by Dale Wayne Slusser

The river-rock building tradition in Buncombe County was spawned in the early 1920’s at Montreat, NC with the building of the Anderson Auditorium in 1921-22. This river-rock/cobblestone building tradition not only continued in Montreat after the completion of the auditorium, but soon spilled over, first to the nearby town of Black Mountain, and then to Swannanoa and Asheville and other parts of Buncombe County. The story of Montreat’s river-rock tradition is told elsewhere, but in this article, we will take a look at the river rock/cobblestone building tradition as it first spread to Black Mountain and nearby Swannanoa.

What is “river-rock”? River-rock are “water-worn stones” that come from a river, stream or creek. The steepness of the rivers, streams, and creeks and the abundance and volume of water that flow down these waterways from the nearby mountains is such that the rocks or stones that are carried along on the bottoms and sides of the of the waterways are rubbed smooth by the rushing water, much like the gemologist’s rock tumbler which using water and grit and “tumbling”, raw rocks turn into smooth, rounded, polished stones. Here in the mountains of Western North Carolina, river-rock are in abundance, or at least they were in the first half of the twentieth century, during the heyday of building with river-rock. “River-rock” is categorized into three categories, based on its size, pebbles (smallest size), cobbles or cobblestone (small stones), and boulders (large stones). Most of the river-rock used in Western North Carolina tended to be of the smaller stones, known as “cobblestone”.

The river-rock/cobblestone building tradition is an ancient building tradition which goes back ages and originated in Europe and Britain. Cobblestone masonry originally and most often was part of the folk-art vernacular style of architecture. “Folk Art” is defined as: “produced typically in cultural isolation by untrained, often anonymous, artists or by artisans of varying degrees of skill and marked by such attributes as highly decorative design”[1], thereby making it a building tradition that was developed and proliferated mostly by “artisans” (masons and country builders-not architects) and most often limited to small locales.

Unlike the Classical and Georgian styles/traditions of building, which were immediately adopted in the United States in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the cobblestone building tradition of England and Europe did not immediately take hold in America. It was only in the 1830’s-1850s’ that it took hold, and even then it was limited to areas of Upstate New York.[2] However, the main purveyor of the cobblestone building tradition in America, was the resurgence of the cobblestone building tradition by designers and architects of the American Arts & Crafts/Mission-Style Movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Although the resurgence of the use of cobblestone and river-rock during the Arts & Crats period, can be traced first to California architects such as Greene and Greene, the spread of its use was proliferated through home journals, plan books, and magazines, such as Gustav Stickley’s magazine, “The Craftsman”. In a 1908 edition of The Craftsman, Stickley wrote an article titled, “The Effective Use of Cobblestones as A Link Between House and Landscape”, where he promoted the use of cobblestones in building “modern country homes”.[3] Stickley confesses in the article, “We have never specially advocated the use of cobblestones in the building of Craftsman houses, for as a rule we have found that the best effects from a structural point of view can be obtained by using the split stones instead of the smaller round cobbles”.[4] “Nevertheless,” concedes Stickley, “ the popularity of cobblestones and boulders for foundations, pillars, chimneys and even for such interior use as chimney pieces, is unquestioned and in many cases the effect is very interesting”.[5] Ironically, Gustav Stickley states that “the best examples of this natural use of boulders and cobbles” comes from California, although Stickley was writing in Upstate New York close to the epicenter of where the first uses of cobblestones for houses in America were built in the 1830’s-40’s.

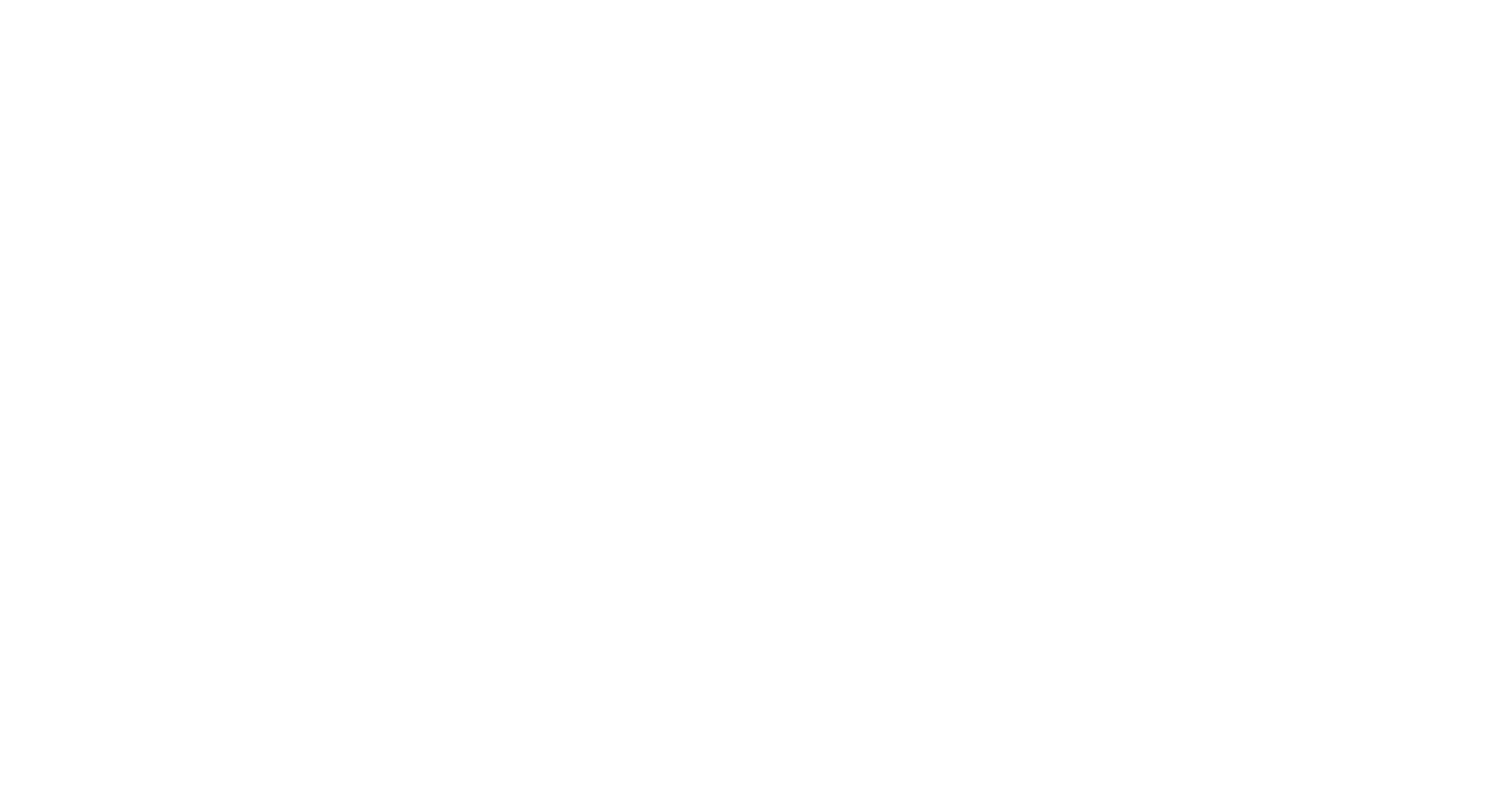

Surprisingly, despite the abundance of river-rock in Western North Carolina, the river-rock/cobblestone building tradition of Western North Carolina did not take hold until the 1920’s with the building of the Anderson Auditorium at Montreat, NC. The first place that the river-rock tradition spread to after the completion of the Anderson Auditorium in 1922, was naturally to nearby Black Mountain, NC. I say naturally because of two primary factors, first of which was that for all residents and visitors to get to Montreat, which was at the end of a long cove, they had to first come through Black Mountain, which was at the head of the cove. The second primary factor was that the workmen who built the auditorium, as well as subsequent river-rock buildings in Montreat, were local men, mostly from Black Mountain and its surrounding area. “Charley Godfrey”, a Black Mountain contractor was hired by Rev. Anderson to be the foreman of the crew of local workmen to build the new auditorium. Although I cannot confirm it, I suspect that Godfrey was also responsible for building the first cottages (in 1923) built in Montreat which utilized river-rock in their construction. While not fully documented that Godfrey built any of the river-rock structures around Black Mountain and Swannanoa, it is highly likely that he did, or at least he trained additional workers to carry out the artistic use of this locally available material.[6] However, Charlie Godfrey was not the only contractor to spread the river-rock building tradition to Black Mountain. Evidence of the origin of the river-rock tradition in Black Mountain and Swannanoa having come from the building of the Anderson Auditorium in Montreat in 1921-22, is seen in the fact that several workmen shown in the 1922 photo (mentioned above), are listed in the 1920 US Census (for Black Mountain) with their occupation as “Laborer” or “Farmer”, yet in the subsequent 1930 US Census they report their occupation as “Carpenter” or “stone-mason” or “rock-mason”. That’s “on-the-job” training at its best! Two prime examples of this are William Herbert “Rip” Cordell and Charlie D. Melton. Although I have not been able to connect them directly to any specific river-rock buildings, both of these men were known to have been active stonemasons in Black Mountain, Montreat, and Swannanoa, during the 1920’s-1940’s (the heyday of river-rock building).

Rip Cordell was born in Riceville (near Asheville, NC) in 1893 to William B. Cordell and his wife, Esther Meredith Cordell. Rip’s father, William B. Cordell, according to the 1900 US Census, was a “stonemason”, and if I’m correct, he was at one time in partnership with his brother Joseph Clemons Cordell, who was also a stonemason, in a company called Cordell Brothers & Company. Cordell Brothers & Company dissolved in 1905[7], and just a year later, in 1906, William B. Cordell passed away. Rip Cordell was 12 years old when his father passed, and therefore probably had not learned the stonemasonry trade from his father, at least he appears to have not been trained in the trade. And in fact, when he was 23 years old, he drafted into the army in 1917, where he listed his occupation as “Laborer”.[8] And as late as the 1940 census, Rip Cordell listed his occupation as “Carpenter”, though by 1950, he was listed as a “rock mason, carpenter”. Until his death in 1986, Rip Cordell was a well-known stonemason in Black Mountain and Swannanoa.

Charlie D. Melton, also shown in the 1922 photo, was a man that no doubt learned the art of stonemasonry while helping to build the Anderson Auditorium at Montreat. Charles Dolph Melton was born in 1884 to James Rollins Melton and his wife Margaret. In 1907, Charlie married Callie Mease Melton of Haywood County. In the 1910 US Census, Charlie’s occupation was listed as “Woodsman, Chopper”, no doubt working in the Timbering industry. Then in the 1920 Census, just prior to the start of the building of the Anderson Auditorium, his occupation is listed as “Laborer, Working Out”. Yet, in the 1930 Census, Melton’s occupation was listed as “Stonemason”, and in 1940 as “Carpenter, Building Contractor, and then in the 1950 US Census he listed his occupation as “rock-mason”. When Charlie Melton died in 1972, he was reported to have been a retired “brick mason”.

I have however been able to connect several of the builders and tradesman who had constructed the Montreat auditorium, and shown in the 1922 photo, to river-rock structures (mostly houses) in Black Mountain. Let’s take a look at some of these builders and the river-rock buildings that they can be connected to.

