by Dale Wayne Slusser

We preservationists have flown banners in front of historic properties which tout: “THIS PLACE MATTERS!”. But what do we mean by the word PLACE! The house that Samuel D. Holt built in 1906, at 162 W. Chestnut Street, for me is an example to explain what we mean by PLACE. The sociological concept of a “A Sense of Place”, is defined (by those smarter than me) as “emotive bonds and attachments people develop or experience in particular locations and environments”.[1] “In human geography, the term place refers to areas that people create in their minds to segment locations they know. When people think of a place they usually think of areas, buildings, or other locations that they know very well and are able to describe and locate. A sense of place is a concept to explain how people define and categorize locations in their minds.”[2] The “Sense of Place” which the Holt house evokes in me is threefold, as I associate it with its interesting “Pre-history” (what happened on that site, and who lived on it before the house was built), its individual history, and its ongoing history and preservation and those connections to its past! To simplify, and bring us out of the miry world of metaphysics-the Holt house reminds me first of its association with the early settlement of Buncombe County and the famous or perhaps infamous story of early land speculator John Gray Blount; secondly of the African-American families that first owned and occupied the property prior to the building of the house; thirdly, I’m reminded of its “story” and the role it played in the post-Civil War growth of the “suburbs” in Asheville history; and lastly, it reminds me of its own ongoing history and its recent restoration, and our responsibility to preserve the history of this important and historical PLACE.

The land on which the house at 162 W. Chestnut sits, was mostly uninhabited until after the Civil War, and its origins are an integral part of the history of the early settlement of Buncombe County, involving two key figures, surveyor John Strother and speculator John Gray Blount. A watercolor map of a compilation of Land Grants in and around Asheville, which I discovered in the Clara Patton Murphy Collection at the Old Buncombe County Genealogy Society, will be our first point of reference. The watercolor map is undated and untitled, but I suspect it came from the papers of James Patton, an early settler of Asheville. Patton, along with his son-in-law Andrew Erwin moved to Buncombe County in 1807 from Wilkes County, NC. The firm of “Patton & Erwin” bought up many tracts of land in and around Asheville, and because the majority of the tracts on the map reference Patton & Erwin, I assume the map was composed for James Patton (who bought out Erwin in a single day in 1814) or his heirs. Nonetheless, the map provides us with a look at the early settlement and development of Asheville.

In the upper left corner of the map, which represents the northwest section of Asheville which now forms the Montford neighborhood, is a Grant/Warrant with the name “John Strother”, between the William Welsh tract on the west and the Zebulon & Bedent Baird tract to the east. From the John Strother tract came the land which is now the site of the house at 162 W. Chestnut Street. However, the original owner of the tract was John Gray Blount. The story of the Holt house, begins with these two men, John Strother and John Gray Blount, and their complicated partnership, and the story of the early land speculations in Buncombe County.

Beginning in the late 1770’s and early 1780’s, even before the land had been ceded by the Cherokee, North Carolina began issuing and selling land grants in its western lands, which then included parts of what is now Tennessee and Western North Carolina (including Buncombe County). However, in 1794-1795, the North Carolina legislature made a bizarre and irrational decision, whereby “Land speculators were allowed to apply and receive enormous blocks of lands in Western North Carolina with scant regard for pre-existing land holders. These tracts blanketed multiple small existing tracts and generated much anxiety and likely legal action.”[3] In the early 1790s John Gray Blount began speculating in North Carolina lands in earnest. He acquired land for himself and associates in a multitude of entries in various eastern counties and in Buncombe totaling more than three million acres. These entries were surveyed individually by the county surveyors and their deputies. Some of the larger entries were for huge tracts that embraced earlier grants to landowners or their predecessors.[4] One of these large speculation grants was “Grant No. 253”, for 320, 640 acres taken out by John Gray Blount in 1796.[5] This one grant included all the land west of the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east bank of the French Broad, bordered on the south by the Swannanoa River and the north by Warm Springs, and the Toe River area. Fortunately, a few of the earlier tracts that were already being entered were excluded from the John Gray Blount Grant, including a grant to John Burton for the town of “Morristown”, which changed to Asheville when it was founded in 1792.

The extent to which these earlier grants were excluded from “Grant No. 253”, is beyond the purview of our discussion. Suffice it to say that the land upon which the house at 162 W. Chestnut Street sits, WAS included in the Grant and subsequently came from a 52-acre remnant of that Blount Grant 253. Let me explain further, but first let me introduce you to the other key player and facilitator in most of the John Gray Blount speculative grants, John Strother. “Blount found that to dispose of his speculation lands to advantage he needed surveyors who were capable of joining these multitudes of surveys into general plans delineating the whole and the watercourses that drained them, or of laying out the great tracts in a manner that showed in correct detail the property lines of those who owned land within the tract under earlier patents of title. For this purpose he employed two men: Jonathan Price, of Pasquotank County, who had an established claim to the skills of a topographic surveyor, and John Strother, who probably was introduced to John Gray Blount by [Blount’s brother] Governor William Blount.”[6] Although Price and Strother, with the aid of John Gray Blount, would eventually corporate together to produce the first comprehensive topographical map of the State of North Carolina (published in 1808), it was Strother who was Blount’s primary agent in pursuing and registering Blount’s vast speculative grants.

John Strother, land agent and topographical surveyor, was born in Culpeper County, Va., the son of George and Mary Kennerly Strother. Sometime after 1785 young Strother left Culpeper County, Va., for Wilkes County, Ga., presumably drawn there as a surveyor by Georgia’s intended opening of the Indian lands lying on its northern and northwestern frontiers. During his work for Georgia, Strother met William Blount, the governor of the then Tennessee Territory. Blount was a native of Bertie County, North Carolina and was the brother of John Gray Blount. The year in which Strother met John Gray Blount, or how early he was employed by Blount, is unknown, but from the records it’s clear that by 1795, John Strother was working for John Gray. Although the friendship of Strother and Blount would last for Strother’s lifetime, the fate of John Gray Blount’s vast speculative holdings was very short lived, especially those of Grant No. 253 and his other Buncombe County grants. In fact, Blount’s trouble began in 1796, the very year that he received the grant, when he was unable to pay the vast amount of Buncombe County taxes owed on his vast holdings. Finally, on the 29th day September 1798, James Hughey, high sheriff of Buncombe County, in order to satisfy the public and county tax due for the year 1796 (on the Blount lands) famously sold over one million acres of Blount’s land at a County Courthouse sale. Interestingly, Strother purchased 546,880 of the more than one million acres of the speculation lands at a tax sale. He took the deed from the sheriff in his own name and immediately began selling the land in small tracts to local buyers, giving personal deeds of title to the purchasers. He was, of course, acting for Blount in these transactions, as is evidenced by the fact that one of the provisions of his will was to return the unsold balance to Blount.[7] Yes, in an interestingly twist, John Strother died in 1815, and in his will (dated 1806) he bequeathed to John Gray Blount (who obviously outlived Strother) all of the residual Blount lands which he had not previously sold off.[8] And in our case, this included a 52-acre tract remaining from Blount’s Grant 253. This same tract, shown as a John Strother tract shows on the Patton surveys map mentioned previously. In April of 1829, John Gray Blount sold this tract to Jacob Summey.[9]

Jacob Summey owned and lived on lands in Henderson County, NC at Mills River, so he never occupied the Asheville tract, and in fact in 1835 (no doubt on the promptings of his wife Polly Mira Avery Poor Summey) Jacob Summey sold the 52 acre tract to his stepson, Isaac T. Poor.[10] Around that time Isaac Poor had gone into partnership with J. Dunlap to open a dry goods, general store in downtown Asheville. I’m not sure if he occupied the 52-acre tract or lived above the store in downtown Asheville. But unfortunately, Isaac T. Poor died suddenly in 1842 at the age of 34. In his will he devised all his property (including the 52-acre Strother tract) to his mother, Polly M. Summey.[11] Polly Summey, held on to the 52-acre tract until 1852, at which time she sold the property to Nicholas W. Woodfin.[12]

Nicholas Washington Woodfin, lawyer, legislator, and planter, was born in 1810, in the Mills River section of that part of Buncombe County (now part of Henderson County). He was the fourth of twelve children of John, a prosperous farmer, and Mary Grady Woodfin. Nicholas not only became a distinguished member of the Asheville bar and a state senator for five terms, but he also acquired extensive acreage in the French Broad River valley, and he owned the largest number of enslaved people—122—owned by anyone in Buncombe County in 1860. That year he valued his real estate and personal property at $165,000. In 1870, however, the total value of his property was given as only $36,000.[13]

