by Dale Wayne Slusser

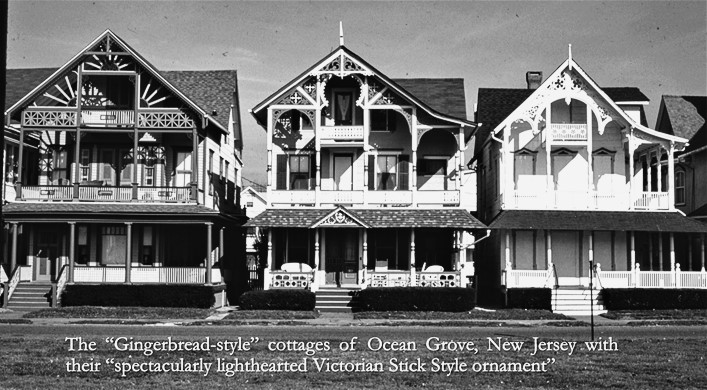

The development of Montreat, North Carolina was the product of the blending of two Victorian social movements- the camp meeting, and the railroad promoted health and pleasure resorts movements. The original concept for Montreat was, according to its founders, to be “a religious settlement somewhat on the plan of Ocean Grove, N. J.”[1] However, the design motif used for the early Mountain Retreat campus and village, was not the ornate whimsical-cottage design of the Ocean Grove camp-meeting village, but was instead the rustic-style, reminiscent of the Adirondack health/pleasure camps developed in New York State beginning in the mid-nineteenth century. This original rustic-style design motif for Montreat was evidenced in the design of four of its earliest cottages, built between 1898-1899, for Dr. Mary Holbrook, Miss Mary Martin, Miss Cora Stone, and sisters Miss Adeline Green and Miss Louise Green. The rustic-style of these earliest cottages continued to inform the designs of cottages and structures for the ensuing two decades of Montreat’s development.

Rising out of the field preaching of the Wesley brothers (Revs. John & Charles Wesley), and combined with the wild ruggedness of the American frontier, circuit riders carried the gospel from place to place in early American history. Preaching in the open air became a regular event for some.[2] These open-air gatherings became known, singularly as the “camp meeting”. The term “camp meeting” signifies a rural Protestant revival held over several days and nights, wherein participants utilized temporary living accommodations–typically wagons or tents–and prepared food on the grounds in order to attend multiple outdoor services. Eventually dominated by Methodists and Cumberland Presbyterians, camp meetings routinely attracted several thousand people, thus creating temporary communities larger than most permanent ones in many regions.[3] Since publicity travelled by word of mouth and travel was often arduous, these religious meetings would last for multiple days and so people often pitched tents to stay for the entire event. Soon these camp meetings became annual events held at the same location and people began to build permanent structures, such as a tabernacle and cottages or cabins. By the 1830’s such permanent campgrounds were common, especially in the northeast.

Alongside the rise of the camp meeting movement, was the Chautauqua movement. In 1874, John Heyl Vincent and Lewis Miller rented a Methodist camp meeting site, on the Chautauqua Lake, located in southwest New York, to use in the post-camp meeting season as a summer school for Sunday school teachers; this became known as the Chautauqua Institution and reflected a nation-wide interest in the professionalization of teaching. Vincent and Miller were very clear that their intent was educational, rather than revivalist. It should be stressed that the Chautauqua Institution was never affiliated with any one denomination; pretty much every faith group in the U.S. has a chapel or building on the grounds today. Still, the sort of mild Protestantism that has informed much of American culture was an underpinning of the Chautauqua Movement.[4] Soon, after the Chautauqua Institution was established, permanent communities called “Independent Chautauquas”, could be found throughout the US and Canada by 1900. Often these were in conjunction with camp meeting establishments and included a “tabernacle”.

In June of 1897, shortly after the property transactions were completed, work began in earnest on Mountain Retreat Association’s new property to prepare for its first assembly, scheduled to begin on July 20, 1897. A contemporary report announced that “Tents are to be put up and a pavilion for religious services of large proportions are being constructed.”[5] Although it was true that tents were used to house the 1897 assembly attendees, the proposed pavilion “for religious services of large proportions”, in reality turned out to be not only more humble in its proportions, but in fact was not even a pavilion, but instead was a rustic assemblage of wooden benches facing a rustic three-sided covered arbor to shelter the speakers. In addition, a dining tent and rustic framed, and boarded kitchen completed the “assembly site”. This first assembly site had the look of the old-time camp meeting with the rusticity of an Adirondack campsite.

As preparations were taking place on the assembly site on the Mountain Retreat Association’s property for its first assembly, concurrently surveyors and architects were busy on the property preparing plans for future development of the site, which was to include a hotel, more permanent assembly buildings as well as “cottages” to be developed in what would become the village of Montreat. Even as the lots were being surveyed and laid out, many of the lots had already been “taken” by individual lot owners. Although the lots were leased to the lot owners, the lot owners had to pay for the construction of their cottage, but then would own the cottages that they would erect on their lots. This arrangement was similar to today’s mobile home parks and condominium developments. Four of the first cottages erected, were the result of the connections and influence of missionary doctor Mary A. Holbrook. From a June 1897 newspaper article titled, “What the Mountain Retreat Association Proposes to Do”, the Asheville Citizen Times reported that: “Among the ladies that have taken lots is Miss Mary A. Holbrook, M. D., a returned missionary from the American board. She proposes to erect two or three cottages and make them headquarters for missionaries returning from the foreign fields. Miss Holbrook has had long experience as a member of the building committee of the board for a number of years in the Sandwich Islands, China and Japan, and her experience in beautiful and yet comparatively inexpensive cottages will be of great value.”[6]

Dr. Mary Anna Holbrook was born in 1854 on a farm in Rockland, Massachusetts, to farmer Richard Q. Holbrook and his wife. Prior to her arrival at Montreat, Dr. Holbrook had already had a long and successful career as a foreign medical missionary. Mary Holbrook entered the Mt. Holyoke College in 1876, where she soon felt the call to missionary work. Mount Holyoke College (first called Mount Holyoke Female Seminary) was founded in 1837 by chemist and educator Mary Lyon, nearly a century before women gained the right to vote. Today, her famous words—”Go where no one else will go, do what no one else will do”—inspired generations of women students to serve as missionaries both in the U.S. and foreign fields. In 1861, the three-year curriculum was expanded to four, and in 1893 the seminary curriculum was phased out and the institution’s name was changed to Mount Holyoke College.[7] After completing her studies at Mt. Holyoke (without graduating) in 1878, Mary Holbrook immediately enrolled at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor to study medicine, graduating with a medical degree in 1880. After a six-month internship at a hospital in Boston, at the age of 27, Dr. Mary A. Holbrook was assigned to serve at the Tung-cho Station in China, serving with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), a Protestant agency founded in 1810 and chartered by the state of Massachusetts in 1812.[8] After just five years, in 1886, Dr. Holbrook had to return to U. S. due to poor health caused by a severe case of cholera. After a period of recuperation, she was hired to teach for two years (1887-1889) at Mt. Holyoke, where she recruited a group of students to assist in a plan to establish a Mt. Holyoke College in Japan. Although the American Board never approved their plan, this same group of students along with Dr. Holbrook applied to the Board and were approved for service in Japan. Mary Holbrook and student Cora A. Stone were the first of the group to set sail for Japan in 1889, bound for Kobe College in Nishinomiya, Hyōgo, Japan.[9] Dr. Holbrook returned to the U. S. in 1894, along with fellow-missionary Cora Stone, who had been diagnosed with tuberculosis.[10] Although Dr. Holbrook returned to Japan, briefly, she returned back to the states in Fall of 1896.[11]

In the same June 1897 newspaper article that reported that Dr. Mary Holbrook had purchased several lots at Montreat, it was also reported that: “H. H. Nutting, a prominent New York architect, is now on the ground, and has already begun making plans for cottages. He has taken a lot and will remain there permanently.”[12] Is this a report of an architect and his client? I propose that it could be-Let’s take a look at “H. H. Nutting”-who was he and what brought him and Dr. Holbrook together at the same place, at the same time?

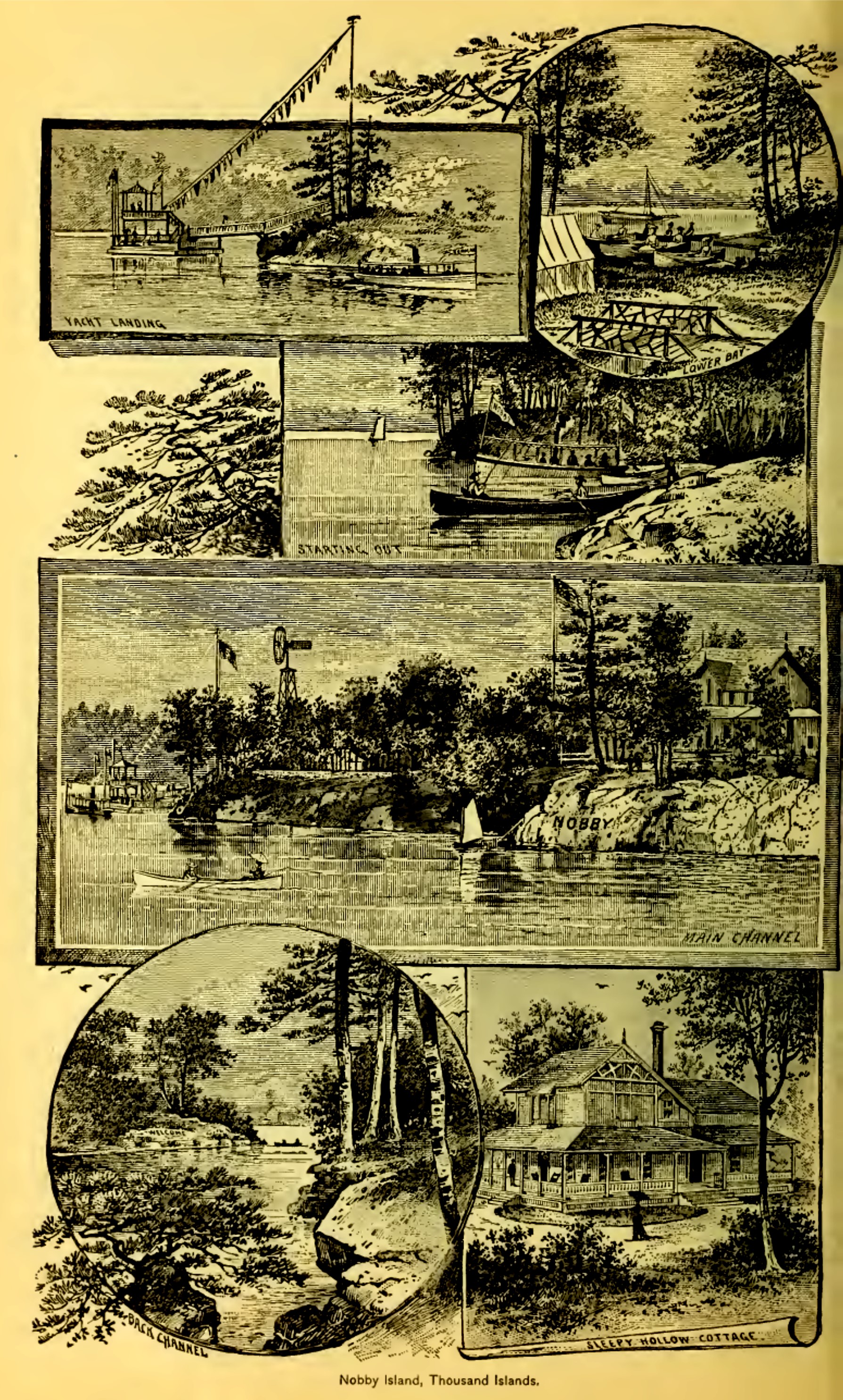

The “H. H. Nutting” mentioned in the newspaper report, was Henry Hodges Nutting, a young architect, who like Dr. Holbrook and Cora Stone, was attracted to Montreat as a respite, as he too was suffering with tuberculosis. Nutting was born on July 27, 1867 to Rev. George B. & Susan Alice Nutting in the country of Turkey, where his parents were serving as missionaries. When Henry Nutting was three years of age, his parents moved the family back to the States, where after six months stay in Connecticut, the family settled in Minnesota where Rev. Nutting had accepted a pastorate. It was in Minnesota that Henry was raised, and where he studied architecture at the University of Minnesota, supplemented later with a course at the Baltimore School of Art. Prior to coming to Montreat in the summer of 1897, Nutting had spent a year living at Lake Saranac in the Adirondacks of New York State, but according to his obituary, he had come to Montreat from “Southern River, N. C.”, where due to “progressing ill heath” he had moved to “two years ago”.[13] A previous newspaper report from July 1897 listed Nutting’s residence as “Southern Pines”[14], which is no doubt more accurate, as Southern Pines was also a popular “health resort” for northerners seeking respite. I believe that in accordance with the report, that Nutting moved to Southern Pines probably in the Fall of 1896, after spending 1895-1896 at Lake Saranac. In June of 1896, the Brooklyn Eagle reported that Henry Hodges Nutting, along with some other men, were spending the summer at “Any Old Camp” on “Fern or Nobby Island, the central and handsomeness island of lower Saranac Lake”.[15] Nobby Island, one of the “Thousand Islands” in that region of New York, was purchased and developed in 1871 (from the Pullman family) by Henry R. Heath, of Brooklyn, NY. Shortly after Nobby Island was developed, the Syracuse Daily Standard described it in this way:

“The island is situated about half a mile from the mainland — nearly opposite the Thousand Island House and is in close proximity to the celebrated “Pullman Island,” and rivaling it in beauty. Upon it are two Swiss cottages, in one of which are dining room, kitchen and bedrooms; in the other are sleeping rooms exclusively. Rustic seats are arranged in shady places at different points, hammocks are suspended, and tents are pitched. Through the centre is a beautiful glade, in which are many chairs, games, etc., affording a lolling place for the idle and pleasant pastime for those energetic enough to handle a mallet or throw a ring.”[16]

Although Nutting was reported to be camping on Nobby Island in June of 1896, I suspect that his “permanent resident” may have been in a house in the town of Saranac Lake on the mainland. Perhaps he even lived in one of the prolific “cure cottages” which had flourished in Saranac Lake in the late Victorian age, which saw the rise of the development of the Adirondacks as a popular get-away destination for Victorians needing recreation or respite. Whether or not, Nutting spent his entire year at Lake Saranac on Nobby Island or in the nearby village, is not important, but what is important is that by the time he reached Montreat in 1897, he was familiar with, having experienced it firsthand, the then popular architectural style, now called the Adirondack Rustic Style, being proliferated on the islands and in the “Camps” of the Adirondacks.

