-Dale Wayne Slusser -November 2023

“No prettier or more accessible location for the erection of handsome houses exists in the city than that of Prospect Park,”[1] announced the May 28, 1889, edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times. Prospect Park, Cliveden Park, Park Square, and Factory Hill, were nineteenth century developments that today are singularly known as the West End/Clingman neighborhood. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, before the land west of the French Broad River was developed into “West Asheville,” these four neighborhoods and what is now the “River Arts District” (along the east bank of the French Broad River) was commonly referred to as “West Asheville” or the “West End”. Like many of Asheville’s historic neighborhoods, the “West End” flourished during the late nineteenth century and early to mid-twentieth century, but then declined into peril and neglect on into the twenty-first century. Although much of the original neighborhood is long gone, today the “West End” is experiencing a resurgence and redevelopment.

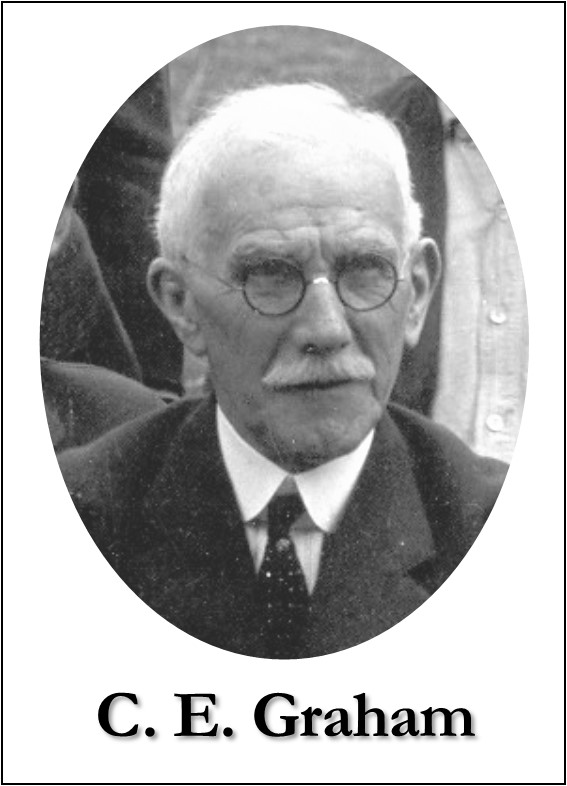

The story of Prospect Park cannot be told without first telling the story of C. E. Graham and his establishment of the Asheville Cotton Mills in 1887. Charles Edgar Graham, was born in Newton, NC on November 16, 1854. He began his business career in the mercantile business in Hickory, NC, moving from there to Asheville in 1879, at the age of 25. Already a consummate businessman, immediately upon moving to Asheville, Graham erected a three-story brick store “at the corner of Court Square and N. Main Street”. [2] In 1881, Graham solicited business partner, Henry Redwood, to invest in his business, establishing “Graham & Redwood”, with Redwood acting as the store manager. By 1884, “C. E. Graham & Company”, consisting of C. E. Graham and his younger brother R. L. (Robert Lee) Graham, had been established, and in 1885, in addition to his wholesale business, Graham began a shoe factory in Asheville.[3]

Even more that a good businessman, Graham was an adroit capitalist, with an ability to solicit investors and form partnerships to establish new companies and “enterprises”. In addition to being one of the directors of the First National Bank, in 1886, C. E. Graham established the “French Broad Bank”, with Graham serving as President, William E. Breese as Secretary and Joseph S. Adams (father of later Judge Junius Adams) serving as solicitor.[4] The new bank was established mostly for working class citizens, and boldly advertised that “The Savings of Mechanics and Laboring Men Particularly Solicited”.[5]

In 1887, Graham officially “retired” from the firm of C. E. Graham & Company, passing along the business to his brother, R. L. Graham and partners J. F. Graves, and J. Y. Jordan.[6] At that time Graham also sold his interest in the “Huguenot Mills” in Greenville, SC, which he had purchased in in 1886,[7] and sold the Huguenot Mills to its manager, F. H. Fulenwider.[8] Upon Graham’s “retirement” it was announced that he was retiring from the firm of C. E. Graham & Company, “in order to engage in a different and enlarged field of enterprise”.[9] It was soon announced that Graham’s new “enlarged field of enterprise” was the establishment of a “cotton factory” (more correctly-a textile mill) to manufacture cotton textiles.[10] “All the necessary steps are being taken looking to the establishment of a cotton factory here the coming spring.”,[11] announced the January 14, 1887 edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times. Just two years before the development of Prospect Park was announced, C. E. Graham, began building a “cotton factory” on the west side of Roberts Street, adjacent to the land that would soon be developed into Prospect Park.

In April of 1887, the foundations of the cotton factory were being laid, by sub-contractors, “Messrs Murdoch and Colvin”,[12] and “seven carloads of machinery” had arrived for the new factory. Graham temporarily set up some of the new machinery in leased facilities near the construction site. The new factory, which was being constructed under the supervision of general contractor E. J. Aston, it was reported, would be two-stories high and “55 by 270 feet”, and would have “4,040 spindles” on “250 plaid looms”.[13] By 1888, with an addition to the factory, supported by new investors E. H. Fulenwiler, of Greenville, SC and M. H. Cone of Baltimore, MD, the factory grew to be 445 feet long with 6,300 spindles on over 260 looms.[14]

Mr. Graham’s massive cotton factory was not the only manufacturing enterprise being built in Asheville in the late 1880’s. In fact, just as the cotton factory was nearing completion in June of 1887, the Asheville Citizen-Times reported that “The old depot section of our city is very rapidly forcing to the front as a centre of manufacturing, a mammoth cotton factory, ice factory, and planing and wood-working establishment to be erected at once”.[15] Of, course all these emerging industries would require a large workforce to operate, and affordable housing would be required nearby the factories for the workers. Mr. Graham built several cottages and tenement houses on the flat land surrounding his cotton factory on the west and the south, for some of his workers, but more housing was rapidly being needed to meet the rising demand. To meet this need, or at least to capitalize on the need, Graham also got involved in real estate development of the lands on the slopes just above (east of) the cotton factory, first with “Gwyn & West” in the development of “Prospect Park”, and then with the development of “Cliveden Park”, adjacent to “Prospect Park” to the north. “Cliveden Park,” would later turn into “Factory Hill” or “Chicken Hill”.

“Gwyn & West,” were business partners, W. B. (Walter Ballard) Gwyn and W. W. (William Whitehead) West. Gwyn, a native of Wilkes County, NC, had moved to Asheville in 1877 shortly upon receiving his license to practice law.[16] Upon opening his law practice, Gwyn advertised that he specialized in “the collection of claims”.[17] But by the 1880’s Gwyn changed his practice to specializing in real estate- selling, buying, and developing. His partner in “Gwyn & West”, W. W. West, was a native of Georgia who had moved to Asheville in 1883.[18] It appears that when it came to developing, Gywn did most of the purchasing of land, as W. W. West has few recorded property transactions in Buncombe County.

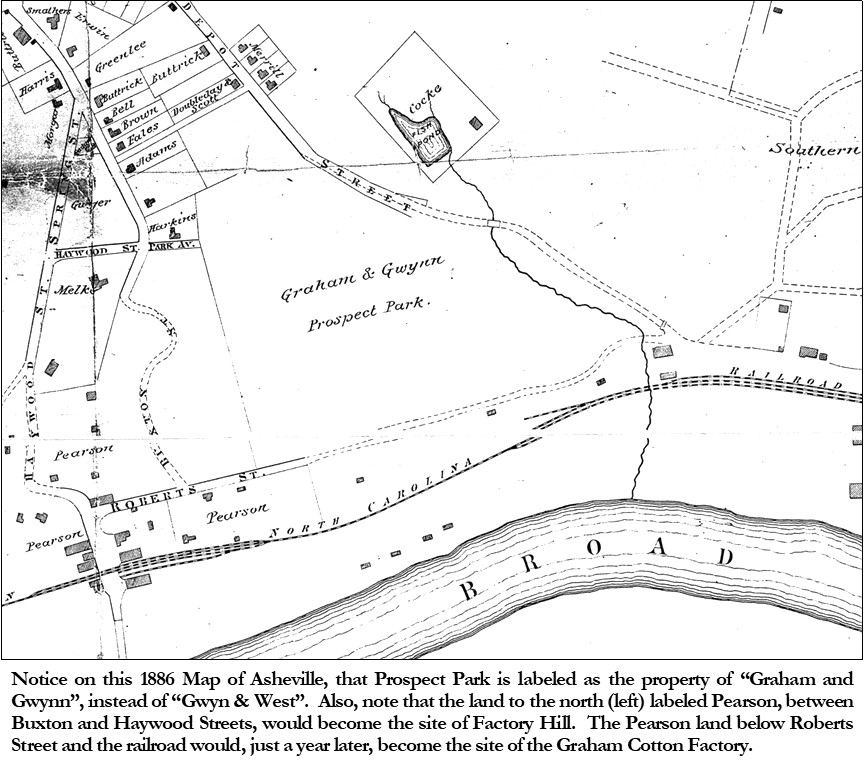

Although it’s not totally clear, at the start what was the relationship between the development of Prospect Park and the building of C. E. Graham’s cotton factory, it appears to have NOT been a “coincidence”. In April of 1884, W. B. Gwyn and C. E. Graham were the highest bidders at a courthouse sale of the lands of the estate of the late Jesse Montreville Lafayette Burnett.[19] J. M. L. Burnett was born in 1829 in Buncombe County, the son of Swan Pritchett Burnett and his wife Frances Bell Burnett, but as a young man, his father moved the family to Cocke County, TN. J. M. L. Burnett’s father Swan Pritchett Burnett, not only had owned much of the land at the mouth of the Swannanoa and French Broad Rivers in the early days, but he also came from the same branch of the Burnetts who had settled on the North Fork of the Swannanoa River. Although the land that Gwyn and Graham purchased in 1884, may have originally been part of Swan Pritchett Burnett’s lands in Buncombe County, the land had been purchased by J. M. L. Burnett in 1866 from the estate of James W. Patton.[20] Just as a side note-one cannot talk about J. M. L. Burnett without noting that his nephew, Swan Moses Burnett was the husband (before they divorced) of noted authoress, Frances Hodgson Burnett! The 110-acre J. M. L. Burnett property that Gwyn and Graham purchased would not only become the sites of the Graham cotton factory and Prospect Park, but Gwyn and Graham also resold 35 acres of it to the Asheville Cemetery Association in 1885,[21] to become the Riverside Cemetery. This would explain why, on an 1886 map of Asheville, the area that would become Prospect Park, was labeled “Graham & Gwynn”, rather than “Gwyn & West”.

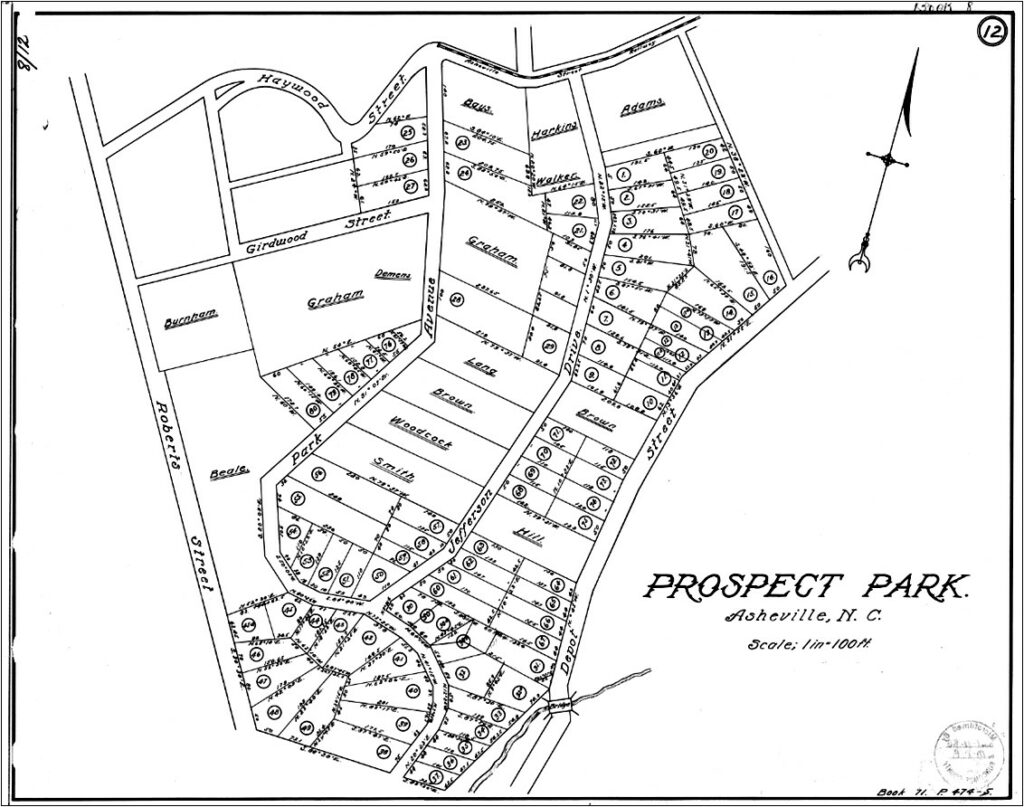

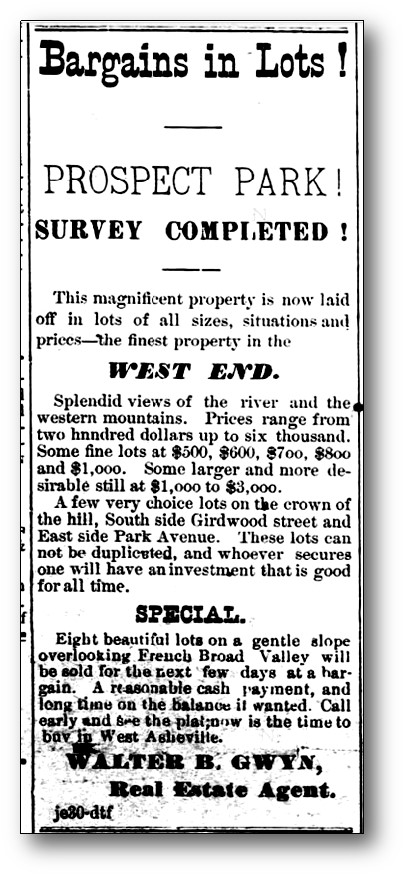

The first advertisement for “Prospect Park” appeared in July of 1887, as the cotton factory was being built. “Bargains In Lots- PROSPECT PARK- SURVEY COMPLETED”, advertised Walter B. Gwyn, Real Estate Agent, in the July 1st, 1887 edition of the Asheville Citizen Times.[22] The advertisement informed the potential property buyer that there were lots “of all sizes, situations, and prices” and that those lots ranged in price from “two hundred dollars up to six thousand”.[23] Further, it was advertised that the lots had “Splendid views of the river and the western mountains”.[24] Interestingly, the survey for Prospect Park[25]was not registered as a plat until 1890, which is probably why it is odd that a lot of the larger lots (or possibly blocks of lots) on the plat have owners names and are not numbered. By July 9th, it was reported that W. B. Gwyn had already “sold about $5,000 worth of lots in Prospect Park, “since his advertisement was inserted in the Citizen.”[26] Obviously written by a newspaper editor, the advertisement ended by encouraging its readers to “Secure a lot in Prospect Park, and never forget to advertise in the Citizen.”[27] Gwyn’s original July 1, 1887 advertisement ran in the Citizen-Times until the end of March of 1888.