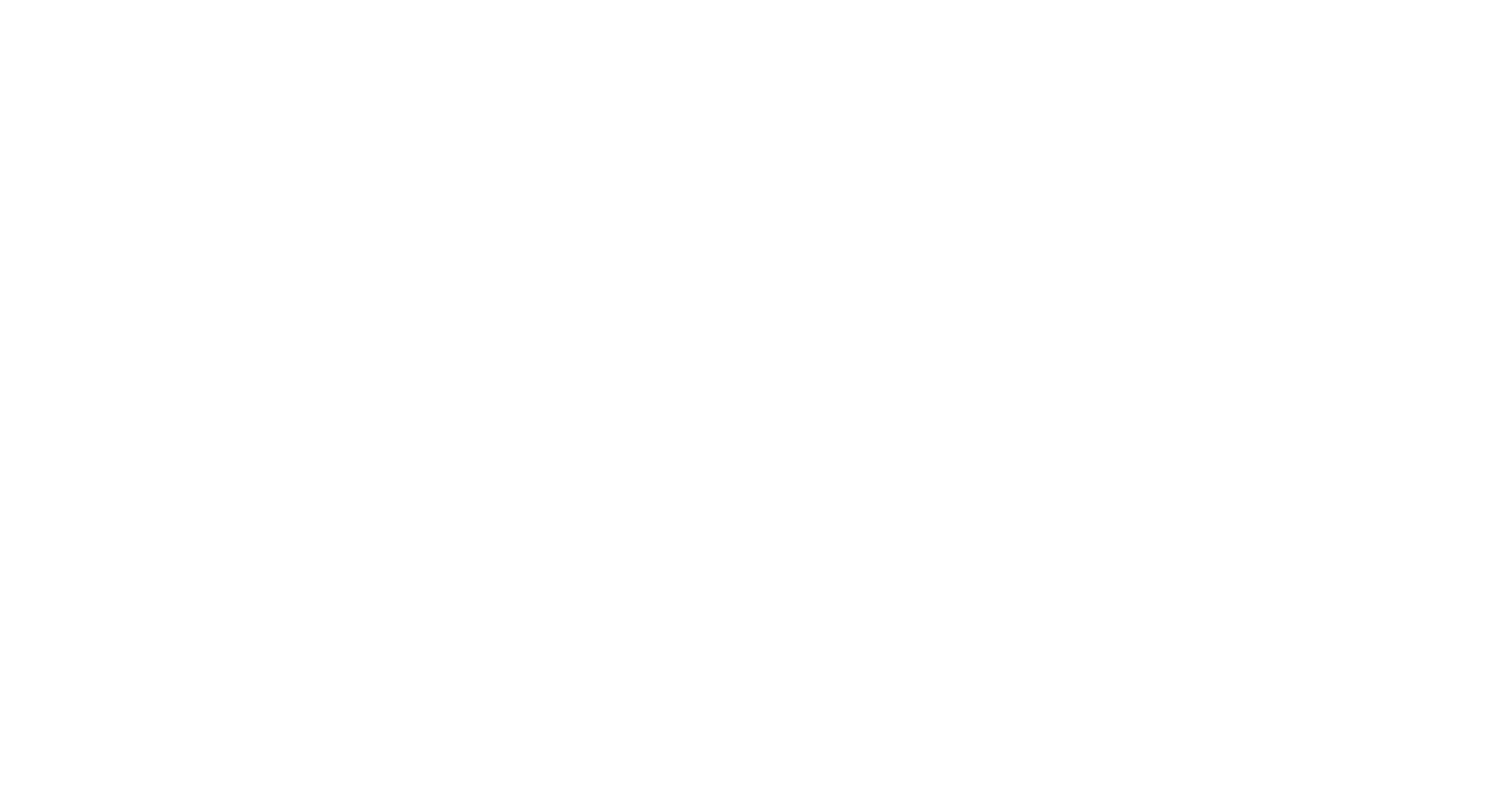

Why did a prolific and astute lawyer, who lived in downtown Asheville have so many enslaved people? Simply, because he was also an avid agriculturist (aka: gentleman farmer), noted for his “intensive farming” techniques, which maximized agricultural production on a given area of land with inputs such as labor, fertilizer and machinery. Woodfin owned an extensive farm up on Elk Mountain in the Beaverdam area, northeast of downtown Asheville. He also owned large farms along the east bank of the French Broad River, northeast of Asheville. Those farms, in the late-nineteenth century and early twentieth century, after Woodfin’s death, became known as “The Woodfin Lands”[14], which eventually turned into the town of Woodfin, NC. The 52-acre tract that Woodfin purchased from Polly Summey was near, but not connected to the “Woodfin lands”, but nonetheless served as agricultural land. In subsequent property transfers, the land was always described as part of the “Old Fields”. In fact, all of what is now the Montford neighborhood, was then known as the “old fields”, owned either by Woodfin or the Patton Estate. These “old fields” clearly show on an 1851 lithograph by Sarony & Major (117 Fulton St, NY), titled, “View of Asheville N.C. and the Mountains from the Summer House”, which was published by Asheville newspaper publisher, James M. Edney.[15]

Just prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, Asheville had begun expanding out towards the “Old Fields”. In 1858, through the auspices of Nicholas Woodfin and other interested patrons, a new site and a new brick building was procured for the “Asheville Male Academy”, a decades old school for boys. The “new” home of the Academy was in the “Old Fields” just north of what is now the intersection of Haywood Street and Montford Avenue. The street out to the Academy was first appropriately named “Academy Street”, but in the 1890’s with the development of the Montford suburb, the street name was appropriately changed to Montford Avenue. The Asheville Male Academy, at the start of the public school system in Asheville in the 1880’s became the Montford Avenue School, and it the 1890’s the 1858 building was replaced by a large two-story school. The site to this day is still used as a school-first the Montford Avenue School was replaced by the W. F. Randolph Elementary School, and recently the site has been used by the public school system as a new STEM school called the Montford North Star Academy.

As mentioned earlier, by 1870, Nicholas Woodfin’s “property value” had dropped by 75%, obviously due to the economic losses of the civil war and the emancipation of enslaved people, which resulted in a loss of “free labor”, and therefore a decline in his agricultural pursuits. Apparently, the “old fields”, then described as “just beyond the Academy”, became fallow. But then in 1868, the three years after the close of the War, Nicholas Woodfin, was prompted I believe by his charitable daughter Anna Woodfin, to sell bits of the “Old Fields” to African Americans as homesites. Of course, Woodfin chose to sell the sites to loyal family servants who had served the Woodfin family (first as enslaved, then as hired servants). Of course, Woodfin chose to sell the sites to loyal family servants who had served the Woodfin family (first as enslaved, then as hired servants). Although Woodfin gave part of the land to his daughters, Anna Woodfin, Lillie Benson & Mira Holland, who after his death would inherit the remainder of the 52-acre Polly Summey tract, he gave through them, in 1868, a one-acre plot of land to the family’s longtime nurse/nanny, Tempie Avery. The daughters financed the building of a small house for their beloved African American nanny. The plot and house were at the corner of what is now the intersection of Pearson Drive and Gay Street, on the site of what is now called the “Tempie Avery Montford Community Center”.

That same year, 1868, Nicholas Woodfin also sold a 2-1/2-acre plot just across Pearson Drive (to the east) from Tempie Avery’s lot to the Woodfin family’s servant/butler, Lorenzo Love. The property was known as Lot. No. 8 on a survey/subdivision made by Thomas W. Patton.[16] The lot was in the “Old Fields” near the Asheville Male Academy, at the northwest end of North Main Street. When the Montford Subdivision was formed twenty years later, the Love property formed the southwest corner of Gay Street and Montford Avenue and extended west to Pearson Drive. The property now encompasses numerous lots from the southwest corner of Montford Avenue and West Chestnut westward along the south margin of West Chestnut to Pearson Drive.

