by Dale Wayne Slusser

A small unassuming log cabin, which sits on a bluff just above the John B. Lewis soccer fields in East Asheville, and which is now sadly in need of restoration, is famously known as “The Thomas Wolfe Cabin”, although Thomas Wolfe never owned it, and only lodged there for a few months during the summer of 1937. Architecturally, the cabin represents and is a product of the enduring legacy of the “log cabin”, which has through a series of resurgence and revivals remained as both an iconic ymbol of America’s history, as well as a viable means of shelter. How did this unassuming log cabin, called “The Thomas Wolfe Cabin”, come to be, and what is its architectural history? And why has the cabin become so famous and taken on the moniker “The Thomas Wolfe cabin”?

The building of the Thomas Wolfe Cabin (yes, I have conceded to using its moniker) is rooted in the early 1900’s “rustic revival” architectural movement, which in the 1920’s and 1930’s also morphed into the “Log Cabin Revival” movement, which in turn was proliferated by the rise in “tourists camps” and “tourists courts” (the precursors to the modern motel). But of course, a “revival-style”, denotes a reoccurrence of an earlier architectural style. Let’s begin by first taking a brief look at the origins of the log cabin in America and Western North Carolina, and then we’ll move into its various reoccurrences in America’s architectural history.

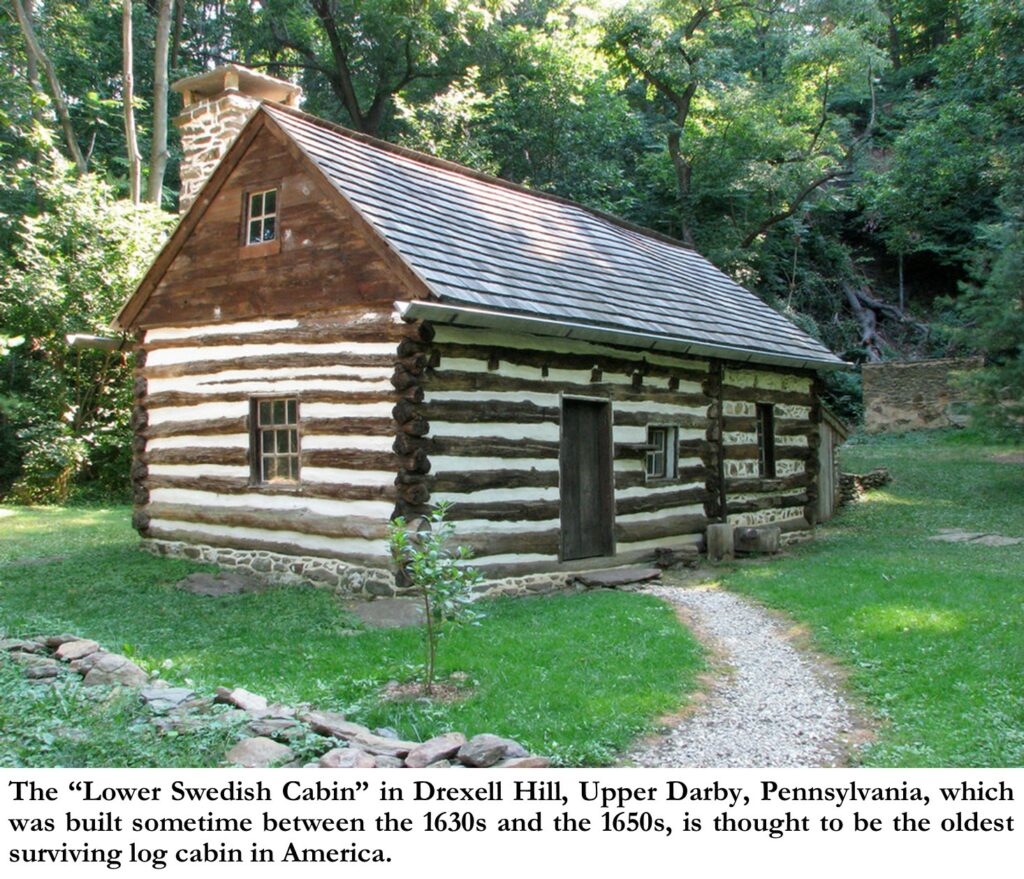

Historians have long debated the origins of log cabins in America, however modern-day consensus points to the log cabin being first brought to the new world by settlers from Sweden, where it was a traditional housing style. “Many [Swedes] settled on the Delaware and around Maryland’s tidewater region,” writes, historian Judith Flanders, “and it is here that the first contemporary references to houses built of logs appear: a court record in 1662 mentions a “loged hows”, while in 1679, a Dutchman recorded a house in what is now New Jersey, built “according to the Swedish mode”.[1] A surviving example of an early Swedish log cabin is the “Lower Swedish Cabin” in Drexell Hill, Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, which was built sometime between the 1630s and the 1650s, “and still stands, relatively unaltered, from when it was constructed hundreds of years ago.”[2] As new settlers arrived, log construction technology moved with those settlers down the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania and into the Shenandoah Valley and into the North Carolina Piedmont and Appalachian Mountains. The ingenuity of the log cabin was that the construction was extremely simple and required no more than an axe and maybe a saw. The pioneers could simply stack the logs one upon the other, and they weren’t restrained by the need for nails or spikes to keep the structure together. Plus, the log cabins could be constructed by one person in a couple of weeks.[3] “The availability of timber, the simple tools required for construction, and the possibility of individual construction”[4] caused log-cabin construction to be the number one choice of construction utilized by pioneers moving into Western North Carolina after the Revolutionary War. Even Asheville’s first courthouse, built in 1793, was said to have been a log building![5]

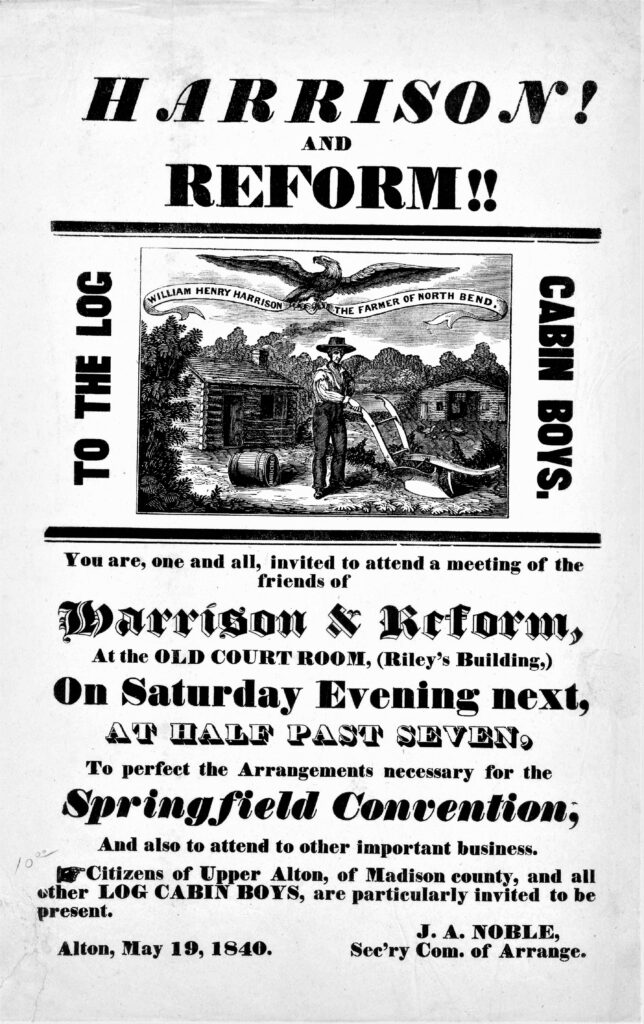

In 1840, when log cabin building in the U. S. and in Western North Carolina, was mostly being replaced by timber framed houses, politics began to shape symbolic meaning into the humble log cabin in America. In the 1840 presidential election, “William Henry Harrison’s opponents tried to downplay Harrison’s background by making fun of the fact that Harrison was born and raised in a log cabin. Instead of trying to deny his humble beginnings, Harrison shrewdly embraced it and used it to pull on the heartstrings of the common people who also lived in log cabins at that time. This resulted in Harrison’s election to Presidency by a landslide and the recognition of the log cabin as an American expression of self-sufficiency, tenacity, independence, and social mobility.[6]

