by Dale Wayne Slusser

As if finding a stash of empty, lidded, stacked liquor bottles behind a basement wall, and finding a shoe that was intentionally placed inside of a plastered wall, were not mysterious enough for the homeowners of 191 Murdock Avenue, tracing the history of the ownership of the house (especially during its first two decades) proved to be just as mysterious. Missing deeds, misleading recitals, as well as numerous foreclosures and courthouse sales made following the change of title difficult and, dare I say, “mysterious”. The other conflicting mystery was that at first, following the chain of title (historical record of home’s ownership), it appeared that the house may have been built as a spec house, YET the quality of the finishes and special features of the 1920’s house suggested that the house was more likely built as someone’s custom “dream house”. Tracing the history of 191 Murdock is another lesson for me (and you) to show the importance (and oft-times necessity) of getting into the “weeds”, the nitty-gritty details, like following the deeds and deeds of trusts, along with comparative analysis of primary sources such as city directories and newspaper articles to unlock the history of a property. But also, the history of 191 Murdock, besides being a great lesson in the methods of historical researching, is also a great story featuring the famous, the not so famous, and even the infamous! It starts with an array of the famous.

Pharmaceutical magnate Edwin Wiley Grove, who started as a small-town pharmacist in Paris, Tennessee, by the 1880’s had become a millionaire based on two products-Grove’s Tasteless Chill Tonic and Grove’s Bromo-Quinine tablets, both of which featured the anti-malarial drug, quinine. Both products were widely marketed, particularly in the South where quinine had long been used as an antimalarial drug. In 1897, Grove came to Asheville for the healthy climate, hoping it would cure his bronchitis and chronic hiccups! It must have worked, for soon Grove had begun to invest his time and money into making Asheville an alluring destination for the rich and famous. In 1904, Grove began developing a new high-end residential development in the northeast section of Asheville on the northwest side of Charlotte Street, surrounding the Asheville Country Club which he had just recently acquired. Grove’s new development, humbly named “Grove Park”, catered to high-class homeowners. An early advertisement even promised: “You are also protected from undesirable houses being built near to you!” These protections included setting a minimum house cost, established building setbacks, and requiring all building plans to be reviewed and approved by the developer. The main throughfare of the new development was named Edwin Place. Edwin Place started at the west margin of Charlotte Street and went west for a few blocks, and then oddly turned northwest just before its end. At its end was the intersection of Evelyn Place (named for Grove’s daughter) and a row of lots along the northwest margin of Evelyn Place. In 1913, E. W. Grove built the “Grove Park Inn” on Sunset Mountain overlooking his new residential development and the Asheville Country Club. The new Inn began attracting the rich famous, such as Harvey Firestone, Thomas Edison, and Henry Ford, just to mention a few.

