![]()

Preservation Grants

2023 Grant Recipients:

$5,000 for Heating System and Duct Cleaning at Church of the Incarnation

The Church of the Incarnation in Black Mountain is a one story, gothic revival church with a granite foundation and clad in wood shingles. The church was originally constructed as the St. James Episcopal Church. In 1908, four lots were purchased for $400 to build the church. Additional funds were raised, and the cornerstone of the building was laid on July 25, 1912. The church was consecrated on September 23, 1917. The St. James Episcopal Church congregation moved out of the building in 1994 into a larger church. Sixteen of the original stained glass windows in the church were moved to their new building, but several remain in the building. The current congregation moved into the building sometime before 2007. There are currently less than 30 members in the congregation.

The building needs several repairs to allow it to continue to be used by the congregation, including foundation repairs and installation of gutters to stop water from infiltrating the basement, installation of a new heating system and duct cleaning, installation of a sump pump to help remove water from the basement, and removal and repair was water damaged walls in the basement. We are excited to support this project to prevent permanent damage to the building and allow the building to stay in use.

$5,000 for HVAC system replacement at Shiloh African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church

Shiloh African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church is a historically important church. The existing heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) system in the church is 28 years old and has failed twice this year. While HVAC systems are not typically considered preservation projects, the failure of the heating system in winter could potentially lead to significant damage to the historic fabric. We are excited to support this project that will allow the building to remain open and serve its congregation and community for several years to come.

From the application: Shiloh African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church is one of the oldest A.M.E. Zion churches continually serving a predominately African American congregation in the Asheville area. The earliest reference to the church is recorded in an 1871 deed referring to the sale of one acre of land to the trustees of the church. In 1889, the congregation sold the church and church property to the agent for the Biltmore Estate for $1000. This sale allowed the congregation to move a church building and their historic cemetery to their current locations. The building that was moved served the congregation until 1928 when they erected a new brick church (the current building) on the 1889 site.

$5,000 for the replacement of the roof at Bascom Lamar Lunsford Homestead

Bascom Lamar Lunsford was a musician, folklorist, and musical festival organizer, which included the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival. Lunsford worked in many different professions over the years. As a salesman, he traveled through the mountains, where he developed his vast repertoire of traditional songs and tunes.

His historic 1938 home is located in Leicester. Its current roof is over 30 years old and is badly deteriorated and leaking. We are happy to fund this project to save this building for future generations.

From the application: It is the old homestead of Bascom Lamar Lunsford – “Minstrel of the Appalachians” and future home of The Pondering Bascom Performing Arts & Education Center. We are a grassroots nonprofit organization dedicated to the preservation, promotion and continued education in traditional Appalachian performing arts, cultural arts, regional history and sustainable lifestyle practices.

$4,100 for the research, fabrication, and installation of an interpretive history panel in the Congregation Beth HaTephila section of Riverside Cemetery

The history of Asheville’s Jewish community has long been ignored. Sharon Fahrer is working to document the history of the Jewish community and their contributions to the culture of Asheville. As part of this ongoing project, Fahrer plans to research the history of the Congregation Beth HaTephila section of Riverside Cemetery and Jewish burial rituals. This research will be turned into an interpretive history panel to share this important history with visitors to the cemetery. We are pleased about the installation of the interpretation panel.

From the application: Visitors from outside the South often are surprised there are Jewish communities in the Southeast and are especially surprised to find them in the Appalachian Mountains. Riverside Cemetery, a Victorian rural garden cemetery, offers a look at the final resting place of people who shaped Asheville. This project will expand awareness and understanding of the history of Asheville’s Jewish community. It will explain the purpose, some burial rituals, and the story of how the cemetery belonging to the Congregation Beth HaTephila (CBHT) was located within Riverside Cemetery. CBHT is the only religious institution that has a cemetery within Riverside. Recognition of the existence of a Jewish community in Asheville was long ignored.

$5,000 for gutter replacement at St. Matthias Episcopal Church

St. Matthias has been developing a comprehensive drainage and grading plan to help preserve the historic church building. As they move forward with planning a larger, comprehensive project, installing new gutters and downspouts on the building will help stop water intrusion. We are excited to continue to support this phase of their project and are thrilled about their continued efforts to save this significant historic landmark.

