By Dale Wayne Slusser

Perched high on a steep wooded site on Sunset Mountain, accessed from below, up a series of rustic stone steps and a magical pathway that winds up the hill through the dense ivy ground-cover, is an enchanting Storybook-style cottage, appropriately named, “Faraway”. Built in 1926 as a summer home for Louis Huntington Moore, a businessman from Montgomery, Alabama, this unique home is attributed as the creation of New York architect, Julius Gregory, who was famed for his English and Medieval Revival designs.

Louis H. Moore and his wife Sarah had been visiting Asheville for their summer getaways for several years before building their first summer home in Kenilworth Park in 1923.[1] The Moores built a two-story frame Colonial Revival at the end of what was then Chiles Avenue (now Westchester Drive), overlooking the Swannanoa River. However, in 1925, the Moores decided to sell their Kenilworth home and build another summer home in Grove Park in northeast Asheville. It’s not clear why the Moores decided to build again, but I suspect that Kenilworth Park was a bit too remote from downtown Asheville and the high-society social life that the Moores desired. For their new home, the Moores purchased a lot on Fairmont Road, in Grove Park[2] in the summer of 1925. Their new lot provided the same elevated view and seclusion of their Kenilworth lot, but was closer, not only to downtown Asheville, but also to the Grove Park Inn, which was frequented by the rich and famous from across America.

The Moore’s new steeply sloped lot was on Fairmont Road, in the eastern section of the Grove Park development. The lot was accessed from Fairmont Road on the lower west side of the lot, although Fairmont Road, a winding road that switch-backs up Sunset Mountain, also formed the western boundary of the lot at the top of the slope. This unique lot, which resembled those in “Hollywoodland”, California’s 1920’s Hollywood hills development, required an appropriately unique house. The deed covenants required that any house built on the lot was to cost “not less than $10,000” and that the house must front on Fairmont Road, “facing west”. The Moores, or their designer, decided to place the new house at the top of the slope, no doubt to maximize its wonderful views towards the western Mountains.

“Mr. & Mrs. Louis H. Moore, their daughters, Misses Sara and Margaret will leave Sunday for Asheville, N.C.,” announced the July 7, 1926 edition of The Montgomery Advertiser, “where they will be at the Piping Hot, until the completion of their summer home.”[3] The “Piping Hot” was a tearoom/inn at 286 Charlotte Street.[4] We can assume from this article that the Moore’s new home was nearly complete by the summer of 1926, and that they expected to move into it by the end of their summer visit. They had sold their Kenilworth house in March of 1926[5], probably in anticipation that their new home would be completed by the time they returned in the summer.

The Moore’s new home, which they called “Faraway” (as they had called their Kenilworth home) was designed in an English Medieval Revival Storybook Style. According to Arrol Gellner and Douglas Keister, in their book, Storybook Style: America’s Whimsical Homes of the Twenties[6], the Storybook Style, which was a short-lived style during the 1920s and early 1930s, began in California along with the development and rise of the film industry. Art directors and stage-set designers carried their skill in designing the artifice into the design of their own homes. By the mid-1920’s, even classically trained architects, were designing in the “Storybook Style”. However, most of their designs were exaggerations of the then prevalent revival styles being proliferated by architects and builders who had seen and experienced the rural architecture of England and Europe while serving in World War I. These storybook homes, instead of resembling the dwellings of witches or fairies, as the earlier California/Hollywood storybook homes had done, were being designed to resemble the idyll of rural English and European farmhouses, cottages or castles. Although “Faraway” does evoke the idyll of a rural English Cottage, it also evokes a storybook cottage from a fairytale. It’s wooded setting, with it’s small mountain brook running through the property, reminds me of a friendly woodland cottage, where weary travelers could be assured of finding food, lodging, and rest before continuing on their journey to the sorcerer’s castle to rescue the imprisoned princess!

Although I have not yet found any conclusive documentary evidence (such as architectural drawings or news reports) to support my suspicion, I strongly suspect that the architect of the Moore’s new home on Fairmont Road was Julius Gregory, a New York architect noted for his English Medieval-Revival homes. A comparative analysis of the home’s architectural design and details with known Julius Gregory designed houses, shows us that even if “Faraway” was not designed specifically by Julius Gregory (although I think that it was), it was designed in Julius Gregory’s style, perhaps as a knock-off. And in a least case scenario, we can certainly say that its design was inspired/influenced by Gregory’s designs.