The Mountain Retreat Association’s founders claimed that they used the Ocean Grove, New Jersey camp meeting, as their model, for the development of Montreat. Ocean Grove was founded in 1869 by a group of Methodist ministers, led by William B. Osborn and Ellwood H. Stokes, on the New Jersey coast, for a place for where “religion and recreation should go hand in hand.”[17] In 1870 the New Jersey State Legislature granted the Ocean Grove Camp Meeting Association a charter setting Ocean Grove aside as a place of perpetual worship to Jesus Christ. Promoting that original purpose remains vital as the Camp Meeting continues to this day, providing a place for spiritual birth, growth and renewal.[18] Ocean Grove and Montreat were similar in concept, that is, for the purpose of providing a designated place where large numbers of Christians could gather “for spiritual birth, growth and renewal”. They were also similar in their development, where attendees were first housed onsite in tents, and later hotels and along with the establishment of a permanent settlement, with permanent residents, building cottages on individual lots. The cottages that were built in Ocean Grove were designed in the whimsical Victorian “Gingerbread-style”, with “spectacularly lighthearted Victorian Stick Style ornament”.[19]

Although developed with a similar concept as Ocean Grove, when it came to the design of its physical structures, and site development, Montreat’s founders chose to design their campus and village using the aesthetic of the Rustic-style architecture, exhibited in the Victorian resorts and camps being developed in the Adirondacks in New York State. Not only did the mountain setting of Montreat demand a site-specific design alternative from the whimsical Victorian seaside architecture of Ocean Grove, but Montreat’s early design motifs were a result of the design sensitivities and experiences of those first design professionals responsible for its early development, specifically two relatively unknown architects, H. H. Nutting, as well as Frank Elwood Brown. Like the majority of Montreat’s founders and its earliest residents, both architects were from the New York or New England area in the upper northeast.

According to author, Harvey Kaiser, in his book, Great Camps of the Adirondacks, several factors influenced the emergence of the Adirondack “camps” and corresponding Adirondack Rustic Style. “Early in the nineteenth century, the spread of British architectural and landscaping ideas overlaid by the writings of Andrew Jackson Downing, Alexander Jackson Davis and Calvert Vaux promoted a respect for the natural environment. Hudson River School painters inspired an appreciation for the Adirondack wilderness, and travel writers extolled the American landscape. In addition, post-Civil War industrialization generated discretionary income, enabling an escape to the wilderness, which included the satisfying recreation of hiking, hunting, and fishing.”[20] In addition to the Victorians need for recreation, another important factor which influenced the emergence of the rustic “camps” and retreats in the Adirondacks was the rise of the “health resort”. Health travel came into vogue in the mid eighteenth century, when European physicians began to recommend a “Change of Air” to patients suffering from such nervous ailments as melancholy and hypochondriasis. The purpose of the Change of Air was to revitalize the patient by coaxing a focus on “new objects” in new locales.”[21] There was no consensus among physicians as to which geographic locations were better for which diseases, or which symptoms improved in which locales. Most nineteenth-century doctors did agree, however, that one disease was more fearsome than any other: tuberculosis, then known as phthisis, consumption, or more poetically, as “The White Death”. Because consumption [tuberculosis] had no cure, all its treatments were palliative; they involved making the patient as comfortable as possible in the right climate, so the body could, in the fulness of time, possibly heal itself.[22] Getting outdoors, into the wilderness and the mountains with its fresh cool breezes (air) was a favorite for Victorian “health seekers”. The U. S. Railroad magnates soon saw the income-potential in transporting these health seekers to their desired destinations, and so they enthusiastically supported and promoted these “health resorts”, using such promotional publications as the 1890 brochure titled, “Health And Pleasure, on America’s Greatest Railroad- Being a List of the Summer Resorts and Excursions Routes of the New York Central & Hudson R. R. for the Season of 1890.”[23]

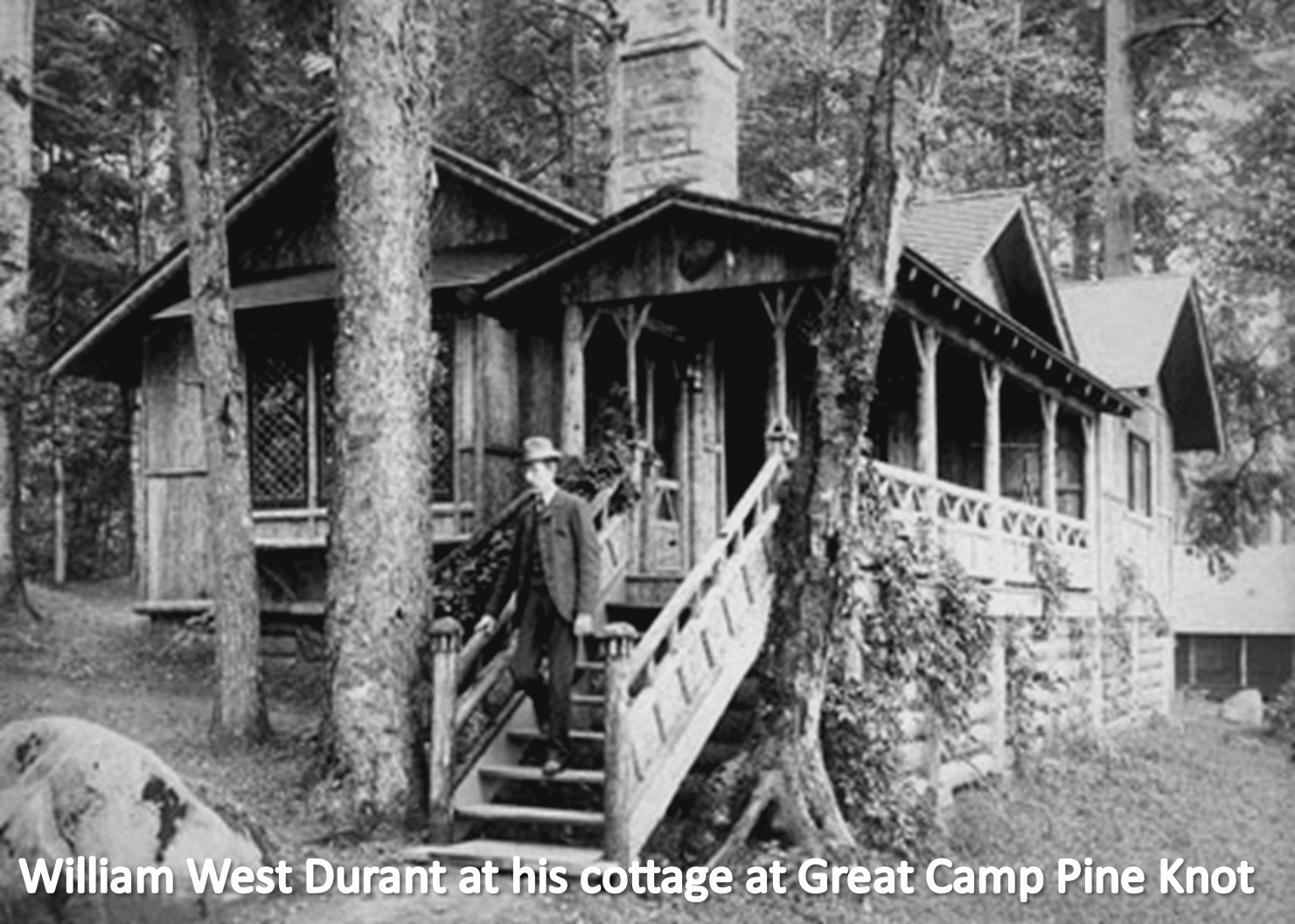

The father of the Adirondack Rustic Style was William West Durant. In 1876, William Durant’s father, Dr. Thomas Clark Durant, railroad builder, purchased large tracts of the Adirondacks in upstate New York, intent on opening and developing the Adirondacks as a summer resort. He hoped this effort would be facilitated by his rail line, the Adirondack Railway Company. Following local building styles, Dr. Durant’s earliest camp dwellings were log cabins constructed of bark-clad logs with wide, overhanging eaves. But it was Dr. Durant’s son, William West Durant (1850-1934), who formulated the hallmarks of Adirondack rustic architecture, when between 1876-77, William began to transform his father’s camp, Camp Pine Knot at Raquette Lake, into an artistic rustic retreat for wealthy vacationers. At Camp Pine Knot, William Durant combined many architectural precedents: indigenous Adirondack log cabin and lumber camp construction; the English Picturesque and naturalistic motifs for country homes placed in wild settings; the Swiss chalet; and Japanese decorative and aesthetic elements to form a unique style of rustic character, detail, and color. Durant’s Camp Pine Knot can be said to be the progenitor of the Adirondack “great camp” and the model for Adirondack-style rustic architecture.[24]

Dr. Mary Holbrook, in the previously mentioned 1897 report, was reportedly intending to “erect two or three cottages and make them headquarters for missionaries returning from the foreign fields”. Apparently to the that end, she purchased lots 59 and 60, on the “Upper Road” (Mississippi Road). Although these were the only lots she purchased, and lot 59 was the only one on which she erected a cottage for herself, I believe her intentions were fulfilled as she was, to varying degrees, directly involved in the building of at least four cottages: her own, now called “Caledonia” (184 Mississippi Road); as well as “Grayrock” (140 Woodland Road); “Hickory Lodge”, now called “Sillwood” (188 Mississippi Road); and “Chinquapin” (300 Georgia Terrace). All four cottages were built in a similar rustic-style, and all built for single women, and three of the cottages were built for women with ties to Mount Holyoke College, which was not only Dr. Holbrook’s alma mater, but also where she taught for several years. Dr. Holbrook certainly acted as the contractor for a few if not all four of these cottages and may have even swung a hammer. Cora Stone, who owned Grayrock cottage, once related that those early cottagers, who were few in number, had to take up roles that were far from their chosen professions. Obviously referring to Dr. Holbrook, Cora related that “the physician was head-carpenter.”[25]

I suspect that Dr. Holbrook’s cottage was the first to be built of the four. On September 3, 1898, Mary A. Holbrook paid $100 to lease lots 59 and 60. She must have begun building her cottage shortly after she finalized the leases, as we know from another source that she was occupying and receiving guests at her cottage by November of 1898.[26] Although she is mentioned in the 1897 report as intending to purchase a few lots, I’m not sure if she was onsite then, however she was onsite by the Spring of 1898, as she’s mentioned often by another visitor and future cottager, Mary Martin in Martin’s letters home. In fact, by the end of her Spring 1898 visit, Mary Martin writes home to her sister in Ardmore. PA, that she had contracted with Dr. Holbrook “who knows a lot about building”, not only to supervise, but “to take entire charge of my house and have it ready for me when I go down in October”. More about Mary Martin’s cottage later, but this reference makes us think that perhaps Holbrook’s own cottage was already under construction, giving Martin confidence in Dr. Holbrook’s capabilities in delivering a satisfactory result.

