by Dale Wayne Slusser

George Washington Vanderbilt began building his 250-room French Renaissance château in the mountains of Western North Carolina, just south of Asheville in 1889. Designed by the renowned architect, Richard Morris Hunt, construction of “Biltmore” was completed by its grand opening during the Christmas of 1895. Along with the grand house, Vanderbilt also amassed a grand estate of 125,000 acres, which included 75 acres of formal and informal gardens surrounding the house, designed by renowned American landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, and a vast forest to the southwest surrounding Mount Pisgah. Vanderbilt’s accumulation of land was not an act of a greedy rich millionaire, but in fact, Vanderbilt was a pioneer in the emerging agriscience of sustainable land use practices, eventually using his land to establish a farm-to-table “market garden” farm, a nursery to propagate and sell native plants, an arboretum, a dairy, and perhaps his greatest experiment, a sustainable forest.[1]

Every grand estate in Britain, and so in America, needed an accompanying “village” to house the servants and “estate workers” and parish church. “Biltmore Village” was started immediately after the completion of the Biltmore House, just located outside the estate entrance at the “Best” depot, named for William Best, a principal owner of the Western Carolina Railroad Company which had brought rail service to the area in 1880. To add to his grand estate and village, Squire Vanderbilt married Edith Stuyvesant Dresser in 1898, who bore their only child and heir, Cornelia Vanderbilt in 1900. However, all this grand extravagance and costly land experiments and estate building barely lasted for fifteen years, before it was clear that economic measures would have to be undertaken to maintain the estate.

In the modern British documentary television series titled “Country House Rescue,”[2] owners of historic Country Houses and Estates in Britain, who are struggling financially, seek out the advice of experts on how the owners of these stately homes can protect the future of their historic buildings and estates. Most of these estates were built by wealthy ancestors in an age when they could be sustained through a sophisticated network of servants, tenants, and estate managers. But over the years they have been inherited by mostly cash poor descendants who have not the money nor the staff to adequately maintain an estate. Such was the state of Biltmore Estate in 1920, with its owner and builder George W. Vanderbilt having passed away in 1914, and its financial resources dwindling, something had to be done to secure its future. Like the British estates, one huge resource that the Biltmore Estate DID have was LAND!

As early as 1908, George Vanderbilt recognized that land was his primary resource. The Panic of 1907 was the impetus for Vanderbilt’s first attempt to sell some of his land. The Biltmore Forest School, which had been established in 1898 to train future foresters and land managers, though being a success in its mission, was by 1908 a financial failure and burden to Vanderbilt. In 1908, George Vanderbilt instructed Carl Schenck, director of the Biltmore Forestry School, “to try to sell as much of Pisgah Forest as possible…”[3] and that in return Schenck, if he was successful in getting a buyer, would be paid “the standard agent’s commission.”[4] Instead of doing as requested, in 1909, Schenck negotiated a 10-year lease granting hunting and fishing rights on the 80,000 acres of Pisgah Forest land, to a group of men associating as the “Biltmore Rod & Gun Club,” for $5,000 a year. George Vanderbilt, who was away from the estate when Schenck negotiated the lease, was furious with Schenck when he found out that he had not been consulted and felt that Schenck was not in a position to have made that decision on his own. Vanderbilt quickly repudiated the lease and by the following year, Schenck was dismissed.[5]

The Weeks Act was passed by Congress on March 1, 1911, authorizing the federal purchase of eastern lands for conservation purposes. It permitted the federal government to purchase private land to protect the headwaters of rivers and watersheds in the eastern United States and called for fire protection efforts through federal, state, and private cooperation.[6] In 1913, George Vanderbilt offered to sell the 80,000 acres of the Pisgah Forest to the Federal Government, but the Federal Government declined the offer. But then in 1914, things took a dramatic turn! On March 6, 1914, George Washington Vanderbilt suddenly died from an undetected blood clot, a few days after what was thought to have been a successful appendectomy. He died at the Vanderbilt’s house in Washington, DC, where they had moved to in 1908 for Cornelia’s schooling. In his will, George Vanderbilt left the Biltmore Estate to his thirteen-year old daughter Cornelia, along with $5,000,000 to be held in trust by his executors until “she becomes twenty-five years of age.”[7] The widow, Edith Vanderbilt was left the house in Washington, DC, the house in Bar Harbor, Maine, and the 80,000-acre Pisgah Forest in North Carolina. Edith Vanderbilt and George’s brother William K. Vanderbilt were appointed the executors/trustees of the estate.