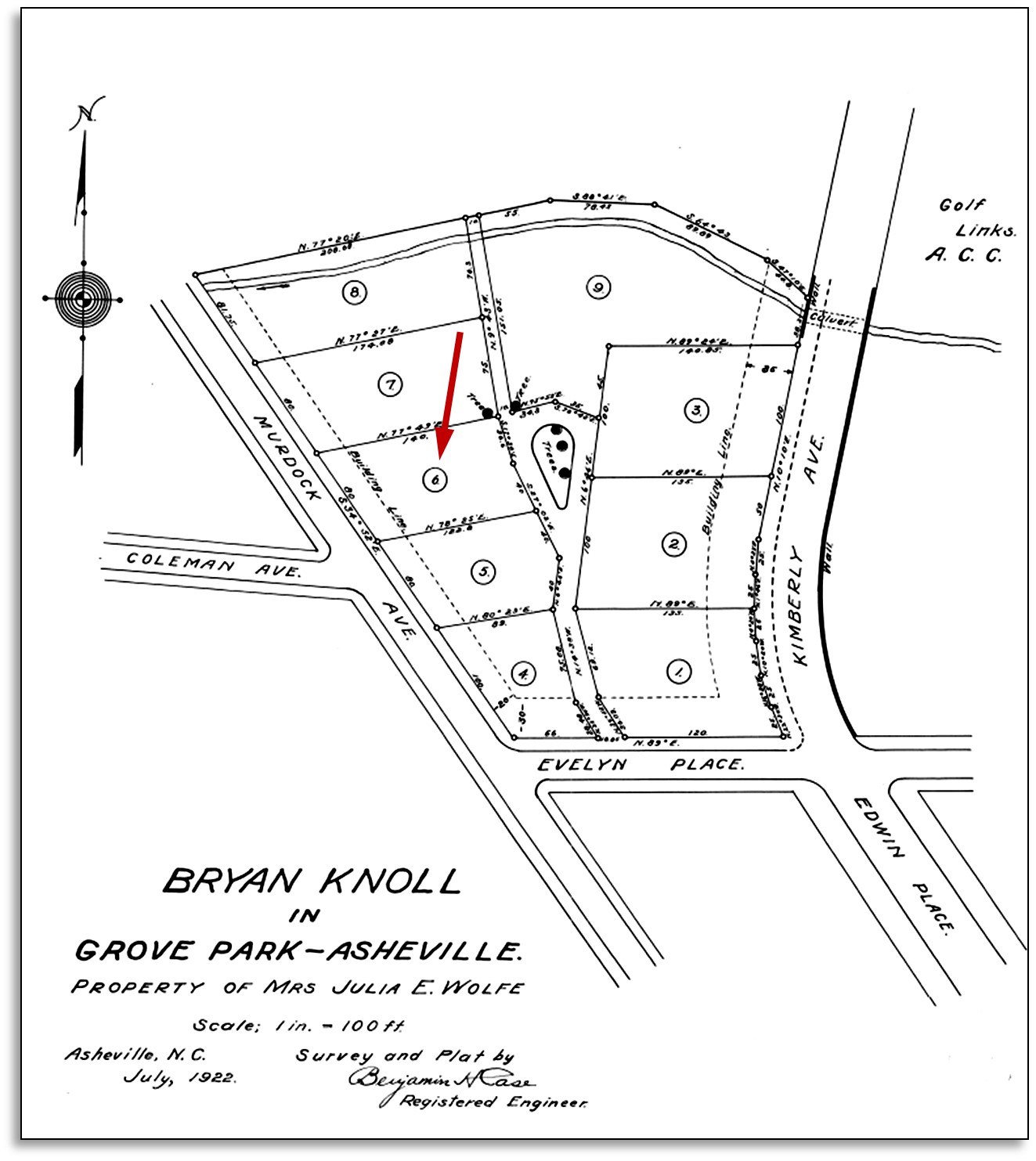

In 1917, Grove sold a block of lots on Evelyn Place, opposite the end of Edwin Place, to the then nationally well-known lawyer, orator and politician, William Jennings Bryan.[1] Bryan had been a frequent visitor and “summer-home” owner for a number of years. In fact, in 1913, Bryan who was then Secretary of the State, came down from Washington DC to be the keynote speaker at the grand-opening of the Grove Park Inn. Bryan hired local architect, Richard Sharp Smith to design a new house, which Bryan then built at 107 Evelyn Place. Just a few years later, in 1921, E. W. Grove purchased the former Kimberly family lands to the northwest of Grove Park. It was then that Grove decided to extension Edwin Place, into a new street (running northwest), originally called Blue Ridge Avenue, but later changed to Kimberly Avenue. The extended street went directly through the Bryan property, splitting it in two, with the house on the north side of new the street and his remaining property, which had been nicknamed “Bryan Knoll”, on the south side of the new street.

In 1922, Bryan and his wife sold Bryan Knoll to Julia E. Wolfe a local boarding house owner, and real estate developer. [2] Julia was soon to be famous as the mother of Thomas Wolfe, a famed early twentieth-century novelist. With the sale of the Bryan Knoll lots, Julia Wolfe agreed as a developer to the deed restrictions that came with the property, in order that her development would be compatible to Grove Park. Among these deed restrictions were the required minimum house sizes, based on their costs. For Lots. 1,2, & 3, the deed restricted that any “residence shall not cost less than $10,000” and for the remaining lots (Lots. 4,5,6,7,8, &9) any “residence shall not cost less than $5,000.”[3] The house that would be built at 191 Murdock was on Lot 6.

Julia Wolfe’s “Bryan Knoll” developed slowly, with the first of the lots being sold in 1922, and then just two lots in 1923, before selling the fourth lot, Lot 6, to Rebecca Huvard in 1925.[4] Following the chain of title, without looking at the accompanying deeds of trust, showed that A. J. & Rebecca Huvard then sold the lot in November of 1926 to W. B. Nixon, a builder who was building a number of houses across the street along Murdock Avenue. Just the seemingly short time between the property transfers, combined with the Huvards selling the lot subject to the original development restrictions, seemed to indicate that Nixon had purchased the lot without a house. Then to add to my misassumption, the subsequent deed that I found seemingly showed that Nixon had held on to the property until 1948.[5] Knowing that Nixon was a builder/developer, I assumed that Nixon had built the house as a spec house/rental investment property. To add to my misassumption (which then was merely an assumption), a search the city directories showed that “191Murdock” did not show up until 1928, and was then being occupied by J. B. Ross, assumingly a renter? But then I went to visit the house and its new owners, and discovered that my quickly searched chain of title, not only had vast holes in it, but it had led me to wrong assumptions.

Upon visiting the house, I quickly discovered, as had the new homeowners, that the level of detail and craftsmanship in the 1920’s house pointed to the house having been built as a custom home, and certainly not as a “spec house”. Also, upon visiting the house, I discovered that one of the homeowners, Kelledy, had not only already done extensive research on the history of the house, but to my chagrin, I discovered that she had found various deeds that indicated that the property had sold to numerous owners between 1927 to 1948-the period in which my “quick search” seemed to show that the property was owned by W. B. Nixon. However, since my initial assumption that Nixon had built the house as a spec house, I had come to the revised assumption that perhaps A. J. Huvard had started building the house, but then had fallen into financial troubles and had to sell the house, either before it was completed or just after. I purported this assumption to Kelledy. However, not only was my revised assumption based on superficial evidence but discovering that I had missed a number of deeds in my title search, it became evident that a deeper dive into the deeds and other primary sources was necessary to solve this conundrum (aka: mystery).

Returning home, I immediately began to search for the deeds that I had missed, as I confess that my vanity wanted to find them on my own before Kelledy sent me the missing deeds. Of course, I had to acknowledge that if Kelledy had not told me of the other deeds, I most likely would have continued down the wrong path. Suffice it to say that I did find the missing deeds, though with difficulty, as during that period the house not only had a couple of foreclosures, but even was once purchased at the courthouse by a “substitute buyer”, who immediately then “assigned” the deed to the real buyer, so following the names and transfers was complicated and confusing. And although finding the missing deeds did not negate my assumption that A. J. Huvard may have had the house built, neither did they provide much supportive evidence either.

But before I went any further in my deed searching, I had to find out who this “A. J. Huvard” was and what other connections might he have had to the possible building of the house at 191 Murdock Avenue. Using ancestry.com to locate censuses, marriage and death records, and other public records, as well as performing an extensive search of newspapers.com, the story of A. J. Huvard began to reveal itself.

