By Dale Wayne Slusser- May 14, 2024

Tuberculosis, first called “phthisis” or commonly, “consumption”, had been around since ancient times, but during the 18th and 19th centuries it had turned into an insidious epidemic in Europe, Great Britain, and the United States. The term “white plague” was first used in 1861 by Oliver Wendall Holmes, an American physician and writer (think Sherlock Holmes), in comparing the enormity of the epidemic to other severe plagues, such as the “Black Plague” of the Middle Ages.[1] Also, the term “White Plague”, was used, as the wan and pallid bodies of those afflicted, would take on an extreme paleness as the disease progressed.[2] Sitting in a field between the North Fork Road and the North Fork of the Swannanoa River just west of Black Mountain, North Carolina, is an almost-abandoned three-story brick building, which is a surviving reminder to us that Asheville and Black Mountain were once at the center of the fight against the “White Plague”!

By the mid-19th century, tuberculosis was a raging epidemic in Great Britian and Europe, where annual mortality rates were between 800 and 1,000 per 100,000 per year. Between 1851 and 1910 in England and Wales four million died from tuberculosis, more than one third of those were aged 15 to 34 and half of those aged 20 to 24 died”.[3] Sanatoriums were established to isolate the sick and provide treatment. “The American sanatorium movement was based on the experience of the Europeans, who believed that fresh air was the key to treatment of tuberculosis.”[4]

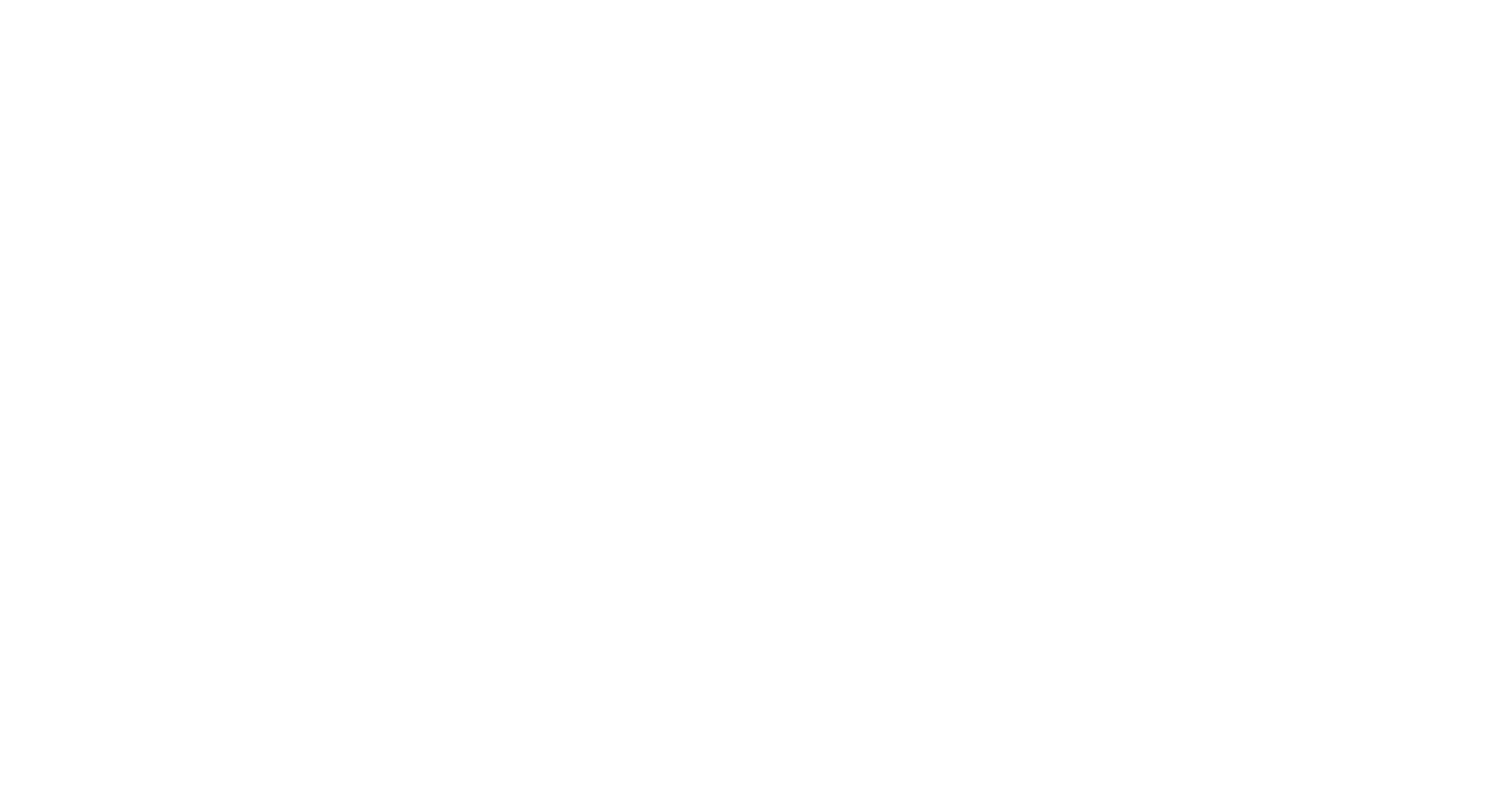

The first sanatorium for tuberculosis to be established in the United States, was established in the mountains of Western North Carolina, though historians have over the years been confused on “who” founded this first sanatorium. John Preston Arthur in his 1914 book, Western North Carolina: A History From 1730-1913, writes: “In 1871 he [Judge E. A. Aston] interested the Gatchel brothers in establishing the first sanatorium at Forest Hill”.[5] Noted historian Foster A. Sondley, in his 1930 tome, A History of Buncombe County, writes: “…in 1871, two physicians by the name of Gatchell established a sanatorium at Forest Hill, then just south of Asheville’s corporate limits. After some while this undertaking was discontinued and then later revived by one of them at the northeastern corner of Haywood and College Streets, which he named “The Villa”.[6] The confusion is quite explainable, as not only was there a family of “Dr. Gatchell”, but also at least four of them were in Asheville during separate periods. To add to the confusion, more recent historians have claimed that “Dr. Gatchell” was Dr. Horatio Page Gatchell, the patriarch of the Gatchell family of physicians. Let me see if I can adequately unravel this confusion and replace it with the facts. Just a note here-that we modern-day historians do have a greater advantage as we have access to primary sources, such old newspapers and digitized old deeds and documents, which were not available to earlier historians.

Horatio P. Gatchell, Sr. was born in Hallowell, Maine, in 1815. He first graduated from Bowdoin College in 1836, where he had prepared himself for the pulpit and for a teacher. But, shortly after marrying Anna M. Crane of Cincinnati, OH in 1840, H. P. Gatchell attended the Louisville Medical School, and the following year the Reform Medical School of Cincinnati, graduating from the latter in 1842. In 1849 he was appointed Professor of Anatomy in the Institute. Resigning at the end of the spring term of 1851 , he accepted, in April, the chair of Anatomy in the Western College of Homeopathic Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio. From 1851 to 1854 he was coeditor of the American Magazine of Homeopathy and Hydropathy; from 1869 to 1884, of the American Homeopathic Observer, and from 1868 to 1870, of the United States Medical and Surgical Journal.[7] It was Dr. H. P. Gatchell’s editorial work and writing in 1869 which first drew the nation’s attention to Asheville. In March of 1869, Dr. H. P. Gatchell, wrote a letter to fellow homeopathic physician Dr. E. A. Lodge of Detroit, Michigan, titled “Some Account of the Valley of North Carolina”. Dr. E. A. Lodge was then the General Editor for the American Homeopathic Observer, where Dr. H. P. Gatchell was also an editor, of the “Department of Physiology and Principles of Medicine”. The article was first published in its entirety in the March 11, 1869 edition of The Kenosha Telegraph[8], as well as in the March issue of the American Homeopathic Observer[9]. However, Dr. H. P. Gatchell had not actually visited Asheville at that time, and in fact he was then living in Kenosha, Wisconsin, where he and his wife, Dr. Anna Marie Gatchell, ran the Oak Grove Sanitarium[10], which specialized in “water cure” treatments, also known as “hydropathy”, akin to the then popular healing baths and mineral springs.

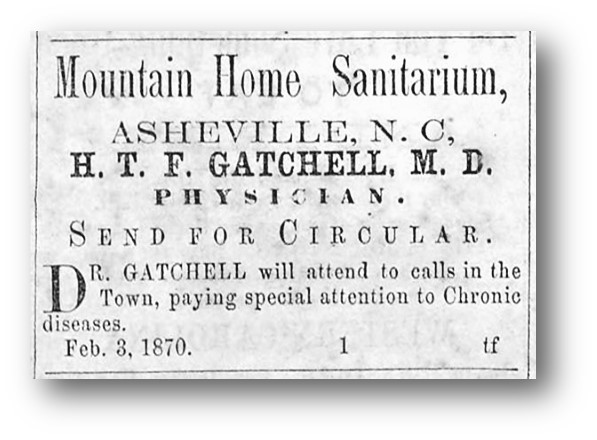

However, just a few months later, in May of 1869, Dr. H. P. Gatchell sent his 18 year-old son, C. B. F. (Charles) Gatchell from Kenosha, Wisconsin, who was suffering with pulmonary tuberculosis on a “prospecting tour”.[11] Charles Gatchell, was followed to Asheville a few months later, in September 1869, by his older brother, Dr. H. T. F. Gatchell (25 years-old), who was also suffering from a “pulmonary affection”. Dr. H. T. F. Gatchell had first gone into partnership to practice Homeopathy medicine with Dr. John Gridley, in Kenosha, WI in 1866. But, a few months later, he went out on his own, setting up his own practice in “S. Y. Brande’s building” at the corner of Main and Pearl Streets in Kenosha.[12] Six weeks after joining his brother Charles in Asheville, Dr. H. T. F. Gatchell, not only was feeling better, but had noted that his brother Charles was also showing signs of improvement. In a November 1869 letter to the editor of the New England Medical Gazette, Dr. H. T. F. Gatchell, writing from Asheville, NC, made the following report:

DEAR GAZETTE: Permit me, through the readers of the Gazette, to call the attention of sufferers from pulmonary diseases, and especially from that terrible scourge, consumption, to this region most desirable to that class of invalids. Last May, my younger brother came here in consequence of the development of pulmonary tuberculosis. He has gained strength every week, and has not had a sick day since he came. His chest has increased in circumference from two to three inches; and that without any specific exercise to effect this change. It is the result of an altitude – 2,250 feet above tide-water -sufficient to promote deep breathing and development of the chest, without being so great as to render the air too rare for breathing with comfort. It is in these particulars a happy medium. The atmosphere exerts a wonderfully exhilarating and invigorating influence, causing one to become erect and to throw the chest out. Finding myself suffering from a pulmonary affection, six weeks ago I came to this place, and I have since gained at the rate of a pound a week. – HENRY T. F. GATCHELL, M.D.[13]