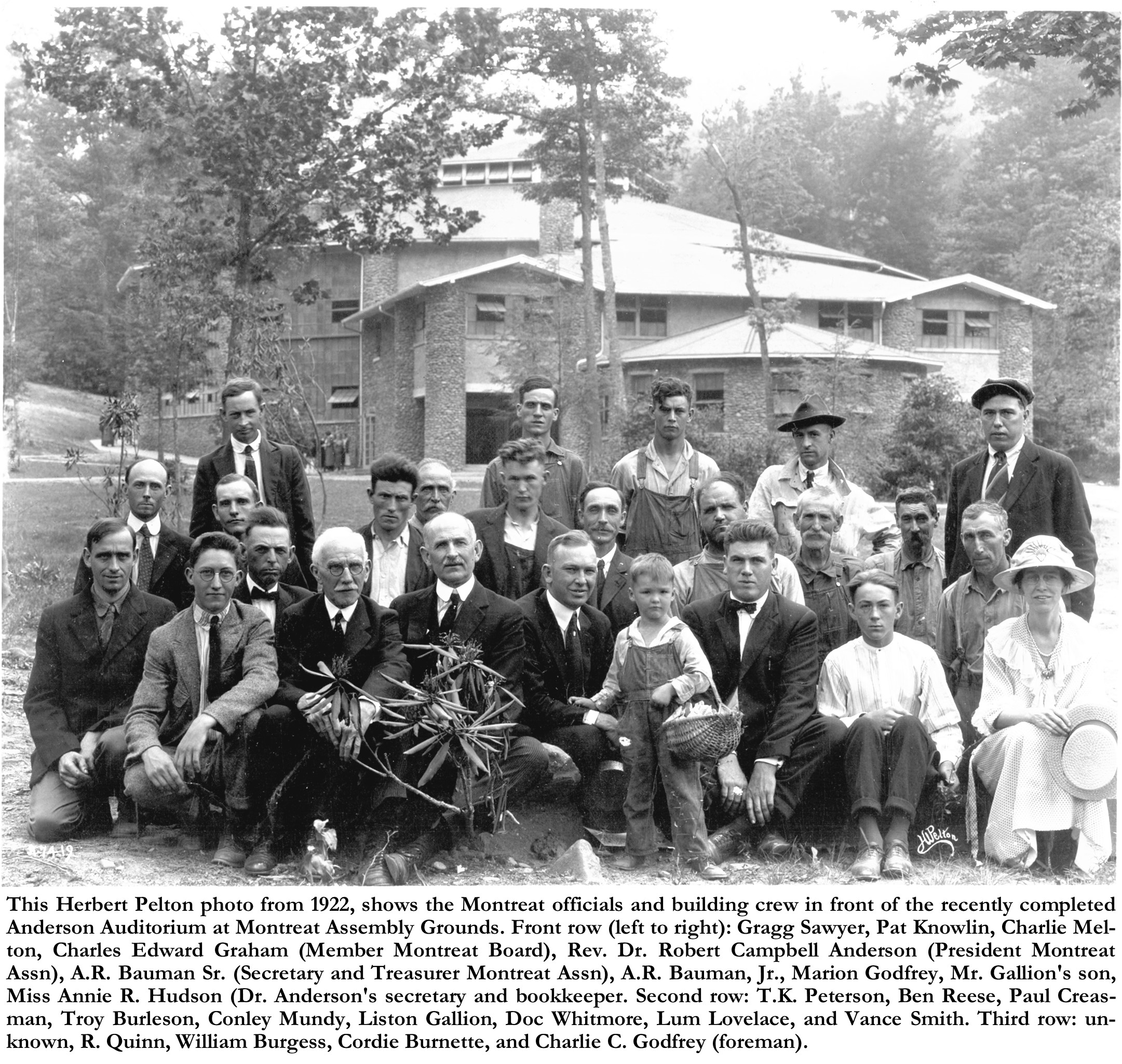

One of the men in the 1922 photograph was listed as “T. K. Peterson”, who I believe was actually “J. K. Peterson”. Jessie K. Peterson was listed in the 1920 U. S. Census as a resident of Black Mountain, NC with the occupation of “Carpenter-House”.[9] Peterson can be connected to one of the first all river-rock houses built in Black Mountain, at what is now 103 Midland Avenue. In 1925, Jessie Peterson and his wife Nora, purchased “Lot 12” on Midland Avenue, just a few blocks from downtown Black Mountain.[10] The Petersons also purchased, along with “Lot 12”, lots 7, 8, and 10 in the same block, all from carpenter, E. E. Weast. Weast probably built and lived in the house on “Lot 10”, as it is the only one that shows on the 1924 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for Black Mountain. A few weeks later, the Peterson’s sold Lot 12 to Rev. Marcus W. Dargan, a Methodist Minister from Old Fort, NC.[11] But oddly, the Dargans sold the property back to the Petersons in February 1926, less than a year later. Then in March of 1926, the local newspaper announced that “Mr. & Mrs. J. K. Peterson have moved into their new home near McGraw’s Coffee Shop.”[12] “McGraw’s Coffee Shop” was near the beginning of Midland Avenue at 201 E State St, Black Mountain. However, the Petersons may have been moving into the house on Lot 10 OR 12! Oddly, they sold the property at Lot 12, a few months later, in March of 1926 to David C. Russ and his wife Lillian.[13] Even more bizarrely, just a few months later, Russ sold the property back to his brother-in-law, Marcus W. Dargan (Mrs. Dargan and Mrs. Russ were sisters),[14] which was just a year after Dargan had purchased the property the first time! Suffice it to say that it is difficult to ascertain who built the house at 103 Midland Avenue, whether it was Peterson or Dargan. My suspicion is that Peterson may have built the house for Dargan in 1925, and then in 1926 when Rev. Dargan was transferred to a pastorate in Belmont, NC, he sold the house back to Peterson, and then perhaps David Russ purchased the house to save it for his brother-in-law, Rev. Dargan who then bought the house back as his retirement home. Despite who may have built it, the small one-story, 2-bedroom bungalow, totally clad in river-rock, is a typical example of the use of river-rock in Black Mountain during the 1920’s, shortly after the first use of river-rock in Montreat. J. K. Peterson had been one of the workmen who built the Andersen Auditorium in nearby Montreat in 1921-22. As the auditorium was built almost entirely of river-rock and steel, it’s likely that carpenter Peterson learned stonemasonry while working on the auditorium.

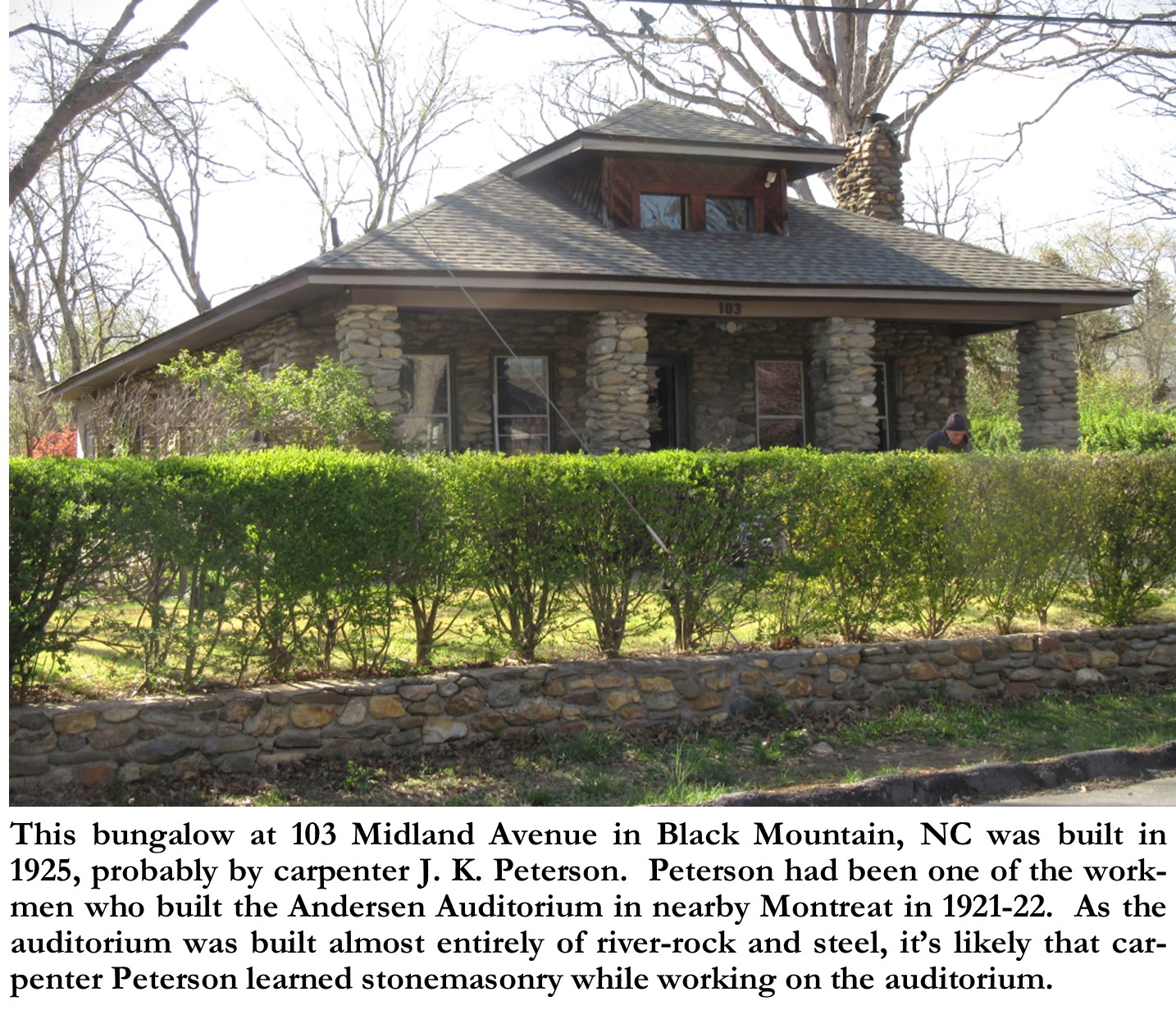

Interestingly, one of the first examples of a river-rock house built in Black Mountain is the house built at 901 Montreat Road, for newlyweds David C. Russ and his bride Lillian Wall Russ in 1923. Yes, this is the same D. C. Russ who later in 1926 purchased the house mentioned above at 103 Midland Avenue. The two houses are not only connected in their ownership, but also, they both may have been built by J. K. Peterson. A month after purchasing the lot for this house, at the corner of Montreat Road and Cotton Avenue, D. C. Russ, borrowed $1,080 against the property from his brother-in-law Marcus Dargan.[15] In that transaction, a “J. K. Patterson” acted as the trustee for Dargan. Could this have been “J. K. Peterson” the builder? Another interesting aspect of this house that may point to J. K. Peterson as the builder is its resemblance in size and configuration to the house built at 103 Midland Avenue. Both houses were built as a one-story hipped roof bungalow with a front porch under the main roof, topped with a single hipped-roof dormer. And of course, both houses are built of river-rock. However, the house at 901 Montreat Road, which was probably built in 1923, just a year after the completion of the Anderson Auditorium at Montreat, is more refined and features two distinctive characteristics from the auditorium construction, the use of cobblestone (small river-rock) and the use of round river-rock columns (for its front porch posts). Both houses also feature low front river-rock terrace walls.

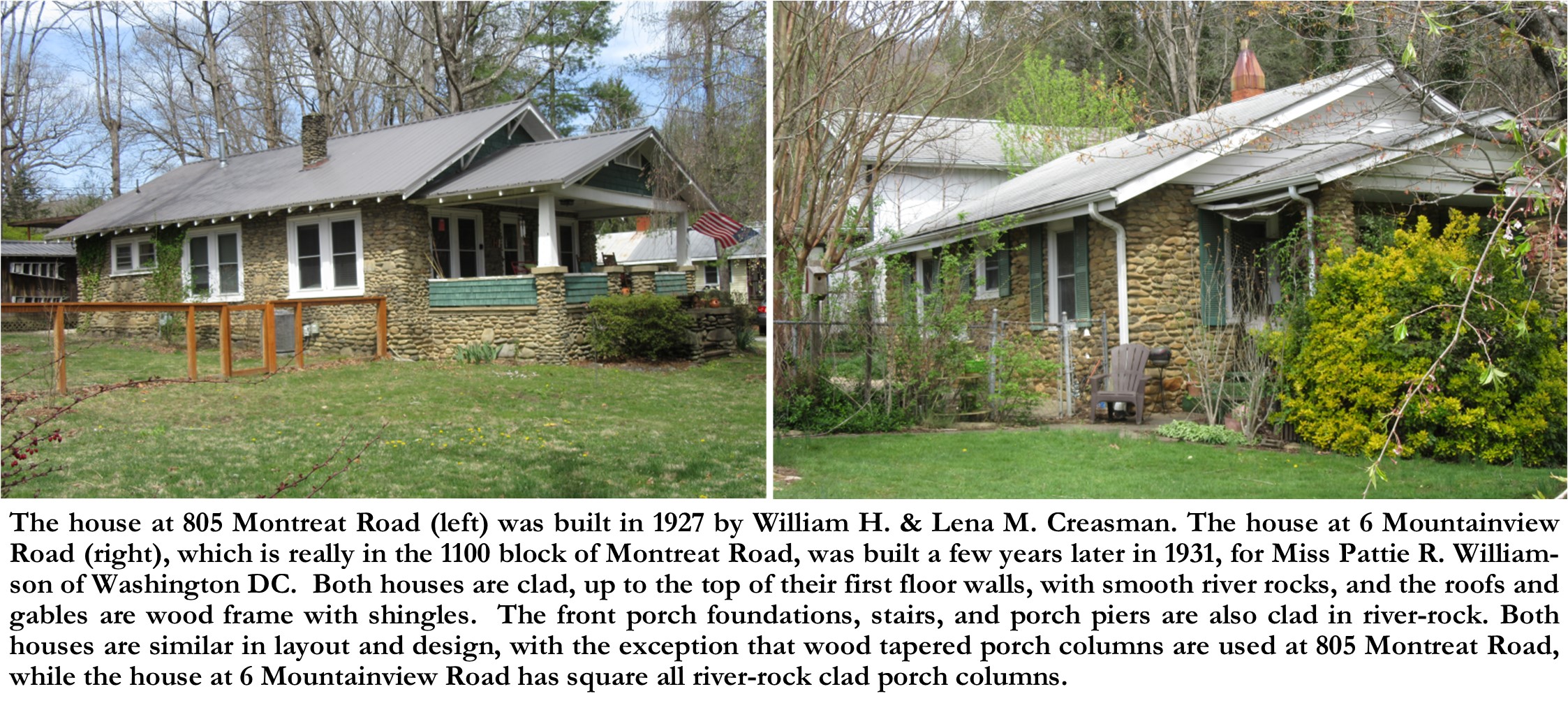

Although we know little of the connections of the builders and stonemasons to the known river-rock houses (who built which ones), the fact remains that there are an abundance of all-river-rock houses and commercial buildings in Black Mountain, that were built from the 1920’s-1940’s. Two further examples, were also built along Montreat Road, one at 805 Montreat Road and one at 6 Mountainview Avenue (it fronts on Montreat Road). The house at 805 Montreat Road was built in 1927 by William H. & Lena M. Creasman. Will Creasman, was a local barber. The house that the Creasmans built is a typical front-gabled bungalow with a gabled-roof front porch. The house is clad up to the top of the first-floor walls, with smooth river rocks, and the roof and gables are wood frame with shingles. The front porch foundation, stairs, and piers are also clad in river-rock, with tapered wood columns at each pier to hold up the porch roof. The house at 6 Mountainview Road, which is really in the 1100 block of Montreat Road, not far from the Creasman house, was built a few years later in 1931, for Miss Pattie R. Williamson of Washington DC. The house is at the corner of Montreat Road and Mountain View Avenue, which was the entrance to a 1926 development, called “Sunrise Terrace”, which was built around the former Clinton L. Stepp house/estate. The Williamson house is very similar to the layout and design of the Creasman house, with the exception that instead of wood tapered porch columns, it has square river-rock porch columns.