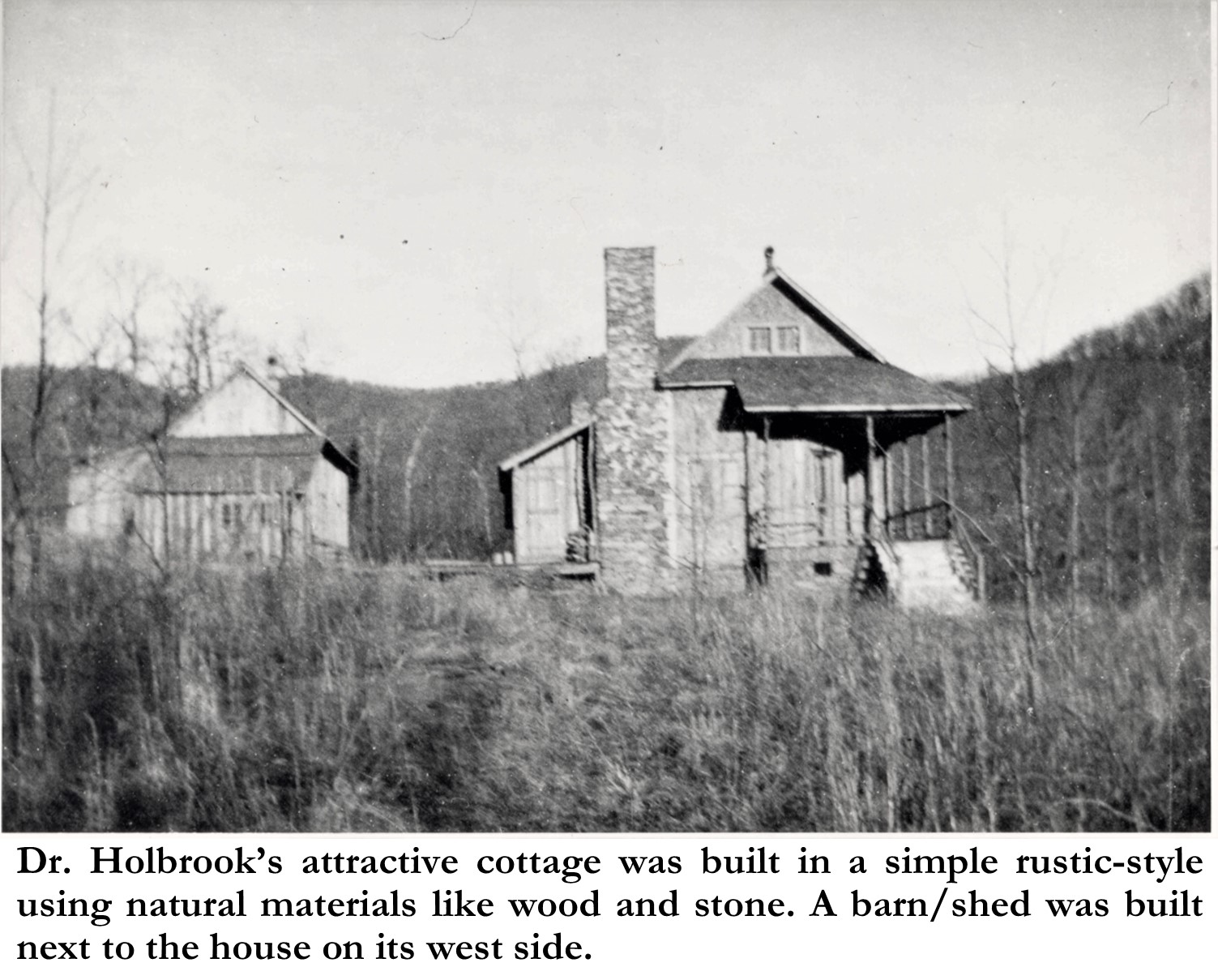

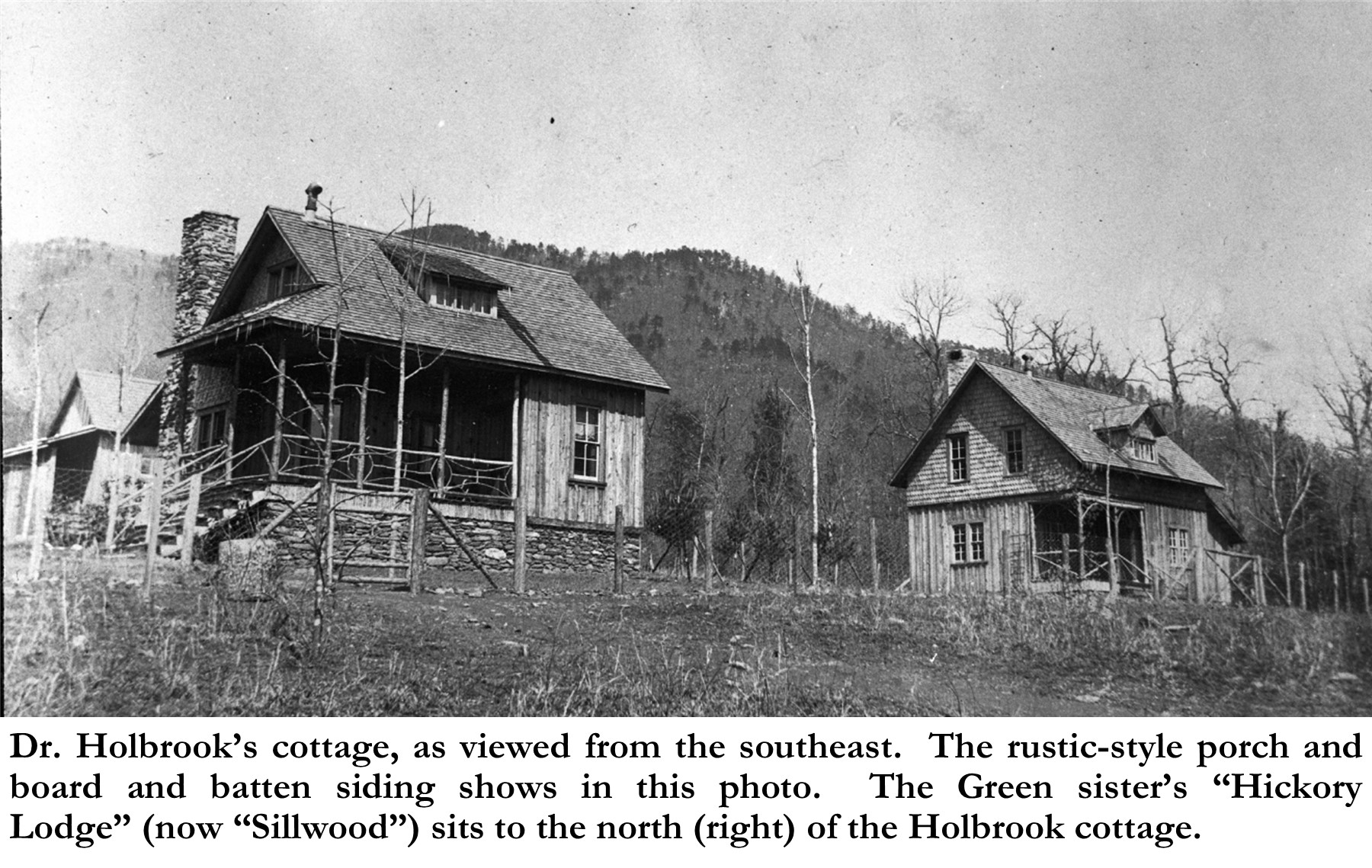

Dr. Holbrook’s attractive cottage was built in a simple rustic-style using natural materials like wood and stone. Although at first glance, it appears to be a simple one-and-a-half story with a steep gabled roof, built without plans, however upon closer look, it is evident that it was no doubt designed by an architect. A first story L-shaped wrap around covered porch smoothly integrated into the main roof. The house was oriented on the site in a north-south direction, perpendicular to the street, with the front gable facing south. The house was entered from the south-facing front stairs up to the short side of the L-shaped porch. The front door was cleverly designed on an angled wall between the south and east walls, making it visible and accessible both from the south and east sides of the porch. A rustic stone chimney with a corresponding angled interior stone fireplace was built on the south wall in the southeast corner. In keeping both with the rustic-style, as well as local tradition on rural houses, the exterior of the first floor was sheathed in narrow board and batten siding. Wood shingles were used on the roofs, and the gables and dormer were covered in wood shakes in a stepped pattern. Perhaps the most obvious rustic-style feature of the cottage was its front porch with tree branches for posts, rails, and balusters. Another rustic feature, which incidentally was shared by the other early cottages, was the cladding of the porch floor rim boards with short pieces of branches placed vertically next to each other. Remnants of this detail remain on the cottage to this day, although now hidden in the crawl space under the modern expanded porch.

The Holbrook cottage included a living room, bedroom or bedrooms and a lean-to kitchen (off the west wall) on the first floor with a second-floor small loft under the steeply pitched roof. A sizeable storage shed, also cladded in board and batten, was built next to the house to the west. A vintage photo shows that the house was enclosed by a wire fence between log posts. The fence was no doubt put up shortly after the house was built, as at the time stock laws were not enforced, so livestock were free to roam. In her letters home between 1898-1899, Mary Martin often mentioned the roaming livestock. Besides the roaming pigs, which were kept in check (chased away) by the three dogs in the settlement, Mary also wrote that “Mrs. Saleno’s cow has a passion for ferns. I had to drive her away four or five times yesterday. She ate my little Wichuriana rose leaving only a hole in the ground.” [27]

In a vintage photo of Dr. Holbrook’s house, viewed from the southeast, we see a similar rustic-styled cottage next door on the adjacent lot to the north. This was a cottage built for sisters, Adeline & Louise Green. Not surprisingly, when choosing a lot in 1898, that Adeline Green chose Lot 58, next door to Dr. Holbrook. Adeline Green came to Montreat at the age of 52 after having a long career as an instructor (professor) of Mathematics and Latin at Mount Holyoke College. Green was an 1867 graduate of Mount Holyoke and began teaching there in 1871, which means that she was teaching there when Dr. Holbrook attended Mount Holyoke in the late 1870’s, and she was also there when Dr. Holbrook joined the faculty from 1887-1889.

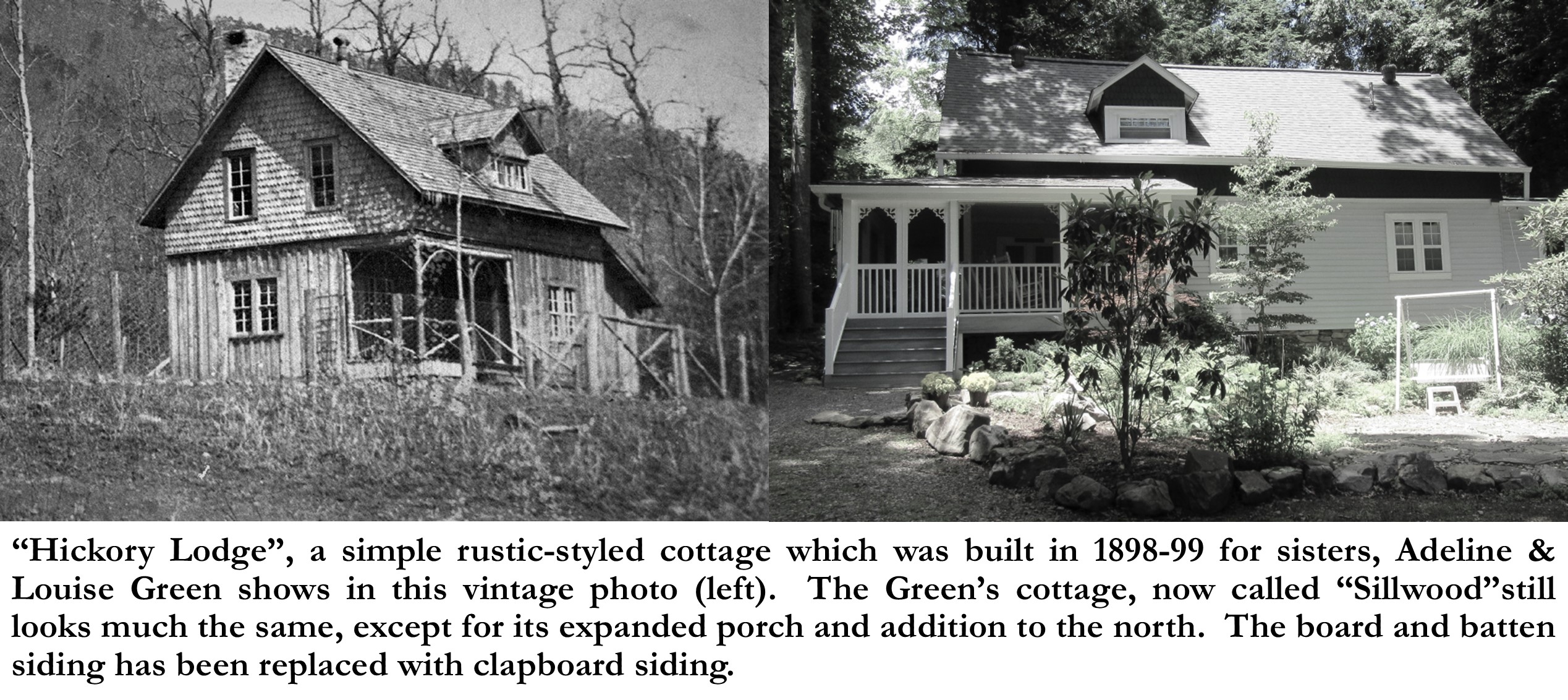

In the previously mentioned passage from Cora Stone where she described the early cottagers who by necessity of having to support themselves, had to assume roles that were far from their chosen professions, she described one of the cottagers, obviously referring to Adeline Green, as “the beloved college instructor of other days” that “kept our boarding house”.[28] Adeline built the small cottage on Lot. 58 in 1898, and immediately began using it as a boarding house. In Mary Martin’s published letters, we get a glimpse into the timeline of the building of the Adeline Green cottage. In a letter dated November 1898, Martin writes: “The Odells [surveyor Frederick Odell], who were with Mr. Lord, have now gone with the Greens and ditto a Mrs. Sperry and her mother.”[29] This is consistent with the timeline for the building of the Holbrook cottage, and would also explain its close resemblance in shape and style to the Holbrook cottage. The Green cottage was built in a similar simple rustic-style with a small rectangular first floor and steeply gabled second floor. One difference from the Holbrook cottage is that the roof bearing sits on low knee walls above the second floor, instead of on top of the first-floor walls as in the Holbrook cottage. This allowed the second floor to have greater headroom for proper sleeping rooms, rather than just having a sleeping loft. Also like the Holbrook cottage, the Green cottage was sheathed on the exterior with board and batten on the first floor and wood shingles on the second floor and roof. The Green cottage, like Dr. Holbrook’s, had a similar small, recessed porch on its southeast corner, with rustic-style tree branches for posts, rails, and balusters. The porch had identical views to the east and south, however the entrance stairs to the Green cottage were placed on the east side, rather than the south. Especially rustic was the porch post brackets which were not only made of branches, but installed in a such a way that they appeared to have naturally grown out of the post. Another rustic feature of the Green cottage porch, also shared by the Holbrook porch, was the cladding of the porch floor rim boards with short pieces of branches placed vertically next to each other.

The Green sisters Addie & Louise (also a Mount Holyoke graduate) lived in their small cottage until 1901 at which time they built a new large modern house, on Assembly Drive, which they opened as a boarding house. They named their new boarding house with the same name as their cottage, “Hickory Lodge”. This we know from a contemporary newspaper report from 1901 which reported: “The Misses Green built during the winter a commodious and airy house near the church, where they welcome the old friends who sojourned in the tiny Hickory Lodge last summer and promise to make them and many new friends much more comfortable this season.”[30] The “tiny Hickory Lodge” had to be their first house, the cottage on Lot 58. The 1900 census supports this as well: Addie Green was listed as “head” in the household, living with her was listed Louise J Green (sister), along with a servant and a boarder from Maryland. Their household was listed in the census next to the Holbrook household in Montreat. The Green sisters held onto their “Hickory Lodge” cottage, no doubt for additional rental income, until 1906 at which time they sold it to John C. & Ella Tharpe. The cottage which remains at 188 Mississippi Road, much as it was originally built, is now called “Sillwood”, named for Henrietta Sill who purchased the property in 1914.

