By Dale Wayne Slusser- January 9, 2024

The first two decades of the twentieth century have long been known as Asheville’s architectural heyday, when many of its most famous historic houses and buildings were designed and built. One of Asheville’s most famous buildings of that era, the gothic-inspired “Jackson Building”, Asheville’s first skyscraper, was designed in 1921 by Ronald Greene, a young architect from Michigan, who had first arrived in Asheville in 1916. Let’s explore a “tidbit” of Asheville and Western North Carolina’s architectural history, by exploring a “tidbit” of Ronald Greene’s architectural legacy, specifically, what was his background, and what brought him to Asheville? And what was his early impact on Western North Carolina’s built environment?

In 1870, Asheville’s population was 1,400 residents, by 1880, the year that the railroads arrived, it had almost doubled to just over 2,600 residents. By 1890, Asheville was already becoming a popular “health resort” and “summer resident” destination, mostly for the rich and famous, and so the population had grown to over 10,000 residents. But by 1900, just three decades later, Asheville’s population had grown to be over ten times greater than it had been in 1870, recording in at 14,695.[1] This rapid increase in population naturally resulted in a sizable building boom in Asheville, to meet the need for increased housing, schools, as well as for larger public and civic buildings.

In 1870, Asheville’s population was 1,400 residents, by 1880, the year that the railroads arrived, it had almost doubled to just over 2,600 residents. By 1890, Asheville was already becoming a popular “health resort” and “summer resident” destination, mostly for the rich and famous, and so the population had grown to over 10,000 residents. But by 1900, just three decades later, Asheville’s population had grown to be over ten times greater than it had been in 1870, recording in at 14,695.[1] This rapid increase in population naturally resulted in a sizable building boom in Asheville, to meet the need for increased housing, schools, as well as for larger public and civic buildings.

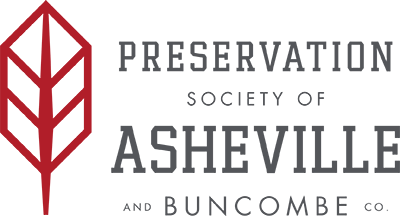

Fortunately for Asheville and Buncombe County, the building boom also attracted “a number of creative craftsmen trained in classic concepts”[2], who by the height of the boom, in the 1920’s, would form what local historian David Coleman Bailey termed, “the Architectural Corps” of Asheville. One of those “creative craftsman”, was a young architect, simply named Ronald Greene (he appears to have had no middle name or initial), who arrived in Asheville in 1916. Greene was born in Coldwater, Michigan on May 11, 1891, to Dr. Lymon and Jennie Green. It appears that Ronald Greene added the final ‘e’ to his surname, soon after living Coldwater, MI, as his parents’ and grandparents’ surname, as well as his own, are listed on the early censuses and city directories as “Green”. “Ronald Green”, at the age of 18, graduated from Coldwater High School in 1911.[3] Shortly, thereafter, Greene enrolled at the Pratt Institute in New York City. Pratt Institute was founded by businessman and philanthropist Charles Pratt, who envisioned a school for working-class people to get hands-on experience in industrial trades, arts, and engineering. The institute opened in 1887.[4] Ronald Greene graduated from Pratt Institute in June of 1913, with a certificate in Architectural Design, just a month after his 22nd birthday.[5] Greene’s obituary mentions that he “completed post graduate studies at Columbia University and Beaux Arts Atelier in Cleveland”.[6] I have not been able to find him in any Columbia University registers or alumni directories, however I suspect that his graduate work at Columbia was probably done in 1914 or 1915. And although I have yet to findthe “Beaux Arts Atelier in Cleveland”, I did find a Ronald Greene, listed as a draftsman, in a 1915 Cleveland City Directory.[7] It is most likely that Ronald was working as a draftsman in the “Beaux Arts Atelier”.

The Beaux Arts Atelier was a late-nineteenth and early twentieth century system of post-graduate architectural educational, to train artists and architects in the principles of Classical Art and Architecture.[8] The atelier system of architectural training in the United States was imported from the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts) in France, mainly by American architectural graduates of the École des Beaux-Arts. At the École, a student would join an “atelier” (French for “workshop”) or architectural studio, run by a practicing architect (called the “patron”), where the student would gain hands-on training and instruction, and working through the atelier, the student would enroll in the École’s curriculum, which consisted of a step-pyramid system “of lectures and “concours” (competitions). There were two kinds of concours: “esquisses” (sketches) and “projet rendres” (rendered projects)”.[9] To replicate this system in America, beginning in 1894, the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects was formed in New York City, by a group of Americans, all former students of the École. The Society of Beaux-Arts Architects developed standard architectural “programmes” for design problems to be given as assignments in architecture schools and in independent ateliers.[10] In order to further encourage young students to study the Beaux-Arts methodology, the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects initiated the prestigious Paris Prize in 1904, an annual competition open to Americans under twenty-seven years of age; the winner received admission to the Ecole without having to pass the standard entrance exam. In 1916, the Society, while continuing to function as a professional club, founded the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design. The modus operandi of both institutions “was the atelier (or studio) system, in which students were guided through the course of their training in the studio of a practicing architect. The basis of the program was a series of graded architectural competitions, treating different design problems, which became more difficult as one advanced. Students gained a certain number of credits at each level”.[11] We can assume that Ronald Greene received this type of training, perhaps at Columbia, but most certainly as part of the Beaux Arts Atelier in Cleveland.

Ronald Greene first arrived in Asheville in 1916, looking for work, or more likely to accept a position as an architect/engineer with the recently formed Carolina Wood Products Company. Carolina Wood Products Company’s origins had begun the year before, in 1915, as the Graham County Lumber Company. In February of 1915, the Asheville Times, quoting the Andrews Sun, reported that:

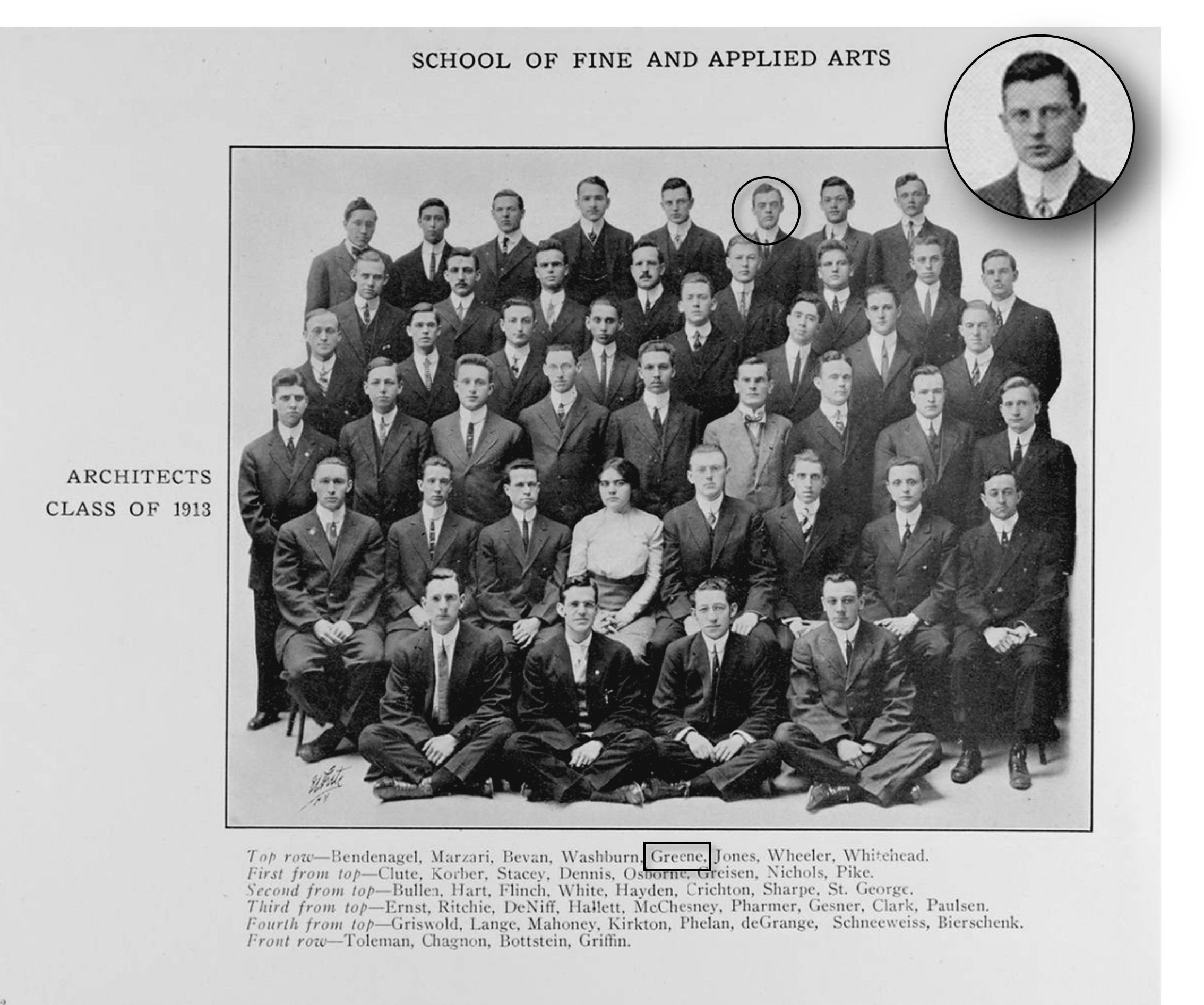

“The Graham County Lumber Co., Col. Frank Buell, president, has purchased about 30 acres of land, adjoining the property of the North Carolina Tanning Extract Co., and will erect thereon a large woodworking plant, which will use over ten million feet of lumber annually, mostly low grade chestnut oak and other hardwoods.”

