By Dale Wayne Slusser

Asheville’s enduring architectural legacy began in the 1890’s with the building of the Biltmore House and estate. Asheville was a remote inaccessible mountain community until the railroad finally breached the treacherous terrain to begin service to the area in 1880. With the advent of the railroad combined with the fresh mountain air and scenic beauty, by 1890, Asheville was burgeoning as a destination “get-a-way” for the rich and famous of the Gilded Age. It’s most famous visitor was George W. Vanderbilt, who after numerous visits decided to settle here and build a “cottage” for himself. “Biltmore”, as he named his new house and estate soon rivaled any of his relatives’ “cottages”, even in Newport. Asheville’s architectural legacy and the “Biltmore-style” however does not stem from the house itself or even from its famous architect Richard Morris Hunt, rather from his little-known assistant, a young British immigrant named Richard Sharp Smith, who Hunt had sent to Asheville in 1890 to supervise the building of Biltmore House.

Born in Keighley, Yorkshire, England in 1852, Richard Sharp Smith immigrated to America in 1882, as a practicing architect. After a few stints in other architectural offices, he found employment in the New York City offices of Richard Morris Hunt. Smith’s providential appointment to supervisor of construction of the Biltmore House was life-changing for him and a boon to his career and to Asheville’s future built environment. As fate would have it, Smith forged a bond with George Vanderbilt, and with the death of Richard Morris Hunt in 1894, even before the opening of Biltmore House in 1895, Smith decided to make Asheville his permanent home.

Richard Sharp Smith’s primary contribution to Asheville’s architectural legacy was his signature “Biltmore-style”, with its blend of English Arts and Craft styling combined with Elizabethan Tudor and Old World influences. Though his style was similar to his American contemporaries like Wilson Eyre, Frank Furness, and Will Price, his British training (Kensington School of Art) brought a more English influence to his style. Though he would go on to design in various revival styles in the early twentieth-century, his “Biltmore-style” would become his true legacy to Asheville, especially to its residential fabric.

The “Biltmore-style” began when Smith was hired by Vanderbilt to design the homes, shops and auxiliary buildings for “Biltmore Village”, a picturesque development established by Vanderbilt to house the workers of his estate. Located just outside the “Lodge Gate” of the estate, the new “village”, laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted, had as its centerpiece, All Souls Episcopal Church. Upon Richard Morris Hunt’s death in 1894, the only buildings designed and built for the village, besides the church, was the train depot and Biltmore Estate Offices, Richard Sharp Smith designed the bulk of the remaining buildings. Soon a quaint yet bustling pseudo-English village began to appear in the mountains of Western North Carolina. The houses and shops with their charming hip roofs, truncated gables, Tudor timber-framing and pebbledash walls began a stylistic trend that influenced future local architects such as Charles N. Parker, W. H. Lord, and William Waldo Dodge, and even continues to influence Asheville’s architects of today.

Smith’s design for Cottage ‘H’ is a representative sample of what would become his signature “Biltmore-style”. The first floor with its three rooms, dining room, parlor, and kitchen were quite cozy and charming for a small family. The cottage appears to be one-story with its low-slung steep roof and truncated side gables, but in fact it has three small bedrooms tucked into its second story. Smith also designed numerous larger cottages for the supervisors, as well as the service buildings for the village such as the post office, retail shops, barber shop and even a fully-equipped hospital.

George Vanderbilt also commissioned Smith to design five large “Biltmore-style” cottages on nearby Vernon Hill overlooking the estate. With their picturesque names such as Spurwood, Westdale, Ridgelawn, Sunnicrest and Hillcote, they served as rental cottages for Vanderbilt’s affluent guests. Unfortunately, Sunnicrest is the only surviving cottage, but it has recently been restored to its former glory.

Smith’s “Biltmore-style” soon spilled over to other parts of Asheville, even before Biltmore Village was completed. While Vanderbilt was completing his building project, Asheville was beginning to expand its residential areas. Asheville’s new “electric train”, which was the first of its kind in the country (1889), allowed for expansion of new developments into outlying areas. One of those first neighborhoods established was “Montford”, northwest of center square. Smith designed many houses for Montford, and though a few were labeled “residence” on the building plans, most were labeled “cottage”. In Montford, Smith’s signature English-cottage styling was expanded to include wood shingles on the upper floors, varied roof lines and an occasional turret; however his signature pebble-dashed walls, steep roofs, truncated gables and 10″ square porch posts with simple brackets marked his homes. A few examples of his homes in Montford include the M. T. Brown Cottage, Dr. Charles Jordon residence, and the Frederick Rutledge Cottage, to name just a few. In fact, Montford has the greatest number of extant R. S. Smith designed homes, outside of Biltmore Village.