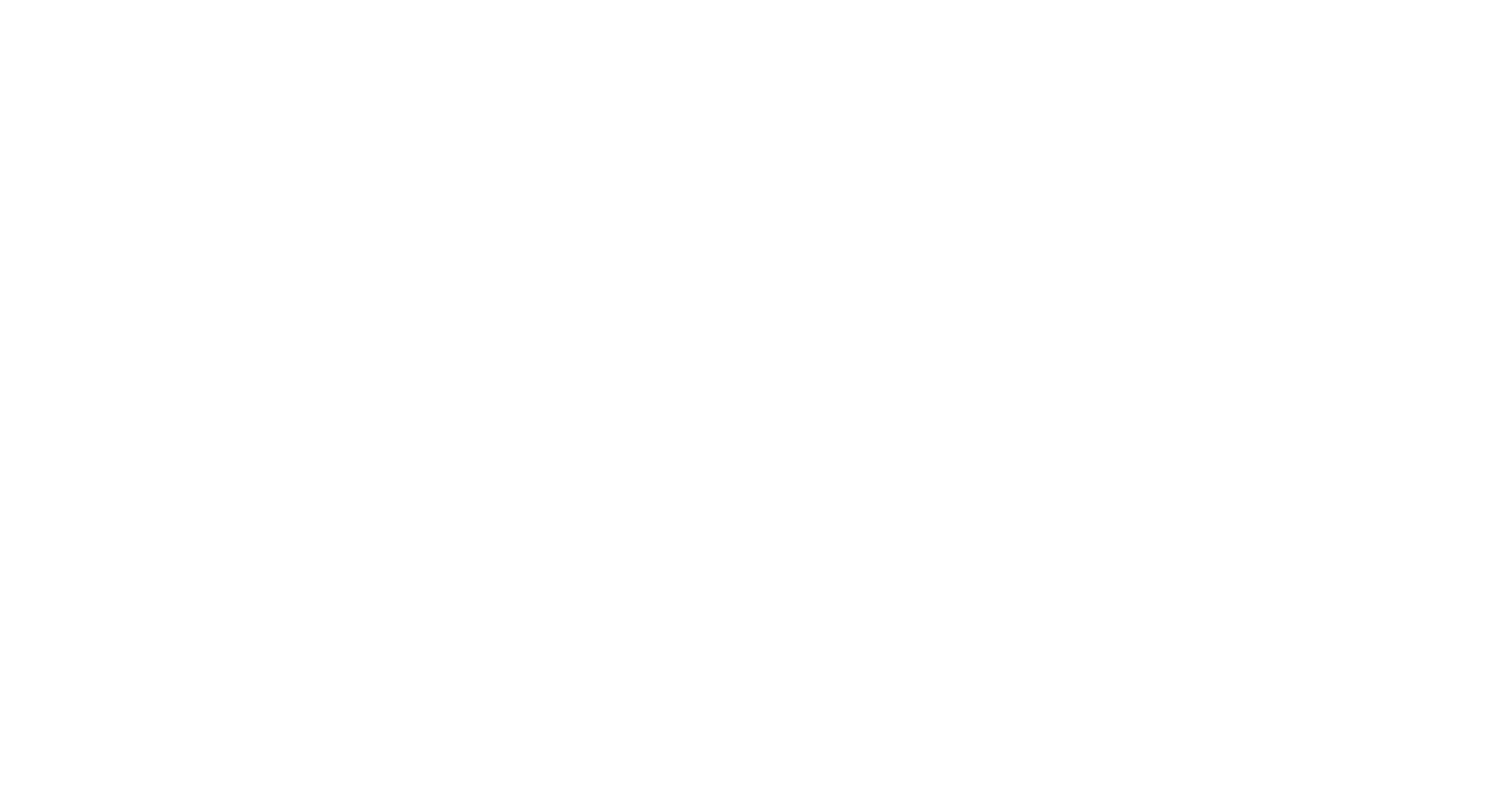

Julius Eugene Gregory was born in 1875 in Sacramento, CA to Eugene Julius Gregory and his wife Emma. Julius graduated from the University of California at Berkley in 1897 with a degree in Mechanical Engineering. But prior to his graduation, in 1894-95, Julius, along with his father, had invented a photo machine to be used by the railway company to insert an identification photo onto each ticket. Following graduation from Berkley, Julius moved to New York City where he began his first career as an inventor, perfecting his new machine and pursuing appropriate patents, as well as acting as a patent- agent on other inventions. In 1906, the final revised patent and improvements to the photographic machine were completed, so Julius along with Thomas Wiseman, and chemist Julian Florian, incorporated the “Photo Machinery Company” and began manufacturing his photographic machine. But sometime around 1912, Gregory made a dramatic career change, when the engineer/inventor/manufacturer became Julius Gregory, Architect. By 1920, Gregory’s homes (designed mostly in the Medieval-Revival style) were being widely publicized in the architectural journals and house magazines of the day, and even two houses were featured in a 1920 book of House & Garden homes.[7]

