by Dale Wayne Slusser

Montreat started in 1897 as a summer religious conference ground. Now after 125 years, Montreat has evolved into an incorporated town within which lie not only the religious conference ground, but also a Christian liberal arts college, a Presbyterian heritage center, among other separate entities, as well as several hundred homeowners. These homeowners and institutions all share a common heritage and tradition. One of those traditions, which was spawned in the early 1920’s during the administration of Dr. Robert C. Anderson, is the tradition of using “river rock” masonry construction on Montreat’s institutional buildings, cottages, and landscape features. This building tradition, although originating in England centuries past, was for Montreat a product of the proliferation of the American Arts & Crafts tradition of the early twentieth century. What is “river-rock” and what are its origins, both in architectural history as well as at Montreat?

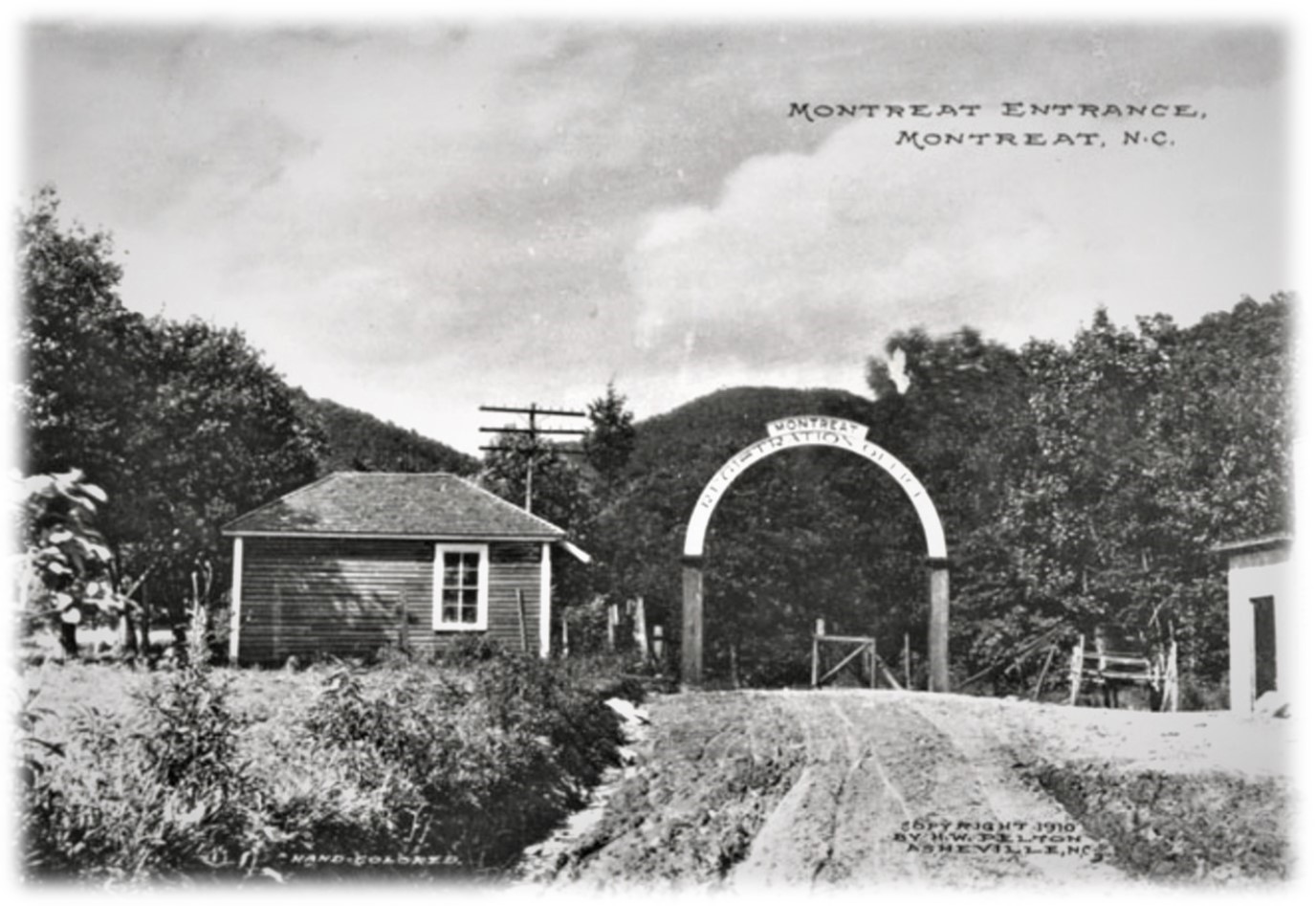

A brief history of Montreat is warranted to give background and context to the story of the development of Montreat’s unique “river-rock” building tradition. In 1897, Rev. John C. Collins, a Congregational (Puritans) minister of New Haven, Connecticut, along with other associates from other religious denominations, formed an association for the purpose of establishing a religious assembly ground as a “health and rest resort”[1], as well as a place for religious education. Their idea was to establish a “colony similar to that of Ocean Grove, New Jersey”, except that they desired it to be more like a Great Adirondack Camp, rather than a noisy seaside resort. Surprisingly, although the group was made up of almost exclusively members from the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic States, instead of choosing a site in Upstate New York (such as the Adirondacks) or New England, they chose to establish their new colony in the mountains of Western North Carolina. No doubt, they chose the mountains of Western North Carolina because of its healthful and mild climate. In March of 1897, a Charter was obtained from the North Carolina General Assembly for the establishment of the “Mountain Retreat Association”, which shortly thereafter adopted the contracted moniker of “Montreat”. The association purchased a “large and beautiful tract of land comprising about 4,500 acres of virgin forest mountain land situated about sixteen miles east of Asheville, North Carolina, two miles north of Black Mountain Station, on the headwaters of the South Fork of the Swannanoa.”[2] The Mountain Retreat Association under the leadership of Rev. Collins, hired a surveyor/engineer, in 1897, to layout lots for the new community. “Mr. Collins “leased for 99 years about three hundred of the lots that have been laid out and applied the proceeds to assist in paying the original purchase price of the land”.[3] At first, the conferees to the summer conferences were housed and served their meals in tents and held their assemblies in a rustic open-air mountainside amphitheater. However, soon “cottagers” began building picturesque rustic “cottages” on their purchased lots for lodging and then a wooden auditorium and permanent dining and cooking facilities were built. Much of development of the early years, such as the building of Montreat’s first hotel, was bankrolled and accomplished through the generosity of famed candymaker, John S. Huyler.

Fast forward our brief history of Montreat to 1905. Rev. J. R. Howerton, pastor of First Presbyterian Church, Charlotte, North Carolina, who had been spending his summers at Montreat for many years, conceived the idea “of forming a company and buying Montreat for “the constituency of the Presbyterian Church to be used in the summer season for Bible Study, lectures, theological schools, Chautauqua, and the like”.[4] That same year, Howerton with the support of others in the denomination obtained a purchase option on the Montreat property for one year-for $50,000-the cost price less interest, was given by Mr. John Huyler to Rev. J. R. Howerton, D. D., provided the Presbyterian Church in the United States would undertake to carry into effect the original plan of making Montreat into a religious and educational institution”.[5] In 1906, Rev. Howerton presented his idea to the General Assembly, wherein the Assembly formed an appropriate committee and appointed Howerton as the chairman of the committee. The purchase option was only binding until September 1, 1906, by which time half of the purchase price, amounting to $25,000, had to be paid to Mr. Huyler, with the remaining to be paid off within 10 years. To raise the necessary funds, the Committee devised a plan whereby they would issue $500 shares of stock in the Montreat Retreat Association at $100 per share. One purchased share would entitle the stockholder to one lot, with the stipulation that no one stockholder was to purchase/own more than one share. The sale of stocks would result in a net sum of $50,000, with $25,000 of that sum to be paid to Huyler as the required down payment, and the remaining funds to be devoted to improvements that would benefit all, such as roads, sewer system, power plants, electric lights etc. “In the Fall of 1906 Dr. Howerton employed Lockwood, Green & Co, architects and engineers of Boston, Mass. to survey the Montreat grounds and to lay off 1,177 lots, including the lots previously laid off by Mr. Odell (in 1897), as shown by maps recorded in the Office of the Register of Deeds of Buncombe County”.[6] Of course the question arose as to how to assign which lots to which stockholders. To answer the question a meeting of the stockholders was held in the old Montreat Hotel in January of 1907, at which time the “stockholders themselves by vote determined the method of procedure in selecting those lots”.[7] An ingenious and effective plan was devised and executed, whereby “numbers up to the total number of stockholders were placed in a basket on slips of paper, and each stockholder drew one slip of paper”.[8] The number on the slip of paper drawn by the stockholder represented his position in selecting his/her choice of lots. After each of the stockholders had picked a number, the meeting then adjourned to another room where a map of the available lots (of course the lots that had been purchased prior to 1906, were not available for selection as they were already “owned”) was hanging on the wall. Committee members A. L. James and R. C. Anderson were present in the room to make sure that the order of selection was maintained (according to the number selected from the basket), as well as to record and verify each selection. R. C. Anderson later recalled that it was exciting to see the stockholders running through the forest looking for what lots they may want to select when their time came. Of course, as Anderson writes: “that those drawing the numbers of lower denomination had greatly the advantage over those drawing the high numbers. First choice was very different from the 500th choice.”[9]

By 1907, Montreat was in the hands of the re-incorporated Mountain Retreat Association and Dr. Howerton was elected as the director. Although the stockholders were not required to be members of the Presbyterian Church of the United States denomination, to insure that Montreat would be primarily available for use of the denomination’s congregations and work, the amended charter of the organization “provided that the Board of Directors of the Association should not be less than 25 nor more than 50, two-thirds of whom should be officers in the Presbyterian Church, U. S.”. Dr. Howerton only remained as the director for one year, at which time he was replaced by Judge J. D. Murphy. Unfortunately, by then it was clear that the new Association was “under the burden of debt and liabilities accumulated the first year”,[10] as not only were they under the debt of the original purchase option, but Dr. Howerton had also incurred debt in making the necessary improvements (roads etc.) and building a new wooden hotel, called “The Alba”. A large portion of the debt was held by Mr. John Huyler, so in 1910 a committee was formed and Mr. C. E. Graham (more about him later) one of the Directors was appointed to meet with Mr. Huyler to devise a plan to help pay the Association’s indebtedness. Mr. Huyler in return made the generous offer that if within the ensuing year, the four Boards (Committees) of the Presbyterian Church, U. S. would pay off all the indebtedness, except that part of the indebtedness owed to him, and also provide an additional $10,000 for improvements and working capital, that in return Huyler would cancel all the indebtedness owed to him and he would also return and deliver to the Association any shares of stock in his possession (which the Association could resell to new stockholders). By 1910, the Association realized that it seemed unlikely that they would be able to meet Mr. Huyler’s terms, due to several factors such as the Church boards’ inability (or unwillingness) to provide their share. A meeting was called and held by the Managing Committee on August 16, 1910 at the Montreat office, then a one-room log cabin. The Committee whose task was to “devise ways and means, if possible, to save Montreat.”[11] A plan was rapidly devised whereby each stockholder was asked to pay a one-time assessment of $30 per share to pay off the Association’s indebtedness, and if they were unwilling or unable to pay the assessment, they were required then to surrender their shares back to the Association to be sold at $30 per share to another stockholder. Long story short, aside of a few hiccups, the plan worked, and by 1911 all the indebtedness had been paid off, and on August 11, 1911, Judge Murphy resigned as President and was elected as the Vice-President, with Rev. Robert C. Anderson, who had been instrumental in carrying out the plan to erase their debt and put Montreat onto a solid financial footing, was elected President. It was then that the story of the river-rock building tradition of Montreat really began.