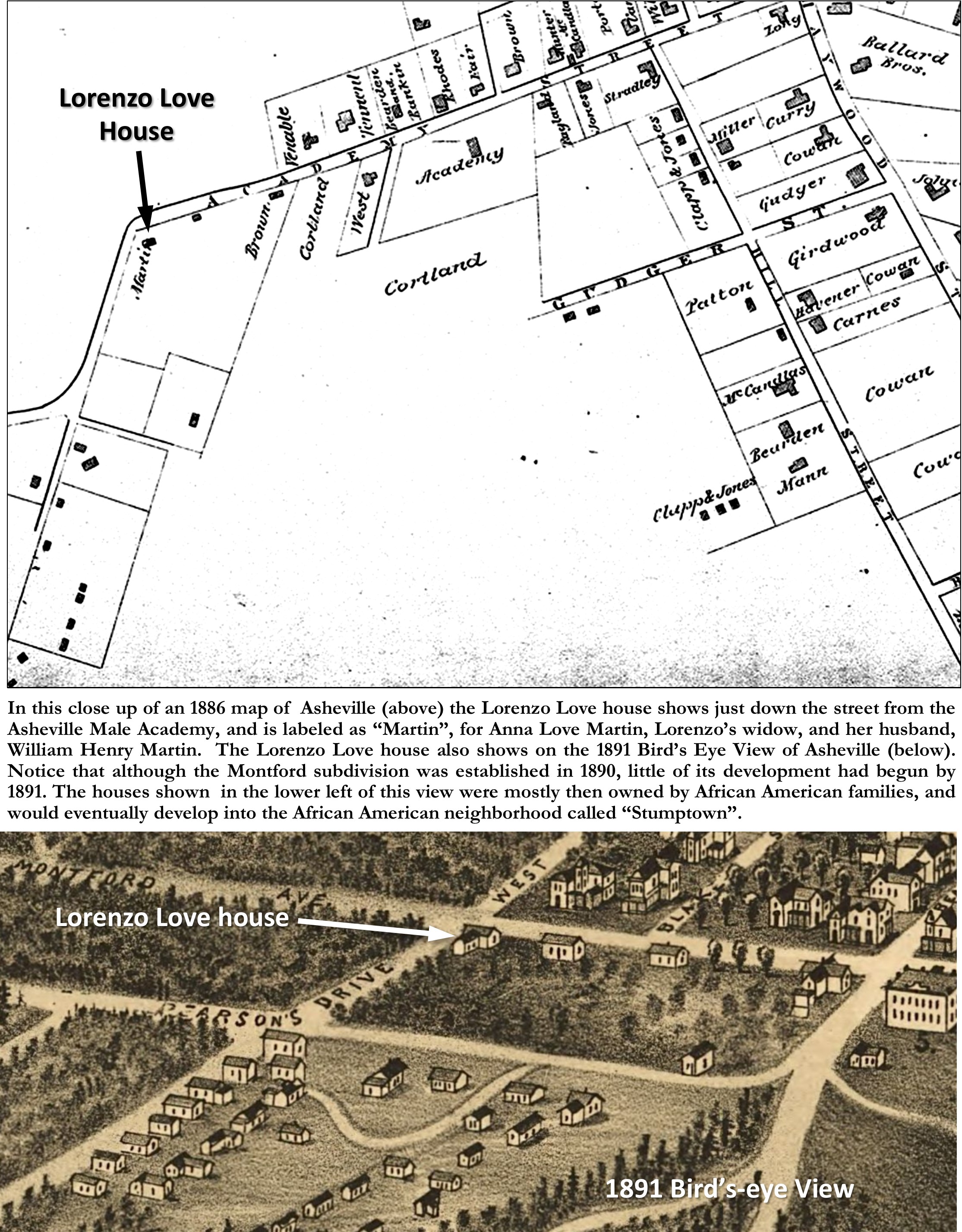

Lorenzo and his wife Anna Wilson Love built a small house on the eastern end of the lot facing North Main Street (Montford Avenue). Woodfin sold the property to Lorenzo in 1868 for $175 but held the mortgage and owner-financed the property to Love. Lorenzo Love paid off the mortgage in just a few years and was granted full title to the property by Nicholas Woodfin in 1871.[17] Unfortunately, Lorenzo Love died the following year, 1872, leaving behind a widow, Anna Wilson Love, and two children, a son John and daughter Lu. Fortunately, Nicholas Woodfin prepared a thorough Will for Lorenzo in August 1872, just prior to Love’s passing. In his Will, Lorenzo Love gave a life estate to his wife, which included the house and garden “to the extent of one-half acre on the Eastern end or part” of his 2-1/2 acre property. He further bequeathed a life estate to his mother, Lazenia (or Louzenia) Brown and her husband Daniel Brown, “three-fourths of an acres on the lower western end of said lot adjoining Temple Avery’s lot, to run in a compact form as nearly square as may be”. But the entire property was left (including a reversionary interest in the portions bequeathed to his wife and mother-upon their deaths) to his son, who he describes as, “John Quincy born before the marriage between me and my wife”, and to “Lu Emma Kate, born since said marriage”, to be held jointly by his two children. Interestingly, later in official documents, in their adult years, the children always used: “John Lorenzo Love” and “Lula E. Love”. Anna remarried four years later, in 1876, to barber William Henry Martin, to which she subsequently bore three more sons and another daughter. Anna and her children, John & Lula moved from the house on the Love property to William’s house at 102 Mountain Street (now part of the East End). Anna passed away in August of 1890. At the time, John & Lula were 21 and 19 years of age (respectively) and living at the Martin home on Mountain Street. The Mountain Street house was closer to Martin’s barbershop, which was on the north side of Pack Square. The Love property was then leased out. Daniel Brown, Lorenzo’s mother’s husband, and his wife Lazenia (Lorenzo’s mother) continued to occupy their portion of the property, and in addition, Daniel Brown built and operated a butcher shop along Academy Street, just south of the Love dwelling.

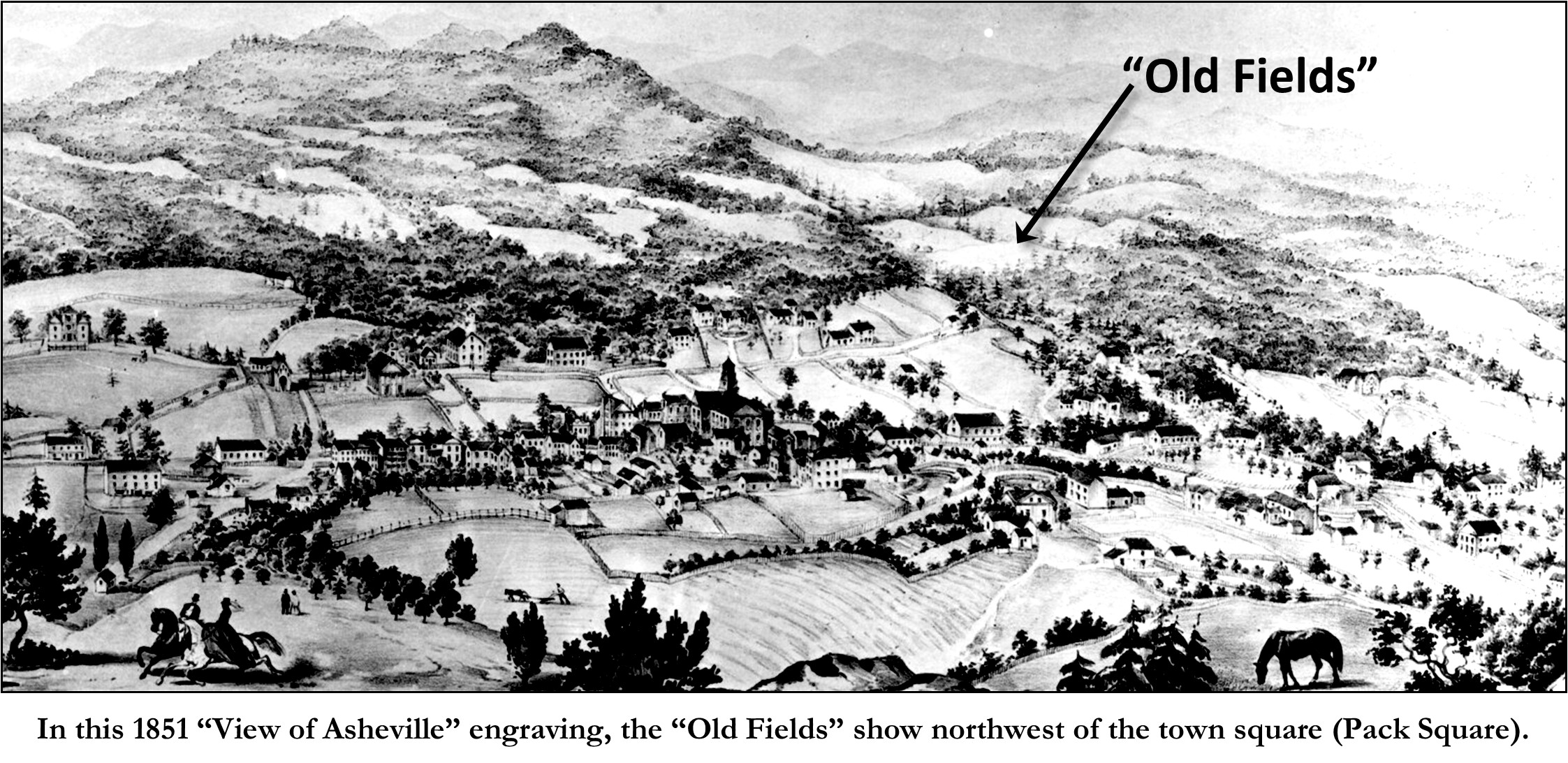

An 1886 map of Asheville shows the Love property on Academy Street just north of the “Academy”. Two structures are shown on the east side of the property, with the lower structure labeled “Brown”, which was his butcher shop, and the structure above at the corner of Gay Street (W. Chestnut) and Academy Street (Montford Avenue) which was labeled as “Martin” was obviously the Love dwelling, mistakenly then thought to have been owned by Martin, although at the time he only shared in a “life estate” with his wife, Anna Love Martin. A smaller structure shows in the lower western end of the Love property, which was no doubt a small house built for Daniel & Lazenia Brown. Even as late as the 1891 Bird’s Eye View Map of Asheville, the Love property and its buildings are some of the only few buildings shown in that area of town. Although Montford had been established the year before (1890), little development around the Love property had yet begun.