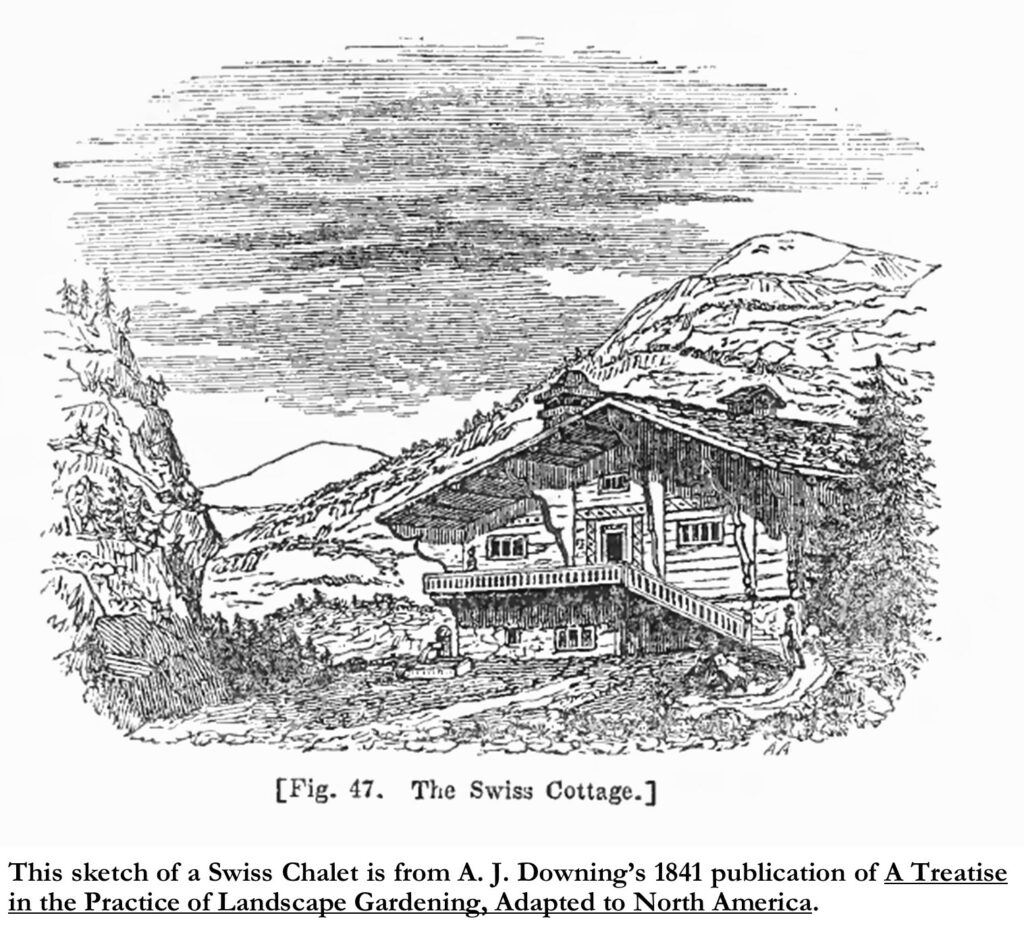

Tapping into the 1840’s growing admiration of the log cabin as a symbol of America as the “New Republic” was the rise of the Romantic Era architecture promoted by the writings, Andrew Jackson Downing. Andrew Jackson Downing, a New York landscape designer best known for his book A Treatise in the Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, published in 1841, played a substantial role in Romanticized architecture around the Hudson Valley in upstate New York. [7] An influential writer, Downing suggested that country residents abandon “the prevalent Greek Revival architecture in favor of a style more suited to the country.” Downing’s focus was on a romanticized view of rural landscapes and rural architecture, by creating naturalistic landscapes and buildings using the eye of an artist. On the heels of the success of his 1841 book, the following year, Downing published Cottage Residences, a series of designs for houses of modest size, to appeal to the “industrious and intelligent mechanics and workingmen, the bone and sinew of the land.”[8] Downing further published, The Architecture of Country Houses in 1850, just two years before his untimely death in 1852. A. J. Downing’s ideas and designs became known as the “Picturesque-style”, which was “characterized by a preoccupation with the pictorial values of architecture and landscape in combination with each other”.[9] Downing’s architectural ideas of ornamented cottages, villas, country and farmhouses, flowered into the Eastlake/Stick-style of the 1870’s and finally into the highly ornamented Queen-Anne styles of the late Victorian era.

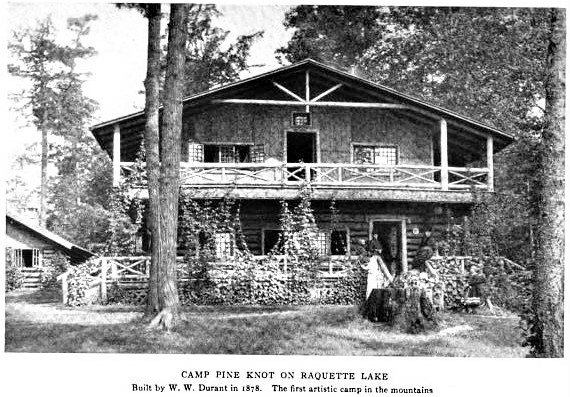

More pertinent to our topic of log cabins, is that Downing’s writings also inspired William Durant, who is considered the progenitor of the “Adirondack-Style”, also known as “The Great Camp-Style” of architecture. In 1876, William Durant’s father, Dr. Thomas Clark Durant, railroad builder, purchased large tracts of the Adirondacks in upstate New York, intent on opening and developing the Adirondacks as a summer resort. He hoped this effort would be facilitated by his rail line, the Adirondack Railway Company. Following local building styles, Dr. Durant’s earliest camp dwellings were log cabins constructed of bark-clad logs with wide, overhanging eaves. But it was Dr. Durant’s son, William West Durant (1850-1934), who formulated the hallmarks of Adirondack rustic architecture, when between 1876-77, William began to transform his father’s camp, Camp Pine Knot at Raquette Lake, into an artistic rustic retreat for wealthy vacationers. At Camp Pine Knot, William Durant combined the indigenous Adirondack log cabin and lumber camp construction; with the Picturesque ideas of “naturalistic motifs for country homes placed in wild settings”[10] and the Swiss chalet from Downing’s writings. Durant’s designs for Camp Pine Knot were the first of his “Great Camps” and would eventually become the model for “Adirondack-style Rustic Architecture”.

The Adirondack-Style architecture was characterized by the use of natural building materials like wood and stone, which could be found easily. And because the Great Camps were built in the wilderness far from sawmills and manufacturing facilities, their builders, like the pioneers of times past, most often utilized log construction that could be achieved with the use of hand tools. In fact, log construction, albeit on steroids, became the hallmark of the Adirondack-style. This is ironic, as although A. J. Downing often featured sketches of “rustic-style” benches, chairs, and arbors, all made of logs, he actually disdained log houses, often calling them “log huts”. In fact, in his preface to his publication of The Architecture of Country Houses he wrote, “So long as men are forced to dwell in log huts, and follow a hunter’s life, we must not be surprised at lynch law and the use of the bowie knife.”[11] Despite Downing’s disparaging attitude towards log houses, Durant applied Downing’s principles and elevated the “log hut” to an artistic, tasteful, and sought-after mode of habitation-that is, a nice place to live!

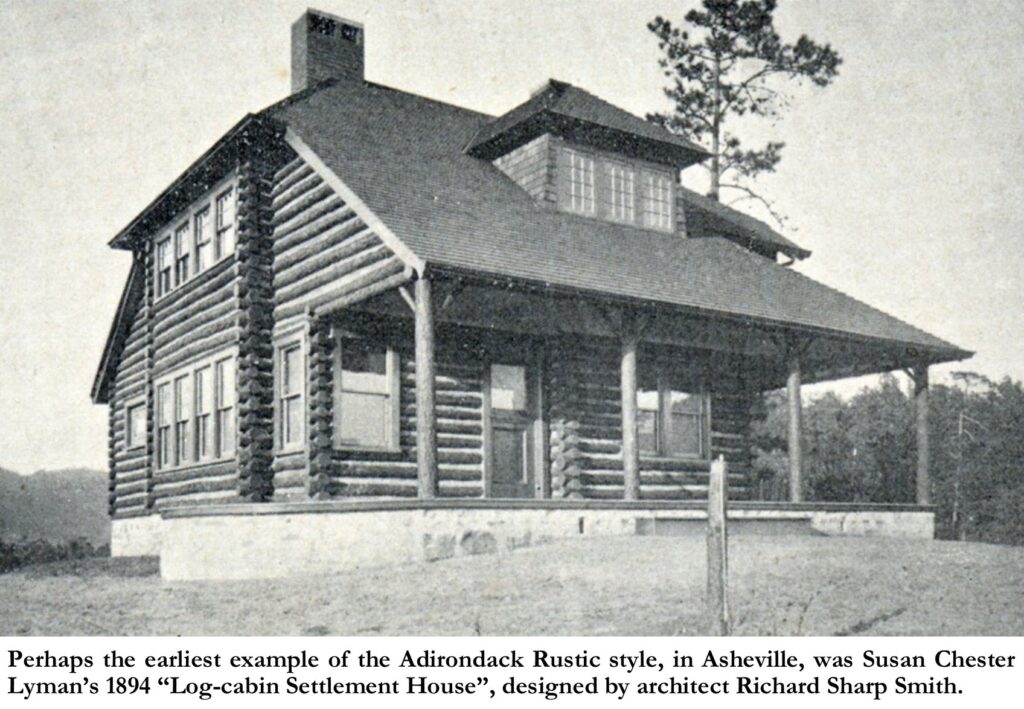

The Adirondack-style became associated with the “Great Camps” and other “Health Resorts” of the late Victorian-era, where wealthy and middle-class people could escape to the “wilderness” for rest, relaxation, respite, and/or resort. In the 1870’s, just as the Great Camps were beginning, men like Dr. J. F. E. Hardy began an active campaign to promote Asheville as a “Health Resort”, where those with ailments (especially of the lungs) could come and be healed by the “healthful” climate and fresh mountain air. The arrival of the railroad in 1880 propelled the campaign to make Asheville a premiere health resort and tourist destination. Not surprisingly, with its shared clientele and similar rugged mountain “wilderness”, the Adirondack Rustic style of architecture began to be proliferated in Asheville and Western North Carolina, by the late 1890’s. Perhaps the earliest known example of the Adirondack style, in Asheville, was Susan Chester Lyman’s 1894 “Log-cabin Settlement House”, designed by architect Richard Sharp Smith, who had just recently been sent to Asheville by his employer, Richard Morris Hunt to supervise the building of the Biltmore Estate. Lyman, a graduate of Vassar, built her “Settlement House” in the Beaverdam area of Asheville, for the purpose of providing a place for the “reviving of the weaving industry”, utilizing the weaving skills and talents of the local mountain women, to not only make their weavings available to the public, but also to give them a means of generating income. Lyman’s Settlement house was the progenitor of the craft-revival movement that led to the Allanstand Cottage Industries, Edith Vanderbilt’s Biltmore Industries and ultimately the Southern Highland Craft Guild. Richard Sharp Smith took Downing’s advice and applied the touch of the artist in designing Lyman’s “log-cabin”. Utilizing round logs, Smith essentially designed Lyman’s Settlement House as a log bungalow, with a second floor under a large sweeping truncated-side-gabled roof which covered a large front porch. Like a bungalow, the artful log cabin had a two-story side-bay and a shingled front dormer. Smith would go on to design other Adirondack Rustic-style houses in the Asheville area, such as the Connelly family lodges on the North Fork, the Calderon Carlisle lodge at Glenn Inglis, Dr. Ambler’s “Rattlesnake Lodge” and S. R. Keesler’s “Breezinook” at Montreat, NC.