By 1919, the numbers of private owners building their own cottages, as well as the increased conference and retreat attendees was burgeoning, prompting the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church to begin a capital campaign to raise “$200,000 for the enlargement and better equipment of Montreat”.[12] The increased usage of Montreat, as the 1920’s dawned, was perhaps because of the proliferation of the automobile, and “the vacation”. “Vacation” was a result of the work of labor unions to improve conditions for workers. Beginning in the 1860’s labor unions and employees started calling for an eight-hour workday and five-day workweek. In 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant issued a proclamation that guaranteed a stable wage and an eight-hour workday — but only for government workers. Grant’s decision encouraged private-sector workers to push for the same rights.[13] Although a few private businesses began to slowly adopt the 40-hour workweek, it wasn’t until 1916 that that Congress passed the Adamson Act, a federal law that established an eight-hour workday for interstate railroad workers. The Supreme Court constitutionalized the act in 1917.[14] Although it would not be until 1938, that Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which limited the workweek to 44 hours, and not be until 1944 that Congress amended the Fair Labor Standards Act (limiting the workweek to 40 hours) by the 1920’s more private companies had begun to initiate the shorter workday and workweek. Combined with the establishment of “vacations” for the middleclass and working people, was the rise of the affordable automobile. “Ownership of motorcars rose from 0.5 million in 1910 to more than 8 million in1920 to 26.5 million in 1925, and the declining cost of the automobile meant that middleclass Americans were more able to afford one.”[15] Now, the rising middleclass not only had affordable places to escape to on their “vacations”, such as the rising National Parks, and conference and retreat centers, but with the affordable automobile, they now had a viable means of getting there and back.

“MONTREAT AUDITORIUM COSTING ABOUT $10,000 IS NEARING COMPLETION”[16], announced the July 11, 1921 edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times. Besides the size of the auditorium, which was designed to seat 5,000, and its unique hexadecagon (16-sided polygon) shape, a prominent and distinctive design element was its “river-rock” cladded round columns and exterior walls. The above-mentioned article from 1921, gives a good description of the “river-rock” finish. The reporter tells us that the exterior was “finished in waterworn brook stones taken from streams on the mountainside near Montreat”, which “are laid in cement”.[17] Although in Western North Carolina these “waterworn brook stones” are known as “river-rock”, technically speaking, the stones used on the new auditorium were of the middle category of “river-rock” and are called, cobbles or cobblestone. “River-rock is categorized into three categories, based on its size, pebbles (smallest size), cobbles or cobblestone (small stones), and boulders (large stones).

Fund raising for the new auditorium, which would be named “Anderson Auditorium”, began in 1919, however, construction was not begun until November of 1920, with completion of construction in the Spring of 1922.[18] Architect Richard Sharp Smith, a Britisher who first came to Asheville around 1895 while he was working on the Biltmore Estate as an employee of architect Richard Morris Hunt, was hired by Anderson to take Anderson’s sketches for the new auditorium and turn them into working drawings. Interestingly, the two notable features of the new auditorium, the round columns, and the use of cobblestones, were not part of the original design of the auditorium, yet both features would become a standard building pattern or tradition for Montreat buildings and landscape features. Rev. Anderson tells us how both features came to be part of the design:

“Mr. Smith first thought it best to have the building erected with Montreat stone blocks and to have the pillars designed built in square form, but this type of stone work at the time was too expensive. I employed local men and tested out the round column, instead of the square, to be erected with small cobblestones taken from the bed of the creek. The square columns with the large stone were estimated to cost about $35 a square yard. By actual tests it was found that the round pillar could be built by using a round form and the small cobblestone at a cost of about $10 per square yar, so we decided to use this form for the structure of the columns which now stand in the auditorium.[19]

R.C. Anderson recounts that the construction of the auditorium, was under his direct supervision, but that “Mr. Charley Godfrey of Black Mountain was employed as foreman and did a fine work in directing the construction of this building under the supervision of Mr. Smith [Richard Sharp Smith, architect] and myself”.[20]

The auditorium was complete by the summer conference season of 1922. One astute Montreat cottager who was from Gaston County, North Carolina, and no doubt a former parishioner of Rev. R. C. Anderson when Anderson was the Presbyterian minister at Gastonia, prior to his appointment to Montreat, was so enamored with the ongoing progress at Montreat, that the cottager felt incumbent to make a full news report back to Gastonia. “R. C. Anderson is a wonder”, reported the Gastoniaian cottager in the July 26, 1922 edition of the Gastonia Gazette, “He has done for Montreat what no other man of North Carolina could have done, but perhaps the crowning glory of it all is this new auditorium. It is built of cobblestones up to some height, and they show inside and out. The circular roof rises to a great height and is braced by steel girders and rods and there are many windows. There are also charming rustic seats, and the great beauty of it all was, that it was built by mountain workmen and not one accident occurred and not one man was hurt in the building. The whole auditorium is unmarred by any trouble, and now it is almost paid for.”[21] Like the letters of the Apostle Paul, the correspondent ends the report with salutations from the Montreat “apostle” himself, “Rev. & Mrs. R. C. Anderson are as delightful as ever and as interested in their old home and friends in Gastonia, and always ask of them.”[22]

But where did Anderson get the idea of using cobblestones? Although I don’t know for sure where he got the idea, I have my suspicions of possible reasons and possible influences which may have led to his decision. First, one merely has to visit Montreat, as I did one day, and you will hear and see the reason! While touring Montreat looking at houses and landscape features, in preparation for this article, I experienced what could be termed an epiphany. As I stepped out of the car at one of our stops, I heard the loud thundering of cascading water. The sound was not like that of a babbling creek, but more like a roar of rushing water. I turned toward the sound and saw that we had just come across a small bridge over a creek. I ran to the bridge and looked over, and there was one of the numerous creeks that come from springs in the mountains above Montreat, which tumble down the hillside, bringing along bits of rock from the mountainsides. Along the shallow bottom and sides of creek I noticed many “water-worn stones” that continue to be supplied (though probably at a greatly diminished quantity) to the Montreat cove. The steepness of the creeks and the abundance and volume of water that flow down the creeks, is such that the rocks or stones that are carried along on the bottoms and sides of the creek, are rubbed smooth by the rushing water, much like the gemologist’s rock tumbler which using water and grit and “tumbling”, raw rocks turn into smooth, rounded, polished stones. So, just the quantity and availability of an inexpensive, as well as decorative, building material onsite, may have inspired Anderson to consider using “river-rock”, which in this case were mostly cobblestones.

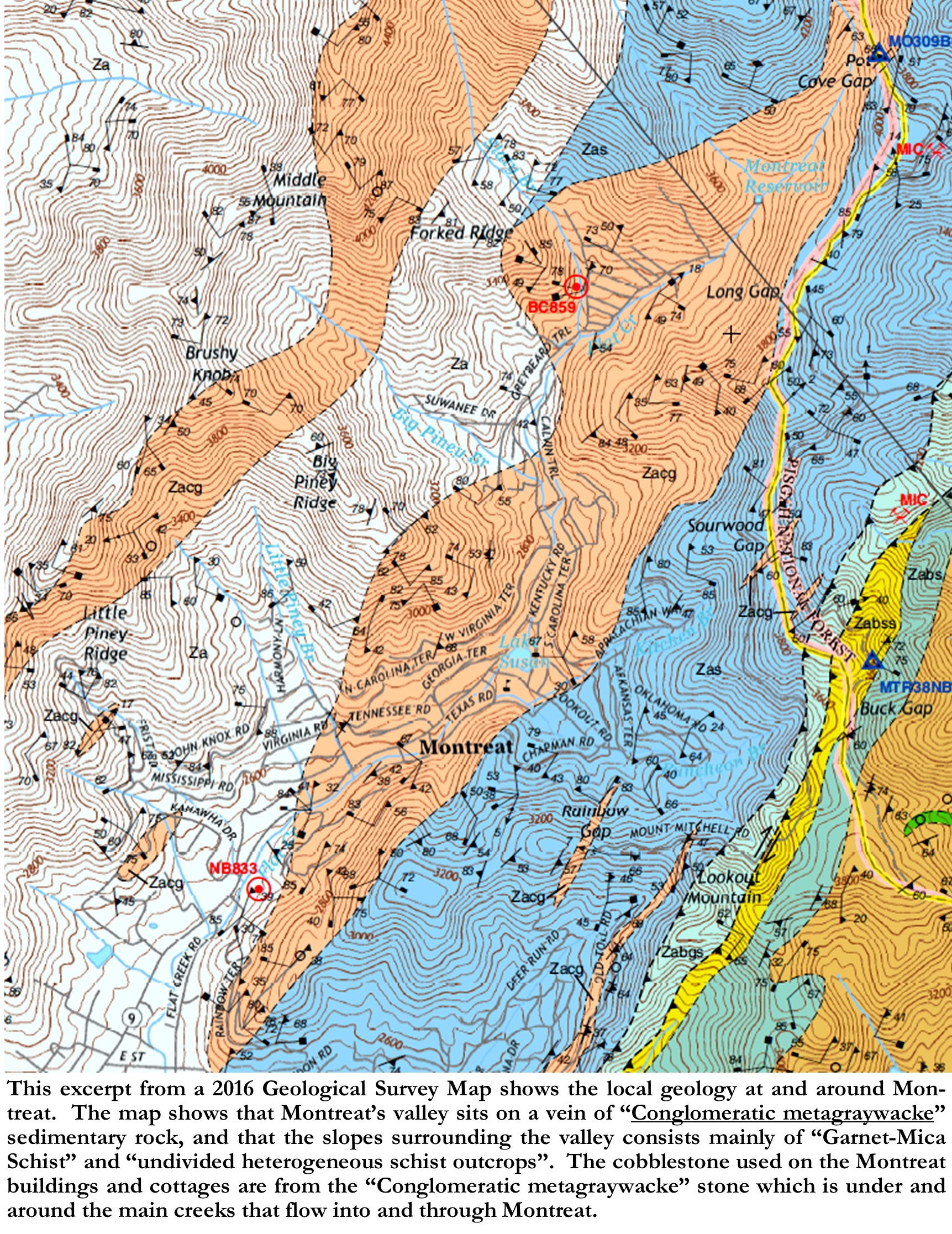

Why did/does Montreat have such an availability of stone, especially river-rock and cobblestone? The short answer is – because of the type of rock upon which Montreat sits. Geologists who have surveyed and documented (mapped) the local geology at and around Montreat, tell us that Montreat’s valley sits on a vein of “Conglomeratic metagraywacke” sedimentary rock, and that the slopes surrounding the valley consists mainly of “Garnet-Mica Schist” and “undivided heterogeneous schist outcrops”. The cobblestone used on the Montreat buildings and cottages are from the “Conglomeratic metagraywacke” stone which is under and around the main creeks that flow into and through Montreat. Geologists tell us that the cobblestones used at Montreat are mostly mineral quartz, and not the less easily broken minerals like the micas and the metamorphic minerals kyanite, andalusite, and sillimanite, which would easily be broken up or dissolved in the water in the creeks and rivers. However, the cobblestones at Montreat do contain some of those other minerals, but because the minerals in the “Conglomeratic metagraywacke “at Montreat have metamorphosed (mineralogical and structural adjustments of solid rocks to physical and chemical conditions differing from those under which the rocks originally formed) due to subsequent continental scale collisions of the plates of “Conglomeratic metagraywacke”, that the metamorphism has caused the preferred texture or foliation to the rock (perpendicular to the applied stress during mountain building) and so results in unequal weathering and breakdown of the broken fragments of the rock when tumbled by the streams.[23] The metamorphism of the minerals is akin to the hardening of iron to make steel, which makes for a stronger material. The other type of stone, “Garnet-Mica Schist”, was also used for buildings at Montreat, later in the 1930’s and 1940’s (as the supply of local cobblestones diminished), but they are larger, flatter and have sharp broken edges and are laid in a coursed rubble pattern. This article, however, focuses on the cobblestone building idiom at Montreat, which mainly covered the period from 1921-1929.

The cobblestone building tradition is an ancient building tradition which goes back ages and originated in Europe and Britain. Cobblestone masonry originally and most often was part of the folk-art vernacular style of architecture. “Folk Art” is defined as: “produced typically in cultural isolation by untrained, often anonymous, artists or by artisans of varying degrees of skill and marked by such attributes as highly decorative design”[24], thereby making it a building tradition that was developed and proliferated mostly by “artisans” (masons and country builders-not architects) and most often limited to small locales.

Although the cobblestone tradition began ages ago, originating in Europe and Britain, as far back as the Romans (at least), unlike the building traditions and styles from the 1600’s, like manor houses and Tudor building traditions, and the Georgian and Classical styles of the 1700’s, the cobblestone building tradition did not immediately take hold in America. In fact, the first noticeable use of river-rock, specifically cobblestone, in the United States did not begin until the 1830’s and 1840’s, and then was only isolated to a small pocket of locales surrounding the Finger Lakes in upstate New York. According to authors Rich and Sue Freeman, whose book, Cobblestone Quest: Road Tours of New York’s Historic Buildings, “the location and mason of the first cobblestone building [ in America] remains a mystery”.[25] Studies show that the epicenter of the beginning of cobblestone building in America was south of Lake Ontario, in Upstate New York. “What is known, is that cobblestone buildings began on farms and later migrated to the villages. It remained a predominantly rural construction method [building tradition] with only a small number being built in villages”.[26] This cobblestone tradition in the U. S. was mainly isolated to the New York State area, however it did spread slowly, but not prolifically, to other areas in the United States most exclusively through migration, with new settlers bringing their building traditions from the East to their new locales (Western and Southwestern Territories and California).