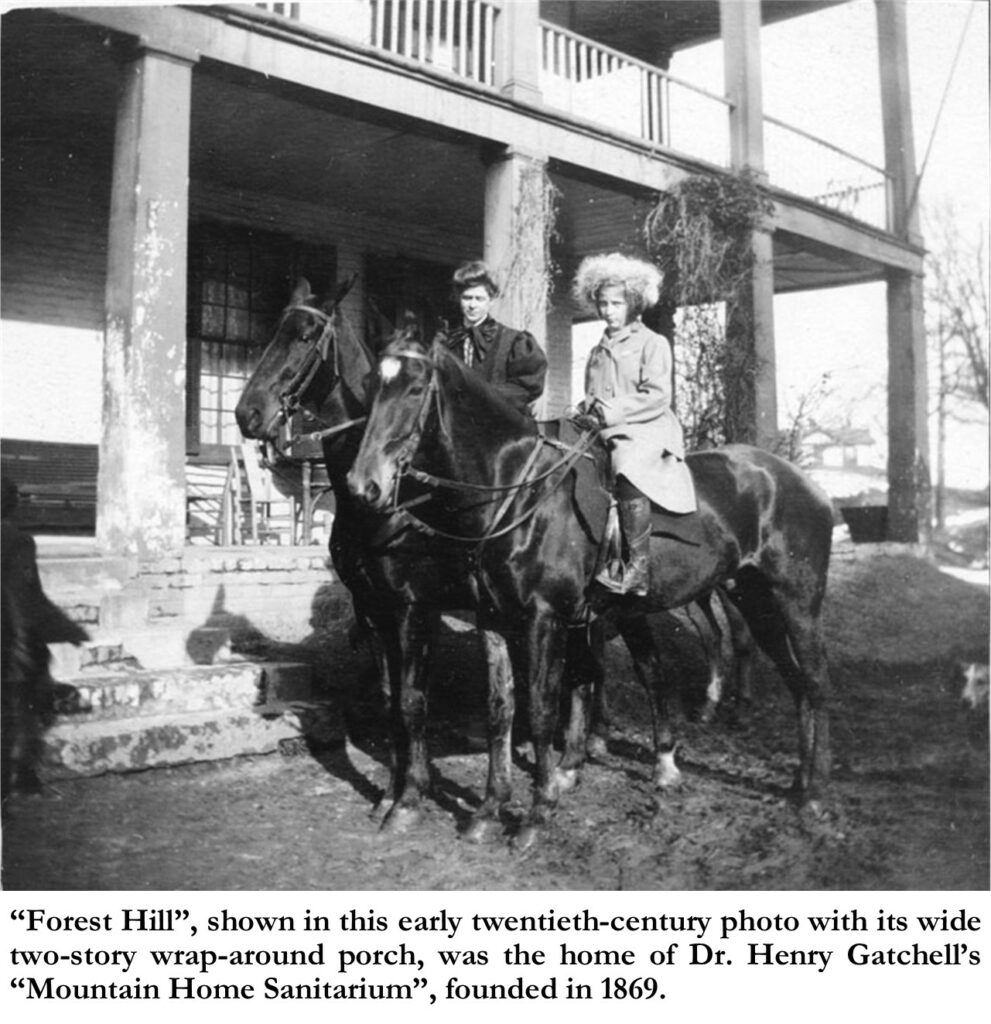

Dr. Henry T. F. Gatchell was so pleased with the climate of Asheville that he decided to set up practice. In October of 1869, H. T. F. Gatchell leased “Forest Hill” from J. M. and Eliza Baird, and opened the “Mountain Home Sanitarium”,[14] the first sanitorium for tuberculosis in the United States. Gatchell leased “Forest Hill” (which sat on a knoll atop what is now Arden Road in the Kenilworth area) from the Bairds for an annual rent of $650 for a two-year term. In addition, the Bairds also gave Gatchell a purchase option for $10,000 (to be made in three installments).[15] The lease also included many of the furnishings, specifically: 8 bedsteads, 2 washstands, 9 chamber pots, 10 lamps, 2 hand lamps, 4 looking glasses (mirrors), 12 carpets, 5 chairs, 2 pair of andirons, 2 sets of shovels & tongs, 5 parlor stoves, and 1 cook stove-all valued at $522.50.[16] Gatchell’s “Mountain Home Sanitarium” was based on the work of pioneers, Hermann Brehmer (1826-89) at Görbersdorf in Silesia and Peter Dettweiler (1837-1904) at Falkenstein in Germany, who were the first two physicians to open sanatoriums in Europe.[17] A sanatorium’s regimen planned to cure tuberculosis using the principles of hygiene: isolation, fresh air, exercise, and good nutrition.[18] Gatchell’s “Mountain Home Sanitorium”, had the added advantage (according to his father’s observations) of benefitting from Asheville’s altitude and mild climate. “Forest Hill” was particularly suited for use as a sanitorium with its wide two-story porches (verandahs), which surrounded the house on three sides (north, west, and south), where patients, known as “invalids” could take in the fresh mountain air on their chairs or beds. We know of at least one man and his wife who benefited from Dr. Gatchell’s care at the “Mountain Home Sanitarium.” Marcus C. Wheeler, a merchant and postmaster in Paola, Kansas, who “was on the eve of departing to another section in hope of recovering his health”,[19] happened upon an unwrapped, and therefore unaddressed, copy of The Pioneer (an Asheville newspaper), which “on perusing it”, he read Dr. Gatchell’s article, “The Salubrity of the Climate of Western North Carolina”.[20] According to Mr. Wheeler, “the article suited him so well that he left his home for Asheville, a day or two afterward”.[21] Indeed, Marcus Wheeler (age 33) and a lady named Nancy (age-27), show on the 1870 US Census as living in Asheville in the household of 26 year-old physician H. T. F. Gatchell, along with C. B. F. Gatchell (age-19).

Gatchell’s “Mountain Home Sanitarium” was based on the work of pioneers, Hermann Brehmer (1826-89) at Görbersdorf in Silesia and Peter Dettweiler (1837-1904) at Falkenstein in Germany, who were the first two physicians to open sanatoriums in Europe.[17] A sanatorium’s regimen planned to cure tuberculosis using the principles of hygiene: isolation, fresh air, exercise, and good nutrition.[18] Gatchell’s “Mountain Home Sanitorium”, had the added advantage (according to his father’s observations) of benefitting from Asheville’s altitude and mild climate. “Forest Hill” was particularly suited for use as a sanitorium with its wide two-story porches (verandahs), which surrounded the house on three sides (north, west, and south), where patients, known as “invalids” could take in the fresh mountain air on their chairs or beds. We know of at least one man and his wife who benefited from Dr. Gatchell’s care at the “Mountain Home Sanitarium.” Marcus C. Wheeler, a merchant and postmaster in Paola, Kansas, who “was on the eve of departing to another section in hope of recovering his health”,[19] happened upon an unwrapped, and therefore unaddressed, copy of The Pioneer (an Asheville newspaper), which “on perusing it”, he read Dr. Gatchell’s article, “The Salubrity of the Climate of Western North Carolina”.[20] According to Mr. Wheeler, “the article suited him so well that he left his home for Asheville, a day or two afterward”.[21] Indeed, Marcus Wheeler (age 33) and a lady named Nancy (age-27), show on the 1870 US Census as living in Asheville in the household of 26 year-old physician H. T. F. Gatchell, along with C. B. F. Gatchell (age-19).

Alas, despite all the accolades and promotions, the Mountain Home Sanitarium only lasted for two years, until 1871. Though certainly not a financial success (which is possibly why it closed so soon), it was a success for the Gatchell’s as they both recovered from their pulmonary illness. In fact, young Charles went on to attend a year of training at Hahnemann Medical College in Chicago (1872-1873), followed by a year at Pulte Medical College in Cincinnati, OH, obtaining a “First Medical Prize” [22] in 1874. Then in 1877, he was hired as the chair of the Theory and Practice of Medicine Department in the Homeopathic College of the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Michigan. Dr. Charles B. Gatchell went on to a successful career as a doctor, professor, lecturer, medical journal editor, and even managed to write several novels before his death in 1910, at the age of 59. Ironically, Charles died while having an operation to remove a bladder stone, but even more ironic was that his final few years were spent living with none other than his brother, Dr. H. T. F. Gatchell, in California![23] Also, just a note, that poor Marcus Wheeler only survived a few years after being at the Mountain Home Sanitorium, dying of tuberculosis in Hendersonville, NC in 1872.[24]

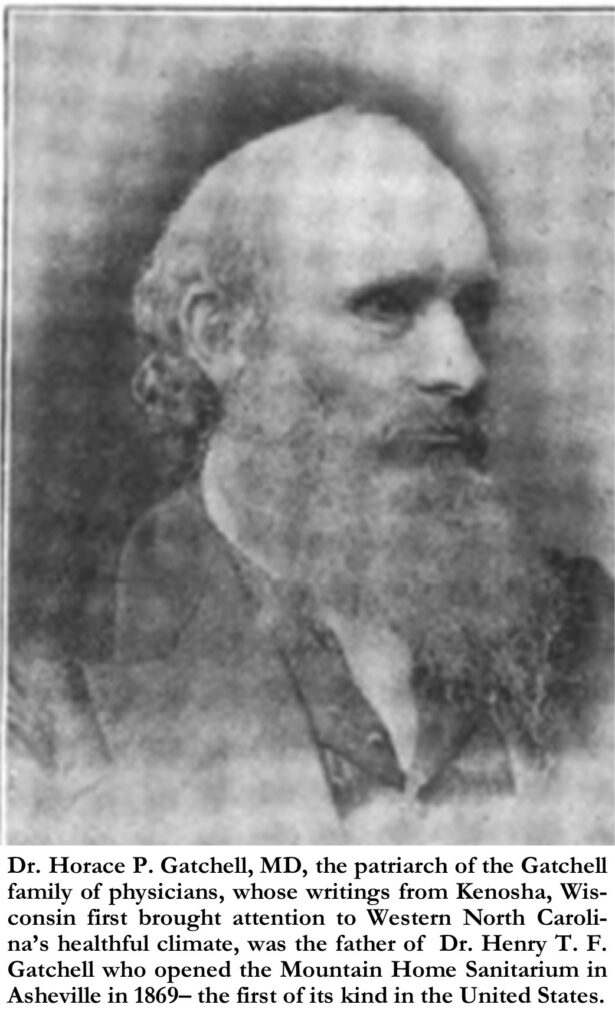

Dr. Joseph William Gleitsmann, was born in 1841 in Bamberg, Germany. He received his medical education at Würzburg, Munich, Berlin, and Vienna. Shortly after graduating from his medical education, he served in the Medical Corps of the German Army in 1866, followed by serving as a surgeon during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870.[25] Shortly thereafter, Dr. Gleitsmann emigrated to America to Baltimore, Maryland where he opened, in December of 1871, a “Free Dispensary for the Treatment of the Lungs and Throat”, [26]on Charles Street. Then in 1875, On the heels of Dr. H. T. F. Gatchell’s “Mountain Home Sanitarium”, which had closed just four years earlier, in May of 1875, Dr. J. W. Gleitsmann, decided to move to Asheville and establish the “Mountain Sanitarium For Pulmonary Diseases”. Most likely, Gleitsmann was inspired not only by the work of his European colleagues (Brehmer and Dettweiler), but also by the Gatchell family’s published reports in the various medical journals, on Asheville’s climatology and its beneficial effects for those suffering with pulmonary afflictions, specifically “consumption”.