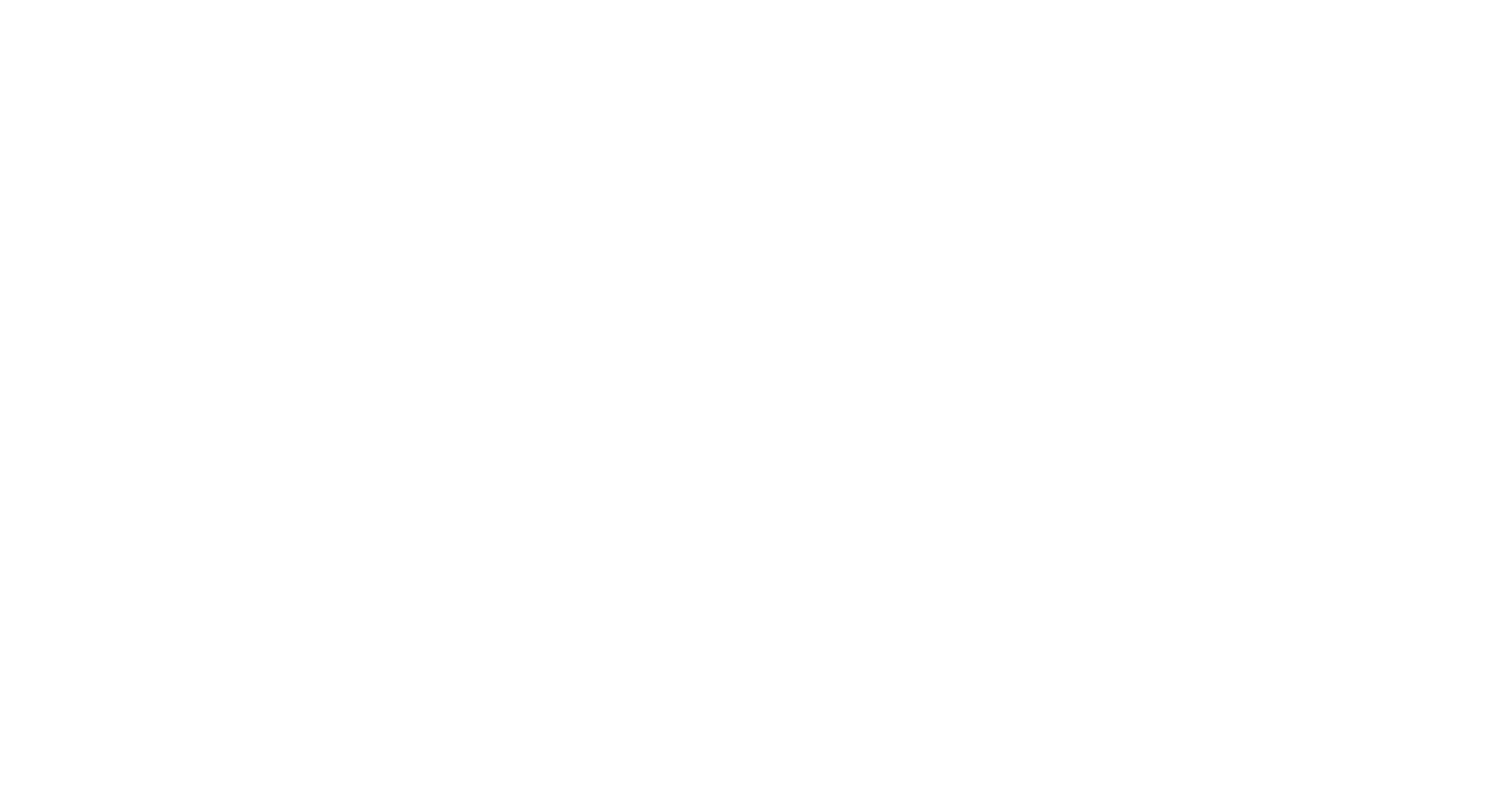

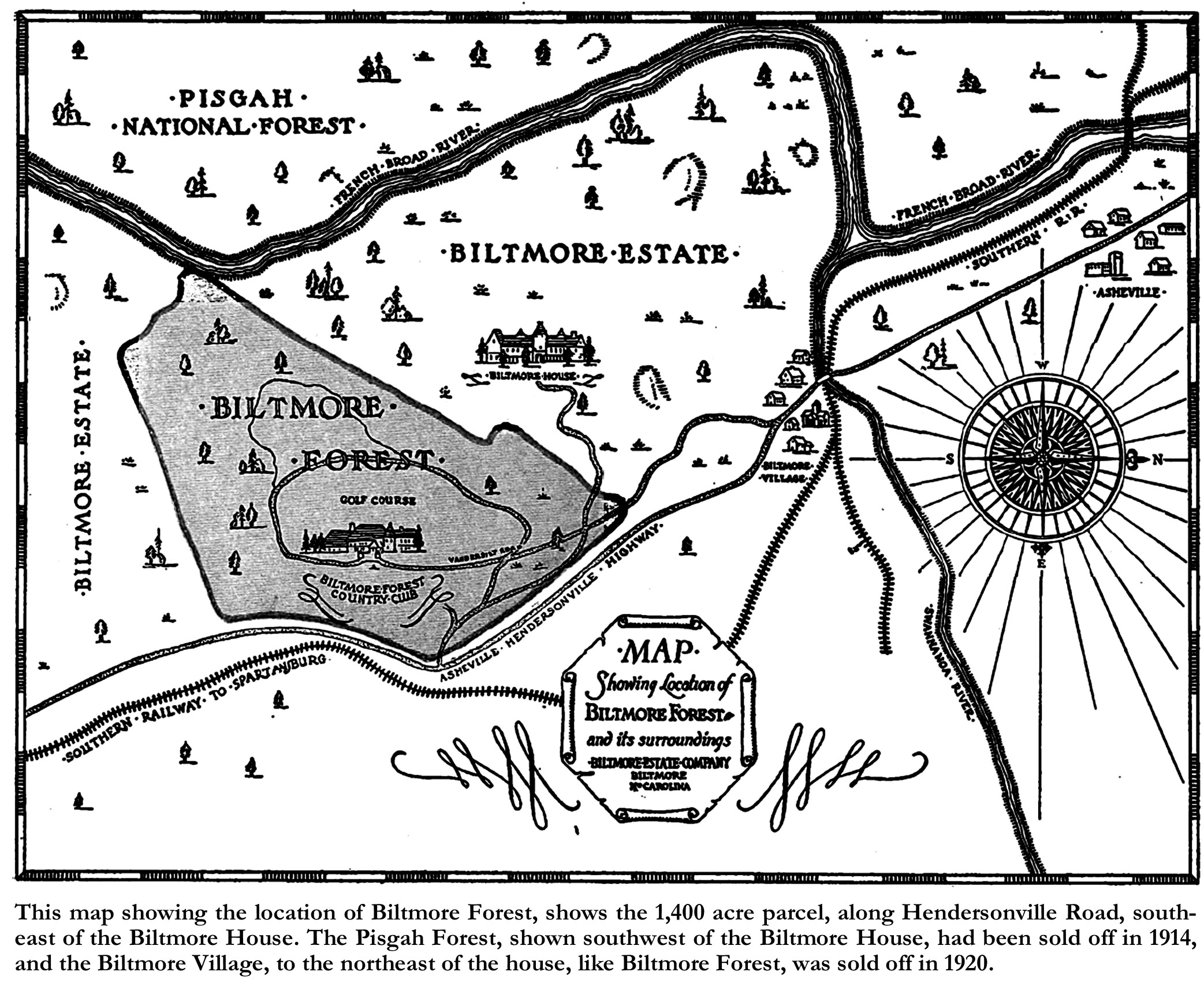

Following George’s death, the fate of Biltmore Estate, Biltmore Village and the Pisgah Forest were now the responsibility of Edith Vanderbilt. “For all his riches,” writes biographer Denise Kiernan, “George Vanderbilt was in many ways leaving behind an architectural albatross, one that would require a good deal of care and savvy financial maneuvering if it were to survive in one piece.”[8] But Edith was up for the task, getting to work immediately. On May 1, 1914, in a letter addressed to the Secretary of Agriculture, Edith submitted a generous reduced offer to the U. S. Government to purchase 86,700 acres of the Pisgah Forest as a national park. The offer was so generous, at $5.00 per acre, that within the month her offer was accepted, and she was successful in selling the Pisgah Forest lands for $433,851.[9] Although this was a significant chunk of the Biltmore Estate, it still left 10,000 acres, including the Biltmore House and Village.