The stories of John & Lula Love are too long to fully document here, except as pertain to this property. In 1890, following the death of their mother/stepmother, Anna Wilson Love Martin, John & Lula were sent off to college (I suspect through the auspices of the work of St. Mathias Church), John to Oberlin College, in Ohio and Lula to Livingstone College in Salisbury. After graduating from Oberlin John transferred to the Catholic University, in Washington, DC. Lula subsequently attended and graduated from Howard University. However, by the mid-1890s, both John & Lula had returned to Asheville and were teaching in the public schools.

In May of 1894 John & Lula had the property surveyed and subdivided into six lots. They decided to equally split their inheritance with John taking title to Lots 2, 4, & 5 and Lula taking Lots 1, 3, & 6. Although they may have intended to sell each of their lots separately, in 1899, John & Lula, who had both recently accepted teaching positions in Washington, DC, decided to sell the property in its entirety to Alabaman Samuel Doan Holt, for $5,000. Both siblings subsequently moved to Washington, DC, where they were taken into the home of noted black educator, Anna J. Cooper. Both John and Lula became notable teachers (John later as professor). John even became an early leader in calling for “black rights”, with his 1899 publication of The Disenfranchisement of the Negro. John married Sallie C. Jordan of Kansas City, MO in 1910, and died in Kansas City in 1936. His sister, Lula Emma Love married Dr. James Francis Lawson in Washington DC in 1908. Lula E. Lawson died at the age of 80 in Chicago, IL.

It was reported at the 1899 sale of the Love property to S. D. Holt, that the “unsightly Negro quarters and butcher shop” on the property in “this fashionable neighborhood” would be removed and that Mr. Holt would build a handsome residence on the lot.[18] From this description it appears that the property had not been maintained, not surprising considering that John & Lula were young absentee landlords. Sadly, this is an early example of “gentrification” in Asheville. “Gentrification” is the process whereby the character of a poor urban area is changed by wealthier people moving in, improving housing, and attracting new businesses, typically displacing current inhabitants in the process. Even today Asheville is still experiencing “gentrification”, which is impacting its historic neighborhoods. To keep our discussion germane to the story of the Holt House at 162 W. Chestnut Street, and in counterpoint to “gentrification”, Lorenzo Love and Tempie Avery were the embryos of an African American community that grew up within “this fashionable neighborhood”, that became known as “Stumptown”. It became a thriving African American community for many decades until the 1980’s-1990’s when gentrification’s twin sister, “urban renewal”, pretty much obliviated the neighborhood, although efforts are now being made to revive this historic neighborhood. [19]

Although the 1899 article, mentioned above, reported that Mr. Holt would build a handsome residence on the lot that he purchased from the Loves, and although he would eventually build his residence on part of the lot, it appears, by his subsequent actions, that his first intention for the property was potentially different than as reported. But before we go there, let’s take a look at who was S. D. Holt and what brought him to Asheville.

Samuel Doddridge Holt was born in Danville, Virginia in November of 1844 to James G. and Lucy (Burton) Holt. At some point the family moved to Yanceyville, NC. Following after the profession of his father, at the age of 14, Samuel began what would become his “business life” as a clerk in a dry-goods store in Yanceyville. Holt served in the Civil War from 1863 until the close of the war in 1865. Following the War, he moved to Montgomery, Alabama where he became a clerk in a wholesale grocery business, of which he soon was made a partner of the firm of Warren, Burch and Company. In 1869, Holt married Catherine Venable, the daughter of Thomas and Mary Venable of Prince Edward County, Va. In 1872, Holt sold out his interest in the firm and went into the coal business at Montevalle, AL. In 1881, Samuel Holt moved to Selma, AL and partnered, with a “Mr. Starr”, opened a wholesale grocery business and cotton brokerage, under the name of Holt, Starr & Co.[20] Later, Holt was associated for many years with the wholesale grocery firm of Holt, Agee, & Co. until 1899. On April 4, 1899, S. D. Holt put an advertisement in The Selma Times, announcing “Desirable Residence For Sale”, On account of failing health, I offer for sale my residence on Tremont street.”[21] So in April of 1899, at the age of 54, Samuel D. Holt moved from Alabama to Asheville.

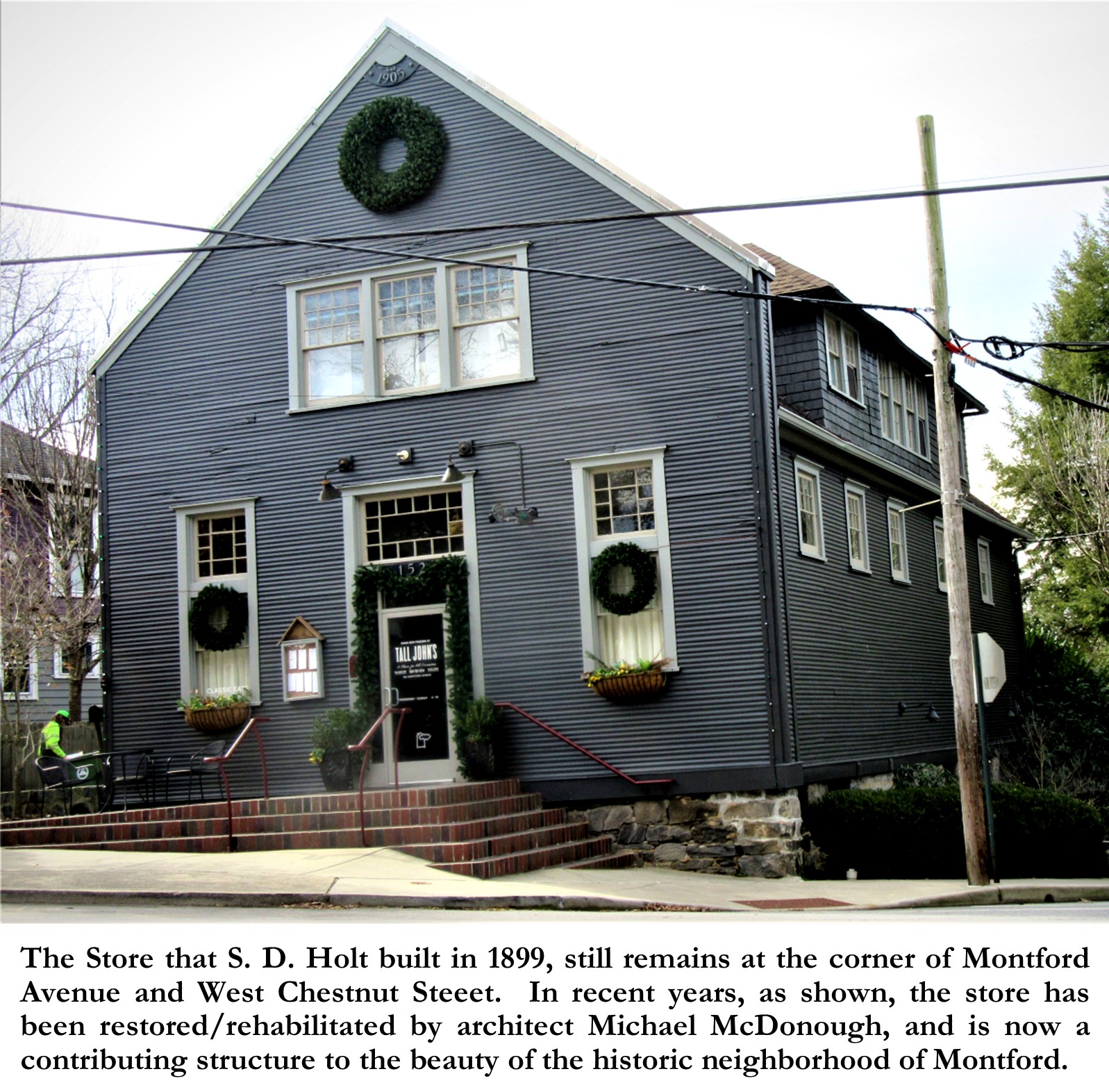

“S. D. HOLT IS BUILDING A STORE- He Will Go Into Business in Asheville, “The Land of the Sky”, announced the October 4, 1899 edition of the Selma Times.[22] “Mr. Holt has bought a lot,” it was reported, “and would build him a storehouse and would embark in the grocery business in Asheville.”[23] Holt’s grocery store was built on the east side of the Love Property at the corner of Montford Avenue and “Gay Street” (W. Chestnut), where formally sat the Lorenzo Love residence. In fact, Holt had been granted a building permit for his “frame storehouse” in April of 1899.[24] When Holt and his family first moved to Asheville they leased a house on Person Drive, nearby his property.[25] But the same week of the store announcement in October of 1899, the Holts, just arriving back to Asheville from a short visit back to Selma, moved their residence to some leased rooms at 117 Haywood Street.[26] That same month, Holt requested that the City of Asheville Board of Alderman provide “curbing in front of his lot at the corner of Montford avenue and Gay street”.[27]