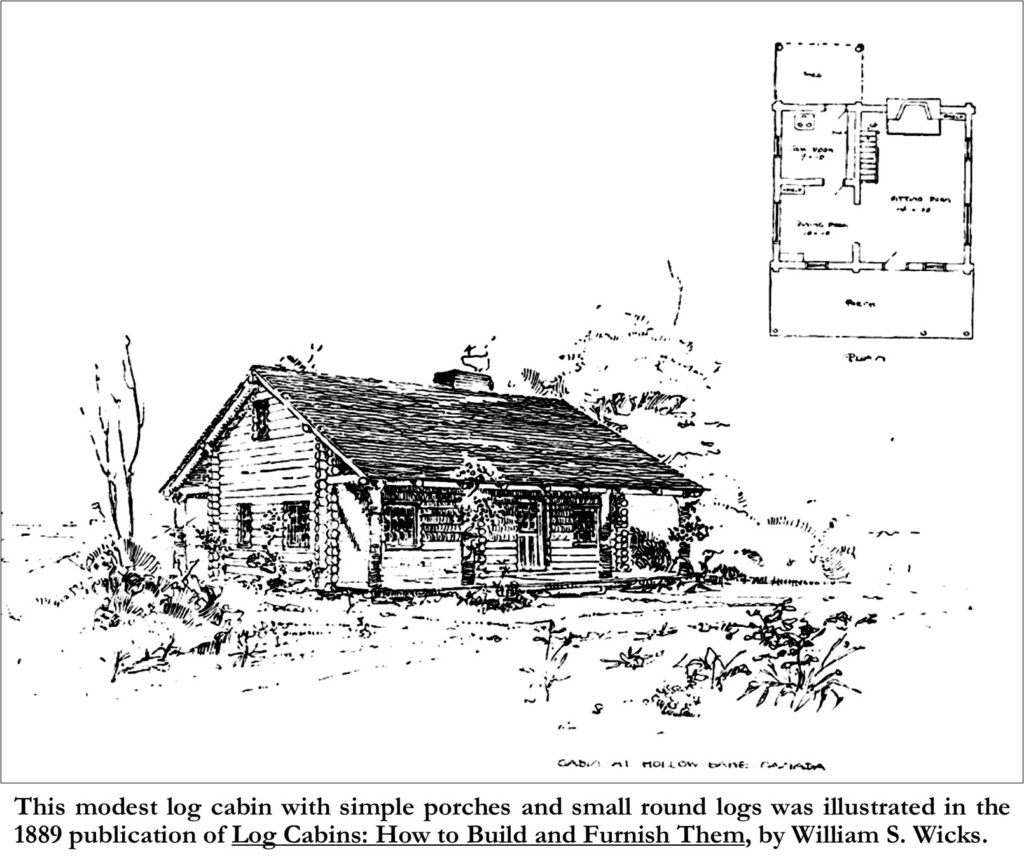

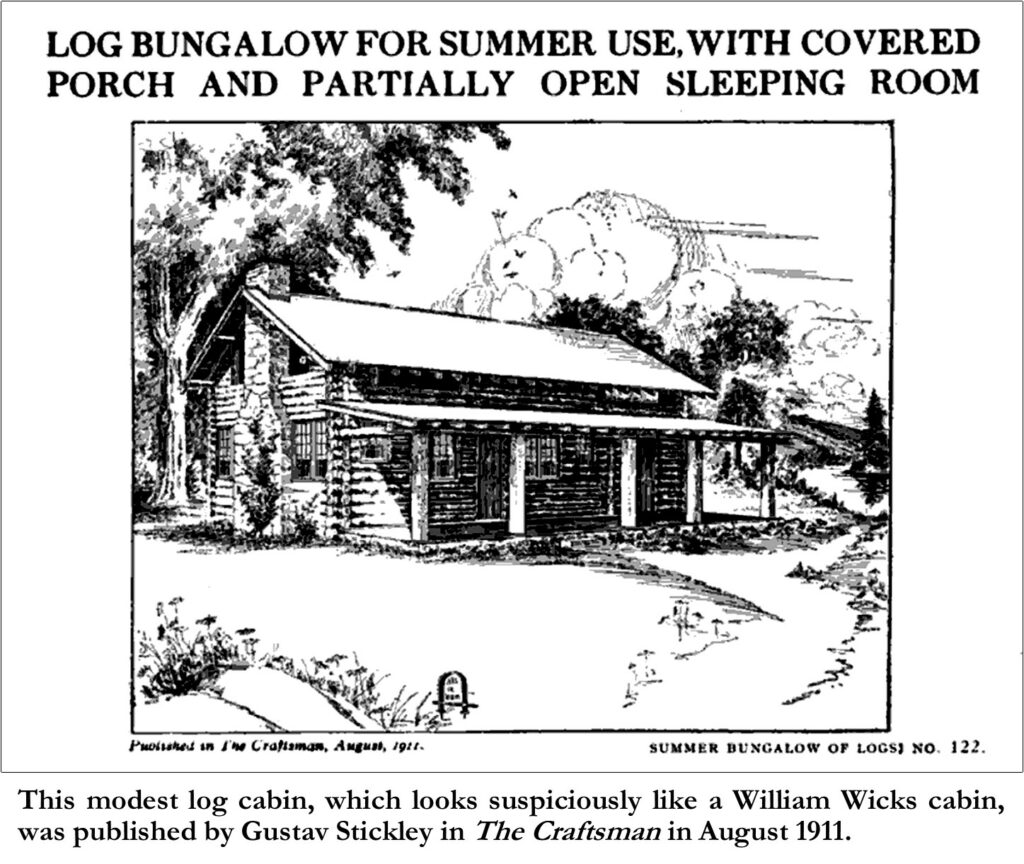

What William Durant did for the wealthy who desired a rustic escape to the wilderness in a luxury Adirondack log cabin, William S. Wicks accomplished for the middle-class and working classes with his 1889 publication of Log Cabins: How to Build and Furnish Them. Although William Wicks was an architect working in the Adirondacks, his book “instructed readers how to build a modest log cabin, not a sprawling Adirondack camp”.[12] William Wicks’ log cabins utilized smaller round logs and were of a smaller scale than the large log-lodge structures then being built in the “Great Camps” in the Adirondacks. These smaller-scale cabins soon became the norm for those desiring to build a log cabin, and in the ensuing decades, especially up to the 1930’s, one and two-room log cabins were replicated as hunting cabins, lake cabins, tourist camp cabins, tea rooms, and gift-shops and restaurants.

As the twentieth-century dawned, the American Arts & Crafts movement was developing. The American Arts & Crafts movement was an off-shoot of the 19th-century British Arts & Crafts movement, however, although the American Arts & Crafts movement touted the same principles of elevating and integrating the work of the designers and craftsmen, the promoters of the American Arts & Crafts Movement, such as Gustav Stickley and Elbert Hubbard sought to adapt those principles to life in America. While practitioners of the movement in America also believed that a strong connection between the artist and their work was the key to human fulfillment, they largely overlooked the socialist politics of their neighbors across the Atlantic. As a whole, American craftsmen embraced the modern technology of machines, believing that it took a marriage of design and industry to produce beautiful objects for the majority of people.”[13] “Stickley, already a veteran of the furniture business, formed Craftsman Workshops in upstate New York in 1903, bringing together a talented guild of designers, cabinet makers, and metal and leather workers. He began publishing a monthly magazine called The Craftsman, a how-to manual for living the Arts and Crafts style, and pledged to achieve “the union in one person of the designer and the workman.”[14] Although a furniture maker, Stickley also was a promoter of the Arts & Crafts application to architecture and can be credited with popularizing the “bungalow” specifically through the “Craftsman Homes” section in his monthly Craftsman magazine, which included images, plans, and original designs by architects Greene & Greene, among others. Between 1907 and 1925, the bungalow was one of the most sought-after home designs.[15]

Gustav Stickley incorporated into his promotion of the Arts & Crafts movement the American “Log-cabin myth”. By1907, he was promoting the building of log cabins as Craftsman-style bungalows. In fact, in 1908, Gustave Stickley built “a low, roomy house built of logs”,[16] as the first building on his Craftsman Farms campus in upstate New York. I believe, besides adopting the log-cabin myth, Stickley was also influenced (consciously or unconsciously) by the ruggedness and Americanness of the Adirondack-Rustic style, which was nearby, and saw both the Adirondack-style and the log cabin as true American interpretations of the ideals of the Arts & Crafts Movement.

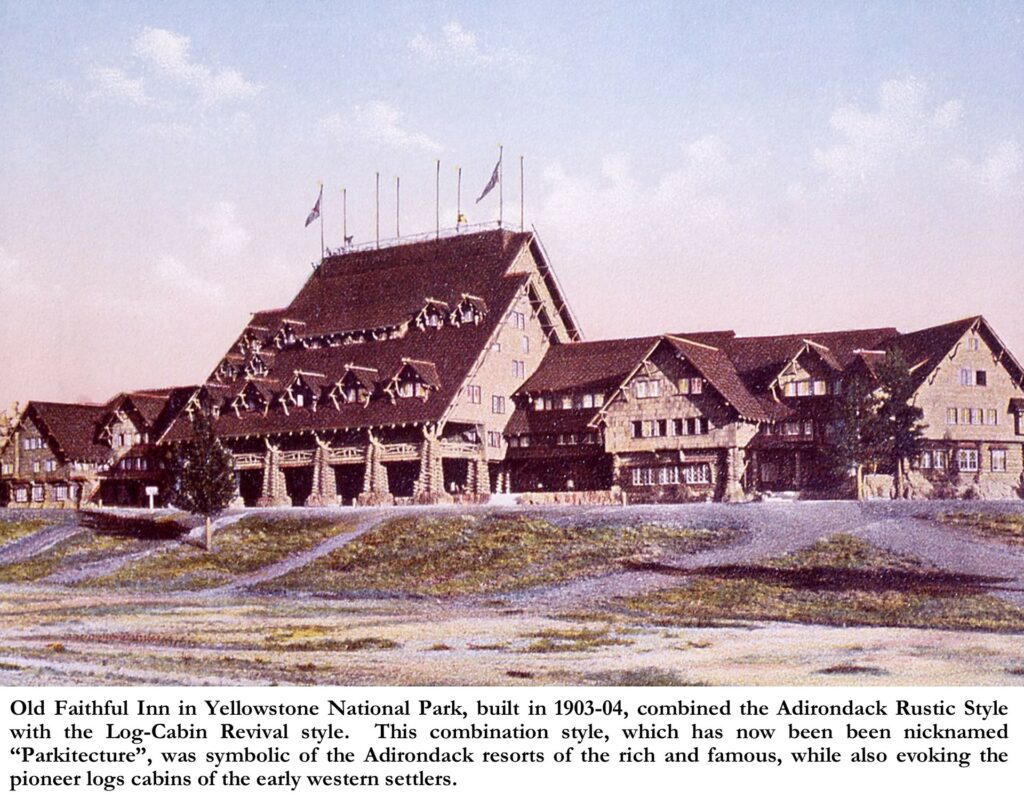

Another factor that brought a renewed interest in the log cabin during the first three decades of the twentieth century was the rise of the “National Park”. By the Act of March 1, 1872, Congress established Yellowstone National Park in the Territories of Montana and Wyoming “as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people” and placed it “under exclusive control of the Secretary of the Interior.” On August 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the act creating the National Park Service, a new federal bureau in the Department of the Interior responsible for protecting the 35 national parks and monuments then managed by the department and those yet to be established.[17] Included in the 1916 list of parks was the Pisgah Forest, which Edith Vanderbilt sold to the National Government in 1914, following the death of her husband George W. Vanderbilt. The Pisgah Forest had been part of Vanderbilt’s vast Biltmore Estate. The first decades of the National Park Service adopted the log cabin and Adirondack-style for their park structures, such as Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone National Park, built in 1903-04. “Infused with native materials, natural whole logs, and built by hand (or meant to look as if it was), these buildings took on their own style, and the style became known as “Parkitecture”.[18]