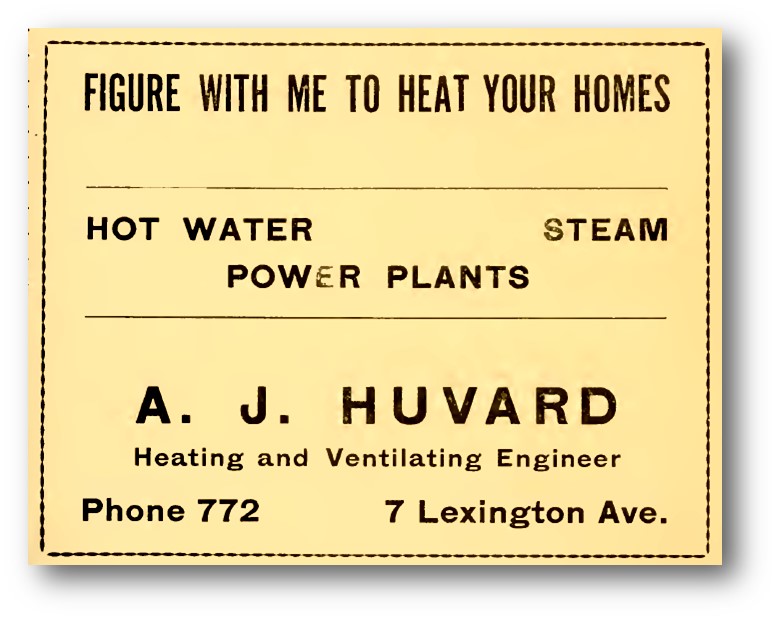

“A. J. Huvard” was Adolph Julius Huvard, who according to the information he told to the 1920 Census taker,[6] was a Russian born immigrant who emigrated to the US in 1895 and became a naturalized citizen in 1903. According to information that he had given at the birth of his second son, he was born in Paris, France.[7] Little is known (from the public records) of his life prior to 1911. But by 1911, he was living in Chattanooga, TN and working as a “steamfitter” for Lookout Steam Heat & Supply Company. By 1912, he had moved to Atlanta, GA and was married to “Emma”, and still listed as a steamfitter. By 1914, A. J. Huvard was living and working in Asheville, as a 33 year old (unmarried) man, and was becoming active in the local Jewish community activities, such as the Pioneer Club, which was advocating for the establishment of a “Y. M. H. A.” (Young Men’s Hebrew Association) in Asheville.[8] In 1915, he opened his plumbing business in the basement of a small row-house-type storefront at 7 E. College Street (the site is now part of the Akzona/Biltmore Building on Pack Square and College Street). Also in 1915, after first boarding at 34-1/2 Broadway, Huvard purchased a small bungalow at 4 Austin Street as his residence.[9]

In May of 1916, the Asheville Times, in an article titled, “BUILDING ACTIVITY ON A BOOM HERE”, reported that, “Men in touch with the building business say that prospects for a record year in the construction of Asheville homes and business houses are brighter than any other period within the past eleven years. All improvements mentioned [in the article] will cost approximately $65,000 and a large number of laborers, architects and other business firms will share in the distribution of the money expended.”[10] I suspect that this building boom is what first attracted A. J. Julius to Asheville, and of course we now know that this building boom kept growing into the 1920’s. In fact, in this same article, it was also reported that “Dewey & Hurvard, plumbers and heaters”, were to occupy the first floor of a two-story brick building that was then being erected at the corner of Carolina Lane and Woodfin Street by builder/developer J. T. Bledsoe. In the 1917 Asheville City Directory, A. J. Huvard advertised himself as a “Heating and Ventilating Engineer”, with his office on Carolina Lane at the corner of Woofin street, specializing in hot water and steam heating systems. Today we would call Huvard an HVAC Mechanical Engineer, but back then he was known as a plumber or “steamfitter”. 1917 was also the year that A. J. Huvard was officially engaged to Rebecca Goldberg, the daughter of Max and Anna Goldberg of Asheville.[11] Although the announcement said that the wedding was to take place “next Fall”, World War 1 intervened. The 3rd draft registration, for all men aged 18 to 45 years came on September 12, 1918, and correspondingly, that is the day that Adolph Julius Huvard signed his draft card. Apparently, he was already working for the “W.S.A.” as an “erecting engineer” at “Azalea”.[12] Azalea, just east of Asheville was the site of the Federal government’s new tuberculous hospital, being constructed to treat the many wounded soldiers with lungs problems, mostly caused due to exposure to “mustard gas”. As Asheville was already the center for tubercular care, because of its fresh “healthy” climate, the new hospital was a good fit. Although a consortium of Asheville businessmen had lost the bid to construct the new hospital to an Atlanta contractor, [13] they nonetheless arranged that the majority of the workman hired for the construction were to come from Asheville. [14] They even established a shuttle service from Asheville to Azalea for the workman. The massive hospital complex required the construction of a huge central hot water/steam heating system, which must have been what Huvard was involved with as an “erecting engineer.”

1917 was also the year that A. J. Huvard was officially engaged to Rebecca Goldberg, the daughter of Max and Anna Goldberg of Asheville.[11] Although the announcement said that the wedding was to take place “next Fall”, World War 1 intervened. The 3rd draft registration, for all men aged 18 to 45 years came on September 12, 1918, and correspondingly, that is the day that Adolph Julius Huvard signed his draft card. Apparently, he was already working for the “W.S.A.” as an “erecting engineer” at “Azalea”.[12] Azalea, just east of Asheville was the site of the Federal government’s new tuberculous hospital, being constructed to treat the many wounded soldiers with lungs problems, mostly caused due to exposure to “mustard gas”. As Asheville was already the center for tubercular care, because of its fresh “healthy” climate, the new hospital was a good fit. Although a consortium of Asheville businessmen had lost the bid to construct the new hospital to an Atlanta contractor, [13] they nonetheless arranged that the majority of the workman hired for the construction were to come from Asheville. [14] They even established a shuttle service from Asheville to Azalea for the workman. The massive hospital complex required the construction of a huge central hot water/steam heating system, which must have been what Huvard was involved with as an “erecting engineer.”