“Mountain Sanitarium For Pulmonary Diseases” officially opened on June 1, 1875 in the “Carolina House” on North Main Street (now Broadway Street), just a block from Center Square (Pack Square). The “Carolina House” was particularly suited for a sanitarium, having formerly functioned as a boarding house/hotel, but more importantly, it had a deep and long two-story porch on its front, where “invalids” could sit in chairs or lie in beds in the “open-air.” Dr. Gleitsmann widely publicized his sanitarium in newspapers in the Northeast, South, and West. Dr. Gleitsmann’ s sanitarium was such a success that within a few years, he was leasing the former Eagle Hotel as well as the Carolina House. The regimen at the “Mountain Sanitarium”, included rest, open-air, exercise, and nutritious meals, as well as specialty medical treatments such as, “breathing gymnastics by aid of a pneumatic machine.”[27] However, despite its apparent success, the “Mountain Sanitarium For Pulmonary Diseases”, only operated for five years, until 1880, at which time Dr. Gleitsmann closed the sanitarium and moved back north. According to a later report, Dr. Gleitsmann gave his reason “for throwing up the work and leaving Asheville”[28], as due to the “failure to find a suitable house wherein to carry out the work.”[29]

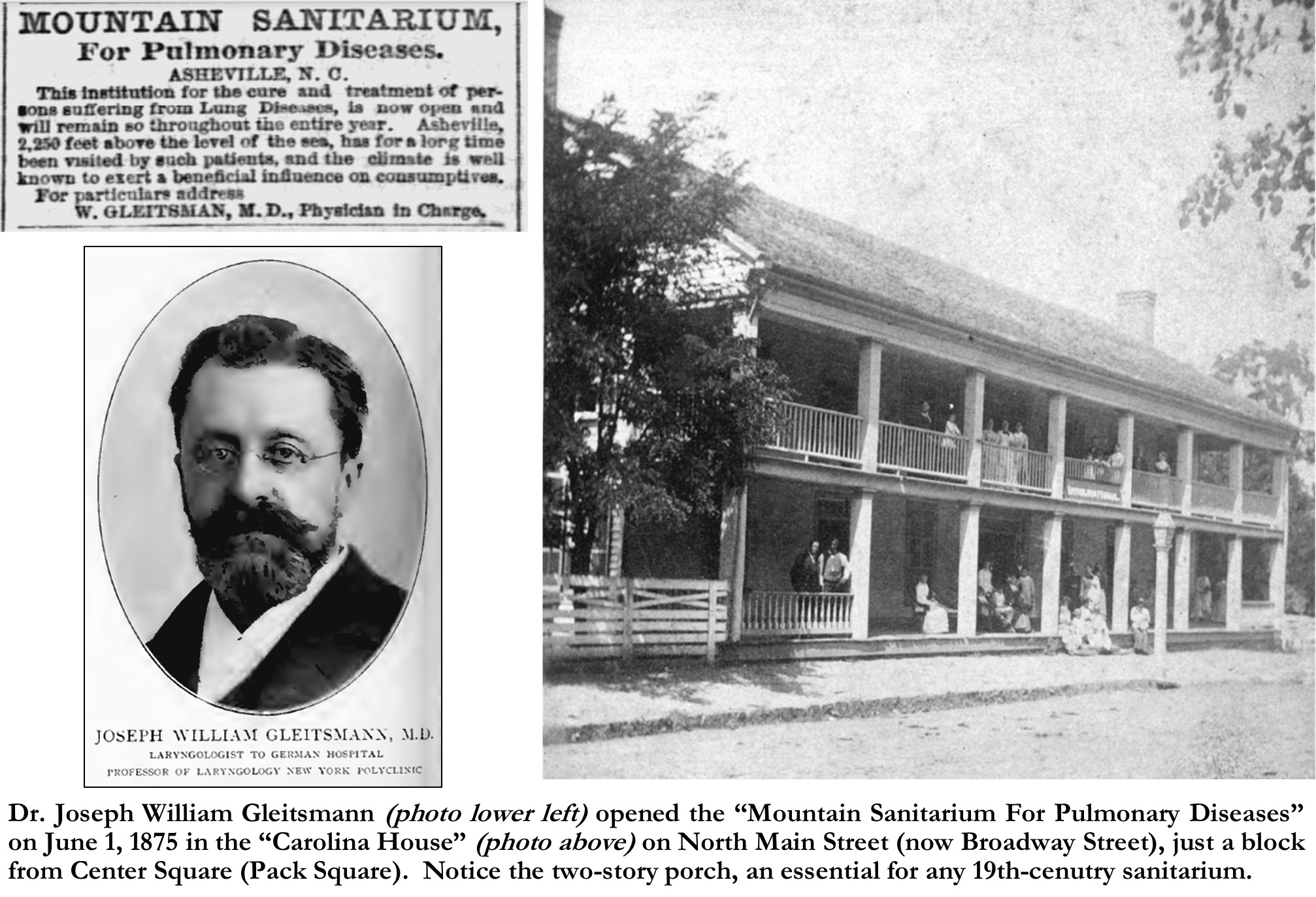

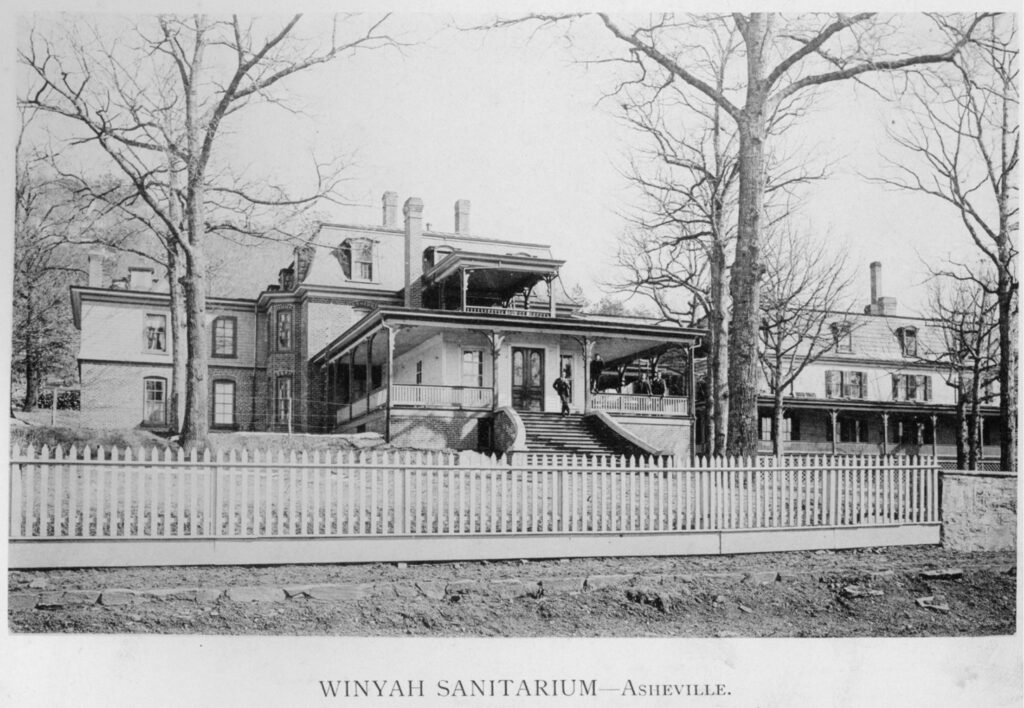

By the end of the decade, another German-American doctor came to Asheville to build upon Drs. Gatchell and Gleitzmann’s pioneering sanitariums. In 1888, Dr. Karl Von Rock came to Asheville and leased “Winyah House” from a Charlestonian preacher named Rev. A. Toomer Porter. Rev. Porter had built the “house” a year or so earlier as a hotel. “Winyah House” had opened in September of 1887, under the management of William Blatchford.[30] However, in September of 1888, just a year after its opening, “Winyah House” was leased by Dr. Von Ruck to use as a tuberculosis sanitorium.

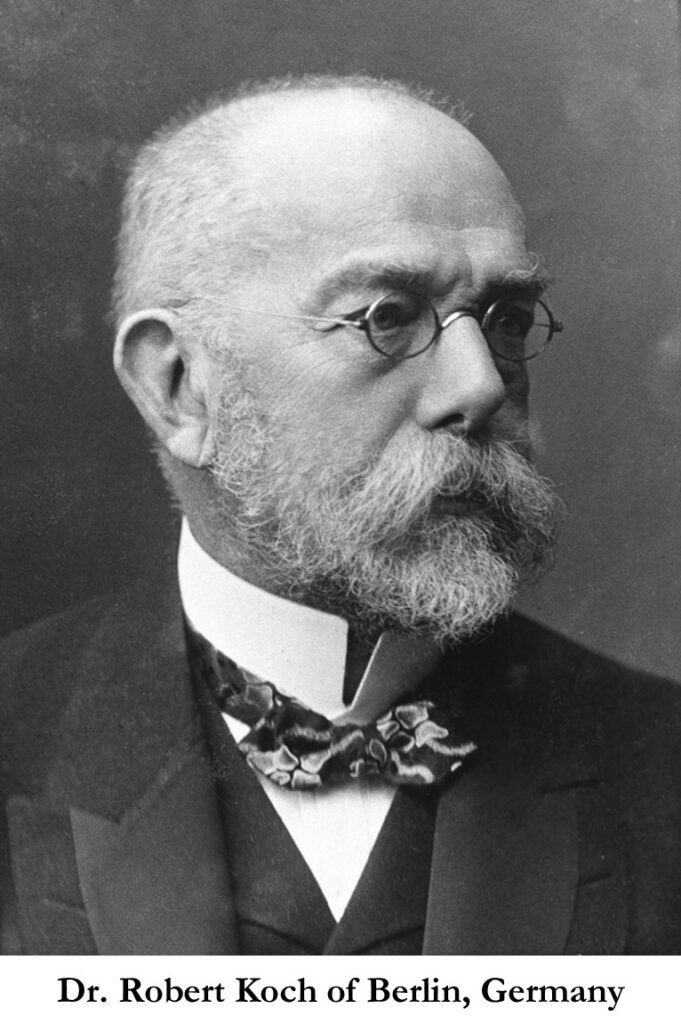

Dr. Karl Von Ruck, was born in Constantinople, Turkey in 1849, to Baron Johann and Clara von Ruck, where his father was the German minister. Spending his youth in Württemberg, Germany, Karl Von Ruck was educated in Stuttgart where he received the B.S. degree in 1867. He entered the medical course at the University of Tübingen, but the Franco-Prussian war interrupted his studies. In 1871, during the war, Von Ruck emigrated to Portage County, Ohio.[31] In 1872, Von Ruck, who was then calling himself, “Carl G. Ruck”, married Adelia Moore, a student at the nearby Oberlin College.[32] Adelia’s father, Rev. Henry D. Moore, who had been the minister at the Vine Street Congregational Church in Cincinnati, Ohio, performed the ceremony in Ottawa County, Ohio on Christmas Day of 1872.[33] Carl and Delia Ruck settled in Ohio, where their son Silvio was born in 1875, and daughter Calla, born in 1877. Just after the birth of their daughter, Carl G. Ruck enrolled at the University of Michigan, and in 1879, “Carl Von Ruck” graduated with a “Doctor of Medicine” degree.[34] Following his graduation, Von Ruck, returned to Ohio and set up a practice in Norwalk, Ohio, as “Dr. Karl Von Ruck”.[35] In January 1883, Dr. Von Ruck set out on what would be a life changing European trip, “for the purpose of making special study in the treatment of private diseases”,[36] where he planned to visit the medical schools in “Paris, Vienna, and Berlin.”[37] The most life-changing part of his trip was when “Dr. von Ruck was a pupil in Dr. Koch’s laboratory in Berlin”[38], where he “studied the methods of examination for the demonstration of the germ for Tuberculosis immediately after the discovery of that germ was announced by Dr. Koch”.[39] Just a few months earlier, on March 24, 1882, Koch had presented his findings to the Berlin Physiological Society, confirming that the tubercle bacillus, was the cause of tuberculosis.[40]

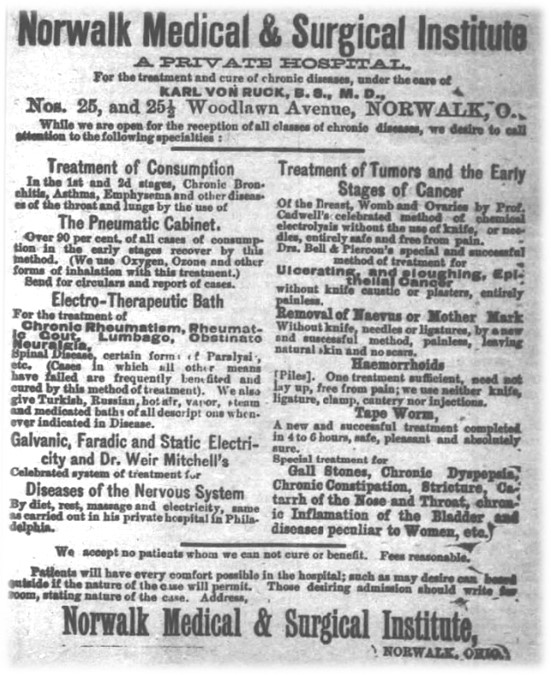

After his 1883 trip to Europe, Dr. Karl Von Ruck returned to his practice in Norwalk, and in 1886 he opened a private hospital “for the treatment of lung diseases and diseases of the heart”.[41] First opening, with eight patients, in a rented boarding house, the Norwalk Medical and Surgical Institute, was soon established at 15 and 15-1/2 Woodlawn Avenue, which were two houses that Dr. Von Ruck had purchased and connected together with a hallway, for the purpose of housing the new hospital.[42] Despite it’s apparent success, or perhaps because of it, within two years, in September 1888, Dr. Von Ruck decided to close down the Norwalk Medical and Surgical Institute and was reported to be, “OFF FOR NORTH CAROLINA!”.[43] On Wednesday, September 19, 1888, Dr. Von Ruck and his family, and entourage (cook, Thomas Kidd; housekeeper, Miss Anna Schreiber; and “several very competent girls from Norwalk”) left for Asheville, North Carolina,[44] where the doctor had leased a new hotel (in its entirety) called “Winyah House”, to house his new hospital.