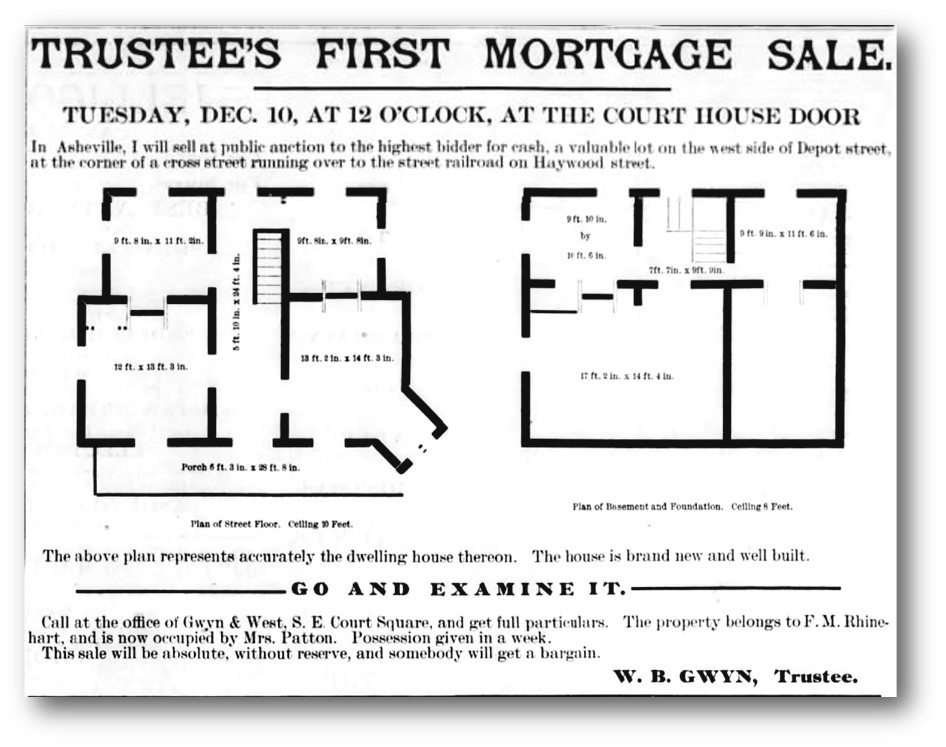

One of the first mentions of any residences being built in Prospect Park appears to be from June of 1888, where it was reported that Gwyn & West had sold a building lot to F. M. Rhinehart, and that Mr. Rhinehart planned to “begin at once to erect a fine brick residence thereon”.[28] Rhinehart built his two-story brick residence on the west side of “Depot Street” (Clingman Avenue) about where is now the Owen Bell Park. However, Rhinehart never lived in the house, and by 1889 he had defaulted on the loan (from Gwyn) and the house had to be foreclosed on and sold to pay back the loan. Although we have no known photo of the house, we do have the floor plans, as they were printed in the sale advertisement.[29] The ten-room house had five rooms on each floor, with the first story having a ten-feet ceiling height, and the second-story, eight-feet ceiling height.

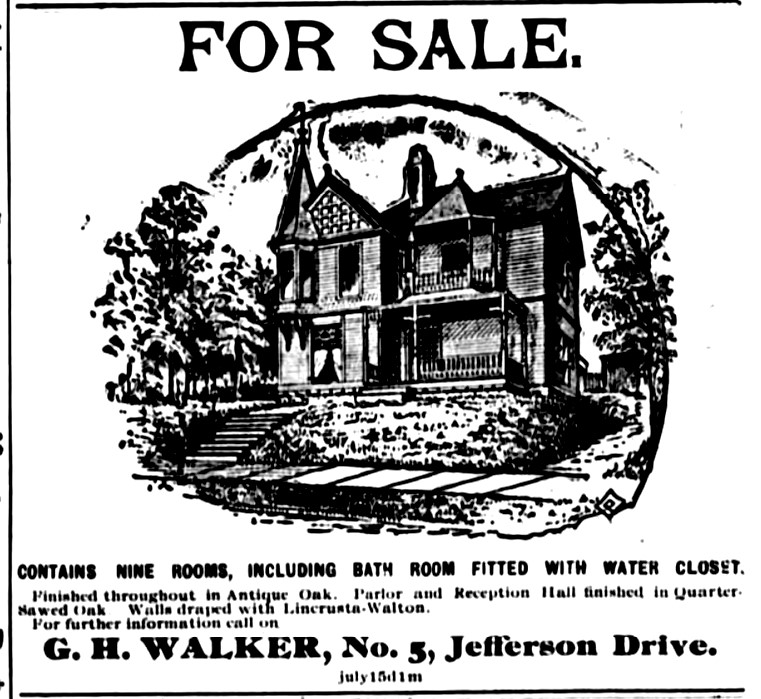

In an 1889 article, “punningly” titled “Prospect Park Prospects”, it was announced that “among the new dwellings now going up in this place is the handsome two-story ornamental residence of superintendent George H. Walker, of the Asheville furniture factory; that of Chas. Miller [Müller] -a lovely cottage of novel design; and several others less pretentious, though nevertheless comfortable and attractive.”[30] Charles Müller built his cottage of “novel design” on the east side of Jefferson Drive, not far from the corner of W. Haywood Drive. George H. Walker built his ornamental cottage on the west side of Jefferson Drive, almost opposite the Müller house. First numbered as 5 Jefferson Drive, it later was known as 15 Jefferson Drive. Unfortunately, neither of these early cottages survive, however we know what Walker’s ornamented cottage looked like from a sketch of the house in a series 1890 advertisements.[31] The sketch reveals that the house was two-story with an asymmetrical front façade containing a projecting two-story gabled bay on the left with a second-story turreted oriel on its corner. The right-side of the façade was balanced with a whimsical two-story porch, on which was the front entrance. The house appears to have been sided with wood shingles with paneled gable ends.

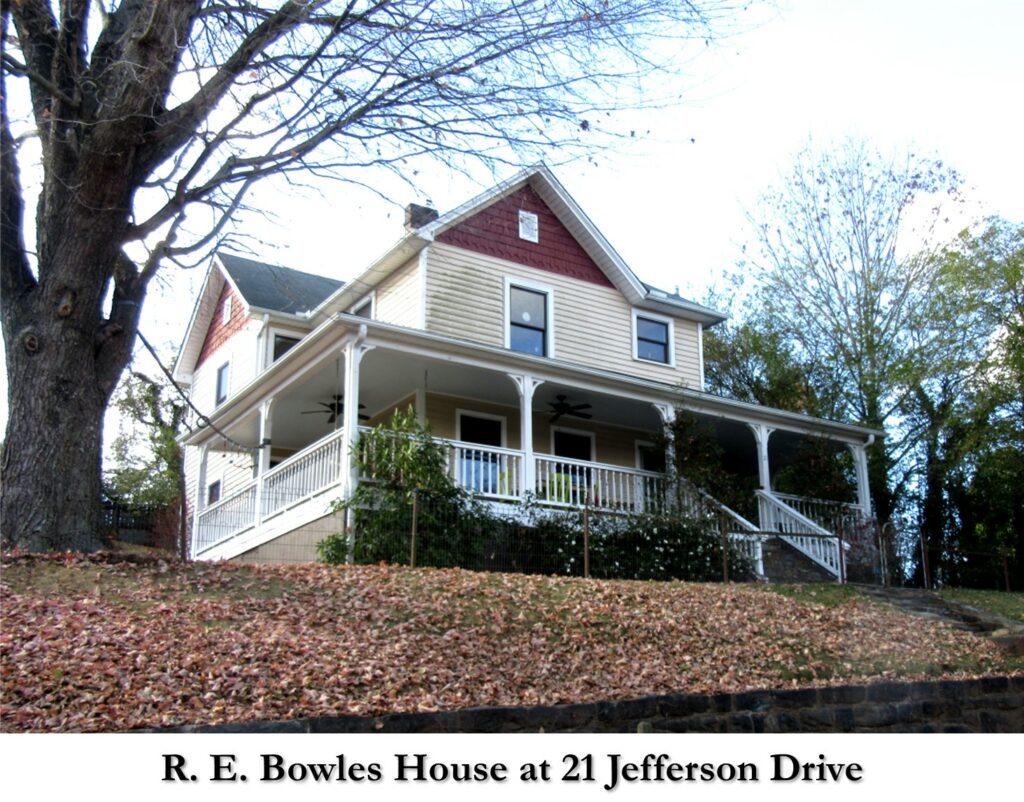

An 1889 account of the development reported that most of the houses being built in Prospect Park, in those first years, had their “front on Jefferson Drive”.[32] Jefferson Drive and Park Avenue were along the ridge and provided the best vistas as homesites. Although the first two cottages mentioned above, are no longer standing, there are a few early Prospect Park houses remaining today on Jefferson Drive. In 1889, painting contractor R. E. Bowles purchased a lot from Gwyn & West on the west side of Jefferson Drive[33], next door to George H. Walker’s house at #5 Jefferson Drive. Robert Eugene Bowles, a native of Virginia had moved to Asheville in 1882. In 1884, Bowles married Malinda C. Turrett, and the following year he purchased a lot on the southside of Haywood Street, just outside of Prospect Park, and built a house at 362 Haywood Street.[34] It was while living there, in 1886 that Bowles got the contract for the painting and decorating of the Battery Park Hotel[35], which was then being erected. Tragically, just four years after their marriage, R. E. Bowles’ young wife Malinda suddenly died.[36] The following year, 1889, Bowles remarried to Marie Louise Drake,[37] and then in December of 1889 Bowles purchased the lot on Jefferson Drive to build a new family home. On his newly purchased lot, which was originally addressed as #7 Jefferson Drive (now 21 Jefferson Drive), R. E. Bowles built a simple but attractive two-story house, similar in shape and massing to the Walker house next door, except that Bowles cottage had a wraparound front porch.

Another early Prospect Park house that remains, also on Jefferson Drive, is the house at 24 Jefferson Drive. In 1888, Gwyn & West sold a lot on the east side of Jefferson Drive to carpenter, Charles M. Hampton.[38] Since the registered plat for Prospect Park was not made until 1890, the description of the lot sold to Hampton does not contain a lot number, however from further descriptions, it appears that Hampton purchased what would later be labeled on the Prospect Park plat as lots 2 and 3. He built his house on the southern portion of his lot (later called lot 3) and sold off the northern part of the lot (later called lot 2) in 1890.[39] On his new lot, which was on the downhill side of the street, Hampton built what appears from the street to be a one-story house, but is in fact a two-story house with the lower story being below the street level. Hampton built his house as a quintessential late-nineteenth century “cottage”- small, ornamented, under a steeply pitched hipped roof, with an asymmetrical projecting front gable, and featuring a full façade front porch. Renovated in recent years, the house has been turned into a two-family dwelling (duplex).

Another early Prospect Park house that remains, also on Jefferson Drive, is the house at 24 Jefferson Drive. In 1888, Gwyn & West sold a lot on the east side of Jefferson Drive to carpenter, Charles M. Hampton.[38] Since the registered plat for Prospect Park was not made until 1890, the description of the lot sold to Hampton does not contain a lot number, however from further descriptions, it appears that Hampton purchased what would later be labeled on the Prospect Park plat as lots 2 and 3. He built his house on the southern portion of his lot (later called lot 3) and sold off the northern part of the lot (later called lot 2) in 1890.[39] On his new lot, which was on the downhill side of the street, Hampton built what appears from the street to be a one-story house, but is in fact a two-story house with the lower story being below the street level. Hampton built his house as a quintessential late-nineteenth century “cottage”- small, ornamented, under a steeply pitched hipped roof, with an asymmetrical projecting front gable, and featuring a full façade front porch. Renovated in recent years, the house has been turned into a two-family dwelling (duplex).

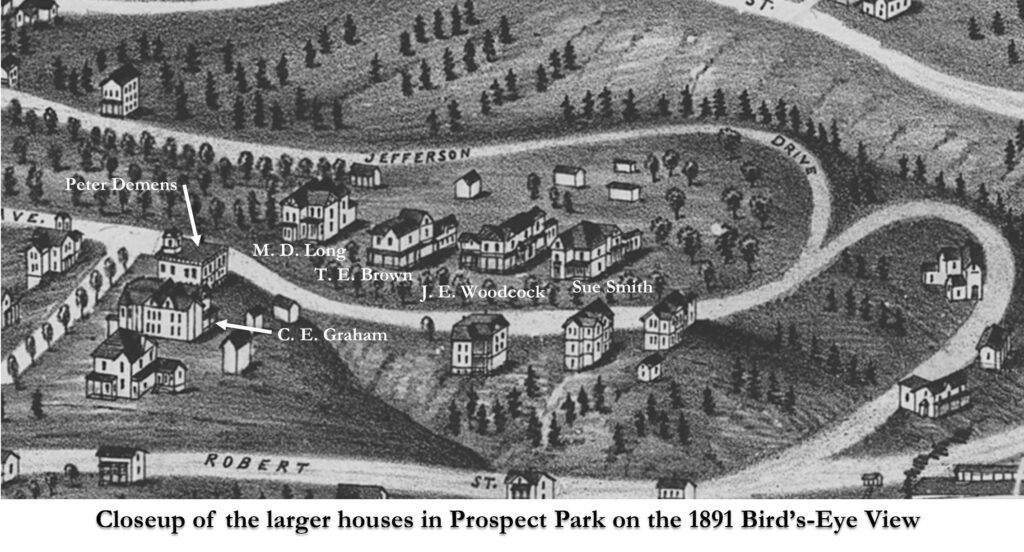

The 1891 Bird’s-eye view map of Asheville shows that Prospect Park had a slow start, with houses first being built only on the northern portion of Jefferson Drive and on the south-western portion of Park Avenue. The larger houses were those built on the east side of Park Avenue on top of the knoll, facing west, as they were the premier lots, being both flat and having stunning views of the mountains to the west and south. Although all those four large houses on Park Avenue are long gone, we have vintage photos that show individually, two of the four large houses. However, we do have the 1891 Bird’s-Eye view map and the 1912 Bird’s-eye map to show us what the houses looked like, and using those maps as well as the Sanborn maps, we can identify the two houses for which we have images of. The first house that we have an existing photo of is merely labeled as being on Park Avenue.