Another societal factor that threatened the success of Biltmore at that time, which is often overlooked, was the passing of the 16th Amendment to the U. S. Constitution, ratified in 1913. “The amendment stated, “Congress shall have the power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several states, and without regard to any census or enumeration.” Later, Congress adopted a 1 percent tax on net personal income of more than $3,000 with a surtax of 6 percent on incomes of more than $500,000.”[10] This new tax was at first only for the wealthy, however, since the Biltmore House and Village were bankrolled by the Vanderbilt income, this meant that a loss of personal income (to the government) was also a loss to the financial stability and sustainability of the Biltmore Estate.

One of the final blows to the financial stability of Biltmore was the devastating flood of 1916. The rising waters of both the French Broad and Swannanoa Rivers not only deluged the Biltmore Village creating havoc, but they also destroyed the Biltmore Nursery and greenhouses and also, the Market/Truck Farm businesses, which had straddled both sides of the Swannanoa. The Biltmore Nursery was one of the few Biltmore Estate ventures that was making a profit.

By 1920, Biltmore Estate was struggling to survive. The economic woes of World War I, from 1917 to 1919, and the resultant loss of manpower further crippled the sustainability of the estate. In 1920, the trustees of Biltmore (Edith Vanderbilt and her brother-in-law, William K. Vanderbilt), upon the advice of their long-time lawyer, Judge Junius G. Adams, who had been called in as an advisor following the death of George Vanderbilt, decided to pursue two strategic initiatives. The first was to sell the entire Biltmore Village, excepting All Souls Church and the Biltmore Hospital, to a Charlotte, NC developer, George Stevens. This not only gave the estate some much needed cash, but also relieved them of the ongoing burden and expense of maintaining all the village buildings and its infrastructure.

The second initiative, which was more dramatic and extensive, was to sell off part of the Biltmore Estate to be developed into a “high-end” residential development. “Biltmore Estate Company Acquires Tract Two Miles Long on Hendersonville Road, for the Greatest Development In History of Western North Carolina,” heralded the Asheville Citizen-Times, on June 20, 1920.[11] This exciting news was soon broadcasted across the states of North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia. It was further reported that “those composing the Biltmore Estate Company” were “the Vanderbilt estate, with whom will be associated T. W. Raoul, former President of the Albemarle Park company; Burnham S. Colburn, capitalist of Detroit and Asheville; William A. Knight, capitalist of St. Augustine and Asheville; and Judge J. G. Adams of this city.”[12] The reporter was mis-informed, as the “Biltmore Estate Company,” a newly incorporated company, did not include the “Vanderbilt estate,” but only the four mentioned businessmen.[13] The Vanderbilt estate, merely sold the land to the new company. However, they benefited not only from the cash generated by selling the 1,400 acres, but also, they were relieved again of the ongoing burden and expense of maintaining what was mostly unused land on the estate. Also, Edith Vanderbilt was supportive of the new adventure, and would eventually build her own house, called “The Frith” on a large tract in Biltmore Forest.