“In this immense plant which will be equipped with up-to-date machinery, the lumber will be kiln dried, and then cut up into table tops and other furniture dimension stock, also made into house trim, and a specialty will be made of “cares,” that is the small pieces will be glued together and made ready to be veneered onto later by furniture manufacturers.”[12]

An earlier announcement clarified that the Graham County Lumber Company’s new purchase had included the former Andrews Lumber Company[13], and that its new woodworking plant was to be an expansion of the former Andrews Lumber Company’s former facility. The Graham County Lumber Company had been formed just a few years earlier by Col. Frank Buell and other associates from Bay City, Michigan, to timber lands and make lumber from the standing timber lands of “the Whittings of Graham County”, and to add to their timbering and lumber operations, in 1914 they had purchased the Cherokee Tanning Extract Company in Andrews, NC (in Franklin County, thirty miles southwest of Graham County), renaming it the North Carolina Tanning Extract Company[14]

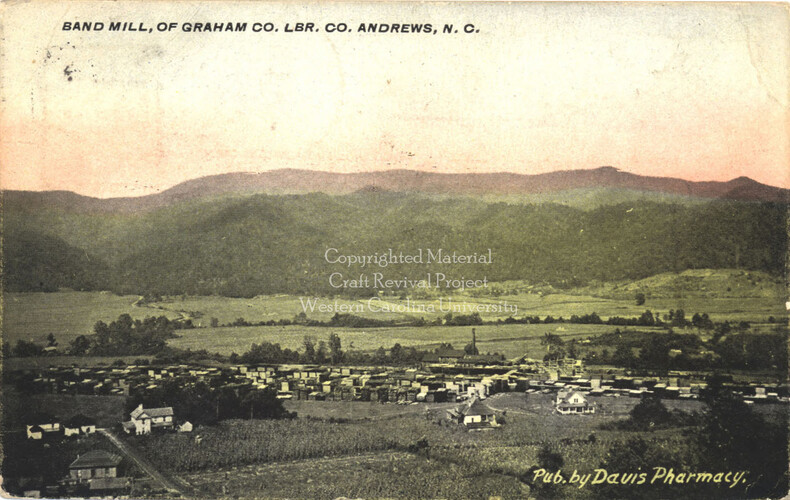

On October 22, 1915, the Asheville Citizen-Times, in a front-page article, broke the news of what it sensationally dubbed, “one of the largest developments in the history of Western North Carolina and one of the greatest industrial development projects in the life of Asheville”[15]. It was reported that the Graham County Lumber Company, in addition to and in conjunction with their vast timber tract holdings and other operations in Western North Carolina, had purchased out of receivership, the former American Furniture Manufacturing Company plant along the French Broad River in Woodfin, northeast corner of Asheville. Much to-do was made of the fact that this intentional deal was brokered by F. M. Weaver, who not only was the Receiver for the American Furniture Manufacturing Company, but also represented the Asheville Board of Trade, as chairman of its “industrial development committee”.[16]

Although it was sensationalized a bit, this was a massive undertaking. The plan was that the company would send the dressed lumber from its other operations scattered across Western North Carolina, to the new plant in Asheville “for development into furniture, houses, interior trim, and other products of a modern furniture factory and lumber yard”.[17] It was further announced that although the new plant to remain owned and operated by the Graham County Lumber Company, that “a new name will be chosen for the Asheville factory”.[18] Three months later, on January 24, 1916, the Asheville Citizen Times made the following announcement:

Starting this morning, the furniture factory and plant for the manufacture of ready-cut houses on the French Broad River will doing business under the new name of the Carolina Wood Products Company. The corporation was chartered under the laws of the state of Maine on January 10.[19]

The new plant of the Carolina Wood Products Company, which was on the west side of Riverside Drive (site now addressed as 950 Riverside Drive), just past the intersection of Old Burnsville Road, opened in January 1916 with a huge agenda of production. The plant would produce furniture, dimensional lumber, millwork and sash work and “ready-cut houses”! And to add to the complexity of the company’s make-up, the Carolina Wood Products Company, also functioned as contractors, taking on sizeable construction projects, sometimes acting as a design/build firm, furnishing architectural design and construction services.

Although it’s unclear whether Ronald Greene came to Asheville in 1916 to specifically accept the position with Carolina Wood Products, or whether he came to Asheville looking for work, and then found the job, either way, we know that Greene was working for Carolina Wood Products by the Spring of 1916. In April of 1916, Greene’s name was on a series of Carolina Wood Products Company advertisements, such as this one from the New York Times:

DRAUGHTSMAN WANTED- Capable of developing house plans from sketches and making good tracing; advise whether three months’ would be considered. R. Greene, Carolina Wood Products Co., Asheville, N. C.

The above-mentioned advertisement not only confirms when Ronald Greene began working for the Carolina Wood Products Company, but it also gives us a glimpse into the young 25-year old’s position as “Chief Architect” for the company. Clearly, Greene was acting as an architect, drawing sketches (preliminary design/concept sketches) for “house plans”, and then handing the sketches off to “draughtsmen” to develop into detailed “working drawings” used for construction. Greene appears to have been the chief architect of the company’s “ready-cut” houses.