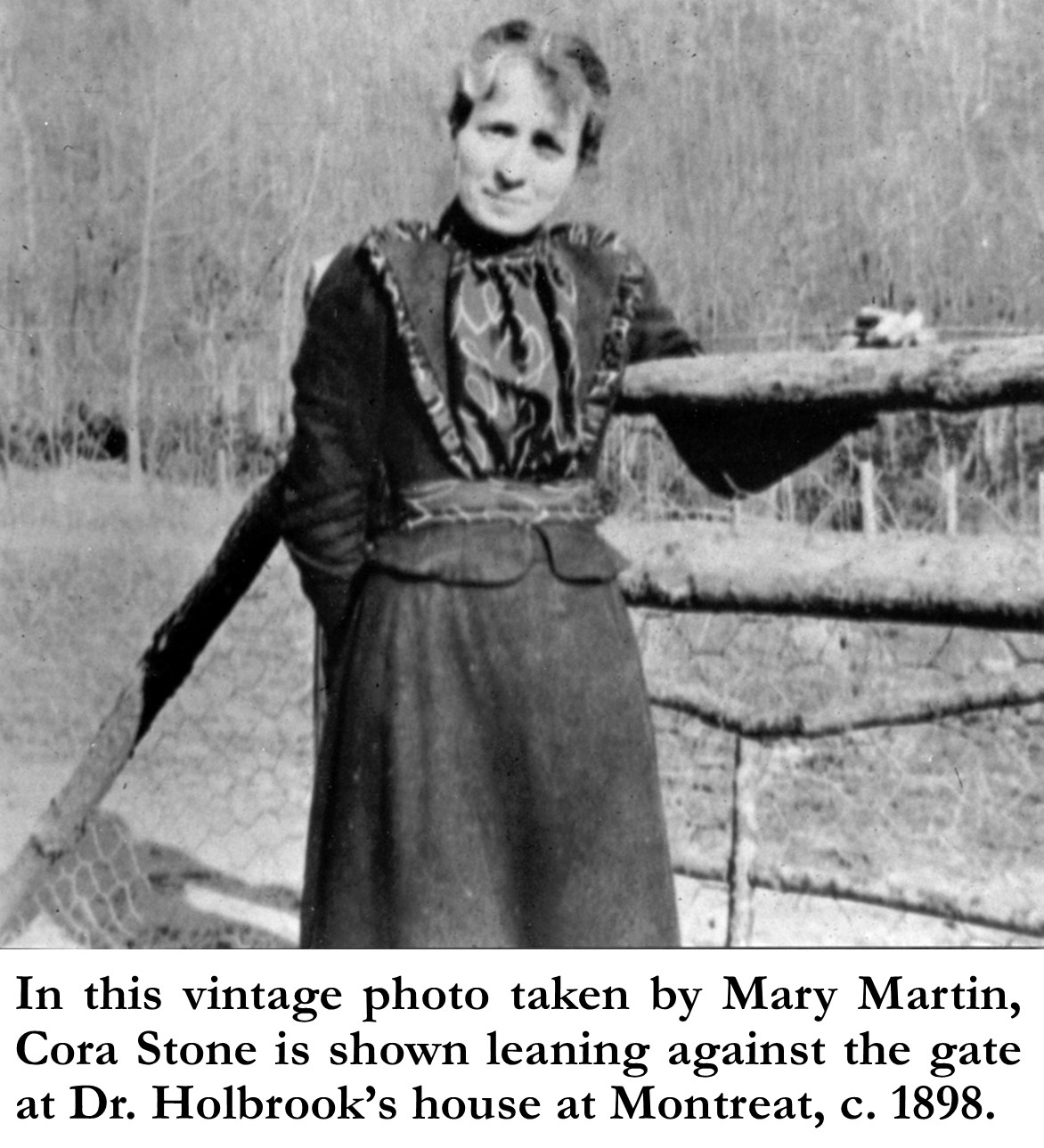

Dr. Holbrook had come to Montreat to rest, but primarily she came to help her young protégé and friend, Cora A. Stone. Cora Augusta Stone was born to Omar & Harriet Stone on September 27, 1867 at Rose Valley, NY. After teaching at an ungraded school near Newark, NY, Cora enrolled at Mount Holyoke College in 1886, and according to her own account,[31] she finished her four-year course in three years, graduating in 1889. On October 3, that same year, she sailed on the S. S. Gaelic from San Francisco bound for Japan to serve as a missionary. After a year at the Okayama station, she was transferred to Kobe College, where she served as an instructor alongside her former college professor, Dr. Holbrook. Although her department at Kobe was “Ancient & Modern History”, due to occasional staff shortages, she also taught English, English Literature, Mathematics and Gymnastics.[32] In February 1892, Cora Stone came back to the states with fellow missionary Lizzie Wilkinson, but Cora returned to Japan in August, where she continued her teaching until her health gave out in 1894, at which time, accompanied by Dr. Holbrook, Cora returned to the states. But after a few years of rest with her family in New York, she seemed to regain her strength, so in 1897 “she went to the University of Michigan to study Greek, hoping to take a higher degree and return to Japan”.[33] But alas her health began to fail rapidly, and having been diagnosed with tuberculous of the lungs and brain, she was a told that she may not live more than three months, especially if she remained in the northern climate.

In February of 1898, Cora Stone, accompanied by fellow missionary Miss Abbie Kent who had returned, due to ill health, to the states in 1897 from teaching at Kobe College, arrived at Montreat. When Miss Mary Martin first visited Montreat in the Spring of 1898, she met Cora and Abbie who were lodging in a second-floor room, across the hall from Mary, at Chester Lord’s boarding house. A few days later, on April 23, 1898, Mary wrote that a few days earlier, when she arrived back to Montreat in evening, after a long “all day drive”, that while they were gone “Dr. Holbrook, a missionary from Japan had arrived.”[34] Martin also recorded that Miss Kent moved in to bunk in Mary’s room, so that Dr. Holbrook could be in Cora’s room, but that the three missionaries were soon to “go into one of the log cabins”.[35] It was not long after Dr. Holbrook’s arrival, I believe, that construction began on Holbrook’s and Cora’s cottages.

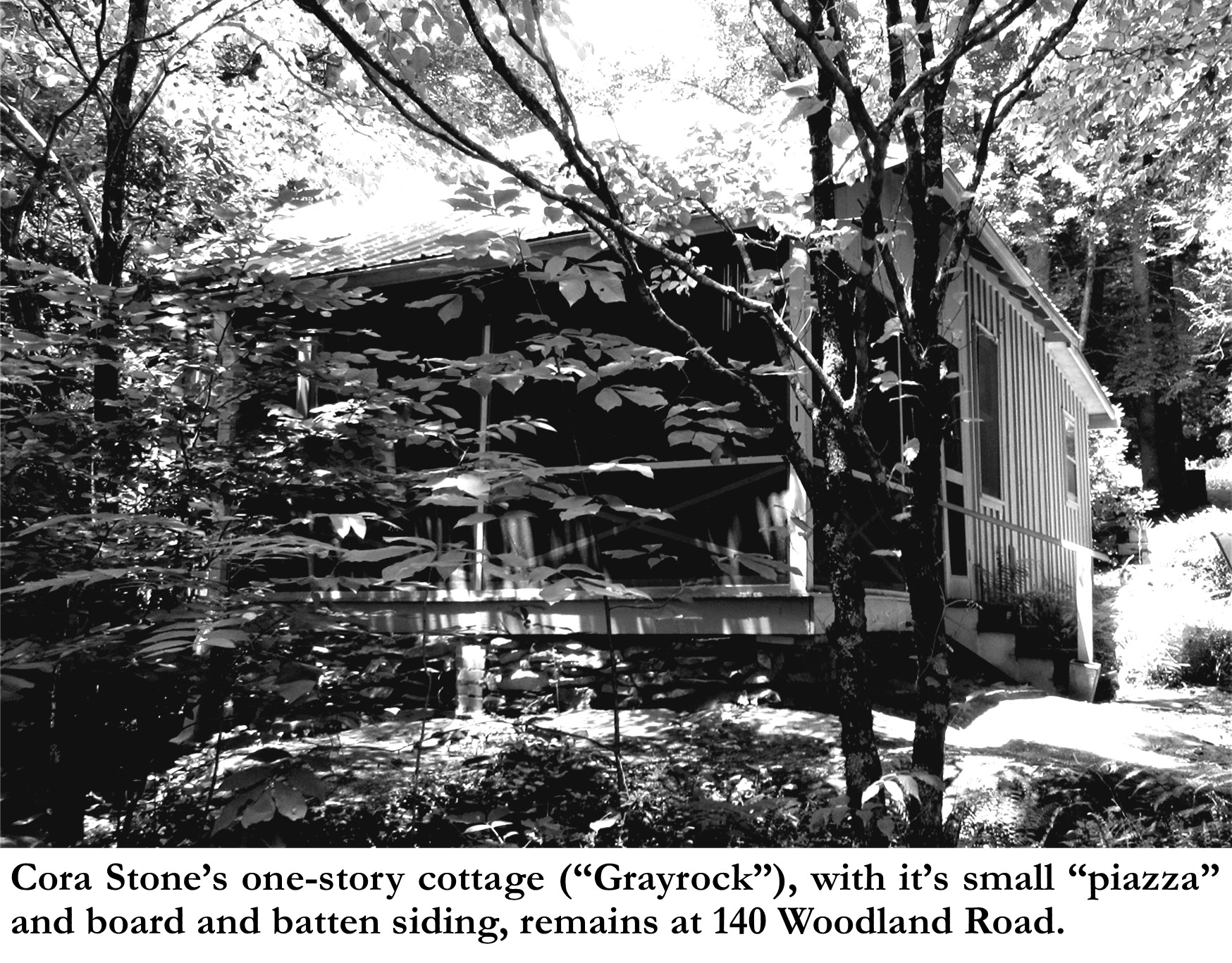

Cora Stone’s cottage was built on Lot 124, across the road and slightly south of Dr. Holbrook’s cottage. Unlike the other early cottages, Cora’s cottage was a single-story with a hipped roof. Although I have found no record that Cora used a wheelchair, I suspect that accessibility was nonetheless a factor in the design of the cottage. Like the other cottages, it faced east, however its porch or “verandah” (as Cora called it) was on its northeast corner. The simple rustic style shows in the exterior walls that were clad in board and batten siding. And although we had no vintage photo of the cottage, I suspect that the metal roof that is currently on the cottage was a later addition and that the roof was originally sheathed in wood shingles. Also, I suspect that the original porch posts and rails were no doubt made of tree branches and twigs.

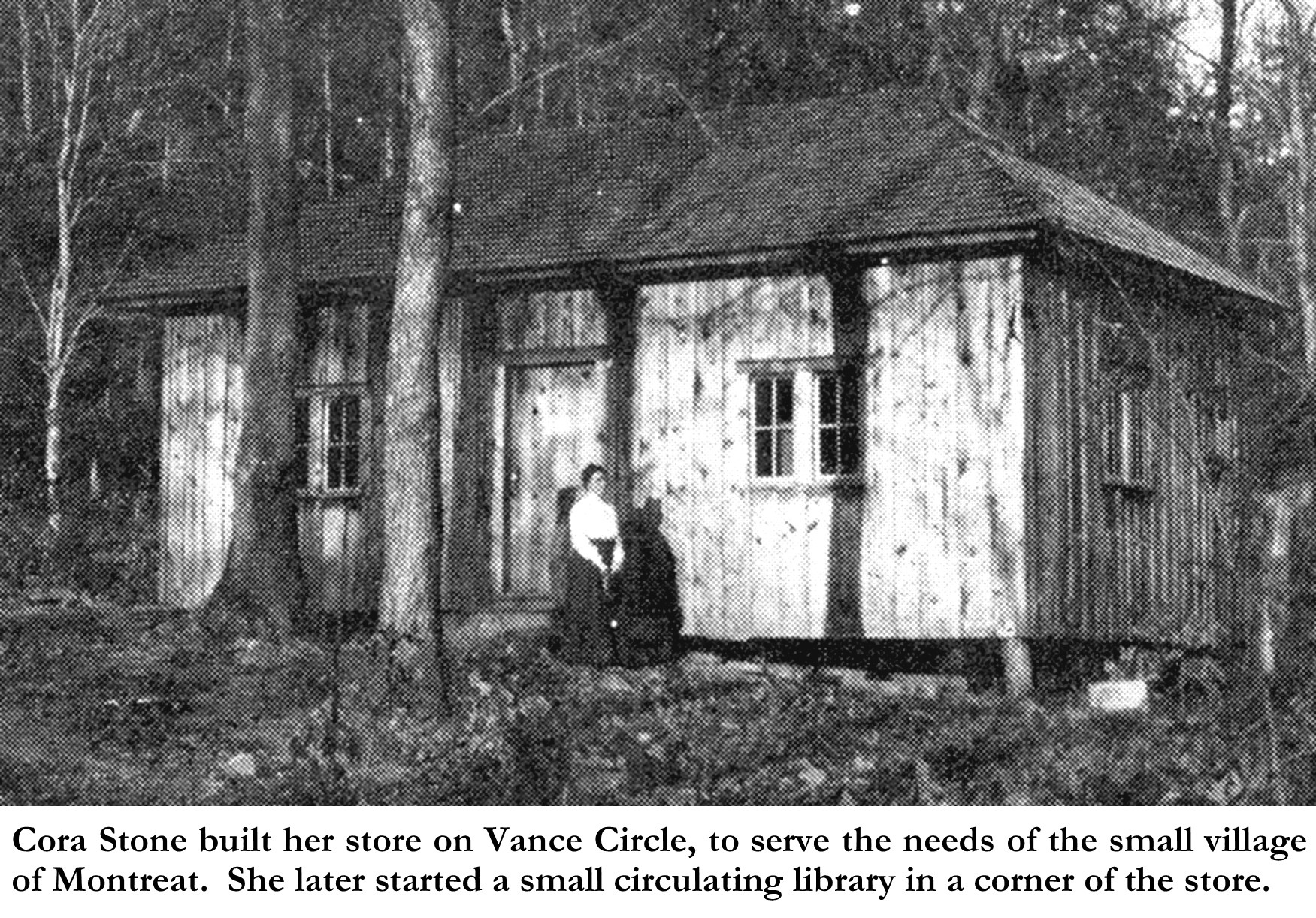

While living in her new cottage, Cora Stone’s health soon rallied and she began looking for a way to serve her new community, and at the same time generate some income to live on. She saw the need for a community store, so that the residents of Montreat, who she once described as mostly “semi-invalids”, would not have to travel over the rough rugged road into Black Mountain for their groceries and supplies. To that end, on January 2, 1899, an agreement was signed between Mary A. Holbrook (with Cora Stone as a witness) and the Mountain Retreat Association for her to set up a grocery and merchandise store on Vance Circle.[36] She was reported to have built and established the store with borrowed capital-no doubt financed by Dr. Holbrook. The new store was designed and built in a similar rustic style with board & batten siding topped by a hipped roof. The store sat on “Vance Circle”, the site now being recognized as on the northside of Louisiana Road, above 202 Louisiana Road near the intersection of Virginia Road. It was later written that, “From the first, the little store, opened only in the mornings, became the center of wide influence. In an alcove of the store, Miss Stone started the nucleus of a library, which when she gave up the charge of it, contained about 1,300 volumes, all collected by her.”[37] She also created a “Circulating Picture Gallery”, made up of framed “Perry Pictures”.[38] The pictures could be ordered from their mail-order catalogs. Cora would order the pictures, and then frame them in “passepartout” (mounted between a piece of glass, sealed on the edges with adhesive tape). “The pictures went one at a time to brighten for a month the walls of many a mountain home”.[39]

In the winter of 1903 (first months of the year), Cora suffered a relapse and had to give up the store, but she then partially rallied during the summer months, allowing her to continue working in the library. But in the Fall of 1903, she “was prostrated by a tubercular abscess”[40] and became homebound. But after a few days, she again rallied enough to “be about her little house again and do some home duties”, and even began to exhibit, “in new and beautiful ways a[n] increased and deepening spirituality”.[41] But she continued to show signs of decline in her health. On August 28, 1904, as Cora Stone reclined on her cottage porch (piazza), knowing in her heart that the end was near, she recorded in her journal, a last message of hope and peace:

“I feel the time is coming for me to join my Lord in the heavenly home He has prepared for me. The new experiences I wonder much about. I’m only sure they will be glorious and satisfying. I find I do not fear death at all. I am in my piazza today, observing the beautiful mountains across from my home. Warmly covered, as usual, I am merely waiting for my Lord to call me…Though I have spent only 36 years on this earth, I believe I have made the most of every minute. I never asked anyone to do anything I would not do myself, and I have attempted exclusively to follow God’s will for my life. Through Him I have positively touched many lives. I am at peace.”