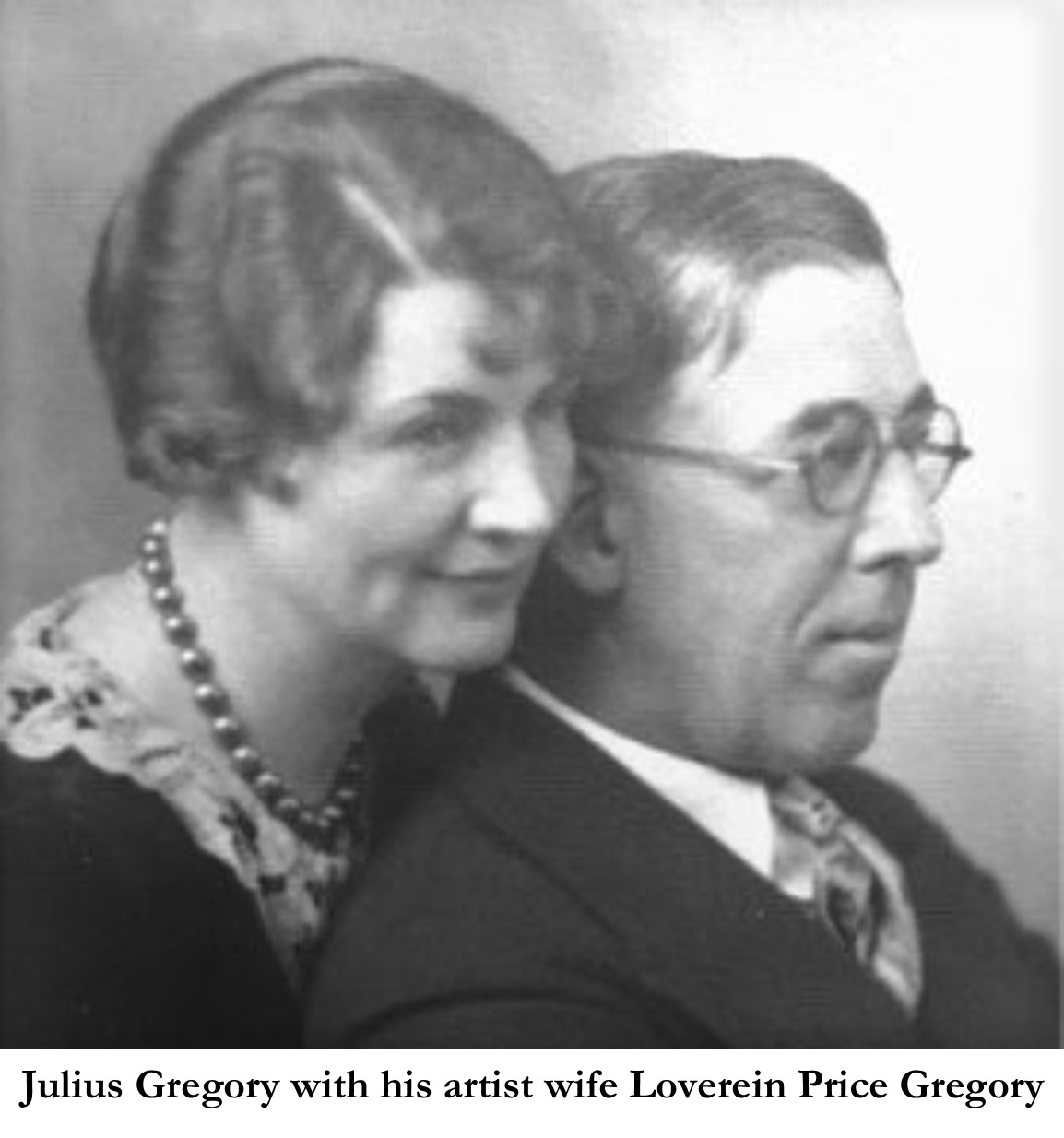

In 1924, just one year before the Moore’s were to build their new home, builder/developer, Allison C. Clough built two English Medieval-Revival houses on Kimberly Avenue in the western section of the Grove Park development. Clough had commissioned Julius Gregory to design the two houses. A comparison of the Moores’ new home, “Faraway” to the Clough houses[8] shows a number of similar characteristics and details. In fact, the current owner of one of the Clough houses was the one who alerted me to “Faraway” and its striking similarities to his house.

“Faraway”, like the Clough houses was designed to look like an old English cottage. In his article, “On the Charm and Character of the English Cottage” published in the March 1926 edition of the Architectural Forum,[9] Julius Gregory gives us not only a description of the “old English cottage”, but also a description of his modus operandi for the design of “Faraway”:

“Texture, the elusive quality of a surface which makes it pleasing to the eye, permeates our picture of the old work. And it pleases because it is the product of the understanding hand of the craftsman, done in humble reverence and with a feeling for his material. There is no striving for effect, nothing more than a straight-forward use of wood, brick, stone, and mortar in simple and direct way, resulting in a surface that is hand-made, beautiful to look at, and one that will be satisfying through all time.[10]

“Another feature of these old English cottages, and hardly less important than that of texture, is simplicity of mass; large restful areas of wall and roof with spare spotting of openings; the windows grouped together and not many in number; the simple doorways, usually framed in oak and with solid aged doors.”[11]

This “simplicity of mass” and “large restful areas of wall and roof with spare spotting of openings” is what sets apart Gregory’s cottages from similar styled “English-cottages”. Next, let us look at the striking similarities of “Faraway” both to the Clough cottages (at 5 & 7 Kimberly Avenue) in Asheville, which we know for certain were designed by Julius Gregory, as well as other known Julius Gregory designed houses in the northeast.