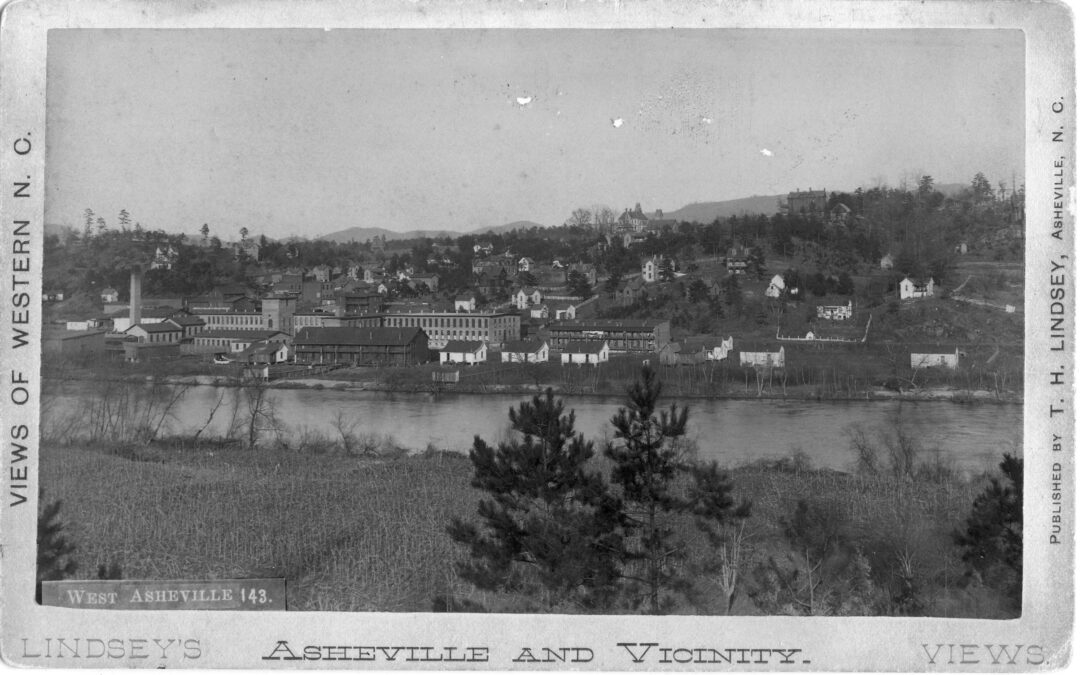

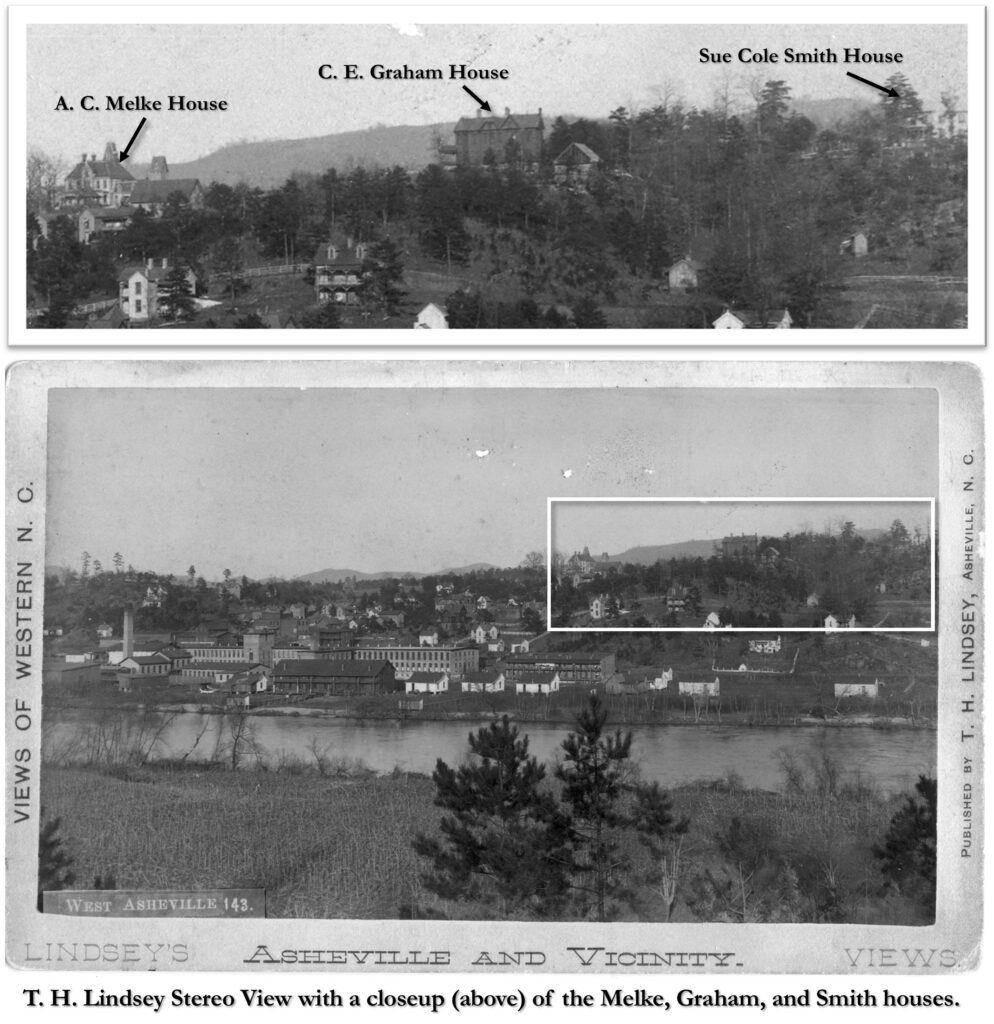

A c1890 stereo view photo, by T. H. Lindsey, titled “West Asheville” #143, part of his “Asheville & Vicinity, Class A, Views of Western N.C” shows what is now called the “West End” area of Asheville. Ironically, the photo was taken from the bluff on the west side of the French Broad River in what in NOW called “West Asheville”, looking east toward the eastern shore of the river. This inclusive photo includes many houses from the early development of Prospect Park and Factory Hill. In this photo, we see a partial image of another of the four prominent houses built on the east side of Park Avenue. At the top of the photo on the far right, a light-colored house shows partially covered by a large tree. The angled front porch was a key element in identifying this house. It appears to be the house built in 1890, on the east side of Park Avenue at 102 Park Avenue (later addressed as 76 Park Avenue) for Mrs. Sue Cole Smith.[40] The house was built during the Spring of 1890 for “Mrs. Smith” by architect/builder Milton Harding. At the time, Milton Harding, in partnership with Prospect Park resident Peter Demens, was building a new U. S. Federal Post Office on Patton Avenue (at what is now called Pritchard Park) in downtown Asheville. In a May 1890 newspaper Milton Harding reported that the house he was building for “Mrs. Smith”, “has ten rooms and is finished in natural pine” and that “It cost $4,000”.[41] From the photo and the Sanborn maps, we also can see that it was two-stories and had an ornamented angled front porch. Mrs. Sue Cole Smith was the wife of Presley Nelms Smith, a prominent grocer of Salisbury, NC. Mrs. Smith used the Asheville as a retreat/vacation home, renting it out most of the time. The house survived until it was badly damaged by fire in 1936. It was apparently torn down shortly thereafter, as the only listing in the 1937 Asheville City Directory was for 76 ½ Park Avenue, which was a small 3-room house behind the main house. The property has recently been subdivided and is the site of new modern infill houses.

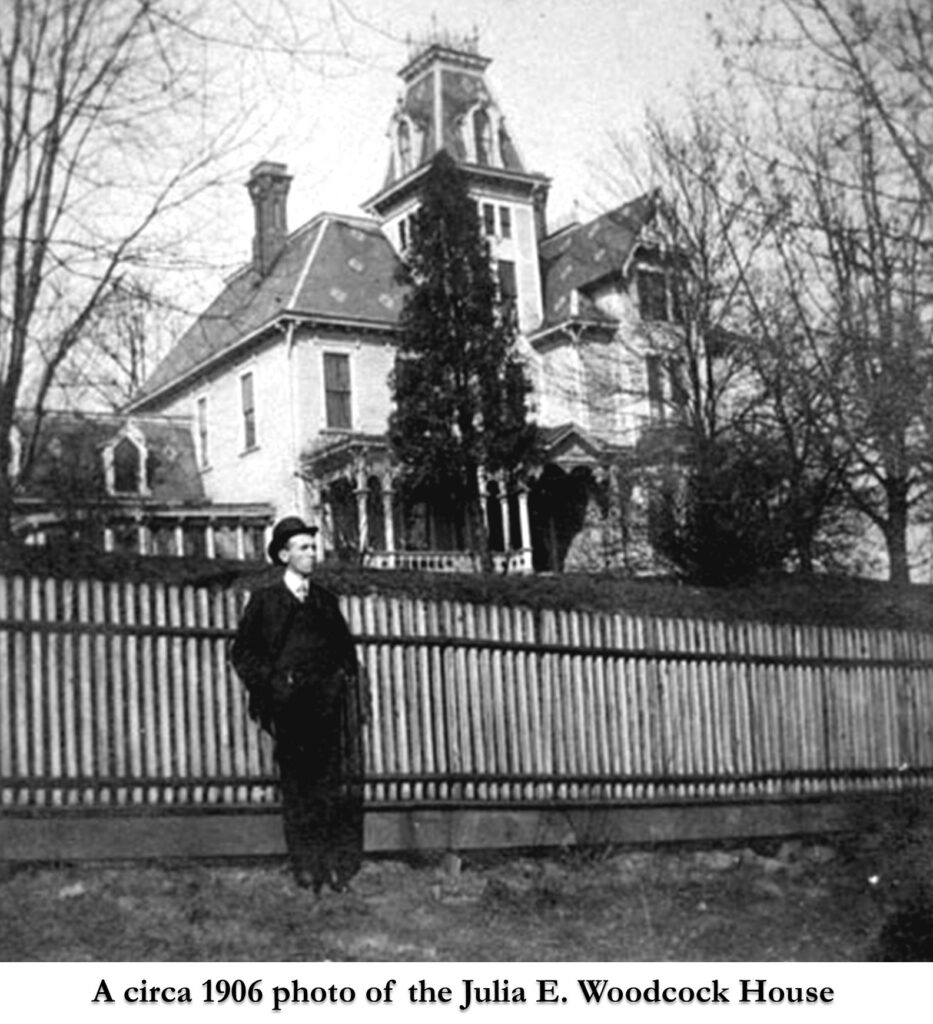

A c.1906 photo appears (by comparison to the Bird’s Eye View, Sanborn Maps and other sources) to show the house that Mrs. Julia E. Woodcock had built in 1887 at what was first addressed as 78 Park Avenue and later 68 Park Avenue.[42] The highly ornamented house with its four-story center tower and ornamental slate roof, though now thought of as the quintessential “haunted house” look, was in its day a showcase of high Victorian style and taste. This was the only house remaining on the east side of Park Avenue shown on the 1951 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. Unfortunately, the house was demolished in 1969, following a citation for being a neglected, “unsafe and dilapidated” building.[43]

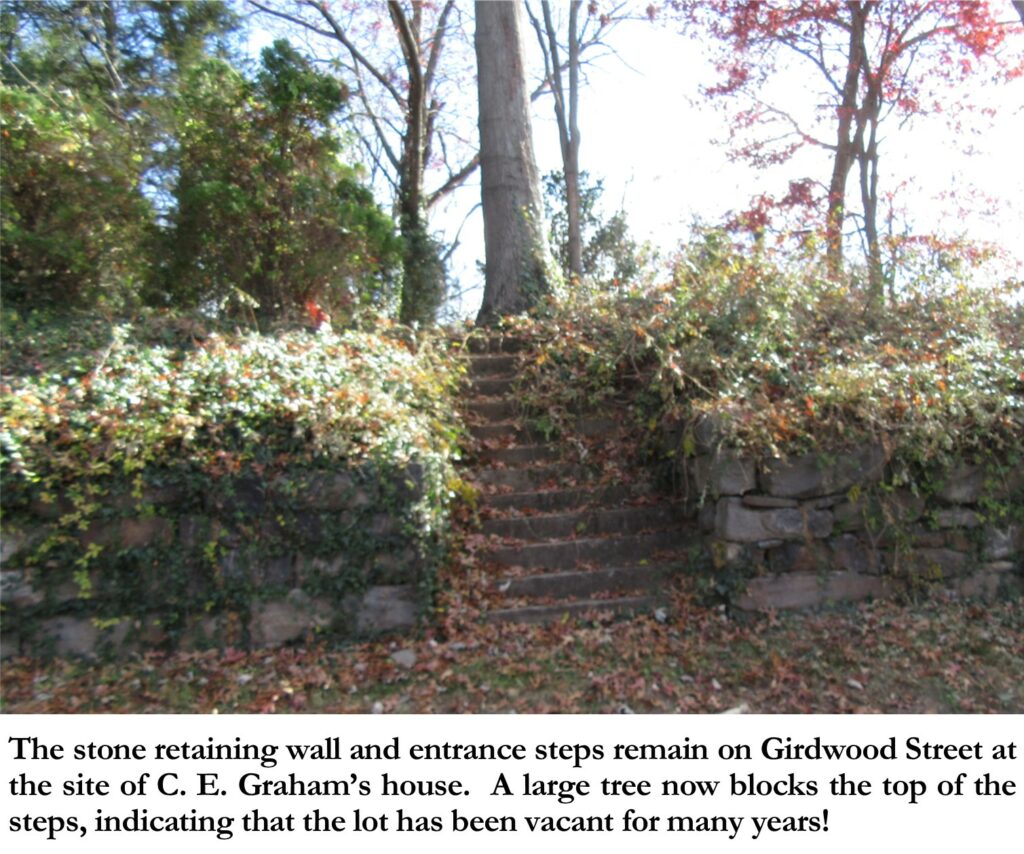

C. E. Graham’s large house was one of the first, if not the first house to be built in Prospect Park. It is one of the prominent houses built early on in Prospect Park, which also shows in the 1890 Lindsey photo. Graham, despite buying a block of land, had chosen a small lot just south of Park Avenue for his new house. On it he built a two-and-a-half story frame house, with a rubble stone basement. The house’s front façade faced what was then called Park Place (now called Girdwood Street). The Graham house, which is shown in the center top of the Lindsey photo shown above, appears to have been painted in somber dark Victorian “earthy” shades (such as burnt sienna, tan, clay etc.). A shed/carriage house, which appears to be under construction, shows to the right corner (southwest) of the house. Although its footprint plan shows on several of the Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, this seems to be the only photographic image that we have of this imposing house. The C. E. Graham house, which was addressed as 20 Park Place, was gone by 1951 (it does not show on that year’s Sanborn Map). Not only has it never been replaced, but its front yard stone retaining wall and entrance steps remain. A large tree now blocks the top of the steps, indicating that the lot has been vacant for many years!