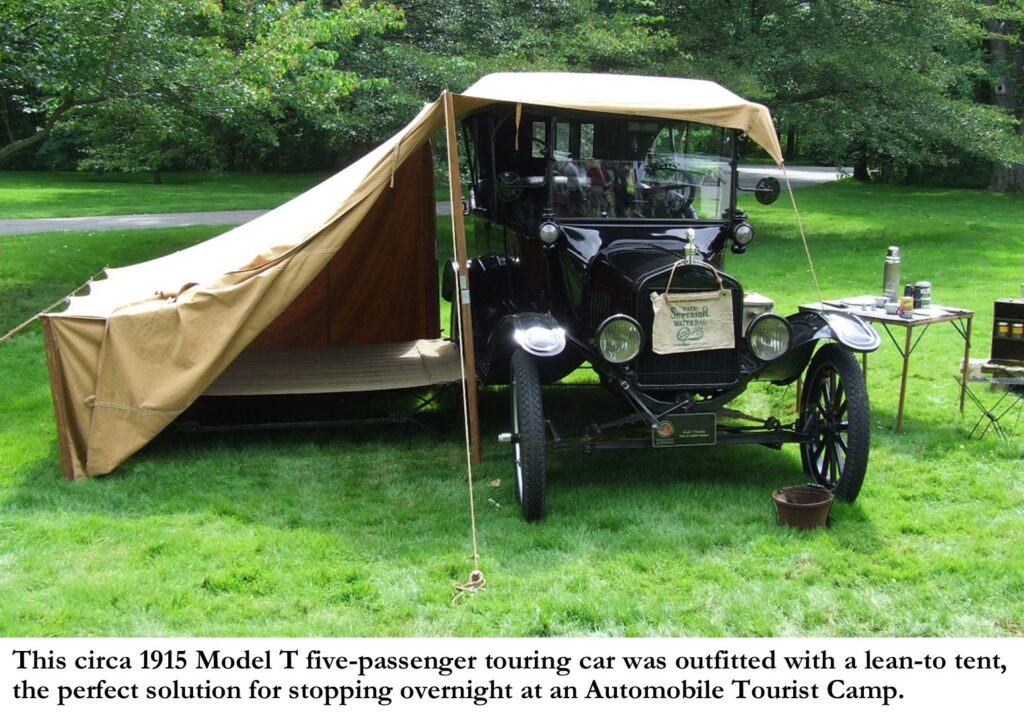

But of all the societal influences that may have led to the building of the Thomas Wolfe Cabin, the two most direct influences were no doubt, the proliferation of the automobile, and “the vacation”. “Ownership of motorcars rose from 0.5 million in 1910 to more than 8 million in 1920 to 26.5 million in 1925, and the declining cost of the automobile meant that middleclass Americans were more able to afford one.”[19] Now, the rising middleclass not only had affordable places to escape to (National Parks) on their “vacations”, but with the affordable automobile, they now had a viable means of getting there and back.

By the 1920’s and 1930’s, the rise of the National Parks in conjunction with the proliferation of the automobile to the middle-class, also led to the creation of the “tourist camp”, an affordable and desirable accommodation for those who needed a temporary place of lodging on their vacation or their journey to the “wilderness”. The early tourist camps were just as their name implies, little more than a campground where “tourists” could choose a campsite to pitch a tent or park their car (to sleep in). In turn, the camp would usually provide toilet and bathing facilities, and sometimes recreational opportunities. Asheville’s first tourist camp, was a public municipal camp, established by the city in 1922 on the Old Waterworks property on the Swannanoa River, on land just below the site of the future Thomas Wolfe Cabin. In conjunction with the Asheville Tourist Camp, a recreational park and swimming pool, were soon added as additional incentives to draw tourists into the camp. In 1924, a dam was erected at the site of the former waterworks, next to the tourist camp, and a lake was formed as another added feature (the lake was called Lake Craig).[20] However, by 1926 the city had decided that the tourist camp was not as profitable as had been expected and so they closed the camp and turned the area into a picnic grounds and operated the entire camp as a municipal recreation park only.[21]

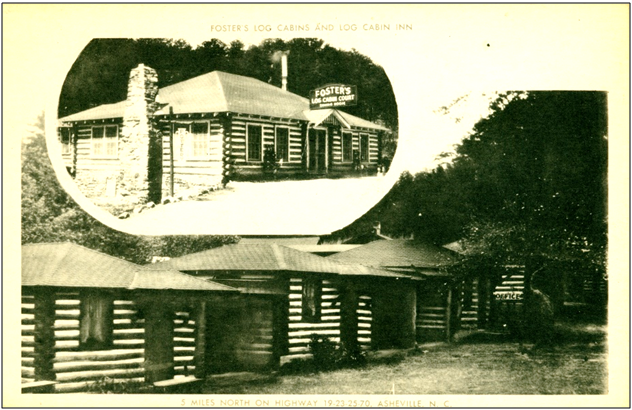

Alison Hoagland, author of The Log Cabin: An American Icon, writes that at first the municipal “tourist camps” across the U. S. were free of charge, but that “once campgrounds proved popular and began to charge fees, entrepreneurs entered the market.”[22] Soon the tents at private tourist camps gave way to cabins, often laid out around an open courtyard, hence “tourist camps” soon became known as “tourist courts”. The “cabins” at tourist courts were often built of logs or simulated logs (slabs of half round timber used to simulate log construction), for as author Hoagland further tells us, “Even the name-cabin- led logically to a log cabin, the familiar domestic icon.”[23] This evolution from tourist camps to tourist courts, not only occurred across America in the 1920’s and 1930’s, but locally the evolution took the same form and had relatively the same timeline. In fact, I suspect that the 1926 closing of the Asheville Tourist Camp may have jump-started the trend in Asheville and its surrounding area, as within five years, a number of private tourist camps began sprouting up around Asheville. From 1930-1933, several private tourist camps opened up north, south, west, and east of Asheville along the major travel routes, such as the Asheville-Henderson Highway (north-south), the Asheville Black Mountain Highway (east), the Charlotte Highway (southeast), the Marshal Highway (northeast to Tennessee), the Pisgah Highway (southwest), and the Smoky Park Highway (west). A 1932 newspaper article in the Asheville Citizen-Times reporting about rise of the local tourist camps, reported that there were then “around a dozen such camps in the immediate vicinity of Asheville”.[24] Four of the dozen tourist camps mentioned, were not only among those closest to Asheville, but they also had the distinction of using log cabins for their buildings.

The first two of the four camps to open were “Foster’s Log Cabin Court” (330 Weaverville Rd), and “The Pines” (346 Weaverville Rd). Located adjacent to each other, north of Asheville on the Weaverville Highway, both were opened in 1931.[25] Zebulon H. and Audrey Foster, both Buncombe County natives, purchased two lots in Pine Burr Park in 1920.[26] Zebulon Foster (1881-1941) worked in the cleaning business in Asheville when he met Audrey Smith (1894-1978), a nurse at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Roye Cottage Sanitarium. Residing in the Montford neighborhood at the time, the couple bought the property, approximately five miles north of Asheville on the Weaverville Highway because of their desire to return to a more rural setting. The Weaverville Highway which was part of the former Dixie Highway which connected the Midwest with Florida. The heavily traveled highway provided a steady stream of potential guests, who had few other options for overnight accommodations on this section of road. At some point in the late 1920s, a passing traveler asked to stop for the night and camp under the pines. The visitor’s compliments about the beauty and comfort of the site planted the idea with the Fosters that the property could become a regular tourist camp. Around 1931, the Fosters hired Bill Parker of Reems Creek to build the first set of seven cottages with little porches. Arranged in a line, the one-room cabins were constructed of pine logs. After the success of the first season, the Fosters erected six more one-room cabins that formed a second line. Around 1932, Zeb Foster sold his cleaning business in Asheville to assist with managing the tourist court, which they called Foster’s Log Cabin Court. During the mid-1930s, the Fosters added a few more cabins, including several larger units, a laundry, a public bath house to replace the outhouses, and the dining lodge, which was completed in 1937.[27] All these cabins, including the dining lodge were built using small “pole-logs” with corner saddle-notches, and chinking in between the logs. This use of smaller diameter pole-logs with pronounced chinking would become the standard type of log cabin being built in this area during the 1920’s through the 1940’s.

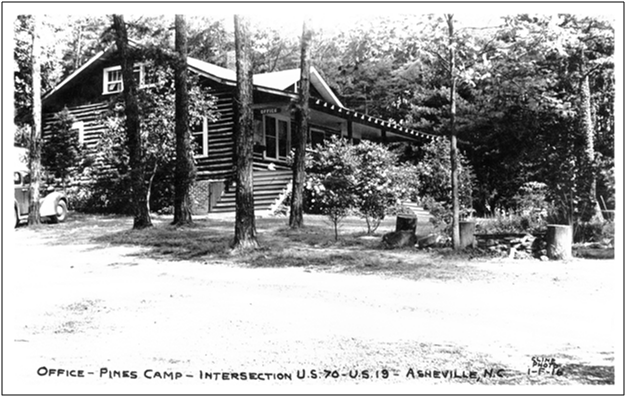

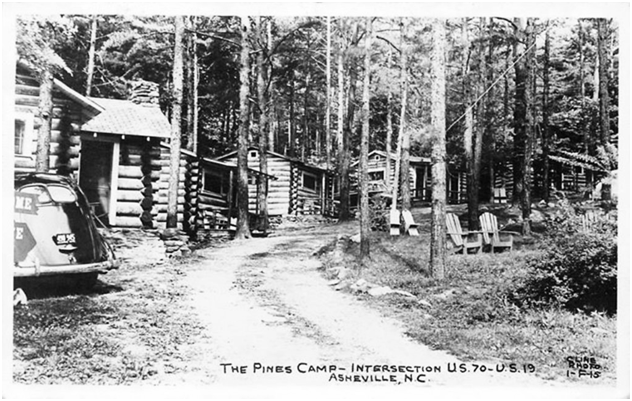

Immediately to the north (adjacent to) of Foster’s Log Cabin Court , “The Pines” was built by and operated by William W. and Ida Pruett. In 1922, the Pruett’s bought “lot 29-1/2” in Pine Burr Park from Marian A. Putnam.[28] At the time William Pruett had just began working for Louis Carr Lumber Company, near Brevard. Soon after purchasing the property, the Pruetts built a five-room “log bungalow” on their new lot.[29] By 1924, the Pruetts were spending more time in Brevard, and so Ida began advertising their Pine Burr Park “log bungalow” for rent: “LOG BUNGALOW on Weaverville Road. 5 rooms and bath. Completely furnished. City water and lights. Reasonable rent. No sick. Mrs. W. W. Pruett, Pisgah Forest.”[30] The Pruett’s “log bungalow” was just that, a one-story log cabin built in the bungalow style with small pole-logs and chinking. The Pruett’s continued advertising the bungalow for rent on into 1930. But by 1933, they had decided to expand their rental options, by building several small log cabins on the adjacent lot to the south, which they had purchased in 1925.[31] No doubt they got their idea from the Foster’s Log Cabin Camp, next door, which had opened in 1931. The log cabins that the Pruetts built were small one-room cabins with a small porch overhang at each entrance door. Ida Pruett named their new tourist camp, “The Pines Cabins”.