From the application: St. Matthias was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. It is believed to be the oldest Black congregation in Asheville, established initially as a Freedman’s Church in 1867. It was the location of the first school for Blacks in Asheville, beginning in 1872, and as far as we know was the only school for Blacks in the city until the first public school opened in 1885. The current church was built in 1892-94 by formerly enslaved master brick mason and congregant James Vester Miller, who went on to build the Asheville Municipal Building and other prominent public structures in the city. His descendants are active in the church today.

$5,000 for installing a new entrance gate at Violet Hill Cemetery

Violet Hill Cemetery is significantly important as the primary burial place for African Americans, beginning in 1932 because of segregation. Last year, the existing gate at the main entrance broke, which caused the cemetery to suffer the theft of maintenance equipment. We are happy to fund a new, lockable gate, which will prevent further vandalism and allow for this historic site’s continued maintenance and protection.

From the application: Violet Hill Cemetery was established by Dr. L.O. Miller in 1932 to provide the underserved Black community with an affordable, decent facility to bury their loved ones during segregation, when options were limited. At the time, Riverside Cemetery had only a very small section reserved for Black burials, and the South Asheville Cemetery was filling up, so Violet Hill filled an important need.

Today Violet Hill Cemetery holds over 5,000 graves that include a “Who’s Who” of individuals who contributed to the betterment of our Black and Brown communities. Some are recognized as the first Blacks to hold positions of significance in their respective professions or career. Our graves include such notables as James Vester Miller, E.W. Pearson, Clifford Cotton, Dr Lee (of Stephens Lee High School), Mr. and Mrs. McQueen, Ernest Willis Gatewood (a pro basketball player), and many other community activists and Black leaders.

$5,000 for the maintenance, repair, and upgrade of the Biltmore Industries Homespun Museum

Biltmore Industries is important to the history of Asheville, and its Homespun Museum is a gem. The museum is in need of basic maintenance, which includes interior painting, electrical upgrades, and installation of climate control systems. These projects will allow the museum to (1) improve the conservation and preservation of its collection; (2) improve visitor experience and education; (3) improve accessibility and safety for visitors; and (4) increase visibility to create more revenue for the museum. We are excited to be a part of helping preserve this historically significant place.

From the application: Biltmore Industries was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. We are historically connected to The Cathedral of All Souls, the Biltmore Estate and the Grove Park Inn. These are important connections that we do our best to maintain and educate visitors about. Beyond that, we represent a span of textile history that encompasses 18th and 19th century technology that was still in use in the 20th century. Because Biltmore Industries utilized ancient and modern techniques and was in operation from early 1900 to early 1980, there is so much history wrapped up in the inner workings. From dye chemical technology improvements, workplace law and safety changes, continuing production during the two World Wars, and converting from steam power to DC and then AC power – our museum is a treasure trove of information.

$5000 for gutter replacement at St. Matthias Episcopal Church

St. Matthias has been working to develop a comprehensive drainage and grading project which is needed to preserve the church buildings. We are excited to support this phase of their extremely well-researched and strategized stabilization of this significant historic landmark.

$5,000 to thoroughly update, rebuild, and refresh the Basilica Preservation Fund website

This contribution is relatively modest in light of the much larger fundraising effort happening to preserve this important landmark, however, we hope that it will be instrumental in facilitating their much larger goal. We are pleased to support the Basilica Preservation Fund in this way!

$5000 for plaster repair and painting of water-damaged walls at Berry Temple Church

Berry Temple is now home to the City as Classroom: The Berry Temple Community and STEAM Academy. The sanctuary is now used as a community auditorium and also hosts My Daddy Taught Me That students. PSABC is happy to support this adaptive reuse of an important historic church.

2022 Grant Recipients:

$5000 to Hopkins Chapel A.M.E. Zion Church

This funding is for a National Register of Historic Places nomination and a building assessment. In addition to being built by noted brick mason, James Vester Miller, and designed by architect Richard Sharp Smith, this church has an incredible history which you can read at hopkinschapelamezion.org.

$1500 matching grant to the Norwood Park Neighborhood Association

The Norwood Park neighborhood is home to one of our City’s secret sidewalks. The 100 plus year old walkway spans more than 300 feet connecting the residents of Norwood Park to the goods and services of Merrimon Avenue. This grant will fund the research and documentation of the history of this walkway in hopes of ensuring its preservation in the neighborhood for another 100 years.

$2500 for Asheville: A Graphic Novel History

Author Matthew K. Manning and artist Jarrett Rutland are creating this 100-page graphic novel retelling of Asheville’s storied history in hopes that it will resonate not just with longtime fans of our city, but also with a younger audience. The story will lead the reader through history from prehistoric times to today, letting them see the city form first-hand.