As early as 1891, this area of Asheville, on the “West End” had been targeted for development as a “working class” neighborhood. This type of development today is advertised using phrases such as, “Affordable Housing Units” or “Opportunity Zones”, but in the nineteenth century the advertising was clearer about its targeted audience. “GIVE THE POOR MAN A CHANCE”, advertised Richmond Pearson, on June 16, 1891, “UNHEARD OF TERMS FOR THE PURCHASE OF A HOME.”[44] Pearson was selling five lots on Spring Street in front (northwest) of the “Melke place” (a house just across Haywood Street from the intersection of Park Avenue) at the top of “Factory Hill” or “Chicken Hill”. The lots could be purchased with $50 down, with the balance being paid off with “no interest” in “50 Equal Monthly Payments”.[45] Built prior to the development of Prospect Park and Factory Hill, the A. C. Melke prominently shows in the 1890 Lindsey photo. The large towered Victorian gothic mansion shows just to the left (north) of the Graham house on W. Haywood Street. Much of the land that Richmond Pearson purchased in 1883 from J. L. M. Burnett, and then sold to C. E. Graham Manufacturing in 1891 to build the mill village on Factory Hill, was just in front of the Melke house to the northwest. A. C. Melke died in 1891 and left his house and surrounding four acres to Wake Forest College, who in turn sold the house in 1895 to the Asheville Cotton Mills to serve as the home of its Treasurer, Dr. George A. Mebane. [46] The Melke House, addressed as 408 W. Haywood Street, survived until the 1930’s. It was replaced in 1938 by the Patton Avenue Baptist Church, which was renamed the Haywood Street Baptist Church in 1963. But alas, the church was demolished in 1968, as the property was taken for highway construction.[47]

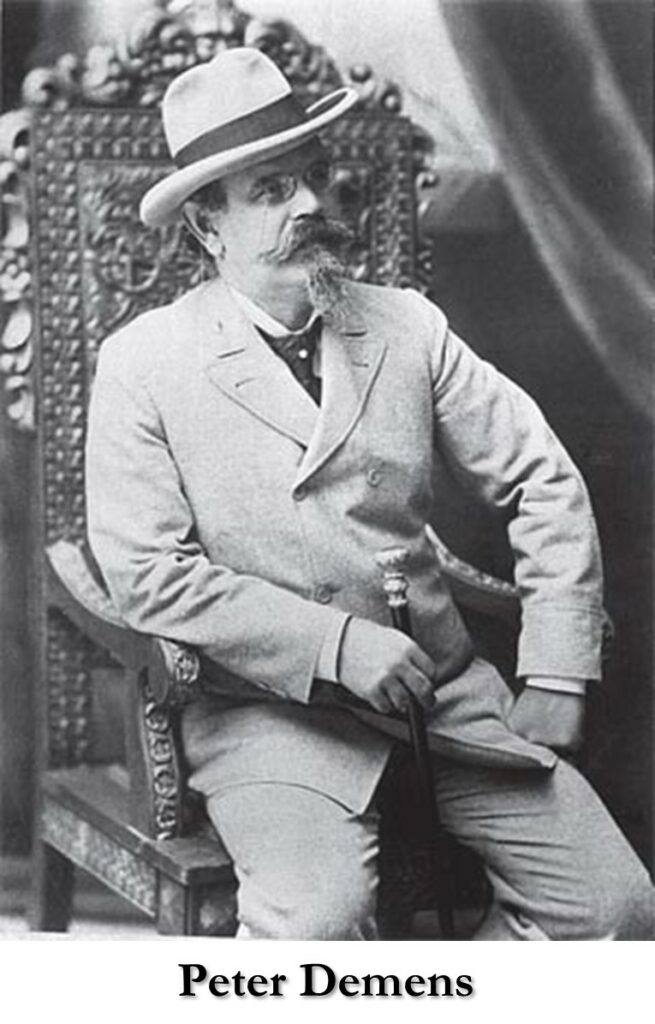

The only original of the larger Prospect Park mansions that remains today, that showed on the 1891 Bird’s Eye View is the unique two-story brick house built in 1890 by the enigmatic Russian-born entrepreneur Peter Demens. Born, Pyotr A. Dementyev in Russia in 1850, Peter Demens was a Russian nobleman who emigrated to the United States in 1881, first settling in Longwood, Florida where he invested in a lumber and construction business. In 1885 Demens was supplying railroad ties to the narrow-gauge Orange Belt Railway. When the railroad could not pay its debts, Demens took over its charter. As owner of the railroad, Demens extended “its lines to link Kissimmee with Jacksonville and Tampa Bay”. In 1888, when the railroad extension reached its terminus in southern Pinellas County, Demens named the Depot (and its ensuing town) “St. Petersburg” Florida. In July of 1889, Peter Demens moved to Asheville, where he propositioned the city leaders that if a suitable lot for a wood-working factory site “was donated by the people of the city, or any of its citizens”, that Demens would “immediately leave for Philadelphia to purchase all necessary machinery for the enterprise”.[48] A committee was formed, including among its members, C. E. Graham, to search for a “suitable” site.[49] On August 3, 1889, the local newspaper reported that “the money has been raised, the location decided on, and the machinery bought for the new woodworking factory of Demens & Taylor of this city”.[50] Construction began shortly thereafter, on a site just south of the railroad depot, under the superintendency of the equally enigmatic “H. W. Fitch”[51], and operation of the new factory began in October of 1889.

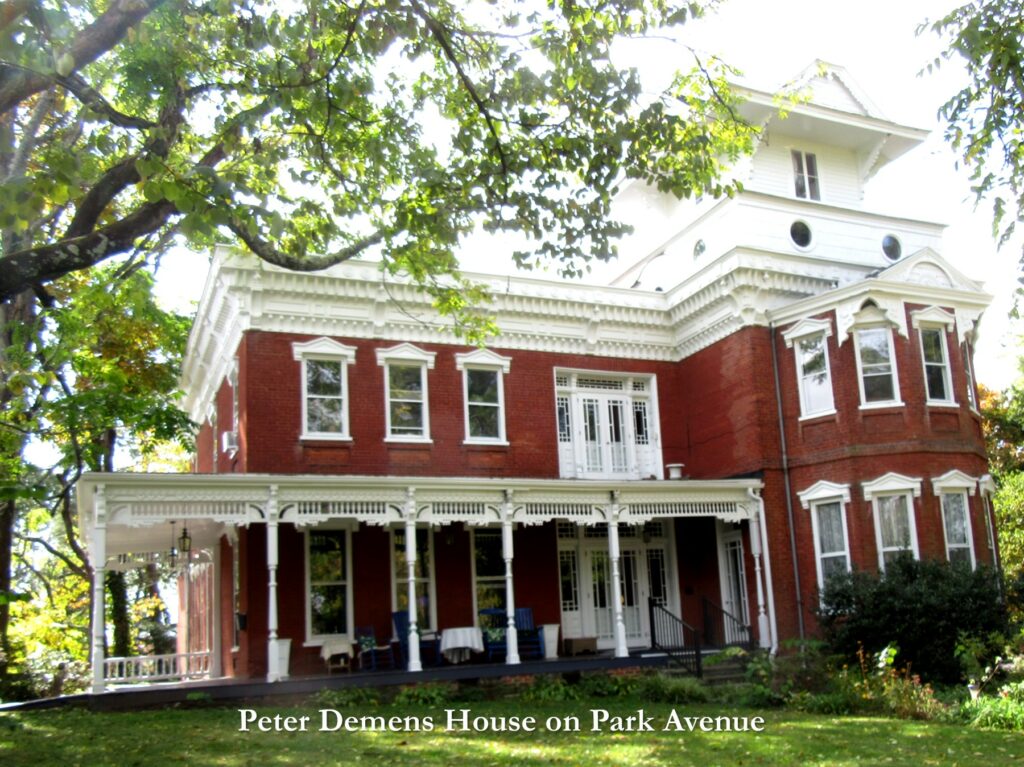

In May of 1890, Peter Demens and his wife Raisse L. Demens, purchased a lot on the west side of Park Avenue in Prospect Park from C. E. & Susan Graham.[52] The Graham’s had already built their mansion house on the adjacent lot to the west, facing Girdwood Street. On his lot, now addressed as 31 Park Avenue, Peter Demens built a large two-story brick house with a unique highly ornamented cornice, flat (ish) roof, and three-story tower. Though it almost defies being categorized as any specific “style”, the Demens house is generally of the Italianate Style. Perhaps built as a “showroom” house, the house proudly and blatantly functioned as a showcase for the capabilities of the Demens proficiency on producing varied wood products. Also, Demens’ Russian heritage is displayed by the three-story tower which, though lacking an “onion dome”, appears to have been inspired by Byzantian architecture. “The heavily carved and paneled interior woodwork, which includes rich parquet floors, is among the most remarkable of the period in the state and was installed to showcase the work of P. A. Demens Woodworking Company.”[53] Demens did not live in the house for very long, as after two failed construction projects (which Demens took on in partnership with builder Milton Harding) to contract the building of two Federal post offices in Asheville and Statesville, NC, he decided in 1892, to sell the house and the P. A. Demens Woodworking Company to Col. J. H. Rumbough[54], and move to Los Angeles, CA. The Demens house, whose story is told elsewhere, still survives today, in much of its original condition, and is now listed (since 1982) on the National Register of Historic Places.

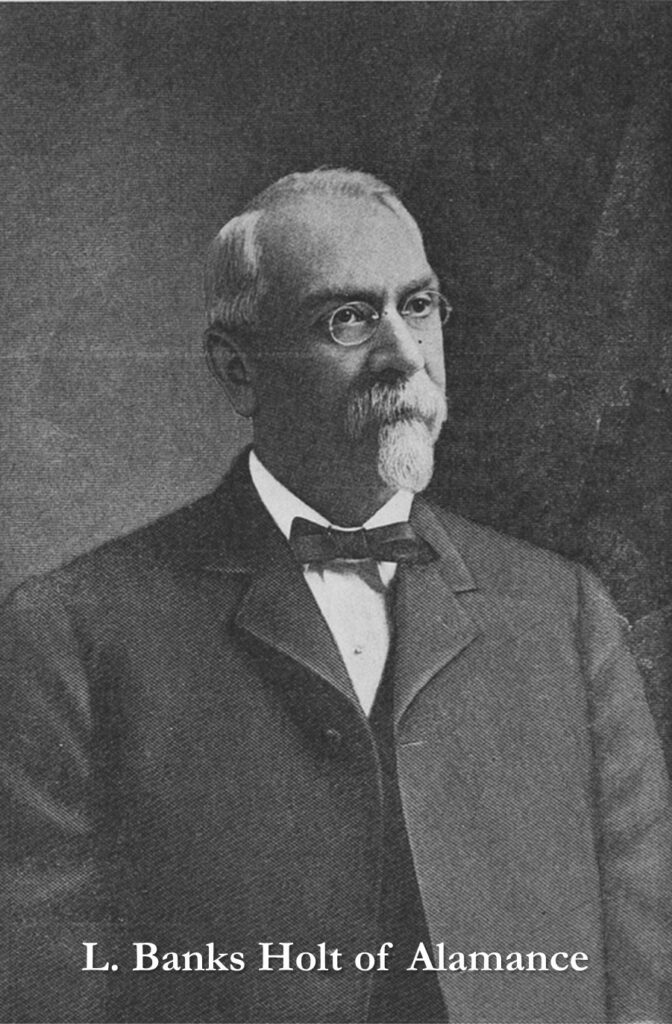

In June of 1890, just a few months after selling one of his lots to Demens, C. E. Graham joined a “syndicate” of men, including the original owners, W. B. Gwyn and W. W. West, that purchased the remaining lots of the Prospect Park Company.[55] As the syndicate was buying the remaining lots of Prospect Park, the newspaper reported that “there are already some handsome residences on the property, among them Mr. C. E. Graham, Mr. Demens, Mr. Winburn, and Mrs. Woodcock.”[56] All of those mentioned were on the top of the slope, on or just off of Park Avenue. The following year, 1891, C. E. Graham sold his magnificent house on Park Place (Girdwood Street) to P. F. (Preston Fidelio) Patton.[57] However, like Demens, C. E. Graham was soon to shift his capitalistic ventures away from Asheville. In 1892, the same year that Demens sold out, C. E. Graham sold his interests in the “C. E. Graham Manufacturing Company”, which owned and operated Asheville Cotton Factory, to L. Banks Holt of Alamance, NC.[58] At the same time, C. E. Graham, and his brother W. J. Graham, re-purchased the “Huguenot Mills” in Greenville, SC from the Fulenwider brothers.[59]

Let me take a moment to correct a bit of misinformation that has been circulated over the years, concerning the relationship of the Cone family of Baltimore, MD to the Asheville Cotton Mills. It’s been mistakenly written and rumored that the Cone Brothers, Moses H. and Ceasar Cone, purchased the Graham cotton mill in 1893 from Graham, and changed the name to the Asheville Cotton Mills. However, that was NOT the case. In 1893, C. E. Graham surprised everyone by forming a new company called the “Graham Manufacturing Company”, with partners: J. E. Dickerson, R. U. Reeves, and M. E. Carter[60]. Graham and his new company further announced the construction of a new cotton weaving mill to be built south of the old depot. Not only was Graham building another cotton mill in Asheville, but his new company name was very similar to his former company which still existed and was then the owners of his former cotton mill. No doubt this move is what prompted the “C. E. Graham Manufacturing Company”, of which Graham no longer held an interest in, having sold his interest in 1892, to officially rename their company the “Asheville Cotton Mills”.[61] As mentioned previously, in 1892 Graham had sold his half interest to L. Banks Holt, not to either of the Cone brothers. Moses H. Cone and Caesar Cone were ALREADY part owners of the company and mill, having been among the original investors and Board of Directors of the “C. E. Manufacturing Company” since 1888. Moses Cone was even elected President of the company in 1890, while C. E. Graham served as Treasurer. The Cone brothers were the sons of Herman Cone (originally Kahn) & Sons of Baltimore, MD, which was one of the largest wholesale grocery firms in the country. C. E. Graham had previously had business dealings with the firm when he too was operating a wholesale business in Asheville in the early 1880s. Graham had approached the Cones to invest in his new cotton factory in 1888. Another brother, Fred Cone would join the Asheville Cotton Mills in 1901.