Evidence that the cobblestone building tradition is not a “style” is that in England and Europe it was used mainly on Georgian-style houses, but in America it was used on the later Greek-Revival style of the 1830’s through the 1860’s. Although the cobblestone buildings first built in America utilized small, rounded cobblestones (left behind by glaciers not in active creeks and rivers), they did not use cobblestone for the entire facing of the exteriors, rather the cobblestones were used in between dressed quoins (squared cornerstones).

But the use of and the way the cobblestone building tradition was used at Montreat, is more directly related to the resurgence of the cobblestone building tradition by designers and architects of the American Arts & Crafts/Mission-Style beginning around the turn of the twentieth century. By the nineteen-teens, the spread and proliferation of the American Arts & Crafts Movement was highly publicized in building catalogs and building magazines of the day. The American Arts and Crafts Movement promoted the use of local and honest (i.e.: natural) materials for building. This played well into Montreat’s original design idiom of the Rustic Revival which it had adapted from Montreat’s beginnings in the late 1890’s, which also promoted the use of natural and local building materials. However, a few designers and architects who promoted the Shingle-style architecture of the late 1800’s, did experiment in using cobblestone. Architect E. G. W. Dietrich, in the April 1887 edition of the Builder and Woodworker magazine, wrote an article simply titled, “Cobble Stone Building”.[27] “Cobble stones when laid with care make as durable a wall as any carefully selected building stone, and for a country residence cannot be surpassed in beauty,”[28] architect Dietrich told his readers. “The use of cobble stones have not been adopted in this country to any great extent”[29], Dietrich further told his readers, because of two reasons, which he says are: “the scarcity of such in some localities,” and the “inexperience with the use of such for masonry.”[30] However, Dietrich told his readers, that cobblestones “when laid with some care in reference to color, the result is very pleasing, more so than that gone over in many instances with mason’s tools or a painter brush”. This use of natural materials for giving color and texture was also used by architects and builders of the Arts & Crafts/Mission-style movement, and in fact, this movement was mostly responsible for the resurgence of the use of “river-rock” and cobblestones in the early twentieth century.

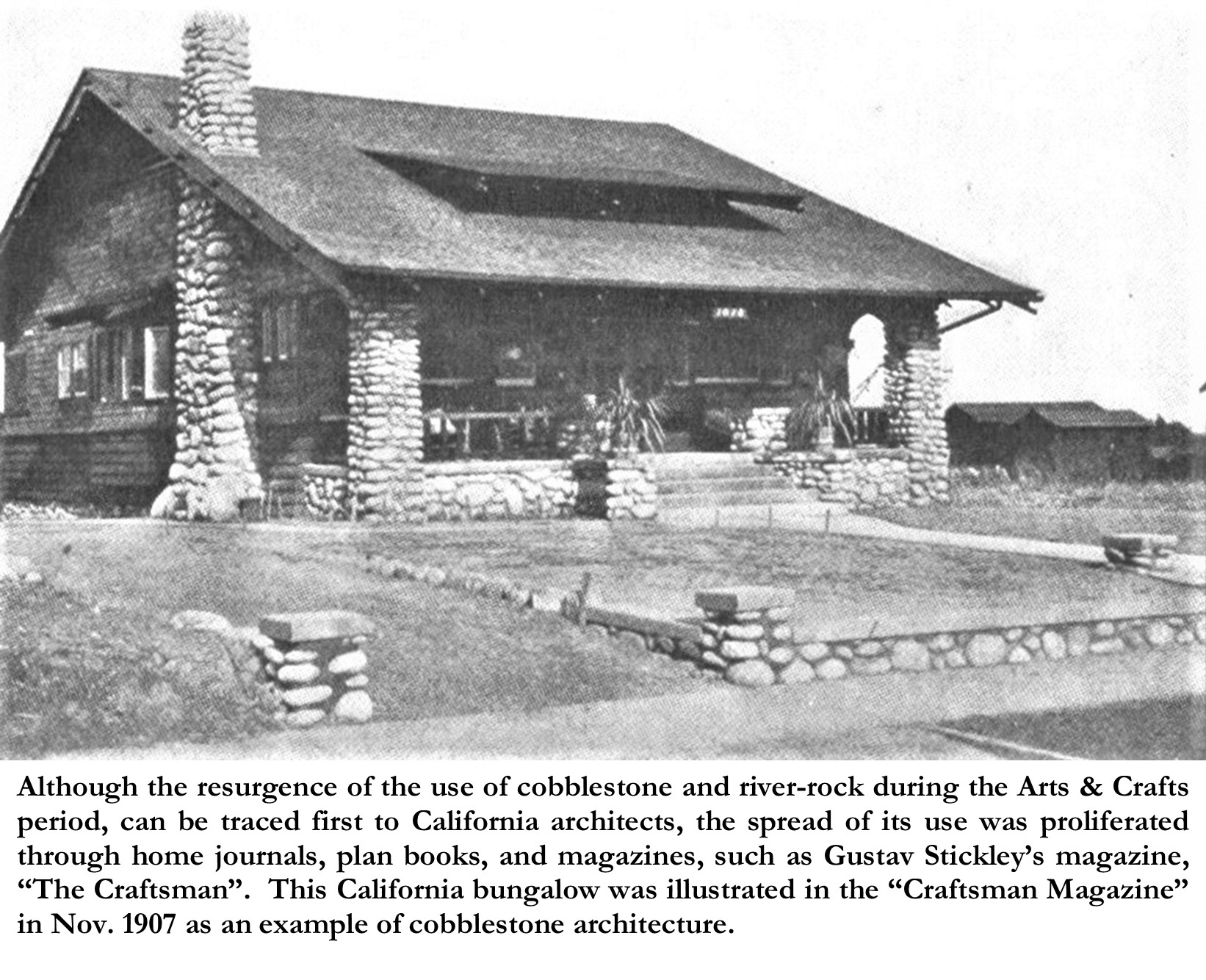

Although the resurgence of the use of cobblestone and river-rock during the Arts & Crats period, can be traced first to California architects such as Greene and Greene, the spread of its use was proliferated through home journals, plan books, and magazines, such as Gustav Stickley’s magazine, “The Craftsman”. In a 1908 edition of The Craftsman, Stickley wrote an article titled, “The Effective Use of Cobblestones as A Link Between House and Landscape”, where he promoted the use of cobblestones in building “modern country homes”.[31] Stickley confesses in the article, “We have never specially advocated the use of cobblestones in the building of Craftsman houses, for as a rule we have found that the best effects from a structural point of view can be obtained by using the split stones instead of the smaller round cobbles”.[32] “Nevertheless,” concedes Stickley, “ the popularity of cobblestones and boulders for foundations, pillars, chimneys and even for such interior use as chimney pieces, is unquestioned and in many cases the effect is very interesting”.[33] Ironically, Gustav Stickley states that “the best examples of this natural use of boulders and cobbles” comes from California, although Stickley was writing in Upstate New York close to the epicenter of where the first uses of cobblestones for houses in America were located. Crediting the use of cobblestones to Japanese architecture, Stickley goes on to give descriptions accompanied with photos of the “effective use of cobblestones as a link between house and landscape”. No doubt, by the 1920’s, like most Americans, Anderson was familiar with the Arts & Crafts Style. In fact, I know he was, as he chose to build his Montreat residence as a Craftsman bungalow in the rustic style, blending elements of the Rustic-Revival, like its log rails and stone porch piers, steps, and walkways, with elements of the Arts & Crafts style.

Whether it was originally intentional of R. C. Anderson, or whether it just naturally developed as he continued his “improvements”, is difficult to ascertain, however the use of round columns and especially the use of cobblestones was quickly adopted as the distinctive design idiom for subsequent institutional buildings and landscape features at Montreat. Of course, many of these buildings and landscape features (terrace walls, gate posts and bridges) were built in the 1920’s-1940’s immediately on the heels of the construction of the new auditorium, and all were under the leadership of Rev. R. C. Anderson.

After the construction of the auditorium, Anderson began other building projects, the next being the construction of a stone Gatehouse and Gate at the entrance to Montreat. Being an adroit fund-raiser, Anderson was able to find donors, sometimes wealthy individuals, and sometimes a group of individuals, to bankroll his various projects. In 1923 the Women’s Auxiliary contributed $2,000 for the construction of the new gate and gatehouse. Not only was the gate and gatehouse constructed using cobblestones, but also the round cobblestone-clad columns, designed by Anderson for use on the auditorium were also used on the four corners of the double-arched gate. Evidence of the cobblestone building tradition coming from the decorative folk-art vernacular building traditions shows distinctly on the gate, where lighter colored stones were used to spell, “MONTREAT” in the wall of cobblestones, above the front arches of the gate. Lighter colored cobblestones were used also to line the top edge of the arched parapet, as well as to outline each drive-through arched opening. This “painterly” use of the stones and cobblestones was a product of the decorative arts.

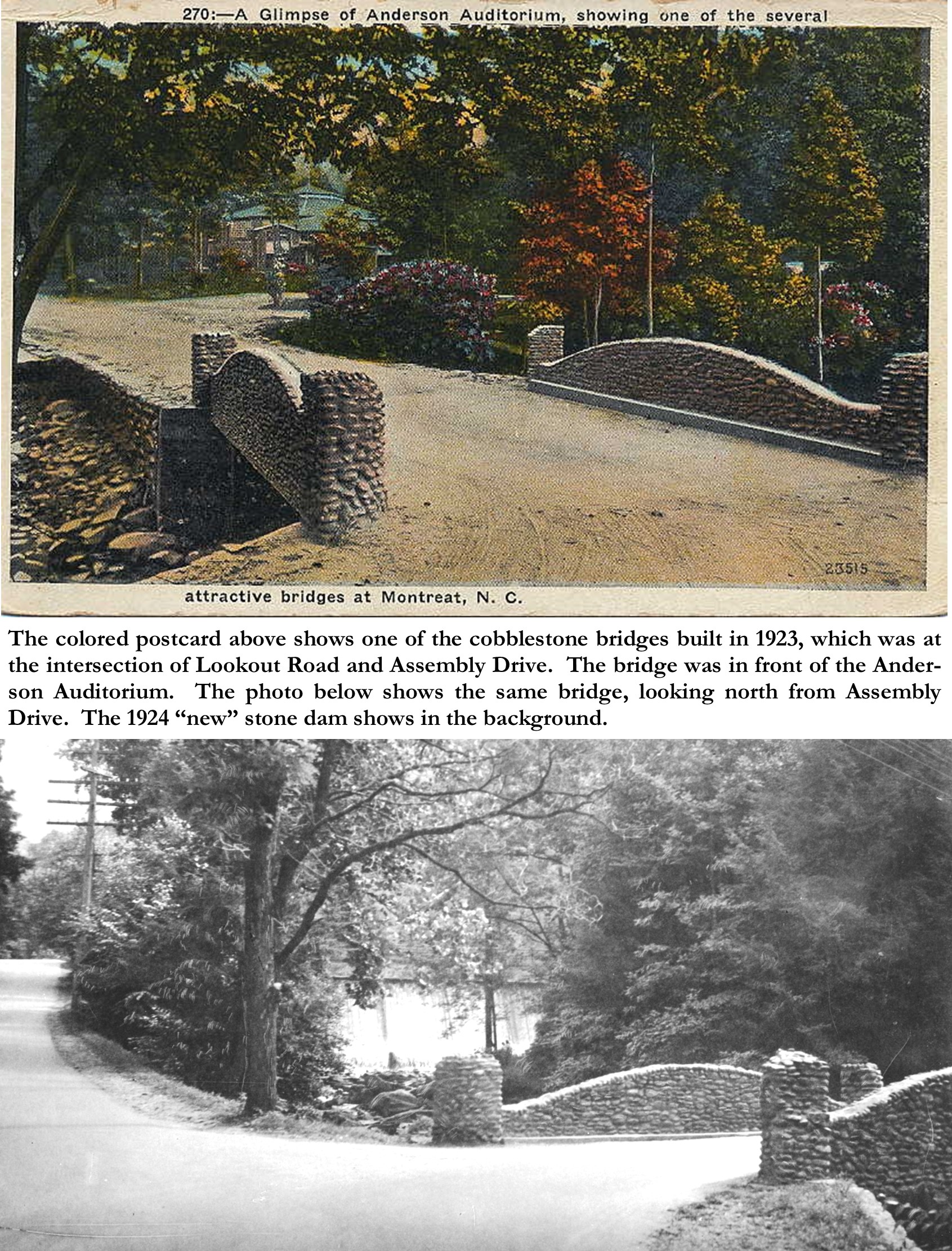

Also, around 1923, the use of cobblestones for landscape features began when Anderson solicited funds from Mrs. C. E. Graham of Greenville, South Carolina to build two concrete bridges below the lake-one just below the lake and the other in front of the new auditorium.[34] “Mrs. C. E. Graham” was Susan Jordan Graham, the wife and recent widow of a wealthy cotton manufacturer, Charles E. Graham, who had passed away in 1922. C. E. Graham, prior to moving to Greenville, SC had previously “resided in Asheville where he was first engaged in the wholesale business and later established the Asheville Cotton Mills, the first cotton manufacturing industry of this city [Asheville, NC]”.[35] In 1904, C. E. Graham purchased the old Vardry McBee/Camperdown Mill No. 2 in Greenville, SC, which he re-opened, specializing in the production of gingham and plaid fabrics. By 1907, Graham had expanded the mill and increased the accompanying mill village’s residential population to 1,200. The mill was successful through Graham’s death in 1922, and then in the hands of his son, Allen, until the Great Depression in 1930 forced the son into bankruptcy.[36] Remains of the old Vardry McBee/Camperdown Mill No. 2 still exist at the Reedy River Falls in the Falls Park Place in downtown Greenville.