$4000 to the Stumptown Neighborhood Association

This grant will fund video interviews for story gathering and sharing in order to celebrate, honor and preserve the rich history of this neighborhood.

From the application: Stumptown was a vibrant, closely knit Black neighborhood located “in the hollow under the brow of the hill” between what is now Riverside Cemetery, Pearson Drive, and Courtland Avenue. It had active churches, stores, and community cohesion. Black residents today still call their neighborhood Stumptown, though urban renewal and gentrification have thoroughly eroded what was a once a thriving Black community.

Research shows that Stumptown is older than the adjacent Montford neighborhood – it developed around a piece of property on Pearson Drive given to Tempie Avery by her former enslaver Nicholas Woodfin in 1868. As Black history is not as present in written historical records, we do not have an exact date of the establishment of Stumptown, though most accounts place its inception around 1880.

The Stumptown neighborhood was redlined in the late 1930s, but remained a strong community through the 1960s, despite systemic neglect which made the area vulnerable to displacement. The majority of homes and lots in the neighborhood were taken by the City of Asheville during urban renewal in the 1970s for the Montford Recreation Complex. With the naming of the complex after Montford and the subsequent gentrification of the area, the story of Stumptown has been mostly hidden.

There has been some documentation of stories from Stumptown residents, but it is not easily accessible to the general public. While the early history of the neighborhood was acknowledged by the renaming of the community center to the Tempie Avery Center, there is no signage acknowledging the existence of the Stumptown neighborhood or the contributions of its residents.

The Stumptown Neighborhood Association wants to address this erasure and build awareness of this history and culture through story gathering/sharing and signage.

$2000 to Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center

This grant is for the installation of protective barriers to protect the recently completed conservation of two frescos painted in the summer of 1944 by luminary of the Mexican Mural Renaissance, Jean Charlot.

$5000 to La Esperanza Real Estate Cooperative

This funding will support the extensive repairs and upgrades needed at 528 Emma Road.

From the application: The La Esperanza (“The Hope” in English) building, which was built in 1914, is located in the center of the Emma community. According to Andrea Clarke via her family oral histories, it was constructed by the renowned Black mason James Vester Miller and his crew.

La Esperanza is cooperatively owned by over 30 families in the community, many of whom also invested significant time and labor to fix up the building after it was purchased. Thanks to PODER Emma’s community development efforts which made this possible, these community members, including Latinx immigrants, who might not otherwise have access to owning real estate are able to build community wealth through La Esperanza.

The building houses Colaborativa La Milpa, a collective of Latinx-led grassroots groups working to uplift and protect the community. The members of the collective are Compañeros Inmigrantes de las Montañas en Acción (CIMA), Raíces Emma – Erwin, PODER Emma, and Ma hñäkihu: Indigenous Language Preservation Project.

La Esperanza also houses worker-owned cooperatives Power in Number Bookkeeping, Cenzontle Language Justice Cooperative, Quetzal Community Real Estate, and Chispas.

Serving as a community hub, community members visit La Esperanza to access supportive services provided by La Milpa’s organizations and the co-ops. A large community room on the first floor of La Esperanza is used for youth programs, classes, meetings, and events.

$5000 awarded to Douglas Ellington House

On the personal estate of the renowned architect, Douglas Ellington, this grant will fund repairs to the historic tool shed. The tool shed was built with logs and stones from the estate. Without this necessary interference, the tool shed is in danger of complete collapse.

$2500 awarded to “We Built This: Profiles of Black Architects and Builders in North Carolina”

This exhibit was put together by Preservation North Carolina, bringing much needed attention to the legacy of Black craftsmen throughout the state. The PSABC grant helps fund the rental fee and transportation costs to host the exhibit in our community. One local builder included in the exhibit is James Vester Miller who was involved with many projects throughout his lifetime, including the YMI (pictured below).

2021 Grant Recipients:

$2000 awarded to Black Mountain College Museum + Art Center for phase two of a project to restore and protect frescoes in the Studies Building. For more information on the fresco restoration that won a 2021 Griffin Award, visit our website at PSABC.org.

From the application:

In fall 2020, BMCM+AC completed a project to mediate damage, repair, and conserve two frescoes, Inspiration and Knowledge, painted by luminary of the Mexican Mural Renaissance Jean Charlot along with Black Mountain College students in the summer of 1944. These evocative, site-specific pieces, created in the true fresco style, had suffered from fading, molding, and surface damage from graffiti and repeated cleaning over the past 77 years.

