in the newspapers and trade journals. Accompanied by a photo, the September 18, 1902 issue of The Pharmaceutical Era magazine announced that “Fred L. Seely Deserts Business For Law Books”. [4] Despite his highly publicized plans, the fact of the matter is that, in the end, although Fred Seely did retire from the pharmaceutical business in 1902, he apparently never attended Yale, nor studied law, although he did spend a year living in Princeton taking a few general education courses.[5]

In 1905, Seely’s father-in-law, E. W. Grove, persuaded Seely to move to Atlanta, where in partnership with John Temple Graves, he founded an afternoon newspaper, named The Georgian. In 1907, John Temple Graves, moved to New York, leaving Seely totally in charge of the flourishing newspaper. At the time, it was reported by a perceptive and prophetic reporter that because Seely “has succeeded in everything he has ever undertaken”[6] that he would soon be a leading publisher, “in the front rank of southern publishers.”[7] As a publisher, Seely became a noted editorialist, and The Georgian was so successful that in 1912, when Seely decided to sell his newspaper, he attracted the eye of the top notch titan of publishing, William Randolph Hearst. In February of 1912, Hearst purchased The Atlanta Georgian for $31,300.[8]

In 1912, immediately after the sale of his newspaper, Seely moved his family to Asheville to help his father-in-law, E. W. Grove, who had previously relocated to Asheville, where he had begun what would become his massive and numerous real estate development projects. Grove intended that his “Grove Park” development at the north end of Charlotte Street in northeast Asheville would attract high-end clients, and as an incentive to attract wealthy clients, Grove decided to build a first-class hotel and country-club as its centerpiece. Apparently, Grove had persuaded Seely to sell the newspaper so that Seely could take over the construction and development of Grove’s proposed “Grove Park Inn”. The story of the building of the Grove Park Inn has been told by others[9], but suffice it to say that its creation, construction, management, and development and ultimate success can be almost entirely attributed to Fred Seely. As the story goes, although Grove and Seely had solicited numerous proposals and renderings from leading architects of the day for the design of the new Grove Park Inn, none of them met with Grove’s approval. In the end, it was Seely’s amateur design proposal that caught the attention of his father-in-law. Seely’s design satisfied Grove’s original intent to build a grand rustic-style hotel resembling Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone National Park. To provide the professional design and engineering for the new “fireproof” hotel, Seely chose architectural engineer, Groce W. McKibbin of the Southern Ferro-Concrete Company of Atlanta.[10] The construction of the massive Inn was competed in a little over one year and was opened on July 1, 1913, under the adroit management of Fred L. Seely.

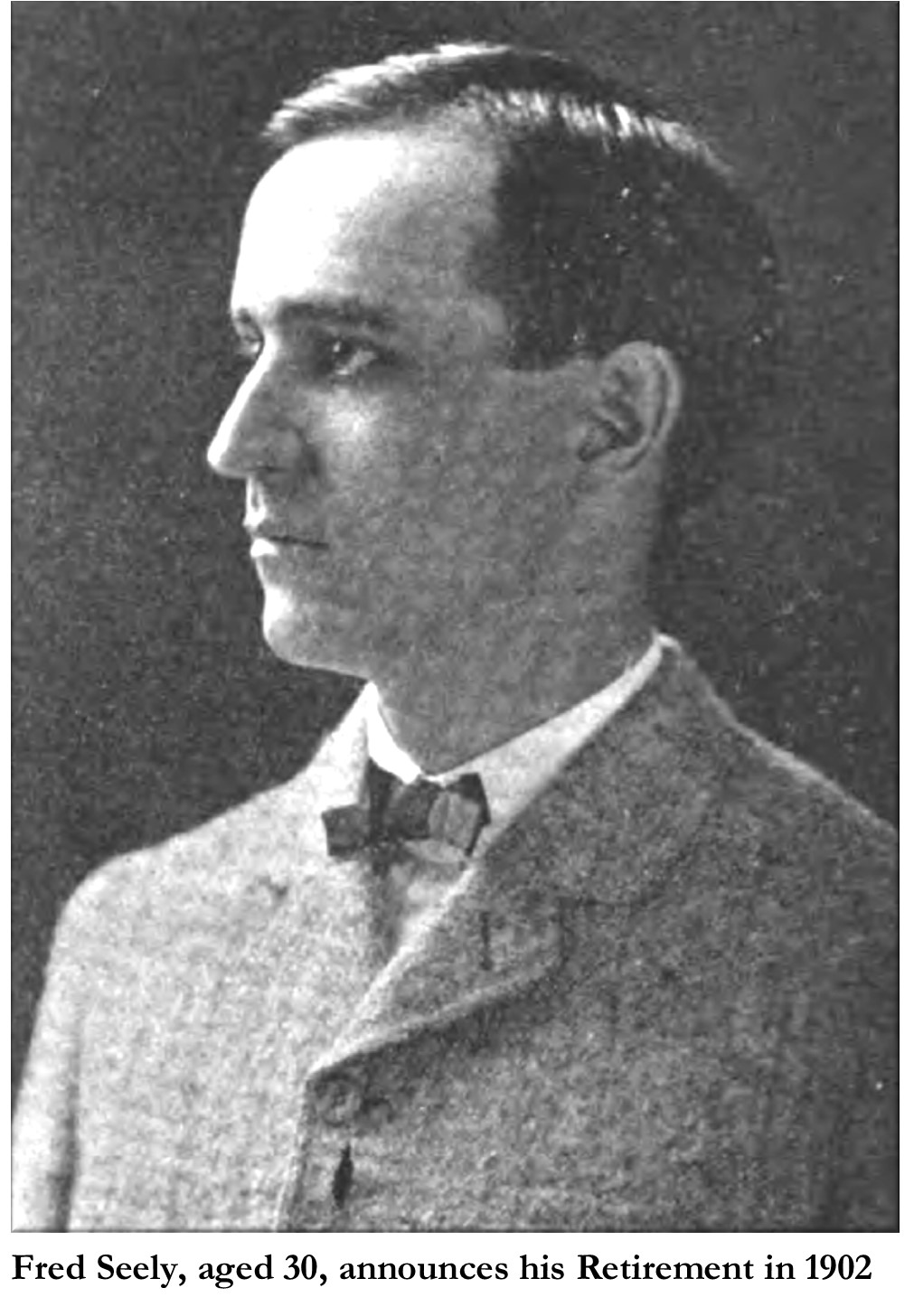

As the construction was nearing completion on the Grove Park Inn, it was announced in the January 17, 1913 edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times that: “Ground has been broken at Overlook park, preparatory to the laying of the foundation for the residence of Fred L. Seely, work upon which will be started immediately.”[11] Overlook Park was the former recreation park on the top of Sunset Mountain, overlooking Chunn’s Cove, which had been established in 1900 by R. S. Howland.[12] E. W. Grove purchased the park in the Spring of 1910,[13] and within a year he had closed the park to the public. In the summer of 1911, Grove remodeled the former park pavilion into a temporary residence for Fred Seely and his family.[14] The Seelys occupied their bungalow for the ensuing years during construction of their new residence. Although the site preparation and foundations were started in January of 1913, it was not until the Spring of 1914 that the actual building permit was issued, and construction begun in earnest.[15] And although the construction timeline in 1913 was predicted as one year, the Seelys were not able to occupy their new stone castle until the end of 1916.[16]