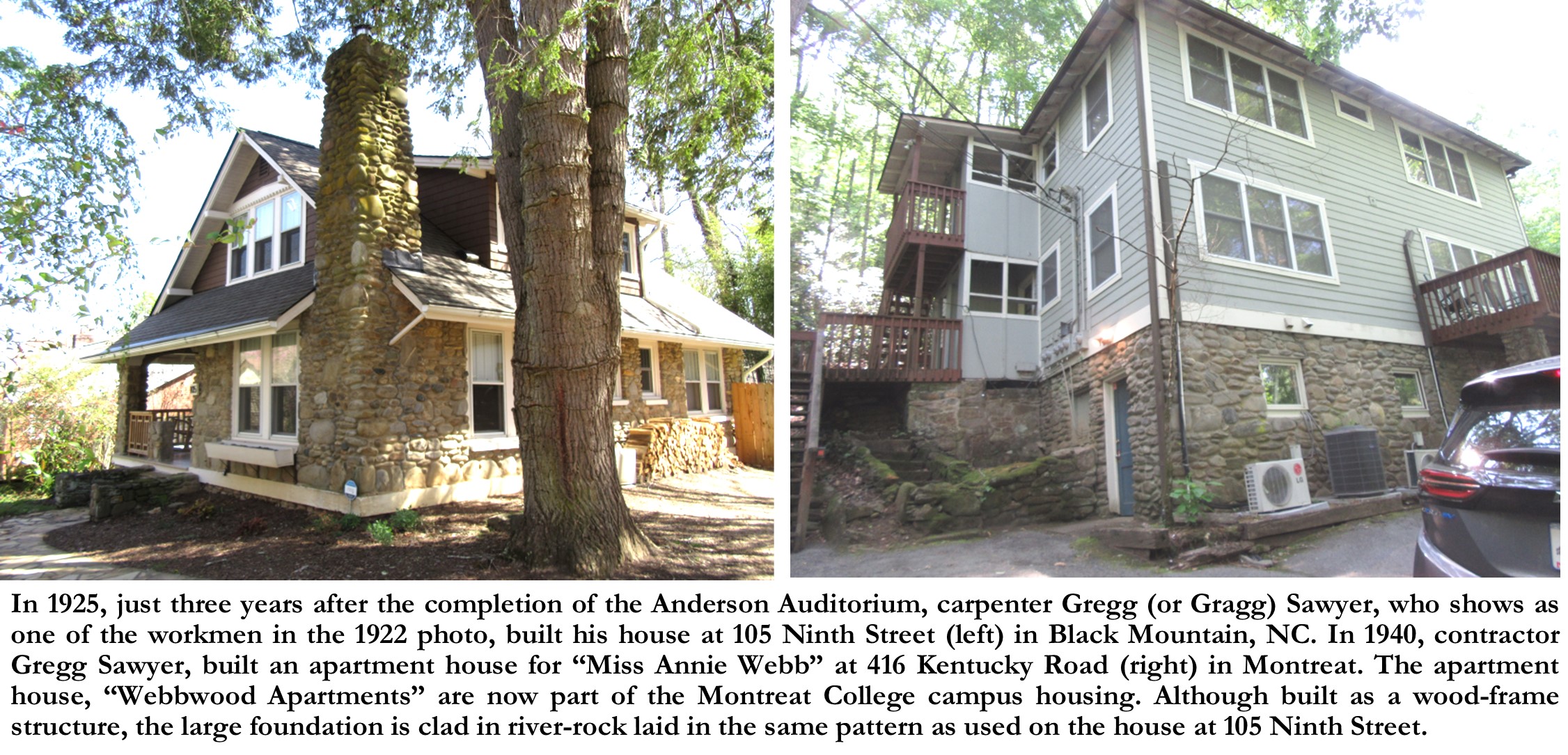

In 1925, just three years after the completion of the Anderson Auditorium, carpenter Gregg (or Gragg) Sawyer, who shows as one of the workmen in the 1922 photo, built his house at 105 Ninth Street, which is just off of Montreat Road. The property had previously been the site of a house built for J. A. Head, which just after being purchased in 1920 by W. A. Burnette (first Warden of the Asheville Watershed at the North Fork), had burned to the ground. H. D. Melton and his wife Maud, purchased the property from Burnette in 1922[16], after the fire, and in 1925, sold a divided-out lot to Sawyer[17]. Gregg Sawyer built a 1-1/2 story front gabled bungalow on his lot (addressed as 105 Ninth Street). The design and detailing, such as the recessed asymmetrical front porch, balanced on the house’s other front corner by a massive chimney, all centered on the prominent steeply pitched bracketed front gable, has the hallmarks of having been designed by an architect, or at least having being drawn up (perhaps by Sawyer?) prior to construction. The distinctive characteristic of the finely designed house is its river-rock stone cladding on the first-floor walls and chimney. Instead of using only cobblestone river-rock, Sawyer chose to integrate larger river-rocks (small boulders) laid vertically with their large smooth flat top surfaces showing. This pattern of river-rock stonemasonry would soon become more popular than just using only cobblestones, as not only did it give a more interesting pattern to the stonework, but perhaps more importantly it used less stone and was easier to lay than the small cobblestones. The house remained the Sawyer family home for decades, and Gregg Sawyer was a prominent builder in Black Mountain and Montreat until his death in 1971. In 1940, contractor Gregg Sawyer, built an apartment house for “Miss Annie Webb” at 416 Kentucky Road (right) in Montreat.[18] The apartment house, “Webbwood Apartments”, are now part of the Montreat College campus housing. Although built as a wood-frame structure, the large foundation was clad in river-rock laid in the same pattern as used on the house at 105 Ninth Street.

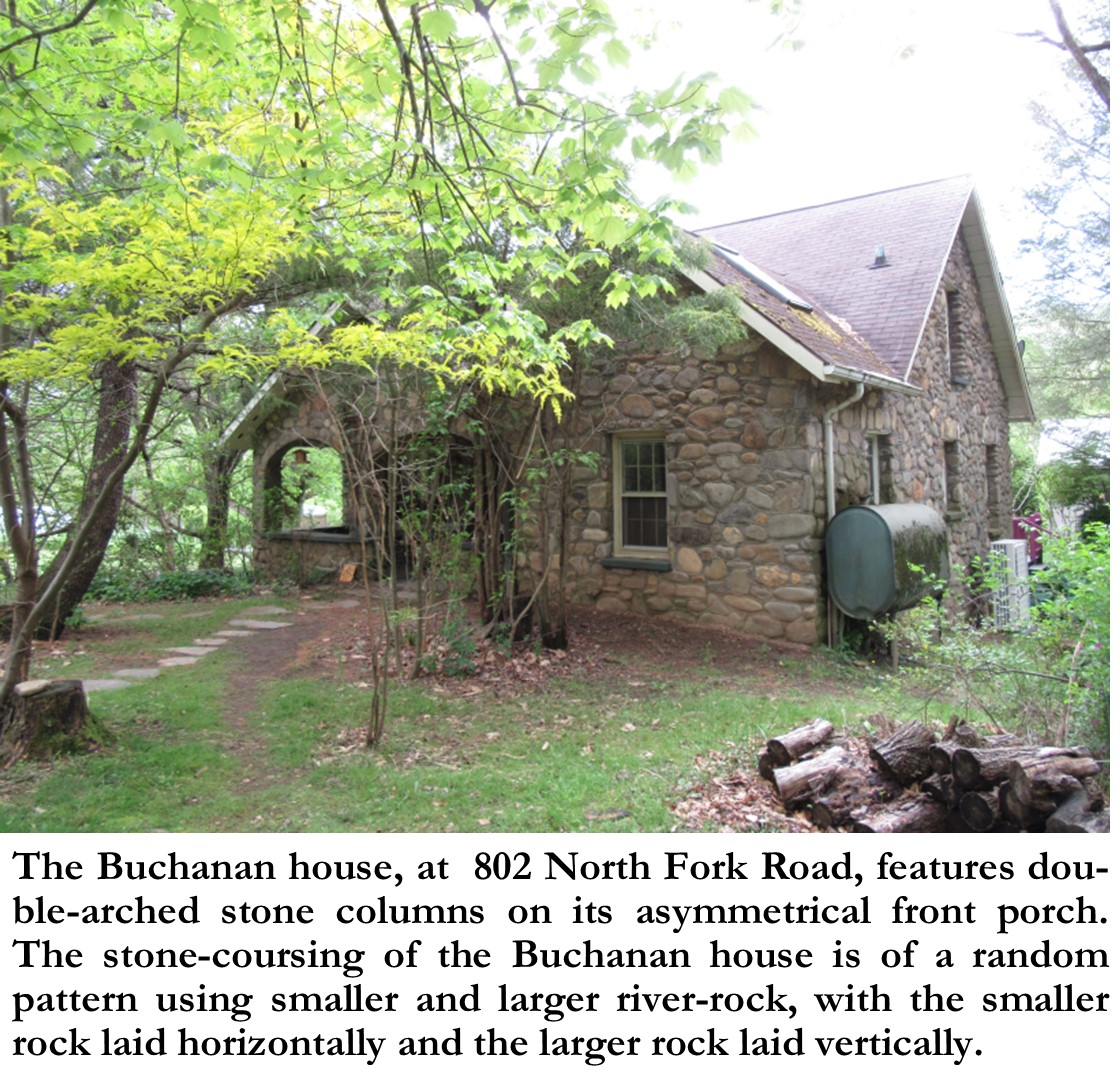

By the 1930’s and 1940’s, though not yet completely extinct, the river-rock building tradition in Black Mountain and Swannanoa had dwindled and mostly gone out of style. However, two known examples of all-river-rock houses built in Black Mountain during this period, interestingly, are both known to have been built by their owners (mostly self-built) using local river-rock from the same source, the North Fork of the Swannanoa River. In 1936, Ben Buchanan and his wife Hattie purchased two tracts of land, west of Black Mountain, between the North Fork Road and the North Fork of the Swannanoa River, from the estate of E. W. Grove. Grove had purchased the land in the early 1920’s for part of his Grove Stone quarry company, and in fact the Buchanans purchased the property with an active lease to the quarry. It seems natural and logical that Ben Buchanan used river-rock, probably literally from his backyard, out of the North Fork of the Swannanoa River, to clad his new home. The Buchanan house features double-arched stone columns on its asymmetrical front porch, which is balanced on its right side by a projecting front gable-roofed “wing” (only projecting a few feet). The stone-coursing of the Buchanan house is of a random pattern using smaller and larger river-rock, with the smaller rock laid horizontally and the larger rock laid vertically. The result gives the house a unique and pleasing textural and sculptural quality to its appearance.

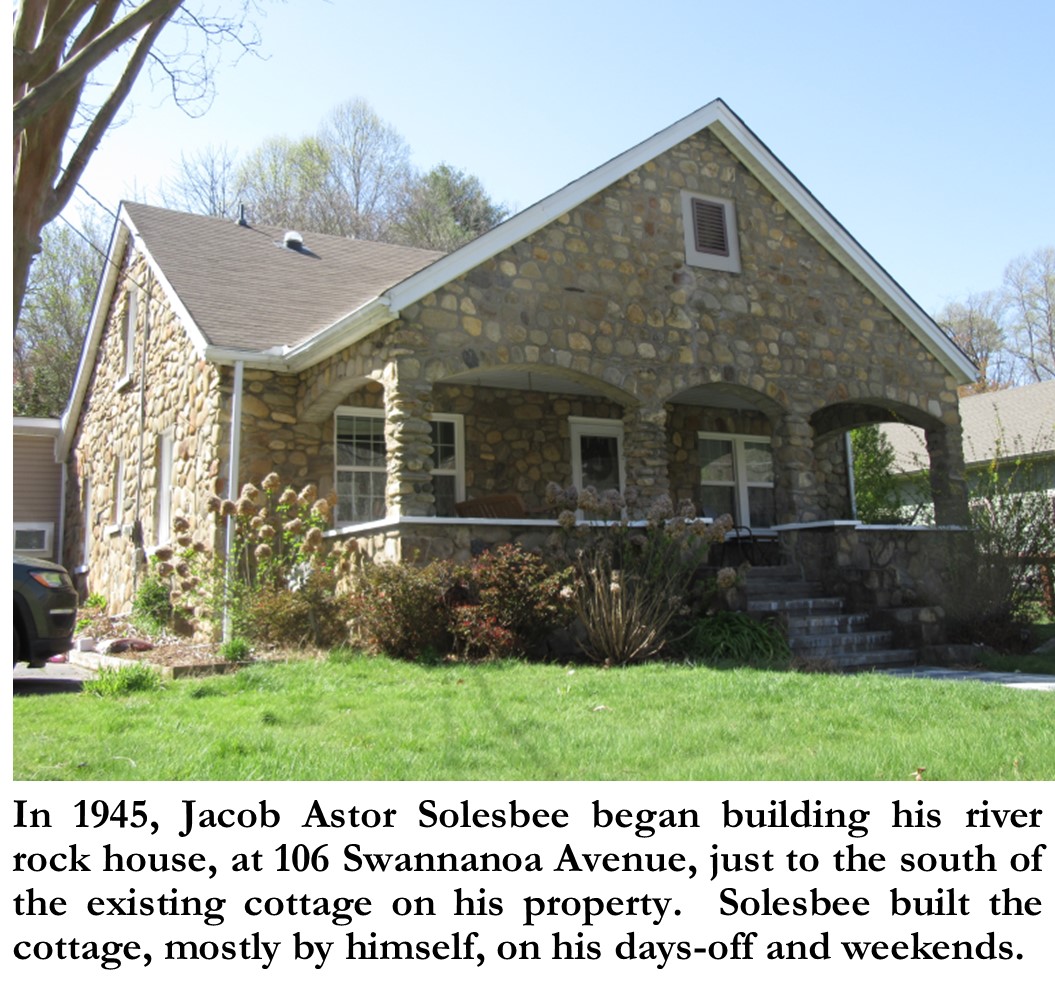

In 1945, Jacob Astor Solesbee purchased several contiguous lots along Swannanoa Avenue, in the former Methodist Colony at Lake Tomahawk in Black Mountain.[19] On the lots was a wood frame house, probably built as a summer cottage in 1914, by Edgar J. Nottingham, Jr. and his wife Mary Payne Nottingham.[20] The Solesbee family moved into the Nottingham cottage when they purchased the property. According to family recollections, shortly after moving into the Nottingham cottage, Jacob Astor Solesbee began building his river rock house, just to the south of the existing cottage. Solesbee built the cottage, mostly by himself, on his days-off and weekends. The river rock came from the nearby Grovestone Sand & Gravel Company property. However, the company did not deal in river-rock, but they would allow Solesbee to bring his pickup truck onto their property to gather the river-rock from the North Fork of the Swannanoa, which flowed through their property. Therefore, Solesbee did not have to pay for the stone! [21] Solesbee chose to build his house as a one-story front-gabled bungalow. A distinctive feature of the house is the triple arched front porch, which like the rest of the house, is clad in river-rock.

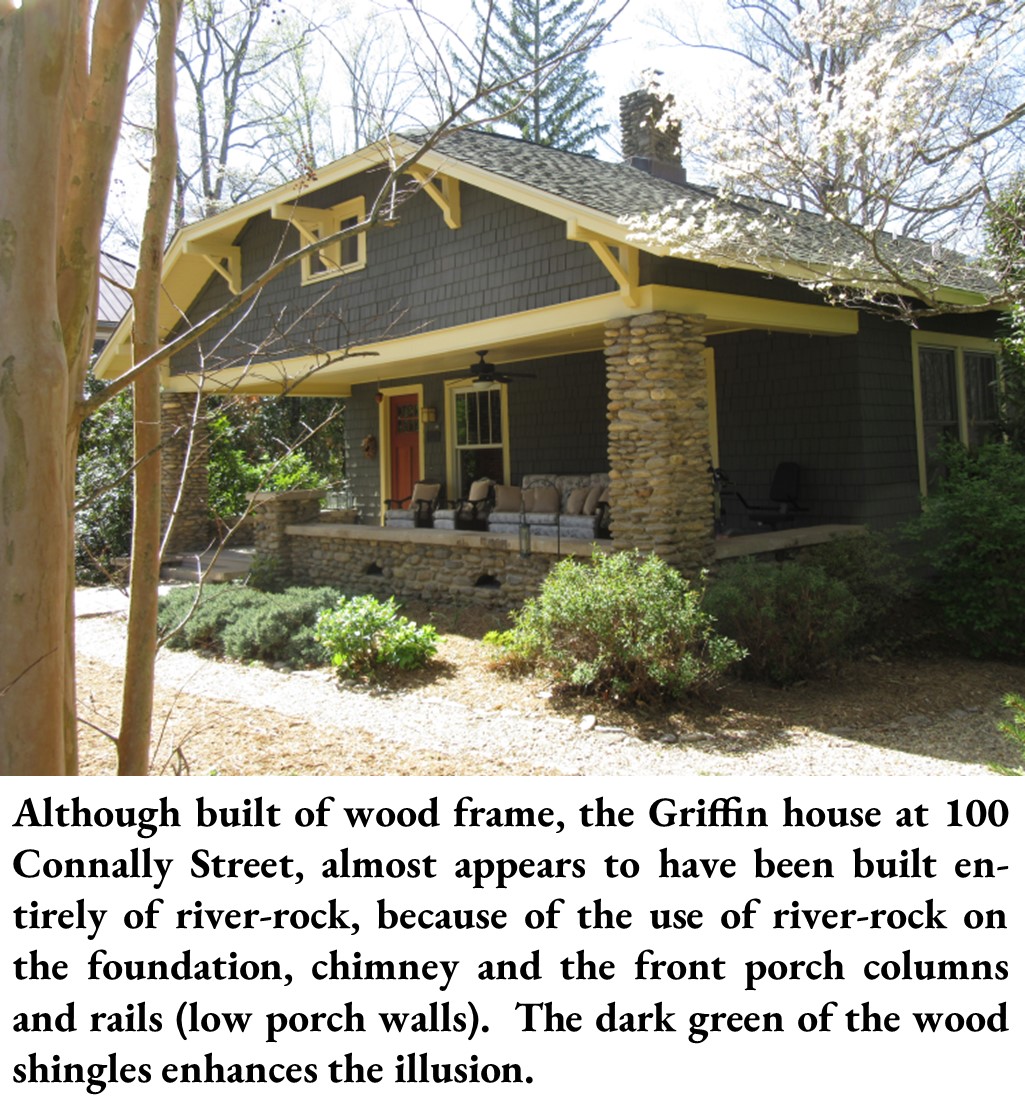

Although there are several “all-river rock” houses in Black Mountain, there are even more houses that are not completely clad in river-rock, yet they use river-rock as a distinctive feature, mainly on their foundations, chimneys, front porches, and/or retaining walls. Here are just a few examples. In 1917, Goldsboro, NC businessman, W. H. Griffin, built a summer cottage on the north side of Connally Street, in the former Methodist Colony, on the western side of Black Mountain.[22] In 1925, Griffin began building a new summer home, adjacent to, and east of, the existing cottage. Griffin chose to build his new home as a one-story frame Arts & Crafts bungalow, with a front facing truncated (clipped) gabled roof, which covered the entire house, including the recessed front porch. Although built of wood frame, the Griffin house almost appears to have been built entirely of river-rock, because Griffin used river-rock on the foundation, chimney and the front porch columns and rails (low porch walls). The wood-shingled gable and house walls are now painted dark green, providing a backdrop that highlights the prominent use of river-rock on its front porch especially. After completing their new summer bungalow, the Griffins, subdivided off their existing cottage, and sold it to Martha Munger.