Following conservation efforts, these landmarks can now be appreciated and enjoyed by generations to come as the last remaining artworks at the historic, former Black Mountain College campus.

Our next phase, for which we are now seeking funding, will be the installation of protective barriers to prevent further degradation of the murals, and educational efforts including signage to explain to Rockmont campers, property owners and stakeholders, LEAF festival goers, BMC enthusiasts and other visitors to the site the historical and cultural significance of the murals.

$2500 awarded to the Railroad and Incarcerated Laborers (RAIL) Memorial Project for educational signage at Swannanoa gap in the Ridgecrest. Check out the website therailproject.org for more information on this project.

From the application:

The RAIL Memorial Project seeks to find tangible ways to honor and memorialize the incredible work and tragic sacrifice of over 3,000 incarcerated laborers, over 90% of whom were African American, who built the railroad up the mountain from Old Fort to Swannanoa in the late 1870s.

The Mountain Division of the Western NC Railroad was constructed between 1875 and 1879. The work was brutal and the conditions were severe. Over 95% of the labor was provided by prisoners–about 3,000 men and a few hundred women. Most were African American. They were shipped in boxcars from the Raleigh penitentiary to the end of the rail line at Henry Station (where Mill Creek Road joins Old US Hwy 70). History tells us that the prisoners–many who had formerly been enslaved–were, more often than not, wrongly convicted on inadequate or false evidence. Their sentences were for terms much longer than those imposed on white people. For these incarcerated railroad laborers, prison was an extension of slavery.

The Mountain Division ran from Henry Station to the western end of the Swannanoa Tunnel at Ridgecrest. By straight line, these points are 3.4 miles apart, but the prisoners cleared and smoothed the path and laid 9.4 miles of rails, as many curves and loops were required to climb 1,002 feet in elevation. Seven tunnels were pounded through solid rock, with bare muscle aided by black powder and some nitroglycerine. Many convicts died. The track became a graveyard.

An exact count of deaths was never kept, but at least 139 people perished. The death toll may be closer to 300. When a prisoner died, another would be brought from Raleigh.

Currently, there is little written in public spaces about the tremendous and unwilling sacrifice made by these incarcerated workers to connect the railroad to Asheville.

$2500 awarded to the Kenilworth Residents Association (KRA) for educational signage recognizing George Gibson and his family’s contribution to the neighborhood and the South Asheville Cemetery.

From the application:

Several years ago, the KRA, in concert with representatives from the African American community that has long been a vital part of Kenilworth, embarked on a quest to re-name a creek that runs through the neighborhood after Louise Gibson, a beloved longtime resident. The community was able to have the creek officially re-named Gibson Creek and then celebrated the naming at St. John A Church here in Kenilworth that stands adjacent to the cemetery where nearly two thousand African Americans are buried, dating to slavery times. A handcrafted wooden marker indicating this name change was created and placed on private property by the creek, but the plan has always been to install large interpretive signage that would document the history of George Gibson and his family and the neighborhood in which they have long resided.

$5000 awarded to Shannon Rose for installation of a French Drain at her c.1930 West Asheville house as a first step in addressing water intrusion concerns.

$3000 to Priscilla Robinson for her continued work to document and tell the stories of Urban Renewal in the Southside neighborhood of Asheville.

“Life, community, and home as many Asheville Black community members once knew it is no longer present. This project will allow one to see through our eyes, walk in our shoes, and hear diverse voices speak our truth in hope of others receiving an understanding of why many are compelled to preserve the history of Asheville’s Black community.” – Priscilla Robinson

This project will focus on 3 main areas: Walton Street Park and Pool, Urban Renewal (acquisition of Urban Renewal property and reparations) and the Livingston Street School

Livingston Street School – Photo courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections

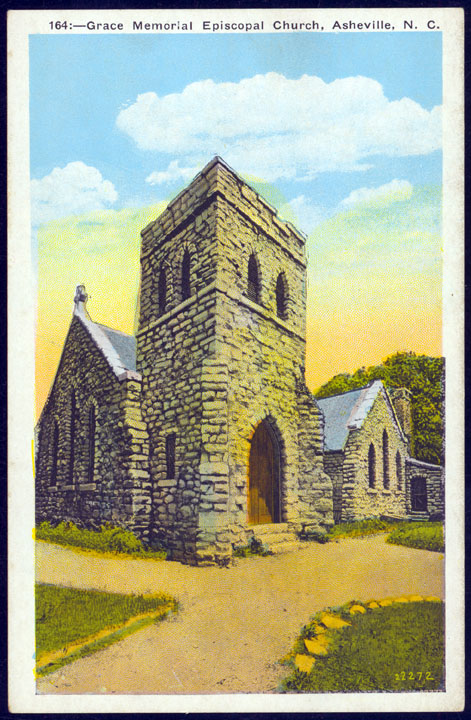

$4000 to Grace Memorial Episcopal Church towards roof replacement and parapet repairs.

