by Dale Wayne Slusser

“Two hundred feet below under the shade of a pine tree a log cabin snuggles into a laurel thicket,” writes Muriel Sheppard in her 1935 book, Cabins In the Laurel, her literary portrait of life in the coves, hollars, hills, and mountains of Western North Carolina. At first her book was not appreciated by the locals that she portrayed, as she described her own image of Appalachian life, instead of how it really was in the 1930s. She went to great lengths to stage her own vision, such as having the locals dress in their old linsey-woolsey instead of their new store-bought clothes for photographs and asking them to use thrown clay pots and iron kettles rather than their store-bought pots and pans, when being photographed cooking meals. However, later generations of readers began to appreciate Sheppard’s portrayal of life in days gone by. And as John Ehle, famed North Carolina writer, in his forward of the 1991 reprint of the book points out, not only are her portrayals accurate for an earlier time (albeit 1890-1900 rather than the 1930s) but also, for us today, “it offers the most friendly, easily read, vigorous, zestful portrait of Appalachians we have from the past.”[1]

However, I do agree with one specific complaint of Sheppard’s book, that “the pictures selected for use in the book appeared to be out of the past as well, mountain cabins instead of valley houses and barns.”[2] Although there may have been some cabins built “in a laurel thicket”, they were a rarity, built only in the most remote coves. My study of the nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century architecture of Western North Carolina indicates that most rural houses, whether log or frame, as part of a farmstead were built in the lowlands or at least on flat cleared meadows, to be close to the farmer’s fields. The current craze for building cabins on mountaintops “for the view” or in the woods “for privacy” was not the mindset for early Appalachian farmers who needed to live close to their fields and close to roads for getting their produce or livestock to market. Two representative early cabins in Big Sandy Mush, one log and one frame, bear this out.

Sometime shortly after the cessation of the Civil War, former slave Henry Ervin Boyd built a one-room log cabin on property not far from where he was born and raised, along the Big Sandy Mush Creek in northwest Buncombe County. It appears that Ervin Boyd was the son of Dorcus Boyd, a former enslaved servant of the James Boyd family. In the 1870 census, where we find the first and only mention of Dorcus in a census, she is said to be 60 years old, and “keeping house” for Marcus King, next door to her son Ervin Boyd and his wife and their children. Living with Dorcus was her 17-year-old daughter, Lucinda. These relationships are verified by the 1853 will of James Boyd, where Dorcus, Henry and Lucinda are named along with Boyd’s other “negroes”. In fact, a later codicil was added to Boyd’s Will, willing Dorcus (after the death of his wife Rachel) to his son Robert Boyd, instead of to his son John B. Boyd as stated in the earlier Will. Robert Boyd was further instructed by the codicil that he was to “permit the said Dorcus …to live on some part of the Land bequeathed to the said Robert, and to enjoy the benefits of her own labor as a free woman, uninterrupted by, the said Robert, or any other person…”. Henry and Lucinda had been willed to Robert as well.

In 1874, Ervin Boyd purchased fifty acres of land, just southwest of the Boyds’ lands. He purchased the land from the heirs of Robert G. A. Love. Love had settled in Waynesville; the land purchased by Ervin had been part of Love’s “Speculation Lands” he bought as investment property, but had never occupied. It is generally assumed that shortly thereafter, Ervin Boyd built his 1-1/2 story log cabin on his newly purchased property. However, I suspect that he bought the property not long after the Civil War ended but had not been given a proper deed until 1874. The 1870 Census shows that he not only owned his property where he was living, but that the property had a real estate value of $176.

Ervin chose a site on the flat lowland floor of a narrow valley in a mountain cove, along Sandy Mush Creek. He built his cabin perpendicular to and between the road to the south and the creek to the north. Flat arable fields surrounded the house on three sides.