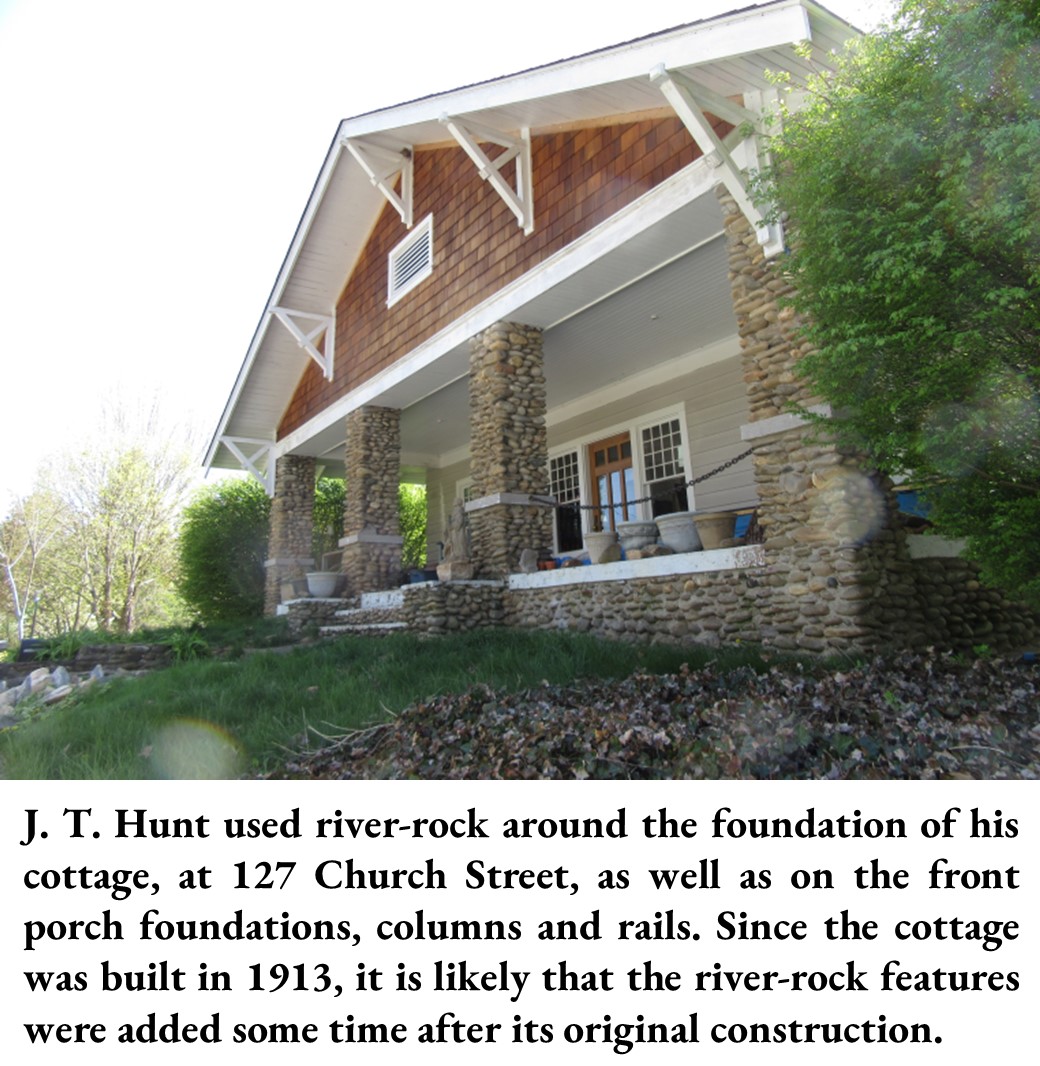

Another example of the use of river rock as a distinctive feature is the cottage/bungalow built at 127 Church Street, just around the corner from the Griffin house. This cottage was built in 1913 by and for Greensboro, NC building contractor, John Townsend Hunt. Hunt had first visited the mountains in 1910, seeking rest to heal from a “nervous breakdown”.[23] In 1913, on another visit to the mountains, J. T. Hunt purchased the lot on Church Street and began construction of a new family summer home, which was named “Craggy View”. The Hunt family would spend almost every summer at their summer home from 1913 until they sold it in 1931.[24]. J. T. Hunt died two years later.[25] Hunt used river-rock around the foundation of his cottage, as well as on the front porch foundations, columns and rails. Of course, the question is, was the river-rock part of the original 1913 construction? If so, then it predates the use of river-rock at Montreat by almost a decade. A thorough architectural study/inspection may give us the answer; however, I suspect that the river-rock was a later addition to the cottage. Since the Hunts owned the cottage until 1931, it is plausible that though the river-rock was not original, it still could have been added by them, perhaps in the mid-1920’s.

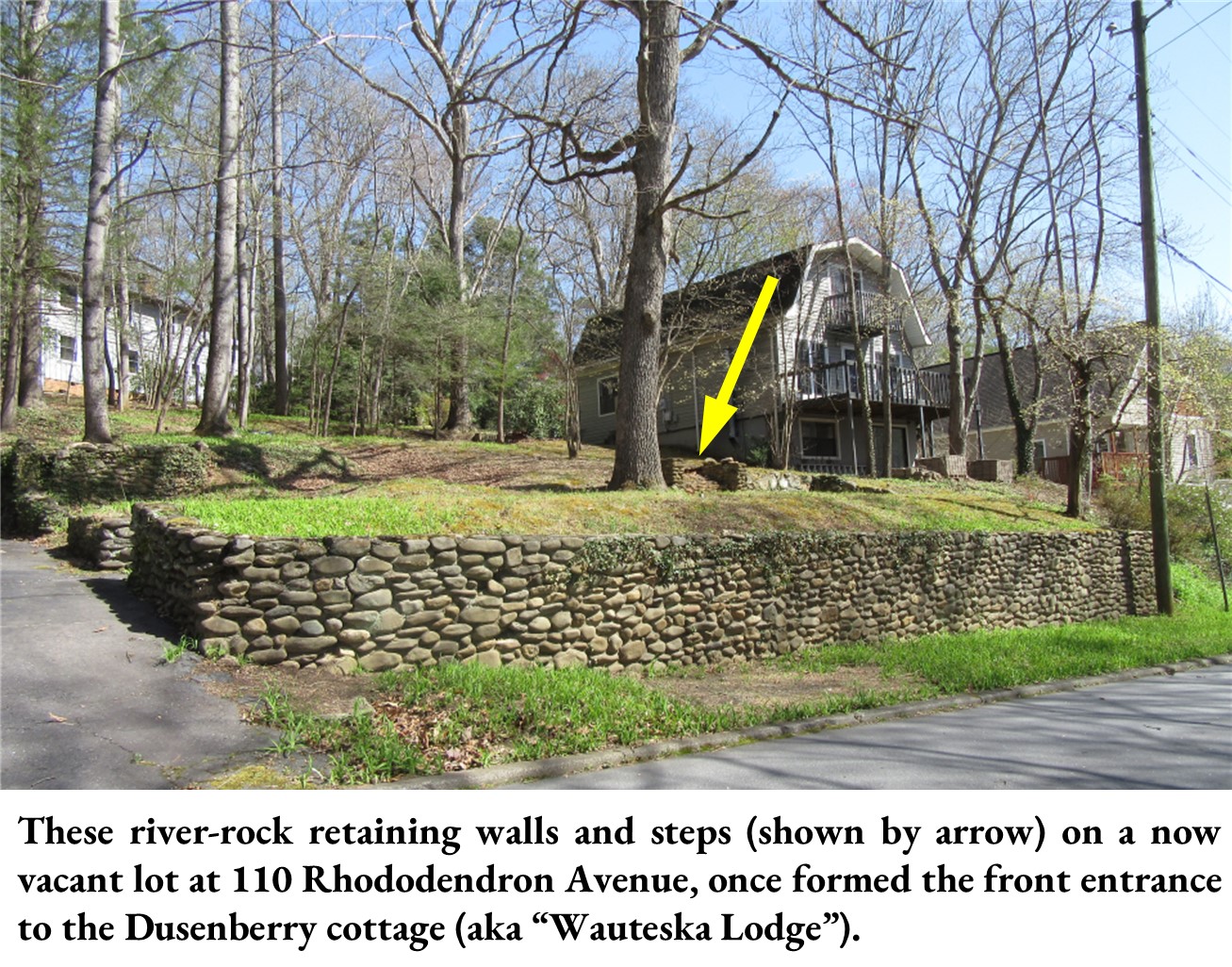

By far, the most profuse use of river-rock in Black Mountain was/is on retaining walls and front steps, and other parts of the landscape. As there are so many examples, I cannot give you a comprehensive list of all the examples of this use of river-rock in Black Mountain, but instead, I will point you to just a few examples. One of my favorite examples is on a series of old retaining walls and steps on a now vacant lot at 110 Rhododendron Avenue, in the former Methodist Colony at Lake Tomahawk. The lot was the site of “Wauteska Lodge”, built in 1915 as a summer cottage for Daniel & Sarah Dusenberry, of Lake Como, Florida.[26] The cottage, which is no longer standing was built at the top of the hillside lot, but accessed from the bottom of the site, off of Rhododendron Avenue, thereby necessitating the need for low retaining walls to create a terraced front lawn. If the river-rock walls and steps are original to 1915, then again, they would predate the building of the Montreat auditorium. D. E. Dusenberry owned the house until his death (he died in the house) in 1923, and then the cottage was inherited by his maiden sister-in-law Mary E. “Libbie” Haight, who unfortunately lost the cottage to foreclosure in the mid-1930’s.[27] Since the rocks are larger than a “cobble”, I suspect that the river-rock walls and front steps were not original, but added perhaps in the 1940’s.

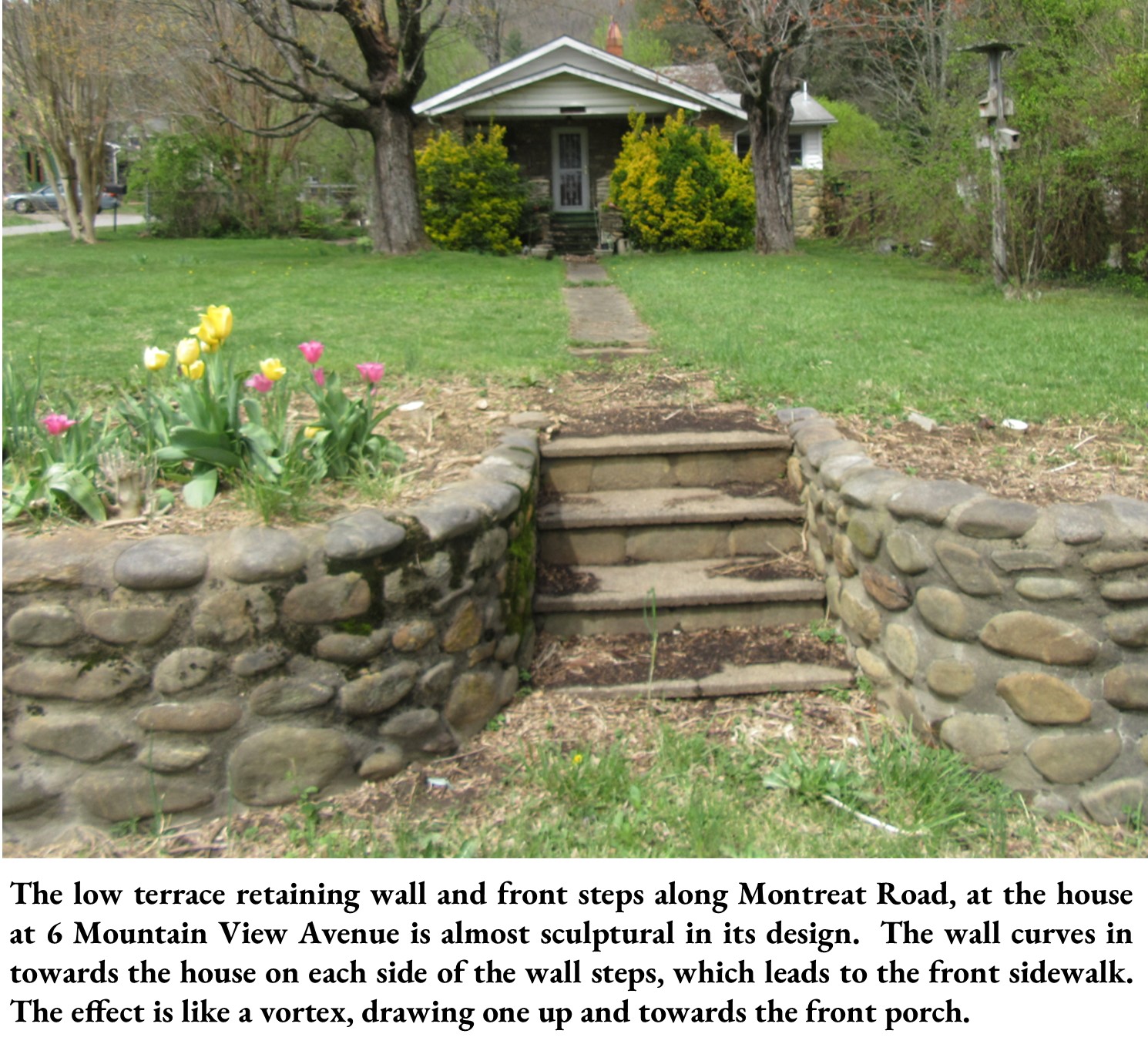

Most of the all-river-rock houses in Black Mountain also have low terraced walls at the front. One of the most attractive is the low terrace retaining wall and front steps along Montreat Road, at the house at 6 Mountain View Avenue (mentioned earlier). Almost sculptural in its design, the wall curves in towards the house on each side of the wall steps, which leads to the front sidewalk. The effect is like a vortex, drawing one up and towards the front porch.