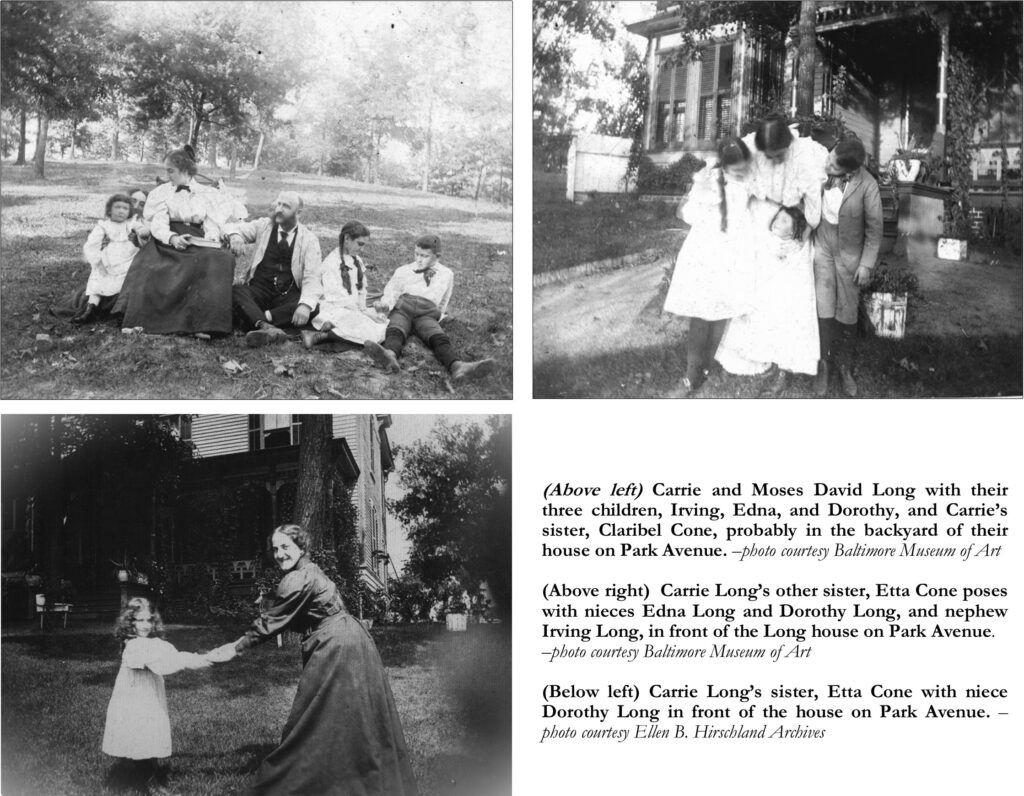

Another member of the Cone family that joined C. E. Graham Manufacturing early on, was Moses Cones’ brother-in-law, M. D. (Moses David) Long. Long, who had married Carrie Cone Long in 1884, would be the first of the Cone family to establish a permanent residence in Asheville, in 1888. [62] That was when M. D. Long bought out C. E. Graham’s interest in the Graham Shoe Factory, becoming the Vice-president of the factory, with Graham’s brother, R. L. Graham acting as President. Upon moving to Asheville in 1888, Long first rented the house at 50 Park Avenue that had recently been erected by J. W. Wadsworth of Charlotte, NC. In 1889, Long’s brother-in-law, Moses H. Cone, purchased the house from Wadsworth, no doubt as the Cone family home for when he or his brother would visit Asheville. The deed from Wadsworth to Cone specifically mentions that the property included “the dwelling house now occupied by M. D. Long”.[63] So he also may have bought it specifically for his sister and her husband. Almost ten years later, in 1897, Moses Cone officially deeded the house to his sister, Carrie Cone Long.[64] M. D. & Carrie Long became lifetime residents of Asheville. A few years after working with the shoe factory, M. D. Long opened a department store, called “M. D. Long’s” as a commissary of the Asheville Cotton Mills. In 1910, Long sold his store and joined the Asheville Cotton Mills as Secretary-Treasurer. The Longs owned and occupied the house at 50 Park Avenue until Carrie Long’s death in 1927, at which time M. D. Long went to live with his daughter’s family and the house was sold.[65] M. D. Long died in 1936. The house survived until 1971, at which time it was sold to the Pioneer Welding Company[66], as part of the site for their relocated business. The site is now occupied by modern in-fill residential housing. The Cone family would eventually own the primary interest of the Asheville Cotton Company. And although they would go on to be the premier Textile Manufacturers during the nineteenth and early twentieth century, owning and establishing many textile mills in the south, we must remember that they got their start in the textile business in Asheville as partners of “C. E. Graham Manufacturing”!

Although Graham did build his second cotton mill in 1893, further south of the depot on the French Broad River, near the “French Broad Lumber Company”, it only operated for a few years before becoming defunct. By 1896, the new cotton mill was not only out of production, but it was reported that the walls of “the old C. E. Graham Factory, near the French Broad mills” were “being torn down”[67]. Perhaps that’s why in 1896, Graham decided to permanently leave Asheville and move to Greenville, SC where his could concentrate on his interests in the “Huguenot Mills”, which he still owned.

Under its new name, the Asheville Cotton Mills continued to prosper and grow, and so the developments of Cliveden Park, Prospect Park, and Factory Hill continued to grow as well, into working-class neighborhoods, providing homes for the workers and the management staff.

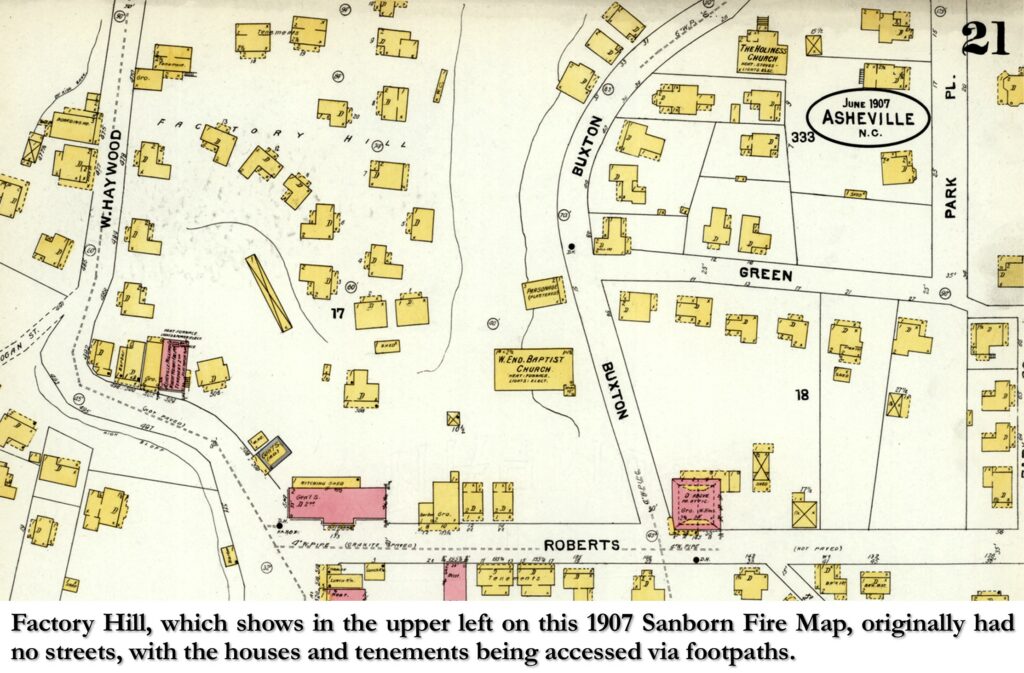

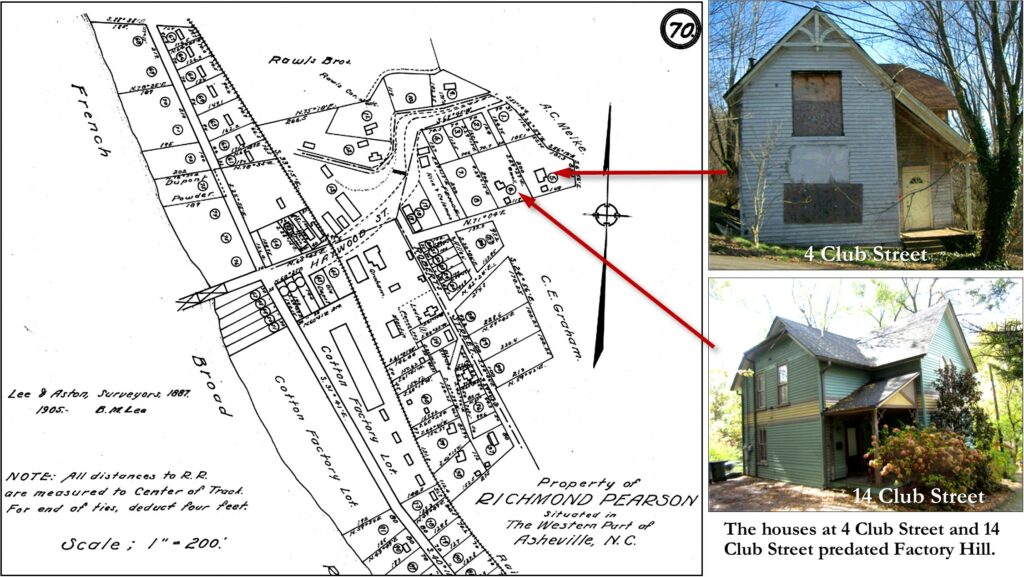

“Factory Hill” or “Chicken Hill”, also described in 1901 as “Asheville’s Mill Colony”, occupied the area on the hillside above the Asheville Cotton Mills, bounded by “Buxton Street on the east and southeast, and Spring Street on the north.”[68] In 1901 it was reported that “three hundred and fifty people are employed in the mill and most of these have their homes in the mill colony on the hill, above their working places, or along the banks of the river.”[69] “Factory Hill” began in 1891 when C. E. Graham Manufacturing Company, owners of the Asheville Cottom Mill, purchased for Sixteen thousand dollars, “Lots 1,2,3,4,5,6,7, & 8” of the Richmond Pearson lands[70], as represented on an 1887 plat (which was redrawn and recorded in 1905).[71] Although it’s unclear how many cottages were first built on the hill in 1891, by 1907 there were over twenty numbered houses and three or four tenement (apartment) buildings. The purpose of establishing “Factory Hill” in 1891, was not only because additional factory housing was needed, but also because the factory’s original houses and tenements, built on the flat lands next to the mill, had been perilously threatened during a flood in February of 1891,[72] and the company felt the need for housing on higher ground.

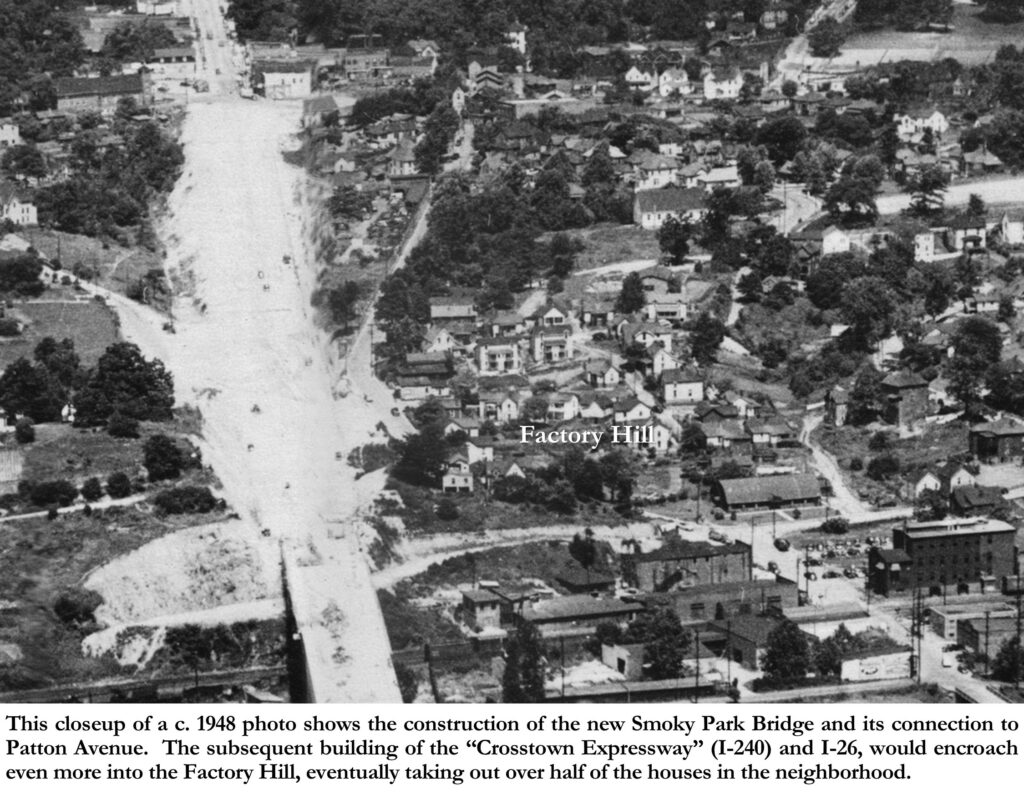

Originally the houses and tenements on Factory Hill, though grouped together, were not separated by roads or driveways, and had communal latrines, and a community bathhouse. The houses and tenements were all owned by the company (C. E. Graham Manufacturing; later Asheville Cotton Mills) and leased to their operatives. In 1944, the company decided to divest themselves of the houses and began selling them to the employees (through a payroll deduction system). A few roads, like Trade Street and View Street were graded out for easier access to the houses. However, by 1954, the neighborhood was already in decline. The building of the Smoky Park bridge in 1950, took out about half of the Factory Hill community, followed in 1953 by the closing of the Asheville Cotton Mill, which left the remaining homeowners unemployed. From the closing of the mill until around 2000, the neighborhood suffered further decline.