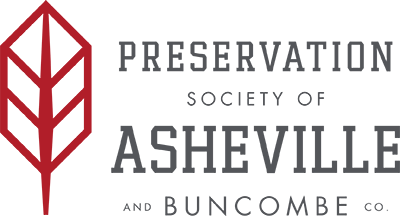

We know that there was a sawmill nearby, yet Ervin chose to build his house of log instead sawn timbers. This was no doubt an economic decision, as he could use felled trees from his own land and hand-cut the logs using just an axe and adze, all for little or no monetary outlay, whereas it would take ready cash to have logs milled into timbers. Using a broad axe and adze, Ervin Boyd turned his felled trees into long straight-sided logs. Although the axe and adze marks have largely weathered away on the exterior, they clearly show on the interior. Instead of using expensive and hard-to-get wrought nails to secure the logs together, Boyd cut half-dove tail notches into the ends of each log to lock them together at each corner. This type of joint was so effective that even 150 years later, despite being weathered and decayed, the logs remain securely locked together at the corners.

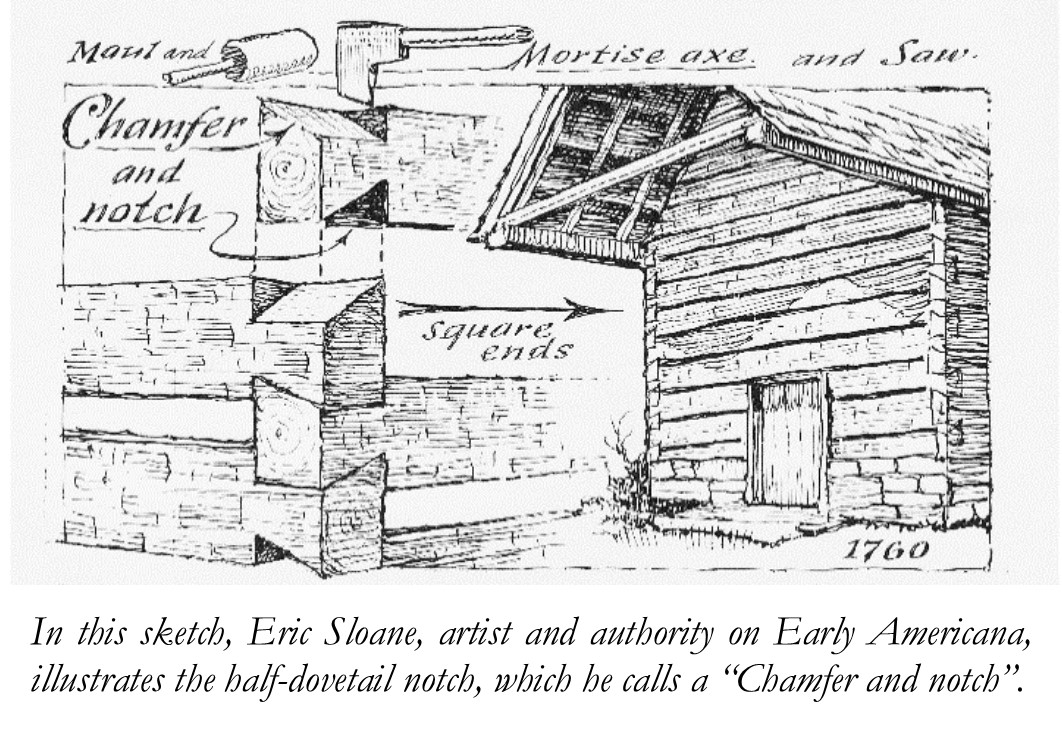

Boyd built his one-room cabin to be 16 feet deep and 18 feet wide, with a sleeping loft. Like Early American houses built in New England, known later as “Cape Cod Style” houses, this story and a half style was very prevalent for early houses in WNC, especially for log houses. However, in the Cape Cod houses, the roof rafters rested just above the second-floor joists, with low “knee walls” which sat inside the front and rear walls about four to five feet as secondary supports. But in the log houses the second story low “knee wall”, built of three or four rows of logs, on which rested the roof rafters, sat flush with the plane of front and rear walls. The loft floor, which essentially functioned as a second story, was constructed with log floor joists mortised into the front and rear walls. The mortises show clearly on the Boyd cabin, as a row of square holes in the logs just above the front and rear doors. Unfortunately, most of the floor joists are gone or in severe decay.