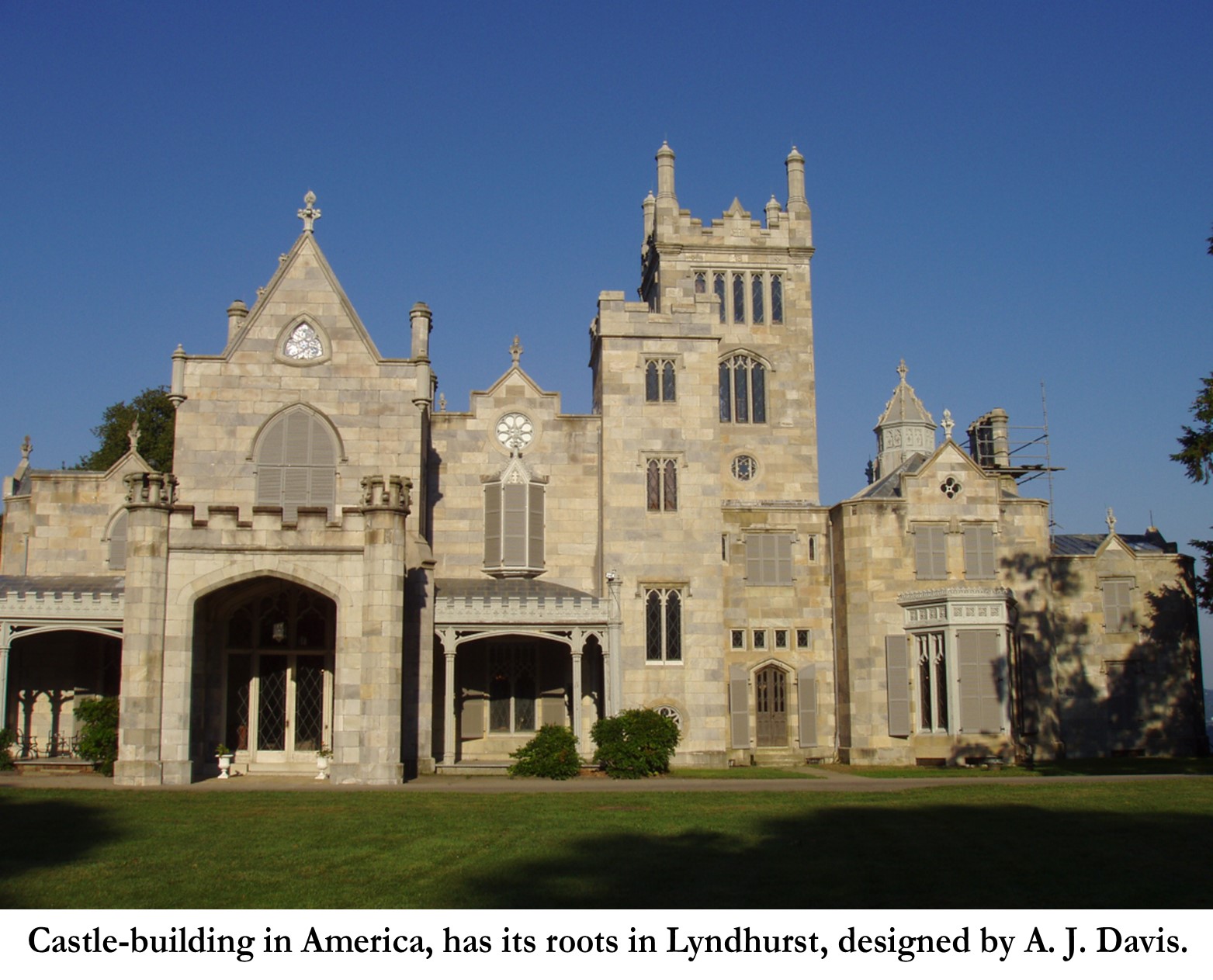

Modern-day (twentieth and twenty-first century) castle-building has its earliest roots in the Gothic Revival Movement started in England in the mid-eighteenth century when Horace Walpole built his mock-Gothic house, Strawberry Hill, in Twickenham, England, borrowing its design and detailing from medieval Gothic architecture. Although Classicism reigned in eighteenth-century England (and it’s colonies-like us), Gothic-revival architecture, called “Gothick”, began being popularized for domestic architecture by builder’s and architects through architectural pattern books such as Batty Langley’s (also from Twickenham) Ancient Architecture, Restored, and Improved, published in 1742 and reissued in 1747 as Gothic Architecture, Improved by Rules and Proportions.[17] However, modern-day castle-building has its most direct roots in the Victorian Romantic Revival movement. “It is really only after 1840 that the Gothic Revival began to gather steam” writes author David Ross[18]. In England, men like A. W. Pugin and John Ruskin promoted Gothic-revival architecture through their writings, such as Ruskin’s publications, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and the Stones of Venice (1851).

In America, the primary promoter of Gothic-revival architecture for domestic architecture was architect, Alexander Jackson Davis. In an interesting twist, the designs of A. J. Davis, were first promoted (and thus proliferated) through the publications of a landscape architect named, A. J. Downing! Andrew Jackson Downing’s publications: Cottage Residences (1842) and The Architecture of Country Houses (1850) which featured house designs mostly by architect Alexander Jackson Davis, would greatly impact the design of residences across the country. Using the revolutionary ideas of the Picturesque Aesthetic, and the romantic English cottage, Downing’s and Davis’ designs were adapted for American houses, and included the integration of landscaping, interior decoration, furniture and even heating and ventilation issues. However, Alexander Jackson Davis, on his own, promoted the Gothic Revival through his individual commissions, such as the notable, stone gothic mansion “Lyndhurst” first designed by Davis for William Paulding in 1838, and expanded with further Davis designs for its second owner, George Merritt in 1864.[19]