“Winyah House,” which sat at the southeast corner of present-day Furman and Baird Streets, was a large brick hotel that Rev. A. Toomer Porter had built and opened in 1887 just the year before. Dr. Von Ruck decided to keep the name of the hotel as the name of his new hospital. Just a month after it opened, fellow-townsman and patient, Issac M. Underhill, made the following report back to Norwalk’s Weekly Reflector, describing the new hospital:

The Winyah House, under the management of Dr. von Ruck, is properly speaking, an invalid’s resort, although any visitor, sick or well, is made welcome. The House is beautifully located about one-half mile from the city, and has about forty rooms elegantly furnished, is heated with hot water, has gas, electric bells, etc. The table is excellent, being just what an invalid, or anyone else could desire. The Doctor brought his cook with him from Norwalk so that we don’t have to contend with southern art in that line. Application for rates, etc. are arriving daily, and I have no doubt we will have a full house by spring.

The climate is the beauty of this place. It is pure and bracing, and of great benefit in cases of lung trouble. The favorite “health practice” here is horseback riding, and the easy-going riding horses that are used make it a pleasure. Asheville is becoming more popular each year as a health resort and I think many of our Norwalk people who go to Colorado or California could profitably come here instead. It is only about a twenty four hours’ trip from Norwalk and a good place “to get home from” if necessary.[45]

Von Ruck also clearly advertised his new health resort as a sanitarium. A December 1888 advertisement read:

“The Winyah Sanitarium- For patients suffering of diseases of the lungs and throat, and conducted on the plan of the sanitarae’s at Goebersdorf and Falkenstein in Germany. Ours is the only such institution in the United States and endorsed by the leading members of the medical profession. Terms Reasonable. -KARL VON RUCK, B. S. M. D..”[46]

In 1854, Hermann Brehmer had established his pioneering sanatorium, for the systematic open-air treatment of tuberculosis, at Görbersdorf in Silesia, Germany. Brehmer advocated high altitude, abundant diet with some alcohol, and exercise in the open air under strict medical supervision.[47] Peter Dettweiler was a patient of Dr. Brehmer at Görbersdorf , who became director of the Falkenstein Lung Sanatorium in 1876. At Falkenstein, Dettweiler continued Brehmer’s work but placed a greater emphasis on rest. Dettweiler’s patients spent the day lying on chaises longues, sheltered by a roof but in the open air.[48] Clearly Von Ruck combined both models, advocating exercise, diet, and open-air treatment, all at a high mountain altitude.

Although Winyah Sanitarium sounded like a “resort,” it was a serious hospital, and Dr. Karl Von Ruck was deeply concerned with not only finding adequate treatment for those suffering with tuberculosis, but he earnestly sought to find a “cure” for the dreaded disease. On August 6, 1890, Dr. Robert Koch made a ground-breaking presentation to the Tenth International Medical Conference in Berlin in which he claimed that he had isolated a substance from tubercle bacilli that could ‘‘render harmless the pathogenic bacteria that are found in a living body and do this without disadvantage to the body”.[49] Koch named his substance, or “lymph”, tuberculin, and described it as a “brownish, transparent liquid, which does not require special care to prevent decomposition”.[50] When news of Koch’s new discovery reached Asheville, Dr. Von Ruck began to make preparations for securing some of Koch’s tuberculin serum. On November 17, 1890, just three months after Koch’s announcement, Dr. Von Ruck left Asheville for New York where he boarded a steamer ship to Berlin.[51] Dr. S. Westray Battle, another leading Asheville physician, left three days later bound also for Berlin, apparently Dr. Battle, a retired Navy surgeon, had been authorized by the “United States Navy Department to make an official observation of Koch’s discovery”.[52] The two Asheville physicians met at Dr. Koch’s a week later. Interestingly, after spending several weeks together observing Dr. Koch, the two doctors had distinctive views of the discovery. On December 24, 1890, it was reported that Dr. Battle had cabled Asheville with the report that “Results unfavorable frequently. Further investigation necessary”.[53] And yet Dr. Von Ruck was reporting that, “he believes, in properly selected cases, the treatment advocated by Dr. Koch is a success,” and that Von Ruck “expects to begin treatment here[Asheville] December 25.”[54] Von Ruck met his prediction, as he returned in time to give his first inoculation at Winyah Sanitarium on December 24, to “a young lady from South Carolina” who was suffering with tuberculosis of the larynx, and who had been at the sanitarium for three months.[55]

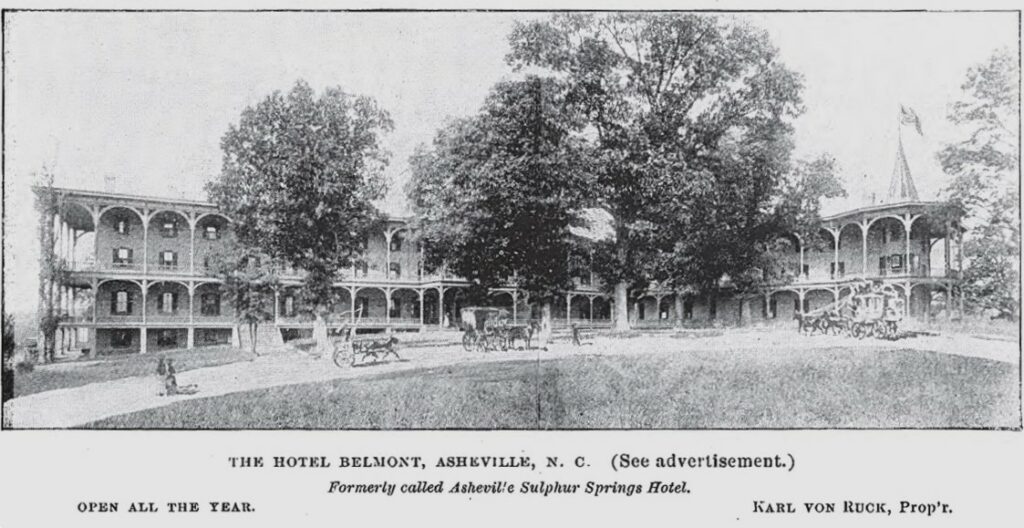

In February of 1892, Dr. Von Ruck announced that he was closing down Winyah House and moving his operations to the Hotel Belmont at Sulphur Springs in West Asheville.[56] The Hotel Belmont had been built in 1887 by Edwin Carrier, the developer of West Asheville. It first appeared that Dr. Von Ruck was abandoning the sanitarium concept and just going into the luxury hotel business. However, a few months after he opened Hotel Belmont, in April of 1892, Von Ruck announced that he had purchased twelve acres above the hotel on which he planned to build a new sanitarium.[57] The new $12,000-$15,000 sanitarium’s purpose was “to separate the invalids from those in the Hotel Belmont, which is in no sense a sanitarium.”[58] Then in June, Dr. Von Ruck announced that he had hired Col. John B. Steele to be the manager of the Hotel Belmont, and that he was going “back to the city” to re-establish his doctor’s office, this time in partnership with Dr. C. P. Ambler.[59] But then alas, all of Von Ruck’s grandiose plans literally went up in smoke. At 11:30 pm, on August 24, 1892, as 138 guests were sleeping, including Dr. Von Ruck and his family and sisters-in-law, a fire erupted at one end of the hotel, and quickly engulfed the building. Although all guests were able to escape, some by jumping out of windows or verandahs, there were many injuries, but no fatalities.[60]

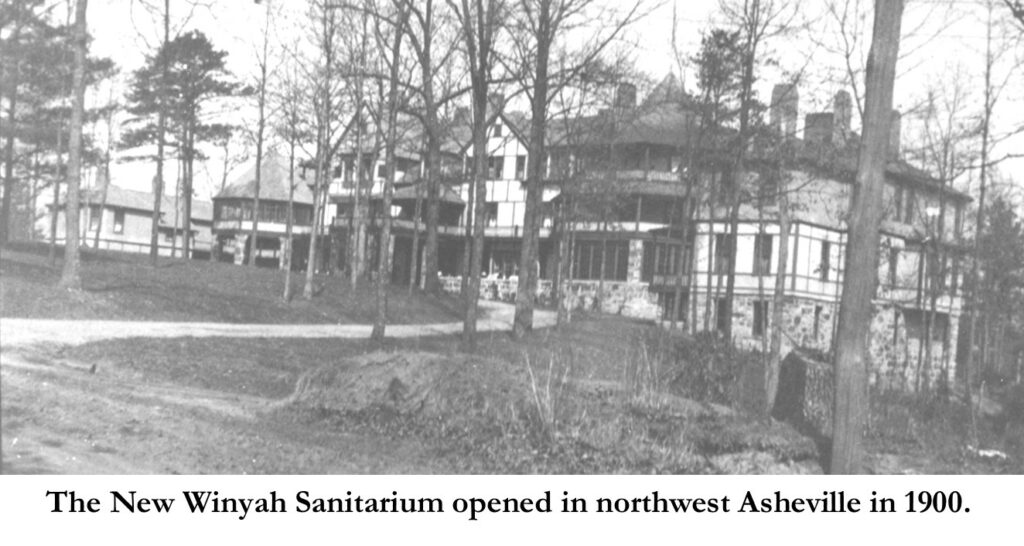

The Hotel Belmont was not rebuilt, but Dr. Von Ruck took his insurance money (like renter’s insurance-on all his furniture and equipment), and decided to lease The Winyah House from Dr. Porter and in November of 1892, Dr. Von Ruck reopened the Winyah Sanitarium at its former location off Charlotte Street in Asheville.[61] Dr. Von Ruck finally realized his dream of building a new sanitarium, when in January of 1900, he opened the “New Winyah Sanitarium”[62], which he had built in Ramoth, NC just north of Asheville (this location is now the northeast corner of the intersection of Spears Avenue and Mt. Clare Street within the Asheville city limits).

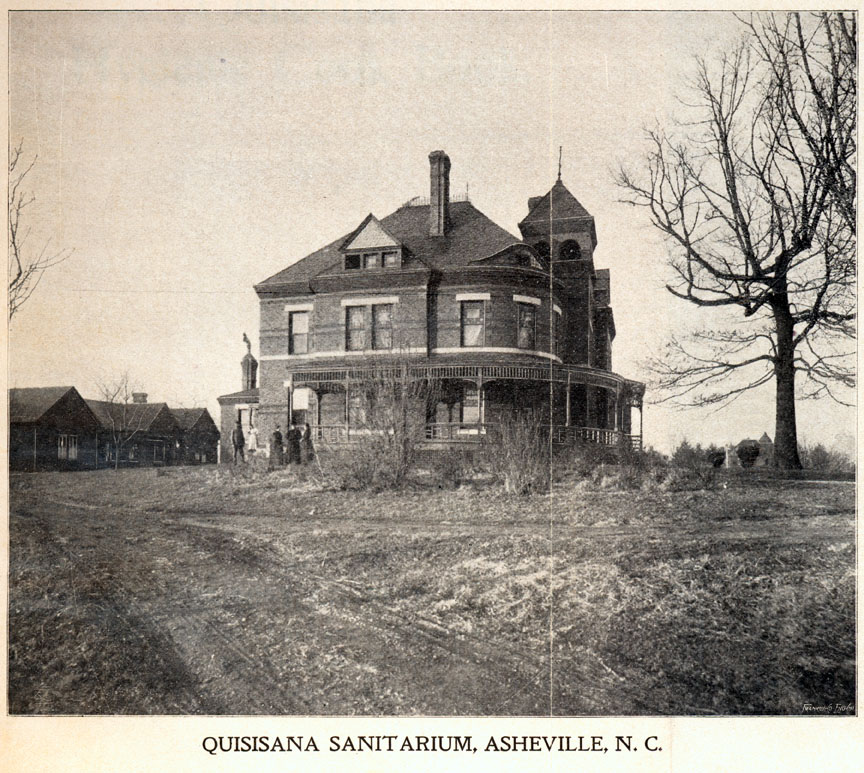

In the United States “tuberculosis of the lungs (aka “consumption” or “phthisis”) was one of the two leading causes of death in the early 1900s (the other was pneumonia).” [63] Consequently, by 1900, Asheville and its environs were widely known and promoted as THE place for seeking healing and treatment for tuberculosis. At that time, smaller sanitoriums began opening up in Asheville, like the Quisisana Sanitarium and the Oakland Heights Sanitarium, however these were more like spas than medical facilities, as they advertised, “No Medicine! No Surgeries!” and offered “Massage, Baths, Diet” and “Swedish Movements” (exercises).[64]