“It was in the Spring of 1924,” recollected Rev. R. C. Anderson in 1947, “that Mr. Allen Graham of Greenville, SC, and Mrs. C.E. Graham, his mother, gave $25,000 with which to build the concrete dam and bridge in place of the old wooden dam forming what is now Lake Susan.”[37] The “old wooden dam” had been patched and limping along since the Flood of 1916, which had torn it apart. The new lake formed by the new and enlarged dam, at the request of Mrs. C. E. Graham was named “Lake Susan”, for as R. C. Anderson recalls: “Mrs. Graham’s name was Susan, her daughter’s name was Susan, her mother’s name was Susan, and her granddaughter’s name was Susan”.[38] The plans for the new dam were prepared by W. C. Whitner of Rockhill, SC, who because he was a Montreat Board Member, provided the engineering drawings at no-cost.[39] William Church Whitner was a professional civil engineer who was also a Montreat “cottager” (homeowner/resident), who in 1906 had designed the first wooden dam for the lake at Montreat.[40] Again Anderson hired Charley Godfrey of Black Mountain as the foreman of a local labor crew to build the new dam. Although the dam was primarily built of casted reinforced concrete, cobblestones were used to line the ends of the wing wall buttresses which supported it, as well as used extensively for the stone walls which were built to enclose the edges of the enlarged lake. A new dam has since been built replacing this 1924 dam, which was damaged during a 1940 flood, using flat fieldstones for facing, however remnants of the cobblestone walls surrounding the lake remain to this day.

Being empowered by the General Assembly’s endorsed 1919 building campaign, supplemented by his successes in raising donated funds for his first projects (Auditorium, new dam, and bridges) Rev. Anderson continued his “building and equipment improvements” into the mid-1920s. Anderson’s momentum had been accelerated in January 1924, when the Montreat Hotel was destroyed by fire. However, the monumental project of rebuilding the hotel would be long and arduous, and by necessity would have to wait for the completion of other projects already in the works.

Being empowered by the General Assembly’s endorsed 1919 building campaign, supplemented by his successes in raising donated funds for his first projects (Auditorium, new dam, and bridges) Rev. Anderson continued his “building and equipment improvements” into the mid-1920s. Anderson’s momentum had been accelerated in January 1924, when the Montreat Hotel was destroyed by fire. However, the monumental project of rebuilding the hotel would be long and arduous, and by necessity would have to wait for the completion of other projects already in the works.

In the Fall of 1924, while the debris from the fire was cleared from the hotel site, awaiting further development, construction began on a new building for the summer use of Executive Committee of Foreign Missions. The building was named the Richardson Foreign Missions building, with funds donated by Mrs. L. Richardson of Greensboro, NC, as a memorial to her husband, the late L. Richardson.[41] “L. Richardson” was Lunsford Richardson, of Greensboro, NC, famous as the druggist who had invented and manufactured a line of pharmaceutical products, all under the brand name of “Vick’s”, in which all of the products included as their main ingredient, menthol, a new and little known drug from Japan. His best-selling and most famous product was (and still is) “Vick’s VapoRub”.[42] Richardson, who died in 1919, had been an elder in the First Presbyterian Church of Greensboro, “who took his Christian commitment seriously, always finding time to help others. Every Sunday for over twenty years he taught adult Bible classes in his church in the morning and in the Negro community in the afternoon. His special interests were the problems of the blacks, help to any who sought an education, and the benevolent causes of his church, to which he left a large portion of his Vick’s stock.”[43] It was fitting to name such a “handsome stone building” after such a generous and benevolent man. Evidence supporting Anderson’s possible (and probable) intentional effort to establish a unified and distinctive design idiom for Montreat’s growing campus (grounds), can be seen in the construction of the Richardson Foreign Missions building. Anderson himself recalls: “The building was designed by an architect of Greenville, South Carolina, to be a wooden structure, but we persuaded Mrs. Richardson to allow us to build instead, a stone building with asbestos roofing, and certain modifications were made in the original plan”.[44] This “handsome stone building” as Anderson described it, which is still standing, but now named the “Way-out Building”, shows that Anderson had made a wise decision to build using cobblestones, as not only has it stood the test of time, but it elegantly displays the decorative and attractive effect that can be achieved with the use of cobblestones. The use of rubble stone for the foundation, below the cobblestoned first floor, while attractive seems to be a portent of the eventual fate of the use of cobblestones at Montreat.

In the Spring of 1925, work began on the construction of a new Committee building and stone footbridge at the head of Lake Susan. The funds for construction were provided by the various executive “Committees” (Departments) of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian denomination, including the Committee on Christian Education and Ministerial Relief, the Committee on Home Missions, and the Committee on Religious Education and Publications.[45] The building would became known as the Lakeside Building, and functioned to house a book stone and meeting and office spaces for the above-mentioned Committees. The Lakeside building became “a very popular center during the summer season”, recalled Anderson years later. No doubt its appeal was not only because of its wraparound two-story stone-pillared verandahs which provided a cool respite from the summer sun, but also its splendid siting, overlooking Lake Susan with a then unencumbered view looking south down the Montreat valley. Of course, another aspect which may have made it popular was its accompanying stone footbridge which provided a convenient and picturesque way not only to enter the building from either side of the Lake, but it was a shorter way to get from one side of the lake to the other. Again, we see the blending of stone, with large rubble stone used for the stone verandah posts and cobblestone cladding the body of the building. The effective blending of stone is most visible on the arched entrance portico, where rubble stone is used for the posts up to the rail height on the second story verandah, where instead of using wood posts to extend to the gabled roof (as on the other verandah posts), the posts and gabled end wall is clad with cobblestone. Whether or not this blending was a result of cost-saving or intentionalin its design, makes little difference as the result is both decorative and attractive. The building has recently undergone a major renovation, resulting in the building’s name now changed to the “Katherine and Thomas Belk Center at the Left Bank”.

The accompanying connecting stone footbridge, which was built with the Lakeside Building, was built with cobblestone walls. Again, we see the decorative arts at work in the design, as originally the letters spelling out “LAKE SUSAN”, which are on the lakeside of the walkway, appears, from the old photos, to have been made using smaller light-colored cobblestones on a dark cobblestone background embedded into the cobblestone wall. Today the letters are there but appear to be made of flat light-colored stone (not cobbles), and even their text-style has been changed, nonetheless the decorative effect remains.

Even as Anderson continued to build these other buildings, behind the scenes, the re-building of the hotel for Montreat, as a “larger and better”[46] hotel, was never far from his mind. In fact, as early as the Fall of 1924, before the construction of the Lakeside building had begun, at a meeting of the Board of Trustees and Stockholders of Montreat Retreat Association (new name for the Mountain Retreat Association) was held where the Trustees and Stockholders, “representing the 17 synods of the Southern Presbyterian Church” expressed “the urgent need for the erection at the earliest possible date of a new hotel at Montreat to replace the one recently destroyed by fire”.[47] They further recommended (in a parliamentary sense) that the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees begin to “formulate plans for the new hotel and that an earnest appeal be issued to the Southern Presbyterian Church to respond liberally to the call that will be made for the necessary funds…[sic]”.[48] At an evening meeting, that same day, The Board of Directors made a resolution to empower the Executive Committee to launch a campaign to raise $200,000 to build a new hotel. They also appointed R. C. Anderson, Dr. I. J. Archer, and Mr. R. E. McGill as a special committee to secure plans and specifications for the new hotel.[49]

The special committee, under the direction of R. C. Anderson, secured the help of Asheville architect, William J. East to turn Anderson’s sketches into a working plan. Once the sketches were approved by the Board of Trustees, then East prepared the construction and engineering drawings. W. J. East had received his architectural training at the Polytechnic Institute of Pittsburg, as well as spending time at an Atelier in Germany. For the first part of his career, East practiced architecture in Pittsburg, PA, and was for many years President of the Western Pennsylvania American Institute of Architects, but in 1912, at the age of 47, East moved his family and his practice to Asheville, NC, where he remained the rest of his life. Although W. J. East advertised that “Designing of Apartment Houses and Churches, A Specialty”[50], I suspect that the reason Anderson chose East, was that he was sympathetic to the work of the church and was willing to be give Montreat a discount on his charges. Anderson later recalled that Mr. East “was employed at half of his usual charges”[51]-quite a discount indeed!

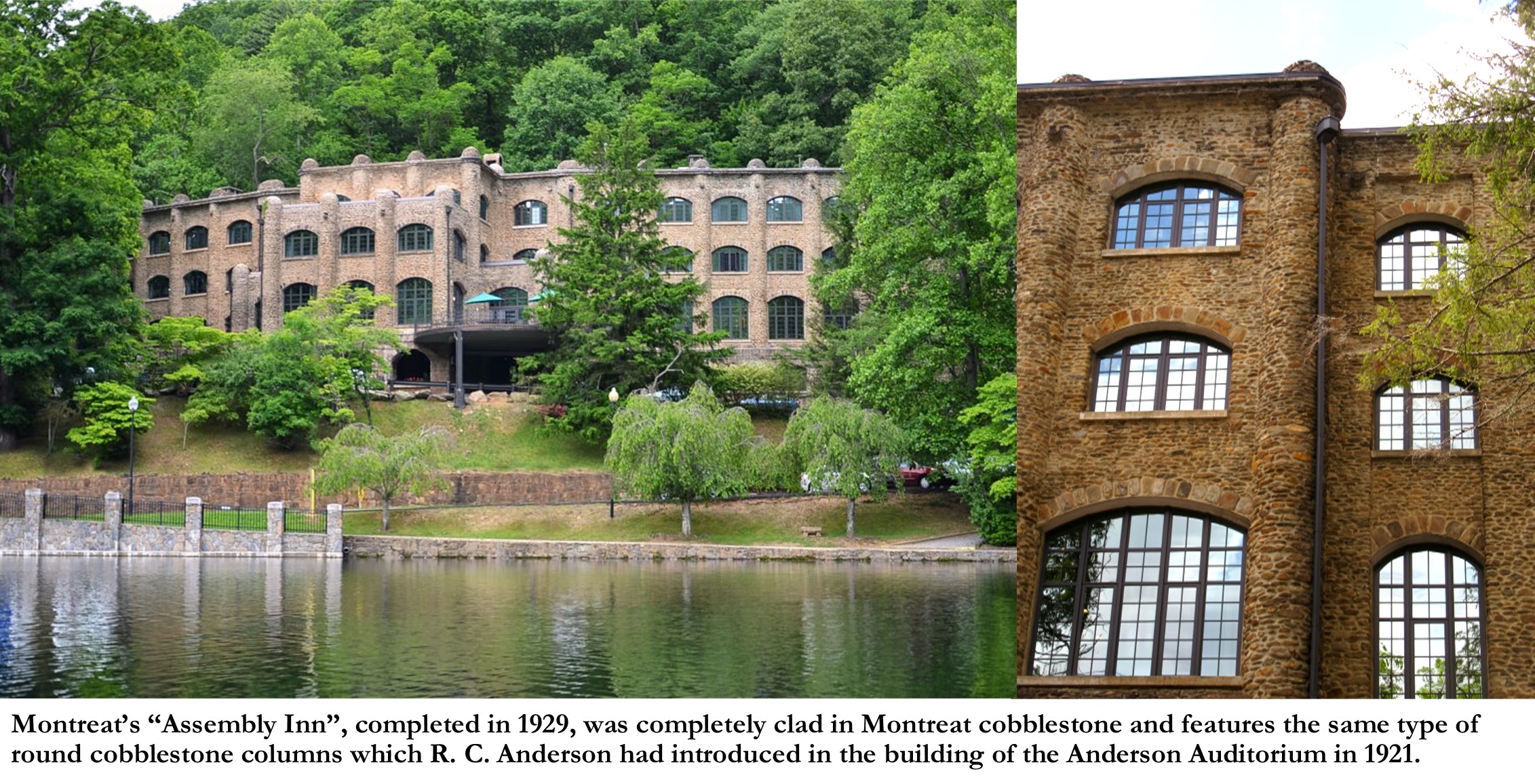

Building the new hotel, which shortly was named, Assembly Inn, was a larger undertaking than even building the auditorium, primarily due to its size and location on the side of the mountain. Rev. Anderson gives us a good description the proposed building:

“It was built of Montreat stone cobblestone with large columns rising from the base to the top of the roof [four stories]. The lower and upper lobbies and the dining room were to be finished on the interior with scrap marble floors giving a mosaic effect, with mica-flint rock, quartz, cyanite, and other beautiful stone in the interior giving a warm, colorful, and pleasing effect within, all partitions between rooms to be built of hollow tile with no wood, excepting the doors, to be used in any portion of the building. The cost of the building was approximately $225,000. The furnishings and heating system cost approximately $75, 000.

Due to the size of the project, as well as difficulties in fund-raising, the actual construction was delayed until February of 1926. Again, with R. C. Anderson acting as contractor, Mr. Charley Godfrey and his laborers were first hired to do the construction, but the project took so long that Herman Holdway was hired in place of Mr. Godfrey to finish the construction. The construction was so monumental that it required an “immense” amount of concrete and stone, as Anderson later records, “About fifty-five carloads of cement were used and stone without limit”[52] The cobblestone was especially troublesome, as the amount needed to clad the exterior was so great that soon “all the cobblestones in the grounds [onsite] seemed to be exhausted”.[53] But wisely Anderson solved the problem quickly, as he later recalled: “the valves in the dam forming the lake were opened and the water rushed down the stream for a mile to the lower boundary of the grounds, and the rushing current of the water washed up as much of the cobblestone as we had in the beginning. This process was repeated whenever the supply of the cobblestone was exhausted”.[54] Two railway carloads of marble pieces were donated by two separate yards in Knoxville, TN, with Montreat only having to pay for shipping. Construction of the Assembly Inn took just over three years, and on May 15, 1929 the Inn was officially opened to a full house.

Although not specifically stated by Rev. Anderson, except for his admittance to their having to repeatedly open the dam to forcibly supply the needed cobblestone to complete the Inn, it must have become apparent to Anderson that the supply of onsite cobblestones was not endless, as although Anderson continued to build more buildings at Montreat into the 1930’s & 1940’s, until his retirement in 1947, the Assembly Inn was the last building to use cobblestones solely for its exterior cladding. In fact, only one more building would be built by Anderson after the Assembly Inn which would utilize cobblestones in its construction, and even that building additionally used the flat rubble stones (like used on the interior of the Inn) for large wall areas between round cobblestone columns.

On December 28, 1945, a fire quickly consumed the old wood-framed Alba Hotel at Montreat. Although Rev. R. C. Anderson had offered his resignation three years earlier as President of the Mountain Retreat Association in order to spend more of his time developing and growing the fledgling Montreat College, because of his experience and successes in managing building projects, he was asked to manage one final project for Montreat. In his standard modus operendi, Anderson quickly made some sketches for rebuilding the Alba Hotel. He gave his sketches to Mr. William Green, a contractor in Black Mountain, to turn them into scalable architectural plans, which Mr. Green generously prepared for a modest $50 fee.[55] Anderson then with plans in hand went to ask his good friend Herman Holdway, who had previously superintended many of the previous stone Montreat buildings, if Holdway could gather his former crew and take on one more project. Although Holdway was then employed fulltime with a local manufacturing firm, he agreed to take on the project, and despite his former crew having all gotten other fulltime jobs, he was able to convince them to join his team for this last project.[56]

Construction began on the new hotel in the summer of 1946. A July 1946 newspaper report gave a good description of the layout of the yet unnamed hotel then being built on the site of the former Alba Hotel:

It will stand on the same location: it will face Lake Susan, the huge main dining room will be glassed to a large extent, but its real feature will be that this portion of the building will be one story and beyond it, Gaither Hall will be visible from Assembly Inn. On each end of the new building two three-story wings will be erected containing 70 rooms each. In front will be a massive stone portico and an open stone and concrete terrace. Between the portico columns and the terrace will be a wide driveway. Stone and concrete steps will lead down to the main roadway in front.

Two lobbies are planned for the building, one in the front end of the first floor of each wing. The main dining room, 90 by 75 feet, will seat approximately 700 persons. In addition, a smaller dining room will be built on each end of the main room into each wing- to accommodate smaller groups, but large enough to seat 100 or more people each.

The bedroom wings will have large hallways running the length of each floor. There will be rooms with private baths, and rooms with connecting bath and each room is to have a large closet. The rooms will be amply large to contain either a double bed, or twin beds and the other necessary, but minimum hotel room furniture. While the new building is to serve as a summer hotel for conference guests of the general assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States, during the fall and winter, when college is in session, the building will serve as a dormitory for students of Montreat college.[57]

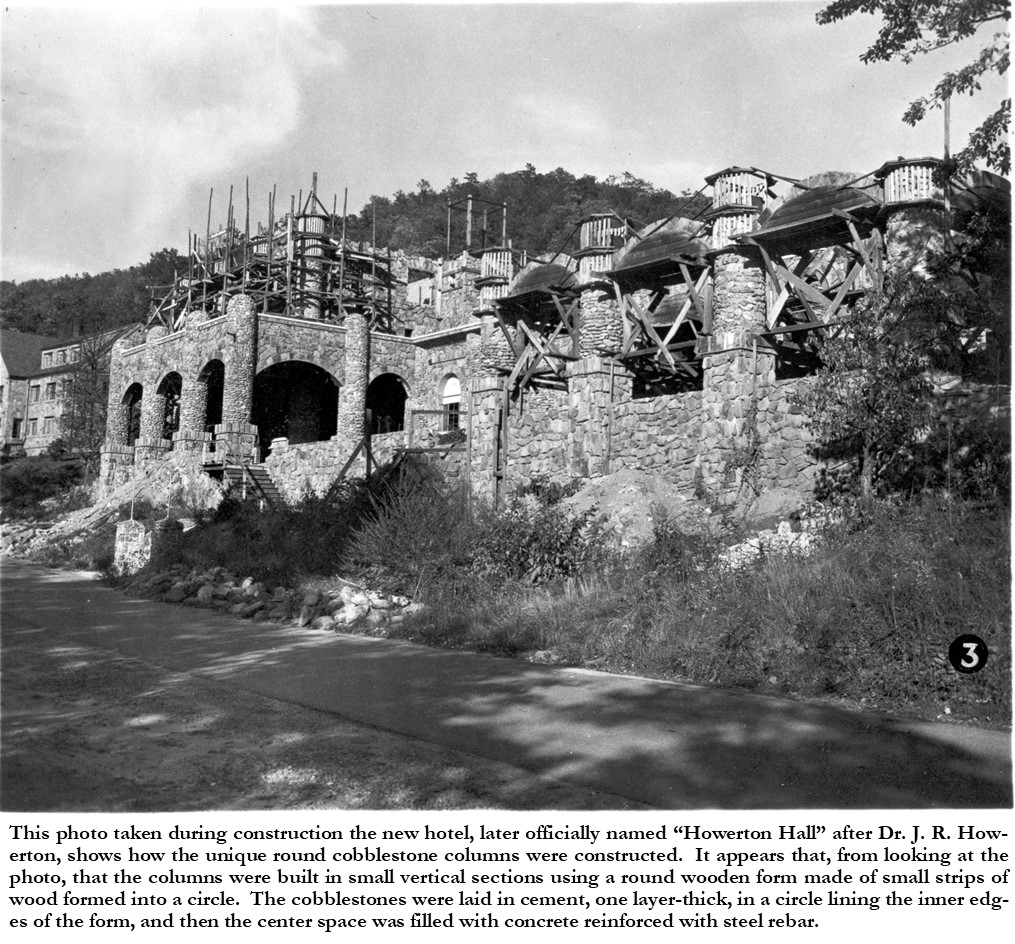

A photo taken during construction the new hotel, later officially named “Howerton Hall” after Dr. J. R. Howerton who was the former President of Montreat who in 1907 was responsible for building the Alba Hotel, shows how the unique round cobblestone columns were constructed. It appears that, from looking at the photo, that the columns were built in small vertical sections using a round wooden form made of small strips of wood formed into a circle, much like building a barrel, except that every other stave was omitted. The cobblestones were laid in cement, one layer-thick, in a circle lining the inner edges of the form, and then the center space was filled with concrete reinforced with steel rebar. This process was continued vertically on each column by moving the forms to sit on each completed section. It also appears from the photo that two or three sections of forms were stacked on each other at a time. After each vertical column sections were completed, before moving the forms up, the exterior walls in between the columns were infilled with flat rubble stone laid against hollow clay tile. In some of the major spaces such as the lobbies and dining room, the clay tile walls were also faced on the interior with rubble stone. Again, Anderson used broken marble pieces for the interior floors on the concrete slab floors. Not only was the marble durable, and the effect was attractive, but it was also cost effective as Anderson would solicit donation of the marble from various sympathetic quarries or suppliers.

As construction of the new hotel lagged on into 1947, Rev. R. C. Anderson, who was now 83 years old, resigned from any connection with the building of the new hotel. Dr. J. Rupert McGregor, who had already been appointed as Anderson’s successor as President of Montreat, then took over the project. Fraught with fund-raising difficulties and the urgencies of other needed projects, the new hotel, Howerton Hall was not “completed” and opened until 1950. However, the building was neither ever used as a hotel, nor was it ever totally completed, as only one of the three-story wings at each end was completed, with the wing on the south only finished to one-story. Despite having never been fully completed, Howerton Hall has been and continues to be a vital part of the Montreat campus.

One other quasi-institutional building that was built at Montreat using river-rock was the William Black Home, built in the late 1940’s. In 1916, C. E. Graham sold his Montreat home on the Upper Terrace (now addressed as 329 North Carolina Terrace) to the North Carolina Synod of the Presbyterian Church to be renovated and used to house low-salaried ministers and Christian workers and their families of the North Carolina Presbyterian Church, to provide affordable lodging when they would attend the summer conferences. In 1928, the name of the ministers home was changed to the “William Black Memorial Home for Religious Workers of the Synod of North Carolina”, in honor of Dr. William Black from Charlotte, NC who for 30 years, had been a noted evangelist with the North Carolina Synod.[58] In June of 1946, at the start of the summer conference season, with reservations booked at the William Black Home, a devastating fire broke out which destroyed the wood-frame structure.[59] Immediately after the fire, using the insurance money as seed money, the North Carolina Synod began a campaign to rebuild the home. This fire was just on the heels of the devastating fire of December of 1945, just six months earlier, which destroyed the wood-frame Alba Hotel at Montreat.

It took over three years to raise the necessary funds to begin construction of the new home. In the Spring of 1949, it was officially announced that the North Carolina Synod was going to build a new William Black Home.[60] Like the new Alba Hotel (Howerton Hall), then being built at Montreat, the plans for the new William Black Home called for the use of fire-resistant materials: concrete block, steel, concrete, and native stone. The plans which were made from sketches prepared by “Rev. O. V. Caudill, of Salisbury [NC], synod’s building consultant”[61], called for the exterior to be completely clad in river-rock, to blend with the other institutional buildings of Montreat. One difference of the stone masonry on the William Black Home, in comparison to the earlier stone buildings of Montreat, is that instead of using all cobblestones, or a combination of cobblestones and rubble field stone, the Black home used all river-rock, but not all cobblestones. The cobblestones were laid in a random pattern interlaced with larger river-rock laid up vertically. This was a “modern” or new way to lay up of river-rock on houses and buildings, and all the later examples at Montreat used this new coursing method, gone were the days where only cobblestones were used in building river-rock walls. This use of multi-sized river-rock remains to this day. Construction of the new William Black Home finally began in 1950 and it was completed and opened by June 1951.