Cora quietly and peacefully passed away in the wee hours (4:00 am) of the following morning, August 29th, inside her cottage, under the tending care of her sister Bertha. Cora Augusta Stone was laid to rest on the following Wednesday, August 31, 1904 at Homer’s Chapel on the North Fork Road, not far from her little cottage. Even her funeral exhibited her adoption of the simple rustic, yet natural, atmosphere of Montreat. Dr. Holbrook described the scene: “The casket was completely covered with galax leaves and clematis. All the platform was one bower of greens and flowers. The floor below where the casket stood was covered with maiden hair ferns and flowers.”

It is not surprising that Cora had left her cottage to her sister Bertha Stone Mackintosh, who not only had tenderly cared for Cora at the end, but who had her own sweet memories of that cottage at Montreat. Just two years earlier on September 11, 1902, Bertha had married Rev. George Mackintosh, a native of Scotland who at the time was the pastor of Third Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis, IN, in the small church at Montreat. “The occasion”, it was reported, “was the first of the kind in the history of Montreat and was a complete success in every detail”.[42] Sadly, Bertha passed away just two years after her sister, dying in 1906, leaving the Montreat cottage to her 2-year-old son Roderick Mackintosh. Although she died in Indiana, Bertha was buried next to her sister Cora in the small graveyard at Homers Chapel near Montreat.

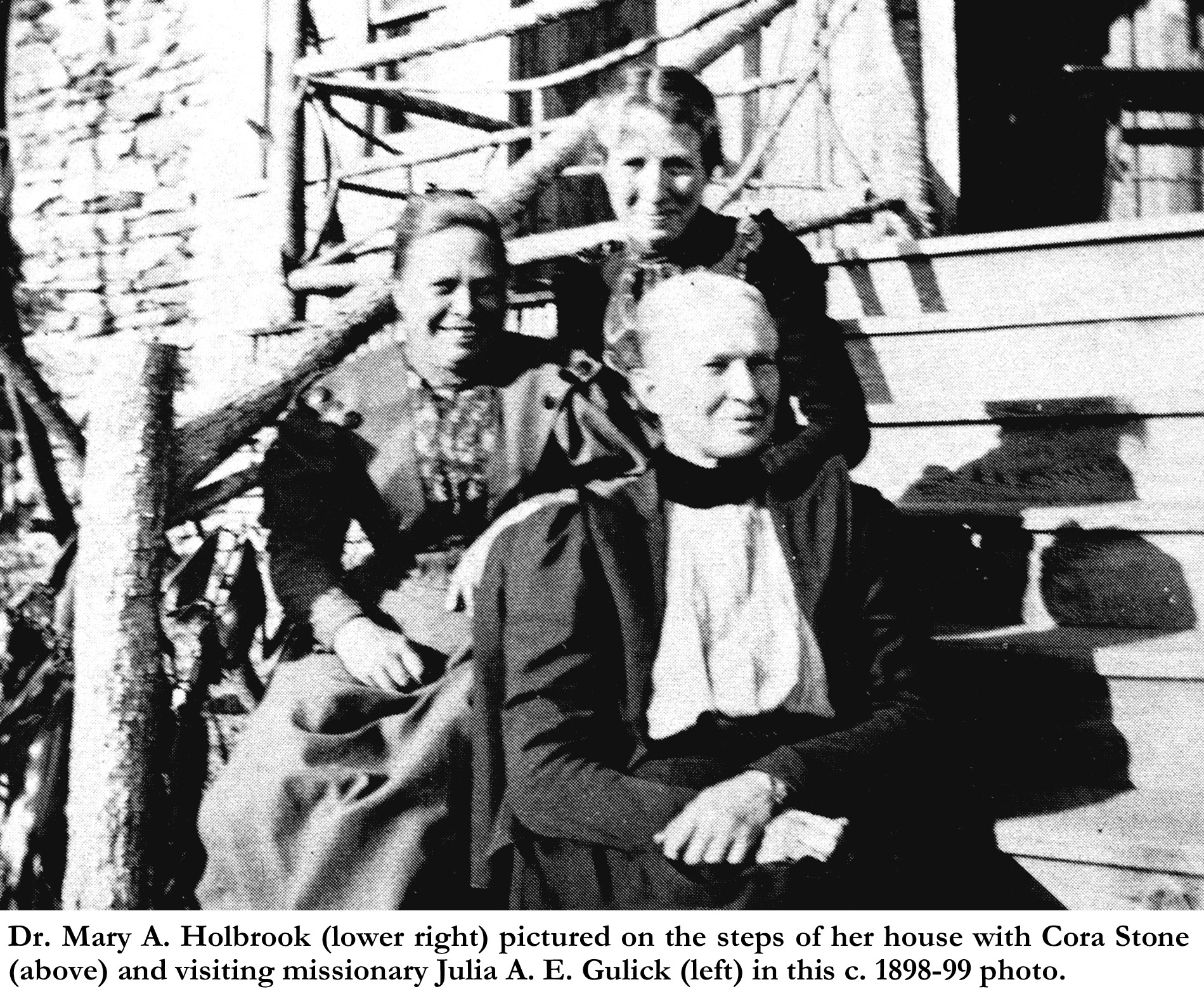

In 1908, Chester Lord, another early Montreat resident, acting as agent, obtained legal guardianship of minor Roderick Mackintosh, for the purpose of selling the Cora Stone cottage (now known as Grayrock). In an interesting twist, the cottage was sold to fellow missionary, Abbie W. Kent.[43] In the 1900 census, Abbie Kent was shown living in a Montreat cottage with her elderly adopted sister Sarah Everett, next door to a cottage occupied by Dr. Holbrook and Cora A. Stone. I suspect that Abbie was living in Dr. Holbrook’s house with her sister and that Dr. Holbrook had moved in with Cora. Supporting my suspicion that these missionaries may have shared these two cottages, swapping places as needed, comes from Mary Martin’s report in 1899 that, “There is a song service every Sunday evening at Dr. Holbrook’s. The three missionaries from Japan all live there: Dr. Holbrook, Miss Stone and Miss Gulick.”[44] Miss Gulick, was missionary Julia A. E. Gulick, a fellow missionary from Japan who was visiting Montreat on her 1899 furlough. One of Mary Martin’s photos show these three missionaries sitting on the porch steps of the Holbrook cottage. Also, In 1901, Dr. Holbrook returned to Japan to Kobe College and following Cora’s 1904 death, in 1905, Dr. Holbrook, from her new home in Japan, officially granted power of attorney to Abbie Kent to sell Holbrook’s cottage to Alice Alden.[45] I surmise that after the 1905 sale of Dr. Holbrook’s cottage, that Abbie Kent may have moved to occupy Cora’s cottage, as Bertha Stone Mackintosh, was living in Indianapolis, leaving the cottage vacant. So, I surmise that Abbie may have already been occupying the Stone cottage, before purchasing it in 1908. Abbie moved into Cora’s cottage with her adopted sister, Sarah Everett, who on the 1910 census was listed at 88 years old. The census mistakenly listed Sarah as the head and owner of the house. Sarah Everett passed away at the age of ninety in the cottage, three years later[46], and was buried at Homer’s Chapel next to the graves of Cora Stone and Bertha Mackintosh. In 1915, Abbie Kent sold the cottage back to the Mountain Retreat Association who immediately sold it to the Ransom family.[47]

Although Miss Mary Martin had the least connection to Dr. Mary Holbrook of all those early single women residents of Montreat, her cottage is the only cottage for which we have conclusive proof that it was built for her by Dr. Holbrook! Mary Rockwich Martin was born on April 5, 1870 in Elizabeth, NJ to Robert W. & Mary F. Martin. During her third year at Bryn Mawr College, near Philadelphia, “her health broke under the strain of college work and trying to care for her invalid parents”[48], and in 1898, her father paid for her to go south to Asheville for respite and restoration, although she was not only discouraged but convinced that she would never again “be well enough to do anything”. But after visiting Montreat for a few days in April 1898, she wrote home that “my stay at the Retreat did such wonders: I felt so strong while there that hope revived and I feel that I have found just the place in which I can live and be strong enough to work.”[49] To that end, before returning back north for the summer, she had not only purchased a lot, but had made arrangements to have a cottage built for her, to be ready for her return in the Fall. Mary had chosen Lot no. 12, which was just southeast of the Chester Lord’s house, where Mary had stayed while visiting Montreat. “Dr. Holbrook, who knows a lot about building,” wrote Mary before leaving Montreat, “is going to take entire charge of my house, & have it ready for me when I go down in October”.[50] Mary Martin later recorded that the Dr. Holbrook had charged her “$25.00 for superintending the building and $33.71 for the cost of the house”[51]-that was quite a hefty commission!

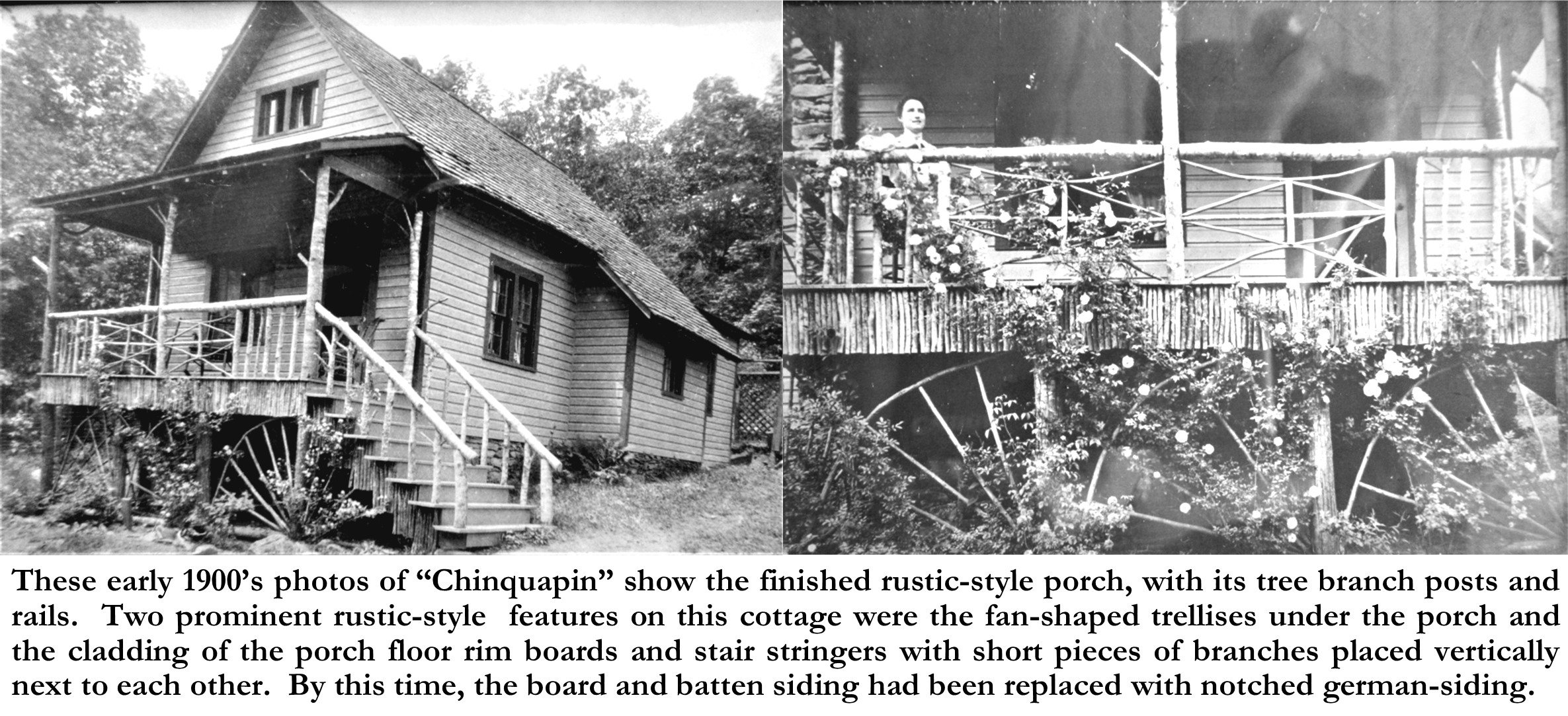

When Mary returned to Montreat in November of 1898, she found that her house was completed (all except for the front porch roof) and ready for her occupancy, with a sign over the front door identifying her new cottage as “Chinquapin Lodge”, and a fire blazing in her new fireplace.[52] Like Dr. Holbrook’s and the Green sisters’ cottages, Martin’s house was built as simple rustic-styled one-and-a-half story with a steeply front-gabled roof. Like the other early cottages, Chinquapin also had a lean-to kitchen (on its southside). It also shared similar rustic-style details of the other cottages, such as the fieldstone chimney, board and batten siding, and with rustic-style tree branches posts, rails, and balusters on its front porch. We are fortunate that Mary Martin had carried a camera with her to Montreat, as we have some invaluable early images of Montreat. In an early photo, taken shortly after she arrived, Mary captured her house still in the course of construction, with exposed porch floor joists, uncut porch post tree branches laying in the front yard, toppled sawhorses in the side yard, and even a workman’s ladder leaning against the stone chimney.

A later photo labeled “1900” (though I suspect it to be later-perhaps 1910), shows the house with its completed rustic-styled porch, however for some reason, probably to make the house more “stylish”, the original board and batten siding had already been replaced with notched German-siding.