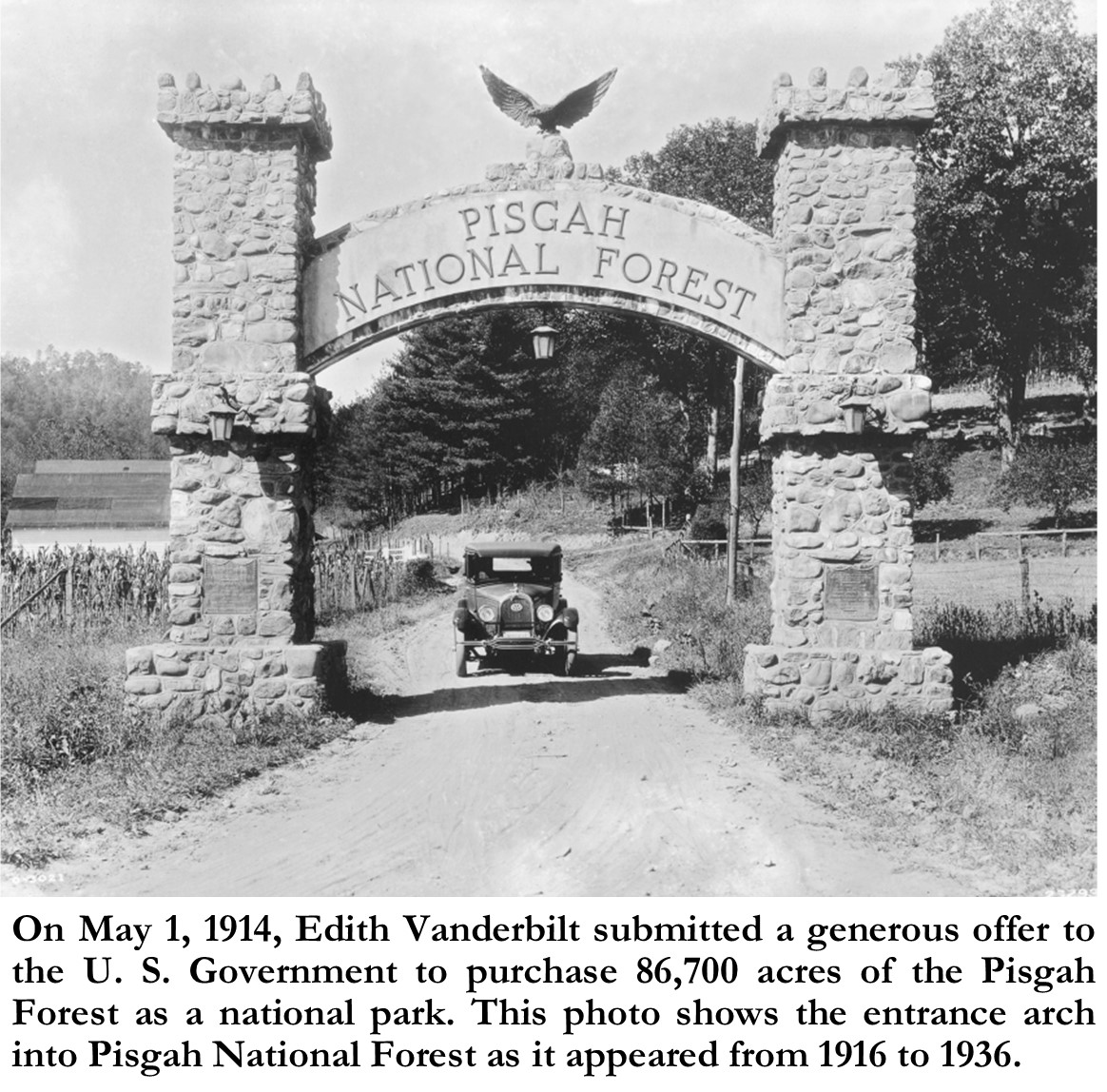

But this would be no ordinary 1920’s development! Originally named, “Biltmore Estate Park,” the name of he grand development, was soon changed to “Biltmore Forest,” which kept its connections to Biltmore Estate, but also reflected the development’s idyll of being an enclave of mini grand country estates. “There will be no lots for sale,”[14] it was announced, instead the new developments would be laid out in “tracts,” the smallest being between 3 to 5 acres, and on up, with at least three tracts being of 100 acres each. The developers unabashedly advertised that, “The idea is to throw restrictions around the property so that wealthy people from all sections of the country will be attracted here, where they can purchase land and develop their own estates.”[15] The two main thoroughfares, which were more like long country roads, were called Vanderbilt Road and Stuyvesant Road, reflecting George and Edith’s family roots, and the other streets (roads) were named with “woodsy” names such as: Forest, Southwood, Eastwood, Greenwood, and Cedarcliff. Plans also included an 18-hole golf course, designed by Donald Ross with an accompanying Country Club. A grand hotel was also planned, to be located just off Hendersonville and Busbee Roads on the eastern edge of the development. The hotel was never built. Just five years after the start of this unique development, D. Hiden Ramsey, a local educator, described it thusly, “Biltmore Forest is not a city. Neither is it a suburb. It is a sanctuary for the retired business man and the active leaders of the professions and of industry who wish to escape in their homes from the tumult, unsightliness and neurotic life of the modern city.”[16]

Although Thomas W. Raoul, was not the majority stockholder of the Biltmore Estate Company, according to a contemporary report he was “the leading spirit”[17] in the new company. This is not surprising as Raoul had just sold Albemarle Park development to E. W. Grove, in order to have the time and investment to give to the new Biltmore Forest development. In 1896, Thomas Wadley Raoul was a young twenty-year old, working in the offices of S. M. Inman Cotton merchants in Macon, GA, when he was suddenly “mowed down” with tuberculosis. As he later recounted, “At this point Father took over.” Thomas was first sent off to the West, “to breathe its health-giving air,” but to no avail. He soon found himself shipped off to Asheville to regain his health, where his Father, as part of Thomas’s cure, put him to work cutting out and clearing “the Asheville Place” with a view to the possibility of cutting it into building lots and selling it. The “Asheville Place” was the Deaver farm on North Charlotte Street which Thomas’s father, William Greene Raoul, a railroad executive, had purchased in 1886 as a summer home for the family. But following a suggestion by hotelier Col. Frank Coxe of the Battery Park Hotel, that they should build a boarding house, the Raouls decided to keep the property intact, build a boarding house/hotel and accompanying cottages to cater to the “summer people” who flocked to Asheville during the summer season. William G. Raoul enlisted architect Bradford Gilbert to design the new hotel, which would be named “The Manor,” and Raoul also enlisted landscape designer Samuel Parsons to lay out the grounds surrounding the hotel into sites for accompanying cottages.

The Raoul family lived in Atlanta and summered in Asheville, however, because of Thomas’s tuberculosis, it was decided that Thomas should make Asheville his permanent home. So, Thomas Raoul became the fulltime project manager of his father’s development which was named Albemarle Park. And following William G. Raoul’s death in 1913, Thomas not only continued to manage Albemarle Park, but he also began a major redevelopment of the property, adding an addition to “The Manor” hotel and subdividing lots and building new cottages. And so, Thomas Wadley Raoul was the logical officer of the Biltmore Estate Company to head up the development of Biltmore Forest, not only because he was a fulltime resident of Asheville (and could be always onsite), but also because he had just finished almost two decades gaining experience in building and property development.