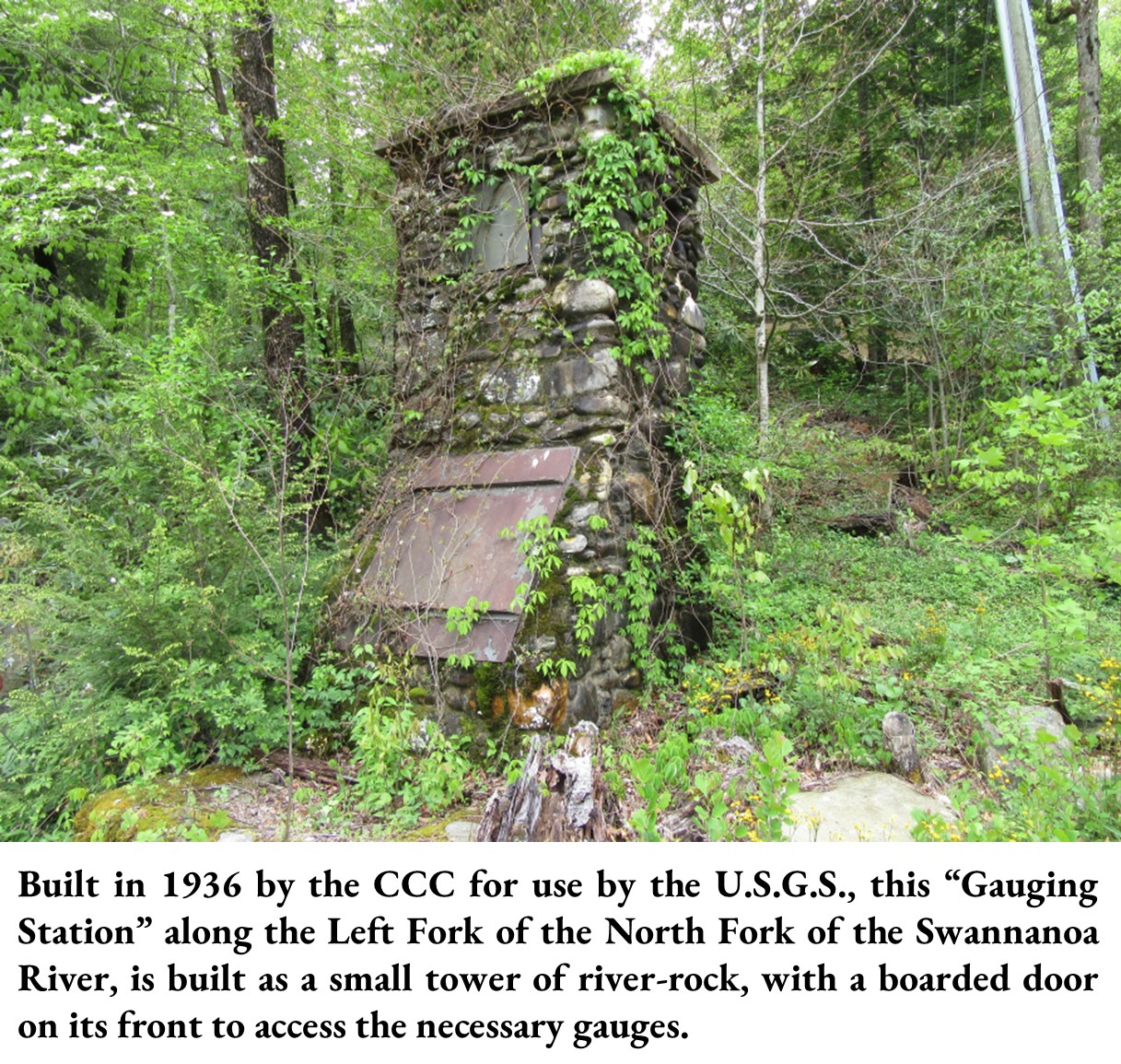

One final example of the use of river-rock for a landscape feature, in Black Mountain is the unique “Water Gauge House” along the Left Fork of the North Fork of the Swannanoa River on the western side of town. This feature, which looks less like a “house” and more like a monument, houses a “gauging station”. This “gauging station” is a hydrological station that provides information about the flow of the North Fork Swannanoa River. “The station, built in 1936 by the C. C. C.[28] for use by the U.S.G.S.,”[29] was built as a small tower of river-rock, with a boarded door on its front to access the gauges.

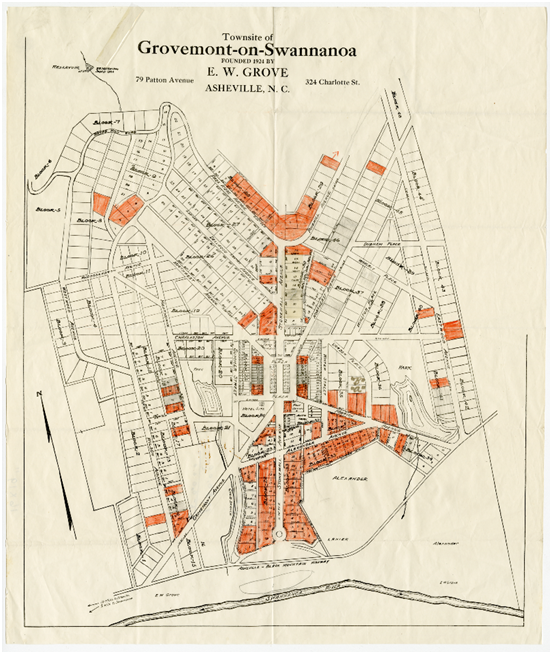

As the river-rock building tradition began to spread into Black Mountain from Montreat, after the building of the Anderson Auditorium in 1922, it also began to spread westward towards Asheville, with its first stop in nearby Swannanoa, NC. In June of 1924, just as he was finishing his massive project of removing the old Battery Park Hotel and accompanying hill, Asheville developer, Edwin Wiley Grove, announced plans for the building of a new “town”, to be vainly called “Grovemont -on- Swannanoa”. Grove’s new town was planned to be built 12 miles east of Asheville (just west of Black Mountain) along the Swannanoa River at the bend in the river at the North Fork of the river. Grove decided to design his new town to take advantage of its beautiful “natural” setting, touting that the town was to be built on the site of what the “older mountain residents”, told him was originally called by the early settlers, “The Garden of Eden”, for its natural beauty, “…where majestic mountains are covered with magnificent hardwood forests, and silvery streams dash down their slopes forming crystal lakes in all directions…”.[30]

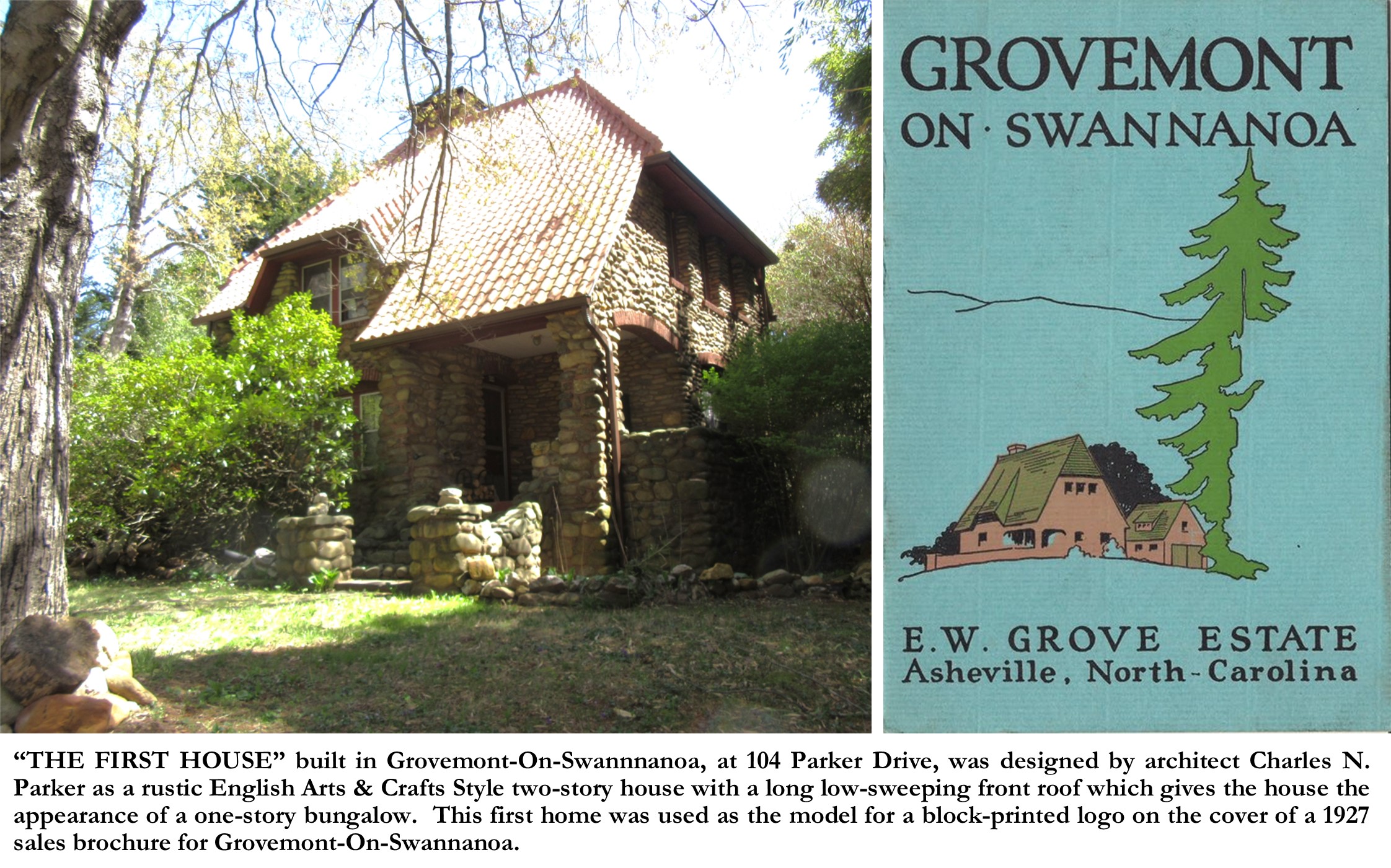

To entice homebuyers, Grove built several model homes at the start of the development of Grovemont. In November of 1924, the Commerce Union & Trust Company, which Grove had recently formed to handle his real estate business, advertised in the local newspaper: “FIRST HOUSE IN GROVEMONT, BUILT BY E. W. GROVE, FOR SALE BY US”.[31] Using a litany of superlatives, the advertisement also boldly proclaimed: “A beautiful stone house built to last a thousand years and then some. Built by Mr. Grove’s own workmen, by his own plans and according to his ideas. The workmen, the plans and the ideas are all good.”[32] This first house to be built in Grovemont, built of river-rock, was the house, ironically built at 104 Parker Drive. I say ironically, because despite “Mr. Grove’s” bravado, the design of both Grovemont-On-Swannanoa, and the house at 104 Parker Drive, were the work of brothers Harry L. Parker and Charles N. Parker! The brothers had moved to Asheville from Ohio in the early 1900’s. H. L. Parker, was a civil engineer who, while working for Grove, designed the layout and master plan for the Grovemont development. Charles N. Parker was an independent architect with his own practice and was responsible for the design of the house at 104 Parker Drive. And in fact, in a subsequent advertisement, three months later, in February 1925, titled “THE STONE HOUSES AT GROVEMONT”, it was further announced that, “THERE ARE three of them, unique architectural designs of Charles N. Parker and typifying the very best workmanship to be found in the strictly modern home.”[33] Of course, not to be outshone, the next sentence in the advertisement claims: “They are in truth GROVE-CRAFT Homes, calculated to please the most fastidious purchaser.”[34] Also, with a further slight concession, the article announced that “Mr. Grove planned and designed this wonderful civic community with the assistance of H. L. Parker, Civil Engineer and City Planner.”[35]

The “FIRST HOUSE”, also called “STONE HOUSE No. 1”, built on “Lot No. 1 Block 22”[36], now addressed as 104 Parker Drive, was completely clad in river-rock. Charles Parker designed the house as a rustic English Arts & Crafts Style two-story house with a long low-sweeping front roof which gives the house the appearance of a one-story bungalow. Interestingly, the river-rock walls, and brick windowsills and lintels, along with its red clay-tile roof, display the same rusticity and ruggedness of E. W. Grove’s 1913 Grove Park Inn. River-rock was also used on the first story of the accompanying double-car garage and servants’ quarters, built next to the residence. This first home was used as the model for a block-printed logo on the cover of a 1927 sales brochure for Grovemont-On-Swannanoa.

What the advertisements failed to say was that these three “stone houses” at Grovemont were built not of quarried rock, but using “river-rock”, gathered from the river and creek beds of the Swannanoa River and its tributaries. Playing into the town’s themed narrative of its “natural beauty”, and using the principles of the Arts & Crafts movement, of using natural building materials, locally sourced, it’s not surprising that Grove (or the Parker brothers) chose to use river-rock as a distinctive building material in his new development. Of course, it was more than likely also an economical choice of materials, as in conjunction with the building of Grovement, in 1924, E. W. Grove established Grovestone Gravel & Sand Company, just east of the new town, along the banks of the North Fork of the Swannanoa River. Grove reported that “Grovestone” was to be “a great rock and gravel crushing plant to provide material for his construction activities in the Swannanoa Valley”.[37] The site of Grovestone was (and still is) on the alluvial plain straddling the North Fork of the Swannanoa River. An “alluvial plain” is defined as “a level or gently sloping flat or a slightly undulating land surface resulting from extensive deposition of alluvial materials by running water.”[38] The headwaters of the Swannanoa River, like Flat Creek (on the other side of the mountain at Montreat), are up on Mt. Mitchell, the highest peak east of the Mississippi River. Thus, much of the “alluvial material” that was available to Grove at Grovestone was “river-rock”, deposited along the Swannanoa River.