S.D. Holt & Co. officially opened on January 1, 1900. “New Year-New Store,” was their buy line, offering “staple and fancy groceries, fruits, vegetables, meats, and everything needed or desired by good housekeepers.”[28] A few months later, S. D. Holt took out a year’s lease on a house at 172 Montford Avenue (now addressed as 170 Montford) and moved his family into this house, which was conveniently at the northwest corner of Montford Avenue and Gay Street (W. Chestnut Street), just across the street from the new store.[29] However, it appeared that Holt’s illness (probably a respiratory ailment) was not improving, and so surprisingly, just a few months after building and opening his new store, it was announced on May 2, 1900, that “Baird Brothers, the Patton avenue grocers, have purchased the stores of S. D. Holt & Co. on Montford avenue and took possession yesterday”.[30] Among other particulars of the sale, the announcement further reported that “Mr. Holt was forced to retire from the business on account of his continued ill heath”.[31]

Whether it was Holt’s entrepreneurial spirit or a need to continue to produce income for his family, Holt was not ready to just “retire”. Two income-producing opportunities suddenly presented themselves-one of these was obvious, the other rather unexpected! Holt’s first obvious means of income-producing was to develop the remainder of his 2-1/2 acre property. In August of 1900, S. D. Holt sold a lot at the southeast corner of his property, which faced Montford Avenue, to Eliza W. Gillis.[32] Eliza and her husband, Judge Calvin Gillis, had moved to Asheville in 1896 from Florida. But Judge Gillis passed away in March of 1900,[33] leaving Eliza a widow and three children. Eliza W. Gillis purchased the lot from Holt in August of 1900, and erected a residence, with its front facing Montford Avenue, at 134 Montford Avenue. Then in November of 1900 Holt sold a second lot from his property, along Gay Street (W. Chestnut) to J. B. & Agnes Wilson.[34] The sale was reported in the newspaper in December: the newspaper reported: “Watson & Reagan, real estate agents have sold to Mrs. Agnes Wilson a lot on Stacy [Gay] Street. Mrs. Wilson will build a cottage on the lot.”[35] The Wilson’s “cottage”, not only still stands at 178 W. Chestnut Street, but it has recently been restored and remains a contributing structure in this historic neighborhood.

The second incoming-producing opportunity, which presented itself to S. D. Holt in 1900 after selling his store-was not only highly unexpected, but rather unique! In July of 1900, between selling the store and beginning to develop his property, Holt decided to start a “rabbit-raising” business! Starting with three Belgian rabbits (who were noted for increasing 136-fold per year), and dubbing his business, “Carolina Rabbitry”,[36] Holt built a 24 x 36 rabbit house “to the rear of S. D. Holt’s & Co. store at Montford Avenue and Pearson drive”, it was reported.[37] The site of his “Carolina Rabbitry” must have been on the site of what would become, 162 W. Chestnut Street?

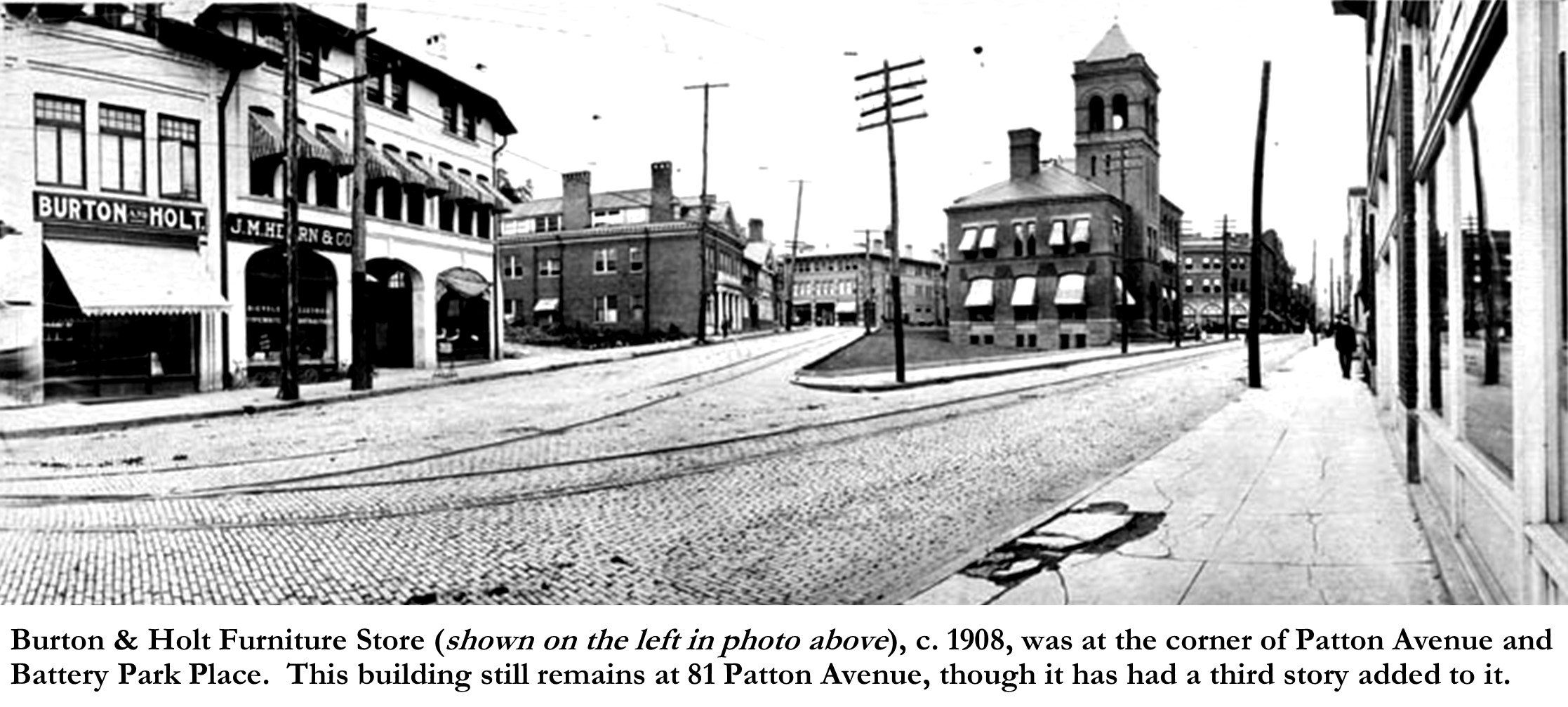

In November of 1901, Holt and his family moved back to Selma, AL, supposedly for the winter.[38] However, it appears that for the next few years, Selma was their primary residence, with periodic visits to Asheville, residing at one of the hotels or leased houses. On one of the visits back to Asheville, in 1903, Holt met Samuel P. Burton, who was then the manager/operator of Green Brothers furniture store on Patton Avenue. Burton had been the manager of the store for several years previous, working for his sister Laura A. Johnson, whose husband had started the store before his death in 1895. Upon Laura Johnson’s death in April of 1902,[39] the furniture store was bought by Gay Green. Burton stayed with Green Brothers for a year, until in 1903, as was later recalled, S. D. Holt, “espied the young furniture salesman and artisan, and lent him [Sam Burton] the money for establishment of a partnership under the name of Burton & Holt”.[40] Burton & Holt opened their furniture store at 32 S. Main Street (Biltmore Avenue) in December of 1903.[41] Also during those first few years of the twentieth-century, 1900-1905, Holt continued (through agents) to sell off lots from his 2-1/2 acre property.