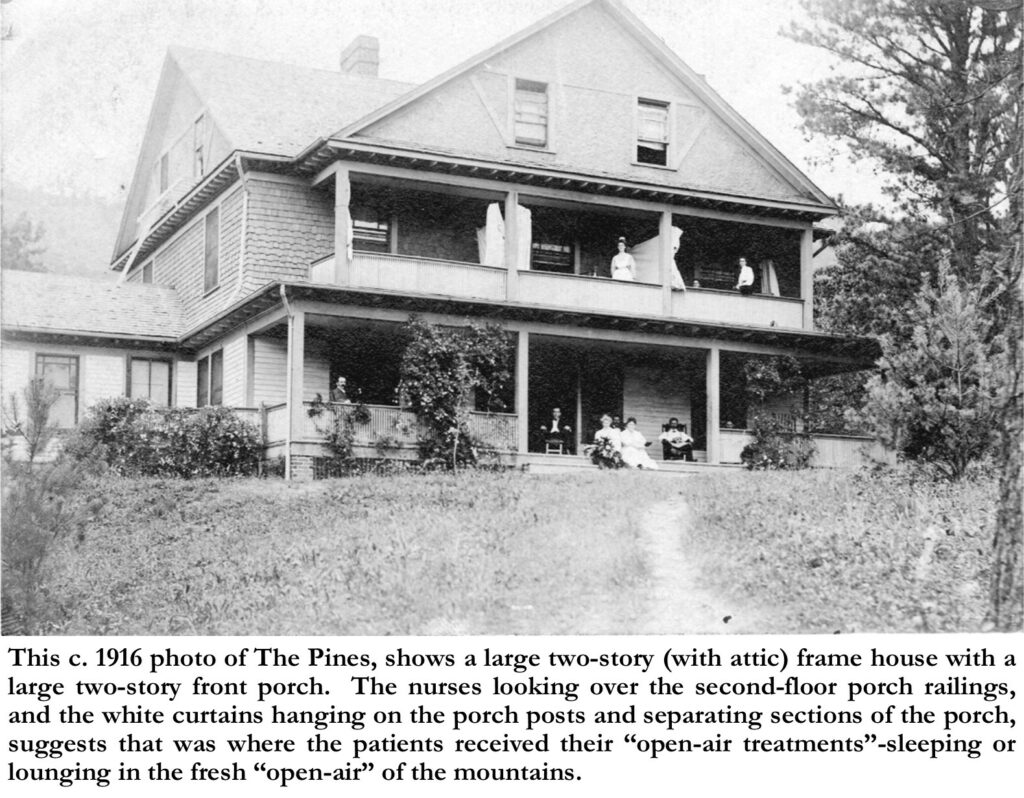

In 1897, the Mountain Retreat Association (Montreat) was established as a religious conference and retreat center in Black Mountain, NC just a few miles east of Asheville. Although it was not a sanitarium, missionaries and Christian workers saw and used Montreat as a place for physical as well as spiritual rest and restoration. In the winter of 1898-1899, Dr. C. E. Cotton, of Cleveland, Ohio came to Montreat for rest. In September 1898, Dr. Cotton had purchased two lots on the Mountain Retreat Association grounds,[65] which he most likely erected a tent or small shelter. Having been convinced of the superb “climate and health conditions” of Black Mountain, in September of 1899, Dr. Cotton purchased a 75-acre tract, just outside of the Montreat gate,[66] on which to build a sanitorium. Construction of the new sanitarium began the following summer (July 1900)[67] and was completed by the Fall of 1901.[68] Named “The Pines”, Dr. Cotton’s sanitarium, was a smaller facility, with a capacity of 15 patients and sat on a knoll amongst a grove of Pine trees. The sanitarium was for those who were in the early stage of tuberculosis, or those needing post-operative care, from “such surgical cases as are due to Tubercular origin”[69]. Acting much like our modern-day post-operative rehabilitation facilities, The Pines provided physical therapy services (though they did not call them such) such “Dietetic- Hygienic Treatment,” baths, massages, and open-air treatments. They even advertised that “Tuberculin is used in selected and suitable cases.”[70]

A surviving photo of The Pines, shows a large two-story (with attic) frame house with a large two-story front porch. The nurses looking over the second-floor porch railings, and the white curtains hanging on the porch posts and separating sections of the porch, suggests that was where the patients received their “open-air treatments”-sleeping or lounging in the fresh “open-air” of the mountains.

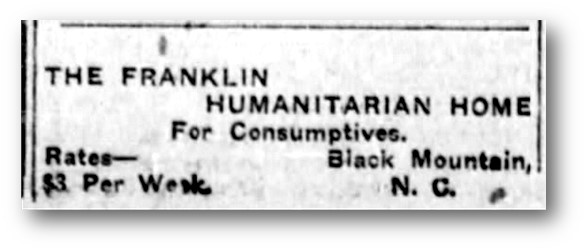

Soon, Black Mountain was being seen as perhaps even more beneficial for physical healing and restoration than Asheville, as it was more rural and tranquil, and yet was at the same altitude of Asheville or higher. In 1902, Mrs. M. Franklin Mallory opened the “Franklin Humanitarian Home” in the former Black Mountain Inn at nearby Black Mountain.[71] Sadly, Mrs. Mallory’s sanitarium only lasted for four years until her untimely death in 1906 (she was hit by a train while walking on the tracks near her home).[72] But then in 1903, the Chicago newspaper made the following announcement:

Dr. W. K. Harrison is at the head of a syndicate which has purchased a tract of 700 acres about ten miles distant from Asheville, N. C., near Black Mountain, which is to be developed into a health resort. One sanitarium is to be built by Dr. Harrison, and the other is contemplated by the Royal League for the care of invalid members of the order.[73]

Dr. W. K. Harrison was the Head Medical Director for the Royal League fraternity, based in Chicago, IL. The Royal League, an offshoot of the Royal Arcanum, was founded in 1883, as a “mutual assessment beneficiary fraternity” which functioned both as a fraternity and as a life and health insurance group, accepting men between twenty-one and forty-six years of age to provide “a widow’s and orphan’s benefit fund, from which, at the death of members, it would pay $2,000 or $4,000 to their families or dependents”.[74] The Royal League was also described as making “a feature of the social side of the organization, with the reading of papers, debates, and other entertainments”. The government of the latter is vested in a Supreme Council, with Advisory Councils in States having the necessary membership. [75]

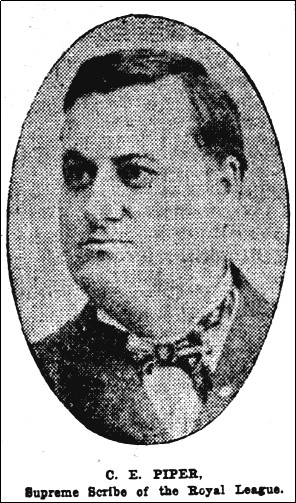

The “syndicate” mentioned in the first announcement, consisted of Dr. Wallace K. Harrison, Medical Director of the Royal League, Dr. Issac J. Archer, Assistant Medical Director of the Royal League, and Charles J. Piper, Supreme Scribe (Secretary) of the Royal League. The Fellowship Association of the Royal League[76] had been formed in Chicago in July of 1903[77], as a separate yet adjunct entity to establish and operate the Royal Legue Sanitarium at Black Mountain, NC.

Logistically, Dr. Harrison and his wife first purchased the 520-acre site, for the new sanatorium, in their names, in 1903, from John Gragg[78]. Later, they sold a portion of it (fifty acres) to the Fellowship Association of the Royal League. The funds to purchase the land and build the Royal League Sanatorium came from “voluntary contributions of the members of the order, no one being permitted to give more than one dollar..”[79]

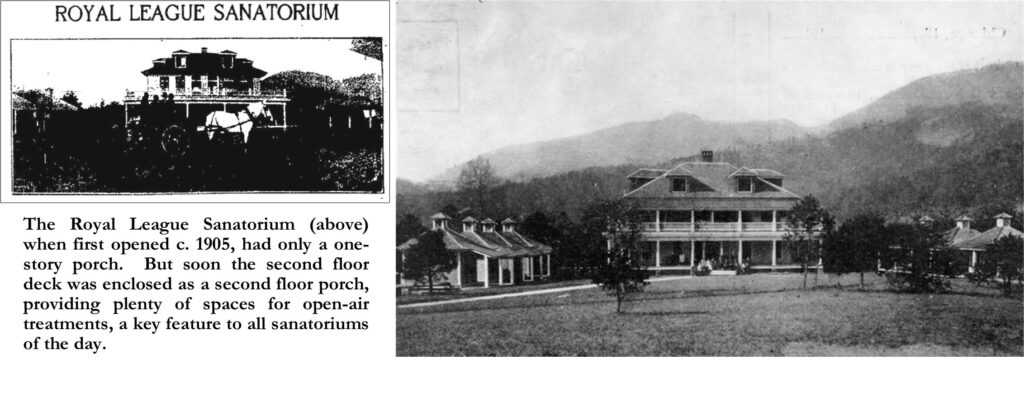

Construction of the Royal League Sanatorium began in 1904 on the fifty-acre site along the North Fork of the Swannanoa River, on the westside of the North Fork Road, just outside of the town of Black Mountain. The main building that was constructed was a two-story wood-frame building with “24 rooms” and could “accommodate twenty patients”.[80] Initially the main building was built with a first-story wrap around porch, later a wrap-around second-story porch was added on top of the first story porch. Eventually, twelve cottages would be built surrounding the main building. Construction was completed and the sanatorium was officially opened in August of 1905.[81] This was the first tuberculosis sanatorium to be established by a fraternal society in the United States.