Sometime around 1905, Smith went into partnership with Albert Heath Carrier, a young engineer. In 1910 the firm incorporated as Smith & Carrier, and by the time of their dissolution upon the death of Smith in 1924, they had designed over 700 buildings. Although Smith is remembered best for his “Biltmore-style” residences, he not only designed in many other styles but he also was responsible for much of Asheville’s downtown commercial development during the early twentieth-century. His first downtown project was the design of the Young Men’s Institute, in 1892. The pebble-dashed building with its brick quoins not only resembles the Biltmore estate buildings, but was in fact commissioned by Vanderbilt for the many African-American workers in his hire.

Soon the list of downtown Smith-designed buildings included a number of hotels, medical buildings, office buildings, schools and even a monument (to former NC Governor, Zeb Vance). These masonry buildings were modern and up-to-date and many were “fire-proof”. In fact Smith was the first in this area to use “fire-proof” reinforced concrete construction. The names of these buildings sound like a litany of notable Asheville historic buildings: The Asheville Club (later remodeled as the Miles Building), The Legal Building, Elks Home, Masonic Temple, Haywood Building, Y.M.C.A., The Citizen Building, The Langren and The Loughran hotels.

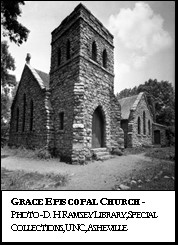

Churches were also part of Smith’s repertoire. Not only do most of them still survive today, but they are some of the most picturesque churches in the area. They include: A. M. E. Zion’s Hopkins Chapel on College Street; St. Mary’s Episcopal Chapel (Smith’s own church); and perhaps his largest, St. Lawrence Basilica, with its exquisite “Guastavino” tiles and vaulted dome. But my favorite is the charming stone Grace Episcopal Church on N. Merrimon Avenue. Smith’s British heritage shows in his design for Grace Church. With its cross-transept plan and small castellated tower entrance, it would feel just as comfortable sitting in any small rural village in England.

Following the success of Montford, other areas of Asheville began to be developed. E. W. Grove, a pharmaceutical magnate from St. Louis moved to Asheville in the late 1890’s. By 1903, Grove was investing his money in developing Asheville. He set his sights on the Northeast section at the end of Charlotte Street, surrounding his recently acquired Asheville Country Club and Golf Course. “Grove Park”, as he named his new development, catered to a higher class of homeowner. Richard Sharp Smith not only designed a beautiful stone sales office for Grove Park (now the offices of the Preservation Society), but he received a number of commissions for house designs in the new development. Smith’s Grove Park commissions resulted in his many of his grandest house designs. Though grand, many of them retained signature Smith details. Perhaps his most grand designs were for the Thomas Lawrence, the R. S. Howland and the Dr. Herbert Miles residences. The Lawrence and Howland residences with their hip roofs, brick bases and Tudor timbered upper floors are signature Smith. But Smith made a departure from his signature Tudor styling on the Miles residence. It has colonial detailing affixed to an arts & crafts styled home with a quirky triple-gabled undulating roof. Smith also designed residences in Grove Park for notables such as NC Governor Locke Craig and the renowned statesman, William Jennings Bryant.

Richard Sharp Smith passed away at the age of 72 in 1924. But his legacy continued with the work of his protégés. This was soon evident in the designs for homes in the “town” of Biltmore Forest, an exclusive development of the late 1920’s. “Biltmore Forest” was developed by leading Asheville businessmen in cooperation with Vanderbilt’s widow, who had sold to them a huge section of the Biltmore Estate for their model community. The first few homes built were designed by Smith protégé Charles N. Parker, and show Smith’s influence. Judge Junius Adams’ and Thomas Wadley Raoul’s houses were not only two of the first houses built in Biltmore Forest, but they were both designed by Parker in the Smith-inspired English- Tudor/Arts & Crafts style. The Adams residence has more Tudor leanings, but the Raoul residence has a more pronounced Smith-influenced style.

Richard Sharp Smith’s influence continues to this day, as evidenced by the designs for homes in Asheville’s current booming housing market. Although now considered “mountain-style”, these new homes continue the “Biltmore-style” with Richard Sharp Smith’s signature design motifs: hip roofs, truncated gables, Tudor timber-framing and pebbledash walls (although stone and/or wood shingles are more often used).