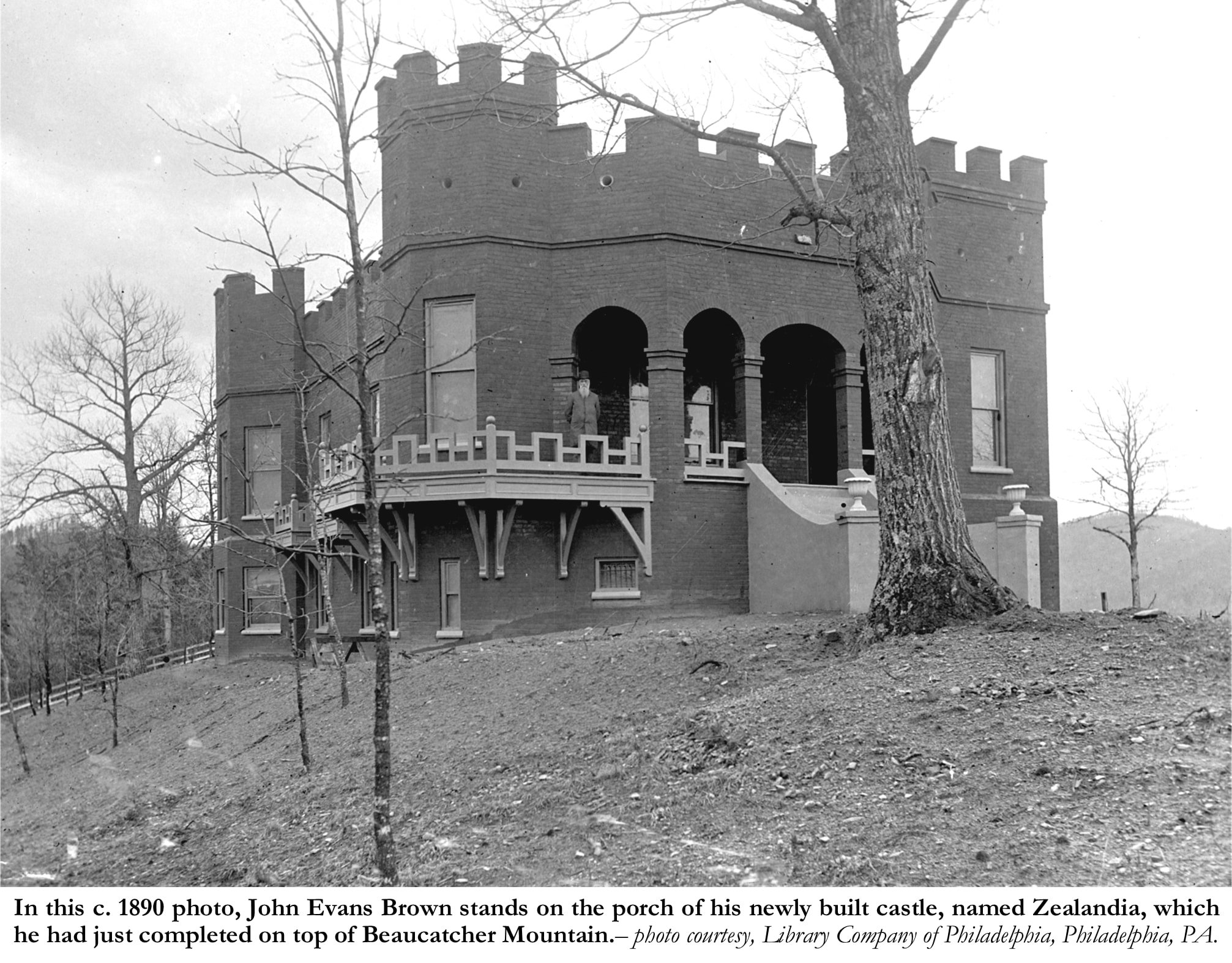

Seely’s Castle was not the first “castle” built in Asheville. In 1889, shortly after returning from living in New Zealand for twenty years, John Evans Brown purchased five acres on top of Beaucatcher Mountain, just south of where Seely’s castle would later be built. On his newly purchased site, Brown erected Zealandia, a castellated brick Gothic Revival castle, of which it was reported that, “Mőro castle of Havana, being somewhat suggestive of the plan.”[20] Zealandia, which survives, was greatly enlarged by Phillip S. Henry, who had purchased the castle in 1904. It was probably around 1907-08, when during its expansion, that the original brick walls were covered with pebble-dash stucco.

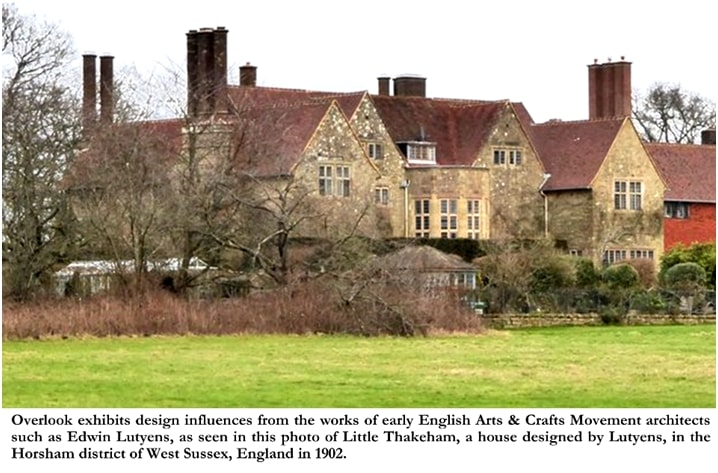

We can also attribute Seely’s Medieval Gothic design to the work of Victorian-Edwardian English Arts & Crafts architects such as Norman Shaw, Phillip Webb, Edwin Lutyens, C. F. A. Voysey, and Baillie Scott. In reaction to the excesses of the industrial-revolution with its mass-produced goods, early proponents of the Arts & Crafts movement sought to bring back hand-craftmanship and creative design to the field of art, architecture, and the decorative arts. For their inspiration they hearkened back to the work of the medieval guild craftsmen and Gothic architecture. “The early writings of the Arts and Crafts movement exude praise for the Gothic in the face of the then-current affection for the classical,”[21] writes architectural historian/author Beth Dunlop. The medieval influences were manifested in the work of Lutyens, Voysey and Scott by the use of asymmetry, towered and windowed bays, leaded glass windows, stonework and masonry exteriors, baronial hall-styled rooms, Tudor-detailing, and beamed ceilings. These influences also certainly informed the design of Overlook Castle.