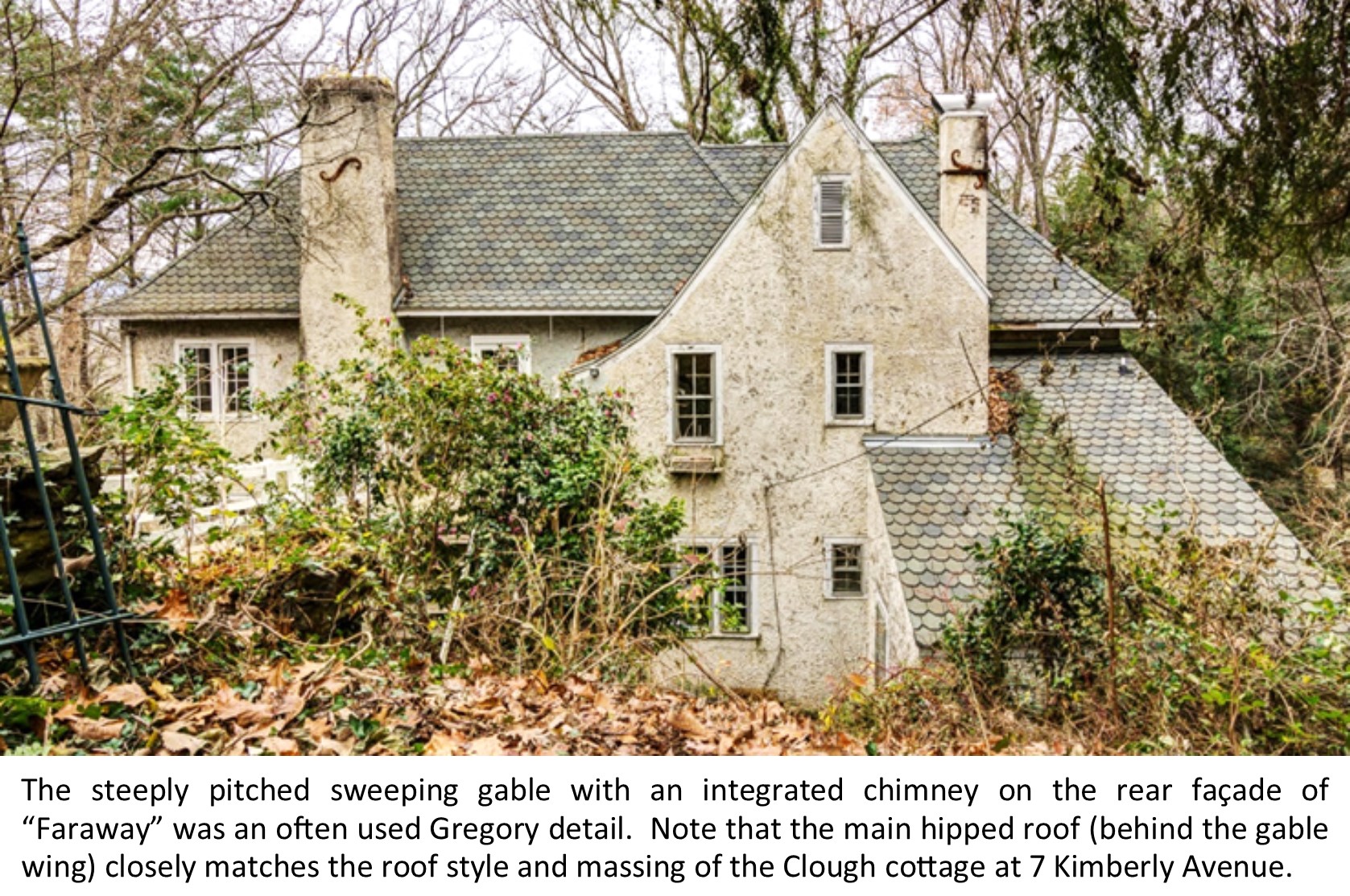

The steeply pitched hipped roof on “Faraway”, with it’s flared eaves (aka coyau or sprockets), and its adjacent secondary hipped roof which bears lower on the house walls, (including a single slightly raised second-floor dormer) closely matches the roof on 7 Kimberly Avenue. I suspect that the adjacent lowered secondary roof was an artifice used on the houses to give the appearance of history, as if the original “old English cottage” had acquired a later addition (or as the English would say, a later “extension”). This design devise of giving a new house an old history, it’s own fictitious story, was often used by Classical and Traditional Revival architects of the early twentieth-century. Classical and Traditional Revival architects of the twenty-first century still use this same devise. In his book, “Creating A New Old House”, architect Russell Versaci has categorized this devise as “Pillar Three” in his “Pillars of Traditional Design”:

Part of the charm of an old house is that it tells a tale of changes over time. In a new house it is possible to script a story of growth over many years- a room the was remodeled, a wing that was added, or a screen porch that was glassed in-portraying the house as an accumulation of additions. [SIC] A new house acquires the soul of the past when it tells a story that covers its newly minted form in a mantle of make believe.[12]