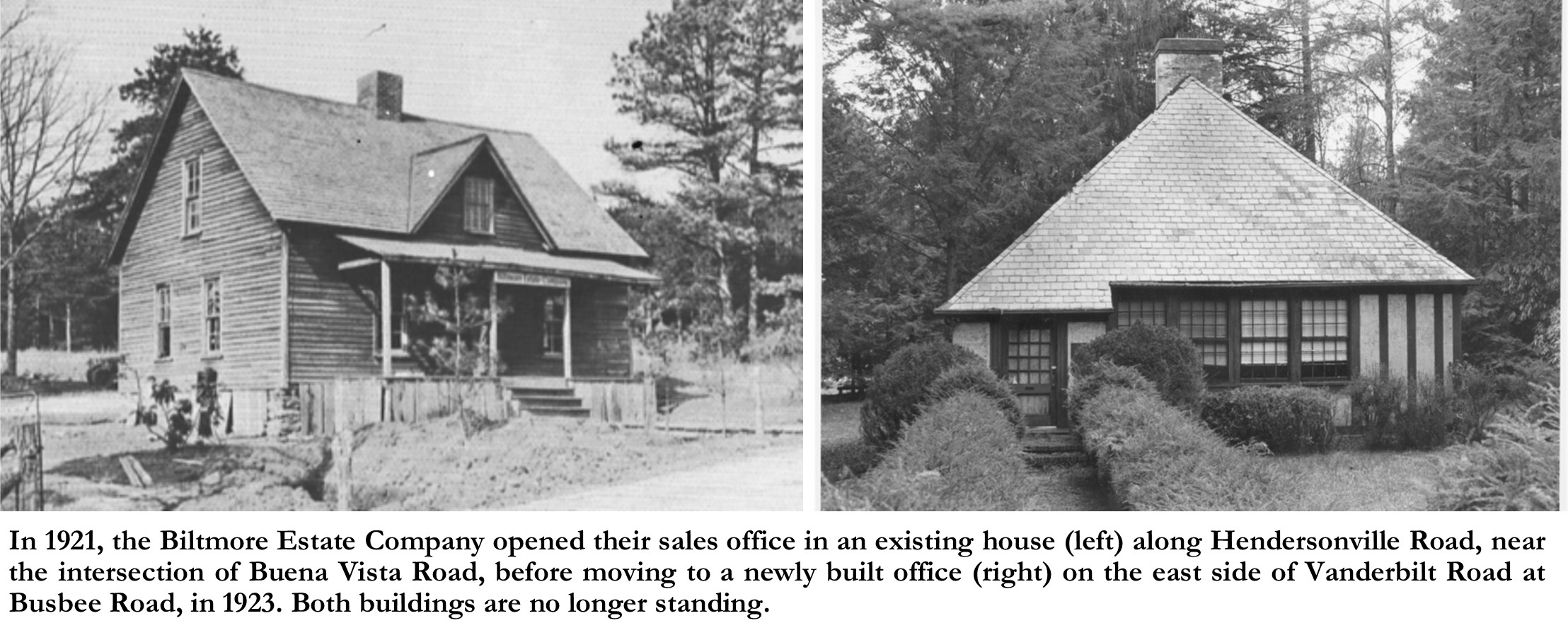

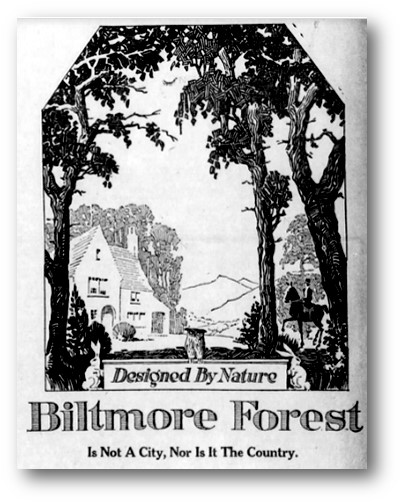

Raoul became the head salesman for the new Biltmore Forest development, beginning in 1921, first setting up a sales office in an existing house along Hendersonville Road, near the intersection of Buena Vista Road, before moving to a newly built office on the east side of Vanderbilt Road at Busbee Road, in 1923. In 1921, as the new office opened, the Biltmore Estate Company started its creative and enticing advertising. The ads which included a pen and ink sketch of an English country house set amongst a woodland setting with the mountains as its backdrop, featured a center plaque, bookended on each side by a bunny and topped by a roosting great-horned owl, which claimed, “Designed by Nature.” Below the plaque in capital letters, the ad read: “BILTMORE FOREST, Is Not a City, Nor Is It the Country.”[18]

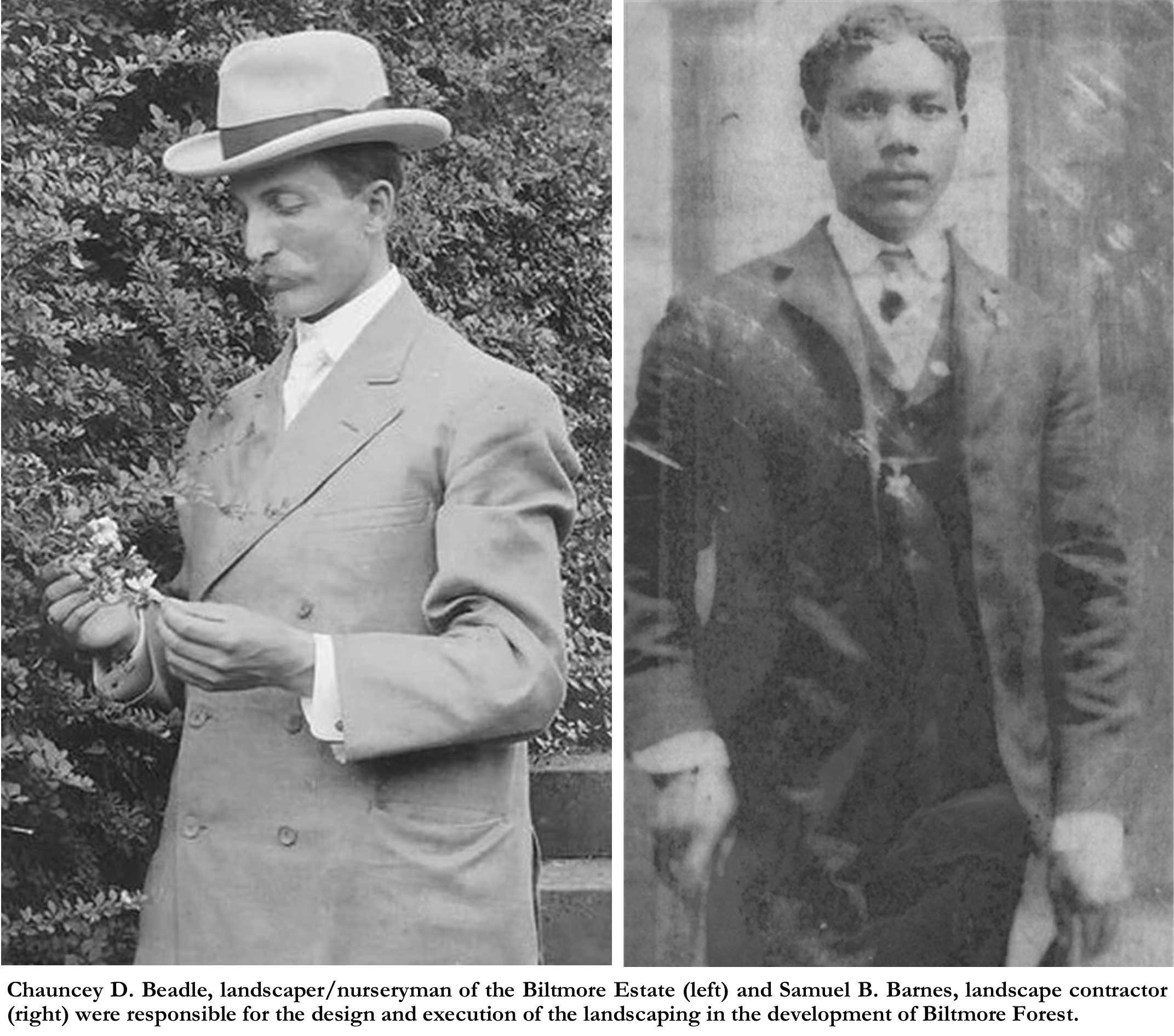

Construction of the new roads and golf course at Biltmore Forest began in earnest at the end of 1920, with Chauncey D. Beadle, head landscaper at the Biltmore Estate designing and directing the road layouts and landscaping for the new development. The Asheville Improvement Company was hired to construct a two-mile stretch of new entrance road from Biltmore Village.[19] The new road, named Vanderbilt Road, started near All Souls Church in the Village and ran through the center of Biltmore Forest. The landscape contracting, though directed by Beadle, was performed by landscape contractor, Samuel B. Barnes. Samuel B. Barnes, an African American had learned his trade under Beadle at the Biltmore Estate, where he had worked on the landscaping crew from 1889-1895, before striking out on his own and forming his own landscaping business.[20] Not only did Samuel B. Barnes, direct much of the landscape contracting, but later would serve as the first greenskeeper of the Biltmore Forest Country Club, from 1922-1924.