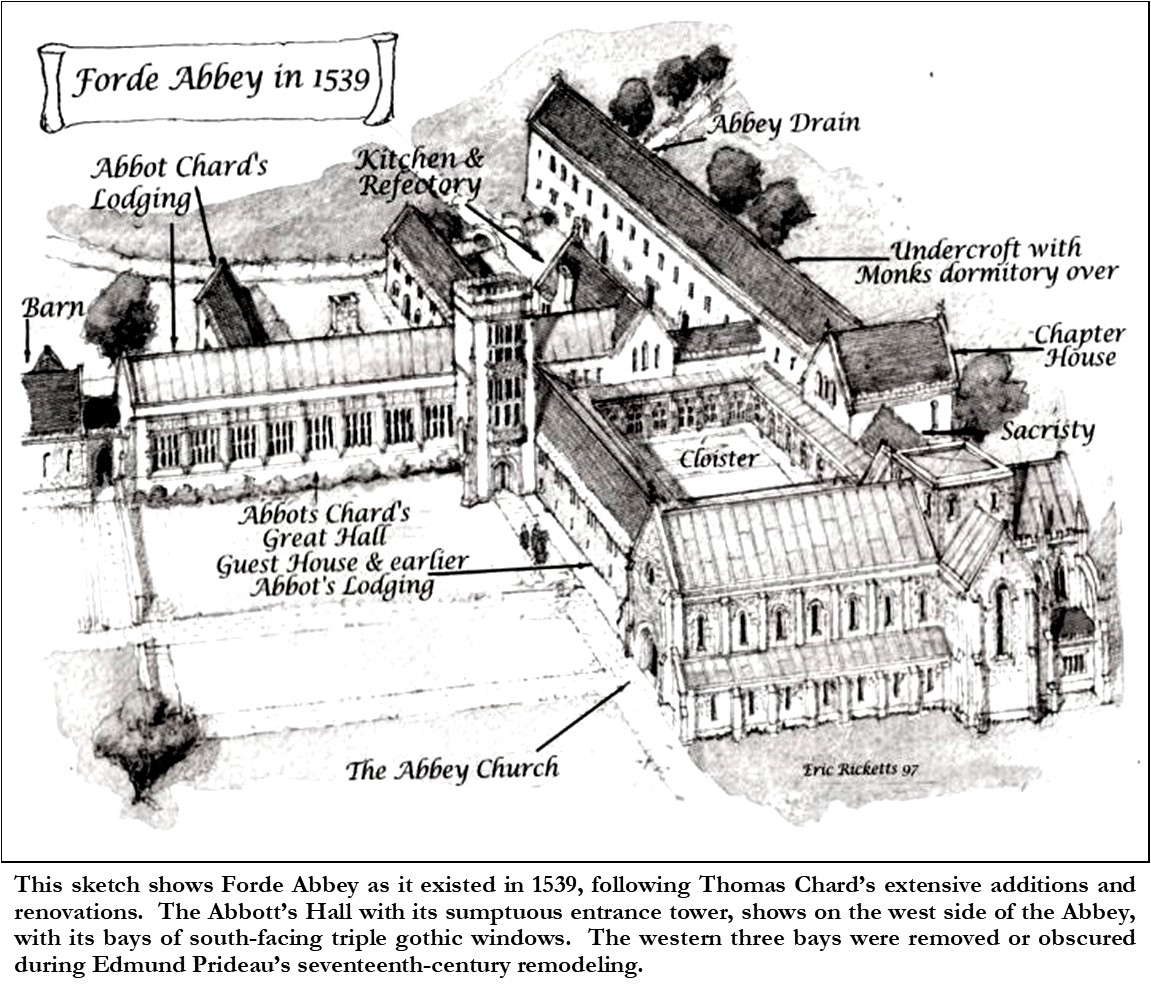

However, we know from the contemporary newspaper reports, published when it was being built, that the primary design influences for Seely’s stone castle, was from Forde Abbey, an actual medieval building. Forde Abbey, a privately owned former Cistercian monastery in Dorset, England, was founded in the twelfth century and flourished as a monastery for four hundred years. The monastery was dissolved in 1539, and Forde Abbey was turned over to the Crown, as rental income. For the next hundred years the property was owned by a succession of absentee landlords, who farmed the lands, until 1649 when it was purchased by Edmund Prideaux a Member of Parliament. Prideaux was responsible for transforming Forde Abbey from a monastery into a private home.[22]

Seely’s Castle, Overlook, has been purported to be a copy or replica of Forde Abbey, however, it is only “somewhat suggestive” of Forde Abbey. I will say though, that Overlook is much more “suggestive” of Forde Abbey than Zealandia is of Mőro castle, and with a comparison and study of its details, it becomes obvious to the perceptive observer, that Overlook was designed using Forde Abbey for its primary design influences. Take Forde Abbey and transpose it to the twentieth century, and set it on a mountaintop, instead of in a meadow by the river, add modern amenities and the result is Seely’s Castle! The design of Overlook is a result of using a design influence like Forde Abbey in combination with a specific site, timeframe, type of construction, modern building technologies, use of local building materials, and the client’s (Seely’s) design program (number, types, and uses of proposed spaces).

The most obvious resemblance of Overlook Castle to Forde Abbey is the blockish massing of the castle and its stone castellated walls. This rectilinear shape of Overlook Castle, at first looks like it owes its design to the tenets of Art Deco design, but in fact its roots are in the Medieval design of Forde Abbey. Whereas the stone exterior walls of Forde Abbey are of smooth ashlar stone, the walls of Overlook are a unique combination of elongated (almost brick-shaped) square coursed rubble interspersed with standing rubble stones. This is another example of transposition, as dressed ashlar stone would have been more expensive to use for Overlook and would not have fit into the rustic-mountain esthetic which was becoming popular in early twentieth-century Western North Carolina.