A.J. and Rebecca finally married two years after being engaged, at the Goldberg home on Chestnut Street in Asheville on June 29, 1919.[15] They moved into a rented house at 161 S. Liberty Street (no longer standing) and Julius was employed in (or owned?) a “mens furnishings” business at 11-1/2 Biltmore Avenue. An odd business for an experienced plumbing and heating engineer, I suspect that post-war construction was at a low ebb in 1919 and 1920. But soon, post-war building began, which for Asheville would become a huge building boom during the “roaring” 1920’s. In 1921, A. J. Huvard partnered with a fellow plumber and veteran Lindsey Duncan Campbell to form “Asheville Plumbing and Heating, Inc.”, with Campbell directing the plumbing work and Huvard directing the heating work.[16]

By 1925, Huvard was so involved in Asheville’s building frenzy, that in conjunction with his plumbing and heating contracting business, he also formed the “Asheville Specialty & Supply Company” to sell heating and plumbing supplies, as well as the “Carolina Oil-O-Matic Company”, as distributors of the Williams Oil-O-Matic heating systems. It was during this boom time that A. J. and Rebecca, it seemed, decided to build their “dream house” for their growing family, which included a son, Malcom born in 1922 and a soon to be born son (they named Allen Bruce). To this end, the Huvards purchased a choice hillside lot on Murdock Avenue, with views to the west.[17]

With the assumption that the Huvards may have had the house built, it was time to seriously and thoroughly search out and examine all of the deeds of trusts, especially those associated with early property transfers. I will not bore you with all of the deeds of trusts and their contents, however I will highlight a few which did reveal vital clues to solving our mystery. The first clue was found in a deed of trust, signed on December 2, 1925, the same day as the Huvards signed the transfer deed from Julia Wolfe. This deed of trust was for $8,000, borrowed from the Central Bank & Trust Company. [18] Although this may have indicated that Huvard was getting a mortgage on a finished house, it also may have been a clue that he was getting a construction loan to finance building a new home. But over the course of a few months, A. J. Huvard obtained at least two subsequent deeds of trusts,[19] culminating in a deed of trust in May of 1926, for $12,500, again from the Central Bank & Trust Company.[20] This progressive financing suggested that Huvard was financing an active project, that may have been initially estimated to cost $8,000, but as most projects do, was experiencing costs over-runs. This might explain the high-end features that were used in the house, such as the elaborately embossed plaster walls, the phone niche to house a “modern” telephone, a modern glazed tiled fireplace surround, colorful tiled baths, and steam shower.

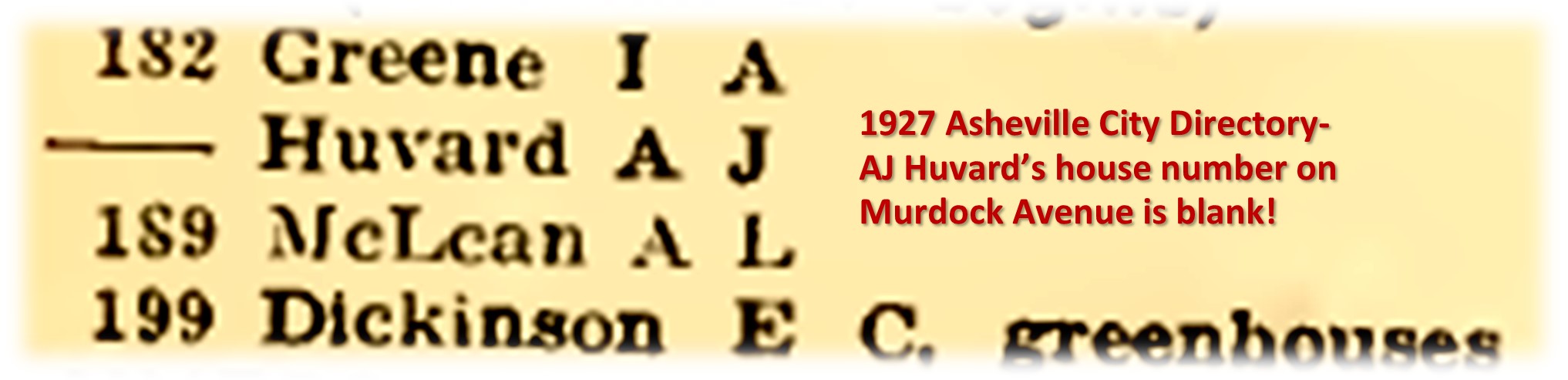

So, although Huvard’s progressive financing suggested that he was building a custom home, the city directories were confusing. In 1924, 1925, and 1926, the city directories listed the Huvards as residing at “1 Virginia Avenue”, which comparing with the Huvard’s multiple deed transactions during those years, confirmed that they had purchased that house. That made sense as the house was literally just down the street at the corner of Murdock Avenue and Virginia Avenue (now called Norwood Avenue), within sight of 191 Murdock to keep an eye on constrcution. And then the 1927 city directory revealed an important, though again confusing clue. In the names listing, A. J. & Rebecca Huvard are listed as living at 189 Murdock Avenue. However, in the same directory in the street listing section, A. J. Huvard is listed as living on Murdock, but he is listed at an unnumbered address between 182 and 189 Murdock.[21] Comparing the 1927 directory street entry with the 1928 directory listing shows that not only is A. L. McLean shown still living at 189 Murdock (as he was listed in 1927) but that 191 Murdock is shown for the first time, and lists its occupant as J. B. Ross, who I knew from the deed search as having been a subsequent owner after the Huvards.

Now, it must be understood that much of a specific year’s directory information is gathered the year before. Which means that the search of the 1927 city directory shows that indeed A. J. Huvard was the first owner/occupier of the house at 191 Murdock, probably for a few months during 1926. But then in November of 1926, the Huvards sold the house to builder W. B. Nixon.[22] Walter Blair Nixon was an Asheville builder/developer who among numerous projects at the time, was developing and building houses across the street along Murdock and Annandale Avenues, as well as developing lots and building houses and apartments further up Murdock Avenue at Lennox Street, just off of Hillside Street.[23]

But why did the Huvards sell the house so shortly after it was finished? And why to a builder? The answer to the first question became obvious when I found the following announcement in the March 4, 1927 edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times: “Voluntary petition in bankruptcy was filed yesterday in the Federal Court by A. J. Huvard, trading as the Asheville Plumbing and Heating Company”.[24] Although local papers would not acknowledge it at time, looking back, historians have confirmed that like Florida, Asheville’s real estate frenzy crashed in 1926. A. J. Huvard was in double jeopardy by 1926, as not only had he dabbled in the frenzied real estate buying and selling, but also his entire businesses were dependent on the building trades, and when building slowed-down, his businesses slowed down as well. Combine all of that with the fact that much of his financing for his business and real estate ventures was based on borrowed money, it’s no wonder that he went under. Unfortunately, he was not alone, as thousands were in the same trouble, all of which eventually ushered in the bank failures of 1929 that led to the “Great Depression” of the 1930’s.