In 1906, S. D. Holt decided to finally build a permanent residence in Asheville. In December of 1906, Holt took out a “Deed of Trust”, borrowing two thousand dollars ($2,000) from J. E. Rankin.[42] A deed of trust is a document used in real estate transactions. It represents an agreement between the borrower and a lender to have the property held in trust by a neutral and independent third party until the loan is paid off.[43] In this case, the “third parties”, were J. M. Siegler and his son, J. B. Siegler. J. M. Siegler was a retired grocer, and his son, James B. Siegler was, interestingly, an employee (albeit manager) of Burton & Holt Furniture Store. Besides the fact that the new Holt residence did not show up in the Asheville City directories until 1907, we know from this deed of trust, that the house was begun in late 1906, as the deed of trust, dated December 8, 1906, described the property included in the deed as “the land in which said S. D. Holt is now building a dwelling.”[44] We can assume that the Carolina Rabbitry, which was on the site was now defunct and that the “Rabbit House” had been demolished!

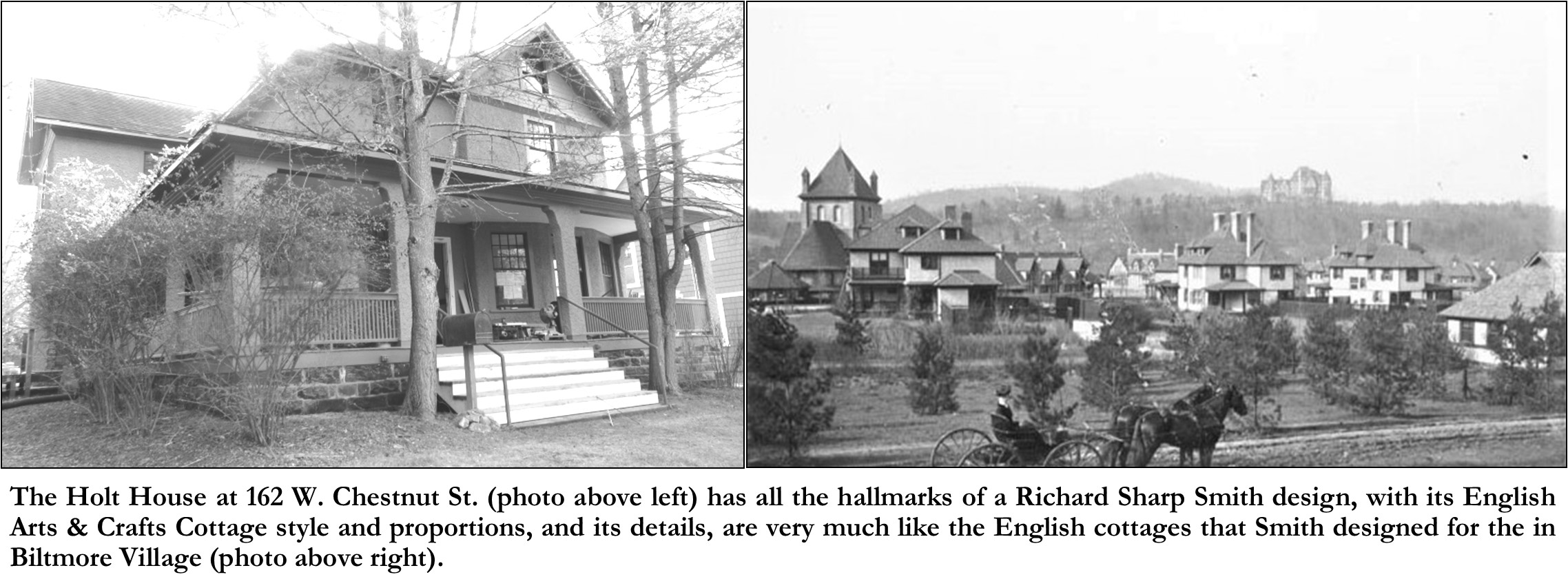

The new house that S. D. Holt chose to build was a two-story English Arts & Crafts style “cottage” fully clad with pebbledash on its exterior. The front of the house with its wrap-around porch was built to face north, parallel to W. Chestnut Street. The house’s front door opened into a large entrance hall, flanked on its right (west side) by two parlors, each with a corner fireplace, and were separated from each other by a set of large wood pocket doors. The rear of the entrance hall, opened to a back hall in which to the west and center of it accessed an odd box-shaped winding stair which went from the basement to the third-floor attic. Although the stair was clearly built as a back (servants’) stair, for some reason it seemed to be the ONLY stair in the house. Also off of the back hall, to the east, and opposite the stairs, was a dining room with an interior corner fireplace. The dining room featured. As its east wall, an angled bay with a high center window (meant to be above a buffet) flanked on each angled side by large double-hung windows. The house’s kitchen appears to have been in a small room to the rear behind the double parlors. The second floor of the new house appears to have been designed to have three large bedrooms (each with a corner fireplace), an unheated box room (storage room the size of a small bedroom), a bathroom, and numerous closets, all accessed from a center hallway.

Although I have not been able to confirm it, I strongly suspect that the Holt house was designed by architect Richard Sharp Smith. It has all the hallmarks of a Richard Sharp Smith design, and its English cottage style and proportions, and its details are very much like the English cottages that Smith had designed for Biltmore Village, and which were then being built both in Biltmore Village and around the city of Asheville. Some of the noted hallmarks of a Smith-designed house that show on the Holt house are: first of all, its pebble-dashed exterior finish (or as Smith called it, “rough cast”); it’s flared porch posts and porch railings with their simple square balusters closely placed together; also, Smith was very fond of using over-scaled double-hung windows, especially with unusual twelve over one paned sashes; and another Smith hallmark is the oversized half-class front door.

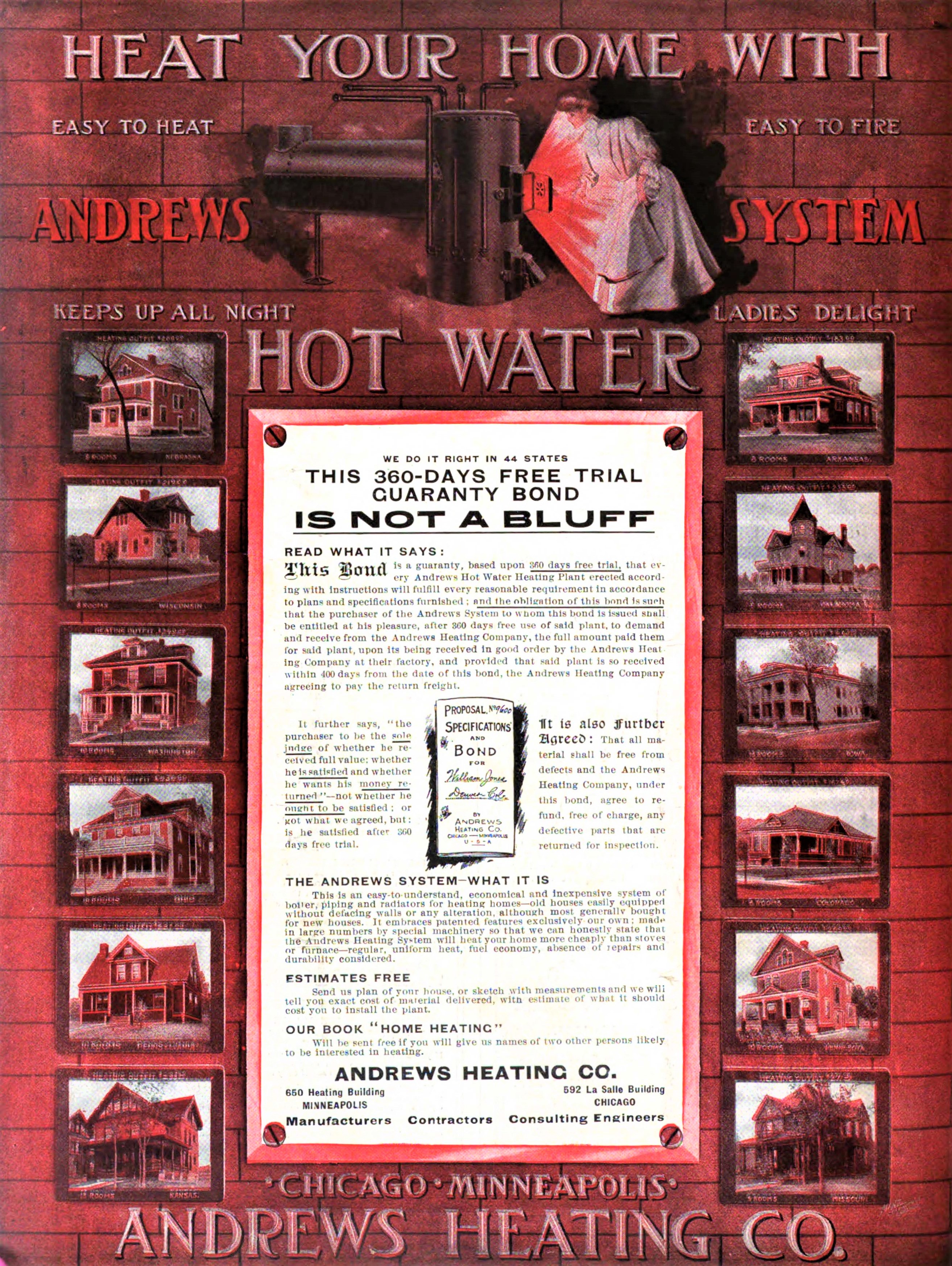

One interesting tidbit that we do know, is that the Holt house was originally built with a modern (1906) “Andrews Hot Water Heating System.” The March 1907 edition, of the trade journal, The Improvement Bulletin, in an Andrews Heating Systems advertisement, listed that one of their residential contracts for an Andrews Hot Water Heating System was “S. D. Holt, Asheville”.[45]