Designed by Richard Sharp Smith, the supervising architect for the Biltmore House, Grace Memorial Episcopal Church has been in service since 1905 and stands as an excellent example of Gothic architecture. This grant will help reach a goal of approximately $350,000 in rehabilitation costs.

Of the church, Dale Slusser writes, “My favorite (of Smith’s churches) is the charming stone of Grace Episcopal Church on N. Merrimon Avenue. Smith’s British heritage shows in his design for Grace Church. With its cross-transept plan and small castellated tower entrance, it would feel just as comfortable sitting in any small rural village in England.”

Photo courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections

$5000 to the St. James AME Church towards roof replacement.

Parishioners are currently unable to worship at the church due to deterioration of the facility, caused in part by water intrusion. This grant will help reach a goal of $48,000 to replace the roof and is part of a large $570,000 fundraising goal to complete a larger rehabilitation effort.

Notably, St. James AME Church is one of a number of important Asheville structures credited to James Vester Miller, a prominent Black contractor in Western North Carolina.

From the application:

“During the 1960s and 1970s the East Riverside Community, which includes the East End Valley Street neighborhood, was selected as the site for one the Southeast’s largest urban renewal projects. The federal government’s urban renewal project, which was led by the East End Valley Street Community Improvement Committee, focused on relocating a significant number of businesses and residents from the area to make way for redevelopment of single family homes and apartments. The East End Valley Street neighborhood had been a traditionally historic African American neighborhood with African American owned businesses.

In addition to the neighborhood residents enduring the impacts of urban renewal, the East End Valley Street neighborhood experienced further devastation due to the development of the Interstate expansion of highway 240, which included the creation of a road through Beaucatcher Mountain. The development of the road required the removal of “300 million cubic yards of crushed granite,” months of explosive detonations, and thousands of trucks traveling in and around the East End Valley Street neighborhood for years.

One of the institutions that remained intact during those periods of extreme change and transition was the St. James AME Church. The church became a beacon of hope for the community. The community sought solace at the St. James AME Church. The church hosted community meetings and events.”

Photo courtesy of St. James AME Church

$550 for owners of the Gatehouse for consulting services.

Built in early 1898 by the Raoul family, the Gatehouse, known then as the Lodge, is the oldest structure in Albemarle Park. In need of numerous repairs, this grant will support efforts to establish this as an historic tax credit rehabilitation project. Utilizing tax credits available through the State Historic Preservation Office can be an important tool in rehabilitation projects.

Photo courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections

2020 Grant Recipients:

Thomas Chapel A.M.E. Zion Church, Black Mountain – $1800 for grading and site work for erosion control

From the application:

Centered in the heart of one of two known areas of town that have historically been associated with the African American population in Black Mountain, this church served for many years as the literal heart of the community. This building, the third Thomas Chapel building likely located on this same site, was built in 1922, following the original log church built by freed slaves, and a second church which was built sometime between 1892 and 1922. The original Thomas Chapel A.M.E. Zion Church was the first church built for the African American community in Black Mountain, serving as the mother church for later A.M.E. Zion churches and other denominations that were built in later years. This church building continues this legacy, where, from 1922 until 1974, when a new church sanctuary was built on another lot nearby, the chapel served not only as a place of spiritual importance but as a place where families gathered for social events, weddings, singing conventions, funerals, and picnics since there were no other gathering places available for the black community. Through its time as the focus of the community, the church hosted many speakers of all races, and in 1927 was selected as the host church for the A.M.E. Zion denomination’s annual church conference, hosting twenty-four churches in the Blue Ridge District. Small in size, but gigantic in its rich history, Thomas Chapel A.M.E. Zion Church is a property that only gains in significance in these times of change and movement towards continued racial equity.