Few cottages were built at Montreat using only cobblestones, and even on those that used cobblestones, the cobblestones were used only for foundations, porch columns, porch stair walls, and other landscape walls and features. One of the few cottages that used cobblestones, started as a cottage but then became an institutional building of the Montreat College. In 1946, friends of Mr. & Mrs. Crosby Adams began to solicit and campaign for a “shrine” to these talented and nationally known musicians who had made their home at Montreat since 1913. An appropriate “shrine” was proposed to be a new building at Montreat College that would be named the “Crosby Adams Music Building”, in honor of the couple, who were still living, though in their nineties. Prompted by an appeal by Virginia Le Vay Morrison in the March 1946 edition of the Christian Observer, music clubs, institutions, and friends of the Crosbys began to send donations for the new building to Montreat. Two years later, on December 16, 1948, in a special chapel service at Montreat College, Dr. J. Rupert McGregor, president of the college and the Montreat Association, made the official announcement of the purchase of a building from Mrs. Frank Wilson, for the new “Crosby Adams Fine Arts Building”. At the Chapel program, attended by Mr. and Mrs. Crosby Adams and the students of Montreat College, Dr. McGregor presented the key to the building to Mrs. Adams and, following the chapel program, the crowd watched as Mrs. Adams officially opened the building.[62]

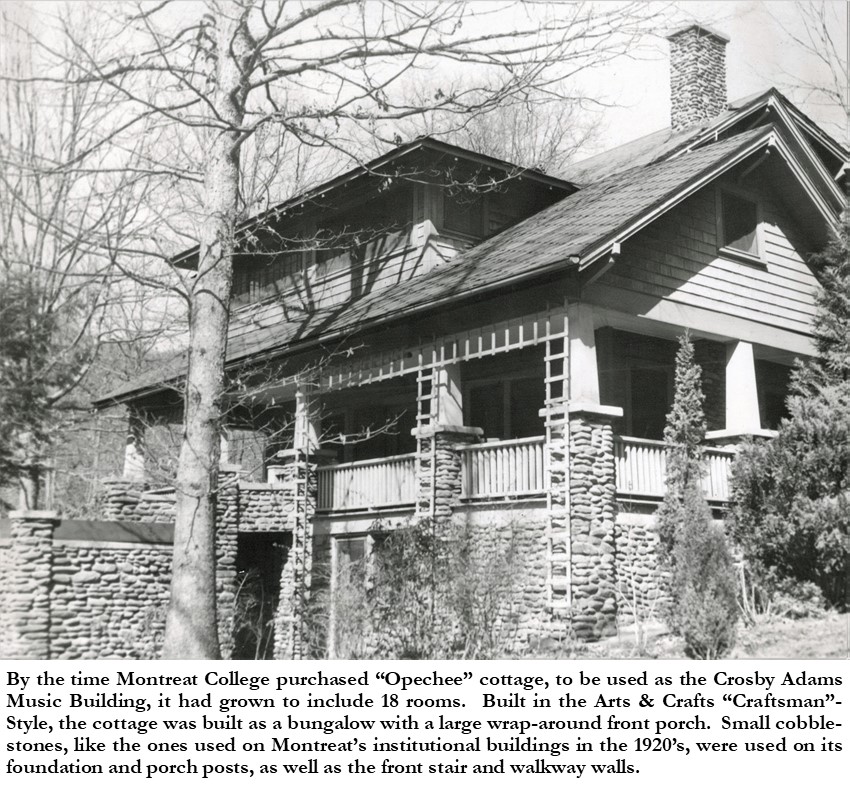

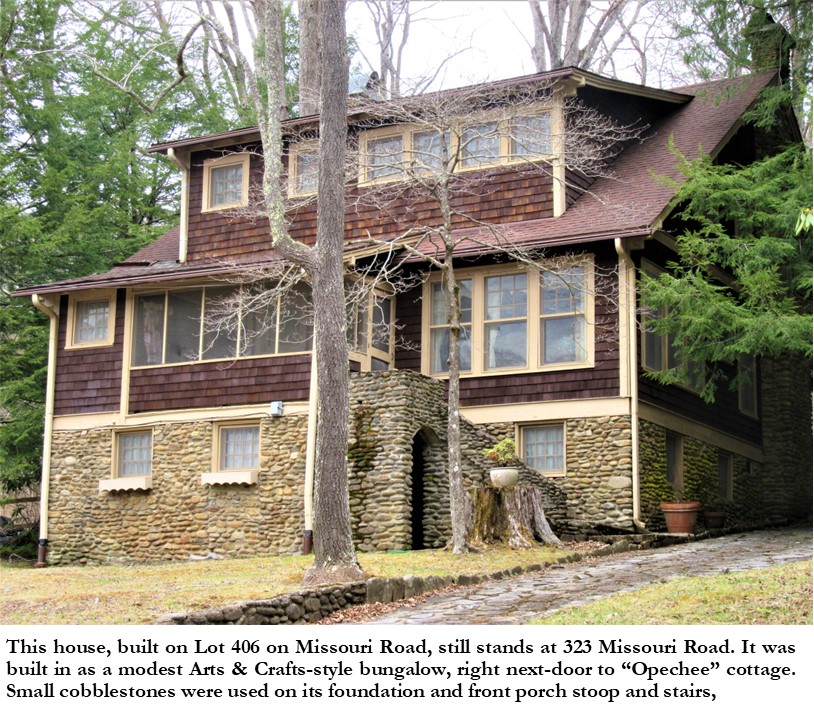

The building that became the Crosby Adams Fine Arts Building was “Opechee” cottage on Lot 404 on the northside of Missouri Road, which for many years was the home of Julia Stockard Wilson. The cottage/ or more likely just the lot, was purchased in December of 1923 by Julia’s mother-in-law, Mrs. Elizabeth Caldwell Wilson. Julia Wilson had inherited the home following the December 1925 passing of her mother-in-law. Julia and her husband had been living in the cottage with Mrs. E. C. Wilson, but unfortunately Julia’s husband, Frank Leroy Wilson, Sr. had also passed away (in the cottage at Montreat) in May of 1925, just months before the passing of his mother. Julia continued to live at “Opechee” cottage until selling it in 1949 to Montreat College. By the time Montreat College purchased the cottage, it had grown to include 18 rooms. Built in the Arts & Crafts “Craftsman”-Style, the cottage was built as a bungalow with a large wrap-around front porch. Small cobblestones, like the ones used on Montreat’s institutional buildings in the 1920’s, were used on its foundation and porch posts, as well as the front stair and walkway walls.

Interestingly, the same small cobblestones that were used on “Opechee” cottage, were also used on the foundation and front porch stoop and stairs, right next-door on the cottage built on Lot 406 on Missouri Road. This house, which still stands at 323 Missouri Road also, though more modest, is an Arts & Crafts-style bungalow. It was purchased by, and I believe built by, William Wilson Glenn and his wife, Mary Love Glenn in November of 1923. Although William Wilson Glenn was not a close relative of his neighbor, Mrs. Elisabeth C. Wilson, both, and their families were members of First Presbyterian Church of Gastonia, whose former pastor was Dr. Robert C. Anderson.

Another example of a Montreat cottage that used cobblestones, was a cottage built in 1923 for Rev. William P. Chedester at 155 Virginia Road. “Mr. & Mrs. William Chedester are erecting a new home which they expect to occupy by the first of May”, reported the April 19, 1923 edition of the Asheville Citizen-Times.[63] The correspondent further reported that the Chedester’s new home was “a bungalow type with foundation of river rock.”[64] More specifically, the Chedester home was built as a front-gabled wood-frame bungalow on a raised basement foundation made of small cobblestones. The cobblestones were also used on the porch posts piers which rise to the height of the front-porch rails, as well as for the home’s stone fireplace and chimney. Rev. Chedester was the pastor of Ora Street Presbyterian Church in Asheville, NC. The Chedesters retired to their Montreat cottage in 1940’s, where in 1947 Mrs. Chedester passed away. A few months later Rev. William P. Chedester sold Montreat cottage and moved back to Asheville.

One final example of a Montreat cottage which used cobblestones was a cottage, nearby the Chedester cottage, at 203 Virginia Road, built in 1923 for Katherine Allen Hadley. Katherine Allen Hadley was the widow of J. Livingston Hadley of Nashville, TN, who had died in 1918.[65] Katherine moved into her new cottage with her “nieces”, Miss Annie Hadley, and Miss Katherine E. Hadley, who although technically her nieces, were also her stepchildren. Katherine Allen Hadley, following the death of her sister Annie Allen Hadley in 1908, had married her brother-in-law J. Livingston Hadley and took over the care of her sister’s children. The Hadley cottage at Montreat was not only built the same year as the Chedester cottage, but it too was a wood-frame bungalow (although with side gables) built on a cobblestone raised basement foundation. Cobblestones were also used on the Hadley cottage porch post piers as well as for its fireplace and chimney. The Hadley cottage, upon the death of Katherine Allen Hadley, was inherited by her nieces, Annie and Katherine E. Hadley, who both at the time were “institutionalized” at the Morganton State Hospital-then a place where those suffering with mental illnesses were sent. Both nieces eventually were released from the hospital and occupied the Montreat cottage for several years. Katherine E. Hadley later married a troublesome husband named Mr. Kelley, and unfortunately the cottage became infamous for the many loud domestic disturbances emanating from its windows. But more happily, the cottage was famous for the beautiful piano music that resonated from within, through the hands of a masterful pianist, Mrs. Katherine E. Hadley Kelley. Both Katherine and her sister Annie had been trained in music by Mrs. Crosby Adams, the resident and nationally acclaimed music teacher of Montreat. Upon the death of Mrs. Kelley, the cottage was inherited by her cousin, Miss Annie Belle Hill, whose mother was the sister of Mrs. Kelley’s mother and stepmother. Miss Hill had been living in the cottage for years with the Hadley sisters, while she held the position, as the director of the Presbyterian Heritage Center, which is located at Montreat. Annie Hill finally sold the cottage out of the family in 1970.[66]