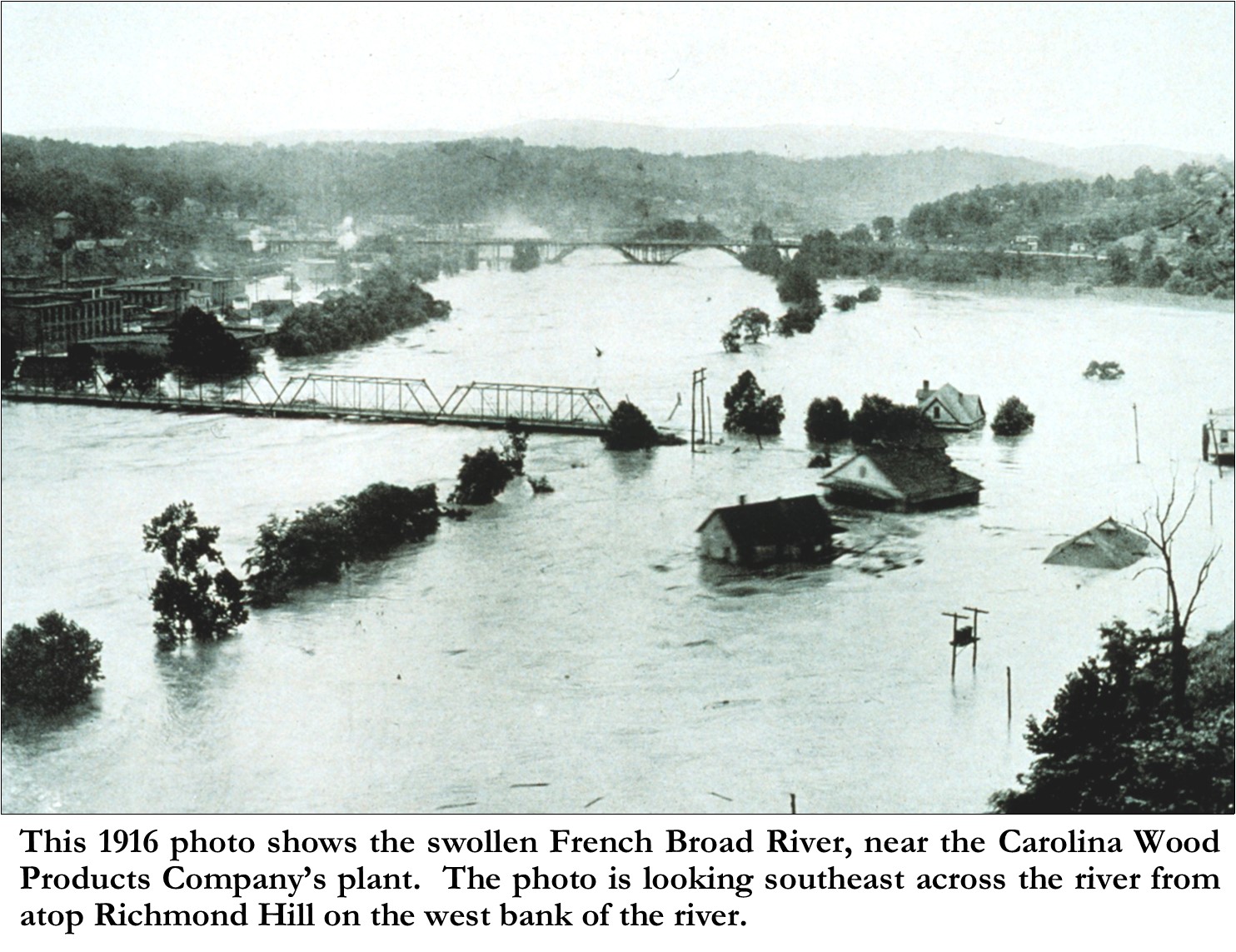

Just a few months after the Carolina Wood Products Company began operation, in July of 1916, disaster struck! Within a week-long period in July of 1916, two back-to-back hurricanes dropped a record-breaking 15-22 inches of rain (just in one 24-hour period) over western North Carolina, leaving most of the region’s riverways overflowing and ground saturated to capacity. On the morning of July 16th, although the rain had stopped and the sun was shining, the Swannanoa River and the French Broad River began to rise rapidly. The French Broad River swelled to 18.6 feet just before the river gauge and the bridge it was installed on were washed away. The French Broad River finally “crested at 23.1 feet and had a peak flow of 110,000 cubic feet per second—close to seven times its average annual peak streamflow”.[20] The average width of the French Broad, near Asheville, before the flood was 381 feet, but during the flood it spread to approximately 1,300 feet across. Of course, like many of Asheville’s industries which then lined the banks of the French Broad River, the Carolina Wood Products plant suffered tremendous losses. Estimated to be over $50,000 of losses, the damage to the plant was reported as: “One of the largest smokestacks of this new plant has gone, the boiler rooms were flooded, and the mill buildings swept by the flood. Lumber was washed away and the machinery so badly damaged that it will be two months before the plant can be placed on a working basis.”[21]

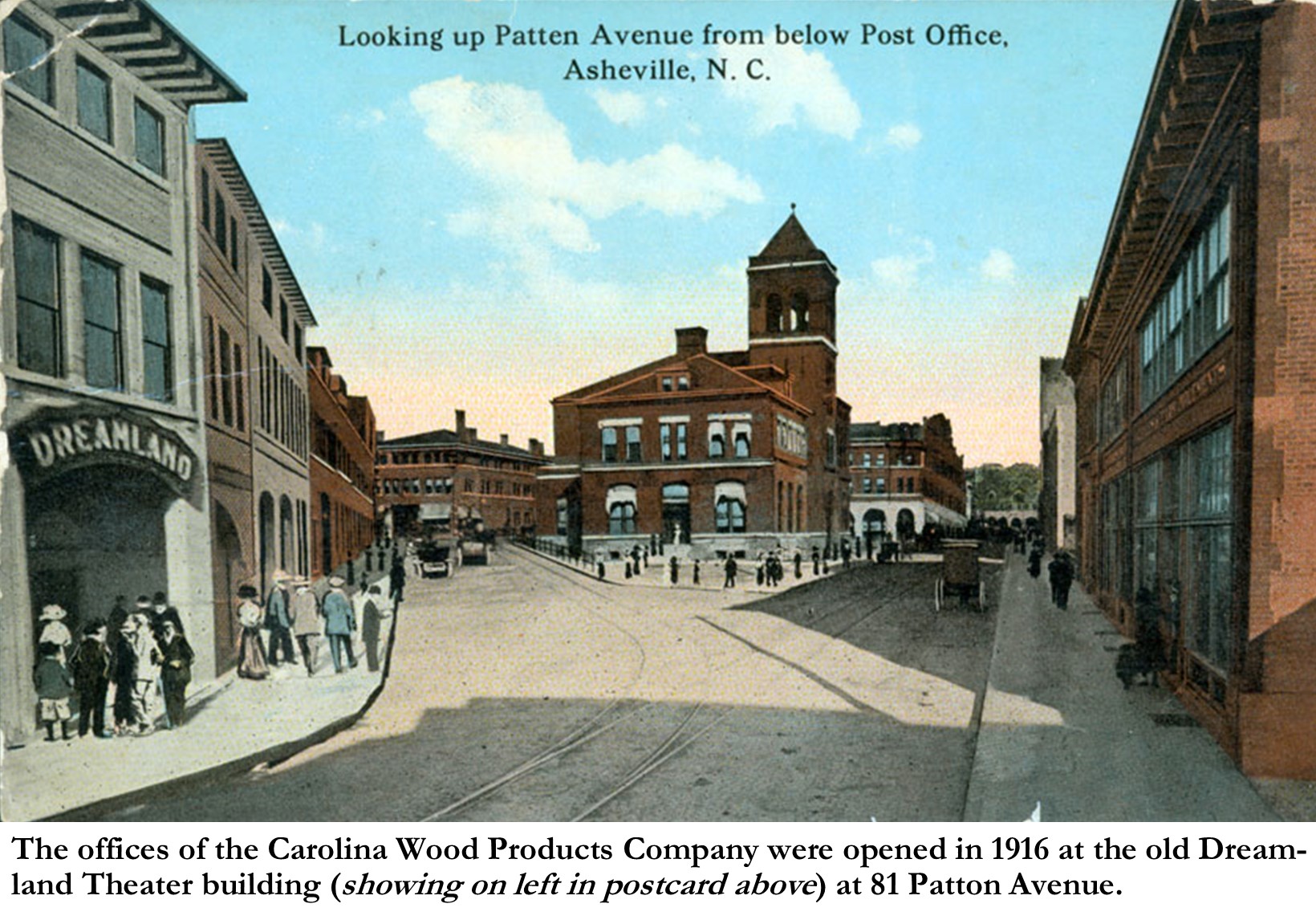

Production was soon restored at the Carolina Wood Products plant by September of 1916, when reporter Eugene Jones interviewed the staff and made a full report of this “industrial enterprise”.[22] Jacobs first interviewed the staff at their offices in the “remodeled Dreamland Theatre building on the corner of Patton avenue and Government Street” (now addressed as 81 Patton Avenue, across from Pritchard Park). Jones reported that the plant at Woodfin was then under the management of Elliot G. Stevenson of Michigan as president, with David Morgan as vice-president and general manager, and employed “300 operatives to run the factory and 35 to handle the business in the city offices”.[23] I suspect that Ronald Greene and his architectural draftsman worked in the “city offices”.

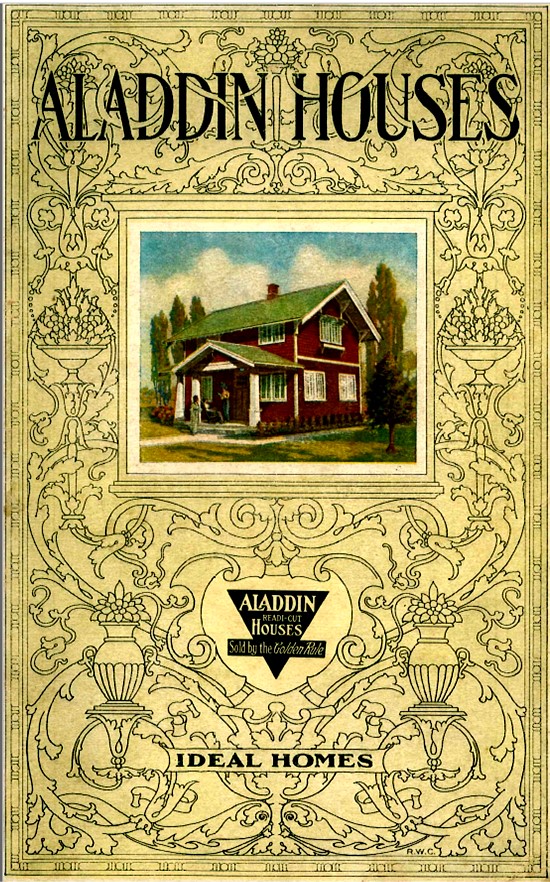

It’s unclear if Ronald Greene was connected with the Carolina Wood Products’ designs of its “ready-cut” houses or not. In December of 1915 (probably before Greene arrived in Asheville), Frank Buell, the company’s president, met with Asheville’s Board of Trade where he offered to develop a plan for and manufacture a ready-cut house, to be named the “Asheville”, from any plan or picture of an attractive house that the Board would select.[24] Buell further informed the board that its selection would be featured in the company’s catalogue of “houses of various types”, many of which Buell proposed to give local names, such as, “Pisgah”, “Mitchell”, “Swannanoa”, and “etc.”.[25] Unfortunately, I have not been able to find any catalog or document showing these houses. But apparently, they were to be manufactured as “ready-cut” house kits, such as those being marketed by such companies as Sears & Roebuck, Montgomery Ward, and Aladdin Homes. In fact, in January of 1916, Buell recruited two men, Charles Porter and Davidson Young of the North American Construction Company of Bay City, Michigan, which was the parent company for “Aladdin Homes”, to work for the Carolina Wood Products Company. [26]