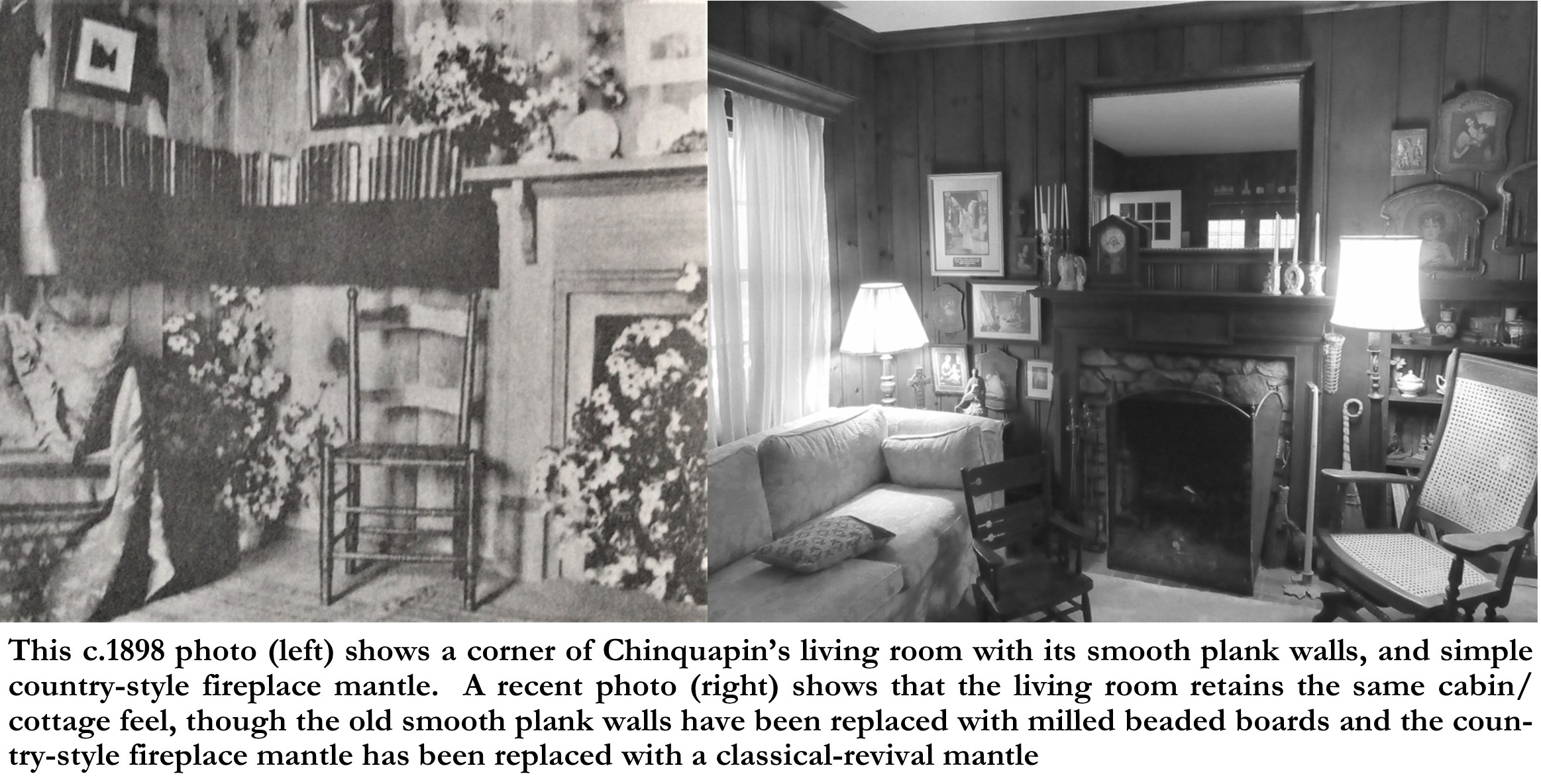

A rare surviving interior photo from 1898, showed a corner of Chinquapin’s living room with its smooth plank walls, as well as its first fireplace with its simple country-style fireplace mantle. A recent photo shows that the living room retains the same cabin/cottage feel, though the old smooth plank walls have been replaced with milled beaded boards and the country-style fireplace mantle has been replaced with a classical-revival mantle. The original Chinquapin cottage, which remains in hands the original family, remains as the nucleus of their greatly expanded family home at 300 Georgia Terrace.

Although I have found no conclusive evidence to prove that architect H. H. Nutting designed all, if any of these cottages, it is plausible to assume that he may have, as he not only was reported to have been onsite during 1897-1898 “making plans for cottages”, but he also had made a deposit on a lot in June of 1898[53], obviously intending to build his own cottage. Unfortunately, Nutting died just a few months later, in September of 1898, from a pulmonary hemorrhage ending his long struggle with tuberculosis.[54] This would have put Nutting onsite both before and during the construction of these cottages. Also, an impelling evidence is that the simple rustic design of these cottages is much like the cottages Nutting saw in the Adirondacks, where he lived for a year. The cottages on Nobby Island, in Saranac Lake, NY, where Nutting camped in 1896, had similar detailing including the board and batten exterior siding with rustic trim.

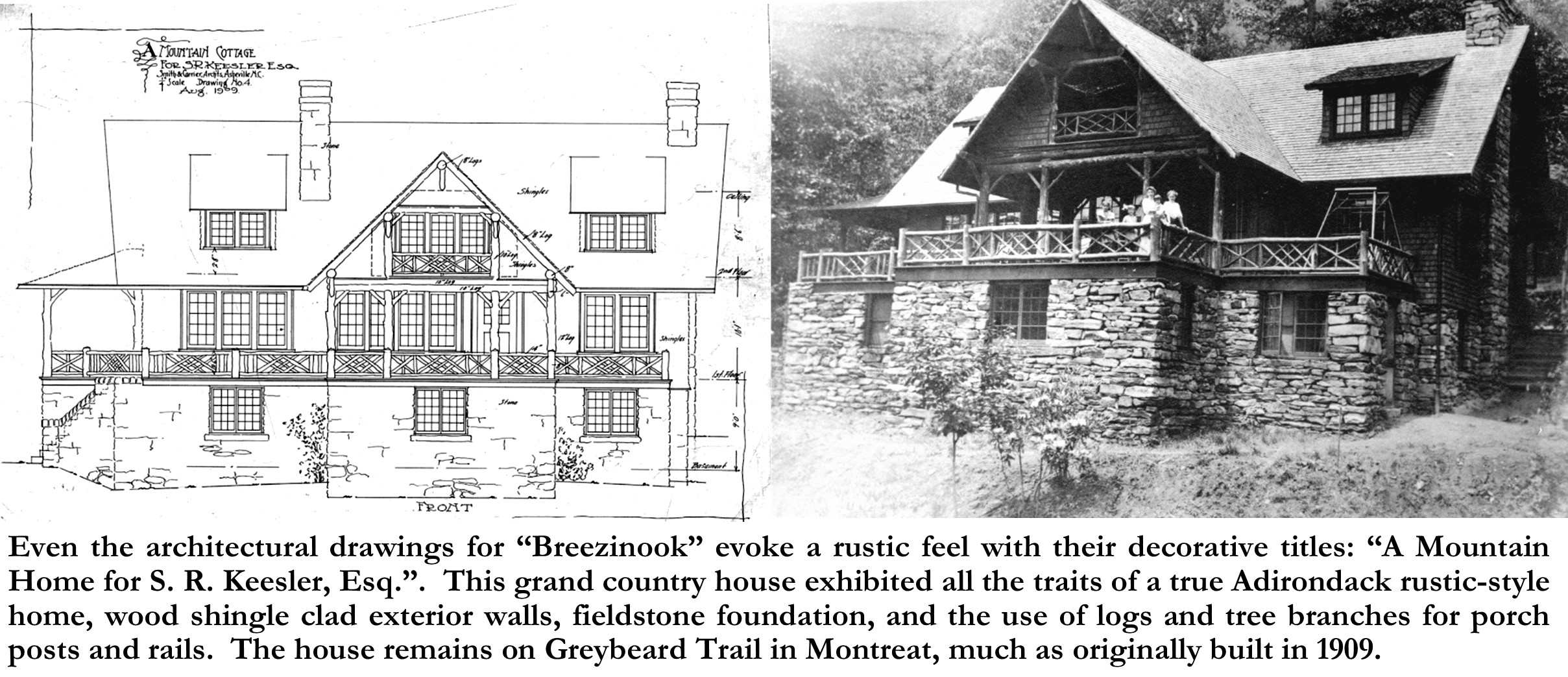

The Adirondack rustic-style continued to be a prevalent style used for Montreat cottages for the ensuing decades following the building of those early cottages. Perhaps the best example of this is the huge Ricard Sharp Smith design of a large rustic-styled “cottage”, called “Breezinook” built for Samuel R. Keesler in 1909, on Graybeard Trail. Even the architectural drawings evoke a rustic feel with their decorative titles: “A Mountain Home for S. R. Keesler, Esq.”. This grand country house exhibited all the traits of a true Adirondack rustic-style home, wood shingle clad exterior walls, fieldstone foundation, and the use of logs and tree branches for porch posts and rails. Perhaps the most unique and decorative rustic treatment was the second-floor balcony under the prominent large center front gable. Interestingly, “Breezinook” had simple shed-roofed dormers similar to those humble early cottages.

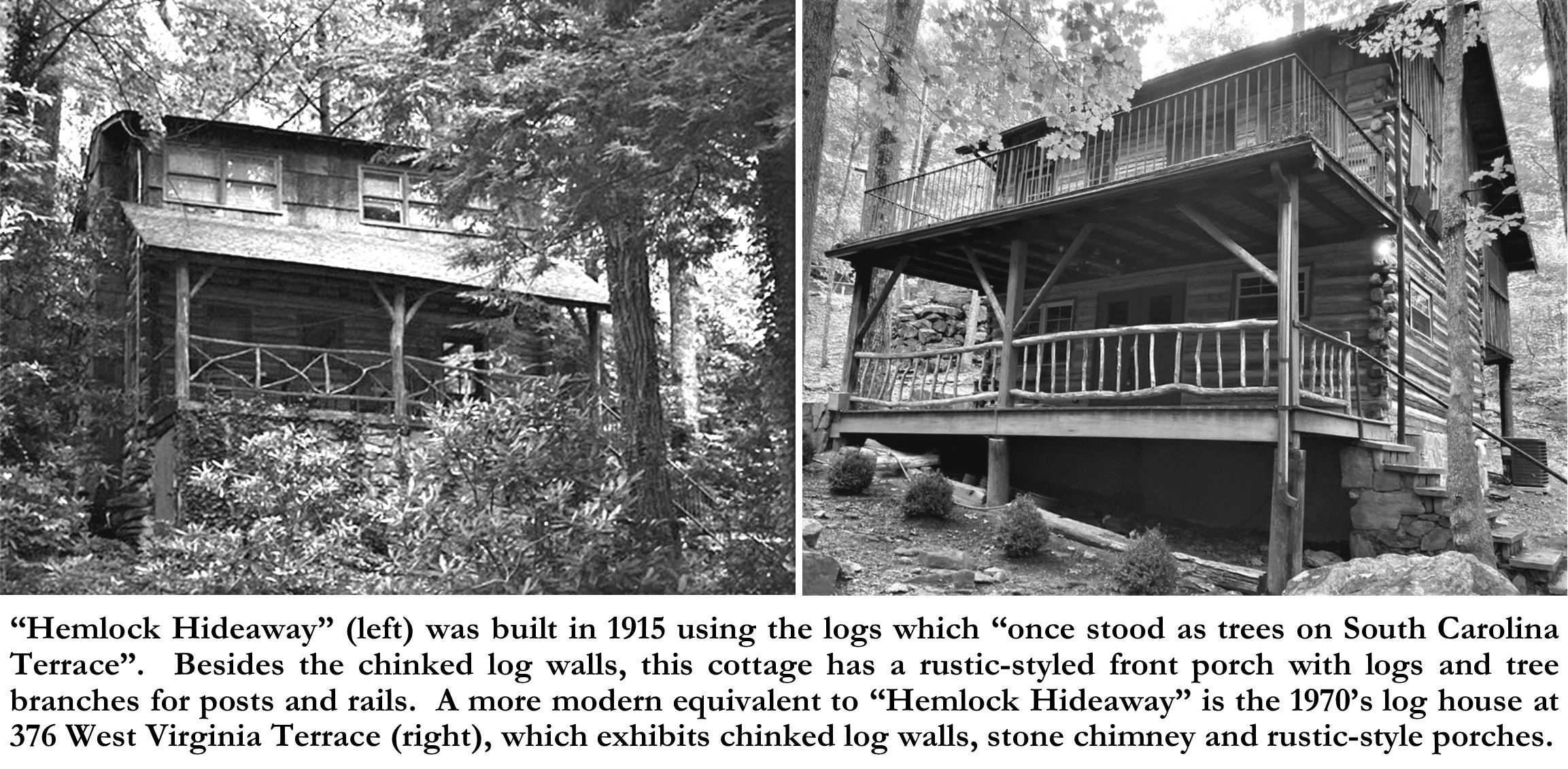

In 1915, Herbert & Pearl Love, upon the suggestion of MRA President R. C. Anderson, had a rustic-style log cabin built for them at 424 Kentucky Road. “Hemlock Hideaway” was reportedly built using the logs which “once stood as trees on South Carolina Terrace”.[55] Besides the chinked log walls, this cottage has a rustic-styled front porch with logs and tree branches for posts and rails. A more modern equivalent to “Hemlock Hideaway” is the 1970’s log house at 376 West Virginia Terrace, which exhibits chinked log walls, stone chimney and rustic-style porches.

The Adirondack Rustic-style at Montreat was not limited to the design of the cottages but also influenced the design of Assembly buildings and was even employed on numerous landscape features such as walkways, bridges, gazebos, and bridges. The first mention of the rustic-style was in 1897 when the New Haven, CT Morning Journal-Courier reported that New Haven architects Brown & Berger were designing a hotel for the new development at “Mountain Retreat, about fifteen miles from Asheville, N.C.”. The report went on to describe that “the hotel will be of rustic architecture, of logs and field stone, 34 x 154 feet, two stories high, with thirty sleeping rooms and fireplaces in each room; large office, dining room, etc.”. However, even though Frank Elwood Brown, the primary partner of Brown & Berger, resigned from the firm in 1898 to move to Montreat for his health, this rustic-style hotel was never built, and in fact when the Montreat hotel was finally built in 1899, the Association chose Asheville architect Richard Sharp Smith to design its hotel. The Smith-designed hotel was clad in pebbledash with Tudor-style timbering, certainly unlike the Brown & Berger proposed rustic-style hotel.