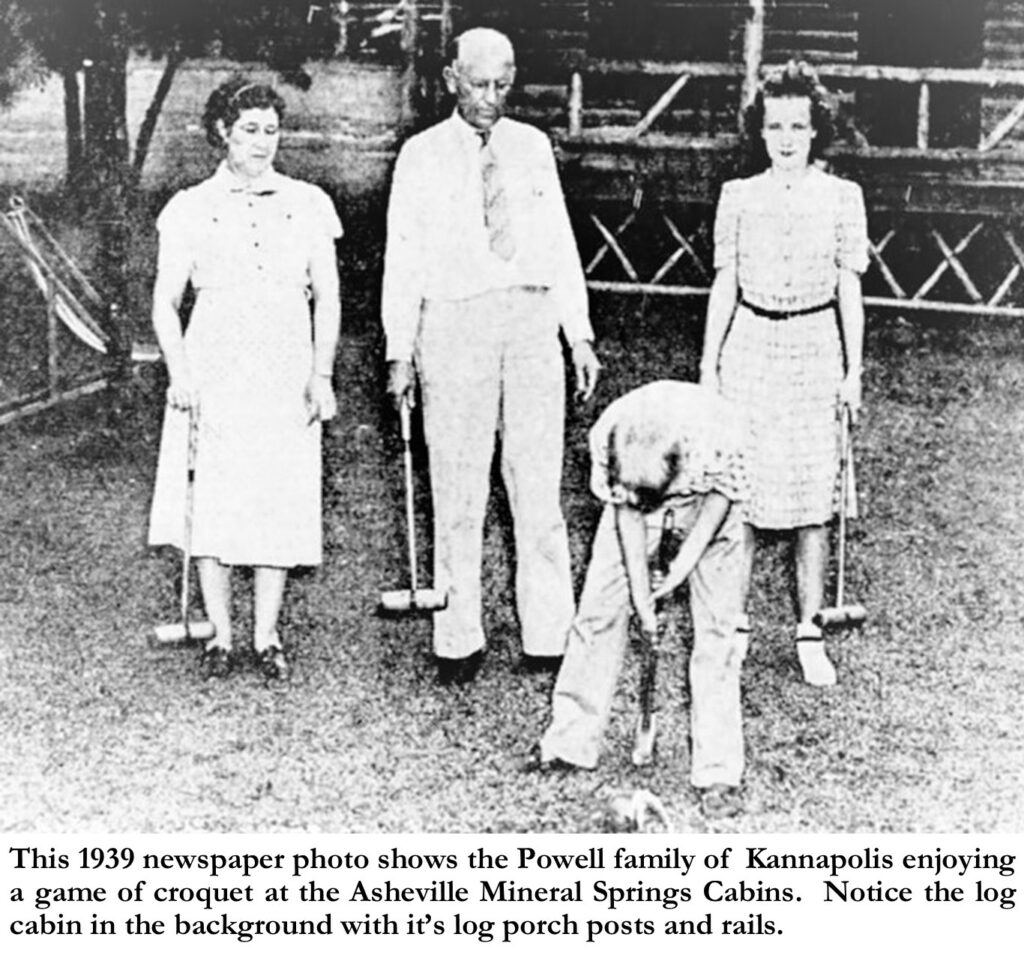

Shortly after the opening of the Beaucatcher Tunnel in 1929, Wallace Wright, whose family homestead just happened to adjoin the new Highway 20 (Tunnel Road) just after it emerged from the eastside of the Tunnel, decided to open his own tourist camp. Using the wooded site’s natural mineral springs as a draw, Wright constructed ten log cabins surrounding the spring, and in 1932 opened as “The Asheville Mineral Springs Cabins”. The cabins were typical tourist camp cabins, built with small pole-logs with chinking in between the logs. A 1939 newspaper photo shows that the cabins also had porches with log posts and rails. The Asheville Mineral Springs Cabins were operated by the Wrights until 1964, at which time the property was sold to developer Perry Alexander as the site of the Tunnel Road Shopping Center (Innsbruck Mall).

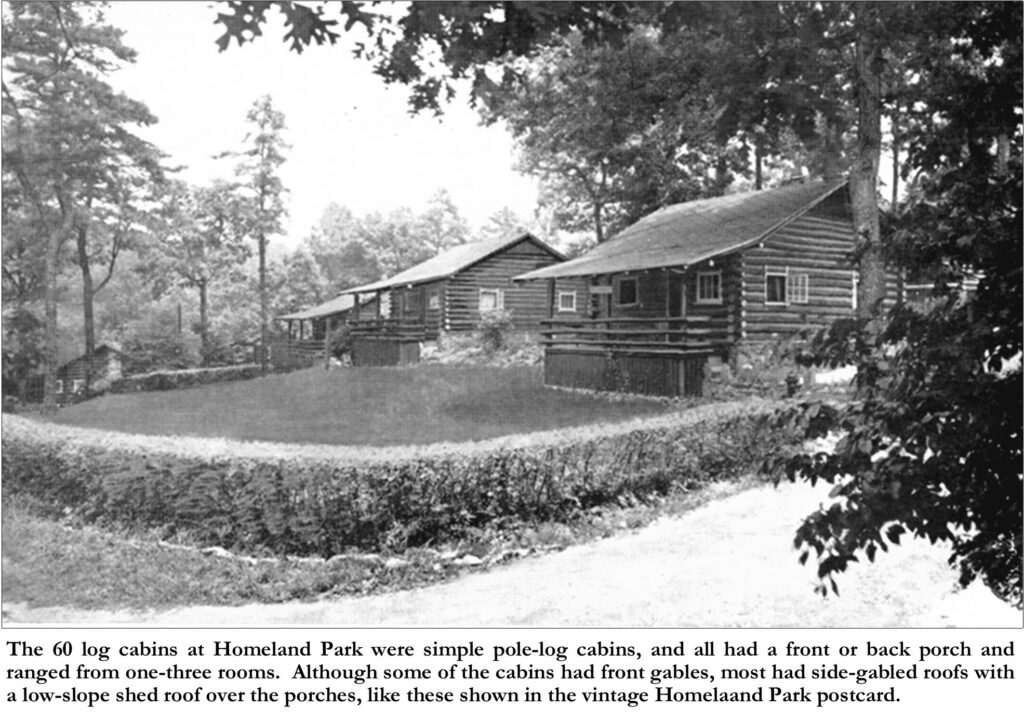

The fourth closest tourist camp to be established near the Thomas Wolfe Cabin was “Homeland Park.” In 1932, developer Eugene G. Hester and his second wife, Elizabeth B. Hester, along with their business partner Hubert C. Jarvis formed Homeland Park, Inc. Hester was a seasoned developer having been the co-developer (with Jake Childs) of the second Kenilworth Inn and the surrounding Kenilworth Park subdivision, beginning around 1913. Hester and Jarvis had a full-service vision of capitalizing on Asheville’s burgeoning tourist industry, as their corporation’s purpose was not only to build, buy, sell, or lease real estate, but also to “manufacture, buy, and sell furniture and fixtures”, “to buy, sell, trade and deal in, wholesale and retail groceries, provisions…general merchandise”, and “to make and sell novelties made of wood, leather, cloth, wire, and other metals”.[32] Homeland Park delivered on these services by not only providing lodging but also providing dining facilities, gift shop, and general merchandise, as well as providing recreational facilities. But the primary draw to Homeland Park was its 30 log cabins, which in 1935 expanded to over 60 log cabins, all equipped “with showers, tubs and toilets”.[33] These simple pole-log cabins all had a front or back porch and ranged from one to three rooms. Although some had front gables, most had side-gabled roofs with a low-slope shed roof over the porches.

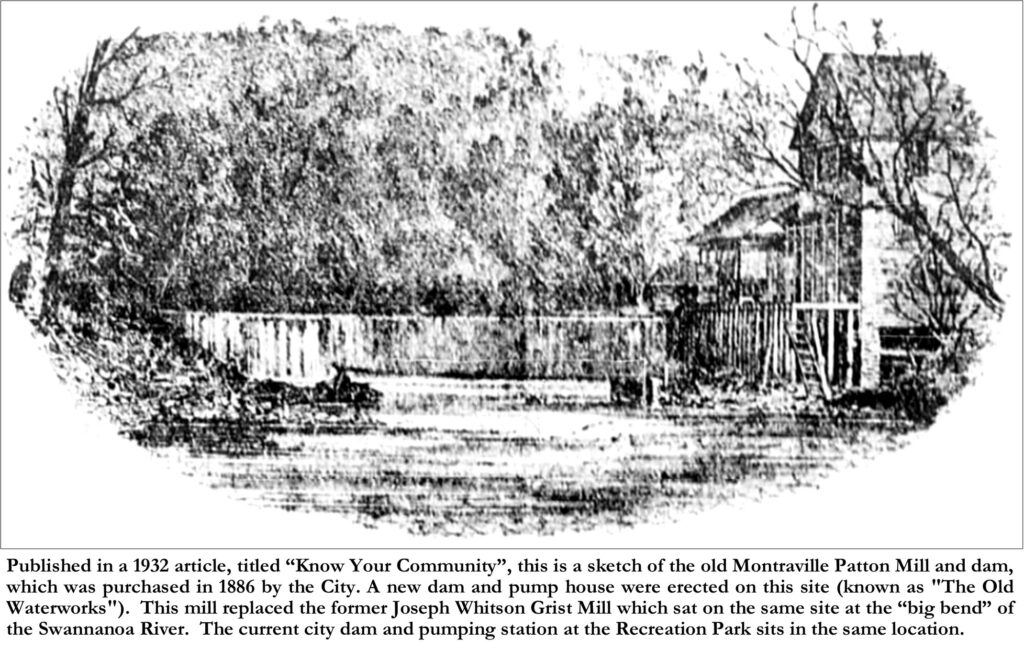

Into this frenzy of log-cabin building during the 1920’s and 1930’s came local cartoonist Max Whitson (Edward Maxwell Whitson). Max’s great-great grandfather, William Whitson, was one of the earliest settlers of Buncombe County, settling on 400 acres along “Rosses Creek” in 1795[34]. William Whitson, in 1806 decided to move west to take up grants in Maury County, TN, so he sold his farm (all of what is now S. Tunnel Road) to a new settler, James Patton! Unfortunately, William died enroute to Tennessee. Only one son, Joseph Whitson, remained in Buncombe County. In 1814, Joseph purchased a 180-acre farm from Col. John Patton, on both sides of the Swannanoa River at the “Big Bend”.[35] Joseph Whitson either built or moved into a log cabin on the property, and he would also establish a grist mill and saw mill as well. In 1854, Joseph sold 25 acres of his property, including the Grist Mill at the “big bend” to the Buncombe Manufacturing Company. This piece of the Whitson property would later be sold to Montraville Patton and known as “Patton’s Mill”. This mill was purchased in 1886 by the City and a dam and pump house were erected (this was later known as “The Old Waterworks”)-the water from there was pumped over Beaucatcher to a standpipe reservoir. It was on this property that the city, in 1922, opened the Asheville Tourist Camp/ Recreation Park.