Ronald Greene as chief architect/engineer for the company was most likely heavily involved in the construction projects that Carolina Wood Products Company contracted during the years 1916-1918. Although it is not totally clear, from all the evidence it appears that the company acted as a design/build firm, rather than solely a construction firm. Determining who the architect was for many of the Carolina Wood Products Company projects, proves to be difficult, as the company, though acting as a construction company, also had its own “architectural department” providing architectural and engineering services. Case in point is the company’s first major contract, which was for the building of the new Kenilworth Inn, which was being built to replace the old Kenilworth Inn which had been destroyed by fire in 1909. In September of 1916, in a lengthy article, it was reported that Carolina Wood Products Company had just signed the contract with Jake M. Childs (Kenilworth Park and Inn developer) “for the erection of the new Kenilworth Inn”.[27] And it was further[28] reported that “The plans and specifications for the new hotel have been completed by Charles Parker, who spent several weeks in preparing them”. However, just a few months later, in November 1916, as the project began, a reporter interviewed E. A. Fonda, whose position was as “House Manager” for the Carolina Wood Products Company. It was reported by the interviewer:

The question was asked Mr. Fonda if he could give the public some idea of the plans of the Kenilworth Inn which the Carolina Wood Products company was to build for the Kenilworth Hotel company, to which he said: “The hotel, which is strictly English architecture, has been designed and planned throughout in the architectural department of the Carolina Wood Products company, with the assistance of Mr. Donaldson, of the architectural firm of Donaldson and Meir, of Detroit, Mich., acting in the capacity of consulting architect.

Did the interviewer ask Fonda this question because he had been the reporter for the September article and knew that local architect Charles Parker had already drawn up the plans for the new hotel? Had the interviewer/reporter heard contrary rumors? My suspicion is that acting as a design/build firm, Carolina Wood Products decided to provide their own plans-but why? Were Charles Parker’s plan not detailed enough, or were there significant changes made to Parker’s design that necessitated a new set of drawings? Why also did the company need “Mr. Donaldson” as consulting architect? My guess on that is that Ronald Greene, who was the company’s “Chief architect” was not yet licensed to practice architecture, and so needed Donaldson to sign-off and “seal” the drawings. The only thing that we can conclude from this is that it is highly probable that Ronald Greene could have been involved in the design, or at least in the preparing of the construction drawings. And in fact, six years later, in 1922, when Ronald Greene (then out on his own with his own firm) was hired to draw up remodeling plans for the Kenilworth Inn, which was then being used as a government military hospital, his contribution was reported. It was reported that: “Ronald Greene, Architect, who drew the original plans for the erection of the Kenilworth Inn, is busy at work on plans for remodeling the property … [SIC]”[29]. Before it was even finished, in 1917 the Kenilworth Inn was commandeered by the U. S. War Department to be used as a military hospital. So, it first opened as a military hospital, THEN it became an Inn, then a hospital again for many years, but now it functions as a boutique apartment house.

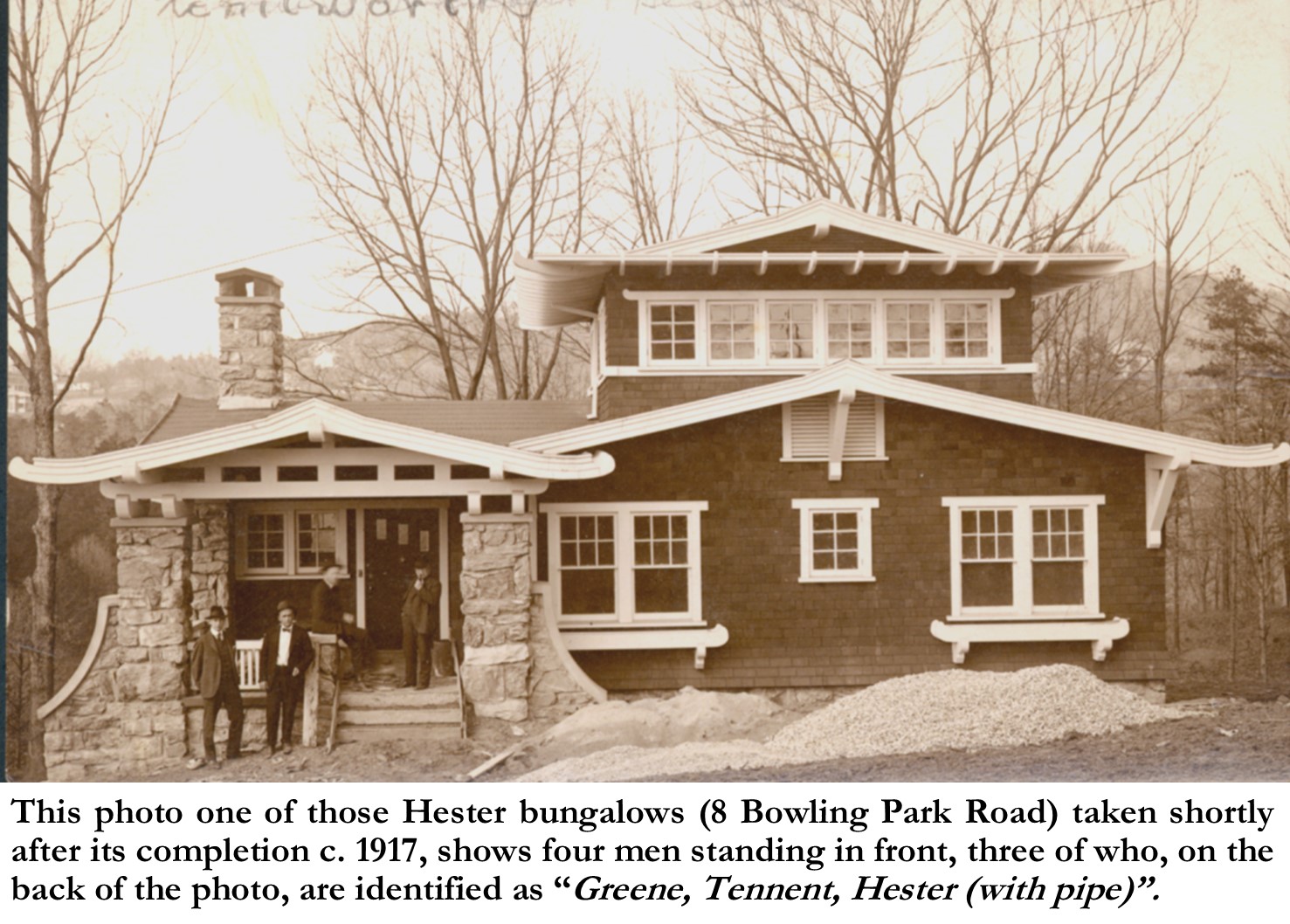

In conjunction with, though separate from, the contract to erect the new Kenilworth Inn, the Carolina Wood Products Company had contracted with E. G. Hester (another Kenilworth Park developer) to erect six cottages for Hester, and it was further reported that they had also contracted “with the Kenilworth Development company, and other property holders for the designing and building, within the next ten months of fifty high grade residences located on some of Kenilworth’s most scenic sites”.[30] Though we can’t confirm all of the fifty houses the Carolina Wood Products Company may have built in Kenilworth, we do know that indeed they did build at least five houses for Hester. Earlier, in July 1916, in was reported that the company was building five “California bungalows” for Hester. Interestingly, it was further reported that the bungalows had been designed by “E. A. Fonda of Florida, a recognized expert in the designing of this type, who is now connected with the Carolina Wood Products company”, and that “Mr. Fonda is personally superintending the construction of Mr. Hester’s bungalows”.[31] Was that correct that Fonda had designed those bungalows? How much of their design was done by Carolina Wood Products Company’s architectural department, and if so, was Ronald Greene involved in any way? Although I cannot sufficiently answer those questions, I can only add that interestingly, two photos of one of those Hester bungalows (8 Bowling Park Road) taken shortly after its completion, shows four men standing in front, three of who, on the back of the photo, are identified as “Greene, Tennent, Hester (with pipe)”.[32] Was Fonda the fourth man? But more poignantly, was Ronald Greene in the photo because he had designed the bungalow, or at least as “Chief architect” for the company, had he been involved in the production of detailed construction drawings? The Hester bungalows were built in front of the new Kenilworth Inn, along Bowling Park Road (4, 6, & * Bowling Park Road) and Caledonia Road (61 & 63 Caledonia Road) and are lovingly maintained by their owners and contribute to the historic Kenilworth neighborhood.