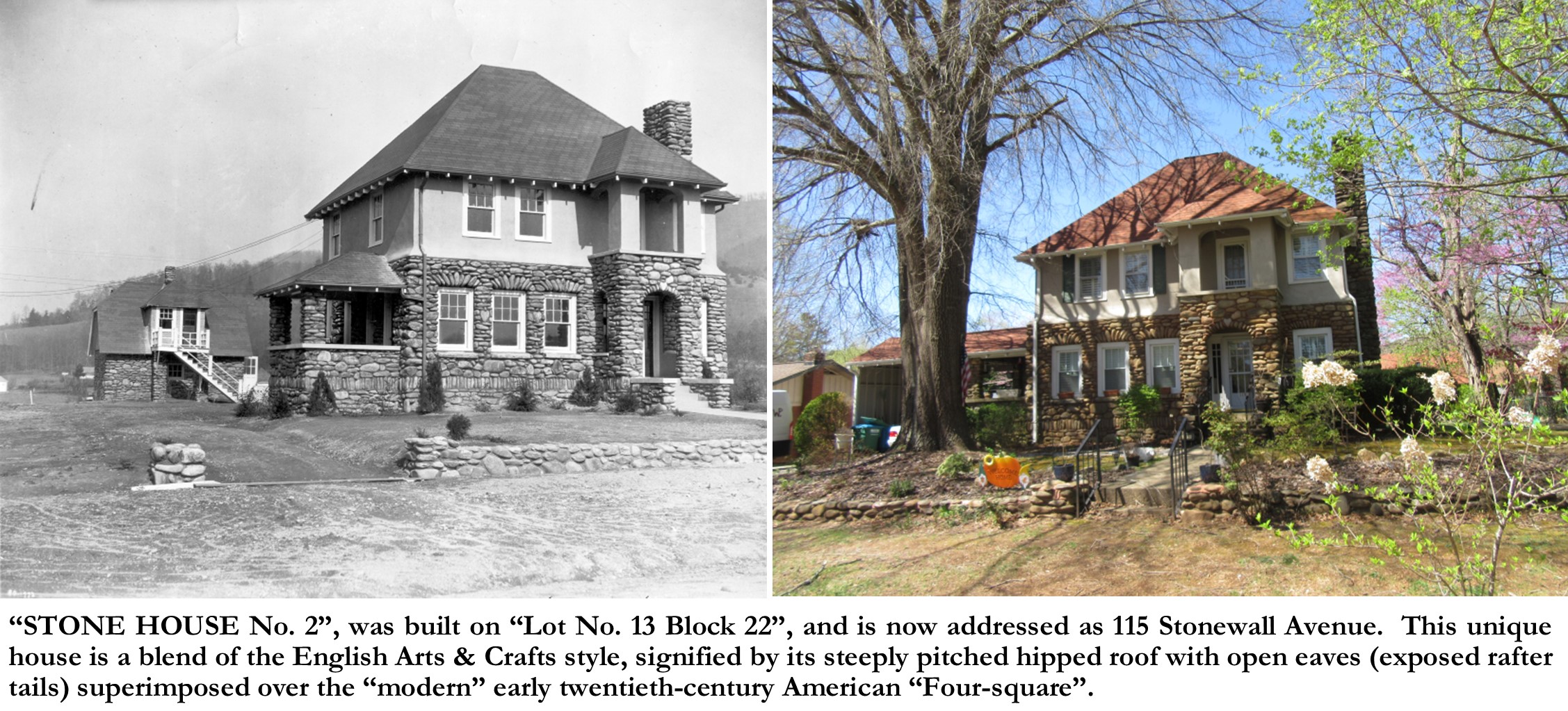

The other two of the three “first houses” of Grovemont, not only both featured river-rock on their exterior, but they were built adjacent to each other, just around the corner from the first house, on Stonewall Avenue. “STONE HOUSE No. 2”, was built on “Lot No. 13 Block 22”[39], and is now addressed as 115 Stonewall Avenue. This unique house is a blend of the English Arts & Crafts style, signified by its steeply pitched hipped roof with open eaves (exposed rafter tails) superimposed over the “modern” early twentieth-century American “Four-square”. In their helpful book, A Field Guide to American House Styles, Virginia and Lee McAlester, explain that in American domestic architecture, “Ground plan and elevation combine to make several persistent and recurring patterns or families of shapes that are characteristic of most American houses”.[40] The “Four-Square”, is characterized as being two-story, four rooms on each floor, giving each façade, as well as the overall shape of the house, the shape of a “square”, topped by a pyramidal hipped roof. The “Four-Square”, although having its origins in the “Prairie-Style”, popularized by Frank Lloyd Wright, was often combined with other various “styles”, such as the Arts & Crafts and Colonial Revival Styles. The house at 115 Stonewall Avenue is clad in river-rock on its first story, and stucco on its second story. A feature of this house is the two-story front entrance porch, with its river-rock clad, arched first floor entrance portico. The decorative use of river-rock is also displayed on this house, on the large side chimney, at the front entrance arch, at the flat arches above the first-floor windows, and on the use of upright stones to form a belt course between the foundation and the first floor of the house. The original side porch, with its river-rock columns and rails, has at some point been extended as a porte-co-chere over the driveway.

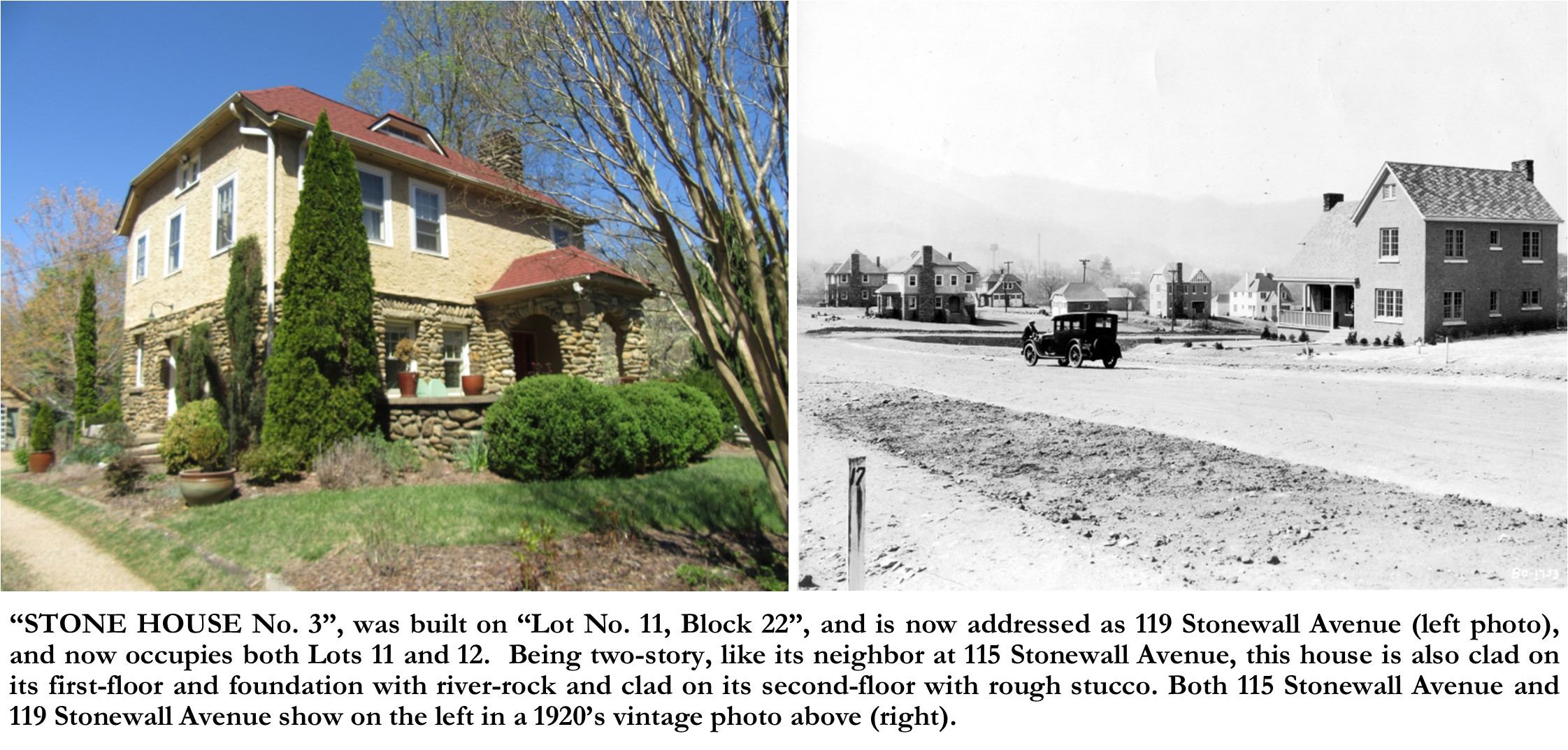

“STONE HOUSE No. 3”, was built on “Lot No. 11, Block 22”,[41] and is now addressed as 119 Stonewall Avenue, and now occupies both Lots 11 and 12. Being two-story, like its neighbor at 115 Stonewall Avenue, this house is also clad on its first-floor and foundation with river-rock and clad on its second-floor with rough stucco. This house is even less categorically identifiable of any major “style”, although its side-gabled roof with its truncated (clipped) gables, and its use of local natural building materials, are reminiscent of the Arts & Crafts Style. The house has a one-story arched front entrance portico, as well as a small front terrace both of which are clad in river-rock. An odd but interesting detail of this house is the use of river-rocks on the flat arches above the windows on the first floor. They are like those on the house at 115 Stonewall Avenue, EXCEPT that they are placed above flat solid stone lintels at each window. River-rock is also used on the house’s large side chimney.