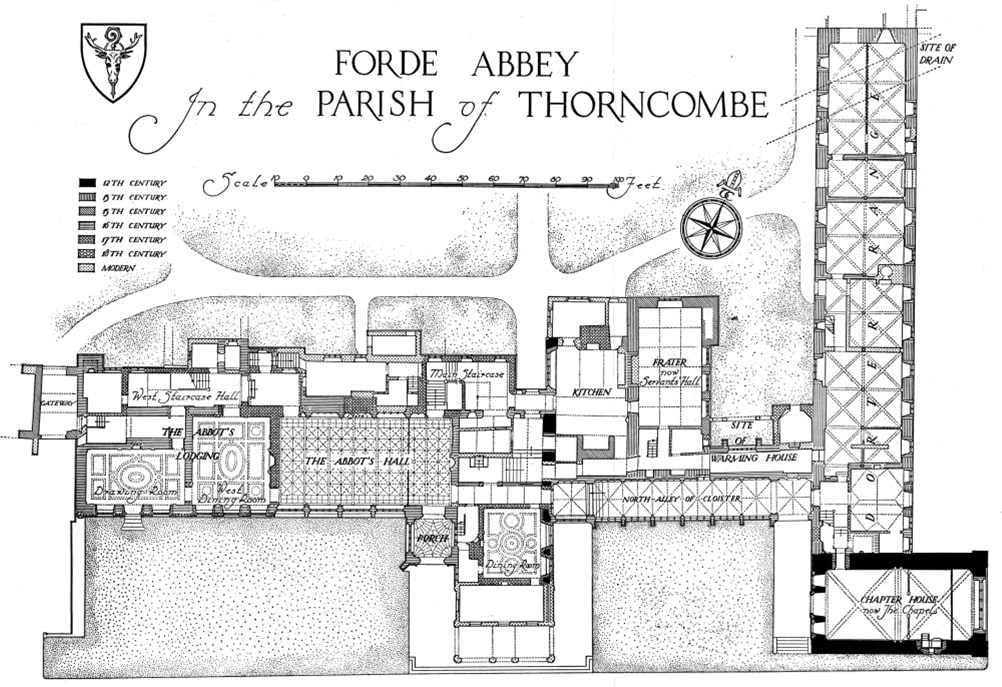

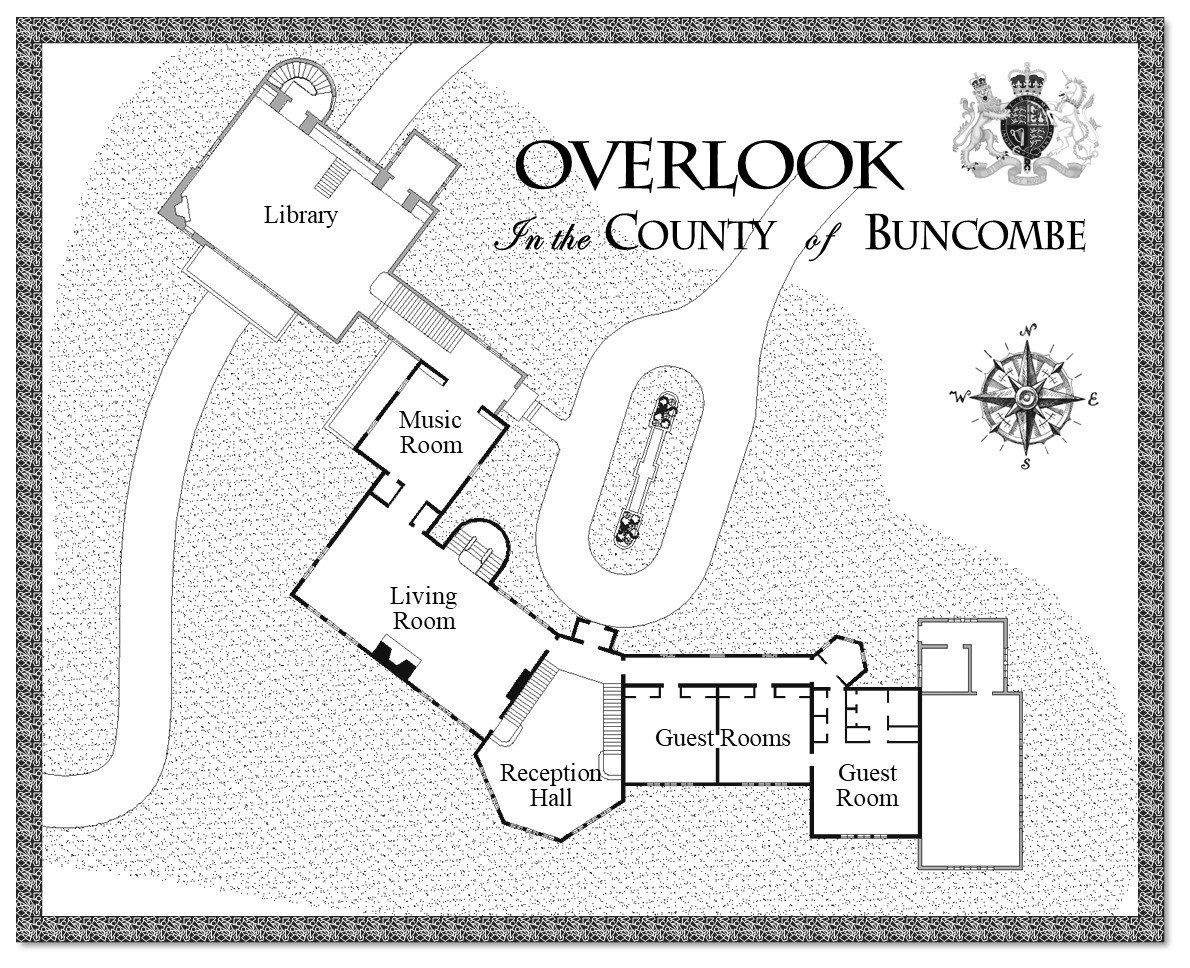

Overlook and Forde Abbey share a similar floor plan arrangement. Both plans give the appearance of and in fact are a result of the attrition of numerous additions over the years. Like Forde Abbey, the principal rooms of Overlook are strung out on an east-west axis and are located in the center and west side of the first floor, with all the principal rooms having their main view-windows on the south elevation. However, their main views are remarkably different, as the Abbey sits on the valley floor next to the River Axe, with its southerly view looking out over a formal garden, whereas Overlook, being sited on top of Sunset Mountain, has its view down to the Chunn’s Cove valley below. Overlook’s floor plan is angled to maximize the view, whereas Forde Abbey’s floor plan is all right angles.

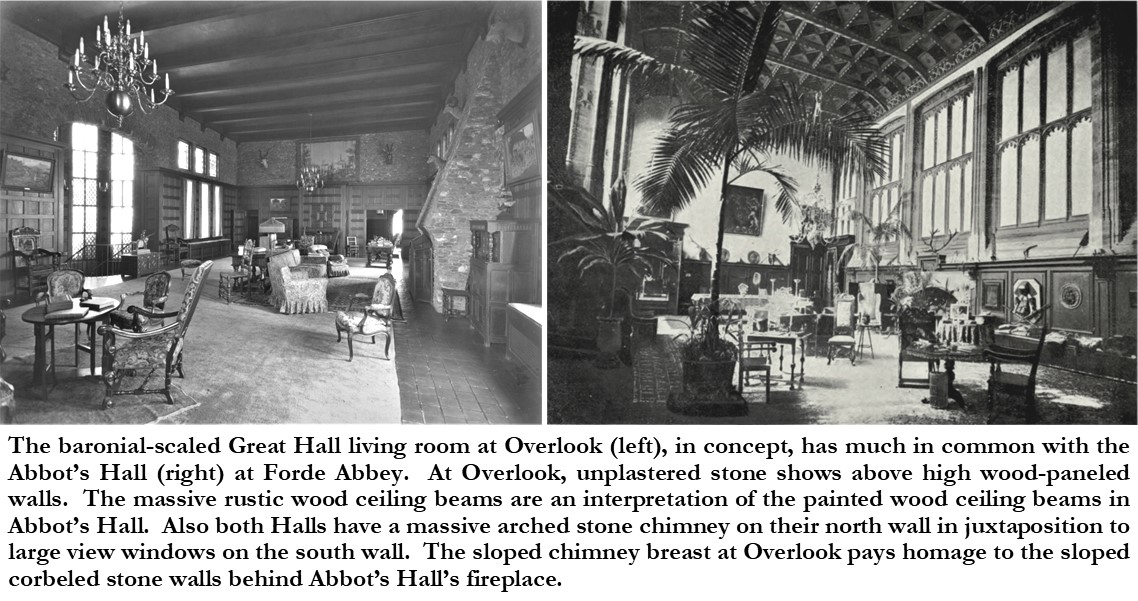

Overlook Castle’s most obvious connection to Forde Abbey is the design of its medieval- Great Hall-styled living room. In its baronial scale, style, and details, one can see that Overlook’s living room was inspired by Abbot’s Hall at Forde Abbey. Abbots Hall was built by sixteenth century Cistercian Abbot, Thomas Chard, whose “extravagant and beautiful additions to the monastery were begun in 1522”[23]. As the centerpiece of his new lavish “Abbot’s Lodgings”, Chard’s Great Hall, which functioned as his living room, was “some 80 feet long, 28 feet wide, and 28 feet high extending over six bays, one of the largest in southern England.”[24] Abbot’s Hall was entered through a sumptuous entrance tower (which Chard also built) at its southeast corner. As originally built, several bays of south-facing triple gothic windows, extended west from the tower. The western three bays were removed or obscured during Edmund Prideau’s seventeenth-century remodeling.