Why did Huvard sell his newly finished house to a builder? Although I don’t know for sure, I suspect that Nixon may have been the builder of Huvard’s dream house, and perhaps he bought it from Huvard in lieu of Huvard not being able to pay Nixon’s bill? Not only did Nixon buy the property, but in so doing he also assumed a deed of trust for $12,500 dollars, which the Huvard’s had taken out against the property in 1926.[25] Then three months later, in January of 1927, Nixon borrowed $4,380.84 against the property.[26] Nixon’s deed of trust also gives us a clue that a house was on the property, as he was required to carry fire insurance on the house “so long as the debt hereby secured remains unpaid”.[27] Just three months later, Nixon sold the house along with both his $4,000 debt as well as Huvard’s $12,500 debt to J. B. & Margaret Ross.[28] The numbers work out, as according to the 1930 census for J. B. Ross, who still owned 191 Murdoch, the home was then valued at “$20,000”[29], which means that Nixon made a good profit on the sale.

J.B. Ross was Jacob Boyd Ross, Jr. who had moved to Asheville from South Carolina in 1926. Ross, like his father, was a road contractor. He moved to Asheville to accept a position as superintendent of the Asheville Construction Company, and for the health of his wife. Unfortunately, Ross and his family only lived in the 191 Murdock Avenue house for three years, until the death of Mrs. J. B. Ross in 1930,[30] at which time Ross moved back to South Carolina. With the death or his wife and the 1929 crash it’s not surprising that Ross defaulted on the $12,500 Central Bank loan to A. J. Huvard, which Ross had assumed when he purchased the house.

1930 was also a tragic year for the Huvard’s, who were then living at 10 Carolina Avenue (now 4 Ramoth Road), in a small bungalow in Norwood Park, just up the street from their dream house. In November of 1930, A. J. Huvard, suddenly died as a result of a cerebral hemorrhage,[31] leaving Rebecca and two sons, Malcom and Alan. Huvard had managed to keep open or re-opened the Asheville Plumbing business, despite the bankruptcy of 1927. Two weeks after his death, Rebecca bravely announced that “ASHEVILLE PLUMBING AND HEATING WILL continue at the old location, 3 Court Place, under new management of Mrs. A. J. Huvard.”[32] But apparently the business was doomed due to the ensuing economic depression. Rebecca Huvard soon got a job working for Pollock’s Store in downtown Asheville, which in 1937, merged with the Butler Shoe Store chain. Rebecca and her sons eventually moved to Atlanta when she accepted a position at a branch store of Butler Shoes.

So, by 1930, the 191 Murdock Avenue house was in the hands of the Central Bank & Trust Company, and vacant. But in November of 1930, the bank sold the house to Joseph H. Gilmore at a Courthouse sale.[33] Joseph Gilmore owned the house for four years but appears to have only lived in it a couple of years, before selling it in 1934 to dentist, Dr. Maxwell Ellis Hoffman.[34] The Hoffmans and their five children lived in the home for 10 years. It was the scene of numerous family events such as college send-offs, engagements, and weddings. The Hoffmans sold the house in 1944 to William C. & Bessie Miller,[35] and moved to Lake View Park.

By the time that William Cassada Miller bought the house at 191 Murdock in 1944, Miller already had a reputation as a “proprietor” of what the British call pubs, but what we Americans call “beer joints/bar”. Miller had already been associated with the “Smoker’s Corner”, the “Do Drop Inn”, and the “Home Folks Sports Center” (an early sports bar?). Miller also already had a lengthy police record, having been arrested and fined multiple times for “operating gambling devices”. In 1942, “two retailers” in Asheville were denied permits to sell beer, Smoker’s Corner and Do Drop Inn, both of which were affiliated with Miller. The recommendation to deny permits to these two specific “retailers” was made to the city tax office by “police Chief Dermid.”[36]

A few months after purchasing the house, W. C. Miller opened the “Casa Loma Restaurant” “atop the Plaza Theater” at Pack Square in downtown Asheville. Unlike his other establishments, the Casa Loma was a dinner/supper club restaurant. The grand opening on August 11, 1944 was so well attended, that the restaurant had to apologize for not being able to serve all who had come out, saying that although they had expected a large crowd that “it looked as all of Asheville had planned to dine here for our opening”![37] The Casa Loma seemed like a success. Perhaps on the strength of that success, in 1945 W. C. Miller, in partnership with J. O. “Buck” Buchanan purchased property from the Hildebrand estate on the west side of Tunnel Road to build a new restaurant/diner. Named “The Drive In”, the new establishment opened in 1946 with J. O. Buchanan as the manager/operator. Old-time Ashevillians would recognize the restaurant by its later name, “Buck’s Drive In”.

Things seemed to be looking up for W. C. Miller, at the beginning of 1947. In January of 1947, W. C. “Casty” Miller signed an agreement with William Orr to become a third partner in The Drive-In restaurant.[38] But maybe not-In February of 1947, W. C. sold the Casa Loma restaurant to his son Bill C. Miller, Jr.[39] Then in May of 1927, Bill C. Miller, Jr. was arrested at the Casa Loma for unlaw possession of whiskey.[40] It was allegedly unlawful because the whiskey was found in a hamper at the Casa Loma, and because prior to 1977 restaurants were not allowed to sell or serve liquor, other than beer or wine. Bill, Jr. was later acquitted as he claimed that the whiskey was “there for his own use and not for sale”, which was supported by the fact that at the time of arrest the restaurant was not open for business.[41] In June of 1947 William and Bessie separated and the next month filed a legal separation agreement.[42] In the deed of separation, the couple agreed that Bessie would get all three houses: 191 Murdock Avenue, 16 Albemarle Road, and the house in Miami, FL, and that in order to transact the transfer they would sell the properties to their son Bill, Jr. who would then sell them solely to Bessie. Then in the first week of November it was reported that William C. Miller was charged in federal court “for promoting an illegal lottery on a government reservation”, allegedly at the V. A. Hospital in Oteen, East Asheville.[43] The following week Miller was convicted in U. S. District Court of operating a lottery on government property and of unlawful possession of gambling devices, and was sentenced to “six months in jail, suspended on probation for two years and payment of a fine of $200.”[44]