Sometime later, the northern cabin (pen), was erected ten feet from the original cabin, forming a “dog-trot” configuration. A new roof connected the two “pens”, creating an open breezeway between, where dogs, critters, and humans could trot through. Later the breezeway at the Boyd cabin was filled in with framed walls with exterior clapboard siding to create additional interior rooms.

The “dog-trot” configuration was prevalent in log-cabin houses built in Appalachia in the late eighteenth and early late nineteenth centuries. Scholars have debated why this was a prevalent configuration for log-cabins. In my opinion, the best explanation is proposed by historian, Jerah Johnson, who writes that “adding to a log house is a real problem.”[3] As he further explains: “There is no simple and effective way tie a new log wall into an existing log wall, which was a problem commonly faced by frontier settlers.”[4] Johnson also explains that is was just not practical to erect a new log wall adjacent to an existing log wall as the result would be “a wasteful, clumsy, rot-inviting, double-log thick wall in the middle of the now two-room house. Better to place the new pen apart from the old one and simply connect the two by bridging the intervening space with a floor and roofing over it, in effect creating a porch through the middle of the house, which was in fact the way dog-trot passageways were thought of, as porches rather than halls.”[5] Johnson even elaborates that the dog-trot configuration was also practical if a settler set out to build a two room cabin from the start, as this would negate the need for having to find extra-long logs that would be required for the front and rear walls. I would add that most settlers built their cabins by themselves, or at best with little help from others, and therefore shorter log lengths would have been easier to handle.

One interesting feature of the later (northern) cabin was its two-story stone chimney. The second-floor loft fireplace was an added luxury, as sleeping lofts were typically unheated, relying only on radiant heat from the exposed chimney to take off the chill. Though mostly built for function, the Boyd fireplace displays a bit of style, having a trimmed out arched lintel. The interior of this loft seems to have been finished off with flush horizontal boards.

Oral tradition and/or early architectural surveys say that Ervin’s son Thad Boyd built the northern pen, presumably after he inherited the property. However, I suspect that Ervin actually built the northern pen shortly after he built his original cabin, as not only did Thad not inherit the property until 1904, but by then Thad had married, purchased and was occupying his own farm of 40 acres just down the road from his parents.[6] Also, Ervin certainly had a need for a larger house, as even by 1870 the census showed that he was living in the house with his wife, Emeline, and ten children, aged 6-15. A later census showed that Ervin and Emeline ended up having twelve surviving children, all of them living one house. By 1900, only Ervin and Emeline and their 35-year-old daughter, Mary Cordelia, remained in the house. After Ervin’s death in 1903, Emeline went to live with Thad and his family on Thad’s farm. I suspect that Mary, who never married, occupied the house until her death in 1923 at the age of 59.

In 1937, Thad sold his farm and moved back to his boyhood home, where he lived until his death at the age 77 in 1939. Thad willed the property to his son Buck, who in 1946 sold the property to his brother Wickes Boyd. Wickes Boyd owned the property until 1971, when he finally sold it out of the family to Earl & Frances Berger, grandparents of the current owners. The house has been used as a barn for over 40 years and is in an advanced state of decay.

In comparison and contrast to the Boyd cabin is the Ray Hearne cabin at 91 Bald Creek Road. Like the original Boyd cabin, the Hearne cabin was originally built as a one-story structure with a sleeping loft, accessed by a ladder. In contrast to the Boyd cabin, the Hearne cabin was built of frame construction, with vertical board and batten exterior sheathing. The Hearne cabin is divided into two rooms in the main section and has a small kitchen in a rear wing to the north. The cabin’s origins are a bit unclear, as it appears to have been originally built as a tenant house for the “old James Lowry farm”, and not as a family homestead. I suspect that it was built after the farm had been sold out of the Lowry family into the hands of Wiley J. Worley in the 1870s, or later by the Waldrops in the 1890s.

Any discussion of both cabins contains little mention or determination of style, as both were built out of necessity for shelter, combined with available materials, local technology, and skill of the builder. Although later additions of bigger windows or clapboards over logs seemed to bring a sense of style to these cabins, even the additions were no doubt motivated more by function than style-bigger windows for more light or clapboards to stop the draft and to keep the logs from further decay.