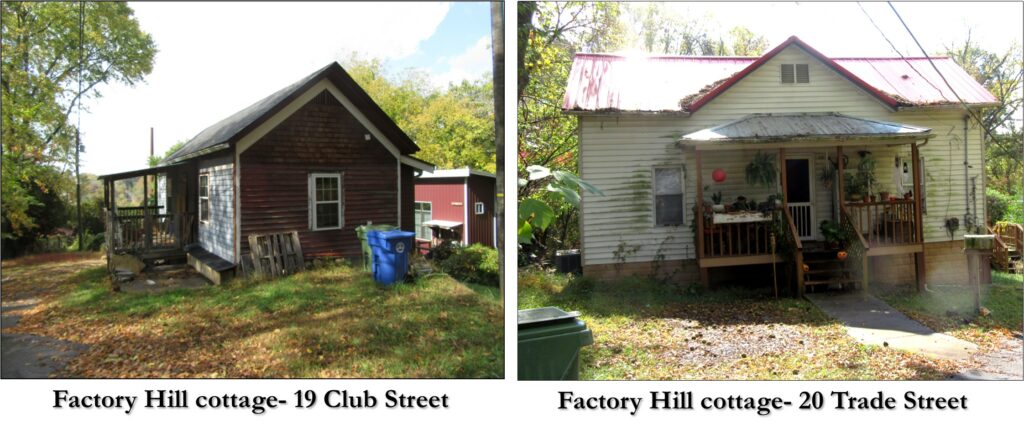

The house at 14 Club Street, which was one of the Factory Hill houses used to house mill workers, survives and has recently been restored, sporting a period polychromatic exterior paint scheme. The house was originally known as cottage “No. 7 Factory Hill”. In the 1981 edition of Cabins and Castles, which included descriptions of structures from a countywide architectural survey, author and architectural historian, Douglas Swaim notes that the house at 14 Club Street, along with a similar house at 4 Club Street, as being of “considerably higher quality than the mill’s other housing”.[73] Swaim suggests that they were built as private residences and probably by the same builder/architect. This is a possibility as the surviving house at 14 Club Street, with its triangular arched front windows, turned porch posts, stick-style detailing, along with its steep and truncated gables seems a product of the 1880’s. This is also a possibility as the Pearson Plat of 1887 shows that there were two existing houses, one on lot 5 and one on lot 6 of the eight lots that C. E. Graham Manufacturing purchased from Pearson in 1891, to establish the Factory Hill village. The house at 4 Club Street, though not as ornamented as the house at 14 Club Street, had similar massing and similar details. The house at 4 Club Street no longer survives.

According to the early twentieth century Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, the standard mill house built on Factory Hill was an unornamented one-story ell-shaped house with a small center front porch. Two examples (and almost the only surviving examples) of original Factory Hill mill houses are just across the street from the 14 Club Street house, at 11 Club Street and 21 Club Street. Though both cottages have been altered, they still maintain their original L-shaped original. The house at 20 Trade Street, next door to 14 Club Street, is another original Factory Hill worker’s cottage plan than those on Club Street, though of a simpler The other type of mill housing built on Factory Hill was the tenement houses which were two-story (built against the slope) and located at the top of the hill. None of them survive.

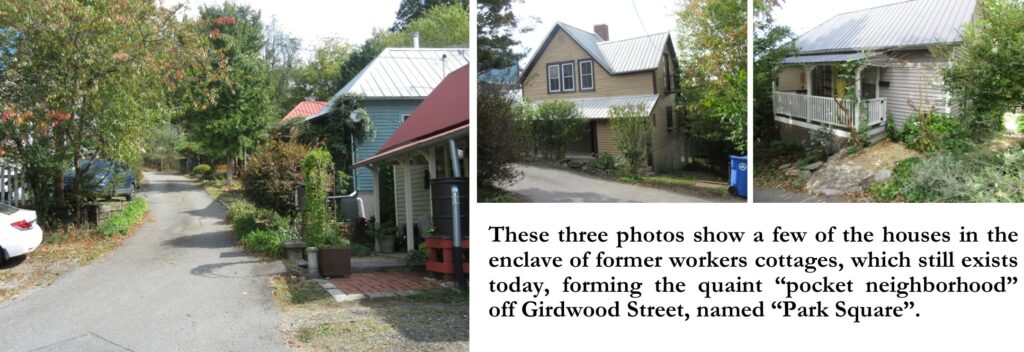

The previously mentioned 1901 newspaper article, titled “Asheville’s Mill Colony”, also reported that “On the bluff directly east of the mills the company has recently built 12 or 13 comfortable cottages, which are rented to the operatives [employees]”.[74] These were the cottages that the Asheville Cotton Mills had begun to build in the summer of 1900,[75] which I surmise were the small enclave of cottages built around in the southwest corner of Prospect Park, below the Demens and Graham houses. This entire enclave of workers cottages still exists today, forming a quaint “pocket neighborhood” off Girdwood Street, named “Park Square”.

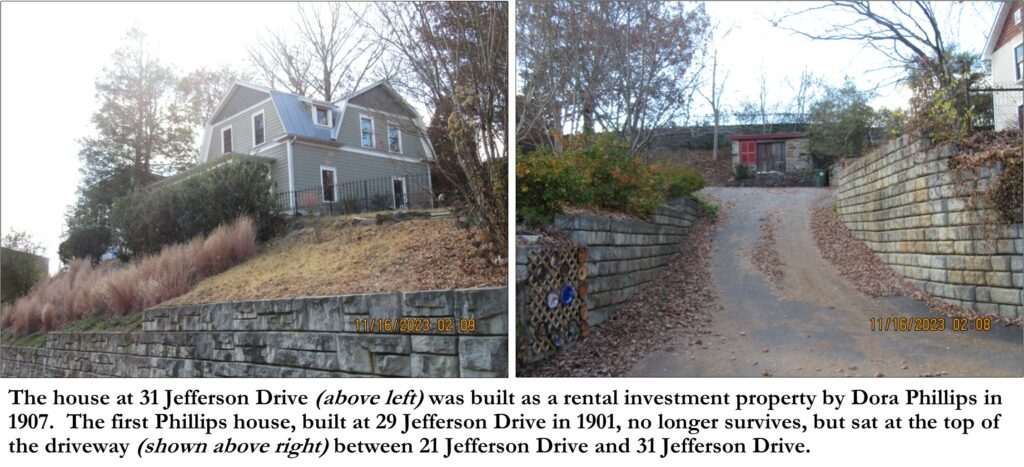

Prospect Park continued to grow and populate into the first two decades of the twentieth century. In 1900, Samuel H. Phillips, a railroad car inspector, and his wife Dora Phillips began leasing the house next door at 7 Jefferson Street (R. E. Bowles house) and operating it as a boarding house. In 1901, the Phillips purchased the adjacent lot at 9 Jefferson Street[76], and built a two-story frame house, that was first addressed as 9 Jefferson Drive. The house that the Phillips built at 9 Jefferson was larger than their leased quarters, and upon completion it opened both as their home and as a boarding house, catering to working men and women. The house was re-addressed as 29 Jefferson Drive in 1907. 1907 was the same year that Dora Phillips decided to expand her entrepreneurial business by building an investment property (rental house). Dora purchased the lot adjacent to (on the south side) her boarding house,[77] and built a two-story house with cross gambrel-roofed gables, and a large front porch. This house was addressed (and still is) as 31 Jefferson Drive. Being on the downslope of Jefferson Drive, the house at 31 Jefferson Drive was built up on top of the slope above a large stone retaining wall at the street. Unfortunately, Dora Phillips died in 1917, at the age of 43, leaving Samuel and two surviving children, Thelma and Clinton. In her Will, Dora left the two houses to her children- Clinton, who was only 7-years old, inherited the lot and house at 29 Jefferson Drive, and Thelma, who was 17 years old, inherited the lot and house at 31 Jefferson Drive. Dora’s husband, Samuel H. Phillips was granted a “life interest” in the properties “providing he remain unmarried”.[78] However, Samuel remarried in 1919, and moved his new wife into the house at 29 Jefferson Street. Almost immediately the will was challenged- Thelma Phillips vs. Clinton Phillips. And in 1921 the Superior Court ordered that the house at 31 Jefferson Drive was to be sold, with S. H. Phillips acting as commissioner of the court. At that time the house at 31 Jefferson was sold out of the Phillips family to O. W. Cooper.[79] In 1922, Thelma Louise Phillips, at the age of 23, married 36-year-old railroad worker Burton Clinton Means.[80] After their honeymoon, the Means moved into the house at 29 Jefferson Drive. Samuel Phillips, his new wife Sallie, and son Clinton Phillips, upon Thelma’s marriage, moved out of 29 Jefferson Drive to 109 Michigan Avenue. Unfortunately, in 1925, Thelma’s husband died as a result of an incident at work (he fell down a flight of stairs).[81] Thelma then moved from the house to live with her father and brother on Michigan Avenue. The house was leased out, but in 1931, Thelma Phillips Means married Odie C. Bryson, a railroad engineer. That same year she sold her interest in the house at 29 Jefferson Drive to her brother Clinton B. Phillips,[82] and less than two years later in 1933, Clinton sold the house to R. T. Cecil,[83] of Cecil’s Business College. By 1936 the house at 29 Jefferson Drive appears to have been gone and from then on, the lot was combined with the house at 31 Jefferson Drive. The house at 31 Jefferson Drive remains today and is lovingly maintained, and the lot at 29 Jefferson Drive serves as a shared driveway and parking for 31 Jefferson Drive and its neighbor at 21 Jefferson Drive (the R. E. Bowles house).

As Prospect Park and Factory Hill began to grow at the turn of the twentieth century it became apparent that a new school was desperately needed. A “Factory School” had been started around 1897, as a charity school for the children of the “Factory District”. The school was started by the Asheville Flower Mission, a lady’s society that was also responsible for the establishment of Asheville’s Mission Hospital. In 1896, Mrs. L. A. Farinholt (Fanny C, Farinholt), a former teacher at the city’s Orange Street School, then one of the officers of the Flower Mission, began a movement for the establishment of a school in the factory district. In a letter read to the Asheville Board of Alderman, at their November 1896 meeting, Mrs. L. A. Farinholt reported that “there are 149 children between the ages of six and 16 in the factory district who do not attend school because of their living so remote from the school buildings”.[84] The letter was read Thos. A. Jones who was the representative of the Flower Mission, who were requesting a $25 a month (for five months) appropriation from the city to the Flower Mission to establish a school in the factory district. In December the city announced that “they could not recommend the expenditure of money from the public-school funds for the support of a school in the factory district”.[85] Not to be daunted by the Board of Alderman, the Flower Mission continued their campaign the following month, by appealing to the citizenry of Asheville to support the proposed school. In January 1897, Mrs. L. A. Farinholt began a media blitz asking for donations of “a stove, seats, desk or tables” and funds for the school in the factory district that the ladies were hoping to begin on February 2nd.[86] The school opened a day earlier than expected, on February 1, 1897, in a rented house at 31 W. Haywood Street,[87] under the supervision of Mrs. L. A. Farinholt, with Miss Queen Carson as the teacher. To help raise funds to keep the Factory School operating, “the society people of Asheville” organized a benefit play production, “Deestrick Skule” to be presented at the Grand Opera House on Patton Avenue in March of 1897.[88]

Finally, a year later, in October 1898, the Asheville City School Committee reported that in addition to awarding the Factory School $20 a month from the public-school funds, that “there is hope in the near future for a public school in the factory district”.[89] In June of 1899, the Asheville School Committee appointed Miss Queen Carson as principal of the factory school, as the “head of the contemplated school in that section”.[90] Fortunately, the “contemplated” school was opened in September 1899, under the auspices of the school committee, in a building, with a playground, “secured from the Asheville Cotton Mills”, just “west of the Melke place”,[91] which from other sources seemed to have been in one of the factory hill tenement houses. Miss Queen Carson was again appointed as the principal, along with two teachers, Miss Cora Carter, and Miss Grace Venable.[92]

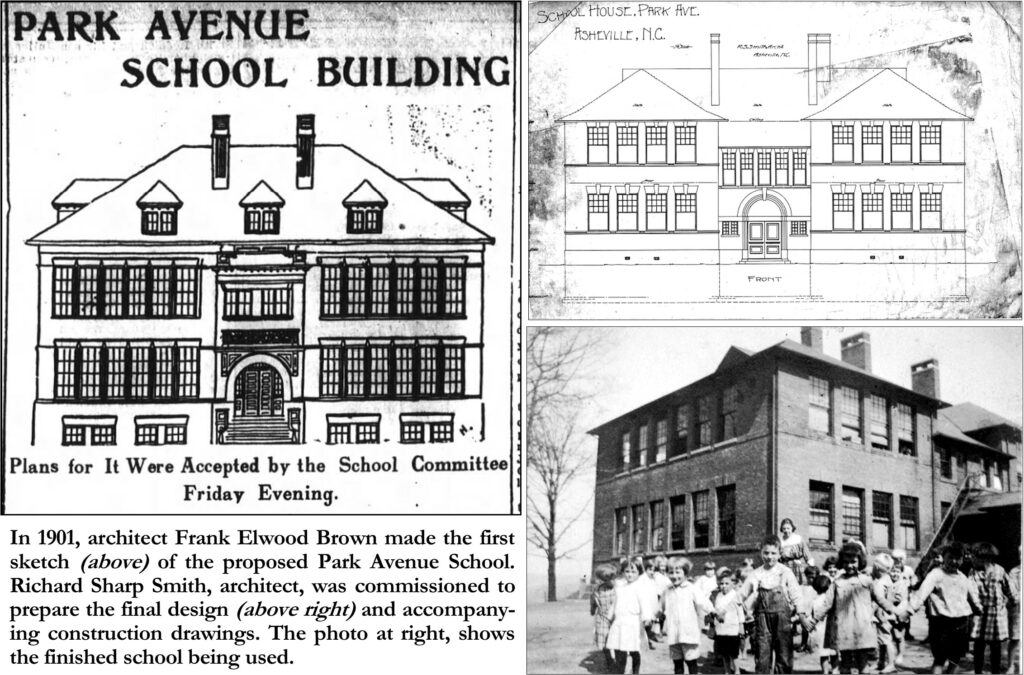

By 1901, the Factory School (also sometimes called the West End School) was thriving despite its inadequate facilities. In February of 1901, a special committee of the School Committee (Board), which was tasked to “examine the West End School building”, recommended “the erection of a new building on Park Avenue as soon as possible”.[93] To that end, a vote was submitted for the May Election, asking the voters to authorize the City to issue $10,000 in school bonds for the erection of a new school in the factory district. A positive vote was made at the May Election, and so by June the school committee had begun to solicit purchasers for the bonds[94], as well as began getting architectural plans for the new school.[95] The following month the School Committee, not only announced that they had hired architect, Frank Elwood Brown to design the new school, but they also published, along with the announcement, a rendering of the front elevation of the proposed design for the new school.[96] However, after a year of wrangling, in July of 1902, the School Committee announced that the contract to build the “Park Avenue School” had been awarded to the firm of McDonald & Spears, and that Richard Sharp Smith had been commissioned to draw the construction plans.[97] Apparently, Frank Elwood Brown’s design plans had only been used for marketing and fund-raising for the project.