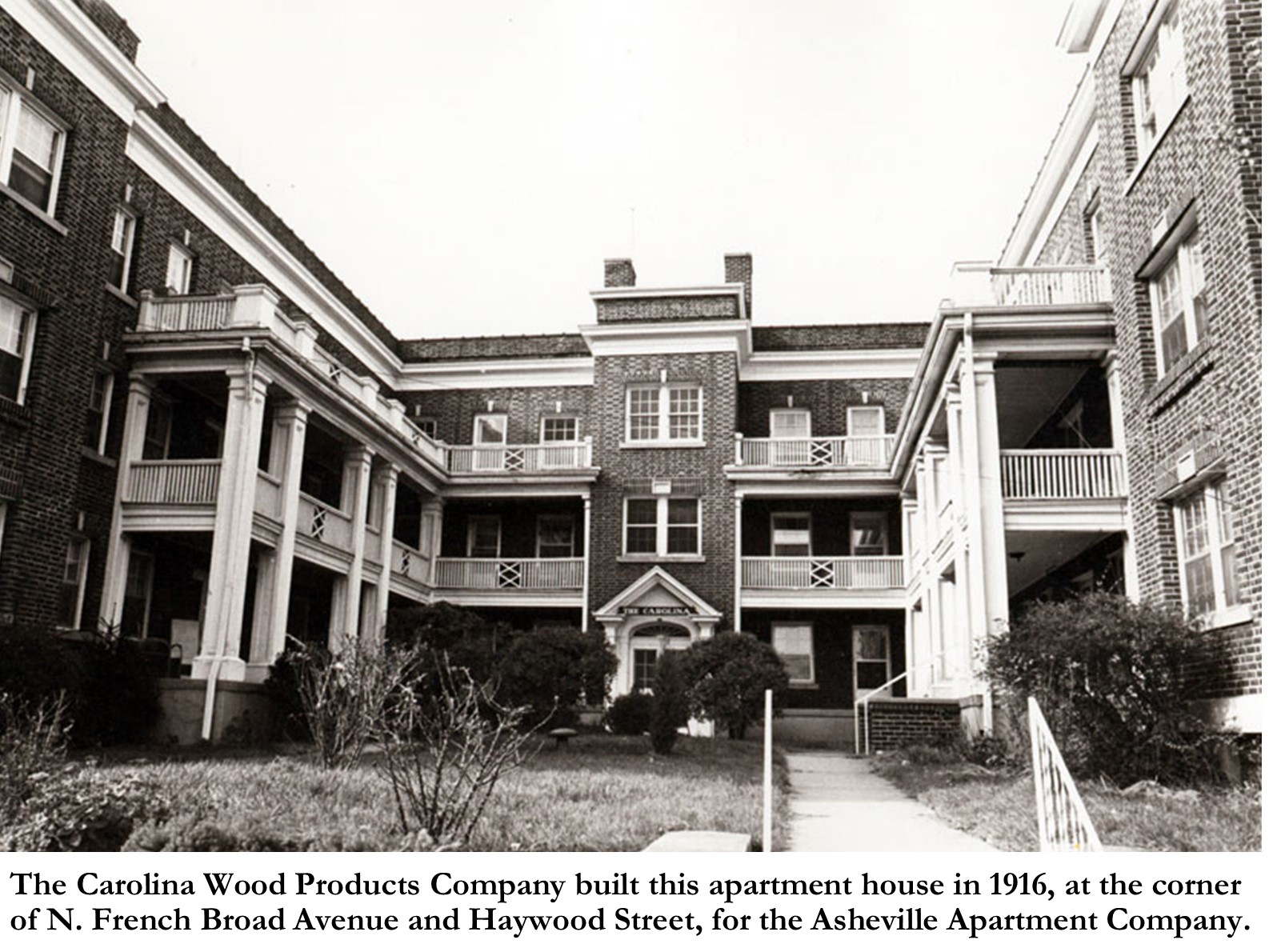

Ronald Greene and his “architectural department” at the Carolina Wood Products Company were extremely busy that first year, 1916. In addition to taking on the job to design and build the Kenilworth Inn and the Hester bungalows, the company had also contracted several other major projects. One such project was the contract to design and build a two-story apartment house for the Asheville Apartment Company. The contract was to design and build a four-story (three stories with a basement) brick apartment house at the corner of N. French Broad Avenue and Haywood Street. The apartment house was to have six apartments on each of its three stories, with laundry and storage facilities in the basement. E. A. Fonda, in the same interview previously mentioned, described the style of the new apartment house as “typical of the modern New York City fashionable apartment house”.[33] Built in a U-configuration, all the apartments faced a center entrance courtyard, and many of them had accompanying porches. The actual “style” used to design the building was the Colonial Georgia style connoted by its brick facades, sash windows, jack-arched window heads, and the Chippendale detailing on its porches. Again, to add to the confusion of who designed the buildings that were contracted to the Carolina Wood Products Company, a listing in the November 30, 1916 edition of the Manufacturers Record, credits the new Apartment house to architect “J. M. McMichael” of Charlotte, NC.[34] Although Greene was not given the credit for designing the building at the time (probably because he was considered part of the corporate Carolina Wood Products Company), he himself later confirmed that he indeed was the “chief architect” of the building.