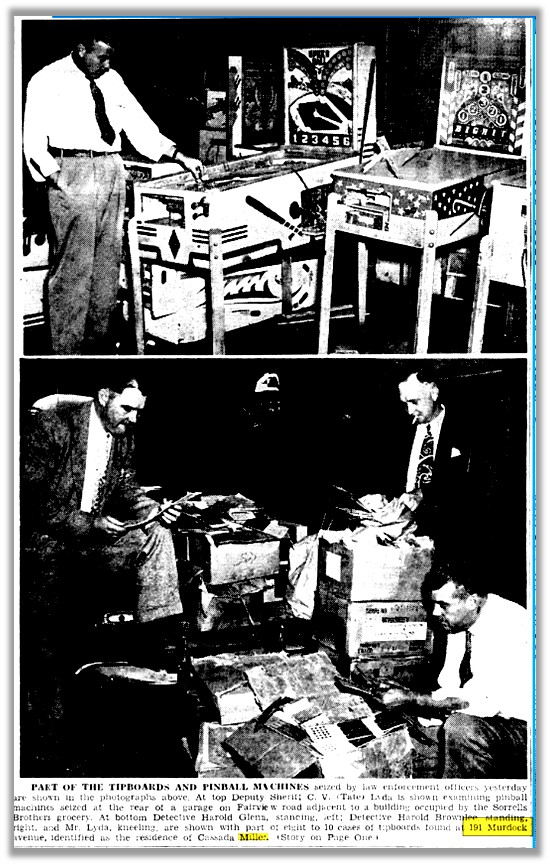

Although Bill C. Miller, Jr. did sell the three houses to Bessie as per the 1947 separation agreement,[45] the 1948 Asheville Directory shows that William and Bessie were still living together at 191 Murdock, and that William was working at the “Brown Derby”. In August of 1948, the Brown Derby was one of four establishments that Judge Zeb Nettles ordered “padlocked” as part of law-enforcement’s “drive against gambling and booze joints in the city and county”.[46] To make matters worse, Miller was the operator of the Brown Derby. Not surprisingly, two weeks later, the police raided the house at 191 Murdock Avenue, and found a stash of 364 baseball lottery boards, 1,943 tipboards, and four cardboard boxes of accompanying papers stubs.[47] Could all this illegal activity explain the stash of empty, lidded liquor (bourbon whiskey) bottles that the current owners of 191 Murdock Avenue discovered hidden behind a basement wall? Just possibly-although further investigation would be needed, such as trying to identify the bottles and their dates of manufacture.

Despite the Separation Agreement of 1947, and the accompanying transfer of the property from Bill, Jr. to Bessie Miller, curiously both Bessie and William C. Miller signed the deed when they sold the house at 191 Murdock Avenue to William and Helen Piver in 1949.[48] As I was initially tracing the deeds back when first developing the chain of title for this property, there was a “recital” in this deed which referenced a 1948 deed “to Bessie M. Miller from W. B. Nixon” in “book 668 at page 300”[49], indicating that W. B. Nixon was the immediate previous owner. So naturally I went straight to look for W. B. Nixon as the grantee (buyer), which led me back to 1926, when W. B. Nixon purchased the house from A. J. Huvard. By doing so, I had completely missed twenty years of deeds between 1926 to 1949. The lesson learned was to not make assumptions and READ the deed carefully. If I had done that, I would have noticed that the 1948 Nixon deed was merely a “quit claim” deed, saying that Nixon no longer had any interest or claim on the property. So although the recital was correct in “reciting” the previous property transfer, it was misleading as it gave the impression that Bessie Miller had purchased the property from Nixon. A quit claim deed is used to remove apparent defects in the chain of title without the time and expense of litigation, and although the quit claim transfers a former owner’s interest, it’s not always the immediate previous owner.

The drama and eventful first two decades of the house at 191 Murdock Avenue ended in 1949 when the Pivers bought the house, which became their family home for over thirty years. In 1983, following the death of Helen Piver (her husband had died in 1978), the Piver heirs sold the family home.[50]

Two or three families owned the house after 1983 until 2021, when Kelledy Francis and Jon Claude Bieschke purchased the house at 191 Murdock Avenue. The couple immediately began restoring the house to its original glory, by first cutting back the weeds and brambles in front of the house that had almost completely hidden the house from the street. Then they turned the former basement servants’ rooms into a long-term rental unit, and turned the former two-car garage into an attractive home-stay short-term rental. These income-producing units helped to make the house restoration both possible and feasible. The interior of the house was restored, retaining the original features such as the embossed plaster walls, hardwood floors and tiled fireplace-surround. Most of the original light fixtures were cleaned and reused or were replaced with period fixtures. The kitchen was updated, and although the bathrooms were spruced up, they still retained their original tiles and fixtures. Of course, since the house had been built by a plumbing contractor, it had high-quality original fixtures.

All the mysteries of the house at 191 Murdock Avenue have been solved (perhaps not completely). Oh, what about the “shoe in the wall” mystery? Most likely the shoe was placed in the wall by the Huvards when the house was constructed. Historians have gathered ample documentation of instances of shoes being found imbedded in house walls or in fireplace cavities. Although it seems to have been a common practice, the theories for the reasons why are varied. However, the most widely accepted theory is that “people did and still do put a shoe in the walls or foundation of a building, probably in order to ward off bad luck or bring good luck.”[51] In old world traditions shoes have symbolized good luck, hence the tying of old shoes to the bumper of the car of the newlyweds driving off on their honeymoon!