River Front Development Group’s STEAM Academy – $5000 for equipment and staffing

From the application:

The STEAM Academy’s Portable Digital Photography Lab will be an opportunity for students, interns and residents to explore the people, places and events that should be recognized in the Stephens-Lee African American Heritage Museum. Participants will be tasked with creating digital and story-board presentations of the past and current community assets. By combining photography, research and art the goal is for students and adults to gain an understanding of the importance and need for preserving historic assets. Themes will include business and commerce, religious life, education, sports and social life in the community.

James Vester Miller Historic Trail – $1500 for website development

From the application:

James Vester Miller, an African American master brickmason and entrepreneur, built many of Asheville’s most remarkable buildings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as well as numerous homes in the Emma community and elsewhere in the Asheville area. The James Vester Miller Historic Trail will be a tour commemorating his work. It will include nine buildings and will reference others beyond the easily accessible walking radius of the trail.

The James Vester Miller Historic Trail and its related projects will educate natives and tourists alike about the important role that one African American Asheville native played in creating Asheville’s architectural footprint. James Vester Miller’s personal story reflects in microcosm the story of relations between the races in Asheville from the late 19th century through the early 20th century. Moreover, the relative lack of public recognition of his role in creating these remarkable historic buildings typifies white Asheville’s general failure to acknowledge the role of the African American community and of specific African American leaders in building what Asheville is today.

Western North Carolina Historical Association – $5000 for traveling and virtual exhibit

From the application:

The not-yet-titled exhibition will focus primarily on the South Asheville Cemetery, a historically African-American cemetery in Asheville, which was founded on land owned by the Smith family in the early 1800s as a burial ground for people they enslaved. The cemetery property was eventually deeded by Sarah Smith McDowell and her husband to representatives of the cemetery. It is now maintained by the South Asheville Cemetery Association, who are partners on this project.

While research for the exhibition will seek to uncover individual stories of people who are (or may be – there are only 93 headstones for nearly 2,000 graves and scant burial records) buried in the South Asheville Cemetery, the overall purpose of the exhibition will be focused on African-American burial grounds in the larger Asheville area and how county, state, and federal policies have passively and activity contributed to the deterioration of these sacred places in a way that has not equally impacted the final resting places of whites. The exhibition will be designed around primary documentation and the voices and input of African American community partners, particularly those with a family connection to the cemetery.

Well into the 1950s nearly all American cemeteries had some version of racial restrictions. Clarence B. Jones, in an op-ed for the Washington Post, wrote, “The neglect of historic African American cemeteries is as widespread as it is unknown. Throughout the 19th century and much of the 20th, African Americans were segregated even in death, often buried in off-the-beaten-path Black cemeteries that, over the years, received little funding and fell into disrepair.”

Examples from the South Asheville Cemetery will illustrate how systemic racism has caused such neglect, disrepair, and – even – desecration of Black cemeteries resulting in the loss of African American history and culture.

For instance, George Avery, a blacksmith who had once been enslaved by the McDowell family, became caretaker of the cemetery after emancipation. Historians often lament that Avery tracked the burials by memory and did not leave written records, so – when he passed away in 1938 – much of the knowledge of who was buried in the cemetery – and where they were buried – was lost.

There is much more to the story, however, than Avery not leaving written records. Avery was enslaved until he was almost 20 years old. He was not allowed to attend school. North Carolina law prohibited teaching enslaved people to read or write. So, by digging deeper, and understanding more of the history of systemic racism, we can better answer the question – “Why don’t we know who is buried at the South Asheville Cemetery?” with more than the surface answer of “Well, George Avery didn’t leave any written records.”

We can begin to understand why he might not have left written records by looking at written records. Documents available through the Buncombe County Register of Deeds show that Avery signed his name with an “X” throughout his life. It then becomes likely that there are no written records because laws written by white officials did not allow enslaved people to learn to read or write – and shows that black families are still feeling the repercussions of laws written and abolished over 150 years ago.

Likely, however, there is even more to the story. Placing grave markers would have been the responsibility of the family. Many families, however, could not afford markers – and based on oral history – many could not even afford the $1 fee due to the McDowell family to dig the grave. Graves were then marked with wooden crosses, field stones, or topography that constantly changed and did not indicate the name of the deceased. Understanding why graves were left unmarked means understanding why an African American family might not have the money to place a grave marker.

It also means, however, better understanding African American funerary traditions and how and why they originated. In a 2016 article in The Atlantic, Tiffany Stanley wrote, “Particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, if slaves were allowed to bury their own dead and craft their own rituals, away from the overseeing eyes of whites, they could plan for their freedom, spiritually and physically.”