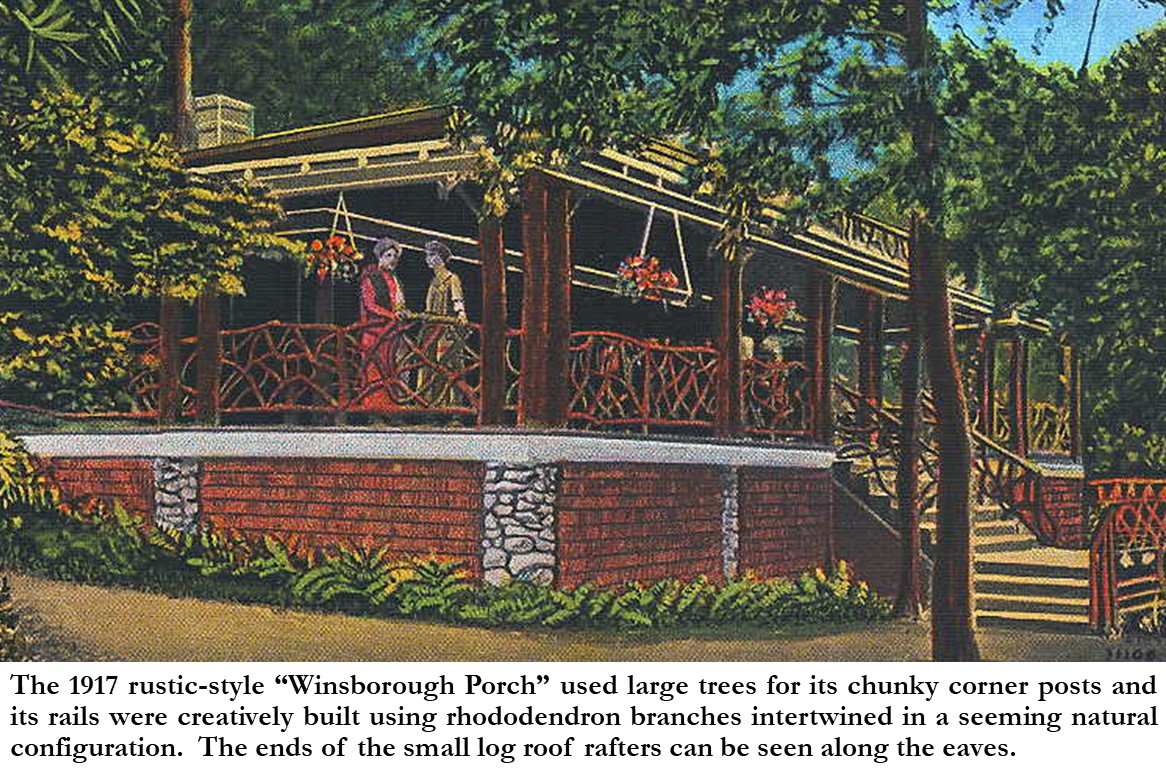

In 1917 the Winsborough Building was erected by the Woman’s Auxiliary of the Presbyterian Church for their own use on the Montreat campus as the social and business hub for the women’s activities. The simple frame building was most noted for its large rustic-style porch and was often just referred to as the “Winsborough Porch”. Large trees were used for the chunky corner posts and the rails were creatively built using rhododendron branches intertwined in a seeming natural configuration. In a vintage postcard photo of the porch, the ends of the small log roof rafters can be seen along the eaves. Unfortunately, this building and its rustic-style porch were demolished in the 1950’s and replaced with a modern masonry building.

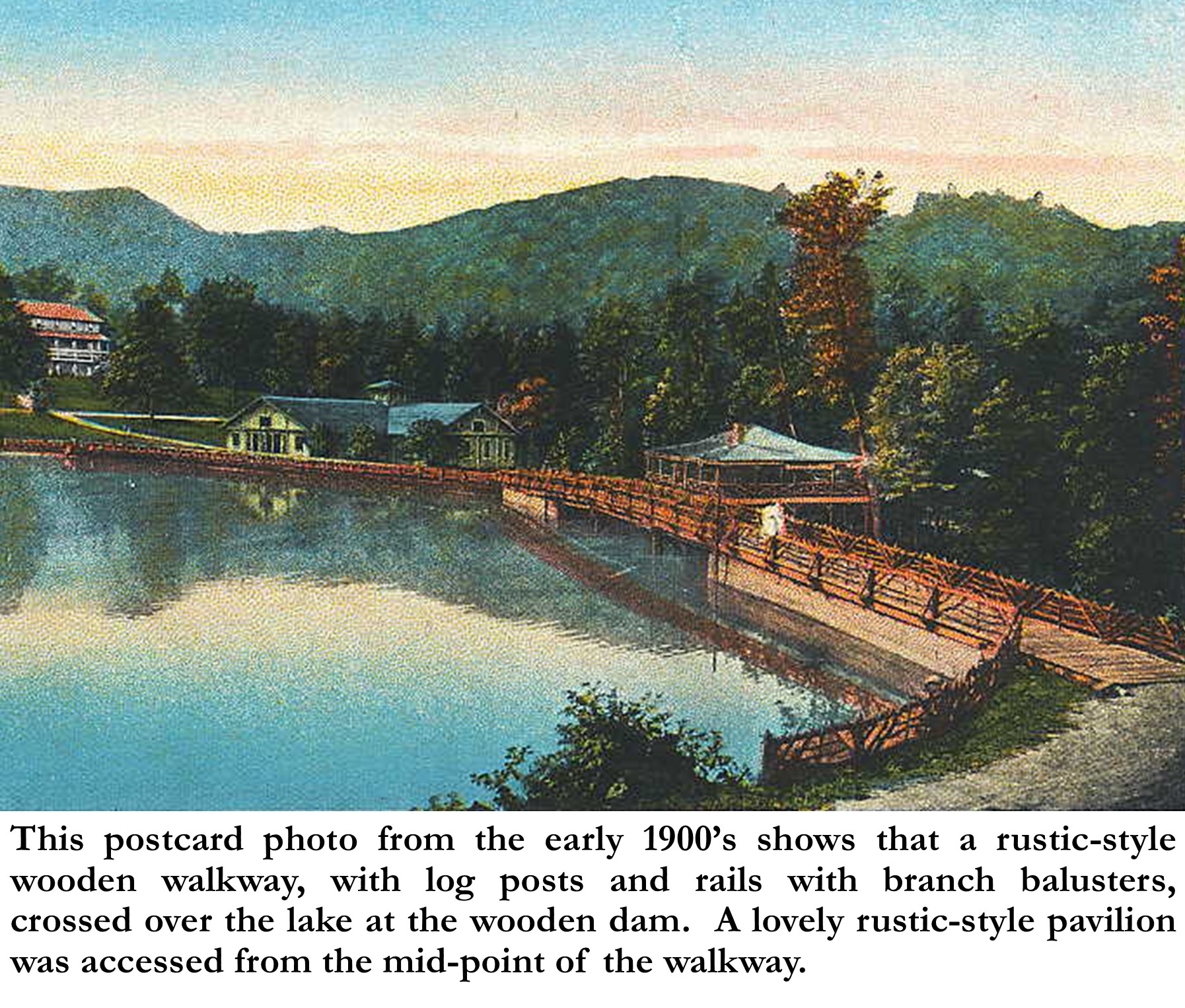

Another vintage postcard photo from the early 1900’s shows that a rustic-style wooden walkway, with log posts and rails with branch balusters, crossed over the lake at the wooden dam. A lovely rustic-style pavilion was accessed from the mid-point of the walkway. The walkway and probably the pavilion as well were demolished in 1924 to make way for a new concrete dam.

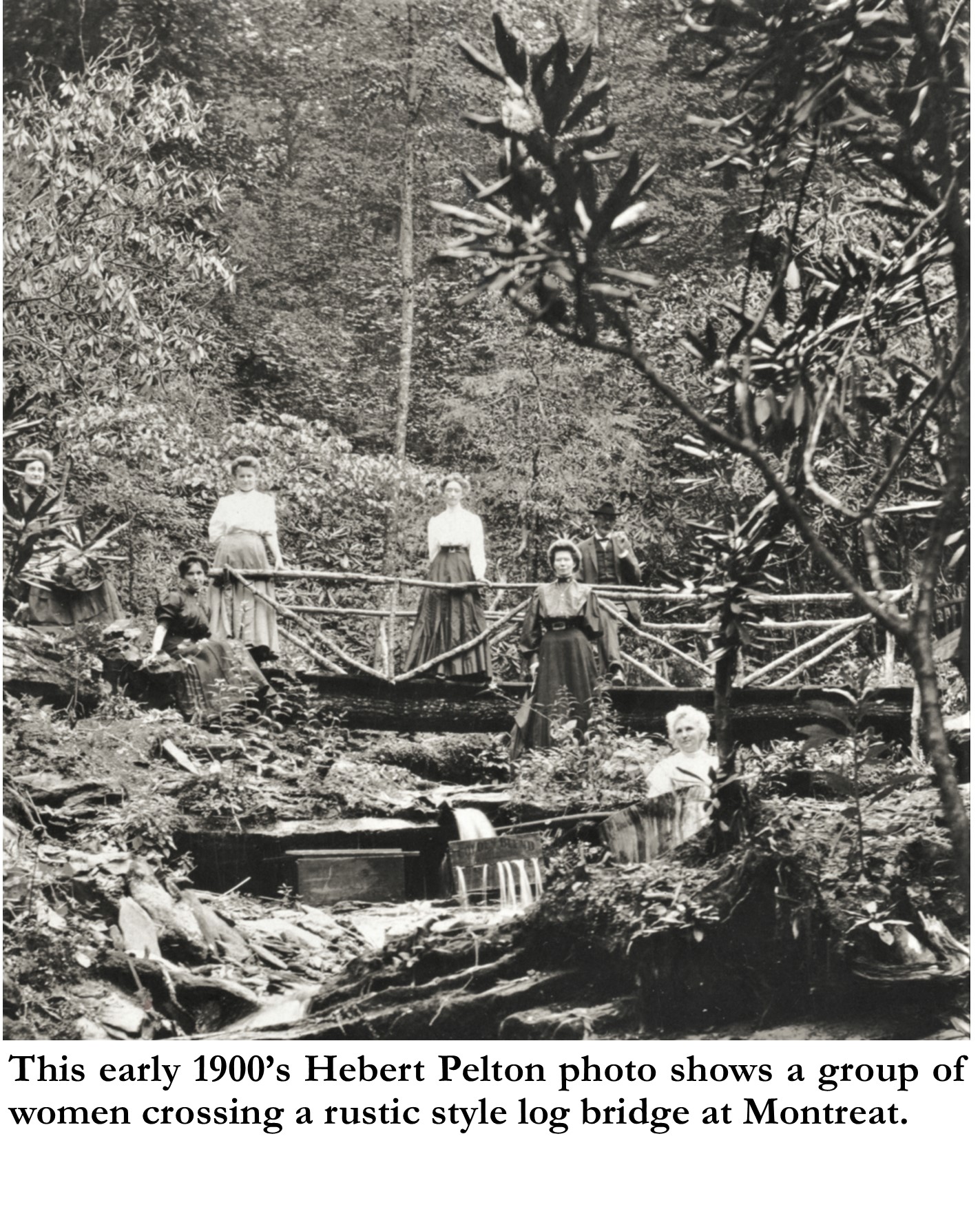

In one of Mary Martin’s letters home, she described a new bridge that was built over a stream in Montreat as made of a “large log with a log small log as a handrail”[56]. A vintage photo, from the early 1900’s taken by Asheville photographer Hebert Pelton shows a group of women crossing a rustic style log bridge at Montreat. The bridge looks just as Mary Martin had described, made of a large log (or logs) with small log handrails.

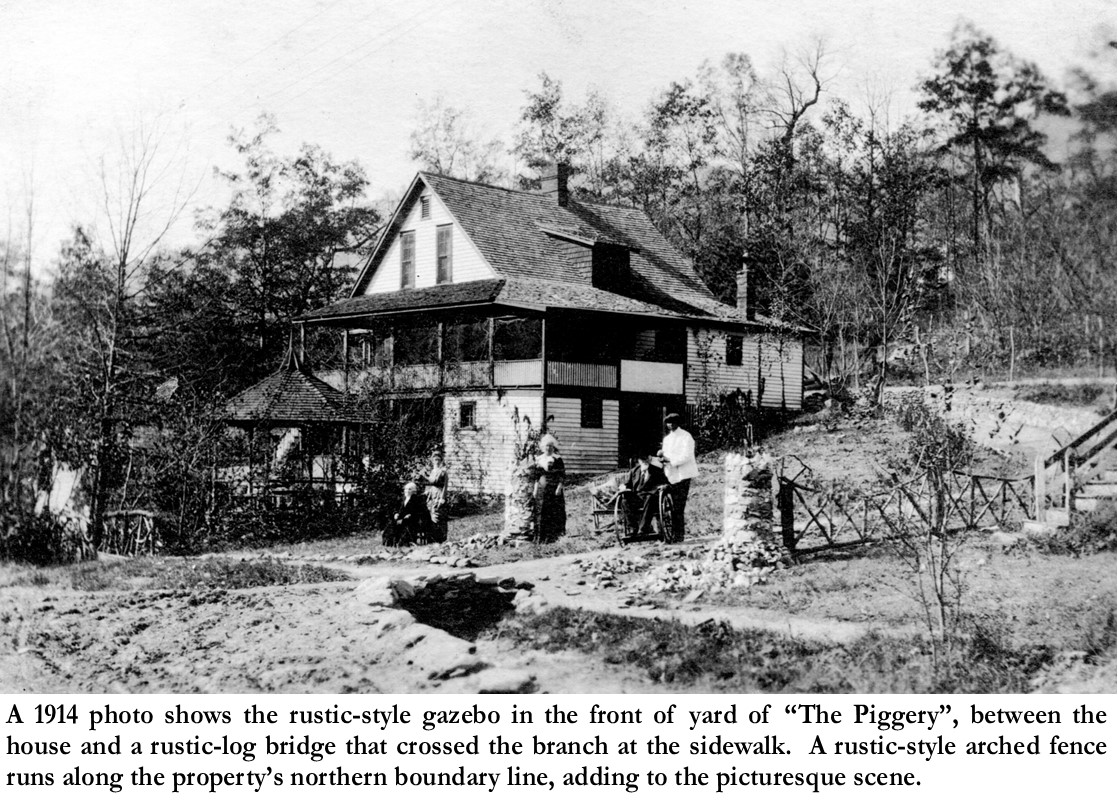

Scattered around Montreat during the early decades were several gazebos (also called “summer houses”), both around the Assembly area as well as in the yards of the cottagers. One notable example of a rustic-style gazebo sat in the front yard of the Cooper cottage, known as “The Piggery” along Assembly Drive. A 1914 photo shows the rustic-style gazebo in the front of yard between the house and a rustic-log bridge that crossed the branch at the sidewalk. A rustic-style arched fence runs along the property’s northern boundary line, adding to the picturesque scene.