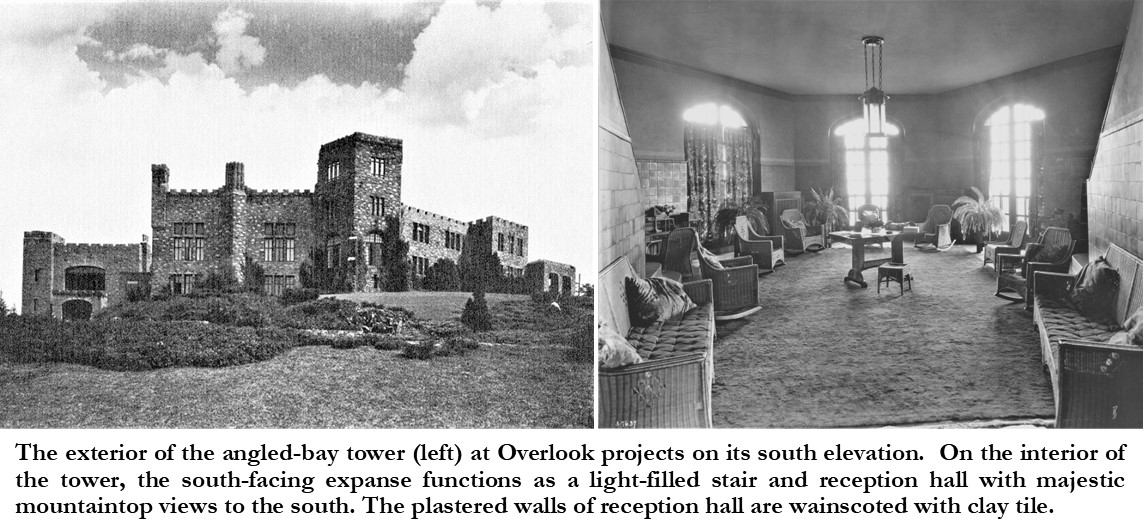

The main entrance to Overlook, and access to its Great Hall-living room is also through a tower, albeit its tower has striking differences from Abbot Chard’s tower at Forde Abbey. The first obvious difference is that Overlook’s tower is wedge shaped on the interior, but on the exterior, it appears to have been intended to be octagonal, however, since the third story of the tower was never completed, its appearance is that of an angled bay. Although the tower at Overlook is prominent on its south elevation, like the tower at Forde Abbey, its entrance is actually on its north side at the narrow end of its wedged shape. This difference was no doubt necessitated by its steep mountain site where the grade slopes away from north to south, making an at or near grade entrance most convenient on its north elevation. This also may have been a component of its design program, as this allows for its south-facing expanse to function as a light-filled reception hall with majestic mountaintop views.

The interior design of the baronial-scaled Great Hall living room at Overlook has perhaps the most recognizable connection to Forde Abbey, although there are also obvious differences. The Great Hall, though not as long in length, is in scale with Abbot’s Hall, measuring 30 feet wide by 57 feet long with a 32 feet high ceiling. At Overlook, un-plastered stone shows above high wood-paneled walls. The massive rustic wood ceiling beams are an interpretation of the painted wood ceiling beams in Abbot’s Hall. Also, both Halls have a massive arched stone chimney on their north wall in juxtaposition to large view windows on the south wall. The sloped chimney breast at Overlook pays homage to the sloped corbeled stone walls behind Abbot’s Hall’s fireplace. A unique feature specific to the Great Hall at Overlook is the curved stair on the north wall that sweeps down to the ground floor dining room in a projecting stone towered bay.

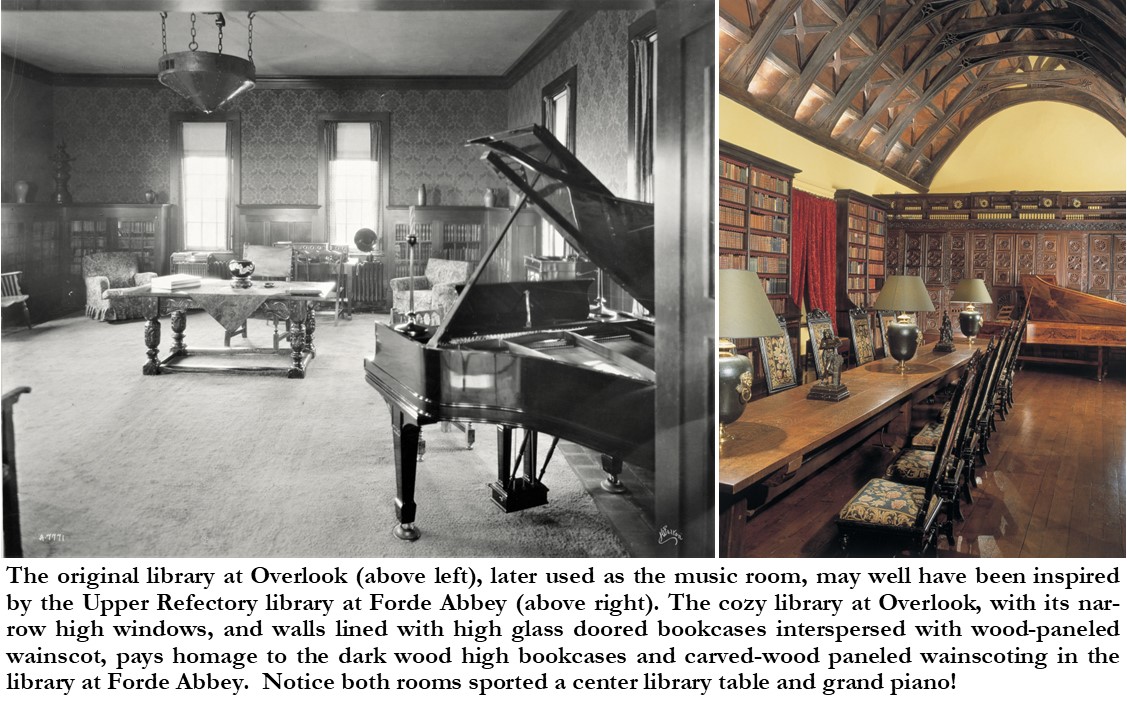

The original library at Overlook was accessed through the west-end of the north wall of the Great Hall. This room now functions as a music room and thoroughfare from the Great Hall to the “new” library, added in 1924. Although certainly smaller in scale, Overlook’s original library may well have been inspired by the library at Forde Abbey. The library at Forde Abbey was originally The Upper Refectory, a dining room allotted to meat-eating monks who were required to dine separately from their vegetarian colleagues (the vegetarian monks ate in the Lower Refectory). In the seventh-century, owner Edmund Prideaux added a minstrel gallery to room. Herbert Evans, who inherited Forde Abbey from his father Bertram Evans, transformed the former refectory/hayloft into a library in the mid-nineteenth century. The cozy library at Overlook, with its narrow high windows, and walls lined with high glass doored bookcases interspersed with wood-paneled wainscot, pays homage to the dark wood high bookcases and carved-wood paneled wainscoting in the library at Forde Abbey.

The “new” library at Overlook, added in 1924, which measured 40 feet wide by 50 feet long, is almost twice as large as the original library. Solid double-height mahogany bookshelves cover the entire north wall, with a massive six-glass-paneled folding doors with an arched glass transom above, on its opposing southern wall. The glass folding doors, which have brass fixtures, operate on ball rollers that enable them to fold back like a screen, opening to a small balcony. The leaded glass doors, made by Hope Casement Company of England, were quite innovative for their time, and are much like the modern folding glass doors we have today.