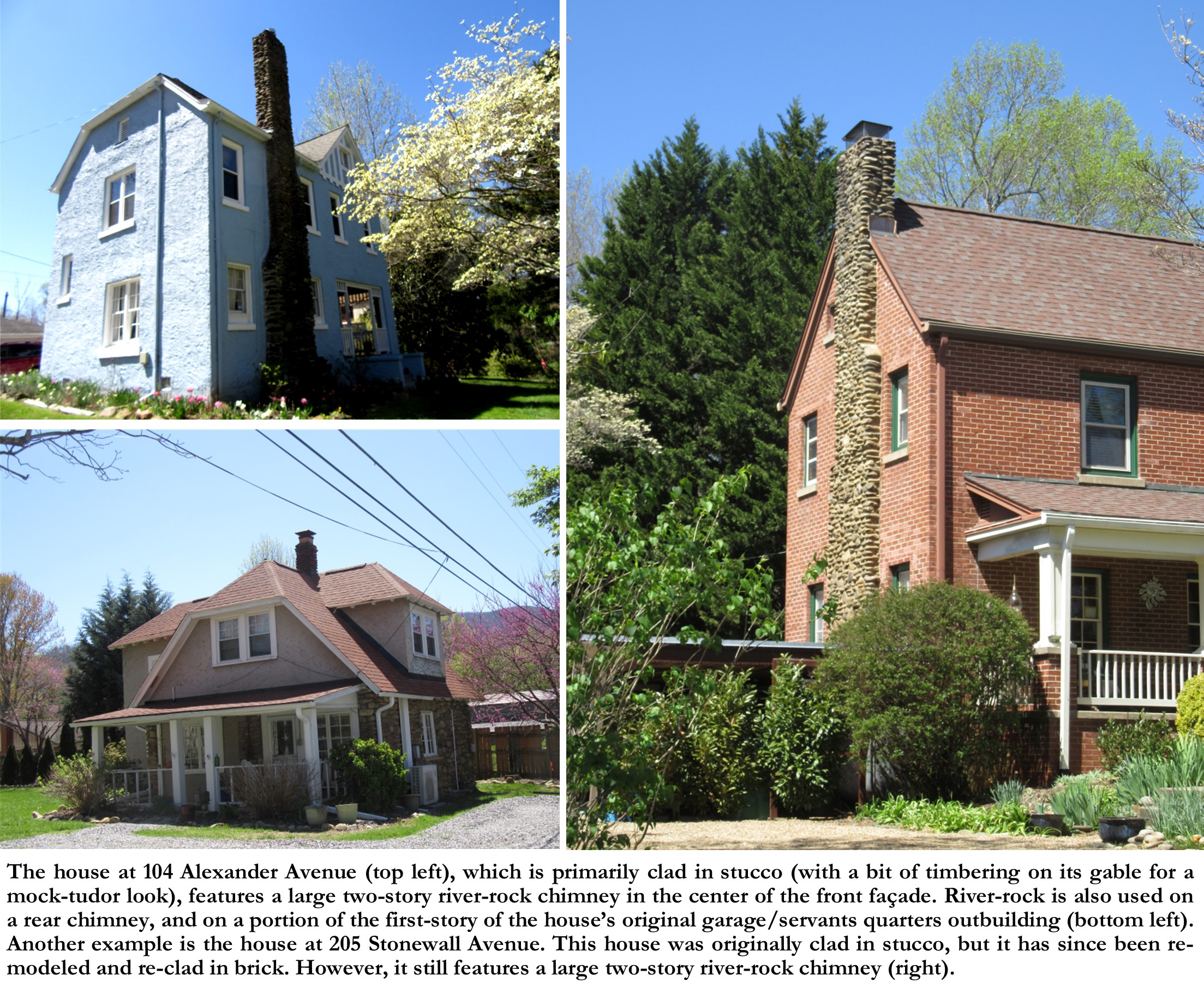

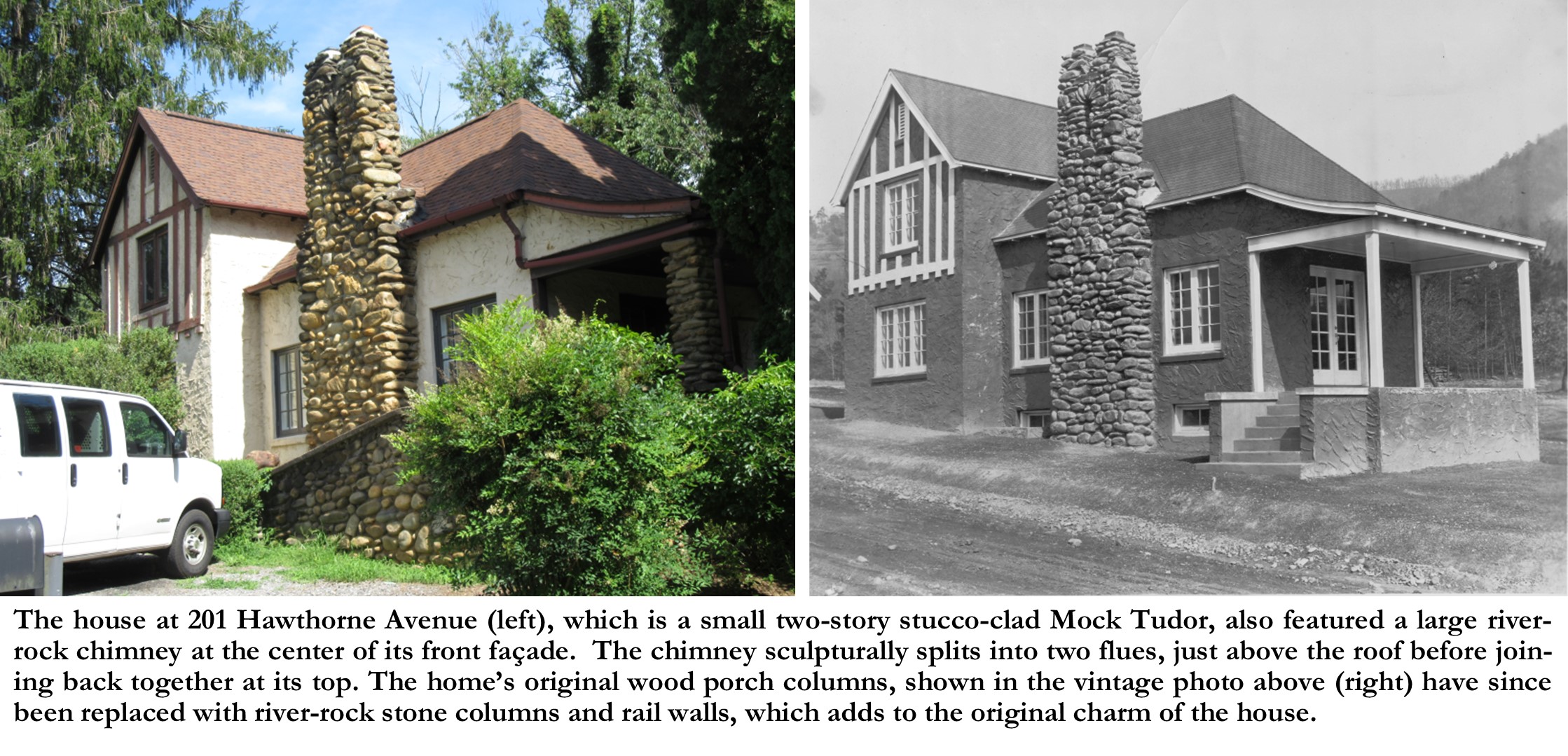

Other houses were constructed in Grovemont, using river-rock only as an accent feature. The house at 104 Alexander Avenue, which is primarily clad in stucco (with a bit of timbering on its gable for a mock-tudor look), features a large two-story river-rock chimney in the center of the front façade. River-rock is also used on a rear chimney, and on a portion of the first story of the house’s original garage/servants’ quarters outbuilding. Another example is the house at 205 Stonewall Avenue. This house was originally clad in stucco, but it has since been remodeled and re-clad in brick. However, it still features a large two-story river-rock chimney. The house at 201 Hawthorne Avenue, which is a small two-story stucco-clad Mock Tudor, also featured a large river-rock chimney at the center of its front façade. The chimney sculpturally splits into two flues, just above the roof before joining back together at its top. The home’s original wood porch columns have since been replaced with river-rock stone columns and rail walls, which adds to the original charm of the house.

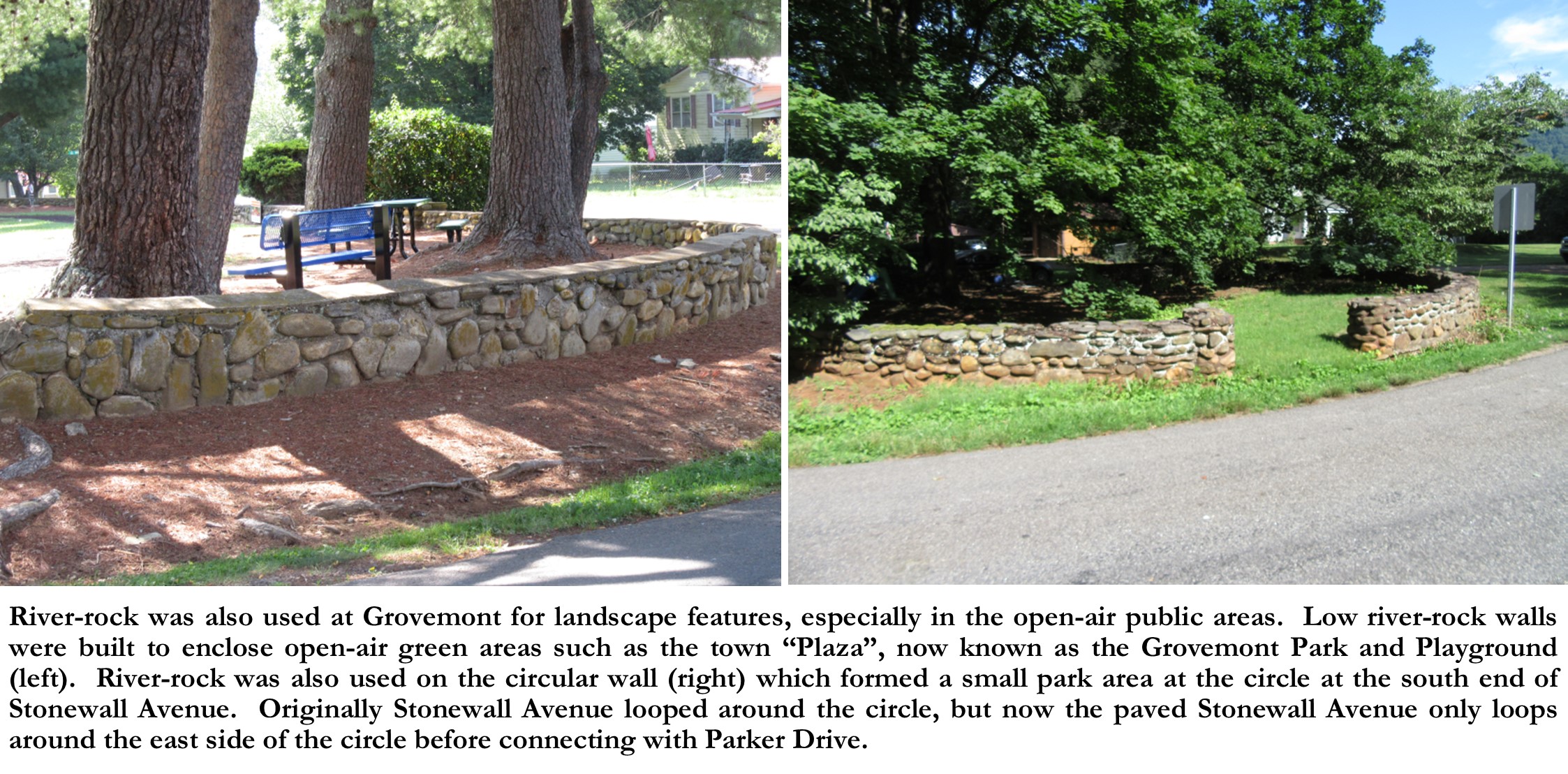

River-rock was also used at Grovemont for landscape features, especially in the open-air public areas. Low river-rock walls were built to enclose open-air green areas such as the town “Plaza”, now known as the Grovemont Park and Playground. This wall was original and remains to this day. River-rock was also used on the circular wall which formed a small park area at the circle at the south end of Stonewall Avenue. Originally Stonewall Avenue looped around the circle, but now the paved Stonewall Avenue only loops around the east side of the circle before connecting with Parker Drive.

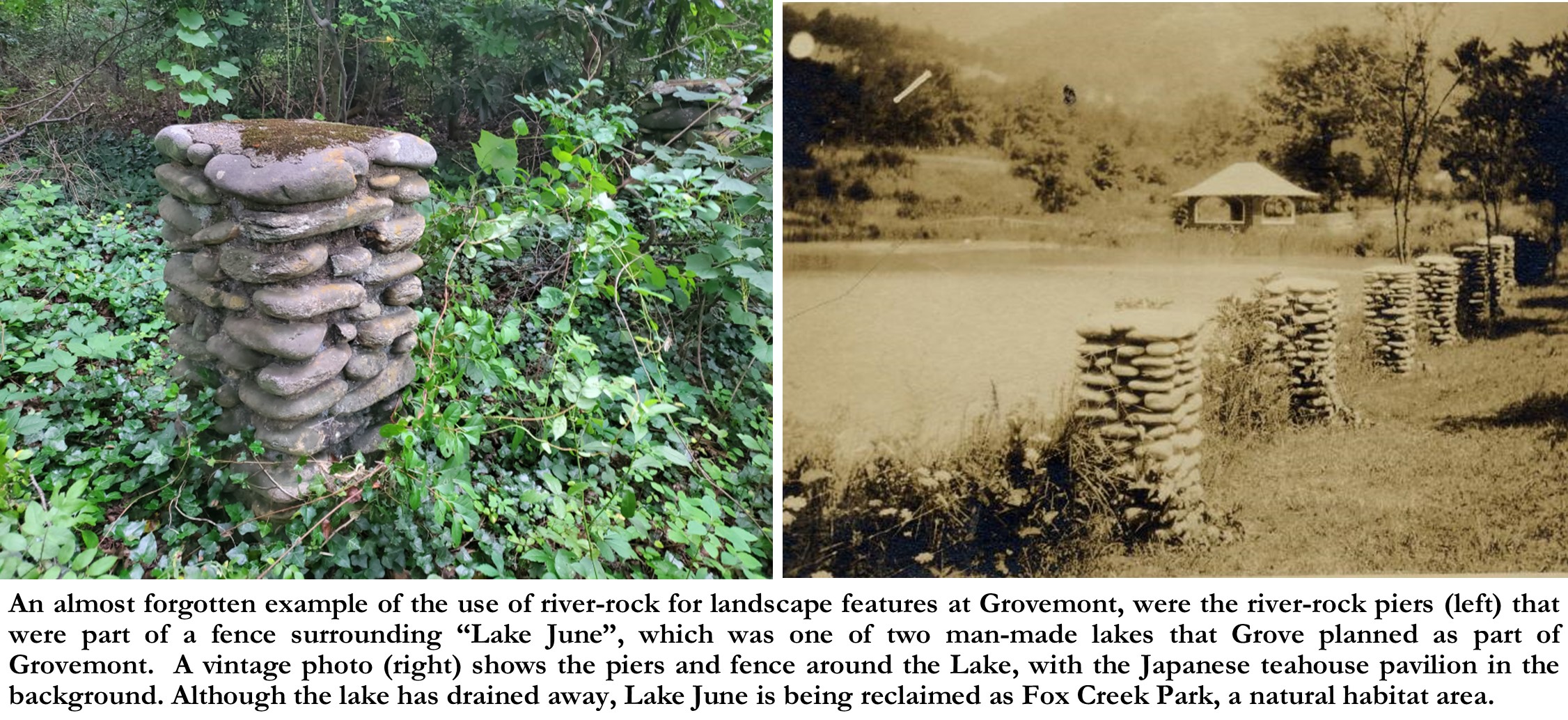

An almost forgotten example of the use of river-rock for landscape features at Grovemont, were the river-rock piers that were part of a fence surrounding “Lake June”, which was one of two man-made lakes that Grove planned as part of Grovemont. “Lake June” was on the western side of the town, near Hawthorne Avenue at Ivanhoe Drive. A vintage photo shows the piers and fence around the Lake, with the Japanese teahouse pavilion in the background. The lake was surrounded by a “beautifully simple Japanese garden”.[42] Both the Japanese garden and design principles as well as the use of river-rock, were proponents popularized in the early twentieth century by the American Arts & Crafts Movement, specifically beginning in California, by architects such as the Greene & Greene brothers, whose work was characterized by smooth Japanese wood joinery and the use of natural materials in both buildings and landscapes. Although “Lake June” has been drained for many years, it and its surrounding parkland has recently been acquired by the Swannanoa Community Council, through the advocacy of local resident, Allen Dye, and it is now being developed as Fox Creek Park,[43] to include a walking path, wildlife habitat and educational resource on the former site of Lake June in Grovemont. A few of the river-rock piers, which once surrounded the lake, remain and have recently been uncovered from their invasive kudzu overgrowth.

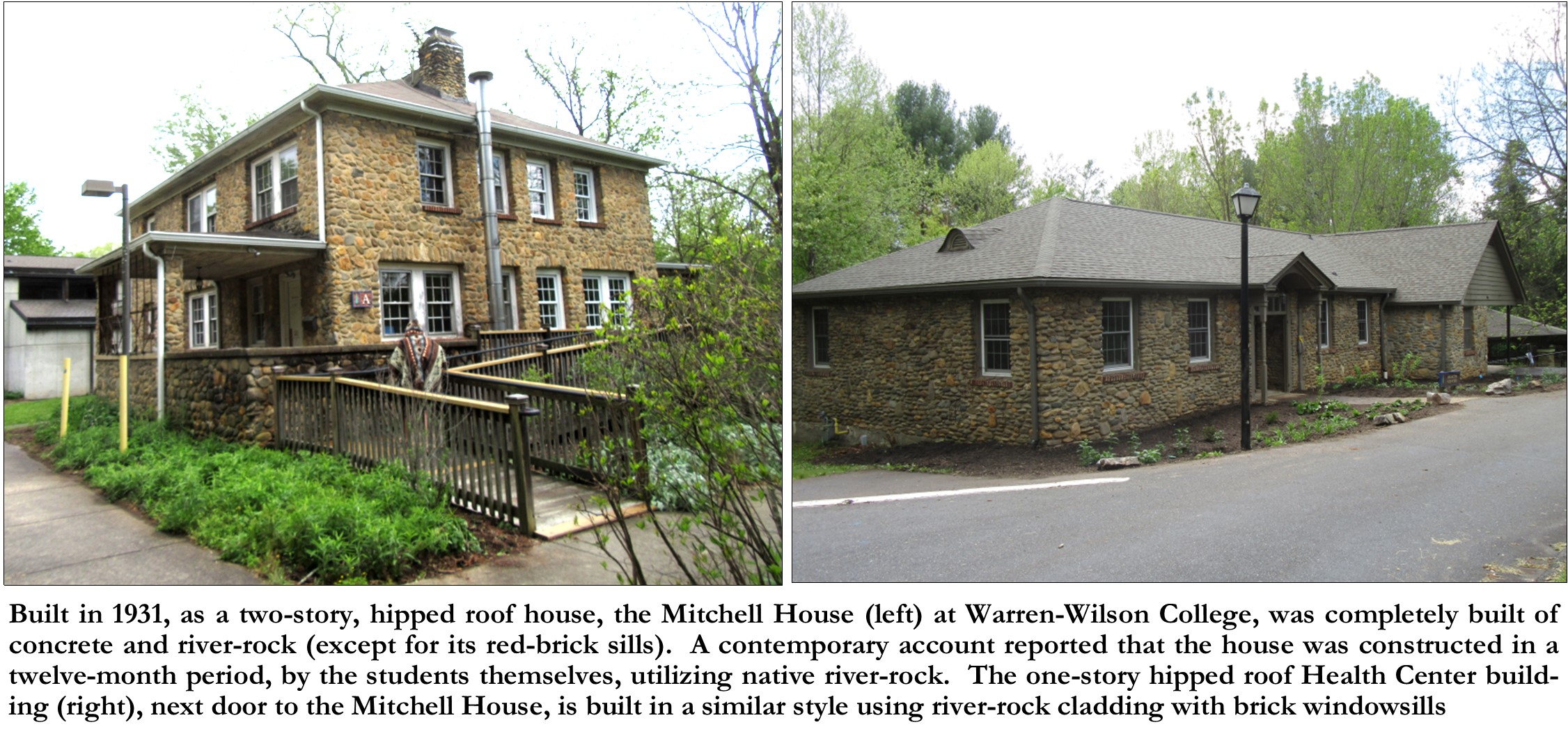

Further west of Grovemont, still in the Swannanoa area, is Warren-Wilson College, which was founded in 1894 as the Asheville Farm School. In 1931, the “Agnes Mitchell House” was completed and dedicated to serve as faculty housing. Built as a two-story, hipped roof house, the Mitchell House was completely built of concrete and river-rock (except for its red-brick sills). A contemporary account reported that the house was constructed in a twelve-month period, by the students themselves, utilizing native river-rock.[44] The rock was no doubt gathered from the Swannanoa River, which runs through the campus. Next door to the Mitchell house is the college’s Health Center. The building now known as the Health Center was built, largely by Farm School students, as the Murden Infirmary in 1925, the product of a $7000 gift in honor of Fannie J. Murden. In addition to two four-bed wards and two single rooms, the infirmary would provide “a general bathroom, a nurse’s room and bath, a kitchenette, a linen and supply closet and an office which can also be used as drug room and dispensary.” Most of the construction was done in 1926. In 1965-66, an addition was built which included an apartment for the nurse, ward space, and a carport.[45] The one-story hipped roof Health Center building is built in a similar style using river-rock cladding with brick windowsills. It’s obvious that some of the river-rock was laid by an experienced stonemason (perhaps in the later remodeling), as not only is the coursing of the rock more refined, but the many of the mortar joints were troweled in a grapevine pattern, only achieved by an experienced mason.