Samuel D. Holt only lived in his new house for seven years before suddenly passing away on July 10, 1914, just after returning to his residence from a long day of working at Burton & Holt Furniture.[46] Holt had given his wife, Catherine Venerable Holt, a life estate to the house, but upon her death the house was to (and did) go to his daughter, Miss Ellerbe Holt.[47] Just three years later, Miss Ellerbe Holt, married Wilbur Fowler, and moved to New York.[48] After Ellerbe married, being the last child to leave the nest, that left Catherine Holt alone at the house at 162 W. Chestnut Street. Catherine soon decided to move back to Selma, AL, to live with one of her other married daughters, Lucy Venerable Holt Monk. In fact, in 1921, Catherine (Kate) Holt relinquished her life estate, and moved to Selma, and Ellerbe Holt Fowler, took possession of the house, and in turn, Ellerbe immediately sold the house to Harry S. Webster.[49]

Harry Webster owned the house for barely six months, before selling the house in January of 1922 to its next longtime owner, Mrs. Elsie Boling Webb.[50] Elsie Webb, had married Porter Alexander Webb in May of 1919, but unfortunately in less than a year, in April of 1920, her husband suddenly passed away leaving her as a 25 year-old widow.[51] By 1930, Elsie’s widowed mother Eleura Boling, and Elsie’s sister Mary Boling were living in the house with Elsie. But then in 1940, at the age of 46, Elsie Boling Webb married, 54-year-old, civil engineer, Thomas A. Cox, Jr. Major T. A. Cox, as he was affectionately known, immediately moved into the house with Elsie, and lived there until his death in 1964.[52] Elsie Cox survived Major Cox by another 23 years, until dying in the house in 1987 at the age of 93, after having owned and lived in the house at 162 W. Chestnut Street for 65 years! [53]

In 1988, the Estate of Elsie Boling Webb Cox sold the house and lot to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormon Church). The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints owned and occupied the building until 2021, at which time they sold it to the current owners, Blan Holman and his wife Susannah Knox.[54]

The current owners are about to complete a major restoration/renovation of the house. They are restoring and repairing much of the original material and details such as the windows, doors, mantals, trim, interior plaster walls, and the exterior pebbledash (rough cast) finish. The odd boxed stairs in the back hall have been removed (to the second floor), and the space reclaimed for a first-floor powder room. A new stair, to the second floor, has been built in the front entrance hall, not only in keeping with the period of the house, but perhaps as originally intended by its architect! The two parlors and dining room have been restored, and a new large modern kitchen has been installed in an open space which was formerly a warrant of small kitchen/utility rooms. On the second floor, the main four bedrooms have been restored, a new family bathroom has been added off of the central hallway, and former spaces at the rear of the second floor of the house have been reconfigured into a modern primary bath and space for the washer and dryer. Also, all the house’s electrical, plumbing, and mechanical systems have been updated.

The Holt House at 162 W. Chestnut Street, reminds us of our ongoing purpose and responsibly to preserve our historic residences and neighborhoods for future generations. But even more importantly, these houses, neighborhoods, and buildings should be preserved, not just to preserve their physical properties, but to preserve the history, stories and memories associated with them, which for us, preserves their ‘SENSE OF PLACE”.

Photo & Image Credits: (Note: All cropping and captions by author)

Holt House at 162 W. Chestnut Street- Photo by Dale Slusser, January 2023.

Patton & Erwin Survey Map- Clara Patton Murphy Collection, Old Buncombe County Genealogical Society, 128 Bingham Rd., Ste. 950, Asheville, NC 28806. Digitized photo of survey map taken by Dale W. Slusser.

John Gray Blount portrait– from “Blount Researcher”, Find a Grave ID 46608462. https://images.findagrave.com/photos/2007/175/20063431_118281932754.jpg

Nicholas W. Woodfin- from portrait published in: Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present, by Samuel A. (Samuel A’Court) Ashe. (Greensboro, N.C. : C. L. Van Noppen, 1905). Accessed from archive.org

“Old Fields” on 1851 View of Asheville- View of Asheville, N.C. and the mountains from James W. Patton’s summer house, looking east. Photo of a lithograph by Sarony & Major. Published by James M. Edney, 1851. https://southernappalachiandigitalcollections.org/browse/search/asheville-north-carolina-and-the-mountains-from-the-summer-house/search/ac-collection:picturing-asheville-and-western-north-carolina

1886 Map Closeup- #MAP200, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library Asheville, NC.

1891 Bird’s Eye View of Asheville Closeup- Ruger & Stoner, and Burleigh Litho. bird’s-eye view of the city of Asheville, North Carolina. [Madison, Wis, 1891] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/75694894/.

John L. Love- photo originally published in: The Crisis, Vol. 37, No. 6, (New York, NY: The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc., June 1930), pg. 204. – accessed from googlebooks.com.

Carolina Rabbitry Advertisement- Asheville Citizen-Times, April 9, 1901, pg. 3. -newspapers.com

Burton & Holt Store c. 1908- Image ID- B503-S, View of Battery Park Pl* and Patton Ave, ca 1908, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library Asheville, NC.

Original Stair at 162 W. Chestnut St.-taken by James Blanding Holman, IV- c. 2022.

B & W photo of 162 W. Chestnut Street- Photo by Dale Slusser, January 2023.

Photo of Cottages in Biltmore Village- Image ID: A268-5, One print made from original Caldwell (#76) glass plate negative (GD001) stored in the vault and labeled (adhesive lower left front) “Biltmore village” and dated 1903. -Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library Asheville, NC.

Andrews Hot Water Heating System Advertisement- Shoppell’s Homes, Decorations, Gardens, Volume 10, Co-Operative Architects, October 1907, Rear Cover. https://books.google.com

Elsie Boling Webb Cox– originally shared by “naves1” on 17 Oct 2016.- https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/collection/1030/tree/14595661/person/212367341/media/ddf1b79a-754b-4cc8-8911-d88f0c90db16?_phsrc=PnA41&_phstart=successSource

New Kitchen Being Installed at 162 W. Chestnut St.- Photo by Dale Slusser, January 2023.

[1] K.E. Foote, M. Azaryahu, Sense of Place, Editor(s): Rob Kitchin, Nigel Thrift, International Encyclopedia of Human Geography,

Elsevier, 2009, Pages 96-100. ISBN 9780080449104, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044910-4.00998-6

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080449104009986 )

[2] Charlee Iddon, Sense of Place in Human Geography, History Courses / OSAT World History/Geography (CEOE) (018): Practice & Study Guide / Location & Migration as Geographic Themes. https://study.com/learn/lesson/sense-place-facts-examples-geography.html

[3] Pushing The Indians Out: Early Movers & Shakers In Western North Carolina & The Tennessee Territory. By Charles R. Haller. (Charlotte, NC: Charles R. Haller and Heirs, 2014), from Chapter 13- “Speculators In Western North Carolina”, pg. 38.

[4] “Strother, John”, by George Stevenson, 1994. Article is from the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, 6 volumes, edited by William S. Powell. Copyright ©1979-1996 by the University of North Carolina Press. accessed from NC Pedia on December 28, 2022.

https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/strother-john

[5] See the published grant along with a list of the landholders of the previous grants which this grant encompassed in, A History of Buncombe County North Carolina: In Two Volumes. By Dr. F. A. Sondley, L.L.D. (Asheville, NC: The Advocate Printing Company, 1930), pp. 839-843. See also: 11/29/1796 North Carolina State-No. 253 to John Gray Bount S1-2 320,640 ACRES FRENCH BROAD RIVER Db. 2, pg. 462.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[6] “Strother, John”, by George Stevenson, 1994. Article is from the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, 6 volumes, edited by William S. Powell. Copyright ©1979-1996 by the University of North Carolina Press. accessed from NC Pedia on December 28, 2022.

https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/strother-john

[7] Ibid.