In the first decades of the development of Montreat, the Adirondack-rustic-style design motif, which was used for the design of four of its earliest cottages, built between 1898 and 1899, dominated the design of its Assembly buildings, cottages, and landscape features, and though it is no longer prevalent, existing, and new examples of its use can often be spotted around the campus and village, contributing to the picturesque town that is Montreat.

Photo Credits:

1897 Assembly Site- Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Dr. Mary A. Holbrook, c. 1897– The Church at Home and Abroad. (1897). United States: Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.., page 314.

Nobby Island Sketches Montage– Image from page 151 of “Health and Pleasure on America’s Greatest Railroad”, by George H. Daniels, General Passenger Agent for the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad Co. (1890). https://ia802805.us.archive.org/3/items/healthpleasureo00newy/healthpleasureo00newy.pdf

Ocean Grove cottages– Margolies, John, photographer. Summer cottages, ocean pathway, Ocean Grove, New Jersey. New Jersey United States Ocean Grove, 2002. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017712289/-Caption by Dale Slusser.

Health & Pleasure Brochure– Image from Title page of “Health and Pleasure on America’s Greatest Railroad.” (1890).

William West Durant at Camp Pine Knot, Seneca, NY- Ray Stoddard, 1890., Caption by Dale Slusser. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_West_Durant_at_Camp_Pine_Knot.jpg

Dr. Holbrook’s House Front Façade, c. 1898– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Dr. Holbrook’s House Viewed from the Southeast, c. 1898– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Closeup of Green Cottage, “Hickory Lodge”, c. 1898– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Cropped and Captioned by Dale Slusser.

Photo of “Sillwood”, East Façade– photographed by Nancy Thomas Wofford of Greenville, SC & Montreat, NC., July 2021. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Photo of Cora Stone leaning on Dr. Holbrook’s gate, c. 1898– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Photo of Cora Stone’s Store/Library, c. 1898– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Photo of Cora Stone Cottage, “Grayrock”-– photographed by Nancy Thomas Wofford of Greenville, SC & Montreat, NC., July 2021. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Photo of Dr. Holbrook, Cora Stone, & Julia Gulick, on Holbrook steps, c. 1898– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Photo of Mary Martin, c. 1898– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Photo of Mary Martin cottage, “Chinquapin”, c. 1898– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Photo of Mary Martin cottage, “Chinquapin”, viewed from the northeast, c. 1910– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Closeup Photo of Mary Martin porch, “Chinquapin”, c. 1910– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Photo of living room of the Mary Martin cottage, “Chinquapin”, c. 1898– Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Photo of living room of “Chinquapin” – photographed by Nancy Thomas Wofford of Greenville, SC & Montreat, NC., July 2021. Caption by Dale Slusser.

Cropped Image of “Sleepy Hollow” at Nobby Island- Cropped from Image on page 151 of “Health and Pleasure on America’s Greatest Railroad”, by George H. Daniels, General Passenger Agent for the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad Co. (1890).

Stereoview of house & porch at Nobby Island-photographed by Alexander Carson McIntyre (1822-1897). https://tilife.org/BackIssues/Archive/tabid/393/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/652/Henry-R-Heath-Union-Soldier-Thousand-Islands-Pioneer-Part-II.html

Architectural Drawing of “Breezinook”– RS0967.6, A Mountain Cottage- S.R. Keesler- Montreat – Front, The Richard Sharp Smith Architectural Drawing Collection is owned by and housed at the Asheville Art Museum and was a gift of the Historic Resources Commission of Asheville and Buncombe County, copy from Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Photo of Front of “Breezinook”, c. 1910– collection of Sam Keesler Pratt, grandson of the Samuel R. Keesler builder of “Breezinook”.

“Hemlock Hideaway” Photo & 376 West Virginia Terrace house-both photos photographed by Nancy Thomas Wofford of Greenville, SC & Montreat, NC., July 2021. Caption by Dale Slusser.

“Winsborough Porch” Postcard Image– Collection of Mary McPhail Standaert & Joseph Standaert, used with permission.

Postacard Image of Walkway and Pavilion at Dam– Collection of Mary McPhail Standaert & Joseph Standaert, used with permission.

Pelton Photo of Rustic-bridge at Montreat– Image C145-5-Photograph by Herbert W. Pelton, C. 1912- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Photo of “The Piggery”, c. 1914– Collection of Mary McPhail Standaert & Joseph Standaert, used with permission.

[1] “Mountain Retreat Association to Go To Work At Once”, Asheville Citizen Times, Asheville, NC, June 2, 1897, page 1.

[2] The Asbury Journal 68/2:160-164, page 160.,© 2013 Asbury Theological Seminary.- https://place.asburyseminary.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1206&context=asburyjournal

[3] “God’s Brush Arbor: Camp Meeting Culture during the Second Great Awakening, 1800-1860”, by Dwayne Lyon.–A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, August, 2016.

[4] Chautauqua Movement History, The Colorado Chautauqua Historic Landmark- https://www.chautauqua.com/about-us/history/chautauqua-movement-history/

[5] The Chronicle, New Bern, NC, July 16, 1897, page 1.

[6] “What the Mountain Retreat Association Proposes to Do”, Asheville Citizen Times, Asheville, NC, June 3, 1897

[7] From “History” on Mount Holyoke website- https://www.mtholyoke.edu/about/history

[8] “American Board Archives”- http://dlir.org/arit-american-board-archives.html

[9] This information came from: “American Women Missionaries at Kobe College, 1873-1909: New Dimensions In Gender”, by Noriko Kawamura Ishio. AST Asia History, Politics, Sociology, Culture Edited by Edward Beauchamp University of Hawaii- A Routledge Series.-. https://epdf.pub/american-women-missionaries-at-kobe-college-1873-1909-east-asia-history-politics.html

[10] The Mount Holyoke, Volume 3, Number 9, June 1894, page 225. – “-’89. Cora A. Stone of the Girls School, Kobe, Japan has returned to this county on account of ill health, and is now at Roxbury, Mass. Dr. Mariana Holbrook (non-graduate, ’78) has accompanied her.”

[11] San Francisco Chronicle, September 27, 1896, page 33. [A report of missionaries returning from the Orient “on the next steamer”– “Rev. W. W. Curtis and family and Dr. Mary A. Holbrook are also to arrive.”

[12] Ibid.

[13] Asheville Citizen Times, September 6, 1898, page 2.

[14] “Black Mountain Assembly-Regular Programme Begun-Persons Present-Culinary”, Asheville Citizen Times, July 22, 1897, page 1.

[15] The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, NY. June 21, 1896, page 9.

[16] “Henry R. Heath: Union Soldier, Thousand Islands Pioneer (Part II)”, Written by Steven D. Glazer posted on March 13, 2011 22:32-on the “Thousands Island Life” website: https://tilife.org/BackIssues/Archive/tabid/393/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/652/Henry-R-Heath-Union-Soldier-Thousand-Islands-Pioneer-Part-II.html

[17] “History of Ocean Grove”- https://www.oceangrove.org/history

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Stick Style Houses by the Sea: The seaside town of Ocean Grove, New Jersey, is a picture-perfect catalog of Stick Style architecture.” By James C. Massey & Shirley Maxwell, dated Oct 19, 2012. – https://www.oldhouseonline.com/house-tours/stick-style-houses-by-the-sea/

[20] Great Camps of the Adirondacks, Revised and Enlarged Edition., by Harvey H. Kaiser, with editorial assistance by Ned Pratt. (Boston, MA: David R. Godine, 2020), page 12.

[21] Richard E. Morris (2018): The Victorian ‘Change of Air’ as medical and social construction, Journal of Tourism History, DOI: 10.1080/1755182X.2018.1425485- Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN, USA., page 1.

[22] Ibid., page 3.

[23] Health and Pleasure on America’s Greatest Railroad, by New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, 1890, page Co.https://archive.org/details/healthpleasureo00newy

[24] https://www.theadkx.org/exhibitions-events/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/natures-art/great-camps/

[25] Quoted from an unknown letter by Cora Stone-quoted in a record of the incorporation of the Cora A. Stone Memorial Library,Montreat, NC 1913. -from the Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections, 50 College Street, 8 Dwight Hall, South Hadley, MA, 01075

[26] Mother Pioneered At Montreat (Her Letters 1898-1899). Adaptation by Emilie Miller Vaughan; William Heidy, Jr. Editorial Assistant. (Originally published by Emilie Miller Vaughan, of Ithaca, NY, 1972) (This info. from a facsimile reprint by a bequest of Eugenie W. Love Estate, published by Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)- Department of History and Records Management Services, 1996), page 15. (Mary Martin first visited Montreat in the Spring 1898, shortly thereafter she moved permanently to Montreat and built her own cottage, Chinquapin (300 Georgia Avenue). In “Letter V”, dated November 22, 1898, Mary Martin writes: “We stayed at Dr. Holbrook’s last night and came up to our cottage today”.)

[27] Mother Pioneered At Montreat (Her Letters 1898-1899), Letter XXXI, June 4, 1899, page 51.

[28] Quoted from an unknown letter by Cora Stone-quoted in a record of the incorporation of the Cora A. Stone Memorial Library, Montreat, NC 1913. -from the Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections, 50 College Street, 8 Dwight Hall, South Hadley, MA, 01075

[29] Mother Pioneered At Montreat (Her Letters 1898-1899), Letter X, November 1898 page 20.

[30] “In The Mountains- These Are Happy Days Around Montreat”,The News and Observer, Raleigh, NC, August 4, 1901, page 13.

[31] Quoted from an undated handwritten autobiographical note by Cora A. Stone-from the Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections, 50 College Street, 8 Dwight Hall, South Hadley, MA, 01075

[32] Ibid, page 2-3.

[33] “A Tribute to Miss Stone, Founder of Cora A. Stone Memorial Library, Montreat, N.C.”, page 4.- from the Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections, 50 College Street, 8 Dwight Hall, South Hadley, MA, 01075

[34] Mother Pioneered At Montreat (Her Letters 1898-1899), Letter III, April 23, 1898 page 7.

[35] Ibid, pages 9-10.

[36] Mountain Retreat Association, Administrative Papers, John C. Collins & John S. Huyler 1897 – 1906, Box 27, Folder 12-Agreement (Typed and signed) and Exhibit A (handwritten)- Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC 28757

[37] “A Tribute to Miss Stone, Founder of Cora A. Stone Memorial Library, Montreat, N.C.”, page 4-5.- from the Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections, 50 College Street, 8 Dwight Hall, South Hadley, MA, 01075

[38] Perry Pictures Company was located in Malden, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston. Beginning in 1897, they produced rotogravure pictures on good quality stock paper, which could be ordered through their mail-order catalogs.

[39] “A Tribute to Miss Stone, Founder of Cora A. Stone Memorial Library, Montreat, N.C.”, page 5.- from the Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections, 50 College Street, 8 Dwight Hall, South Hadley, MA, 01075

[40] A handwritten account by Dr. Mary A. Holbrook, Montreat, N.C., c. 1904, page 2.- from the Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections, 50 College Street, 8 Dwight Hall, South Hadley, MA, 01075

[41] Ibid.

[42] “Montreat’s First Wedding”, Asheville Citizen Times, September 12, 1902, page 1.

[43] 10/29/1908 C. C. Lord, Guardian of Roderick Bruce Mackintosh to Abbie W. Kent LOT 124 BK 154 P 1 Db. 157/545.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[44] Mother Pioneered At Montreat (Her Letters 1898-1899), from excerpts of Janaury 1899 Letters, page 36-37.

[45] See the following deeds at the Buncombe County Register of Deeds: 07/22/1905 Mary A Holbrook to Abbie W. Kent POWER OF ATTY Db. 138/442.; 07/22/1905 Mary A Holbrook; Abby W Kent, w Power Attny to Alice W. Alden LEASE TRANSFER MONTREAT Db.140/14.

[46] “Death of a Former Resident: Miss Sarah Everett At The Age of Ninety Goes to Her Reward”, The Sutter County Farmer, Yuba City, CA, October 25, 1912, page 8.

[47] 05/11/1915 Abbie W Kent to Mountain Retreat Association LOT 124 BK 154 P 1 Db. 202/302.; 06/17/1915 Mountain Retreat Association to Mary Ransom & Lillie Ransom LOT 124 BK 154 P 1 Db. 192/226.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[48] Mother Pioneered At Montreat (Her Letters 1898-1899), Introduction, by Emilie Miller Vaughn, Ithaca, NY-March 30, 1972.

[49] Ibid, Letter IV, page 14.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Mother Pioneered At Montreat (Her Letters 1898-1899), from excerpts of December 1898 Letters, page 29.

[52] Ibid.

[53] The 1895 – 1902 Ledger/Register for Mountain Retreat shows: Henry Hodges Nutting is listed on alphabetic index page as having a record on page 320 (page 319 is struck through and was a mistake). On page 320, HH Nutting is shown buying a share/lot lease on June 18, 1898, for $52 with an initial cash payment of $12, leaving a balance of $40. No lot number was assigned. (all property was leased at this time). On August 30, 1898, the real estate transaction is listed as a default of the $40 balance.-Info from Ron Vinson, Executive Director: Presbyterian Heritage Center, Montreat, NC.

[54] Asheville Citizen Times, September 6, 1898, page 2.

[55] The First Chapter-Early Houses of Montreat: 1897-1917., by Henrietta Wilson and Bluford B. Hestir; Linda Patton Nance; and photographer E. Andy Andrews. Published by The Centennial year, Montreat, NC, 1997, page 52.

[56] Mother Pioneered At Montreat (Her Letters 1898-1899), from excerpts of May 1899 Letters, page 51.