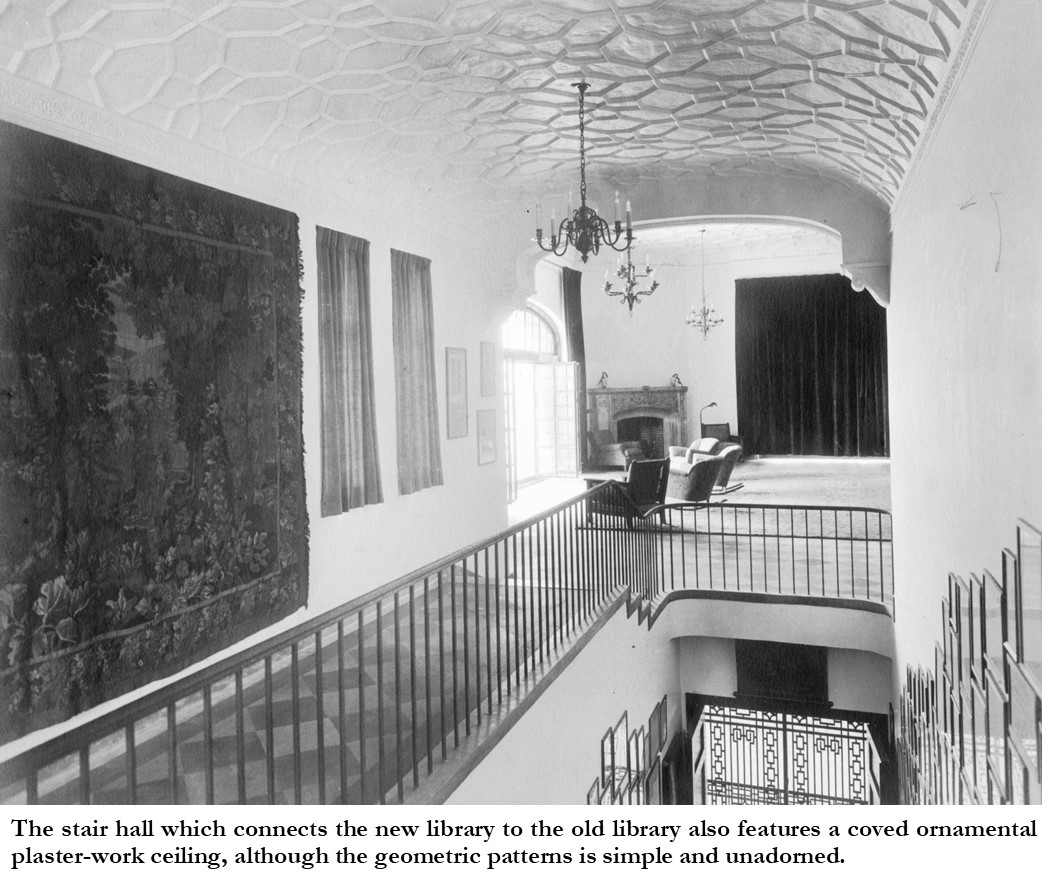

The design of the new library probably took most of its design influences from the already existing part of Overlook, however, one detail that may have been influenced by, or is at least characteristic of Forde Abbey is the ornamental plaster-work ceiling. Although heavier and highly more ornamental than those at Overlook, the ceilings in the formal gathering rooms (Drawing Room, Dining Room, West Dining Room & Main Stair) at Forde Abbey all feature molded plasterwork ceilings. The ceiling plasterwork in the new library at Overbook is in a geometric pattern which features rows of alternating large molded barbed-quatrefoils connected in each direction with molded square-crosses. In the recesses formed by the crosses are square foliage ornaments. The recesses of the quatrefoils each contain a family crest either of the Seely, More, or Leslie families. The stair hall which connects the new library to the old library also features a coved ornamental plaster-work ceiling, although the geometric patterns is simple and unadorned.

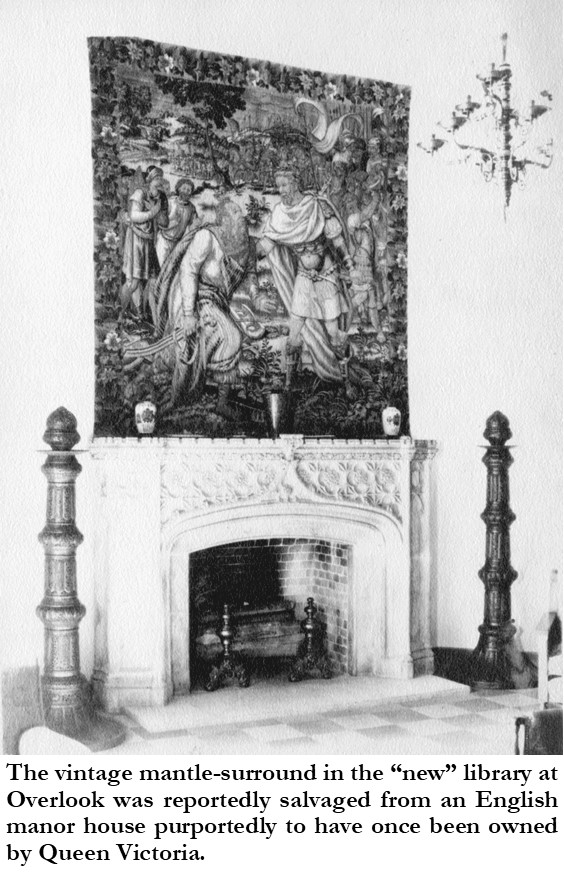

Another architectural feature of the new library at Overbrook is the carved stone Tudor mantle-surround on the angled fireplace in the southwest corner of the room. The vintage mantle-surround was reportedly salvaged from an English manor house purportedly to have once been owned by Queen Victoria. Although it does not directly match any mantle-surround at Forde Abbey, it is certainly in the same Gothic-Tudor style, and its castellated top is certainly consistent with the Gothic-Castle design theme of Overlook Castle.

In 1949, seven years after the death of Fred Seely, Evelyn Seely sold Overlook to Asheville-Biltmore College, with the stipulation that the residence building be named “Seely Hall”. The college occupied the property until 1961 when they then moved to their new campus across town (now the campus of UNCA). Two years later, a developer named William W. Bond, Jr. purchased the property and erected a high-rise apartment building on a portion of the land. In 1965, the developer sold the remaining land, including Overlook Castle, to Jerry Sternberg, who subsequently took on the momentous task of restoring the house, which had fallen into ruin since the college had vacated the building. Sternberg restored the Castle back to a family residence. In 1976, the Sternbergs offered the property for sale, but when no qualified buyer could be found, they donated the property to a charitable organization for tax purposes. This organization in turn sold the property to Nicholas & Patricia Cassizzi in 1978 who used the property for a new Christian ministry which they called Overlook Christian Ministries.[25] In 1983, Overlook Christian Ministries sold the property to its sixth owner, Loren V. Wells, the founder of the retail clothing chain, Bon Worth. The Wells family still owns the Castle.