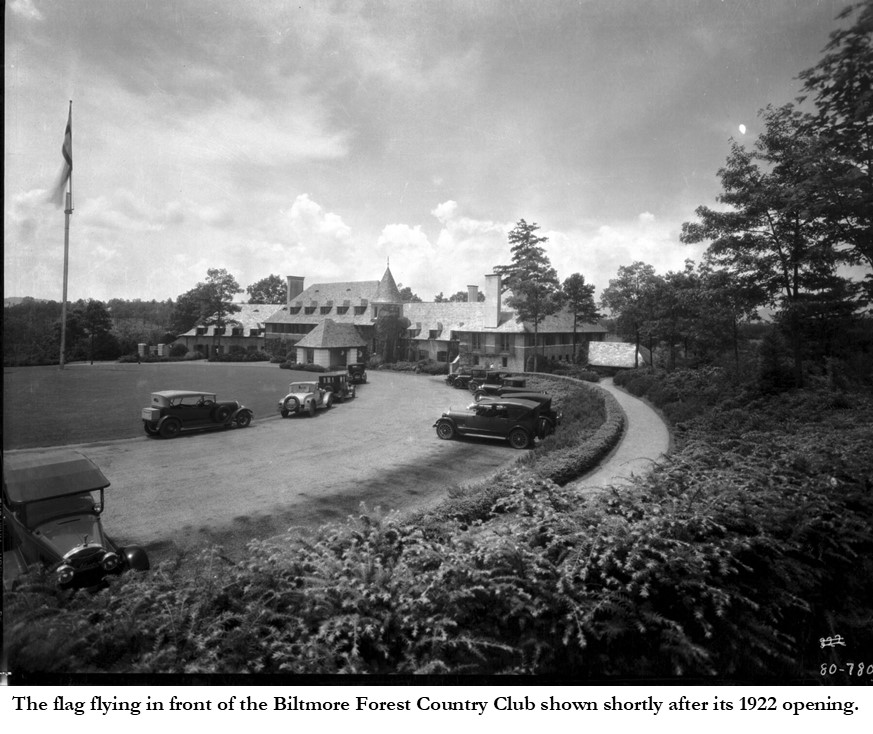

At the start of 1921, the “labor situation” in Asheville started to slow down the work on the new development. In January of 1921, the Biltmore Estate Company’s directors warned that, “work on the club house will not be started until the cost of building in this section is proportional to the lower costs in practically every other locality in the South.”[21] And then on February 27, 1921 the Asheville Times, reported that, “Construction of the clubhouse and three residences on the Biltmore estate property, on the Hendersonville road, South Biltmore, is being held up pending the decision of local labor in regard to wages.”[22] It was further reported that Thomas W. Raoul, had told a “Times representative” that “Under the present wage scales, the company does not feel itself in a position to start actual construction.”[23] In July of 1921, it was announced that the grading of the site of the new clubhouse for Biltmore Forest Country Club had begun, but that actual construction was not to start until September.[24] A month later, the Biltmore Estate Company’s advertisement started to include an architectural rendering of the proposed clubhouse, designed by Baltimore architects, Edward L. Palmer and William D. Lamdin.[25] Finally, on July 4, 1922, on a wet soggy day, the Biltmore Forest Country Club was officially dedicated and opened by Edith Vanderbilt, accompanied by the raising of the U. S. Flag on an “identical flagstaff the late George W. Vanderbilt erected when Biltmore Village was founded.”[26]

In September of 1920, it was announced that the first four houses to be built in Biltmore Forest were just about to begin construction. The four houses were to include: a brick residence for Dr. W. P. Mason on a four-acre tract along Hendersonville Road to be designed and named after the Masons’ ancestral home “Gunston Hall;” and houses for three of the Biltmore Estate Company officers, B. S. Colburn, Judge Junius Adams and Thomas W. Raoul, all three of which, it was announced, would be built near the center of the development bordering on the golf course.[27] The November 1920 issue of “The Manufacturers Record” listed the four residences to be built in Biltmore Forest; “Thomas W. Raoul, erect a $30,000 residence;” “Dr. W. B. Mason, Washington, DC, reported to erect $50,000 residence;” “B. S. Colburn, erect $60,000 residence;” “J. G. Adams, erect $30,000 residence.”[28]

However, due perhaps to the labor disputes of early 1921, and the concentration on completing the Country club and golf course, and other unforeseen variables, the housebuilding schedule was slightly delayed. An August 1921 newspaper report gives us a more detailed and accurate account of the progress of the first houses being built in Biltmore Forest:

Among those who have already purchased property, fronting the [golf] course and who plan construction in the early spring [1922] are: Thomas Wadley Raoul, E. E. Reed, Fred Kent, Dr. Charles L. Minor, M. B. Perkins, Mrs. Emily Street of Jacksonville, and Walter Taylor. Judge Junius G. Adams will complete his residence in about ten days. The residence of B. S. Colburn is under construction and will be finished in late fall. When completed it will be one of the finest dwellings in this community, costing about $75,000.

In Block “A” the following men have purchased sites and plan construction in early spring [1922]: Mrs. Annie R. Borroughs, Dr. J. B. Green, S. L. Forbes, Dr. W. P. Herbert, Dr. W. B. Mason of Washington, Mrs. B. H. Colburn, W. B. Frady. Dr. Carl V. Reynolds is now living on the property and expects to complete his residence very soon. Dr. Mason will erect a large residence, involving an expenditure of about $75,000. It will be patterned after an old colonial home.