The new brick two-story Park Avenue School, with classroom facility for 240 students, was completed by the June of 1903 opening.[98] The new school was built on a prominent lot on the north end of the east side of Park Avenue, next to the four large residences. Renamed Queen Carson Elementary School in the 1930’s, the school remained (with subsequent additions) as a beacon of learning for six decades until its closing in 1959. The school was demolished in 1960, and the site is now occupied by the workshops and garages of the Asheville Transit Services.

Prospect Park and Factory Hill (aka Chicken Hill) thrived on into the 1940’s, being occupied mostly by mill workers and railroad workers. In 1944, the Asheville Cotton Mills decided to sell their factory houses (on Factory Hill and in Park Square), offering them first to the current occupants, all of whom had been previously renting them from the Mill owners. However, despite a name change and a $225,000 renovation in 1949, the Mill closed in 1953. The 1950’s through the 1960’s, brought additional major disruption and devastation to these neighborhoods. The extension of Patton Avenue across the river to West Asheville began in 1948 with the building of the Smoky Park Bridge (now called the Jeff Bowen Bridge). The purchase of rights-of-way for the “Crosstown Expressway” (I-240) began in 1953, with actual construction beginning in 1958. Several houses and tenements on Factory Hill were taken for the new highway that then joined with the new Smoky Park Bridge.

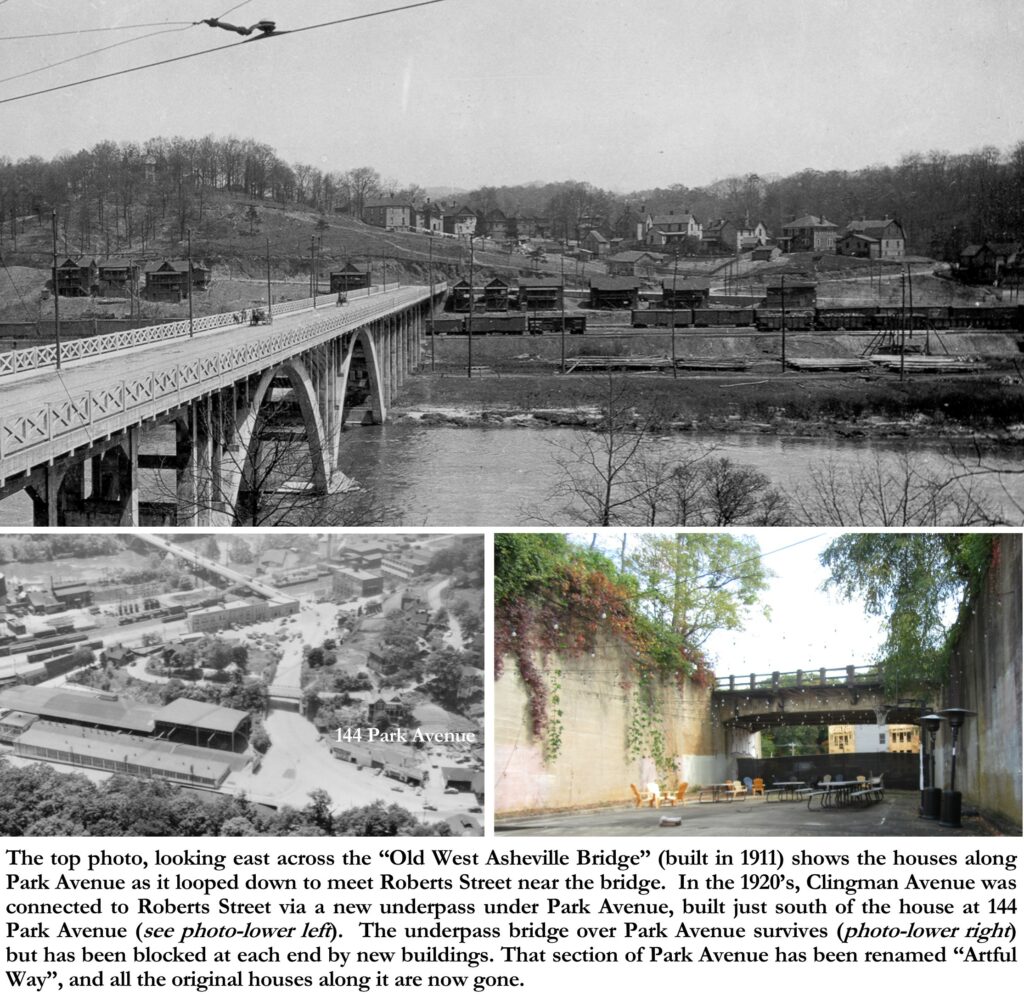

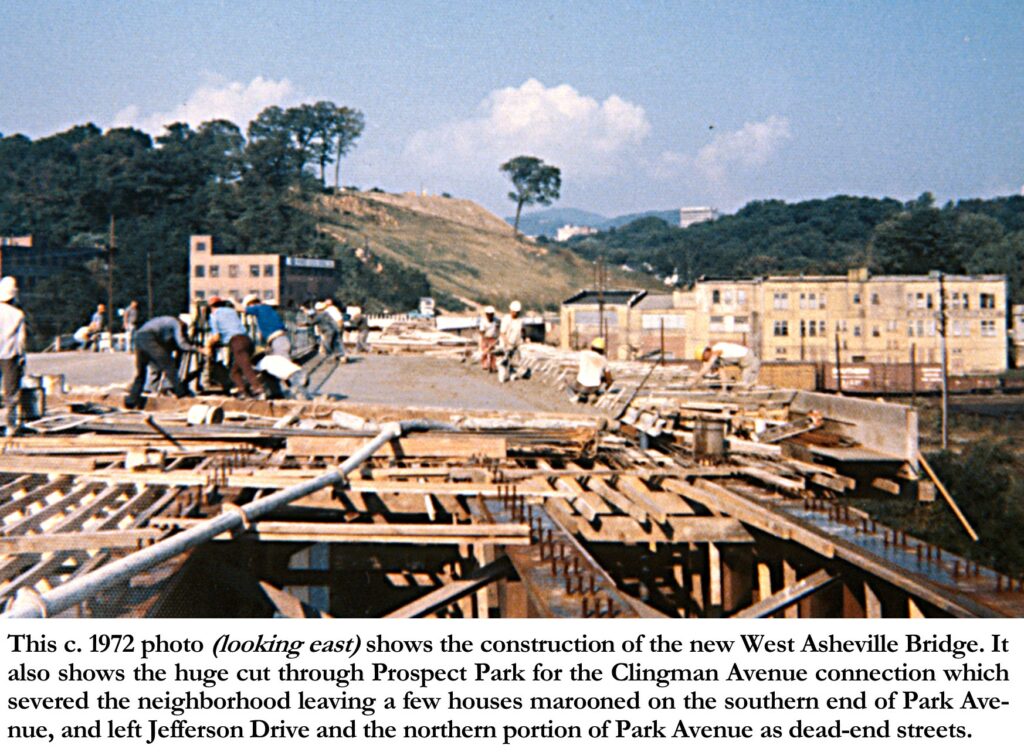

The Prospect Park neighborhood suffered a devastating blow in the early 1970’s. In 1910-11, the “old West Asheville Bridge” was built across the French Broad River, beginning near where Park Avenue looped down to meet Roberts Street on the east side of the river to join with Haywood Road on the west side of the river. By 1970, the old bridge was in a severe state of decay and deemed unsafe, and plans got underway to build a new replacement bridge. Construction began soon thereafter, with the new bridge opening in 1973.[99] But the devasting blow to Park Avenue was not the building of the bridge, but rather in building the east approach to the bridge. In the 1920’s, Clingman Avenue had been connected to the old West Asheville bridge via an underpass that was built under the southern portion of Park Avenue. This was a compromise from the originally proposed subway tunnel under Jefferson Avenue! However, the 1920’s underpass size and position was inadequate to handle the four-lane widening of Clingman Avenue needed in the 1970’s for the approach ramp to the new bridge. Unfortunately for the Prospect Park neighborhood, the solution was to create a huge cut through Prospect Park hill, which not only required the demolition of several houses, but it also severed the neighborhood leaving a few houses marooned on the southern end of Park Avenue, as well as leaving Jefferson Drive and the northern portion of Park Avenue as dead-end streets. This drastic scheme was perhaps recommended by the state of the hillside by 1970, where a large cut which had been taken in the 1920’s on the corner of Roberts and Clingman Avenue, had combined with a water line break which in turn resulted in a mudslide which had taken out a large section of the hillside, resulting in fatal damage to more historic homes on southwest side of Park Avenue in 1960.[100]

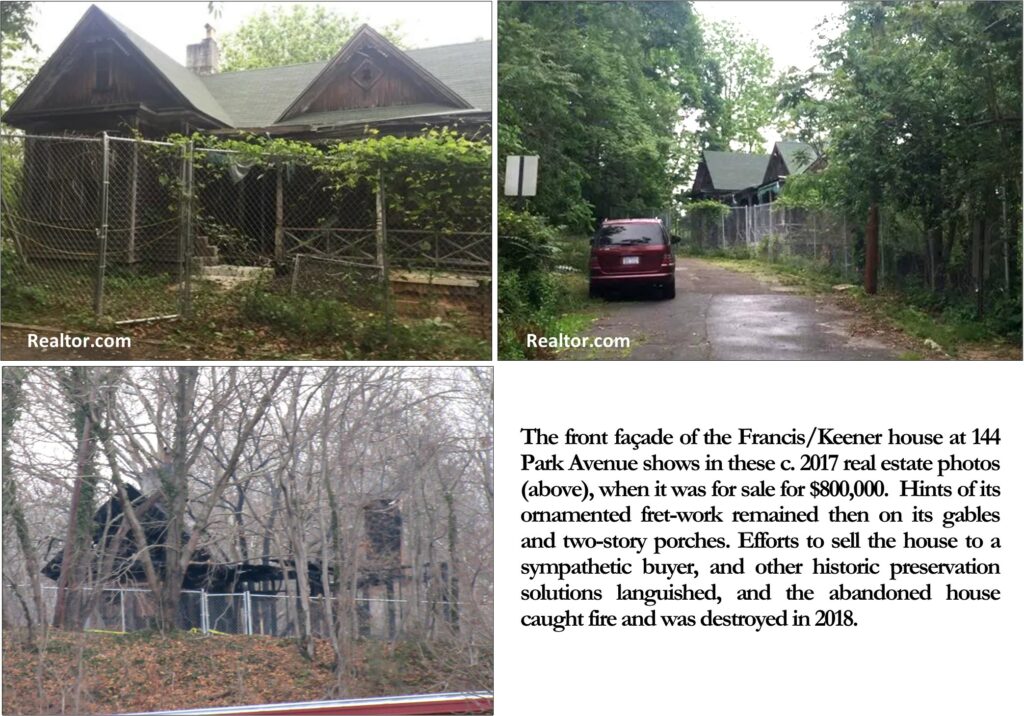

The house at 144 Park Avenue was a double victim to the road construction of the 1920’s, as well as that done in the 1970’s. In the 1920’s, Clingman Avenue was connected to Roberts Street via a new underpass under Park Avenue, built just south of the house at 144 Park Avenue. The house was further affected in the 1970’s when Clingman Avenue was rerouted just to the north of the house, leaving the house sitting on a precipice at the dead-end of Park Avenue. The historic house was built in 1896 by carpenter, W. C. (William Cotton) Francis, and his Wife, Mary S. Francis. Mary Francis ran the house as a boarding house until her untimely death in 1899. Upon Mary’s death, W. C. Francis moved in with his daughter’s family at 208 Park Avenue, and the house at 144 Park Avenue was leased to Jane Potts, who also used the residence as a boarding house. In the 1920’s-1950’s the house was owned and occupied by Orpheus and Bertha Keener, who ran a nearby grocery store. In 2017, the house became of interest to the Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County, having been identified as an “endangered property”. The house was considered “endangered” as its site, at the end of severed Park Avenue, made the house undesirable as a residence, and being surrounded by a planned development, the land was deemed more valuable than the house. Unfortunately, before a solution for preservation could be found, in 2018, the abandoned two-story home with its two floors of decoratively ornamented porches, was destroyed by fire, as a result of a homeless person lighting a fire under the house. The loss of the house at 144 Park Avenue was not only due to the lingering effects of the severing of Park Avenue during the 1970’s redevelopment, but it also was caused by historic preservation’s two major nemeses, neglect/abandonment, and fire!

This is a story of the development of Prospect Park and Factory Hill, but we would be amiss not to mention, albeit briefly, their more recent “redevelopment”. Beginning in 1995, the City of Asheville targeted these neighborhoods, which they singularly named the “West End/Clingman Avenue” neighborhood”, for revitalization and redevelopment. The “West End/Clingman Avenue Neighborhood Plan”, was prepared by the Asheville Planning and Zoning Department after seeking much input from the neighborhood’s “199 residents”.[101] Throughout the ensuing decade on into the 2000’s, the neighborhood was revitalized by private investors and community development groups such as Mountain Housing Opportunities. Although a few multi-family housing projects were built, such as the Prospect Terrace and Clingman Lofts condominiums, much of the revitalization took the form of building single family homes on in-fill lots, and the rehabilitation of existing historic homes.

Like many of Asheville’s historic neighborhoods, Prospect Park, Park Square and Factory Hill were developed during the late nineteenth century and flourished in the early to mid-twentieth century, but then declined into peril and neglect on into the twenty-first century. But today these neighborhoods, collectively known as the West End/Clingman neighborhood are thriving again, with their surviving historic houses proudly displayed next to and between their “new” neighbors.

Photo & Image Credits: All photos by Dale Slusser except the following: (Note: All cropping and captions by author)

C. E. Graham Portrait- closeup from ID- C170-8- c1922 Pelton photo (A7419) of Montreat officials and building crew in front of the recently completed Anderson (Rev. Dr. Robert Campbell Anderson) Auditorium. -Buncombe County Special Collections.

Asheville Cotton Mill- UNCA – Picturing Asheville and Western North Carolina, Asheville Cotton Mill, 1920 Herbert Pelton photo. #Ball1961, Southern Appalachian Digital Collections. https://southernappalachiandigitalcollections.org

Closeup from the 1886 Map of Asheville- MAP 200– 1886 Map of Asheville, Buncombe County Special Collections.

Prospect Park Plat- 01/01/1890 PROSPECT PARK- PLAT DEPOT ROBERTS & HAYW OOD STREETS Db. 8/12. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Prospect Park Advertisement– Asheville Citizen-Times, July 1, 1887, page 4. -newspapers.com

Sale advertisement for Rhinehart house– Asheville Citizen-Times, December 8, 1889, page 3. -newspapers.com

For Sale- Geo. Walker House- Asheville Citizen-Times, July 16, 1890, page 2. -newspapers.com

Closeup of Prospect Park-1891 Bird’s-Eye View- Ruger & Stoner, and Burleigh Litho. bird’s-eye view of the city of Asheville, North Carolina. [Madison, Wis, 1891] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694894/

T. H. Lindsey Stereo View- Image ID-A253-8- “West Asheville” #143, Asheville & Vicinity, Class A, Views of Western N.C., T. H. Lindsey- Buncombe County Special Collections.