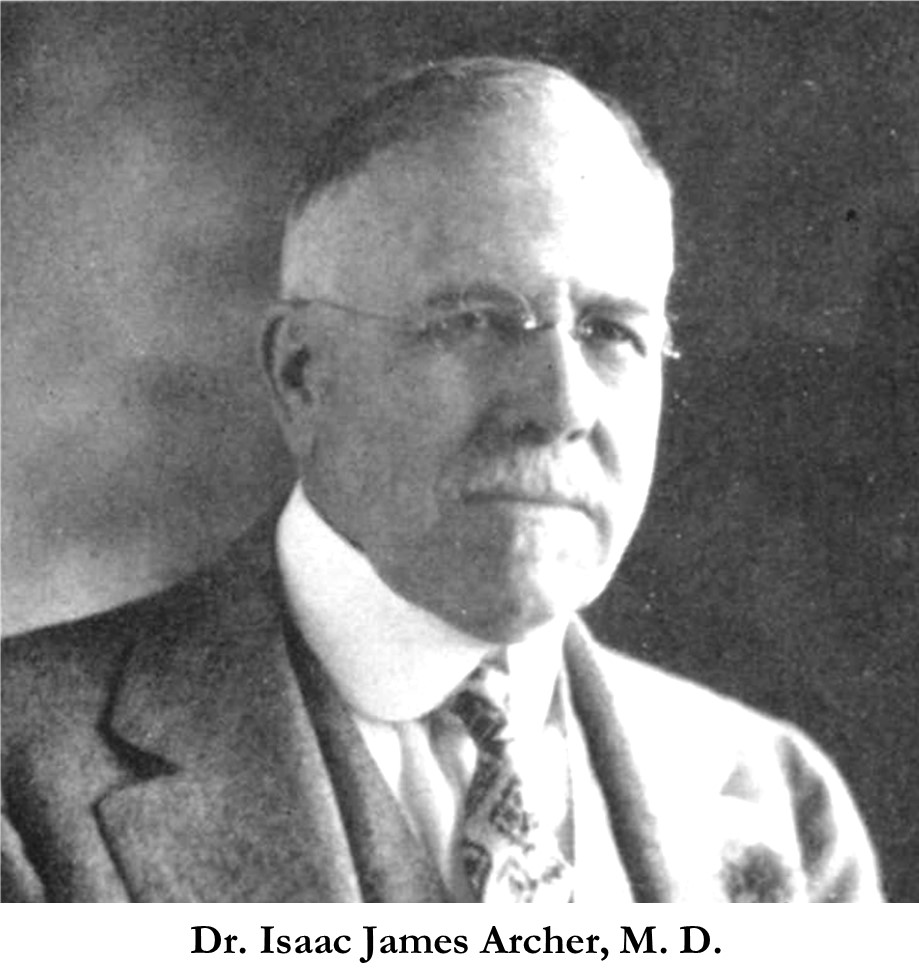

The Fellowship Association of the Royal League, sent their Assistant Medical Examiner, Dr. I. J. Archer, from Chicago in 1904 to direct the construction of the new sanatorium. In 1905, when the Royal League was opened, Dr. Archer became the director/manager of the new Royal League Sanatorium. Dr. Archer was also one of the chief shareholders in the “syndicate” that had purchased the land and had initiated the sanatorium’s construction. Dr. Issac James Archer was born in Henderson County, Illinois on October 28, 1862. He obtained his M. D. degree at Northwestern University in 1892. He set up a practice in Berwyn, IL shortly after his graduation, but soon thereafter he was hired by the Royal League in Chicago to be the society’s assistant medical examiner. Dr. Archer was the only one of the three “syndicate” leaders to move to Black Mountain and make it his permanent home.

The Fellowship Association of the Royal League, sent their Assistant Medical Examiner, Dr. I. J. Archer, from Chicago in 1904 to direct the construction of the new sanatorium. In 1905, when the Royal League was opened, Dr. Archer became the director/manager of the new Royal League Sanatorium. Dr. Archer was also one of the chief shareholders in the “syndicate” that had purchased the land and had initiated the sanatorium’s construction. Dr. Issac James Archer was born in Henderson County, Illinois on October 28, 1862. He obtained his M. D. degree at Northwestern University in 1892. He set up a practice in Berwyn, IL shortly after his graduation, but soon thereafter he was hired by the Royal League in Chicago to be the society’s assistant medical examiner. Dr. Archer was the only one of the three “syndicate” leaders to move to Black Mountain and make it his permanent home.

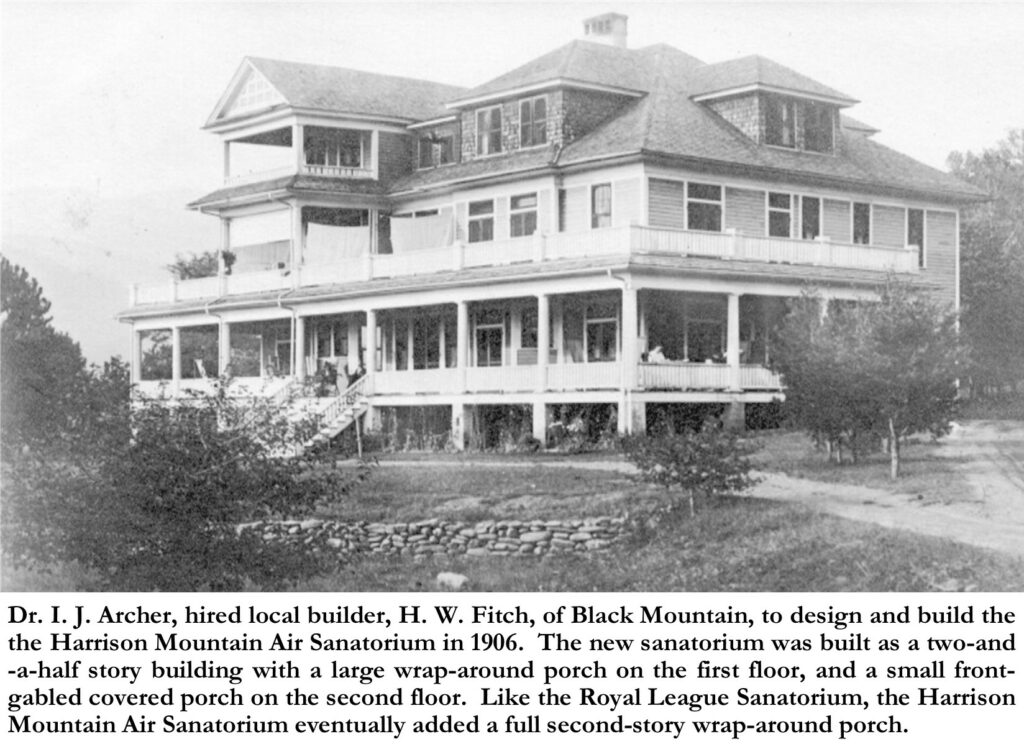

Shortly after the Royal League Sanatorium, which was only for its members, was completed, construction of a second sanatorium was begun just across the road northeast of the Royal League Sanatorium. This second sanatorium was built by the “Harrison Mountain Air Sanatorium Company.” The “Harrison Mountain Air Sanatorium Company,” was formed at Black Mountain in 1905, with the same three members of the Fellowship Association of the Royal League. The company was formed with $25,000 in capital divided into 250 shares of $100 each. Doctors Harrison and Archer each held 123 shares, with Piper holding the remaining 4 shares.[82] Interestingly, although Charles Piper was the minority shareholder of the company, a contemporary account credited him as the prime initiator of the entire project:

Something like three years ago [1903], Charles E. Piper, supreme scribe of the Royal League, conceived the idea of the institution. He told his brother officials of his “dream.” They thought well of it. A consultation was held, and Dr. Wallace K. Harrison, supreme medical examiner of the order, was instructed to go and search for a climate adapted to the care of pulmonary diseases. After diligent investigation, the foothills of the Black mountains, where the breezes are laden with piney perfumes, was chosen.[83]

Dr. Archer, of the Royal League Sanatorium (just across the road), not only directed the construction of the “Harrison Mountain Air Sanatorium,” but he was also put in charge of its management as well when it opened in 1906. Dr. I. J. Archer, hired local builder, H. W. Fitch, of Black Mountain, to design and build this new sanatorium. The new sanatorium was built with two-and-a-half stories with a large wrap-around porch on the first floor, and a small front-gabled covered porch on the second floor. Like the Royal League Sanatorium, the Harrison Mountain Air Sanatorium eventually added a full second-story wrap-around porch. This sanatorium, was slightly larger than the Royal League with a capacity of thirty patients. The rates at the Royal League were $1 per day, if you could afford it, if not then it was no charge for members of the order. However, although not limited to Royal League members, the rates at the Harrison Mountain Air Sanatorium were much higher at “$20.00 to $35.00 per week”.[84] Admirably, both of Dr. Archer’s sanatoriums, unlike other nearby sanatoriums in Asheville and Black Mountain who only admitted those with incipient or early cases of tuberculosis, were both opened “for all classes of cases”![85]

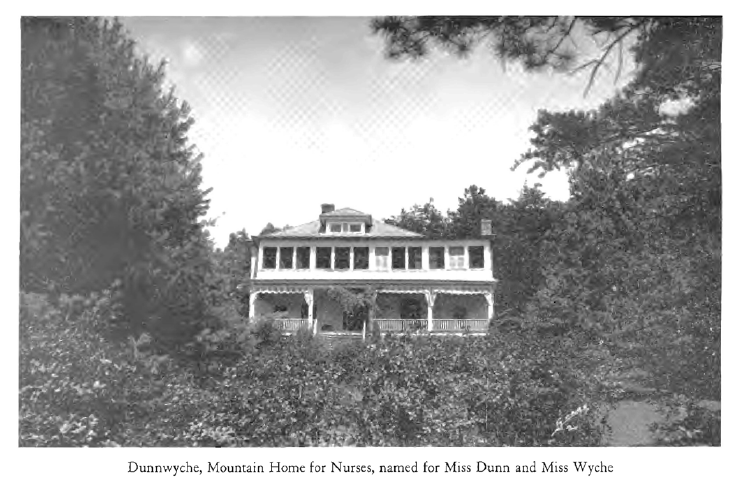

In 1911, Dr. Archer donated a two-acre site on the Harrison Mountain Air Sanatorium campus to the North Carolina Association of Trained Nurses, on which to build a home for invalid nurses.[86] Not only would the Nurses Home have access to the site’s “pure and abundant water supply”, but also Dr. Archer also “generously offered to give his services to the institution”.[87] Named Dunnwyche, in honor of nursing leaders Birdie Dunn and Mary Wyche, the new mini-sanatorium opened in 1913. The home had nine bedrooms, and like the other two sanatoriums nearby, had a large open-air front porch. Sadly, the Nurses Association had difficulties keeping the home operating, and then the World War 1 put added strain on the institution, and it was closed down and the property was sold in 1919, just six years after its opening.[88]

The Harrison Mountain Air Sanatorium continued to thrive, though in 1917 it reorganized as the Cragmont Sanatorium Company. The stockholders of the new company were Dr. I. J. Archer and Charles J. Piper, as majority shareholders of the 250 shares, with F. M. Graham and G. F. Adams having only one share each.[89] The new name was probably suggested from the Gragg family name (original owners of the site) and also certainly from the site itself which sat on the foothills with a view to the Craggy Mountains to the west. “Cragmont Sanatorium” continued to accept patients and thrive for the ensuing two-and-a-half decades.

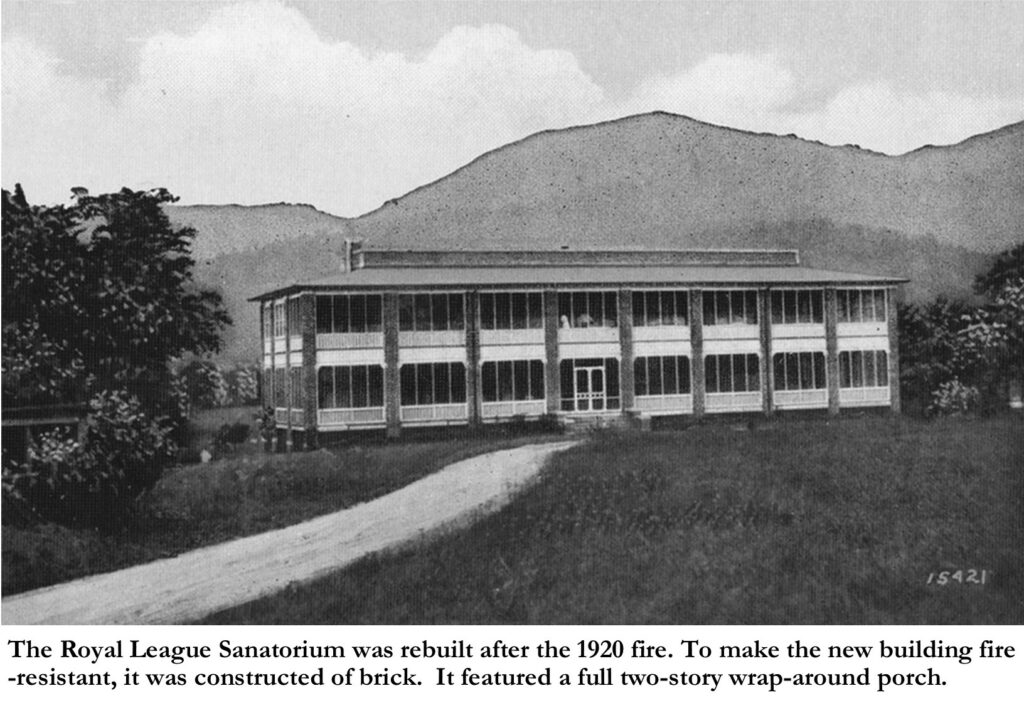

On February 15, 1920, the Royal League Sanatorium caught fire, and the entire wood-frame main building and surrounding wood cottages all burned to the ground. Thankfully, all the patients were unharmed, and were able to be transferred to Cragmont, Dunnwyche, and Woodside Sanatoriums.[90] Although the property was only partially covered by insurance, the decision was soon made by the Chicago office to rebuild as soon as possible.[91] Construction of a larger new brick sanatorium, at a cost of $50,000, began in May of 1920, utilizing remnants of the original foundations.[92] Two-story porches were part of the design of the new sanatorium.