The South Asheville Cemetery was closed to new burials in 1943 because the City of Asheville annexed the area and burials were not allowed in the city limits. (More research is needed to better understand the motivations behind this annexation; however, at some point the cemetery was the location of a proposed condominium project.) As time passed and the cemetery became overgrown, aging descendants could no longer navigate the terrain and many of the graves were forgotten. We hope that with this exhibition we can help remember some of those interred within the cemetery and increase community participation in its continued upkeep.

The exhibition will also seek to document stories from other African-American burial grounds in Asheville and Buncombe County, including (segregated) Riverside Cemetery, various church and family cemeteries, and the unmarked graves of incarcerated railroad laborers, who were buried near the tracks and tunnels they died constructing.

Shiloh African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and Cemetery – $4600 for a National Register of Historic Places nomination

From the application:

Shiloh African Methodist Episcopal Zion church has been in existence since 1874 and there is evidence that it was active as early as 1871. Shiloh was an African American settlement populated after the Civil War by African American freedmen on a small parcel near what is now known as the Cedarcliff Gate on the Biltmore Estate. That former community is referred to as “Old Shilo”.

The church was most likely built of logs. Church history states that the founders raised $7.00 to purchase the original lot and establish the church. In 1888 when George Vanderbilt’s agent Charles McNamee was buying the land for the estate he approached Rev. William Logan, a member of the Shiloh community. Mr. McNamee offered the congregation of the Shiloh AME Zion Church $1000 to move their congregation, church and cemetery across the Asheville- Buncombe Highway to a two acre lot. Unfortunately, the original Shiloh AME Zion Church burned to the ground before it could be moved. The congregation obtained an unused Presbyterian Church for the move. The graves were dug up and re-interred at the new location and New Shiloh was born.

After the move, the church was used not only as a place of worship but also as a community center and as a school for the children of Shiloh. Laborers on the Biltmore Estate whose children went to the school were encouraged to set aside a portion of their salary to help pay for a teacher.

In 1923 the Trustees of the Shiloh AME Zion Church took on a mortgage to build a new church. By 1928 the church was built and the debt was paid. This is the church that exists today.

Western North Carolina Historical Association – $4150 to research, design, print and install a new permanent exhibit in the Smith-McDowell House.

Photo credit: NC Room, Pack Memorial Library

Photo credit: NC Room, Pack Memorial Library

From the application:

Our new permanent exhibit will seek to present a more balanced and holistic picture of what life was like pre- and post-Civil War for all people who resided on the property. Staff will design new interpretive panels that will take visitors on a journey through time beginning with early white settlement and removal of native populations, which will be viewed prior to entering any of the period rooms.

The tour will then continue into the basement of the house – home to the winter kitchen. Here, visitors will view one interpretive panel which gives a broad overview of slavery in the mountains before entering the kitchen and “meeting” a woman – Tilda – who, along with her husband and children, was enslaved by the Smith family.

The tour will continue to the second floor, where visitors will encounter other residents of the home – including James McConnell and Polly Patton Smith, Sarah Smith McDowell (the daughter of James and Polly, who owned the house in the 1860s and 1870s), William Wallace McDowell (Sarah’s husband), George Avery (enslaved by the McDowells), and Mary Francis Garratt (an immigrant, whose father purchased the house to bring his daughter, who was suffering from TB, to the mountains).

High Top Colony Neighborhood Association – $2800 for a National Register of Historic Places nomination

From the application:

High Top Colony in Black Mountain, North Carolina was founded in 1919 by Roy John, a secretary with the YMCA, and associated with the neighboring Blue Ridge Assembly of the YMCA (founded in 1912 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979), the district includes a grouping of primarily 1919 to early 1920s Rustic Revival cottages. The cottages were built for use as summer homes for those attending conferences at the Blue Ridge Assembly, but through the years have become a mixture of year-round residences and summer cottages.

A few of the cottages were built after this initial development time, from 1939 – 1940, in the Bungalow style, and there are also a few modern additions into the neighborhood of cottages built in the 1960s and 1970s, with one as late as the 1990s. The district is significant for its association with the YMCA and the Blue Ridge Assembly, because of the importance of the religious retreat movement within the mountains of western North Carolina in the early part of the twentieth century and for the architectural significance of the Rustic Revival and Bungalow styles of the cottages. Additionally, further research of the association of Dr. Willis Duke Weatherford, founder of the Blue Ridge Assembly, and his connection to the High Top Colony will be important pieces of history to be included in the nomination.