Photo of Julia Woodcock House- Image ID-A528-4- An “unidentified” house on Park Ave, with a man is standing in front by a fence. The house is large and has a tall ornate central tower. Dated ca 1906. – Buncombe County Special Collections.

Peter Demens Portrait- Wikimedia- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Demens_1.jpg

- Banks Holt of Alamance- “Sky-land”, by Mae Lucile Smith (Published: Winston-Salem, 1913) page 254. –archive.org

- D. Long & Family- Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, Archives and Manuscripts Collections, The Baltimore Museum of Art. CP27.3.8and Nancy Hirschland

Etta Cone with Long children at Park Avenue House- Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, Archives and Manuscripts Collections, The Baltimore Museum of Art. CP27.3.5

Etta Cone with Dorothy Long at Park Avenue House- from the Ellen B. Hirschland Collection- scanned from: The Cone Sisters of Baltimore: Collecting At Full Tilt, by Ellen B. Hirschland Ramage. (Evanston, IL : Northwestern University Press), page 29.

Closeup of Factory Hill on Sanborn Map- Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Asheville, Buncombe County, North Carolina. Sanborn Map Company, Jun, 1907. Map, Sheet 21. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn06372_006/.

Richmond Pearson Plat- 01/01/1905 Richmond Pearson – PLAT ON FRENCH BROAD RIVER Db. 8/70. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

“Park Avenue School Building”- Frank Elwood Brown sketch- The Asheville Citizen-Weekly, July 2, 1901, page 4. -newspapers.com

Park Avenue School Building- ID-H239-4 – Park Avenue School, #30 Park Ave, opened ca 1901-2. – Buncombe County Special Collections.

Closeup 1948 Photo of Smoky Park Bridge Construction– ID-B116-XX- Aerial view from the SW showing construction of I-240 and the Smoky Park Highway Bridge. – Buncombe County Special Collections.

Looking East from Old West Asheville Bridge Photo- ID-A038-8 – Clingman Ave (“Old” West Asheville) Bridge (1911-1972), as seen from the west. – Buncombe County Special Collections.

Photo of Park Avenue Underpass at Clingman Avenue- ID-D152-5 -Bingham aerial view from packet A-74: “Dave Steel, Asheville NC.5/31/47..1:00PM”. At the intersection of Lyman St, Clingman Ave, and Roberts St by the Southern Railway tracks. -Buncombe Special Collections.

Photo of building the new West Asheville Bridge- ID-N958-S – Slide donated of the Clingman Ave (“New” West Asheville) Bridge (1972), facing East, during construction. -Buncombe Special Collections.

Two photos of 144 Park Avenue for Sale- 2017 photos from realtor.com

[1] “Prospect Park Prospects”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 28, 1889, page 1. -newspapers.com

[2] Asheville Weekly Citizen, May 22, 1879, page 1. -newspapers.com

[3] See: Asheville Weekly Citizen, September 25, 1884, page 3.; and Asheville Citizen-Times, October 27, 1885, page 1. -newspapers.com

[4] “French Broad Bank”, Asheville Citizen-Times, January 14, 1887, page 1. -newspapers.com

[5] Ibid.

[6] “CHANGE IN BUSINESS”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 16, 1886, page 2. -newspapers.com

[7] The News & Observer, Raleigh, NC, May 25, 1886, page 3. -newspapers.com

[8] “CHANGE IN BUSINESS”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 16, 1886, page 2. -newspapers.com

[9] Ibid.

[10] Asheville Citizen-Times, January 14, 1887, page 1. -newspapers.com

[11] Asheville Citizen-Times, January 14, 1887, page 1. -newspapers.com

[12] Asheville Citizen-Times, April 15, 1887, page 1. -newspapers.com

[13] “NEW COTTON FACTORY”, Asheville Citizen-Times, April 14, 1887, page 1. -newspapers.com

[14] “West Asheville And Some of Its Enterprises”, The Daily Sun, Asheville, NC, June 13, 1888, page 1.; AND The New Era, Shelby, NC, February 1, 1888, page 3. -newspapers.com

[15] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 22, 1887, page 1. -newspapers.com

[16] The Raleigh News, Raleigh, NC, January 3, 1877, page 1. -newspapers.com

[17] The Asheville Weekly Citizen, January 10, 1878, page 3. -newspapers.com

[18] “WILLIAM W. WEST DIES”, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, PA, February 13, 1923, page 2. -newspapers.com

[19] 08/10/1885 G. M. Whitson, Commiss.-C. T. Burnett and others ex-parte to W. B. Gwyn and C. E. Graham 110 ACRES FRENCH BROAD RIVER Db. 47/457. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[20] 03/01/1866 N. W. Woodfin, Attny-Estate of James W. Patton to J. M. L. Burnett 69 ACRES FRENCH BROAD RIVER Db. 28/47. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[21] 09/11/1885 C. E. & Susie J. Graham; W. B. & Helen Gwyn to Asheville Cemetery Company 35 ACRES Db. 47/583. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[22] Asheville Citizen-Times, July 1, 1887, page 4. -newspapers.com

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] 01/01/1890 PROSPECT PARK- PLAT DEPOT ROBERTS & HAYWOOD STREETS Db. 8/12. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[26] “PROPSECT PARK”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 9, 1887, page 1. -newspapers.com

[27] Ibid.

[28] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 14, 1888, page 1. -newspapers.com

[29] Asheville Citizen-Times, December 8, 1889, page 3. -newspapers.com

[30] “Prospect Park Prospects”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 28, 1889, page 1. -newspapers.com

[31] Asheville Citizen-Times, July 16, 1890, page 2. -newspapers.com

[32] “Prospect Park Prospects”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 28, 1889, page 1. -newspapers.com

[33] 12/09/1889W. B. & Helen Gwyn to R. E. Bowles JEFFERSON STREET Db. 68/285. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[34] 08/27/1885 D. D. & Julia W. Adams to R. E. Bowles HAYWOOD STREET Db. 48/544. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[35] “The Battery Park Hotel Force”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 17, 1886, page 1. -newspapers.com

[36] “Died”, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 27, 1888, page 1. -newspapers.com

[37] “North Carolina Marriages”, The Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, NC, October 27, 1888, page 2. -newspapers.com

[38] 04/03/1888 W. B. & Helen Gwyn to C. M. Hampton JEFFERSON STREET Db. 62/109. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[39] 01/17/1890 (rec’d-06/03/1890) C. M. Hampton to D. D. Adams JEFFERSON STREET Db.70/622. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[40] 12/31/1889 (rec’d 01/11/1890) C. E. & Susan Graham to Sarah Cole Smith PARK AVENUE Db. 68/563. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[41] Asheville Citizen-Times, May 20, 1890, page 1. -newsapapers.com

[42] 05/27/1887 T. I. & E. A. Van Gilder; T. E. Brown; E. W. Brown; L. V. Brown to Julia Emma Woodcock PARK AVENUE Db. 59/60. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[43] The Asheville Times, August 23, 1969, page 12. -newsappers.com

[44] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 16, 1891, page 4. -newspapers.com

[45] Ibid.

[46] 09/17/1895 (rec’d-11/18/1895) Wake Forest College to Asheville Cotton Mills BUXTON STREET Db. 94/342. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[47] “HAYWOOD BAPTIST CHURCH TO OBSERVE MEMORIAL HOMECOMING”, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 23, 1968, page 3. -newspapers.com

[48] “MR. DEMEN’S SCHEME”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 26, 1889, page 1. -newspapers.com

[49] Ibid.

[50] “THE BIG FACTORY”, Asheville Citizen-Times, August 3, 1889, page 1. -newspapers.com

[51] See: “H. W. Fitch” The Alias Architect and Builder of Buncombe County, by Dale Wayne Slusser on the Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County website: https://psabc.org/h-w-fitch-the-alias-architect-and-builder-of-buncombe-county/

[52] 06/24/1890 C. E. & Susan Graham to Peter A. & Raisse L. Demens PROSPECT PARK AVENUE & GIRDWOOD STREET Db. 71/326. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[53] Biography of Peter A. Demens, by Michael Southern, on The North Carolina Architects and Builders: A Biographical Dictionary. https://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000068

[54] 03/03/1893 P. A. Demens to James H. & C. T. Rumbough GIRDWOOD STREET Db. 81/96. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds. See also: The Asheville Weekly Citizen, March 10, 1892, page 2. -newspapers.com

[55] “ANOTHER AUCTION SALE”, Asheville Citizen-Times, June 12, 1890, page 4. -newspapers.com

[56] “Prospect Park”, Asheville Citizen-Times, June 24, 1890, page 4. -newspapers.com.

[57] 02/16/1891 C. E. & Susan Graham to P. F. Patton GIRDWOOD STREET Db. 75/251. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[58] “Sold Out His Interest”, The Twin-City Daily Sentinel, Winston, NC, July 27, 1892, page 1. -newspapers.com

[59] “BIG PURCHASE”, Asheville Weekly Citizen, January 14, 1892, page 2. -newspapers.com

[60] 04/15/1893 Graham Manufacturing Company [INC] Db. C001/264. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[61] Asheville Weekly Citizen, May 4, 1893, page 5. -newspapers.com

[62] “Mr. M. D. Long of Baltimore”, Asheville Citizen-Times, August 18, 1888, page 1. -newspapers.com

[63] 07/05/1889 (rec’d-07/27/1889) J. W. & M. B. Wadsworth to Moses H. Cone PARK AVENUE Db. 67/24. -Buncombe Register of Deeds.

[64] 07/03/1897 Moses & Bertha Cone to Carrie Cone Long PARK AVENUE Db. 102/88. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[65] 10/13/1928 Atlantic Bank & Trust, TR; Carrie Long Estate to George Y. Mebane EAST SIDE PARK AVE Db. 401/226. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[66] 06/29/1971 Carl W. & Elizabeth Pressley to Pioneer Welding Supply DB 898 PG 564 Db. 1041/84. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[67] Asheville Citizen Times, March 17, 1896, page 4. -newspapers.com

[68] “ASHEVILLE’S MILL COLONY”, Asheville Citizen-Times, September 4, 1901, page 4. -newspapers.com

[69] Ibid.

[70] 08/04/1892 Richmond & Gabrielle Pearson to C. E. Graham Manufacturing Co. VIEW STREET Db. 83/74. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[71] 01/01/1905 Richmond Pearson PLAT ON FRENCH BROAD RIVER Db. 8/70. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[72] “FRENCH BROAD AWAY UP. NINE FEET ABOVE THE LOW WATER MARK”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 23, 1891, page 1. -newspapers.com

[73] Cabins and Castles: The History & Architecture of Buncombe County, North Carolina, Edited by Douglas Swaim. (Asheville, NC: Historic Resources Commission of Asheville and Buncombe County, 1981) page 166.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 28, 1900, page 8.; See also: Asheville Times, June 23, 1900, page 3. -newspapers.com -newspapers.com

[76] 02/21/1901 J. W. Cash to Dora B. Phillips JEFFERSON STREET Db. 116/207. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[77] 07/23/1907 John H. & Amanda E. Cheek to Dora B. Phillips JEFFERSON DRIVE Db. 151/339; Also: 07/23/1907 C. Burt to Dora B. Phillips JEFFERSON DRIVE Db. 151/340. -Buncombe Register of Deeds.

[78] Will of Dora B. Phillips, January 14, 1917, Will Records, (Buncombe County, North Carolina), 1831-1964; Index, 1831-1964; Author: North Carolina. Superior Court (Buncombe County); Probate Place: Buncombe, North Carolina. -ancestry.com1

[79] 11/21/1921 S. H. Phillips/Commiss. To O. W. Cooper JEFFERSON DRIVE Db. 247/518. “Whereas by an order and judgement of the Superior Court, entered at November Term 1921, in a civil action titled Thelma Phillips against Clinton B. Phillips, et. al., said S. H. Phillips was appointed a Commissioner of the Court and was ordered and directed as such commissioner to sell and convey the lot of land hereinafter to be described, to the party of the second part…Forty Five Hundred ($4,500) dollars…being the property on which stands a house known as No. 31 Jefferson Drive…”. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[80] “Means-Phillips”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 4, 1922, page 14. -newspapers.com

[81] “TO PROBE DEATH OF B. C. MEANS- Died Supposedly of Broken Neck Received In Fall”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 5, 1925, page 1. -newspapers.com

[82] 02/28/1931 O. C. & Thelma Bryson to Clinton B. Phillips WEST MARGIN JEFFERSON ST Db. 434/68. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[83] 03/16/1933 Clinton B. Phillips to R. T. Cecil WEST MGN JEFFERSON DR Db. 451/303. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[84] “FLOWER MISSION APPROPRIATION”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 28, 1896, page 1. -neswpapers.com

[85] Asheville Citizen-Times, December 5, 1896, page 4. -neswpapers.com

[86] Asheville Citizen-Times, January 14, 1897, page 4. -newspapers.com

[87] Asheville Citizen-Times, January 30, 1897, page 1. -newspapers.com

[88] Asheville Citizen-Times, March 11, 1897, page 2. -newspapers.com

[89] Asheville Citizen-Times, October 8, 1898, page 5. -newspapers.com

[90] “SCHOOL COMMITTEE MEETS”, Asheville Citizen-Times, June 5, 1899, page 1. -newspapers.com

[91] “FACTORY SCHOOL- Building Put In Order For the Year’s Work”, Asheville Citizen-Times, September 12, 1899, page 1. -newspapers.com

[92] Ibid.

[93] Asheville Citizen-Times, February 7, 1901, page 8. -newspapers.com

[94] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 18, 1901, page 4. -newspapers.com

[95] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 10, 1901, page 1. -newspapers.com

[96] “MEETING OF THE SCHOOL COMMITTEE”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 2, 1901, page 4. -newspapers.com

[97] “CONTRACT FOR THE NEW SCHOOL IS LET”,

Asheville Citizen-Times, July 25, 1902, page 1. -newspapers.com

[98] “PARK SCHOOL RECEPTION”, Asheville Weekly Citizen, June 2, 1903, page 8. -newspapers.com

[99] “W. Asheville Bridge May Open Friday”, Asheville Citizen-Times, December 19, 1973, page 13. -newspapers.com

[100] “Rain Caves In 50-ft Section Of Park Avenue”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 6, 1960, page 1. -newspapers.com

[101] “West End-Clingman residents ask City to aid revitalization”, Asheville Citizen-Times, August 16, 1996, page 11.