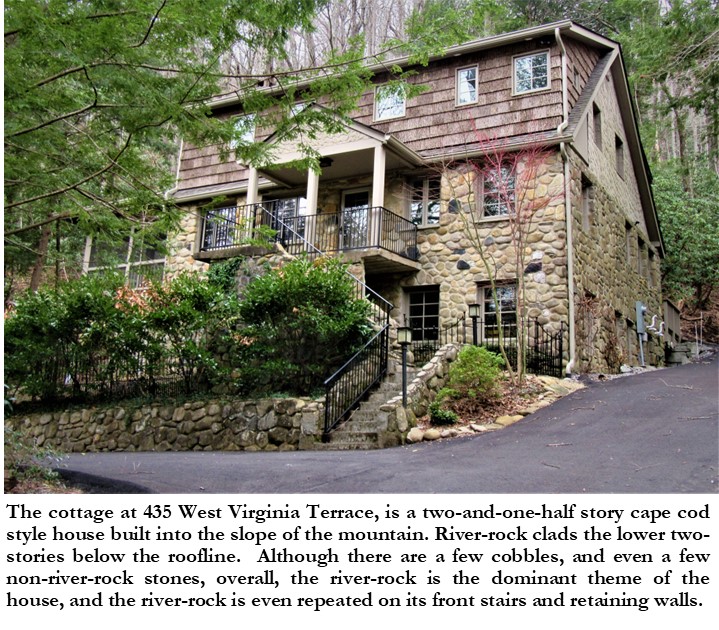

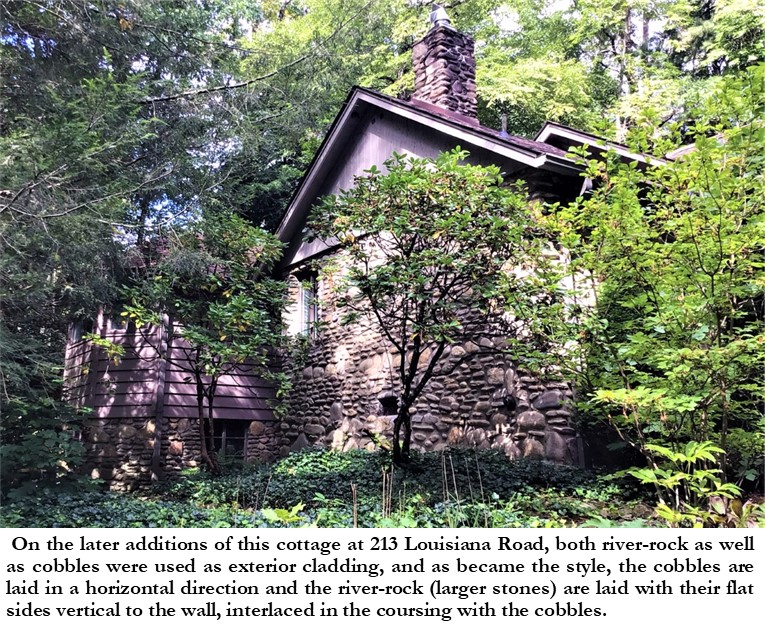

Let me just clarify that for this article I call the small oval shaped river-rock, cobbles or cobblestones and the larger flat (though rounded) stones as river-rock, although technically some those large stones, if less than 10”, are classified as cobbles, and are technically just large cobbles. That being said, the use of cobblestone (small cobbles) on cottages at Montreat seemed to be a phenomenon of the 1920’s and 1930’s, however the use of river-rock (small cobbles, large cobbles and even boulders) on cottages never quite died out. Two examples, to illustrate this point are: the 1940’s cottage at 435 West Virginia Terrace, and the more recent additions made to the cottage at 213 Louisiana Road. The cottage at 435 West Virginia Terrace, is a two-and-one-half story cape cod style house built into the slope of the mountain. River-rock clads the lower two-stories below the roofline. Although there are a few cobbles, and even a few non-river-rock stones, overall, the river-rock is the dominant theme of the house, and the river-rock is even repeated on its front stairs and retaining walls. On the later additions of the cottage at 213 Louisiana Road, both river-rock as well as cobbles were used as exterior cladding, and as became the style, the cobbles are laid in a horizontal direction and the river-rock (larger stones) are laid with their flat sides vertical to the wall, interlaced in the coursing with the cobbles. This seems to be a more contemporary way of using, laying, and coursing of river-rock today.

The river-rock/cobblestone design idiom introduced in 1921 by Rev. R. C. Anderson, not only impacted the design of campus buildings and cottages at Montreat, but perhaps even more noticeably it also impacted Montreat’s landscape design. Montreat’s geographic condition, occupying the valley and slopes of a natural “cove” necessitated (and still necessitates) much terracing and many retaining walls in the building its roads, buildings, cottages, lake, and outdoor gathering spaces. We have already looked at examples of the use of cobblestone (and other river rock) for the retaining wall surrounding Lake Susan (and the dam), and for the building of bridges at Montreat, however, let’s look at some examples of other types of landscape features of Montreat that used river-rock/cobblestone.

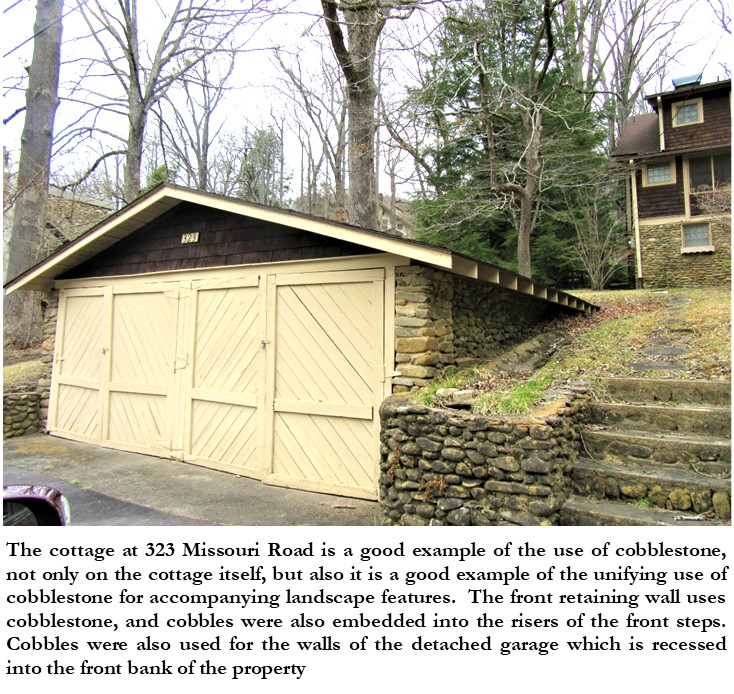

Perhaps river-rock and cobblestone’s most profuse use at Montreat, besides their use on the institutional buildings, was and is their use on outdoor walls, most specifically on retaining walls. Their use on retaining walls followed the same timeline and trend as their uses on Montreat’s buildings and cottages, with the earlier walls (1920’s-30’s) using cobblestone, the later walls using larger river-rock or fieldstone. There are many examples around Montreat of the earlier cobblestone walls-let’s look at just a few examples. A favorite of mine is a section of retaining wall that was built at the back of the dam, separating the eastern shoulder of Assembly Drive from the steep embankment dropping down to the creek bed below the dam. The wall was built using river-rock, both small and large cobbles, all laid in a horizontal coursing. Two unique features of the wall are, its gracefully curved sweep up to meet the wall of the new dam and walkway, and the treatment of the top of the wall. Instead of using capstones to cover the gap formed between the inner and outer layers of the wall, to protect the wall from water penetration, in the early days of Montreat, they covered the tops of the walls with a layer of concrete or mortar, in which they then embedded small, pointed pieces of rock in a random pattern. This not only gave a decorative ornament to the top of the wall, but I suspect it also deterred people from sitting or walking on the walls. This unique top of the wall treatment was used at Montreat on river-rock and non-river-rock stone walls, so that it became its own design idiom (tradition). Lots of retaining walls surrounding cottages and their yards also used cobblestone and/or river-rock for their construction. The cottage at 323 Missouri Road is a good example of the use of cobblestone, not only on the cottage itself (as mentioned above) but also a good example of the unifying use of cobblestone for its accompanying landscape features. The front retaining wall uses cobblestone, but cobbles were also used for the walls of the detached garage which is recessed into the front bank of the property. This type of garage, built into the bank between two sides of a low retaining wall, was common in Montreat, because most of the cottages were built into the hillsides and were only accessible from the front (downhill) side of their properties. Often retaining walls along the roads (streets) were also recessed into the front banks of properties to provide for off-street parallel parking of vehicles.

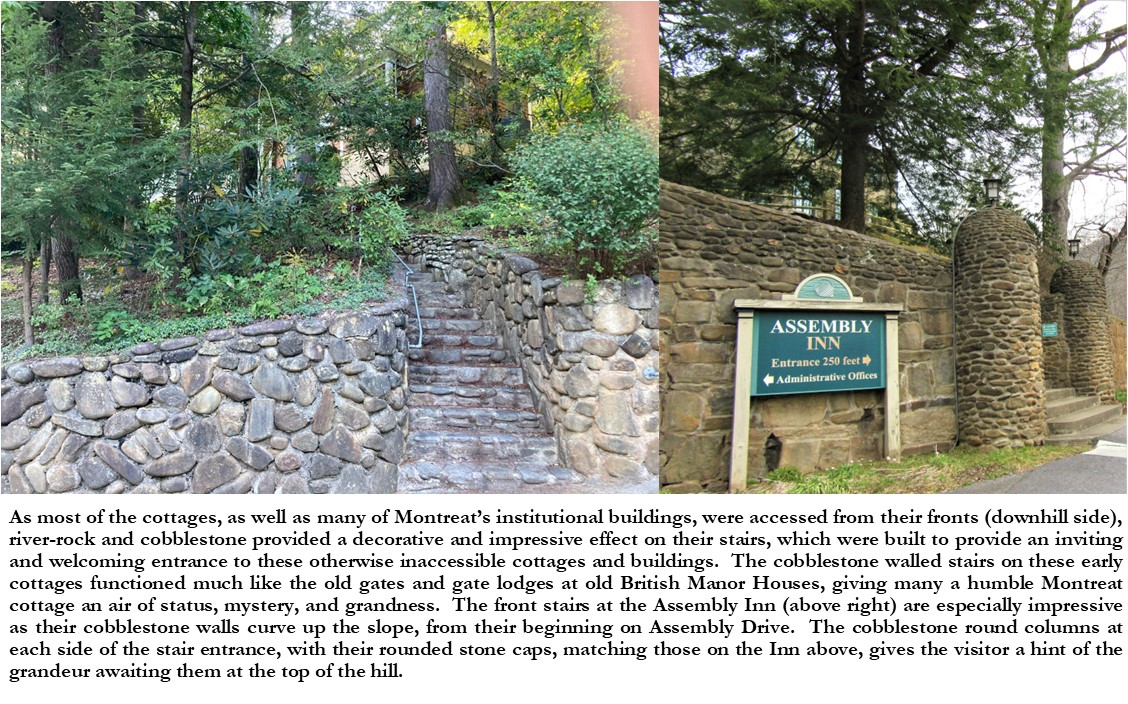

As also evidenced at 323 Missouri Road, one of the most effective uses of river-rock and cobblestone at Montreat were on outdoor stair walls and stairs. As most of the cottages, as well as many of Montreat’s institutional buildings, were accessed from their fronts (downhill side), river-rock and cobblestone provided a decorative and impressive effect on these stairs, which were built to provide an inviting and welcoming entrance to these otherwise inaccessible cottages and buildings. At 323 Missouri Road cobbles were also embedded into the risers of the front steps.

The cobblestone walled stairs on these early cottages especially, functioned much like the old gates and gate lodges at old British Manor Houses, giving many a humble Montreat cottage an air of status, mystery, and grandness. The front stairs at the Assembly Lodge are especially impressive as their cobblestone walls curve up the slope, from their beginning on Assembly Drive. The cobblestone round columns at each side of the stair entrance, with their rounded stone caps, matching those on the Inn above, gives the visitor a hint of the grandeur awaiting them at the top of the hill.

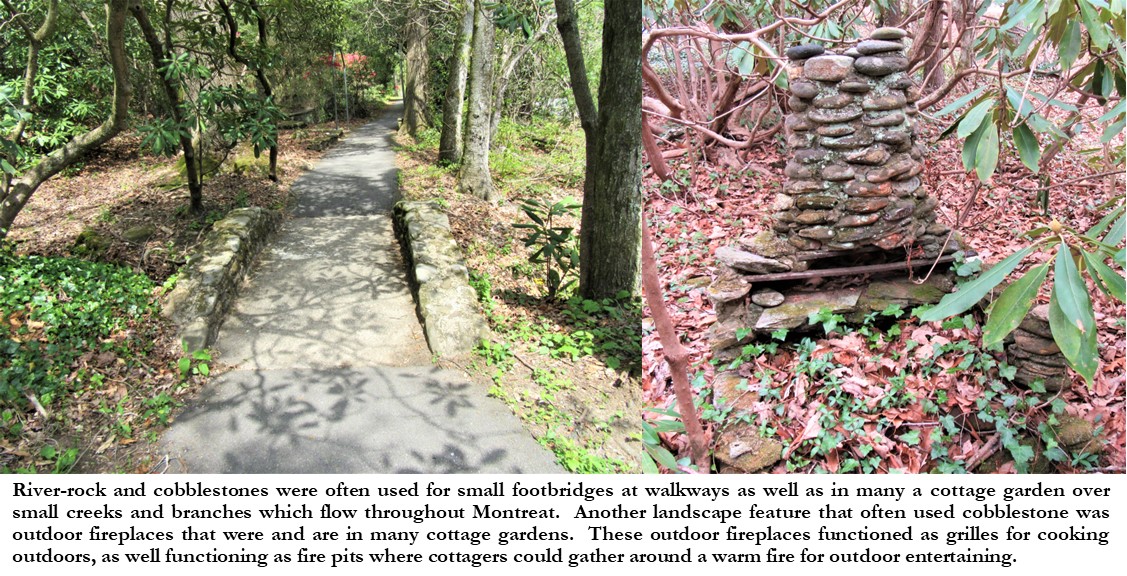

River-rock and cobblestones were often used for small footbridges at walkways as well as in many a cottage garden over small creeks and branches which flow throughout Montreat. Another landscape feature that often-used cobblestone was the outdoor fireplaces that were and are in many cottage gardens. These outdoor fireplaces functioned as grilles for cooking outdoors, as well functioning as fire pits where cottagers could gather around a warm fire for outdoor entertaining.