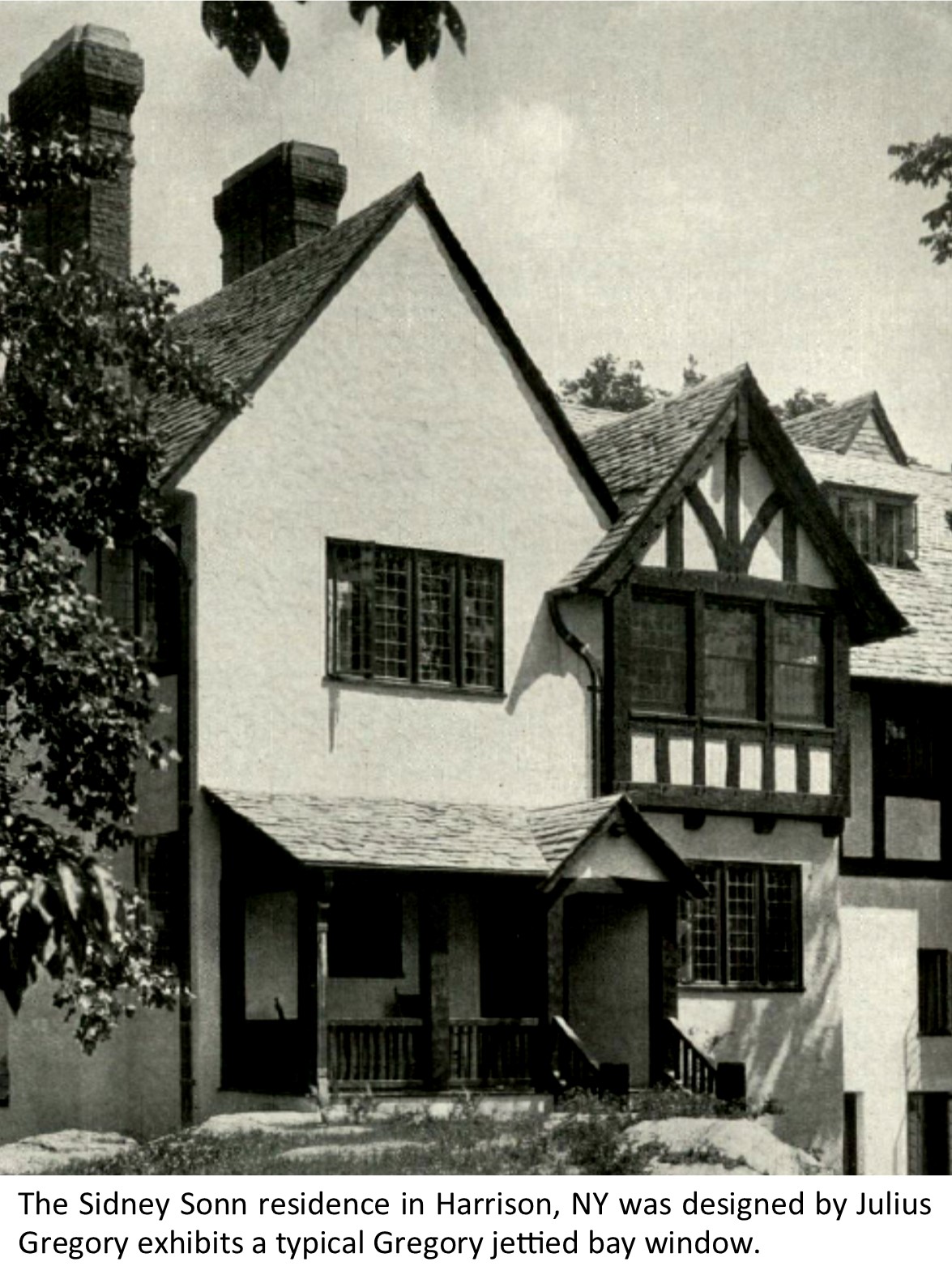

Perhaps the most striking similarity shared by “Faraway” with both the Clough cottages and other known Gregory-designed “old English” houses is the use of a single projected (or jettied) timber-frame bay on each of the houses. Although faux timber-framing was and is a typical artifice used on Tudor Revival houses, Gregory’s sparing use of a single projected (or jettied) timber-frame bay, is unique to his designs. “Jetties” (projected timber-frame bays) were used on many medieval and Tudor houses, to create space on the upper floors, by projecting the floor joists beyond the building line below. The jettied bays on the Clough cottages are on the rear of those cottages, but on “Faraway”, the jettied bay is prominent on the front façade, above the front door.