In Block “D” comprising smaller lots on the Hendersonville road, lots have been purchased by the following: T. A. Coxe, Jr., Ed Jones, L. Jarrett, Allen Williamson, Dion A. Roberts, Dr. A. F. Toole, and Mr. Kelly. William A. Knight has purchased a site in Block “B” and will build in 1922.[29]

Perhaps all this building and selling activity in Biltmore Forest is what delayed Thomas Wadley Raoul from beginning construction of his own residence, until the Spring of 1922. Raoul and his wife Helen purchased lots 15, 16, and 17, along Vanderbilt Road in February of 1921.[30] Lots 15 and 16 fronted on Vanderbilt Road, but lot 17 which was as wide as lots 15 and 16 together, sat behind the front lots and bordered the golf course. It was on the larger lot 17 that they would build their house, overlooking the golf course. The Raouls chose local architect, Charles N. Parker, to design their new house. Charles N. Parker, originally from Hillsboro, Ohio, moved to Asheville in 1900, following his engineer brother, Harry M. Parker, who had moved here around 1898. C. N. Parker, first worked as a draftsman with noted Asheville architects “Smith & Carrier,” where Richard Sharp Smith was the architect with Albert H. Carrier acting as engineer. In 1913 Parker began working on his own as an architect, and by 1920 had become a noted residential architect, especially in the higher-end neighborhoods of Grove Park and Kenilworth.

Parker chose to design the Raoul’s new Biltmore Forest home in the English Arts & Crafts style, which derogatorily became known as “Mock-Tudor.” First popularized by British architects during the late-Victorian and Edwardian decades, the style was inspired by the medieval country houses which dotted the English countryside, with their picturesque timber-framing, use of brick, stone, and rendering (stucco) for their exteriors, and the quintessential thatched or tile roofs. By the 1920’s, both in Britain and in America, small houses based on the work of those Edwardian Arts & Crafts architects were being designed and built-in post-war housing booms. These “English-type” 1920’s houses utilized re-interpretated medieval details, such as steep roofs, truncated gables and low-swooping roof slopes and projecting entrance porches. Parker no doubt became proficient in this style, while working for Richard Sharp Smith, a British architect who had made the style popular in Asheville with his designs for the cottages on the Biltmore Estate and Biltmore Village.

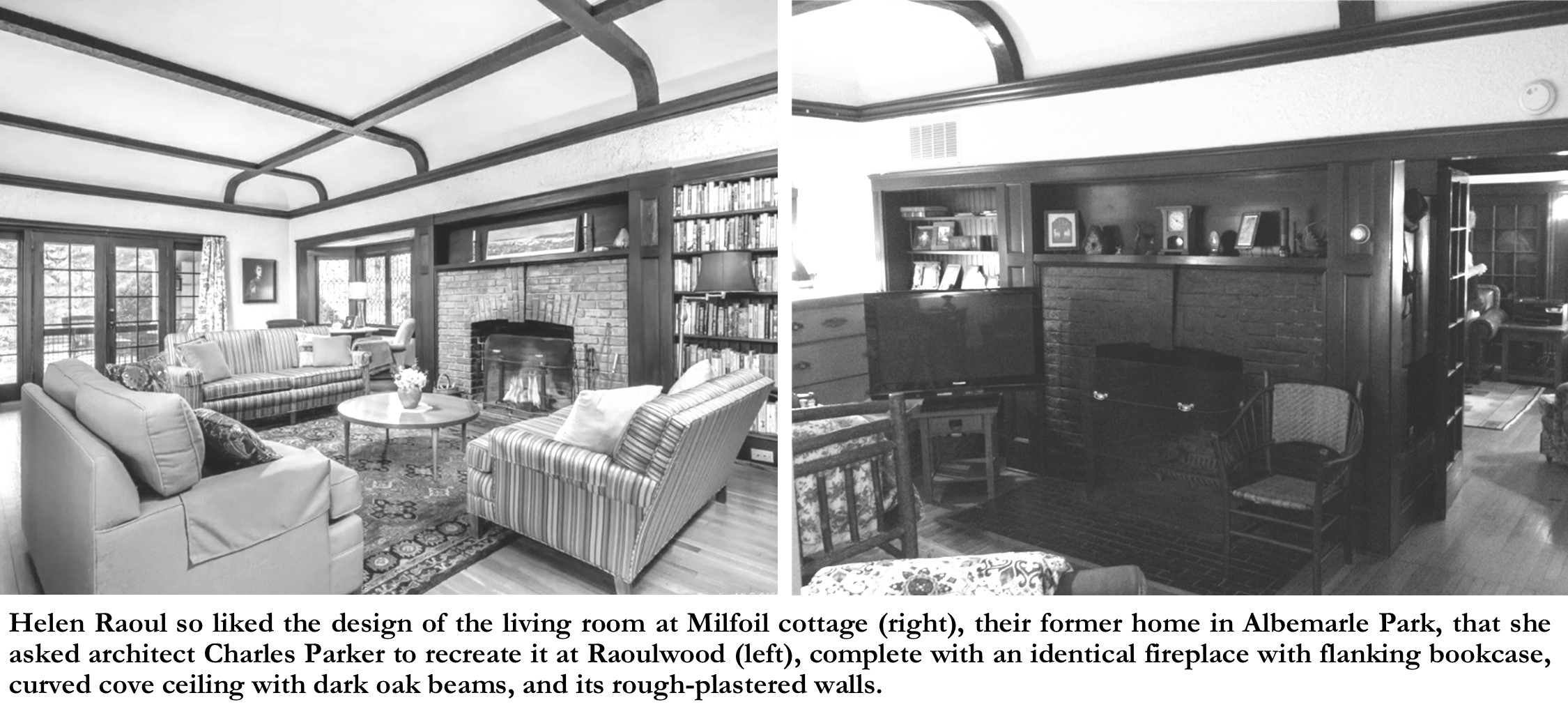

The Raouls had grown accustomed to and admired the English Arts & Crafts style which they had been surrounded by at Albemarle Park. Helen Raoul so liked the design of the living room at Milfoil cottage, their former home in Albemarle Park, that she asked architect Charles Parker to recreate it at Raoulwood complete with an identical fireplace with flanking bookcase, curved cove ceiling with dark oak beams, and its rough-plastered walls. However, the exterior of Raoulwood was not clad in wood-shingles as Milfoil cottage, but instead its exterior featured half-timbering with rough-cast plaster walls. An eye-brow roofed bay window at the home’s interior stair is reminiscent of the eye-brow roofs and dormers used on medieval thatched cottages in Britain. Raoulwood was completed and the family moved in during 1923.

In 1923, Biltmore Forest, through an act of the North Carolina General Assembly, was incorporated into the Town of Biltmore Forest.[31] In 1929, despite ardent opposition, Asheville annexed a portion of Biltmore Forest, but fortunately that action was reversed in 1935 by an act of the North Carolina legislature. Today the Town of Biltmore Forest has over 1,300 residents and maintains its own government, police and fire departments. So many of Biltmore Forest’s original buildings and residences remain, that in 1990, it was determined that the town was eligible to be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places. Although eligible, the town as a whole has not yet achieved National Register status, however, many of its houses have since been listed individually in the Register.