The rebuilt Royal League Sanatorium re-opened in 1922 with a capacity of 30 beds.[93] When asked in 1928, “Why A Fraternal Sanatorium?”, Dr. Archer gave “three outstanding points of superiority”, which he thought that the Royal League Sanatorium provided over public institutions: “1. Sense of personal and proprietory interest.; 2. Satisfying menu of well-prepared food.; 3. Contentment of Mind.”[94] The first point was the personalized care that they could give to their patients, and the second point was the well prepared nutritious meals that they offered using home grown produce. The third point, was a reference to the Sanatorium’s “superb location in a setting of beautiful mountain scenery”[95], where “Every room and every porch to every room looks out on a resplendent panorama of unexcelled beauty and interest.”[96] Dr. Archer continued to manage and operate both sanatoriums through the 1920’s and the 1930’s. In fact, in 1929, the Royal League Sanatorium purchased their first x-ray equipment and added their first x-ray technician to their staff. However, by 1933, the Royal League was talking of possible closure. In June of 1933, Dr. W. K. Harrison, still the head medical examiner for the Royal League, announced to the fraternity members at their quadrennial convention, that the death rate from tuberculosis was decreasing “at such a rate, that the Royal League sanatorium at Black Mountain, N. C. may be closed”.[97]

Despite the 1933 threat of closure of the Royal League Sanatorium, it was the Cragmont Sanatorium that closed first. Dr. Archer’s wife, Cornelia S. Archer, passed away in December of 1940. Then in 1944, Dr. Archer, who was then over eighty years old, became ill. He closed the sanatorium, and moved to Charlottesville, VA to be under the care of his son, Dr. Vincent Archer. The sanatorium was put up for sale in December of 1944. Dr. Isaac James Archer, who had directed two sanatoriums at the same time, for almost forty years, passed away on February 19, 1945.[98] The Cragmont Sanatorium, Inc. was dissolved.[99]. And in 1945, the property was purchased by the Original Free Will Baptists and opened as a camp and conference center, called Cragmont Assembly.[100] The original Cragmont Sanatorium building survived until being replaced by a new building in the 1970s.

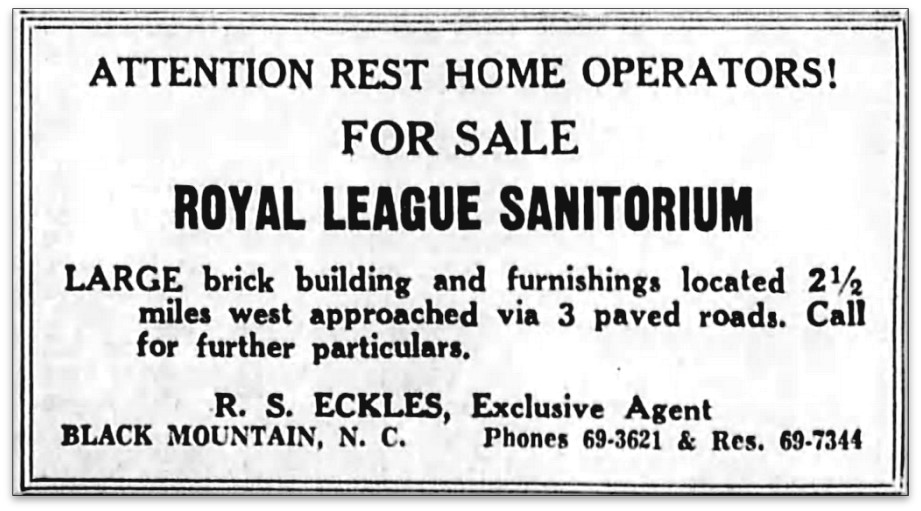

The Royal League Sanatorium continued to operate after Dr. Archer’s death. In 1947, a group of twelve members of the board of managers of the Royal League, came to Black Mountain from Chicago, and met with Dean W. Colvard of the North Carolina State Department of Agriculture, “with the view of developing farming operations and broadening the santorium’s services.” The Royal League governing board had decided to turn the sanatorium into a “convalescent home for their members and families recuperating from illness” and establish a self-sufficient farm to provide their own farm products for the home.[101] Although these changes were made, just a few years later, in 1955 the Royal League hired local real estate agent R. S. Eckles to look for a buyer. “ATTENTION REST HOME OPERATORS!”, FOR SALE- ROYAL LEAGUE SANITORIUM”, announced the sales advertisement.[102] Wholesale businessman and real estate investor, Southgate Alexis Spencer, of Nash County, NC, purchased the property in June of 1958.[103] Three months later, in September of 1958, Spencer sold the Royal League Sanatorium property to Bishop W. J. Walls and the trustees of the Western North Carolina African Methodist Episcopal Zion Conference.[104]

In the summer of 1959, the former Royal League Sanatorium, opened as Camp Dorothy Walls,[105] a camp and conference center named for Bishop Walls’ wife. Camp Dorothy Walls used the former brick sanatorium building as the “main building” on their new 61-acre tract.[106] Over the ensuing years, several new buildings were built on the camp’s property on the east side of North Fork Road, just across the road from their original main building, centering their operations onto the eastern part of the camp. Although the old brick former Royal League Sanatorium is still standing, it now sits marooned from the camp’s major operations.

The Royal League Sanatorium, which in 1947 before it closed down, was reported to have “cared for more than 700 members”,[107] still stands as a reminder that since the 1860’s, Asheville and Black Mountain has played a major role in America’s battle with the long-term epidemic of tuberculosis, which because of its longevity and severity was once called “The White Plague”. This building needs to be preserved in honor of not only those 700 that it served, but also in honor of those many who, over the past two and a half centuries have sought and found healing in the sanatoriums of Western North Carolina.

Photo credits: Note: All cropping and added captions by Dale W. Slusser

- Royal League photo– photo by Dale W. Slusser, 2024.

- Dr. Horace P. Gatchell– History of the Eclectic Medical Institute, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1845-1902, by Harvey Wickes Felter. (Cincinnati, OH: Alumnae Association of the Eclectic Medical Institute, 1902), page 100.

- Dr. Gatchell’s Mountain Home Sanitarium– The Semi-Weekly Citizen, Asheville, NC, June 2, 18970, page 4.

- “Forest Hill” home of the Mountain Home Sanitarium– Image D026-4 -Visitors, a woman and a girl, on horseback, in front of the Forest Hill Inn. Dated 1905-1906, from C.D. Howe scrapbook.- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

- Mountain Sanitarium For Pulmonary Diseases–Chicago Tribune, Chicago, IL, July 28, 1875, page 7.

- Dr. Joseph Gleitsmann– Notable New Yorkers of 1896-1899, New York, NY: Moses King, 1899) page 350.

- Carolina House– Image L601-5, Stereo view with title written on back “Carolina House”. N. Main Street, c. 1880’s.- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

- Dr. Karl Von Ruck– Image G206-5, Profile portrait of Dr. Karl Von Ruck – Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

- Norwalk Medical & Surgical Institute– The Clyde Enterprise, Clyde, Ohio, May 12, 1887, page 2.

- Winyah House Sanitarium– Image L264-DS- Digital scan of illustration in NC Reference book, “Art Work of Scenes in North Carolina,” W. H. Parish Publishing Co., 1895. – Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

- Dr. Robert Koch-https://ihm.nlm.nih.gov/images/B16691- This image is a work of the National Institutes of Health, part of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, taken or made as part of an employee’s official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain.

- Hotel Belmont- Belmont [formerly Sulphur Springs] Hotel, 1892. Asheville or the Sky-Land, by Harriet Adams Sawyer, (1892).

- New Winyah Sanitarium– Image A688-4- Exterior view of the second Winyah Sanitarium, completed in 1900 looking NW from Spears Ave.- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

- Quisisana Sanitarium– Image L562-DS -Scanned from frontpiece of “Quisisana Hygienic Cook Book” by Lina Kuepper, secretary of Quisisana Sanitarium. REF N.C. 641.5 K95Q Booklet printed in 1899 by French Broad Press (Manager James I. Beall, 129 Broad Street). -Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

- “The Pines”, Dr. Cotton’s Sanitarium-copy from Presbyterian Heritage Center, 318 Georgia Terrace, Montreat, NC-from the Joe & Mary Standaert Collection, Montreat, NC.

- “Franklin Humanitarian Home” Advertisement– Asheville Citizen-Times, Dec 20, 1905,·Page 6.

- The Royal League Sanitorium, c. 1906- Chicago Star, Chicago, Illinois, May 31, 1906, page 1.

- Royal League Sanitarium Photo, pre-1920.- from the collections of the Swannanoa Valley Museum, Black Mountain, NC.

- Dr. Isaac James Archer– Image E846-DS- Portraits of Asheville physicians appearing in issues of the monthly Bulletin of the Buncombe County Medical Society during the years 1939 through 1942.- 1940 (vol. IV): No. 5.- Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

- C. E. Piper– Minneapolis Journal, Minneapolis, MN, February 18, 1906, page 16.

- Harrison Mountain Air Sanatorium– labeled “Cragmont Sanatorium”- from the Joe & Mary Standaert Collection, Montreat, NC.

- Dunnwyche Nurses Home– The History of Nursing in North Carolina, by Mary Lewis Wyche (University of North Carolina Press, 1938), page 111.

- Rebuilt Royal League Sanatorium, c. 1922– from the collections of the Swannanoa Valley Museum, Black Mountain, NC.

- Royal League For Sale– Asheville Citizen-Times, August 14, 1955, page 40.

- Royal League Sanatorium at Camp Dorothy Walls– photo by Dale W. Slusser, 2024

[1] Info from: “History of Tuberculosis. Part 1 – Phthisis, consumption, and the White Plague” by John Frith. Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health, Volume 22 Number 2; June 2014. Page 32.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “A historical geography of tuberculosis sanatoria in Western North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee”, by Susan Alana Carney. Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1999. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/9798

[5] Western North Carolina: A History from 1730-1913, by John Preston Arthur, (Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1914), page 396.

[6] A History of Buncombe County, Volume 2, by Dr. F. A. Sondley, (Asheville, NC: The Advocate Printing Company, 1930), page 720.

[7] Info from: “Horatio Page Gatchell, M. D.”, History of the Eclectic Medical Institute, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1845-1902, by Harvey Wickes Felter. (Cincinnati, OH: Alumnae Association of the Eclectic Medical Institute, 1902), page 100.

[8] “Some Account of the Valley of North Carolina”, by H. P. Gatchell, M. D., The Kenosha Telegraph, Volume 29, No. 41., March 11, 1869., page 1.

[9] “The Valley of North Carolina”, by Dr. H. P. Gatchell, American Homeopathic Observer Volume 6., E. A. Lodge, General Editor, (Detroit, MI:E. A. Lodge Pharmacy, 1869) page 135-139.

[10] American Homeopathic Observer Volume 7. E. A. Lodge, General Editor, (Detroit, MI:E. A. Lodge Pharmacy, 1870) page 560.

[11] “In our issue today, may be found a letter from C. B. F. Gatchell, a son of Prof. H. P. Gatchell, of our city,who is making a prospecting tour of Western North Carolina.”, The Kenosha Telegraph, Volume 29, No. 41.,Kenosha, Wisconsin, July 8, 1869., page 5.

[12] The Kenosha Telegraph, Kenosha, Wisconsin, August 18, 1868., page 1. -newspapers.com

[13] “The Climate of Western North Carolina”, by Henry T. F. Gatchell. New England Medical Gazette: A Monthly Journal of Homeopathic Medicine, Volume 5 No. 1, January 1870, Edited by I. T. Talbot, M.D., . (Boston, MA: S. Whitney, M. D., 1870), pages 33-44. -googlebooks.com

[14] “Dr. Gatchell’s Sanitarium”, Asheville News and Farmer, November 18, 1869, page 2.