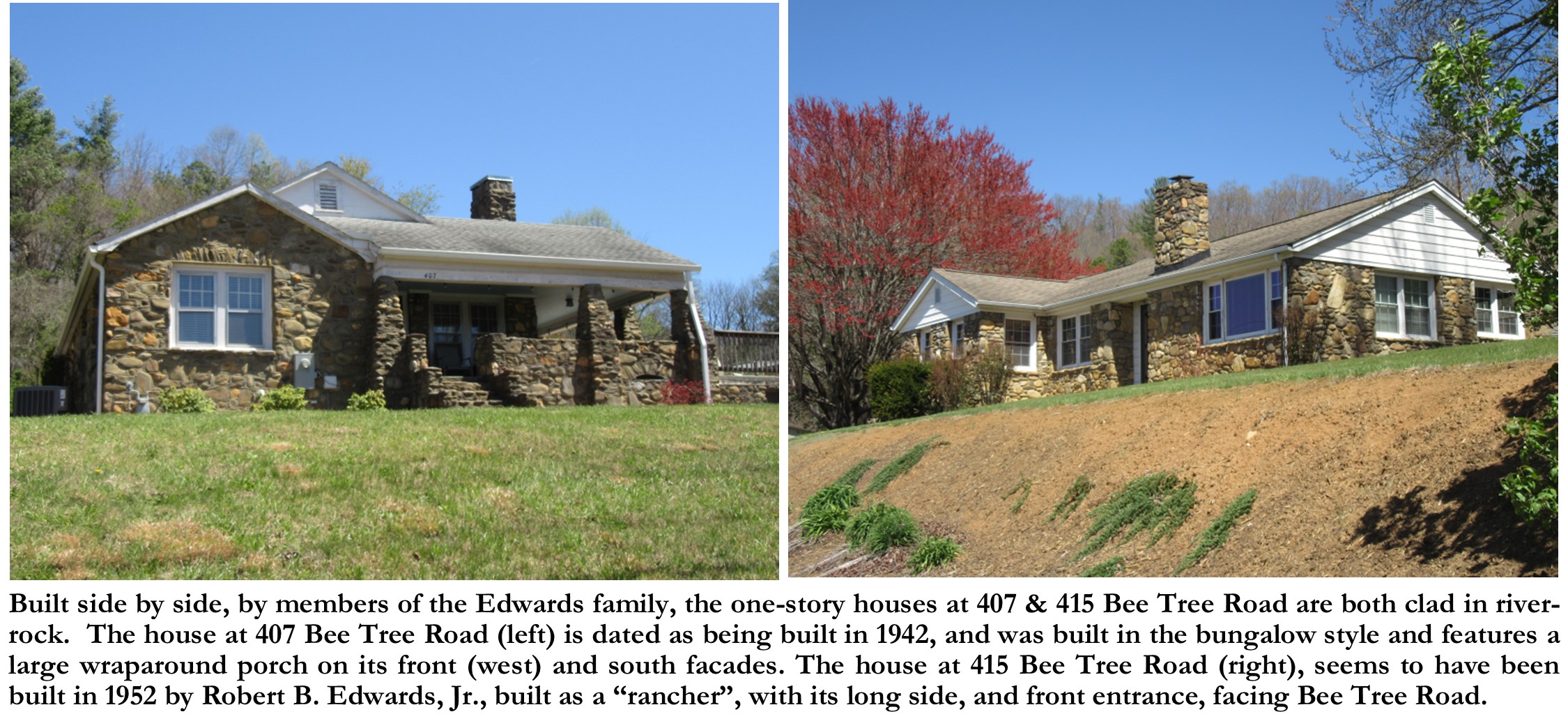

To finish our study of the river-rock building tradition of Black Mountain and Swannanoa, we bring our attention to two later examples of river-rock houses in Swannanoa. Built side by side, by members of the same family, the one-story houses at 407 & 415 Bee Tree Road are both clad in river-rock. Robert B. Edwards, Sr. bought the former Frank Jordan farm along Bee Tree Road in 1940.[46] At the time, Edwards was the superintendent of the Buncombe County Training School in nearby Leicester, NC, and primarily lived on that campus. Perhaps Edwards had plans to retire to the farm, however, he passed away in 1941[47], not but a year later. The farm with its original 1870’s farmhouse was inherited by his wife and family. The house at 407 Bee Tree Road is dated as being built in 1942 (on the county tax records), so it was either started by R. B. Edwards, Sr. before his passing, or else was built by his daughter and son-in-law, Elmer & Nesta (nee Edwards) DeBruhl, shortly thereafter. The house was built in the bungalow style and features a large wraparound porch on its front (west) and south facades. The house’s walls, porch columns and porch rails, and large side chimney, are all clad in various sized river-rock. The house at 415 Bee Tree Road, seems to have been built in 1952 (according to tax records) by Robert B. Edwards, Jr. It was built as a “rancher”, with its long side, and front entrance, facing Bee Tree Road. A large center river-rock-clad chimney sits on the top wall adjacent to the front entrance. As the Edwards farm borders the Swannanoa River (on its western property lines), it’s probable and highly likely that the river-rock came from their own property.

The river-rock building tradition, which had started in Buncombe County at Montreat in 1921-22, soon spread to nearby Black Mountain and Swannanoa, as we have evidenced in our study. Although not an exhaustive study, this should be sufficient to bring an awareness of the river-rock tradition in Black Mountain and Swannanoa and should form the basis for further inquiry into this unique building tradition.

Photo & Image Credits: (All photos by Dale Wayne Slusser, unless cited below.)

Anderson Auditorium-Officials & Building Crew- Image # C170-8, Pelton photo (A7419) of Montreat officials and building crew in front of the recently completed Anderson, 1922- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Grovemont-On-Swannanoa Map– Image #F037-DS- original map loaned for scanning from the Swannanoa Branch Library. Map titled “Townsite of Grovemont-on-Swannanoa / Founded 1924 by E. W. Grove- Buncombe County Special Collections.

Cover of the Grovemont-On-Swannanoa Sales brochure, c.1927– accessed from Grovemont Park, Swannanoa, NC website: https://grovemontpark.org/about-1-1

Existing Lake June Pier photo– by Allen Dye, Summer Street, Grovemont, Swannanoa, NC.

Vintage Lake June photo– Friends and Neighbors of Swannanoa website: http://swannanoafans.org/recent-news/swannanoa-stories/

[1] https://www.dictionary.com/browse/folk-art

[2] See: Cobblestone Quest: Road Tours of New York’s Historic Buildings, by Rich & Sue Freeman. (Englewood, FL: Footprint Press, 2005); And: Cobblestone Architecture, by Carl F. Schmidt. (New York: Published by Carl F. Schmidt, 1944).

[3] “The Effective Use of Cobblestones as A Link Between House and Landscape”, The Craftsman, 1908. This article was republished in Craftsman Homes: Architecture and Furnishings of the American Arts and Crafts Movement, by Gustav Stickley. (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1979), pages 102-108.

[4] “The Effective Use of Cobblestones as A Link Between House and Landscape”, in Craftsman Homes: Architecture and Furnishings of the American Arts and Crafts Movement, page 102.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Town of Black Mountain, Buncombe County, North Carolina: Architectural Survey” by Sybil Argintar- August 26, 2007, page 13. – https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll47/id/1448/

[7] “DISSOLUTION NOTICE”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 17, 1905, page 4. – “The partnership heretofore existing between W. B. Cordell, J. C. Cordell, H. S. Walton, A. B. Nix, under the firm name of Cordell Brothers & Company, has been by mutual consent dissolved. All business related to the firm will hereafter be attended to by W. B. Cordell and J. C. Cordell, under the name Cordell Brothers.” -newspapers.com

[8] See Draft Registration-ancestry.com; Also on a related U.S., Lists of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty, 1917–1918, “Local Board, Div. 1, Asheville, Buncombe County”, dated June 24, 1918, A list of the men selected to report to Camp Jackson, SC, “William H. Cordell” is listed, and his occupation is listed as “Woodsman”.-ancestry.com

[9] See 1920 U. S. Census- Ancestry.com

[10] 8/10/1925 N. D. & E. E. Weast to Jessie K. & Nora Peterson LOT 12 BLK 1 BK 154 P 61 Db. 309/494. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[11] 8/21/1925 (rec’d- 9/9/1925) J. K. & Nora Peterson to M. W. Dargan WEST MGN MIDLAND AVE BLACK MTN (LOT 12 BLK 1 BK 154 P 61) Db. 313/315.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[12] Asheville Citizen-Times, March 1, 1926, page 12.- newspapers.com.

[13] 04/16/1926 J. K. & Nora Peterson to D. C. & Lillian Russ WEST MGN MIDLAND AVE BLACK MTN (LOT 12 BLK 1 BK 154 P 61) Db. 342/176. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[14] 08/09/1926 D. C. & Lillian Russ to M. W. Dargan WEST MGN MIDLAND AVE BLACK MTN (LOT 12 BLK 1 BK 154 P 61) Db. 357/480. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[15] 6/4/1923 D. C. & Lillian Russ to J. K. Patterson, trustee, and M. W. Dargan (party of the third part) [D/T] MONTREAT RD Db. 165/ 17. (Indebted to M W Dargan for $1,080-Satisfied Aug 1925) -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[16] 3/25/1922 W. A. & Nan Burnette to H. D. & Maud Melton BLACK MOUNTAIN Db. 256/130. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[17] 12/12/1925 H. D. & Maud Melton to Gregg Swayer ALEXANDER ST BLACK MTN TWP Db. 325/81.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[18] “BUILDING APARTMENT”, Asheville Times, April 6, 1940, page 5. “Miss Annie Webb is building a four-room apartment building on Kentucky Road at Montreat. J. Gregg Sawyer is the contractor.”– newspapers.com.

[19] 4/28/1945 Robert K. & Jean G. Smith to J. A. & Laura Solesbee BLACK MOUNTAIN TWP Db. 581/419. “…Being Lot Nos.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, & 12…Block 6…Plat Book 154 on page 193…”. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[20] The Nottinghams purchased lots 5 & 6 in 1914 (See Db. 194, p. 23-Buncombe County Register of Deeds) and sold them in 1943, just two years before the Solesbees’ purchase, to J. B. & Beatrice Gilbert (See Db. Db. 550, p. 21-Buncombe County Register of Deeds).

[21] As recounted to me by J. A. Solesbee’s son, Ronald Astor Solesbee, of Asheville, NC in 2023.

[22] 1/1/1917 W. B. Dickson and wife to A. T. Griffin

[23] The Greensboro Patriot, Greensboro, NC, July 20, 1910, page 2. – newspapers.com

[24] 12/21/1931 John T. & Minnie Hunt to Mary G. Scarborough W SIDE CHURCH ST BLACK MTN Db. 444/588. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[25] “John T. Hunt, Dies At Greensboro Home”, The Charlotte News, Charlotte, NC, March 6, 1933, page 13. -newspapers.com

[26] 10/4/1915 (rec’d-11/29/1915) Methodist Colony Co. to Sallie F. R. Dusenberry (of Lake Como, FL) LOT 35 BLK 26 SEC 1 BK 154 P 193 Db. 194/123.

[27] “NOTICE OF SALE OF REAL ESTATE FOR TAXES, Town of Black Mountain.” Asheville Citizen-Times, August 22, 1938, page 2. “Mrs. M. E. Haight, Lot 346 Sheet 9, $14.40”. -newspapers.com

[28] Civilian Conservation Corps-was a work relief program that gave millions of young men employment on environmental projects during the Great Depression.

[29] https://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/historic-preservation-office/PDFs/ER_19-4972.pdf, page 4-7.

Nov 16, 2020 — The North Fork of the Swannanoa River Gaging Station (BN6393) was determined eligible for the NRHP in 2018.

[30] “Complete Municipality and All Improvements Now Planned by Grove”, Asheville Citizen-Times, June 15, 1924, pages 1-2. -newspapers.com

[31] “FIRST HOUSE IN GROVEMONT, BUILT BY E. W. GROVE, FOR SALE BY US”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 9, 1924, page 35. -newspapers.com

[32] Ibid.

[33] “THE STONE HOUSES AT GROVEMONT”, The Asheville Times, February 15, 1925, page 27. -newspapers.com

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] “THE STONE HOUSES AT GROVEMONT”, The Asheville Times, February 15, 1925, page 27. -newspapers.com

[37] “Editors on Visit to Grove’s Project”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 5, 1924, page 18. -newspapers.com

[38] Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/alluvial%20plain

[39] Ibid.

[40] Virginia & Lee McAlester, A Field Guide to American House Styles. (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984), p. 26.

[41] “THE STONE HOUSES AT GROVEMONT”, The Asheville Times, February 15, 1925, page 27. -newspapers.com

[42] “Grovemont On Swannanoa”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 20, 1926, page 12. -newspapers.com

[43] See the Fox Creek Park website for more information: https://foxcreekpark.org/

[44] “New Faculty House At Farm School Dedicated”, Asheville Citizen-Times, October 28, 1931, page 8. -newspapers.com

[45] This information compiled by Brian Conlan, Director of the Pew Learning Center and Ellison Library at Wilson-Wilson College, Swannanoa, NC from the Warren-Wilson Archives.

[46] 01/11/1940 Frank M. & Emma Jordan to R. B. Edwards SWANNANOA Db.521/411. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[47] EDWARDS RITES WILL BE HELD THIS AFTERNOON”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 21, 1941, page 3. -newspapers.com