As an epilogue to the mystery of 191 Murdock Avenue, I must tell you that I have traced down two descendants of A. J. Huvard, two living grandsons. By the way, this is an effective tool to use when researching a house or building’s history – to track down former owners or their descendants, using obituaries and online directories to find them. The grandsons confirmed our suspicions by telling us that the “family lore” was that the Huvards had built their dream house, but then went “bust” and had to sell it. In fact, one of the grandsons told us that one time, years later, his grandmother, Rebecca Huvard, had his father (her son) drive her to Asheville to show him the house and tell him the story. The restored house at 191 Murdock Avenue still sits proudly above the street, and again it is not only a showpiece as it was first intended, but it is again someone’s “dream house”!

Photo & Image Credits: (Note: All cropping and captions by author)

Photo of 191 Murdock Avenue- Photo by Dale Slusser, February 2023.

Bryan Knoll Plat- 07/01/1922 Julia E. Wolfe PLAT BRYAN KNOLL IN GROVE PARK Db. 154/215. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Portrait of Adolph Julius Huvard– Courtesy of Todd Huvard, Clayton, NC.

A.J. Huvard Advertisement- Asheville, North Carolina City Directory, Volume XV, 1916. (Asheville, NC: Piedmont Directory Company, Inc., 1916) page 12. – https://lib.digitalnc.org

A.J. & Rebecca Huvard Portrait- Courtesy of Todd Huvard, Clayton, NC.

Oil-O-Matic Advertisement- Asheville Citizen-Times, February 22, 1925, page 14. – newspapers.com

Street listing for A. J. Huvard- Asheville, North Carolina City Directory, Volume XXVI, 1927 (Asheville, NC: Piedmont Directory Company, Inc., 1927), page 1025.- https://lib.digitalnc.org

Asheville Heating & Plumbing Announcement- “THE ASHEVILLE PLUMBING AND HEATING CO.”, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 2, 1930, page 32. -newspapers.com

1948 Raid at 191 Murdock- “Gambling, Lottery Equipment Seized”, Asheville Citizen-Times, September 3, 1948, page 2. -newspapers.com.

Photo of Ancient Age Bourbon Whiskey Bottle- Courtesy Kelledy Francis, Asheville, NC

[1] 11/01/1917 (rec’d-12/15/1917) E. W. & A. G. Grove to William Jennings Bryan LOTS 18 & 20-24 PART 19 BLK E BK 154 P 171 Db. 215/531. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[2] 06/30/1922 (rec’d-08/25/1922) William Jennings & Mary B. Bryan to Julia Wolfe MURDOCK AVENUE Db. 259/276.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[3] 10/28/1922 E. W. & A. G. Grove to Julia E. Wolfe AGREEMENT Db. 261/576. “References Plat 154/171”- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[4] 12/02/1925 (rec’d-12/04/1925) Julia E. Wolfe to Rebecca G. Huvard LOT 6 BK 154 P 215 Db. 323/130. “subject to restrictions…”- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[5] 11/29/1948 W. B. & Anne Kroll Nixon to Bessie M. Miller MURDOCK AVE Db. 668/330.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[6] See 1920 Census Records- https://www.ancestry.com

[7] Birth Certificate for: Malcom Conway Huvard, born in Asheville, NC on December 5, 1922-accessed via familysearch.org

[8] “Y. M. H. A. IS AIM OF PIONEER CLUB”, Asheville Gazette News, November 28, 1914, page 2. -newspapers.com

[9] 09/01/1925 (rec’-d 10/27/1915) J. A. & Eva Sinclair to A. J. Huvard LOT 1 BK 198 P 28 AUSTIN AVENUE Db. 204/39. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[10] “BUILDING ACTIVITY ON A BOOM HERE”, Asheville Times, March 27, 1916, page 2.- newspapers.com

[11] Asheville Citizen-Times, April 29, 1917, page 6. – newspapers.com

[12] Adolph Julius Howard in the U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 -ancestry.com

[13] Asheville Citizen-Times, February 26, 1918, page 1. – newspapers.com

[14] “AZALEA JOB WILL BE STARTED IN A FEW DAYS”, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 20, 1918, page 9. (Excerpt: “Preference is being given Asheville union men in the assignment of jobs, in line with the agreement of the contrctors with the representatives of the Central labor union.”) -newspapers.com

[15] Asheville Citizen-Times, July 4, 1919, page 6. – newspapers.com

[16]11/04/1921 A. J. Huvard & L. D. Campbell” PARTNERSHIP Db. 247/349. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds. See also advert: Asheville Citizen-Times, September 27, 1921, page 3. -newsppapers.com

[17] 12/02/1925 (rec’d-12/04/1925) Julia E. Wolfe to Rebecca G. Huvard LOT 6 BK 154 P 215 Db. 323/130. “subject to restrictions…”- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[18] 12/02/1925 (rec’d-12/04/1925) A. J. & Rebecca G. Huvard to Central Bank & Trust [D/T] MURDOCK AVE Db. 208/120. “…for $8,000…” (Satisfied July 31, 1926)

[19] 01/28/1926 -A. J. & Rebecca G. Huvard to Central Bank & Trust [D/T] MURDOCK AVE Db. 208/253. “…for Two Thousand dollars ($2,000)…” (Satisfied July 31, 1926); 04/02/1926 A. J. & Rebecca G. Huvard to Thos. G. Camp [D/T] MURDOCK AVE Db. 232/102.

“…$1,500…” (Satisfied October 22,1926)-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[20] 05/17/1926 A. J. & Rebecca G. Huvard to Central Bank & Trust [D/T] MURDOCK AVE Db. 238/53. “…for Twelve Thousand Five Hundred…$12, 500….) – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[21] These Asheville City Directories can be accessed at the Buncombe County Special Collections at Pack Memorial Library in Asheville, or accessed online at: https://lib.digitalnc.org or https://archive.org

[22] 10/14/1926 (rec’d-10/16/1926) A. J. & Rebecca G. Huvard to W. B. & Anne Kroll Nixon LOT 6 BK 154 P-215 Db. 364/139. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[23] See: 04/01/1926 Lee-Nixon Properties, Inc. PLAT CHARLOTTE HILLSIDE & LENOX STREETS Db. 12/83. Also see the Lee-Nixon Incorporation documents at: 05/25/1926 Lee-Nixon Properties, Inc. [INC.]Db. C009/24.- Buncombe County register of Deeds.