[15] 10/30/1859 J. M. & Eliza Baird to H. T. F. Gatchell, Lease Agreement-Forest Hill Db. 33 p. 280. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Asheville, NC.

[16] 10/24/1870 H. T. F. Gatchell to J. M. & Eliza Baird (parties of the second part); & Wm. M. Cocke, Trustee (party of the third part) DEED OF TRUST Db. 34 p. 15. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[17] “The Evolution of the Sanatorium: The First Half-Century, 1854-1904”, by Peter Warren. CBMH/BCHM / Volume 23:2 2006 / p. 457-476. https://scholar.archive.org/work/jhk4iuo6fjfgnltutv6hanqxze/access/wayback/http://www.cbmh.ca:80/index.php/cbmh/article/viewFile/1239/1230

[18] “The history of tuberculosis: the social role of sanatoria for the treatment of tuberculosis in Italy between the end of the 19th century and the middle of the 20th.”, editors M. Martini; V. Gazzaniga; M. Behzadifar; NL Bragazzi; I. Barberis. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene Vol. 59, 4 E323-E327. 15 Dec. 2018, doi:10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2018.59.4.1103

[19] The Morning Star, Wilmington, NC, December 9, 1869, page 1.

[20] Probably: The Asheville Pioneer, November 6, 1869, page 3.

[21] The Morning Star, Wilmington, NC, December 9, 1869, page 1.

[22] “SECOND ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT OF PULTE MEDICAL COLLEGE”, Daily Gazette, Cincinnati, OH, February 13, 1874, page 4.

[23] Info from an obituary in the composite book/scrapbook called: Biographies of Homeopathic Physicians: Collected, arranged in twenty years and now given in the Present Form to the Library of Hanemann College of Philadelphia By Thomas Bradford, M.D. For Many Years Its Librarian, Volume 30. Philadelphia, 1916. -https://archive.org/details/bradford030-jpg10-mediumsize-pdfx

[24] The Miami Republican, Paola, Kansas, May 25, 1872, page 3.

[25] Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 63 No. 3, July 18, 1914, (Chicago, IL: American Medical Association, 1914), page 257.

[26] The Baltimore Sun, December 6, 1871, page 2.

[27] “A Mountain Retreat- A Graphic Description A Resort For Consumptives”, The Daily Courier, Evansville, IN, March 2, 1879, page 2.

[28] “Medicine in Buncombe County Down to 1883; Historical and Biographical Sketches”, by Gaillard S. Tennent, M. D., Asheville, NC. Charlotte Medical Journal, Volume 28, No. 5, May 1906. (Charlotte, NC: Blakey Printing House, 1906) page 286.

[29] Ibid.

[30] “Winyah House” advertisement, Asheville Citizen-Times, August 25, 1887, page 2.

[31] 1900 United States Federal Census for Karl Von Ruch, North Carolina, Buncombe, Asheville Ward 02, District 0135. “Year of Immigration to the United States” listed as -1871. -ancestry.com

[32] General Catalogue of Oberlin College, 1833 [-] 1908: Including an Account of the Principal Events in the History of the College, with Illustrations of the College Buildings, Volumes 1833-1908, page 682.

[33] “Marriage Certificate”, dated December 25, 1872, signed by “Rev. Henry Moore”. -Ohio, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1774-1993 for Carl G. Ruck, Ottawa County, 1840 – 1875. -ancestry.com

[34] Detroit Free Press, June 27, 1879, page 7.

[35] “Norwalk Notes”, The Leader, Cleveland, OH, April 9, 1881, page 3.

[36] Norwalk Daily Reflector, 24 Jan 1883, Norwalk, Ohio, page 4.

[37] Ibid.

[38] “HE WILL GO TO BERLIN”, Asheville Citizen-Times, Nov 17, 1890,·Page 4.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Note: It has been widely published in biographies of Karl Von Ruck, that he was present at the 1882 meeting of the Berlin Physiological Society, when Dr. Koch announced that he had discovered the germ that caused tuberculosis. This is not true-however, in fact, Dr. Koch demonstrated and presented his methods and findings to Dr. Von Ruck personally, when Dr. Von Ruck visited Dr. Koch in 1883.

[41] Norwalk Daily Reflector, 17 Dec 1886, Norwalk, Ohio, page 3.

[42] Norwalk Daily Reflector, 27 May 1887, Norwalk, Ohio, page 3.

[43] Norwalk Daily Reflector, 18 Sep 1888, Norwalk, Ohio, page 3

[44] Ibid.

[45] “From Asheville North Carolina”, Norwalk Daily Reflector, 30 Oct 1888, Norwalk, Ohio, page 4.

[46] Asheville Citizen-Times, December 23, 1888, page 4.

[47] “The Key to the Sanatoria”, by O. R. McCarthy, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Volume 94, August 2001, page 413.

[48] Ibid, pages 413-414.

[49] “The History of Tuberculosis”, by Thomas M. Daniel, Respiratory Medicine, Volume 100, Issue 11, 2006, page 1862. – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095461110600401X

[50] “KOCH’S DISCOVERY: A Special Cable Dispatch to the Medical News”, Medical News, Volume LVII, No, 20, November 15, 1890. (Philadelphia, PA: Lea Brothers & Co., Publishers, 1890), page 521. https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/contagion/catalog/36-990062462610203941

[51] “A Pupil of Prof. Kochs”, The News and Observer, Charlotte, NC, November 20, 1890, page 3.

[52] “TO INVESTIGATE KOCH’S LYMPH”, Richmond Dispatch, Richmond, VA, November 21, 1890, page 6.

[53] “Results of Using Dr. Koch’s Lymph Frequently Unfavorable”, The North Carolina Intelligencer, Raleigh, NC, December 24, 1888, page 1.

[54] Ibid.

[55] “LYMPH FOR CONSUMPTIVES- Dr. Von Ruck Home From Berlin”, Asheville Daily Citizen, December 24, 1890, page 2.

[56] “Change of Base”, Asheville Democrat, February 11, 1892, page 1.

[57] “New Sanitarium”, Asheville Citizen-Times, April 20, 1892, page 1.

[58] Ibid.

[59] “BELMONT’S NEW MANAGER”, Asheville Weekly Citizen, June 16, 1892, page 5.

[60] “THE BELMONT BURNED”, Asheville Citizen-Times, August 25, 1892, page 1.

[61] “THE WINYAH”, Asheville Citizen-Times, October 17, 1892, page 4.

[62] “NEW WINYAH SANITARIUM”, Asheville Citizen-Times, January 20, 1900, page 2.

[63] “Revealing Data: Collecting Data about TB, ca. 1900”, by Susan L. Speaker- Digital Manuscripts Program of the History of Medicine Division at the National Library of Medicine. – https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2018/01/31/collecting-data-about-tuberculosis-ca-1900/

[64] Asheville Citizen-Times, January 1, 1900, page 4.

[65] 09/03/1898 (rec’d-04/24/1899) Mountain Retreat Association to Isabella P. Cotton LOTS 17 & 112 DB 106/520 & 521 Db. 1, p. 4.-Buncomne County Register of Deeds.

[66] 08/12/1899 (rec’d-09/19/1899) Eli & Laura Mustin; W. J. Slayden; and B. R. & M. S. Fakes; to Isabella P. Cotton 77 ACRES FLAT CREEK BLACK MOUNTAIN Db. 110, p. 526.-Buncomne County Register of Deeds.

[67] Asheville Citizen-Times, July 18, 1900, page 1.

[68] Asheville Citizen-Times, October 16, 1901, page 4.

[69] Journal of the Outdoor Life, Volume IX, No. 9. (September 1912). Journal of the Outdoor Life Publishing Company, page x.

[70] Ibid.

[71] A Directory of Institutions and Societies Dealing with Tuberculosis in the United States and Canada, By Lilian Brandt (New York, NY: Committee on the Prevention of Tuberculosis of the Charity Organization Society of the City of New York and the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, 1904), pg. 113.

[72] “MRS. FRANKLIN M. MALLORY KILLED WHILE ON RAILROAD TRACK”, Asheville Citizen-Times, Aug 28, 1906, page 1.

[73] The Inter Ocean, Chicago, IL, November 1, 1903, page 18.

[74] Info from: The Cyclopædia of Fraternities; a compilation of existing authentic information and the results of original investigation as to … more than six hundred secret societies in the United States, edited by Albert Clark Stevens. (New York city, Paterson, N.J.: Hamilton Printing and Publishing Company, 1899), pages 187-188.

[75] Ibid, page 188.

[76] 07/16/1904 (rec’d-07/23/1904) Wallace K & Emma P Harrison to the Fellowship Association of the Royal League 50 ACRES SWANNANOA RIVER Db. 133 page 507. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[77] “Corporations”, Biennial Report of the Secretary of State of the State of Illinois, (Springfield, IL: Illinois State Journal Co., 1905) , page 53.

[78] 09/28/1903 (rec’d-10/21/1903) John & Ellen Gragg to Wallace K. & Isabella P. Harrison 520 ACRES SWANNANOA RIVER Db. 130 page 401. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[79] Chicago Star, May 31, 1906, Chicago, Illinois, page 1.

[80] Racine Daily Journal, August 16, 1905, Racine, Wisconsin, page 8.

[81] Traverse City Evening Record, August 5, 1905, Traverse City, MI, page 1

[82] 06/27/1905 HARRISON MOUNTAIN AIR SANATORIUM, INC. Db. C002, page 292. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[83] Chicago Star, May 31, 1906, Chicago, Illinois, page 1.

[84] A Tuberculosis Directory 1911, Volume 1, National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, 1911, page 54.

[85] Ibid.

[86] “FOR INVALID NURSES”, Greensboro Daily News, Greensboro, NC, September 11, 1911, page 5.

[87] Ibid.

[88] “Dunnwyche -NCNA’s Home For Tubercular Nurses”, by Phoebe Ann Pollitt PhD, Associate Professor., Tar Heel Nurse. Volume 80, No. 1, 2018.

[89] 02/24/1917 Harrison Mountain Air Sanatorium to Cragmont Sanatorium (INC) CHANGE Db. C004, page 315. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[90] “HOSPITAL DESTROYED AT BLACK MOUNTAIN”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 16, 1920, page 3.

[91] “WILL REBUILD ROYAL LEAGUE SANITARIUM”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 19, 1920, page 16.

[92] “WORK ON ROYAL LEAGUE SANITARIUM TO START”, Asheville Times, May 11, 1920, page 12.

[93] Hospitals, Sanatoriums, State and Charitable Institutions of the United States and Canada, American Medical Association, 1922, page 86.

[94] “Why A Fraternal Sanatorium”, The Fraternal Monitor, Volume 39, Research & Review Service of America, Incorporated, 1928, page 27.

[95] Ibid.

[96] Ibid.

[97] The Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, NC, June 3, 1933, page 10.

[98] “DR. I. J. ARCHER TAKEN BY DEATH-RITES WEDNESDAY”, Asheville Citizen-Times, February 20, 1945, page 6.

[99] “PRELIMINARY CERTIFICATE OF DISSOLUTION”, Asheville Times, July 14, 1945, page 7.

[100] “Cragmont Bought By Baptists”, Asheville Citizen-Times, November 28, 1945, page 1.

[101] Asheville Times, July 16, 1947, page 2.

[102] Asheville Citizen-Times, August 14, 1955, page 40.

[103] 06/13/1958 Royal League of Illinois to S. A. & Mozelle Spencer BLK MTN TWP, Db. 800, page 424. -Buncombe Count Register of Deeds.

[104] 09/15/1958 S. A. & Mozelle Spencer to Trustees-WNC A. M. E. Zion Conference BLK MTN TWP, Db. 804, page. 209. – Buncombe Count Register of Deeds.

[105] Winston Salem Journal, Winston-Salem, NC, August 9, 1959, page 29. “It opened June 29th…”.

[106] The Salisbury Post, Salisbury, NC, January 24, 1960, page 29.

[107] Asheville Times, July 16, 1947, page 1.