The remainder of the Joseph Whitson property (east and south of the “Big Bend”) including the family’s log home descended to his son, Dr. George W. Whitson. In his retirement years, around the turn of the twentieth-century, Dr. Whitson built a “modern” two-story house to replace the original Joseph Whitson log-house.[36] The house and property, which remains at 1010 Oteen Church Road, was after Dr. Whitson’s death in 1906 and his wife’s death in 1920, continued to be occupied by Dr. Whitson’s four unmarried children; son Henry, and daughters, Sallie, Jennie, Mary and Hattie. This remaining Whitson land, in the 1920’s, was mostly on the hill above Azalea Road east of the Tourist Camp/ Recreation Park.

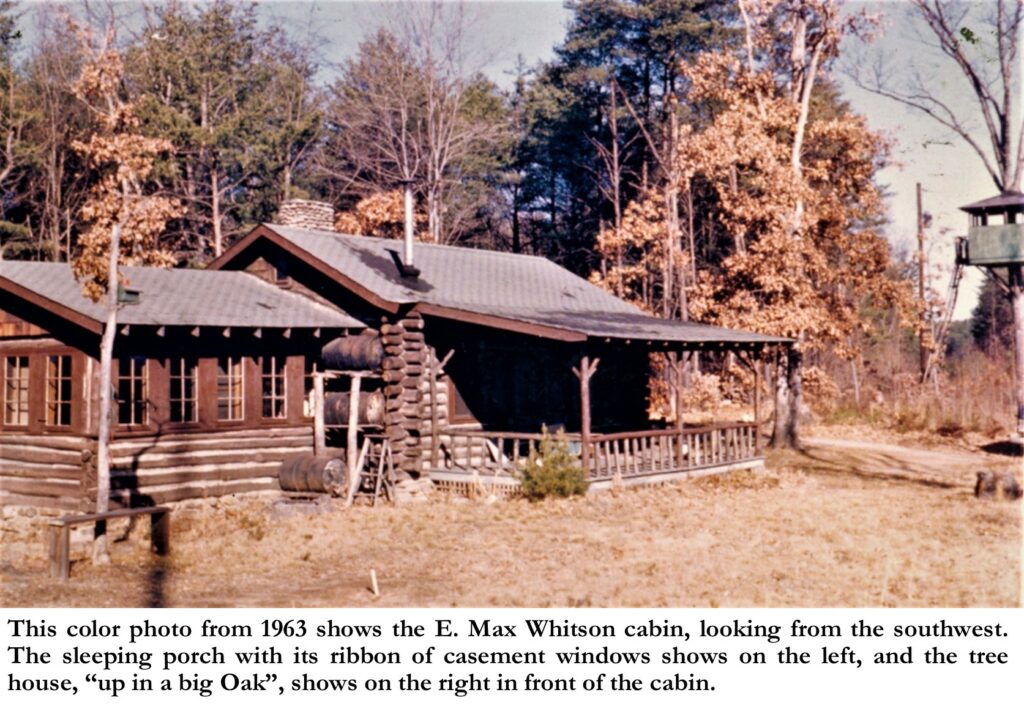

It was on this Whitson land (occupied by his aunts & uncles) that Max Whitson chose to build his retreat cabin in 1930. Max was then 35 years old, unmarried, and living in his boyhood home at 176 E. Chestnut Street in downtown Asheville, with his mother, sister Maude, and his uncle James Keith (his mother’s brother).[37] I have seen references saying that Max built his log cabin in 1924 or 1925, however I suspect that it was not built until after 1930, which is when the estate of George W. Whitson was finally settled by court appointed commissioners who divided the property and assigned each division to one or multiple heirs. The cabin was built on “Tract #6 of Tract #3”, a 9 acre tract that was assigned to Max; to Max’s mother Ida Whitson (his father had passed away in 1929); his brother William K. Whitson; and his sister Maude Whitson.[38] The lot assignments were allotted “according to their respective rights and interests” and “allotted jointly as prayed for by certain of the petitioners”, so in that respect it is possible that the cabin could have been on the tract prior to its assignment. However, the first mention of the cabin in the newspapers was not until 1932, when it was reported: “WHEN MAX WHITSON gets tired of drawing funny folks he shuts up shop and goes out to his “garden of eat’in” in the big woods above Lake Craig. Cedar Cliff cabin is his sanctuary.”[39] The article goes on to describe the cabin: “It is completely equipped with everything that makes for peace and comfort, from living room to shower bath and is hid away in the heart of the wilderness where no one ever intrudes.”[40] Other features of the cabin, as reported, included a Gold Fish pond, a “30-foot swing” which “sways invitingly between two trees,” and a tree house “up in a big Oak”. The writer describes the tree house as a “furnished bungalow with a front porch which is reached by a sort of ship’s companionway with handrails-very steep”.[41]

Architecturally, Max Whitson’s cabin was built of small pole-logs with chinking in between the logs. Very like the cabins then being built in the surrounding tourist camps, the cabin was one story, with a side-gabled main roof and low-pitched shed roof over the rear kitchen and bath and another low-pitched shed roof over a front porch (which extended across the front of the cabin). The cabin had three rooms in its main section, a large living room, a small kitchen and a full bath. A “sleeping porch” with low log walls with screened windows above was built on the west side of cabin. The scale and size of the Whitson cabin is like those built on the other side of the hill at Homeland Park, although the Whitson cabin does predate the Homeland Park cabins by at least two years.

During the 1930’s Max Whitson and his siblings used their cabin both as a retreat as well as a place for entertaining, and for club meetings (such as the Asheville Exchange Club and the DeMolays-a leadership youth club). On June 19, 1935, it was reported that the members of the Asheville Exchange Club and their wives, held a picnic “at the cabin of Dr. W. K. Whitson, near Azalea”.[42] I suspect that although the siblings jointly owned the tract and jointly used the cabin, that Max Whitson was the builder of the cabin, as in that same month, June of 1935, the siblings sold their “two-thirds undivided” interest in the 9 acre tract to Max Whitson, giving him sole ownership of the cabin.

Max Whitson and his small cabin would have fallen into obscurity, had it not been for the Summer of 1947. Hometown author, Thomas Wolfe, whose father was Asheville’s “Monument” gravestone carver and supplier, and whose mother was the proprietor of the “Old Kentucky Home” boarding house on Spruce Street, decided to return home to Asheville in 1937. Thomas Wolfe had not been home since the 1929 publication of his novel, Look Homeward Angel, a story of a fictionalized mountain town called “Altamont” whose characters (good and bad) were obviously based on Wolfe’s Asheville family and residents. In fact, the descriptions and names of the novel’s characters were so thinly disguised that hometown animosity rose against Wolfe and was so strong that he feared returning home to an angry mob! But by 1937, the hometown animosity had waned, and had been mostly replaced with pride for the hometown boy who had made the bigtime! A famous New York City writer! Wolfe arrived in Asheville in May of 1937, but alas decided to only stay for a few days, before returning to New York City. However, he felt so welcomed that he decided to return to Asheville for the summer, and so before returning to New York (to wrap up some business) he sought out Max Whitson, a former classmate (from the North State Fitting School). “Tom heard I had a small cabin up near the Recreation park and wanted to rent it for the summer”, recalled Whitson in 1971.[43] Max took him up to see the cabin, and Wolfe was so pleased with it that he immediately wrote a check for the first month’s rent.[44] Wolfe returned to New York, where he later received a letter in June from Max Whitson informing him that Whitson had “put the cabin in good shape, waxed the floors, fixed up the road that leads to the place, and has put in some new furniture, and that everything is now comfortable and ready!”[45]