[8] Henderson County, North Carolina, Record of Wills, 1841-1923; Index to Wills, 1841-1968; Author: North Carolina. Superior Court (Henderson County); Probate Place: Henderson, North Carolina. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/1995942:9061?tid=&pid=&queryId=73990d86e4df924026e5ace13ff6cd40&_phsrc=uNn112&_phstart=successSource

[9] 04/07/1829 (rec’d) 12/26/1829 John Gray Blount to Jacob Summey 52 ACRES FRENCH BROAD RIVER Db. 15/336. “originally part of John Gray Blount…three hundred and twenty thousand and six hundred and forty acres…sold by James Hughey, high sheriff of Buncombe County to satisfy the public & county tax due… for the year 1796…said sheriff’s deed to John Strother…the 29th day September 1798…registered…28th day November 1798…devised to the said John Gray Blount by the last Will & testament of the said John Strother deceased bearing the 22nd day of November AD 1806.”

[10] 06/23/1835 Jacob Summey to Isaac T Poor FRENCH BROAD RIVER 52 ACRES Db. 19/453.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[11] Will Records, (Buncombe County, North Carolina), 1831-1964; Index, 1831-1964; Author: North Carolina. Superior Court (Buncombe County); Probate Place: Buncombe, North Carolina-Wills, Book A-C, 1831-1897. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/2025343:9061?tid=&pid=&queryId=8797a38fc431b1fae4ad24de7813ab53&_phsrc=uNn114&_phstart=successSource

[12] 03/31/1852 (rec’d- 08/08/1872) Polly Mira Summey to Nicholas W Woodfin 52 ACRES FRENCH BROAD RIVER Db. 35/36.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[13] “Woodfin, Nicholas Washington”, by Mattie U. Russell, 1996. Article is from the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, 6 volumes, edited by William S. Powell. Copyright ©1979-1996 by the University of North Carolina Press. accessed from NC Pedia on December 29, 2022.

[14] 05/03/1882 N. W. Woodfin -PLAT ON FRENCH BROAD RIVER Db. 8/37.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[15] Copy print of a lithograph by Sarony & Major (117 Fulton St, NY), “View of Asheville N.C. and the Mountains from the Summer House”, from the east. See L721-XX for original lithograph. Published by James M. Edney, 1851 -Image # A202-8, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

[16] Although this Patton survey/plot layout is mentioned in several deeds, always without citing references, it must have never been registered as an official plat.

[17] 12/13/1871 (rec-d-01/22/1873) Nicholas & EG Woodfin to Lorenzo Love 2-1/2 acres Db. 35 / 226. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds. “whereas on the 26th day of August 1868…contracted with the said party of the second part…has been paid [$175]…” “…embracing a part of the old fields near the Male Academy being lot no. 8 lands sold by Thomas W Patton…”.

[18] “$5,000 REAL ESTATE DEAL: Prominent Alabamian Will Improve Montford Avenue Property”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 29, 1899. -newspapers.com.

[19] For more information about Stumptown see: https://montfordandstumptown.com/ and https://amiworthen.com/2022/02/20/montford-stumptown-stories/

[20] This biographical information from: “Samuel D. Holt”, The Northern Alabama Historical and Biographical Illustrated. by T. A. Deland and A. Davis Smith (Birmingham, AL: Smith & De Land, 1888), pg. 692.

[21] “Desirable Residence For Sale”, The Selma Times, Selma AL, August 4, 1899, pg. 3. newspapers.com.

[22] S. D. HOLT IS BUILDING A STORE- He Will Go Into Business in Asheville in “The Land of the Sky”, The Selma Times, Selma AL, October 4, 1899, pg. 3. newspapers.com.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Asheville Daily Gazette, Asheville, NC, August 26, 1899, pg. 5. -newspapers.com

[25] “Mrs. W. S. Monk and children of Selma, Ala. Are among the recent arrivals from the south. Mrs Monk is visiting her father, S. D. Holt, Pearson drive, and expects to spend the remainder of the summer here.”-Asheville Citizen-Times, Asheville, NC, August 6, 1899, pg. 4. -newspapers.com

[26] “Home From Selma”, Asheville Citizen-Times, October 7, 1899, pg. 1. -newspapers.com

[27] Asheville Citizen-Times, October 14, 1899, pg. 2. -newspapers.com

[28] Asheville Citizen-Times, January 1, 1900, pg. 1. -newspapers.com

[29] See: Asheville Citizen-Times, March 16, 1900, pg. 4.; and also, Asheville Citizen-Times, April 6, 1900, pg. 4. -newspapers.com –

[30] Asheville Citizen-Times, May 2, 1900, pg. 8. -newspapers.com

[31] Ibid.

[32] 08/17/1900 (rec-d 09/06/1900) Samuel D. & Catherine V. Holt to Eliza W. Gillis MONTFORD AVENUE Db. 111/596. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[33] “JUDGE CALVIN GILLIS: Passed Away Yesterday At His Home In This City”, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 11, 1900, pg. 1. -newspapers.com (Note “His Home In This City” was at 167 North Main Street, now Broadway Avenue).

[34] 11/19/1900 (rec’d- 11/20/1900) Samuel D. & Catherine V. Holt to Agnes R. Wilson GAY STREET Db. 119/1. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[35] Asheville Daily Gazette, Asheville, NC, December 1, 1900, pg. 8. -newspapers.com

[36] The Selma Times, Selma, AL, July 24, 1900, pg. 2. -newspapers.com

[37] “A NEW INDUSTRY ESTABLISHED HERE: The Raising of Belgian Hares For Market”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 19, 1900, pg. 1. -newspapers.com.

[38] “MR. HOLT LEAVES ASHEVILLE”, The Asheville Weekly Citizen, November 8, 1901, pg. 3. -neowspapers.com

[39] “Mrs. L. A. Johnson Dead”, Asheville Daily Gazette, Asheville, NC, April 1, 1902, pg. 5. -newspapers.com

[40] “Burton Tickled With Partner”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 13, 1927, pg. 40. -newspapers.com. This partnership remained until the death of S. D. Holt in 1914, at which time Burton acquired the entire business. In 1927, Burton took his son on as a partner and changed the name of the firm to S. P. Burton & Son.

[41] Asheville Citizen-Times, December 31, 1903, pg. 5. -newspapers.com

[42] 12/08/1906 S. D. & Catherine V. Holt to J E Rankin (party of the second part); J. M. Seigler & J. B. Seigler (parties of the third part) [D/T] Db. 64/598. “Sum of Two Thousand ($2,000) dollars…”. “…intending to include all the land in which said S. D. Holt is now building a dwelling.”

[43] “What Is a Deed of Trust?” By Matt Ryan Webber Updated August 31, 2022-from: https://www.investopedia.com/deed-of-trust-definition-5221503

[44] 12/08/1906 S. D. & Catherine V. Holt to J E Rankin (party of the second part); J. M. Seigler & J. B. Seigler (parties of the third part) [D/T] Db. 64/598. “Sum of Two Thousand ($2,000) dollars…”. “…intending to include all the land in which said S. D. Holt is now building a dwelling.”

[45] “A Bunch of Andrews Heating contracts”, The Improvement Bulletin, Volume 34 No. 18 (March 30, 1907), (Minneapolis, MN: Chapin Publishing Company, 1907), pg. 21. Digitized: Nov 18, 2014 by: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. https://books.google.com/books

[46] “SAMUEL D. HOLT DIES SUDDENLY AT HIS HOME HERE”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 11, 1914, pg. 1. -newspapers.com

[47] “WILL OF S. D. HOLT FILED THIS MORNING”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 30, 1914, pg. 2. -newspapers.com

[48] Asheville Citizen-Times, October 23, 1917, pg. 6. -newspapers.com

[49] 07/25/1921 Ellerbee Holt Fowler to Harry S. Webster WEST CHESTNUT STREET Db. 247/23. “THAT WHEREAS, Samuel D. Holt, late …by his last will and Testament, devised his home place, known as No. 162 W. Chestnut Street in the City of Asheville to his widow Katherine V. Holt for life with the remainder in fee to his daughter Ellerbe Holt Fowler.”

[50] 01/20/1922 Harry S. Webster to Elsie Boling Webb S SIDE W CHESTNUT ST Db. 254/390. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[51] Info from tree posted by “Reevesturbyfill” on ancestry.com. – https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/77867528/person/240191028395/story?_phsrc=PnA20&_phstart=successSource

[52] Asheville Citizen-Times, November 4, 1964, pg. 20. -newspapers.com

[53] Asheville Citizen-Times, March 20, 1987, pg. 27. -newspapers.com

[54] 08/06/2021 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints to James Blanding Holman & Susannah Knox ASHEVILLE TWP PARCELS PB 20/63 Db. 6103/1484.