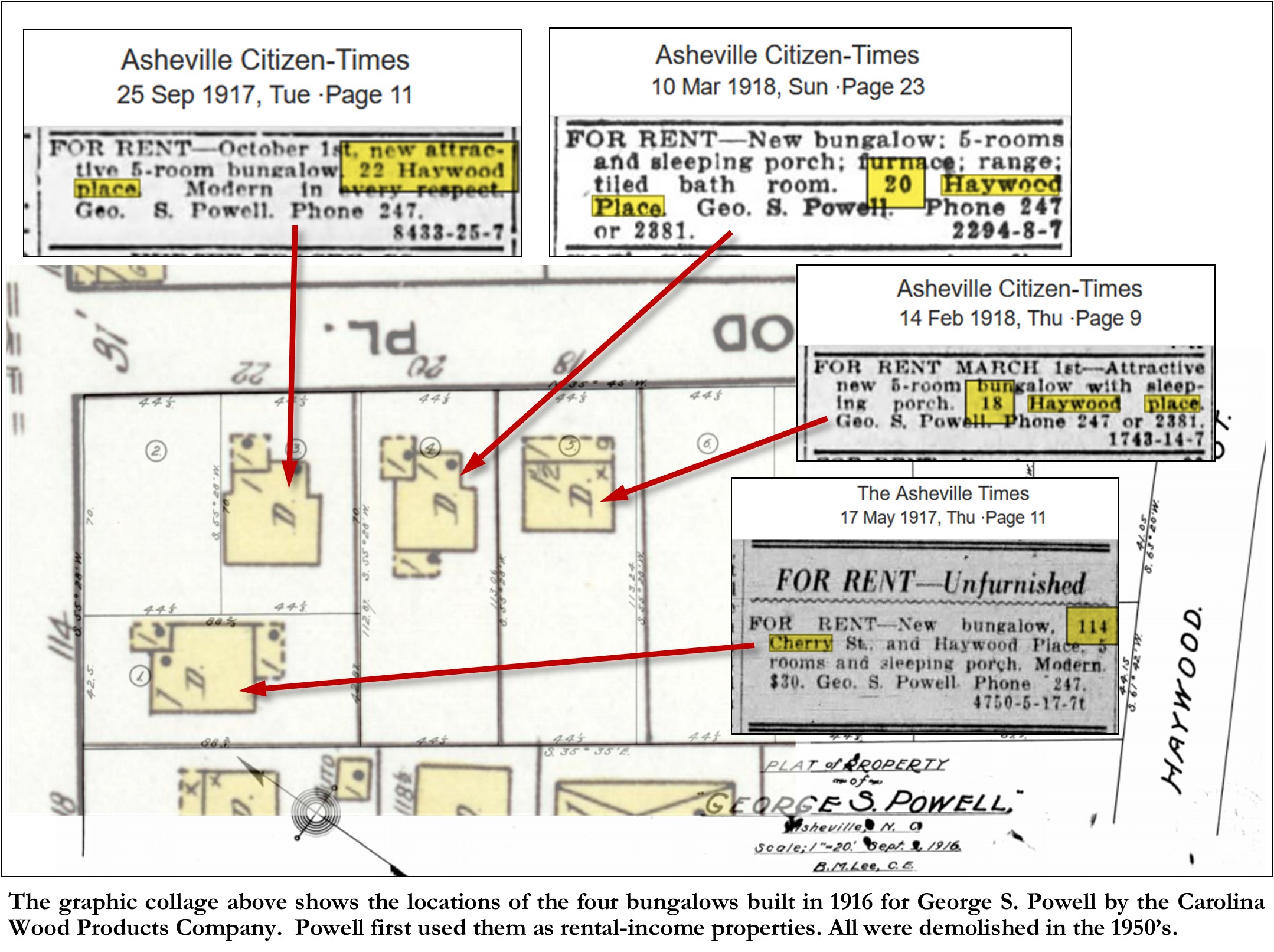

A relatively small project that Carolina Wood Products Company also took on in 1916, was the contract to design and build “four modern bungalows at the corner of Cherry and Cumberland, for George S. Powell”.[35] Technically these were built on the southwest corner of Cherry Street and Haywood Place (an extension of Cumberland Avenue). Unfortunately, the four bungalows were destroyed in the 1950’s as they were in the middle of the right-of-way for the new “Crosstown Expressway”, which became I-240.

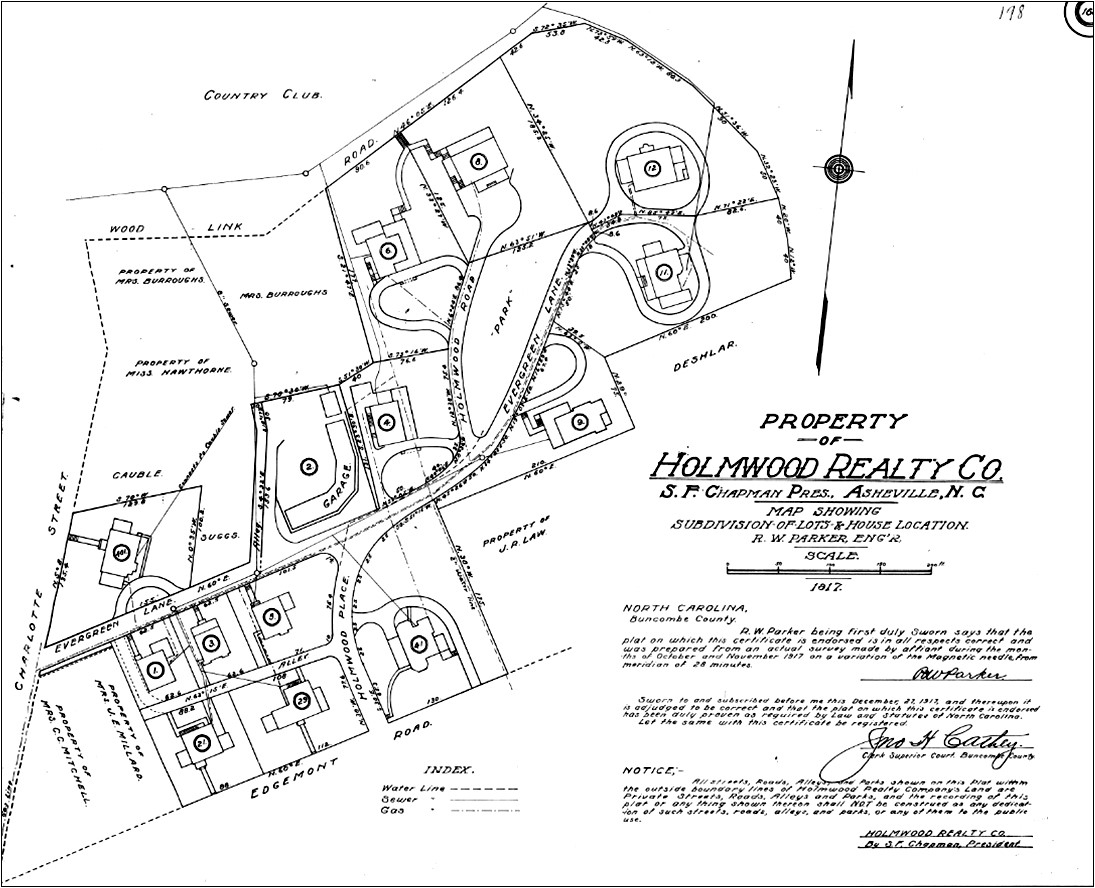

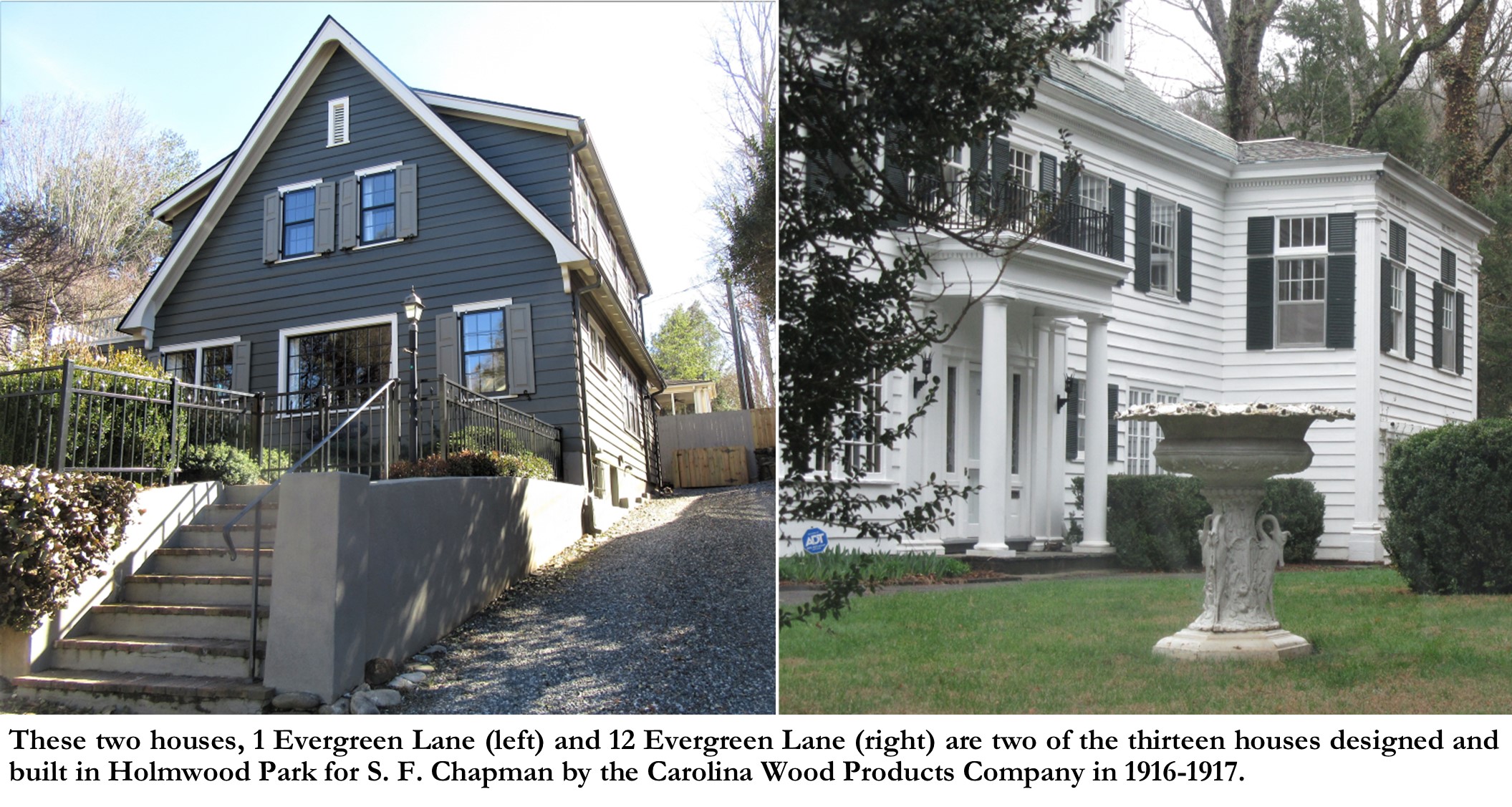

Another large project that Carolina Wood Products Company contracted to design and build in 1916, was a residential development for S. F. Chapman. The front-page headlines of the September 30, 1916 edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times, boldly announced: “DEVELOPMENT CALLING FOR $150,000 ON EDGEMONT ROAD NEAR GOLF LINKS BRINGS NEW CAPITAL TO ASHEVILLE- Syndicate of Asheville Capitalists, Including S. F. Chapman and Officials of Carolina Wood Products Company, Will Make Highest Class Development Here Since Date of E. W. Grove’s First Operation”.[36] Shepard French “Frank” Chapman, a local businessman, used his experience in organization to develop his “syndicate”, which constituted a collaboration of Chapman’s newly formed, “Holmwood Realty” and the Carolina Wood Products Company. Chapman had formed the “Holmwood Realty Company” in August of 1916 with a capital stock of “$100,000 divided into 1000 common shares” with the proviso that they could commence business when they had 250 shares. Chapman satisfied this proviso by purchasing 248 shares at the start.[37] Involving the Carolina Wood Products Company was the uniqueness of Chapman’s development. Carolina Wood Products acted as a modern-day design-build firm on Chapman’s development, being responsible for both the design and construction of Chapman’s houses. Although I have not seen a catalogue of the company’s “ready-built” houses, I suspect that they used this opportunity to display their “models” in Chapman’s new development, named Holmwood Park. This was a great project for Carolina Wood Products Company, as they could show-off their house designs in a model community and have someone else pay for it!