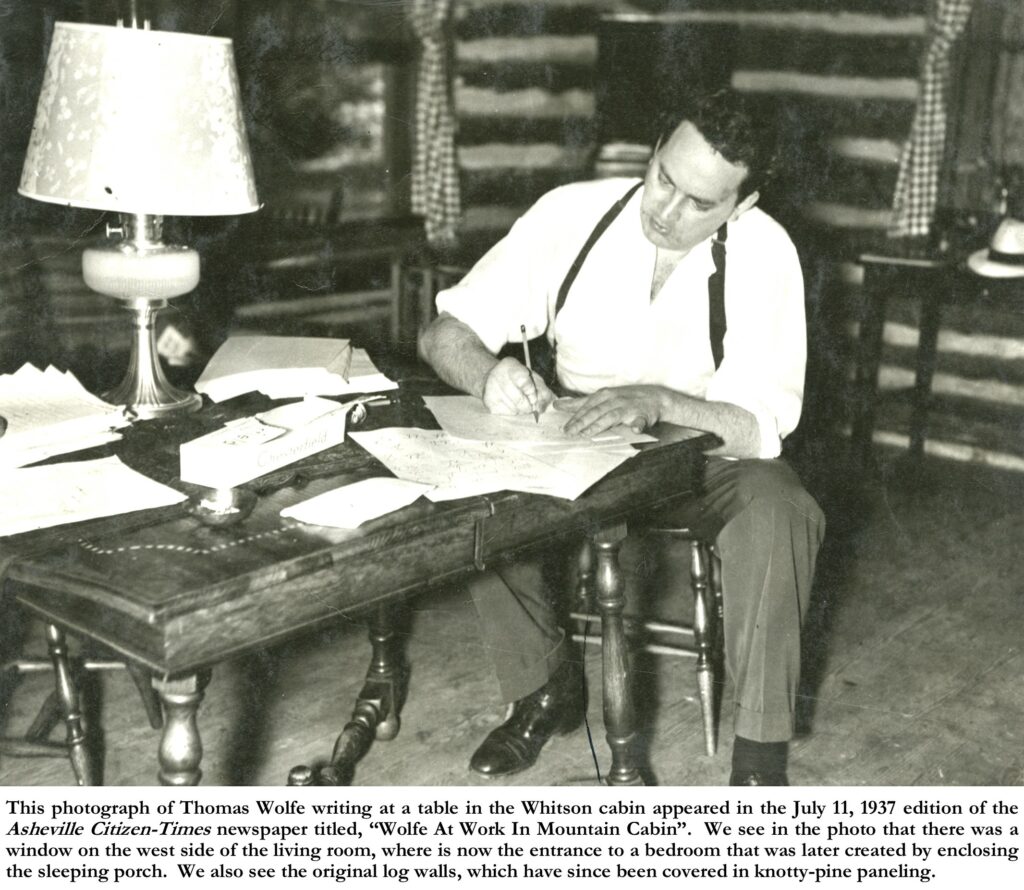

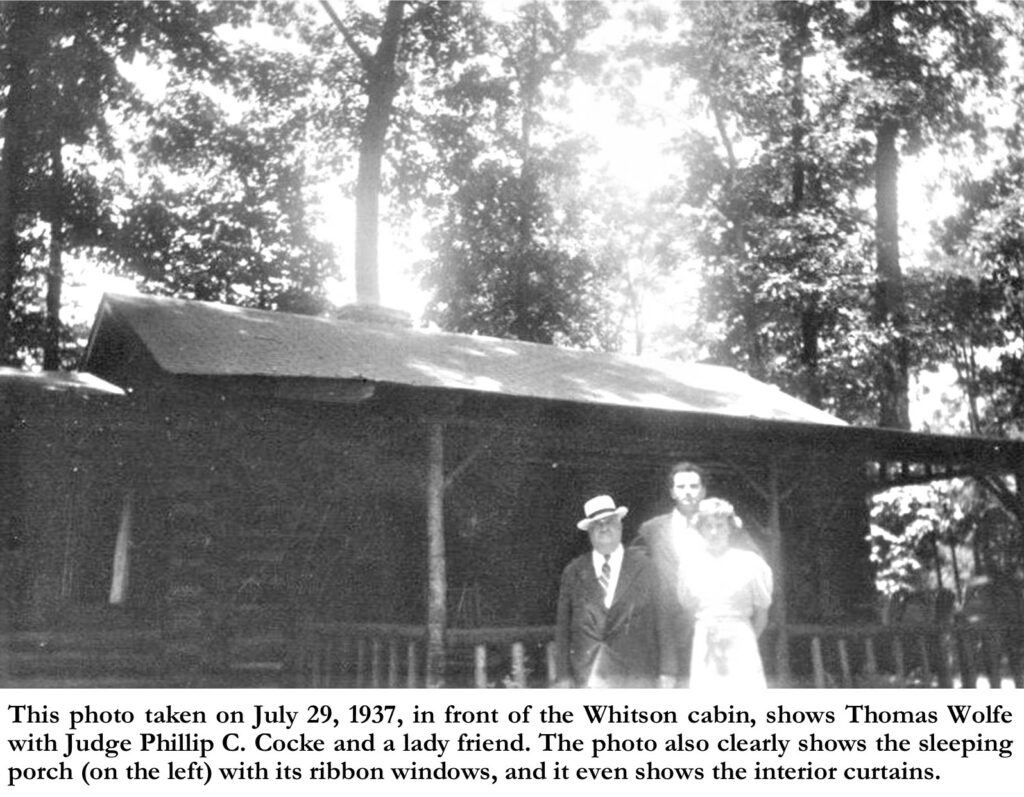

Wolfe arrived in Asheville on July 1, 1937. He called Max from the Biltmore Station and told him that he had arrived and that he would get a taxi out to the cabin and meet him there. As Wolfe did not drive or cook, Max Whitson became his chauffeur for the summer, and a handyman named Ed, was hired to cook and keep house. Four days after he arrived Wolfe hired the first of a series of stenographers, as he intended to keep working throughout the summer. [46] But word soon got out that he was back in town. In fact, just two days after his arrival, on July 4th, his presence was revealed in the Asheville Citizen-Times. “Tom Wolfe To Spend The Summer Writing At A Cabin Near Here”, was the title of the article that all but named the exact location of the “mountain cabin a short distance east of Asheville”.[47] Then on July 10th, little over a week after Wolfe had arrived, an Asheville Citizen-Times photographer “paid a visit”. The following day, a photograph of Wolfe writing at a table in the cabin appeared in the newspaper titled, “Wolfe At Work In Mountain Cabin”.[48] Of course, Wolfe must have welcomed the notoriety as he allowed the article to be written and photos to be taken and published. For an architectural historian like me, these photographs are a treasure trove of information. It is from these photographs that we have evidence of the original construction and layout of the cabin, which will be important if the cabin were to be restored. Sometime after 1937, the interior of the cabin was sheathed in knotty-pine paneling and the sleeping porch was enclosed and poorly constructed additions had been added. For instance, we see in the 1937 photo of Wolfe writing at the cabin table, that there was a window on the west side of the living room, where is now the entrance to a bedroom that was created by enclosing the sleeping porch. At first this made be think that the sleeping had been added since Wolfe’s stay. However, literary references, such as Whitson’s 1971 article, told of Wolfe spending time on the sleeping porch while he was there. I’ve recently found photographic evidence that the sleeping porch was indeed part of the cabin during Wolfe’s stay. One of the many visitors that came to call was Judge Phillip C. Cocke, who came calling on July 29th, along with a lady friend. Wolfe had used some of Judge Cocke’s traits for the character of “Judge Rumford Bland” in Look Homeward Angel. After his visit, the Judge requested some photos of himself and his lady friend with Wolfe, be taken outside the cabin. One of those photos clearly shows the sleeping porch with its ribbon windows, and it even shows the interior curtains.

Despite the many intrusions and unexpected visitors who would just show up at the cabin door, Wolfe did manage get some substantial work accomplished, including the final draft of “A Party At Jack’s”, which would be posthumously published in Scribner’s Magazine, in 1939. However, Wolfe’s stay at the cabin was short lived. During his May visit, Wolfe had first stopped in Yancey County to visit with his mother’s relatives, including his great-uncle, John Baird Westall, a 95 year-old Civil War veteran, whose stories Wolfe would use in a subsequent story called, “Chickamauga”. On May 1, just as he was coming out of a soda shop on Main Street in Burnsville, NC, Thomas Wolfe witnessed a shooting. Although no one was killed in the incident, a few days later another shooting incident involving the same men resulted in a death. While staying at the cabin, Wolfe was served with a subpoena to appear as the state’s witness of the earlier incident. Wolfe attended the trial from August 16 through the 18th. According to Max Whitson, Wolfe never returned to the cabin to live after the trial, instead “he took a room at the Battery Park [Hotel] in Asheville”.[49] Although Wolfe did return to the cabin one more time before he left, for a grand party, overall his stay at the Whitson cabin lasted only about six weeks. But because of Wolfe’s untimely death the following year, 1938, the cabin took on an immortality as representing Wolfe’s final visit home to his beloved “Altamont”.

Years later, as interest in Wolfe was waning, and Max Whitson was approaching retirement, Whitson sold the cabin in 1956 to Joe and June Hodges.[50] In 1960, the Hodges sold the cabin to John W. Moyer,[51] who had also purchased the adjacent Whitson Homestead from Sallie and Jennie Whitson.[52] Around 1972, the Moyer’s divorced and shortly thereafter sold the Whitson house. However, Moyer retained the Wolfe cabin and its 9 ace property. Around 1977, Moyer and his second wife Vallie built a new D-log cabin adjacent to the Wolfe Cabin as their primary residence. In 1983, the City of Asheville passed an ordinance designating “The Thomas Wolfe Cabin” at 1200 Oteen Church Road as “Historic Property”, placing it under the purview of the city/county’s 1979 established “Historic Resources Commission”. In 1999, Moyer decided to sell the property, with both cabins, and offered it first to the city. After numerous revisions of options to purchase, the sale of the Thomas Wolfe Cabin to the City of Asheville was completed on May 3, 2001.[53]

Unfortunately, the city had little interest or manpower to maintain “The Thomas Wolfe Cabin” after it’s purchase in 2001. Discovering the lack of maintenance and advanced deterioration of the cabin, in 2012, the Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County stepped in for an intervention. In May of 2012- the PSABC signed an agreement with the City of Asheville to undertake an extensive study of the Thomas Wolfe Cabin, which included: a Building Assessment outlining the prioritized needs for the property and a Feasibility Study to identify sympathetic future uses of the site. On May 31, 2012- Members of the PSABC met onsite to tour the property, to perform an initial assessment of the site conditions and to discuss the projected goals of the project. At that gathering PSABC displayed their support for the National Trust Campaign “This Place Matters”, through a group photo holding the “This Place Matters” banner in front of the Wolfe cabin. In 2013-2014- PSABC solicited and received a donation of EPDM roofing to install over the Thomas Wolfe cabin roof temporarily to stabilize the structure, until restoration begins, and in addition PSABC prepared selective demolition drawings, and helped the City to expedite a “Selective Demolition” application to the Historic Resources Commission, to remove later “non-contributing” additions on the cabin. These additions were in greater decay than much of the original cabin materials. In 2016, the City, in conjunction with PSABC project manager Craig Cline, followed through and performed the “Selective Demolition” as well as taking other simple stabilization measures, such as improving the air flow around and under the foundation and installing fans and a dehumidifier to slow organic decomposition of the wood structure.

In July of 2018, the City of Asheville issued a Request for Qualifications (RFQ) for Master Planning and Professional Design Services for the Thomas Wolfe Cabin at Azalea Park. A planning team led by preservation on architects Lord Aeck Sargent was selected, and work was authorized to begin in January, 2019. The goal of the project was to update and further develop the work previously completed by the City of Asheville and the Preservation on Society of Asheville & Buncombe County by providing a “comprehensive, multi- disciplinary master plan” for the Thomas Wolfe Cabin and its nearly 43-acre site. A Master Plan and Report were prepared and presented to the City in the Spring of 2020. The proposal presented by Lord Aeck Sargent was for a $9 million-dollar, three-phased, combination tourists and writer’s retreat. The plan called for restoration of the Cabin and rebuilding of the 1930’s treehouse, as well as the addition of new lodging cabins, a large-group lodge structure, and landscape enhancements with improved vehicular pathways and well as new trails and pedestrian paths. Since 2020, social events and a change of leadership at the city has resulted in a de-prioritizing of The Thomas Wolfe Cabin project. The Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County has recently re-activated their advocacy for the preservation of the cabin and have formed a committee to take another look at the project and see if there are alternative ways of re-activating the preservation and use plans for the cabin.