Like many small cabins built in rural Western North Carolina, outdoor spaces, especially covered areas like porches, were utilized as extra spaces for working and living. The Hearne cabin has a wide wrap-around porch on its south and east sides. The porch provides shade from the summer sun and a place to catch the breeze for cooling off. A small porch is tucked behind the main cabin, to the side of the rear kitchen, at the back door.

A natural spring is behind the Hearne cabin. A graceful stone wall surrounds and protects the spring; from the deep spring, overflow is moved into the spring house where cement channels provide cold water for keeping dairy and other products chilled. A natural spring was often a preferable site for 19th-century cabins or farmhouses, as this negated having to dig a well for fresh water. Also, a spring-house could be erected over the spring to provide cold storage before the days of ice boxes and refrigerators.

Remnants of a stone foundation, crumbling just above the spring, suggest either an earlier cabin or a former barn or other type of agricultural building. Late 19th-century and early 20th-century maps show a gravel road coming up the hill/meadow from the paved Sandy Mush Road (now called Bald Creek Road), indicating that this was a known homesite since that time.

Rustic wood boards cover the interior walls of the Hearne cabin. The interior walls of most farmhouses in 19th-century WNC were covered with boards (whether flush or beaded) instead of plaster. This was not a matter of style, like the modern HGTV inspired craze for “ship-lap”, rather this was a function of availability of materials and the skill of the builder. Sawn lumber from local sawmills, both private and commercial, were readily available, whereas skilled plasterers were not only hard to find, but expensive to hire.

The Hearne cabin has a brick and stone fireplace in its living room. The fireplace mantle appears to be 19th-century, with elegant beaded Egyptian influenced tapered boards likely built using either recycled woodwork components, or handmade parts. The wall surrounding the mantle had narrow beaded boards and was later covered with insulation board and drywall.

A small sleeping loft in the Hearne cabin is accessed by a steep ladder in the living room. This arrangement was very popular in small 19th-century cabins, as it provided use of the space under the roof without the necessity of a staircase which would have taken up valuable floor space. As the house lacked sufficient windows for Ray’s desire of light and ventilation, a large window (rescued from the Vanderbilt Hotel) was added to the gable end of her loft. This was a luxury not often afforded in 19th-century cabins.

The Hearne and Boyd cabins show us that historic preservation is not just for the architecturally or historically significant old building, but for any old building that one cherishes. Not only does restoration and preservation of these small cabins give us a glimpse into the lives of our ancestors, but they also make sense ecologically for us today, for as the modern bumper sticker so aptly states: “Historic Preservation: The Ultimate Recycling”.[7]

Photo Credits:

- Boyd Cabin photos- by Andrew Wing. Used with permission. See more stunning architectural photos by Andrew at https://andrewwingphoto.pixieset.com/

- Ervin Boyd Cabin aerial– Google Earth Image-labels added by author.

- Sloane’s Notch Illustration– from A Museum of Early American Tools, by Eric Sloane. (New York, NY: Funk and Wagnalls, 1964).

- Hearne Cabin photos– by Jessie Landl, Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

- Sloane’s Sleeping Loft Illustration– from Diary of An Early American Boy: Noah Blake 1805, by Eric Sloane. (New York, NY: Wilfred Funk, 1962).

[1] Cabins In the Laurel, by Muriel Earley Sheppard; photographs by Bayard Wooten. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1935, 1991.) page xi.

[2] Ibid, page x.

[3] “The Vernacular Architecture of the South: Log Buildings, Dog-Trot Houses, and English Barns”. Essay by Jerah Johnson in Plain Folk of the South Revisited, edited by Samuel C. Hyde, Jr. (Louisiana University Press, 1997), page.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Thad’s farm was a portion of the old James Lowry farm, that Thad had purchased from Lowry heirs in 1897. See deed in Deed Book 280, page 66, in the Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[7] Phrase originally popularized by Preservation North Carolina-https://www.presnc.org/greener-side-preservation/