An unusual, and noted landscape feature of Montreat, which was constructed using river-rock, including mostly cobblestone, is the “Wynne-Lithia Spring”. In 1908, J. S. Wynne, then Mayor of Raleigh, NC, and his wife Lula Wynne built a large two-story, eight room house, which they named “Woodland Heights”, on lots 287 and 288, just above North Carolina Terrace.[67] “Just below his home Mr. Wynne built in 1910 Wynne Spring”, recalled his daughter, Mrs. C. A. Dillion in 1945, “from which fine lithia-water flows.”[68] In 1888, Lithia Springs, Georgia opened as a health resort where people would come to drink and bathe in the Lithia Spring, and soon thereafter, “bottling of the water began for commercial sale. To this day Lithia Spring Water is still bottled and sold for its high lithium and mineral content as a general health tonic”.[69] As Lithia Springs are rare, when J. S. Wynne found that he had one on his property, he decided to share it with the whole of the Montreat community. Where the spring actually came out on his property is unknown, however we know that he piped it down to the edge of North Carolina Terrace, where is built a retaining wall and cobblestone recessed grotto on the side of the road, where anyone could come and drink or fill their jugs with fresh lithia-spring water. In 1944, Wynne’s daughter, Mrs. C. A. Dillon constructed stone benches on each side of the grotto, “for the convenience of people coming to Montreat for a picnic lunch”.[70] I suspect that may have also been when the engraved stone, “WYNNE-LITHIA”, was erected at the top of the grotto. The cobblestone on the grotto appears to be smaller and more weathered than the flanking stone benches, indicating that the grotto was original to the opening of the spring in 1910. If so, that would be the only case that I have found in Montreat where the use of cobblestone/river-rock would have predated the 1921 building of the Anderson Auditorium.

The recently built Montreat Town Hall pays homage to Montreat’s historic built environment, specifically its use of river-rock and cobblestone. This indicates that the river-rock/cobblestone design idiom of Montreat has not totally died away or has not been totally forgotten.

Montreat–the town, college, and conference center, share the heritage of a unique and distinctive design idiom of using river-rock, cobblestone, and native stone, which was started in 1921, under the suggestion and leadership of Rev. Robert C. Anderson. And although the use of cobblestone and river rock at Montreat is no longer in its heyday, much of it remains at Montreat, and that which does remain should be preserved as a unique design idiom which has given Montreat its distinctive and cherished built environment–its je ne sais quoi that IS Montreat!

Photo & Image Credits: (Note: All cropping and captions by author)

Montreat postcard- Collection of Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

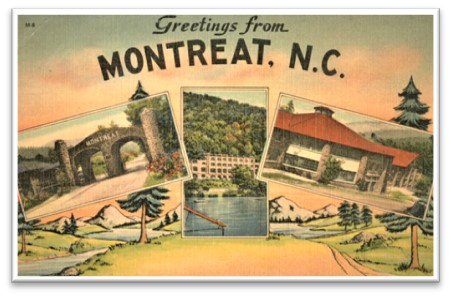

Old Montreat Gate postcard- Image # C110-5, Contact print of a Pelton photo of the entrance of Montreat, NC. In the foreground is the dirt road. In the center background is an archway with a sign, “Montreat Registration Office”. Copyright 1910.- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Dedication of Monument of Founding of Montreat-1909, photo courtesy of the Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC.

1922-Anderson Auditorium-Officials & Building Crew– Image # C170-8, Pelton photo (A7419) of Montreat officials and building crew in front of the recently completed Anderson, 1922- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Color Photo of Creek– photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

2016 Geological Map Excerpt– 2016. Bedrock Geologic Map of the Montreat 7.5-minute Quadrangle.- GeoPDF Download – NC DEQ- https://deq.nc.gov › ncgs-ofr-2016-06-montreat

James Tinker Cobblestone House– Oblique view of the National Register-listed James Tinker House, built between 1828 and 1830 in Henrietta, Monroe County, New York, By Christopher L. Riley, 2022.-Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. -https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:James_Tinker_House_%E2%80%94_Henrietta,_Monroe_County,_New_York.jpg

California Bungalow– This California bungalow was illustrated in the Craftsman Magazine in Nov. 1907 as an example of cobblestone architecture and reprinted in Gustav Stickley, Craftsman Houses (2nd edition, 1909

Montreat Stone Gate & Gate Lodge postcard– Collection of Mary McPhail Standaert & Joseph Standaert, used with permission.

Montreat cobblestone bridge postcard– Collection of Mary McPhail Standaert & Joseph Standaert, used with permission.

B & W Photo of Cobblestone Bridge– photo courtesy of the Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC.

1940 Photo of Montreat Dam- photo courtesy of the Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat, PO Box 207, Montreat, NC.

Richardson Foreign Missions Building postcard– Collection of Mary McPhail Standaert & Joseph Standaert, used with permission.

Lakeside Building-Front View postcard– Collection of Mary McPhail Standaert & Joseph Standaert, used with permission.

Lakeside Building & Footbridge- photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

Colored Photo of Assembly Inn– https://montreat.org/accommodations

Colored photo of closeup of Assembly Inn Wall and Column– photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

Photo of Construction of Howerton Hall– Image # C115-8- Southwest view of the “new” Alba Hotel (1948) under construction.- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Photo of William Black Home Burning– “North Carolina Home Damaged in Montreat Fire”, Asheville Citizen-Times, June 22, 1946, page 6. -newspapers.com

William Black Home– photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

B & W Photo- Crosby Adams Music Center– Digital Archive-“Montreat College Buildings”, Montreat College, Montreat, NC- https://www.montreat.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Crosby_Adams_Fine_Arts_Building_and_Music_Studios.jpg

323 Missouri Road Cottage– photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

Chedester Cottage-155 Virginia Terrace– photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

Hadley Cottage- 203 Virginia Road- photo by Nancy Thomas Wofford, Greenville, SC & Montreat, NC., Note inset photo of Katherine Allen, used with permission from Deborah Kennedy via ancestry.com.

435 West Virginia Terrace Cottage– photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

Addition at 213 Louisiana Road– photo by Nancy Thomas Wofford, Greenville, SC & Montreat, NC.

Photo of Section of Retaining Wall-Assembly Drive- photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

Garage and Retaining Wall & Stair at 323 Missouri Road- photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

Stone Stair to Cottage– photo by Nancy Thomas Wofford, Greenville, SC & Montreat, NC.

Assembly Inn Stair at Assembly Drive– photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

Photo of Stone Footbridge at Assembly Drive- photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

Photo of Outdoor Fireplace– photo by Dale Wayne Slusser, Asheville, NC.

Photo of Wynne-Lithia Spring– photo by Nancy Thomas Wofford, Greenville, SC & Montreat, NC.

Photo of Montreat Town Hall– photo by Sineath Construction, 65 Monticello Road, Weaverville, NC- on website at: https://sineathconstruction.com/portfolio/commercial/new-town-hall/

[1] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, by Robert Campbell Anderson, D. D. (Montreat, NC: Rev. Robert C. Anderson, Printing by Kingsport Press, Inc, Kingsport, TN), 1949, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 1.

[2] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, by Robert Campbell Anderson, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 3.

[3] The Story of Montreat, From Its Begining 1897-1947, by Robert Campbell Anderson, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, pages 3-4.

[4] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, by Robert Campbell Anderson, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 11.

[5] Ibid.

[6] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, by Robert Campbell Anderson, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 15. See Also the 1897 Odell survey: 09/07/1898 Plat of Montreat, Deed bk. 106, page 520.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds. And 1906 Lockwood & Green Survey Plat: 01/01/1906 Plat of Montreat, Deed bk. 154, pages 1-3.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds

[7] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, by Robert Campbell Anderson, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 15.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, by Robert Campbell Anderson, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 16.

[10] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, by Robert Campbell Anderson, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 18.

[11] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, by Robert Campbell Anderson, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 21.

[12] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, by Robert Campbell Anderson, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 77.

[13] “More leaders are scrapping the 40-hour workweek. Here’s how it became so popular in the first place.”, by Marguerite Ward and Shana Lebowitz, 2022, from the Business Insider, online magazine. https://www.businessinsider.com/history-of-the-40-hour-workweek-2015-10

[14] Ibid.

[15] The Log Cabin: An American Icon, by Alison K. Hoagland. (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2018), page 148.

[16] “MONTREAT AUDITORIUM COSTING ABOUT $10,000 IS NEARING COMPLETION”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 11, 1921, page 16.-newspapers.com.

[17] Ibid.

[18] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 80.

[19] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 78.

[20] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 79.

[21] “Many Gaston People Now at Montreat: Assembly Grounds A Very Popular Place This Summer—Correspondent Finds Many Things of Interest”, Gastonia Gazette, July 26, 1922, page 1.- newspapers.com

[22] Ibid.

[23] Info from geologist, Criss Capps-from email correspondence to Dale Slusser. “On Wed, Sep 7, 2022 at 11:09 PM Criss Capps crisscapps@gmail.com“. Also from: Bedrock Geologic Map of the Montreat 7.5-minute Quadrangle, Buncombe, McDowell, and Yancey Counties, North Carolina, by Bart L. Cattanach, G. Nicholas Bozdog, Sierra J. Isard, and Richard M. Wooten, 2016. – https://digital.ncdcr.gov/documents/detail/3691219

[24] https://www.dictionary.com/browse/folk-art

[25] Cobblestone Quest: Road Tours of New York’s Historic Buildings, by Rich & Sue Freeman. (Englewood, FL: Footprint Press, 2005), page 10.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “Cobble Stone Building”, by E. G. W. Dietrich, “The Architect, Builder and Woodworker, Volume 23”, (New York: C.D. Lakey, April 1887), page 52.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] “The Effective Use of Cobblestones as A Link Between House and Landscape”, The Craftsman, 1908. This article was republished in Craftsman Homes: Architecture and Furnishings of the American Arts and Crafts Movement, by Gustav Stickley. (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1979), pages 102-108.

[32] “The Effective Use of Cobblestones as A Link Between House and Landscape”, in Craftsman Homes: Architecture and Furnishings of the American Arts and Crafts Movement, page 102.

[33] Ibid.

[34] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 81.

[35] “Wealthy Textile Man Dies After Apoplexy Attack”, reported from Asheville through the Associated Press, Fayetteville Observer, Fayetteville, NC, August 24, 1922, page 1. -newspapers.com

[36] “The history of Greenville’s Camperdown Mill” by Eric Connor, Greenville News, online, 2015-2016.- https://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/news/local/greenville/downtown/2015/02/14/history-greenvilles-camperdown-mill/23409423/

[37] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 81.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Montreat, by Mary McPhail Standaert, Joseph Standaert. (United States: Arcadia Publishing Incorporated,2009), page.

[41] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 82.

[42] “Richardson, Lunsford” by Norris W. Preyer, 1994. from the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, 6 volumes, edited by William S. Powell. Copyright ©1979-1996 by the University of North Carolina Press. Accessed from online website: NCPedia- https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/richardson-lunsford-0

[43] Ibid.

[44] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XI- Auditorium and Other Developments”, page 83.

[45] Ibid.

[46] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XII- Assembly Inn”, page 85.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XII- Assembly Inn”, page 86.

[50] Advertisement: Asheville Citizen-Times, September 17, 1913, page 22.

[51] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XII- Assembly Inn”, page 87.

[52] Ibid.

[53] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XII- Assembly Inn”, page 88.

[54] Ibid.

[55] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XX- The New Alba Hotel”, page 121-122.

[56] The Story of Montreat, From Its Beginning 1897-1947, “Chapter XX- The New Alba Hotel”, page 122.

[57] Asheville Citizen-Times, July 31, 1946, page 9.- newspapers.com

[58] “Memorial To Dr. Black”, The Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, NC- February 26, 1928, page 39.

[59] “North Carolina Home Damaged in Montreat Fire”, Asheville Citizen-Times, June 22, 1946, page 6. -newspapers.com

[60] “William Black Home Project To Be Erected-Presbyterians Plan Structure for Montreat”, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 27, 1949, page 32. -newspapers.com

[61] Ibid.

[62] See note in the Crosby Adams Collection of Montreat College- https://www.montreat.edu/mymontreat/library/digital-archive/crosby-adams/

[63] Asheville Citizen-Times, April 19, 1923, page 14. -newspapers.com

[64] Ibid.

[65] See Find-A-Grave.com and Ancestry.com for more information on Livingston Hadley.