Although the Thomas Wolfe Cabin is historically significant for its 1937 associations with famed hometown author Thomas Wolfe, I propose that it is also historically significant as a remaining specimen of the Log Cabin Revival which swept through the US during the first three decades of the twentieth century. Like many of his fellow-Americans during that period, Max Whitson, built his own rustic log cabin get-away where he could retreat to his own piece of “wilderness”.

Photo & Image Credits: (Note: All cropping and captions by author)

Whitson Cabin-c. 1930- Image # W263-5, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

“Lower Swedish Cabin” photo- Darby Creek Valley Association website: https://www.dcva.org/page-18187

“Harrison & Reform” Poster- “Harrison! and reform!! To the Log cabin boys” Alton, 1840.- Library of Congress website-https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.01601000/

Swiss Chalet Sketch–A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, adapted to North America, by Andrew Jackson Downing. (Wiley and Putnam, London, 1844), page 363.

Old Faithful Inn- Wikimedia Commons contributors, ‘File:-164 – Old Faithful Inn (16431838556).jpg’, Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, 5 January 2022, 20:06 UTC, [accessed 6 May 2022]

Susan Chester Lyman Log Cabin Settlement House- Image # E843-DS, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Wicks Log Cabin Illustration- “Cabin At Hollow Lake- Canada”- Wicks, William S., Log Cabins and Cottages: How to Build and Furnish Them. United States: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1908.

Log Bungalow from The Craftsman– Stickley, Gustav. More Craftsman Homes: floor plans and illustrations for 78 mission style dwellings. United Kingdom: Dover Publications, 1982., page 162.

Old Faithful Inn- Hand-colored tinted photograph postcard of Old Faithful Inn, Yellowstone Park, ca. 1920. Number 13085. Haynes, St. Paul official photographer of Yellowstone National Park. Utah State University. Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections and Archives, Postcard Collection, P0031, Box 1 WY 015- https://digital.lib.usu.edu/digital/collection/highway89/id/1786/

Touring Car-1915 Model T five-passenger touring car outfitted with a lean-to tent.-from “The Evolution of Auto Touring in America”

August 28, 2012, https://www.thehenryford.org/explore/blog/the-evolution-of-auto-touring-in-america/

Foster’s Log Cabin Court– Image # AD166, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

The Pines Log Cabin Bungalow– Image # AD168, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

The Pines Log Cabin Camp– Courtesy of the Staff at “The Pines Cottages”, 346 Weaverville Road, Asheville, NC 28804

Asheville Mineral Springs at Croquet Court–Asheville Citizen-Times, August 9, 1939, page 16.- newspapers.com

Homeland Park Postcard- Image # AC758, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Old Patton Mill/Waterworks- Asheville Citizen-Times, February 21, 1932, page 6.- newspapers.com

Max Whitson Advertisement- Asheville Citizen-Times, October 18, 1928, page 10.- newspapers.com

Colored Photo of Whitson Cabin- Image # W264-4, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Thomas Wolfe at Writing Table in Whitson Cabin, 1937- Image # W266-8, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

Thomas Wolfe outside Cabin with Judge Cocke & Lady Friend- Thomas Wolfe additional papers, Call no. MS Am 2815 , Box 7: items 157-213, Folder 168, Hollis number 990133237160203941 , Harvard University.

“This Place Matters” at Whitson Cabin, 2012- Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County, 324 Charlotte Street, Asheville, NC 28801.

“Stabilized Temporarily-Thomas Wolfe Cabin” Photo- Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County, 324 Charlotte Street, Asheville, NC 28801

[1] “Log Cabin History: The Secrets of Making a Home”, by Judith Flanders. The History Reader, website, by St. Martin’s Press-Posted on September 9, 2015, https://www.thehistoryreader.com/world-history/the-making-of-home-secrets-of-log-cabin-history/

[2] “Log In”, Darby Creek Valley Association website: https://www.dcva.org/page-18187

[3] “What Is the History Behind Log Cabins?”, https://www.zookcabins.com/blog/log-cabin-history/

[4] Ibid.

[5] Asheville and Buncombe County, By Forster Alexander Sondley , (Asheville, NC: The Citizen Company, 1922), page 79.

[6] “What Is the History Behind Log Cabins?”, https://www.zookcabins.com/blog/log-cabin-history/

[7] “Romanticism’s Influence on Architecture”, Stevenson Library Digital Collections,

[8] The Architecture of Country Houses, by Andrew Jackson Downing. (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1859), page 40.

[9] Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “picturesque”. Encyclopedia Britannica, Invalid Date, https://www.britannica.com/art/picturesque -Accessed 20 April 2022.

[10] https://www.theadkx.org/exhibitions-events/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/natures-art/great-camps/

[11] The Architecture of Country Houses, by Andrew Jackson Downing. (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1859), Preface, page v.

[12] The Log Cabin: An American Icon, by Alison K. Hoagland. (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2018), page 175.

[13] “A Brief history of the American Arts & Crafts Movement, 1887-1930”, by Thomas Magoulis and Dawn Krause. -Two Red Roses Foundation, Palm Harbor, FL. http://www.tworedroses.com/newsletters/A%20Brief%20History%20of%20the%20American%20Arts%20and%20Crafts%20Movement.pdf?pdf=Brief-AC-History

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Farms: The Quest for an Arts and Crafts Utopia, by Mark Alan Hewitt (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2001), page 216.

[17] “Quick History of the National Park Service”, National Park Service website: https://www.nps.gov/articles/quick-nps-history.htm

[18] “Parkitecture, The NPS Rustic Style”, National Park Service website: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/architecture/parkitecture.htm

[19] The Log Cabin: An American Icon, by Alison K. Hoagland. (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2018), page 148.

[20] “Power Plant Is Almost Ready”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 29, 1924, page 9.-newspapers.com

[21] “Tourist Camp discontinued”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 11, 1926, page 40.-newspapers.com

[22] Ibid, page 190.

[23] Ibid, page 191.

[24] “W. N. C. Tourist Camps Draw Large Patronage From Restless Motorists”, Asheville Citizen Times, July 31, 1932, page 7. -newspapers.com

[25] “Cabin Camps on Highway 25”, Asheville Citizen-Times, June 17, 1940, page 59. -newspapers.com

[26] 04/22/1920- William C. & Myrtle Gass to Zebulon & Andrey Foster, LOT 31 1/2 PART 32 BK 198 P 162, Db. 241/21.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[27] Info from: “Foster’s Log Cabin Court”, Woodfin, Buncombe County, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, BN1406, Listed 5/1/2017, Nomination by Clay Griffith. http://files.nc.gov/ncdcr/nr/BN1406.pdf

[28] 03/18/1922- Marian A. Putnam to W. W. & Ida Pruett, LOT 29 1/2 BK 198 P 162, Db. 256/95.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[29] There is the possibility that the log bungalow was on the lot when the Pruetts purchased the property, however especially with W. W. Pruett’s association with Louis Carr Lumber, it seems most likely that the Pruett’s built the bungalow.

[30] Asheville Citizen-Times, November 22, 1924, page 11.-newspapers.com

[31] H. C. & Annie Mills to W. W. & Ida Pruett WEST MARGIN ASHEVILLE WEAVERVILLE HIGHWAY Db. 306/160.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds

[32] 11/05/1932 HOMELAND PARK, INC- [INC] Db. C013/306.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[33] “Come Out to Homeland Park”, Asheville Citizen-Times, June 11, 1933, page 54.- newspapers.com

[34] 09/12/1795 (rec’d- 10/17/1796) George Ramsey to William Whitson ROSSES CREEK Db. 3/102.-Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[35] 01/04/1814 (rec’d- 06/08/1824) John Patton to Joseph Whitson 180 ACRES SWANNANOA RIVER Db. 13/158. “on both side of the Swannanoa River, including the Big Bend…”.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[36] Others have dated the Whitson house at 1010 Oteen Church Road as having been built in the 1920’s, however, I believe it was built by Dr. Whitson prior to his death in 1906. I believe this to be so, as upon his death, Dr. Whitson willed the house to his wife Jane E. Whitson. In the 1900 census (prior to his death), Dr. Whitson is listed as living in the house with his wife and six adult children. In the 1910 and 1920 censuses, Jane is listed as living in the house with six adult children. Jane died in 1920, apparently intestate. In the 1930 census, the house is occupied by their unmarried daughter, 59 year old, Sallie Whitson (listed as head of household), along with her three unmarried sisters, Mary, Jennie, and Hattie, along with her older brother Henry L. Whitson (75 yrs. old). So I don’t think that it is likely that these unmarried siblings could have, or would have wanted to, replace the family homestead after the death of their parents.

[37] Year: 1930; US Federal Census-: Asheville, Buncombe, North Carolina; Page: 23B; Enumeration District: 0006; FHL microfilm: 2341409-Ancestry.com

[38] 05/27/1930 O. L. Israel, et al, Commissioners to Whitson Heirs (enumerated) REPORT OF COMMRS & DECREE Db. 424/427.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[39] Asheville Citizen-Times, August 14, 1932, page 10.- newspapers.com

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid

[42] “Exchange Club Holds Outing in Evening”, Asheville Citizen-Times, June 20, 1935, page 8.- newspapers.com

[43] “Of Tom Wolfe’s Summer Retreat To Local Cabin”, Asheville Citizen-Times, October 3, 1971, page 43.- newspapers.com

[44] Ibid.

[45] Quote from a letter from Thomas Wolfe to his mother Julia Wolfe, dated June 26, 1937. –Thomas Wolfe: An Illustrated Biography, by Ted Mitchell. (New York, NY: Pegasus Books, 2006) page 235.

[46] “Of Tom Wolfe’s Summer Retreat To Local Cabin”, Asheville Citizen-Times, October 3, 1971, page 43.- newspapers.com

[47] “Tom Wolfe To Spend The Summer Writing At A Cabin Near Here”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 4, 1937, page 4, Section A.- newspapers.com

[48] “Wolfe At Work In Mountain Cabin”, Asheville Citizen-Times, July 11, 1937, page 8, Section D.- newspapers.com

[49] “Of Tom Wolfe’s Summer Retreat To Local Cabin”, Asheville Citizen-Times, October 3, 1971, page 43.- newspapers.com

[50] 04/19/1955 Edward Maxwell Whitson to Joe T & June K Hodges 9.05 ACRES SWANN LAKE Db. 757/269.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[51] 04/25/1960 Joe T & June K Hodges to John W Moyer 9.05 ACRES Db. 828/31.- Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[52] 07/11/1960 Sallie Whitson & Jennie Whitson to John W & Jeanette Moyer SWANNANOA TWP Db. 831/297. – Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[53] 05/03/2001 John W. Moyer to City of Asheville [DEED ] OTEEN CHURCH RD 3 TRACTS PB 80/51 Db. 2478/880. -Buncombe County Register of Deeds.