The Raoul family would own and occupy Raoulwood for the next eighty-five years. After the death of Thomas Wadley Raoul’s daughter, Jane Raoul Bingham in 2001, Raoulwood was sold out of the family to Georgi and Elizabeth Kostov in 2008. The current owners, Todd and Angela Newnam, who purchased the home from the Kostovs in 2020, have completely restored Raoulwood to its original glory, while at the same time updating it to modern standards.

Photo & Image Credits: (Note: All cropping and captions by author)

Pisgah National Forest Gate– #76223: Pisgah National Forest Entrance Arch, National Scenic Byways & All-American Roads, U. S. Government. https://fhwaapps.fhwa.dot.gov/bywaysp/photos/76223

Vanderbilt Village Is Sold– Lenoir News-Topic, Lenoir, NC, March 26, 1920, page 3. -newspapers.com

Map Showing Location of Biltmore Forest– The Story of Biltmore Forest, by D. Hiden Ramsey, Biltmore Estate Company, Privately printed [for The Biltmore Estate Company], 1925 – Biltmore Forest (N.C.). -googlebooks.com

General Plan of Biltmore Forest Map– General Plan of Biltmore Forest, Biltmore Estate Company, Ketterlinus Printing House, 1926.

– Southern Appalachian Digital Collections, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC.

Thomas Wadley Raoul & Siblings– Albemarle Park website: http://albemarlepark.org/raouls.html

1921 Biltmore Estate Company Sales Office-Biltmore Estate Archives, Biltmore Company, Asheville, NC.

1923 Biltmore Estate Company Sales Office– Image N213-5- Former Biltmore Estate Company office, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

Chauncey D. Beadle– Biltmore Estate Archives- https://www.biltmore.com/blog/a-special-bond/

Samuel B. Barnes– Image MS403-002E-4 – Samuel Abdul-Allah collection on Samuel Barnes, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

Flag Flying at Biltmore Forest Country Club– (N1933) E. M. Ball Photographic Collection, University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections.

Front of Raoulwood-394 Vanderbilt Road, c. 2020, Realtor.com

Raoulwood Living Room– 394 Vanderbilt Road, c. 2020, Realtor.com

Milfoil Cottage Living Room-59 Terrace Rd; Milfoil Cottage, Leslie & Associates, Inc.- https://www.leslieandassoc.com

Biltmore Forest advertisement– Asheville Citizen-Times, July 10, 1921, page 3. -newspapers.com.

[1] Some of these statistics and facts from: “10 Fast Facts About Biltmore Estate History”, by Heather Angel -09/18/18. – https://www.biltmore.com/blog/10-fast-facts-about-biltmore/

[2] This series ran on Channel 4 in Britain for four seasons, 2009-2012, and is still available via streaming services and online outlets.

[3] The Last Castle, by Denise Kiernan. (New York, NY: Touchstone-Simon & Schuster, 2017), page 179.

[4] Ibid.

[5] See: The Last Castle, pages 186-188.

[6] “The Weeks Act”, Forest History Society- https://foresthistory.org/research-explore/us-forest-service-history/policy-and-law/the-weeks-act/

[7] “WIDOW AND DAUGHTER GETS VANDERBILT’S ALL”, Tampa Tribune, Tampa, Fl, March 13, 1914, page 3.

[8] The Last Castle, page 208.

[9] Ibid, page 213.

[10] Historical Highlights of the IRS, from their website: https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/historical-highlights-of-the-irs

[11] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 20, 1920, page 1. -newspapers.com

[12] Ibid.

[13] The corporation investors of the Biltmore Estate Company included: Burnham S. Colburn (600 shares-$60,000); Thomas Wadley Raoul (20 shares-$20,000); William A. Knight (100 shares- $10,000); and Junius G. Adams (100 shares- $10,000). -07/19/1920 Biltmore Estate Company, incorporation, Deed book, C005, page 322. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[14] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 20, 1920, page 1. -newspapers.com

[15] Ibid.

[16] The Story of Biltmore Forest, with A Forward, An Observation by D. Hiden Ramsey. By The Biltmore Estate Company, Asheville, NC, 1925.

[17] “The Appalachian Playground”, The Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, NC, November 17, 1920, page 6.- newspapers.com

[18] Biltmore Forest advertisement, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 10, 1921, page 3. -newspapers.com.

[19] “WORK PROGRESSING ON BILTMORE ESTATE PARK”, Asheville Times, January 2, 1921. Page 12. -newspapers.com

[20] Asheville Citizen-Times, September 15, 1917, page 9. -newspapers.com. “FOR SALE- My services in landscape gardening, planting and transplanting of all kinds. trimming and decorating trees. Sam B. Barnes, landscape artist. Biltmore, N.C.”.

[21] “WORK PROGRESSING ON BILTMORE ESTATE PARK”, Asheville Times, January 2, 1921. Page 12. -newspapers.com

[22] “CONSTRUCTION BEING HELD UP IN BILTMORE”, Asheville Times, February 27, 1921. Page 2. -newspapers.com

[23] Ibid.

[24] “BEGIN GRADING FOR CLUB HOUSE”, Asheville Times, July 25, 1921, page 10. -newspapers.com.

[25] Asheville Times, August 30, 1921, page 7. -newspapers.com.

[26] “COUNTRY CLUB IS FORMALLY OPENED”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 5, 1922. -newspapers.com

[27] “TO BUILD FOUR HOUSES ON BILTMORE TRACT”, Asheville Times, September 19, 1920, page 5. -newspapers.com

[28] Industrial Development and Manufacturers Record, Volume 78, November 4, 1920. (Southern Association of Science and Industry (U.S.), Industrial Development Research Council, Publications Division, Conway Research, Incorporated, page 182.-googlebooks.com

[29] Asheville Times, August 21, 1921, page 12. -newspapers.com

[30] 02/12/1921 Biltmore Estate Company; Central Bank & Trust Company, TR to Thomas Wadley & Helen Raoul LOTS 15 16 17 BLK G C A BK 2 P 34 VANDERBILT RD Db. 240, pg. 499. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[31] “An Act to incorporate the town of Biltmore Forest, in Buncombe County, North Carolina”, State of North Carolina: Private Laws Enacted by the General Assembly At the Session of 1923. (Raleigh, NC: Mitchell Printing Company, State Printers, 1923), pages 198-200.