Overlook’s historical significance was affirmed in 1981 when the property was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Then in 1984, the City of Asheville officially designated Overlook as a Local Historic Landmark. As a Local Historic Landmark, any alterations to the property are subject to design review by the Historic Resources Commission and the owners must receive a Certificate of Appropriateness prior to commencement of work. These historic designations help to ensure that Overlook, Fred Seely’s interpretation of Forde Abbey transposed on Sunset Mountain, remains as a visible and identifiable part of Asheville’s architectural and social history.

Photo Credits: (Note: Captions on photos by Dale Wayne Slusser)

Mountaintop aerial view of Overlook-Collection of Fred Loring Seely, III, copy donated to the Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

Fred Seely, Age 30-“Fred Seely Deserts Business to Study Law”, The Pharmaceutical Era, Volume 28, September 18, 1902 (New York, NY: D. O. Haynes & Company, 1902) page 314.

Seely Sketch for the Grove Park Inn– PN:1_E.0 -gpi0232 from the GROVE PARK INN – PHOTOGRAPH ALBUM #2: -Grove Park Inn Collection (c. 1913), D. H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville. http://toto.lib.unca.edu/findingaids/photo/grove_park_inn/jpeg_album_2/PN1E_0.jpg

1903 Map– Image – MAP 501, Buncombe County Special Collections at Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Lyndhurst– File: Lyndhurst Tarrytown NY – front facade.jpg. (2021, February 27). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Retrieved 15:02, March 19, 2021 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Lyndhurst_Tarrytown_NY_-_front_facade.jpg&oldid=536887056.

Zealandia, c. 1899 photo– Marriott Canby Morris, 1863-1948, photographer. “Mr. Brown’s house. Zealandia, on Beaucatcher Mt. Mr. Brown on porch”. [Asheville, NC], March 21, 1890. Courtesy: Library Company of Philadelphia, Print Department, Marriott C. Morris Collection [P.9895.1597].

Little Thakem photo- ‘File:Little Thakeham, an early Lutyens country-house-geograph-5301124-by-Stefan-Czapski.jpg’, Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, 23 March 2021, 05:44 UTC,- https://commons.wikimedia.org

Forde Abbey-South Front– from: Charmouth: Its Church and Its People, An illustrated history of the last Thousand Years. by Neil Mattingsly (Changing Spaces: Dorset, England).

Overlook Castle (color aerial photo)-Jerry Sternberg- http://gospeljerry.com/Article_1_Seelys_Castle_An_Asheville_Wonder.php

Forde Abbey of the Parish of Thorncomb Sketch– https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol1/pp239-249

Overlook In the County of Buncombe Sketch– by Dale Wayne Slusser.

Forde Abbey 1539 Sketch-from: Charmouth: Its Church and Its People, An illustrated history of the last Thousand Years. by Neil Mattingsly (Changing Spaces: Dorset, England).

Forde Abbey Tower/Porch– “Plate 186: Thorncombe, Forde Abbey, The Porch”, in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 1, West (London, 1952), p. 186. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol1/plate-186 [accessed 5 April 2021].

Overlook, South Front– Jerry Sternberg -http://gospeljerry.com/Article_1_Seelys_Castle_An_Asheville_Wonder.php

Overlook Reception Hall– P2015.06, Overlook 13: Overlook Castle interior, reception court [Print] Overlook Castle Photographic Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804.

Overlook Great Hall- Living Room– Collection of Fred Loring Seely, III, copy donated to the Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

Forde Abbey Abbots Hall– File: Forde Abbey Entrance Hall.jpg. (2021, January 26). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Retrieved 14:52, April 5, 2021 from – https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Forde_Abbey_Entrance_Hall.jpg&oldid=528460239.

Forde Abbey refectory– https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/31947478585336389/

Overlook Old Library/Music Room– P2015.06, Overlook 18: Overlook Castle interior, music room [Print] Overlook Castle Photographic Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804.

Overlook Library Glass Doors– Collection of Fred Loring Seely, III, copy donated to the Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

Overlook New Library– Collection of Fred Loring Seely, III, copy donated to the Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

Forde Abbey West Dining Room– “Plate 193: Thorncombe, Forde Abbey, The Saloon, Looking N.”, in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 1, West (London, 1952), p. 193. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol1/plate-193 [accessed 7 April 2021].

Overlook Stair Hall– Collection of Fred Loring Seely, III, copy donated to the Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

Overlook Library Mantle-Surround– Collection of Fred Loring Seely, III, copy donated to the Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

[1] Most of this information was gleaned from Seely’s two-page obituary: Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC. March 15, 1942, Section B, pages 1-2.

[2] “Bromo-Quinine Manufactory”, Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC, July 14, 1898, page 4.

[3] “Patents Obtained”, Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC, October 16, 1899, page 1.

[4] “Fred L. Seely Deserts Business For Law Books”, The Pharmaceutical Era, Volume 28, September18, 1902, United States: D. O. Haynes & Company, 1902, page 314.

[5] Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC. March 15, 1942, Section B, page 2.

[6] “Fred L. Seeley, Who Publishes And Edits The Atlanta Georgian”, The Montgomery Times, Montgomery, Alabama -November 1, 1907, page 1.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Hearst Gets Into the Southern Field”, The Twin-City Daily Sentinel, Winston-Salem, NC, February 5, 1912, page 8.

[9] See: Built for the Ages: A History of the Grove Park Inn, by Bruce E Johnson (Asheville, NC, 1991)

[10] See the McKibben drawings for the Grove Park Inn: # O012-XX Grove Park Inn architectural drawings – 1912, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC. For more information about McKibbin and the Southern Ferro-Concrete Company: North Carolina Architects and Builders: A Biographical Dictionary https://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000545

[11] Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC. January 17, 1913, page 3.

[12] Asheville Daily Gazette, Asheville, NC. June 19, 1900, page 4.

[13] “Dr. Grove Closes Option on Overlook”, Asheville Weekly Citizen, Asheville, NC. May 10, 1910, page 4.

[14] Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC. September 11, 1911, page 1.

[15] (Work resumed) The Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, NC, May24, 1914, page 23.; (permit issued) Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC. July 24, 1914, page 5.

[16] Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC. November 21, 1916, page 1.

[17] “Gothic Revival Architecture”, by David Ross, Editor-website: Britain Express: Passionate about British Heritage, https://www.britainexpress.com/architecture/gothic-revival.htm

[18] Ibid.

[19] https://lyndhurst.org/history/ -Lyndhurst is now owned and operated as a site of the National Trust For Historic Preservation.

[20] Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC. August 3, 1889, page 1.

[21] In the Introduction to: Arts & Crafts Houses I, (Phaidon Press Limited: London, England, 1991).

[22] From Forde Abbey website: https://www.fordeabbey.co.uk/house/

[23] Forde Abbey: The Story Behind the Stones, by Christian Tyler (Stanbridge, Wimborne Minister, Dorset, England: The Dovecote Press, 2017) page 36.

[24] Ibid.

[25] From the National Register Nomination, by Lois Staton (July 1980). “Overlook” (pdf). National Register of Historic Places – Nomination and Inventory. North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office. – https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/nr/BN0037.pdf