The heart of the Holmwood Park development was a new street named Evergreen Lane, which came off Charlotte Street, just north of Edgemont Road. A cross street, named Holmwood Road, curved across the middle and connected to Edgemont Road. The houses mostly straddled Evergreen Lane and Holmwood Road, except for two houses which fronted on Edgemont Road. Interestingly, Holmwood Park was not platted until AFTER it was finished, and therefore the plat included not just the lot subdivisions but also the footprint of each house along with their accompanying walks and driveways.

Chapman obtained the building permits for the houses beginning in March of 1916; however, Carolina Wood Products Company were the contractors. Again, it is difficult to tell who the architect for the project was, and although E. A. Fonda was the spokesman for the company’s projects, and in fact is listed as the project architect in a report to the Manufacturers Record[38], I strongly suspect that Ronald Greene and his “architectural department” were heavily involved in the design of the development and the houses. One evidence of this is from a December 1916 newspaper report, where Ronald Greene was representing the Carolina Wood Products Company in a building line dispute on the Chapman development:

Architect Green [sic] of the Carolina Wood Products Company told the city commissioners yesterday afternoon that to establish a forty-foot building line on Grande Avenue [Edgemont Road] would cause the company about to make extensive developments there serious financial loss. Mr. Green [sic] went into details and showed the commissioners designs of some of the buildings to be erected there.[39]

Clearly, Greene was involved in the design and development of the houses. Just a note-although the commissioners agreed that evening to move the building line on Edgemont Road from 40 feet back to 30 feet, however, after subsequent protests from existing Edgemont Road residents resulting in months of wrangling and several commissioner meetings later, a compromise was met at 35 feet!

In the designs of the Chapman houses we see Greene’s versatility in designing in various style idioms. The thirteen houses designed and built in Holmwood Park by the Carolina Wood Products Company read like a “ready-cut” house catalog, designed in various styles- Georgian, Colonial, Dutch Colonial, Arts & Crafts Bungalow (both Craftsman & California Bungalow styles), and Shingle-style. In addition to the thirteen houses, a community garage, was built on Lot 2, in the middle of the development. The houses display the capabilities of the Carolina Wood Products Company’s millwork and sash works departments, with their trim work, brackets, shutters, oval windows, and various accurately detailed wood columns. The houses are of course wood frame and have wood clapboard or shingle siding. The houses were all originally built as furnished houses and were rented out. No doubt much of the furniture in the houses was also manufactured by the Carolina Wood Products Company. Although the community garage is long gone, most of the Chapman houses remain and add to the charm of the historic Grove Park neighborhood.

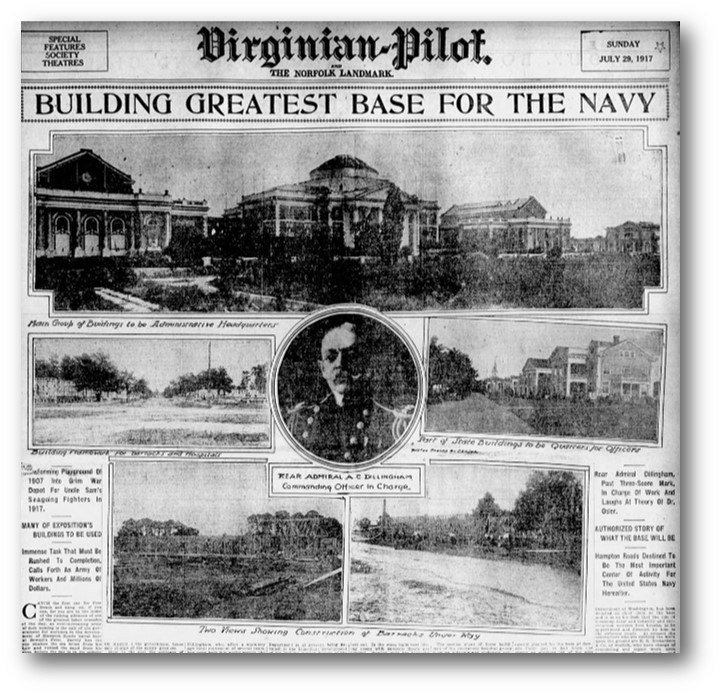

As 1917 dawned, Carolina Wood Products Company was busy completing all their projects, which they had started in 1916. However, as the war raged in Europe, it was becoming more evident that the United States would soon be drawn into the fighting. Sure enough, on April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson went before a joint session of Congress to request a declaration of war against Germany. This was to have a major impact on Ronald Greene and the Carolina Wood Products Company. In July 1917, the news broke that the Carolina Wood Products Company had landed a five-million-dollar contract to build barracks at the U. S. Naval training camp that was being built on the former site of the Jamestown Exposition site at Norfolk, Virginia. It was further reported that the furniture department of the company had contracted to manufacture standardized wooden airplane parts for the U. S. government.[40] It was later reported that Carolina Wood Products Company president, David B. Morgan, accompanied by key managers of the company (E. A. Fonda, house manager; C. J. Morgan, lumber department manager; William F. Krable, contractor) had gone to Washington and basically camped out with “every man ready to answer any question that might arise regarding his particular department, and each man ready at any minute to submit facts and figures on any proposition offered by the naval department”.[41]

The contract for the project, reported by David Morgan, included the building of: “seventy-two barracks 91 x 27; eight barracks 52 x24; twenty-four barracks 33 x 200; twenty-four barracks 35 x 22; eight barracks 27 x 32”, all of which were to be completed by August 15! The Carolina Wood Products Company got to work immediately recruiting the needed workers, estimated to be at one thousand, by opening an office onsite to recruit local workers. Of course, the company also recruited and sent hundreds of men from Asheville and Western North Carolina to assist.

Although it’s unclear what Ronald Greene’s contribution to the project was, we know that by August 1917, he was living and working onsite in Norfolk. “Ronald Green spent the weekend in the city from Norfolk, Va., where he has been for several weeks”[42], reported the August 12, 1917, edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times. Greene stayed in Norfolk, with occasional visits back to Asheville, until January of 1918, when he moved back to Asheville. “Mrs. Green and Mr. Ronald Green came Sunday from Norfolk, Va., Mrs. Green will spend several days here before returning to her home in Michigan. Mr. Green will remain indefinitely here.”[43], reported the January 15, 1918, edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times.

Ronald Greene had not been back in Asheville but four months when he suddenly found out that he was losing his job. In May of 1918, the Carolina Wood Products Company announced that the company had reorganized. The company, which had been originally chartered as the Carolina Wood Products Company of Maine, reorganized as the Carolina Wood Products Company of Delaware. Part of the reorganization was the decision of the new company, still named Carolina Wood Products Company, to center exclusively on the “manufacture of furniture and core stock”.[44] To that end, they sold their tanning extract company in Andrews, and shut down their house department and contracting business. The following month, June 1918, Ronald Greene returned to his home in Coldwater, Michigan, “for a stay”.[45]

Although the Carolina Wood Products Company’s brief, yet productive, two-and-a-half year stint at building was over by the end of 1918, and would prove to be but a flash in the pan in Asheville’s architectural history, Ronald Greene would eventually return to Asheville to make his indelible mark on the architecture of Asheville, Buncombe County, and Western North Carolina. But that’s a story for another time!

Photo Credits: All captions by the author.

Rendering of the Jackson Building- Image A175-8 -Architectural rendering of the Jackson Building on Pack Square, built in 1924 for L.B. Jackson, by architect Ronald Greene. -Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

Pratt Institute-School of Fine Arts Class, 1913- Insert portrait of Greene inserted by author. –Image from: Pratt Institute. 1913 Annual –https://jstor.org/stable/community.34330521.