2019 Grant Recipients:

Hood Huggers International – New Bus

Hood Tours offer bus tours of Asheville’s African American neighborhoods and landmarks. The mix of the history and community with place is the perfect fit for our grant program. In their words, “Hood Tours tells the long-overlooked stories of African Americans in Asheville. We showcase history, art, greenspaces, and current-day grassroots initiatives. We’ve given tours to numerous school groups, university students, and church groups.”

PSABC is pleased to fund $5000 towards the purchase of a new bus for Hood Huggers International which will allow them to offer more tours.

SoundSpace LLC – Rabbit’s Motel

Built in 1948, Rabbit’s Tourist Court was a premier African American motel of its time. After sitting vacant for more than a decade, the family who owned Rabbit’s for five generations was all that stood between this iconic place and almost certain demolition. Multiple offers to purchase the property were ignored before Claude Coleman Jr. and Brett Spivey shared their vision for a music rehearsal space, soul food kitchen and cultural landmark called SoundSpace @ Rabbit’s.

As Coleman points out, “Rabbit’s Tourist Court has been a part of the African-American community for more than 60 years. It is intrinsically connected to the story of Asheville. These connections must not only be preserved, but recreated and strengthened.”

PSABC is excited to contribute $5000 in funding towards Phase 1 of this project. These funds will be put towards efforts to stabilize and water proof the foundation at Rabbit’s.

Montford Neighborhood Association – Bus shelter and history panel

Last May one of two newly installed Montford bus shelters with history panels was destroyed by a suspected drunk driver. The driver was never caught and it was left to the neighborhood association to figure out how to pay for a new installation.

When PSABC received the grant application in early 2019, we were inspired by the dedication shown by the individuals and businesses in Montford who had worked to raise nearly all of the funds needed to replace the bus shelter. The damaged history panel told the story of “Lost” Montford homes and Montford’s African American community – making it the perfect fit for an education preservation grant. PSABC is honored to fund the $2000 funding gap for this bus shelter to the Montford Neighborhood Association.

Swannanoa Valley Museum & History Center – Pathways from the Past permanent exhibit

Founded in 1989, the Swannanoa Valley Museum & History Center is the primary museum of general, local history in Buncombe County. PSABC is proud to provide $1000 of funding towards new exhibit panels for their permanent exhibition, Pathways from the Past, which highlights the settlement and development of eastern Buncombe County. Their efforts to make the project inclusive was important to our decision to fund this project. Executive Director Anne Chesky Smith explains, “Text from the panels will seek to equitably represent the stories of all those who have shaped the Swannanoa Valley, not just those whose voices tend to be loudest in our history.”

Calvary Presbyterian Church – $5000

Calvary Presbyterian Church was founded in 1891 and originally located on Eagle Street. Founder, Dr. Charles Bradford Dusenbury, was also a founder of the Young Men’s Institute (YMI) and he and his wife, Mrs. Lula Dusenbury, started a school in the basement of the church that served African American children and adults.

In 1926 the church moved to its current location in the heart of the East End neighborhood. Still active today, the church has an open and diverse congregation and offers a wide range of services to the community.

This grant will help the church meet funding needs to upgrade the plumbing.

In this age of rampant gentrification – irreplaceable loss of truths, loss of community, history and heritage, loss of life-giving culture, it is imperative that Calvary, and other churches and institutions begun by African Americans continue to stand and thrive. -Pastor, Rev. Patricia Bacon

South Asheville Cemetery Association – $5000

The South Asheville Cemetery began as a burial ground for enslaved people and is the oldest public cemetery for African Americans in Western North Carolina. The first known caretaker was a man named George Avery. Enslaved, Mr. Avery was owned by William Wallace McDowell, of the Smith-McDowell house, who entrusted him as the manager of the cemetery located on the family property.

Though it is thought to be the final resting place for 2000 African Americans, there are only 93 headstones with name and date information. Other graves were marked with field stones or handmade crosses making proper care of the grounds extremely important.

Led by members of the St. John A Baptist Church community, volunteers have worked for decades to maintain the cemetery, but overgrown vegetation is not the only threat. Tucked away in the neighborhood of Kenilworth, this two acre plot is threatened by development on all sides.

This grant will allow for the South Asheville Cemetery Association to complete a nomination for the National Register of Historic Places. Receiving this recognition will be instrumental in building public awareness of the cemetery and will be leveraged to seek additional funding to preserve, restore and enhance the cemetery and education efforts associated with it.