[24] “PLUMBING FIRM ASKS BANKRUPTCY”, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 4, 1927,page 20. -newspapers.com

[25] 05/17/1926 A. J. & Rebecca G. Huvard to Central Bank & Trust [D/T] MURDOCK AVE Db. 238/53. “…for Twelve Thousand Five Hundred…$12, 500…)

[26] 01/13/1927 (rec’d-01/19/1927) W B & Hattie Nixon to John A. Cutchins (of Richmond, VA); F. W. Thomas (Asheville), Trustees [D/T] MURDOCK AVE Db. 253/331. “encumbrance…Mortgage Trust Deed from said Rebecca G. Huvard & A. J. Huvard to Central Bank & Trust Co. to secure indebtedness…Twelve Thousand Five Hundred ($12,500) to New York Life Insurance Co dated May 4, 1926…book 238, at page 53.”. “to secure note drawn by W B Nixon & Hattie S. Nixon…payable to Grace Securities Corporation, Richmond, Virginia…sum of Four Thousand three hundred and eighty and 84/100 dollars ($4,380.84/100)”. “…and it is covenanted and agreed that so long as the debt hereby secured remains unpaid, the said Grantors will keep the improvements on the said real estate constantly insured against fire….”.

[27] Ibid.

[28] 04/27/1927 J. B. Ross, Jr. & Margaret E Ross to Burgin Pennell, TR; W. B. Nixon (party of the third part) [D/T] MURDOCK AVE Db. 259/471. “party of the first part…indebted to party of the third part …for the sum of Four Thousand ($4,000)…”. “being the same land being conveyed to the said Margaret E. Ross, by W. B. Nixon, and wife Hattie Sue Nixon by deed of even date herewith.”

[29] 1930 Federal Census for J. B. Ross at 191 Murdock Avenue, Asheville, NC –https://www.ancestry.com

[30] “Mrs. J. B. Ross, Jr. Will Be Buried At Home”, Asheville Citizen-Times, April 17, 1930, page 16. -newspapers.com

[31] “HUVARD RITES HELD THURSDAY”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 14, 1930, page 8.

[32] “THE ASHEVILLE PLUMBING AND HEATING CO.”, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 2, 1930, page 32. -newspapers.com

[33] 11/28/1930 (rec’-d 01/05/1931) John Mitchell, Succc. Trustee; Central Bank & Trust Co. to Joseph H. Gilmore LOT 6 BK 154 P 215 Db. 433/102. “…Whereas on the 4th day of May 1926, A. J. Huvard and wife, Rebecca G. Huvard, executed to the Central Bank & Trust Company, Trustee for the New York Life Insurance Company, beneficiary… Certain deed of trust…book 238 at page 53…”. “whereas there was default…Central Bank & Trust Company, Trustee did on the 13th day of November 1930 at the Court House door…James C. Dillard became highest bidder.”. “Whereas, James C. Dillard has assigned…Joseph H. Gilmore…”. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[34] 02/06/1934 Joseph H. & Anna M. Gilmore to Mrs. Janet Hoffman LOT 6 BK 154 P 215 Db. 457/570. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[35] 02/14/1944 M. E. & Janet Hoffman to W. C. & Bessie M. Miller MURDOCK AVE Db. 557/156. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[36] “TWO RETAILERS WILL BE DENIED BEER LICENSES”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 3, 1942, page 9. -newspapers.com

[37] Asheville Citizen Times, August 12, 1944, page 6. -newspapers.com

[38] 01/03/1947 W. C. Miller to J. O. Buchanan & William Orr ARTICLES OF CO PARTNERSHIP Db. 629/453. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[39] 02/24/1947 W. C. Miller to Bill C. Miller, Jr. BILL OF SALE Db. 633/161. Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[40] “MAN IS ARRESTED AT RESTAURANT ON WHISKEY CHARGES”, Asheville Citizen- Times, May 4, 1947, page 35. -newspaapers.com

[41] “MAN ACQUITTED ON LIQUOR COUNT IN POLICE COURT”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 17, 1947, page 8. -newspapers.com

[42] 07/21/1947 (rec’d- 11/21/1947) William C. Miller and Bessie Miller DEED OF SEPARATION Db. 649/523. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[43] “HEARING WAIVED IN CASE BY W. C. MILLER IN LOTTERY CASE”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 6, 1947, page 27. -newspapers.com

[44] Asheville Citizen-Times, November 12, 1947, page 13. -newspapers.com

[45] 07/21/1947 (rec’d- 11/21/1947) William C. Miller and Bessie Miller to Bill C. Miller 2 TRS Db. 649/518. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[46] “PADLOCKS PUT ON FOUR PLACES”, Asheville Citizen-Times, August 15, 1948, page 1. -newspapers.om

[47] “Gambling, Lottery Equipment Seized”, Asheville Citizen-Times, September 3, 1948, page 1. -newspapers.com.

[48] 11/23/1949 W. C. & Bessie M. Miller to William J. & Helen Piver MURDOCK AVE Db. 683/493. “…same land…conveyed to Bessie M. Miller from W. B. Nixon…book 668 at page 300…”. [This is true, but it is a misleading recital]

[49] 11/29/1948 W. B. & Anne Kroll Nixon to Bessie M. Miller MURDOCK AVE Db. 668/330. (Quit Claim)-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[50] 12/15/1983 Grace Elizabeth Piver Holden & William Eugene Piver, Co Exs; Helen Piver, EST to Samuel L. Allison & Marsha L. Allison Db. 1340/535. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[51] https://historymyths.wordpress.com/tag/shoes-in-the-wall/