Graham County Lumber Mill, Andrews, NC- “Band Mill, of Graham Co. Lbr. Co., Andrews, N.C.”, postcard dated 1916, published by Davis Pharmacy. Western Carolina University, Cullowee, NC -Regional Photographs Collection. https://southernappalachiandigitalcollections.org/object/62405

Carolina Wood Products Company Mill, Asheville, NC- University of North Carolina Asheville, E. W. Ball Photographic Collection, Ball1775– accessed from: https://southernappalachiandigitalcollections.org/object/3820

Photo of Swollen French Broad River, 1916 Flood- “From: The Floods of July 1916”, copyright 1917, Southern Railway Company. Call Number F215.F55 1917.– NOAA Photo Library. Archival Photography by Steve Nicklas. Accessed from: https://photolib.noaa.gov/Collections/National-Weather-Service/Meteorological-Monsters/Floods/emodule/645/eitem/3059

Postcard showing old Dreamland Theater at Pritchard Park- ImageAC108- Colored photo-offset, divided back, of old Post Office (1892) which stood at present site of Pritchard Park. To left is Dreamland Theater at #81 Patton Ave. – Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

Aladdin Homes 1915 Cover- “Aladdin Houses 1915”, (Bay City, MI: North American Construction Company, 1915) cover page.

Kenilworth Inn- photo by Dale W. Slusser

Hester Bungalow at 8 Bowling Park Drive- Image F817-5- Recently completed house at 8 Bowling Park Rd in Kenilworth, 1917. Sidewalk and border landscaping not yet finished. -Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

Carolina Apartments– Image N752-5, Print was acquired from City of Asheville and is listed as #111 in Historic Architectural Resources of Downtown Asheville N.C. (Ref. N.C. 975.688 H67). – Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

Powell Bungalow collage- Sanborn Map 1925 over Plat from Buncombe County Register of Deeds, newspaper clippings from newspapers.com-collage made by Dale Slusser

Holmwood Park Plat– 12/29/1917 HOLMWOOD REALTY COMPANY -PLAT CHARLOTTE STREET Db. 198 pg. 166. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Photos of 1 Evergreen Lane & 12 Evergreen Lane- photo by Dale W. Slusser

Virginia Pilot Newspaper Article- “BUILDING GREATEST BASE FOR THE NAVY”, The Virginian-Pilot, Norfolk, Virginia ·July 29, 1917, page 1. -newsppaers.com

[1] North Carolina Business History-website: https://www.historync.org/NCCityPopulations1800s.htm

[2] Fashionable Asheville, Part Two, by David Coleman Bailey (Asheville, NC : David Coleman Bailey, 2004) page 121.

[3] “Report Of The Coldwater High School Alumni Association, 1913”, -http://files.usgwarchives.net/mi/branch/schools/coldwate12gms.txt

[4] “Early Years of the Pratt Institute”, by Sarah Quick, March 25, 2022, Brooklyn Public Library Blog,- https://www.bklynlibrary.org/blog/2022/03/25/early-years-pratt

[5] “PRATT SENDS FORTH CLASS NUMBERING 453”, Times Union, Brooklyn, NY, June 17, 1913, page 3. -newspapers.com

[6] “MR. RONALD GREENE”, Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, MC, October 13, 1961, page 11. -newspapers.com

[7] “Cleveland Sixth City Directory, For the Year Ending August, 1915”, (Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Directory Company, 1914) page 602. – https://cplorg.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16014coll29/id/23661/

[8] The Beaux Arts Atelier system has and is making a twenty-first century resurgence here is the United States, mainly through the auspices of the The Institute of Classical Architecture & Art (ICAA), which is a nonprofit membership organization committed to promoting and preserving the practice, understanding, and appreciation of classical design. See website: https://www.classicist.org

[9] “L’École Des Beaux-Arts”, by Stephen Bau, Nov 17, 2022. – https://bauhouse.medium.com/le%CC%81cole-des-beaux-arts-83e0fc0840c4 See also: Warren, Lloyd. “The Atelier System.” The American Magazine of Art 7, no. 3 (1916): 112–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20559293

[10] “Beaux-Arts Institute of Design”- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaux-Arts_Institute_of_Design See also: “The Society of Beaux-Arts Architects.” Art and Progress 6, no. 5 (1915): 170–170. – http://www.jstor.org/stable/20561410

[11] “Beaux Arts Institute of Design-Landmarks Commission of NYC” report: http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/1667.pdf

[12] “IMMENSE NEW LUMBER COMPANY FOR ANDREWS- Graham County Lumber Company To Erect Wood Working Plant at Andrews”, Asheville Times, February 15, 1915, page 10. -newspapers.com

[13] “COL. FRANK BUELL BUYS THE ANDREWS LUMBER COMPANY” Asheville Citizen-Times, February 14, 1915, page 20. -newspapers.com

[14] “EXTRACT COMPANY REPORTED AS BEING SOLD”, Asheville Times, November 11, 1914, page 5. -newspapers.com

[15] “ASHEVILLE SELECTED FOR INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT OF IMMENSE PROPORTIONS”, Asheville Citizen-Times, October 22, 1915, page 1. -newspapers.com

[16] Ibid.

[17] “ASHEVILLE SELECTED FOR INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT OF IMMENSE PROPORTIONS” continued, Asheville Citizen-Times, October 22, 1915, page 2. -newspapers.com

[18] Ibid.

[19] “STARTING BUSINESS UNDER ITS NEW NAME”, Asheville Citizen-Times, January 24 1916, page 6. -newspapers.com

[20] “The Great Flood of 1916”- https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/bcb2e5373c21491c9e68e96a8156d92b

[21] “PROPERTY LOSSES ARE FOUND TO BE HUGE”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 17, 1916, page 4. -newspapers.com

[22] “ASHEVILLE INDUSTRIES AND WHAT THEY ARE DOING, NO. 4- THE CAROLINA WOOD PRODUCTS COMPANY”, Asheville Citizen-Times, September 3, 1916, page 8. -newspapers.com

[23] Ibid.

[24] Asheville Citizen-Times, December 10, 1915, page 2. -newspapers.com

[25] Ibid.

[26] “MANAGER BUELL IS ENGAGING WORKERS-President of Graham County Lumber Company Seeking Experienced Men For Local Plant”, Asheville Citizen-Times, January 4, 1916, page 4. -newspapers.com

[27] “CAROLINA WOOD PRODUCTS COMPNY SIGNS CONTRACT FOR THE ERECTION OF KENILWORTH INN AND WILL START AT ONCE”, Asheville Citizen-Times, September 22, 1916, page 1. -newspapers.com

[28] Ibid.

[29] “ARCHITECT BUSY ON PLANS”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 1, 1922, page 10. -newspapers.com

[30] “DEVELOPMENTS OF OVER A MILLION DOLLARS IN ASHEVILLE”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 19, 1916, page 5. -newspapers.com

[31] “CAR LINE COMPLETED TO KENILWORTH PARK”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 4, 1916, page 7. -newspapers.com

[32] See photo: Image F817-5- Recently completed house at 8 Bowling Park Rd in Kenilworth, 1917. Sidewalk and border landscaping not yet finished. Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

[33] “DEVELOPMENTS OF OVER A MILLION DOLLARS IN ASHEVILLE”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 19, 1916, page 5. -newspapers.com

[34] Manufacturers Record, Volume 70 Issue 22 -November 30, 1916, page 65. -https://archive.org

[35] “DEVELOPMENTS OF OVER A MILLION DOLLARS IN ASHEVILLE”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 19, 1916, page 5. -newspapers.com

[36] Asheville Citizen-Times, September 30, 1916, page 1. -newspapers.com

[37] 08/25/1916 Holmwood Realty Company, INC, Db. C004/250.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[38] Manufacturers Record, Volume 70 Issue 14 -October 5, 1916, page 87. -https://archive.org

[39] “WILL DECIDE STREET BUILDING LINE TODAY”, Asheville Citizen-Times, December 27, 1916, page 12. -newspapers.com

[40] “FIVE MILLION DOLLAR CONTRACT LANDED BY LOCAL FIRM, REPORTED”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 4, 1917, page 3. -newspapers.com

[41] “CONTRACT AWARDED LOCAL FIRM IS FORERUNNER OF MANY OTHERS”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 5, 1917, page 10. -newspapers.com

[42] Asheville Citizen-Times, August 12, 1917, page 10. -newspapers.com

[43] Asheville Citizen-Times, January 15, 1918, page 6. -newspapers.com

[44] “WOOD PRODUCTS COMPANY REORGANIZED WITH NEW CHARTER”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 26, 1918, page 2. -newspapers.com

[45] Asheville Citizen-Times, June 9, 1918, page 7. -newspapers.com