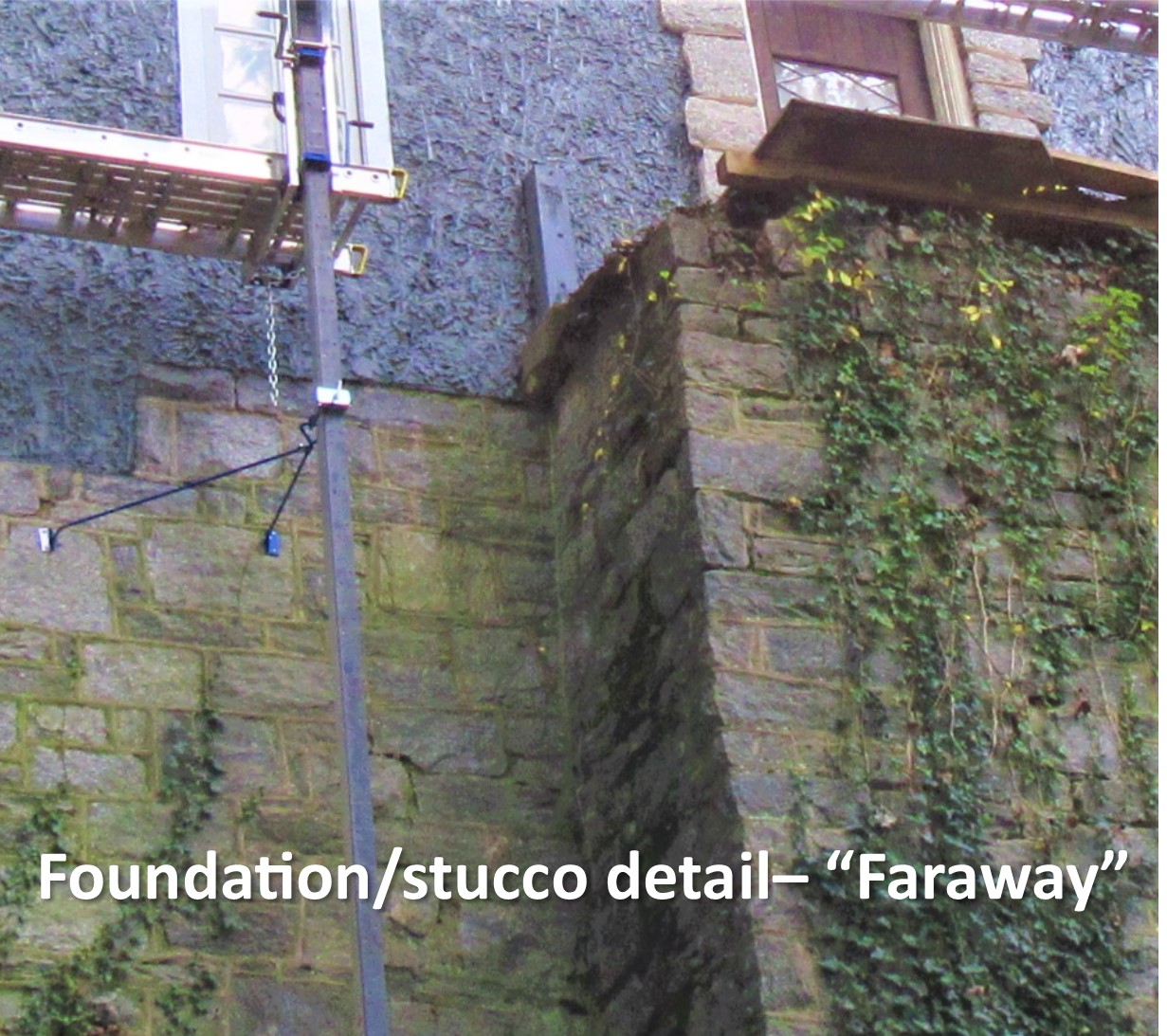

Another feature that “Faraway” shares with the Clough cottages is the use of stone on the foundation, and the detail of blending bits of the foundation stone up into the stucco of the first-story walls. This is another artifice used on Medieval- Revival and Storybook-style architects to simulate age and attrition, as if an earlier house was torn down to the foundation and rebuilt during a later renovation. Julius Gregory frequently used this detail on his Medieval-Revival houses.

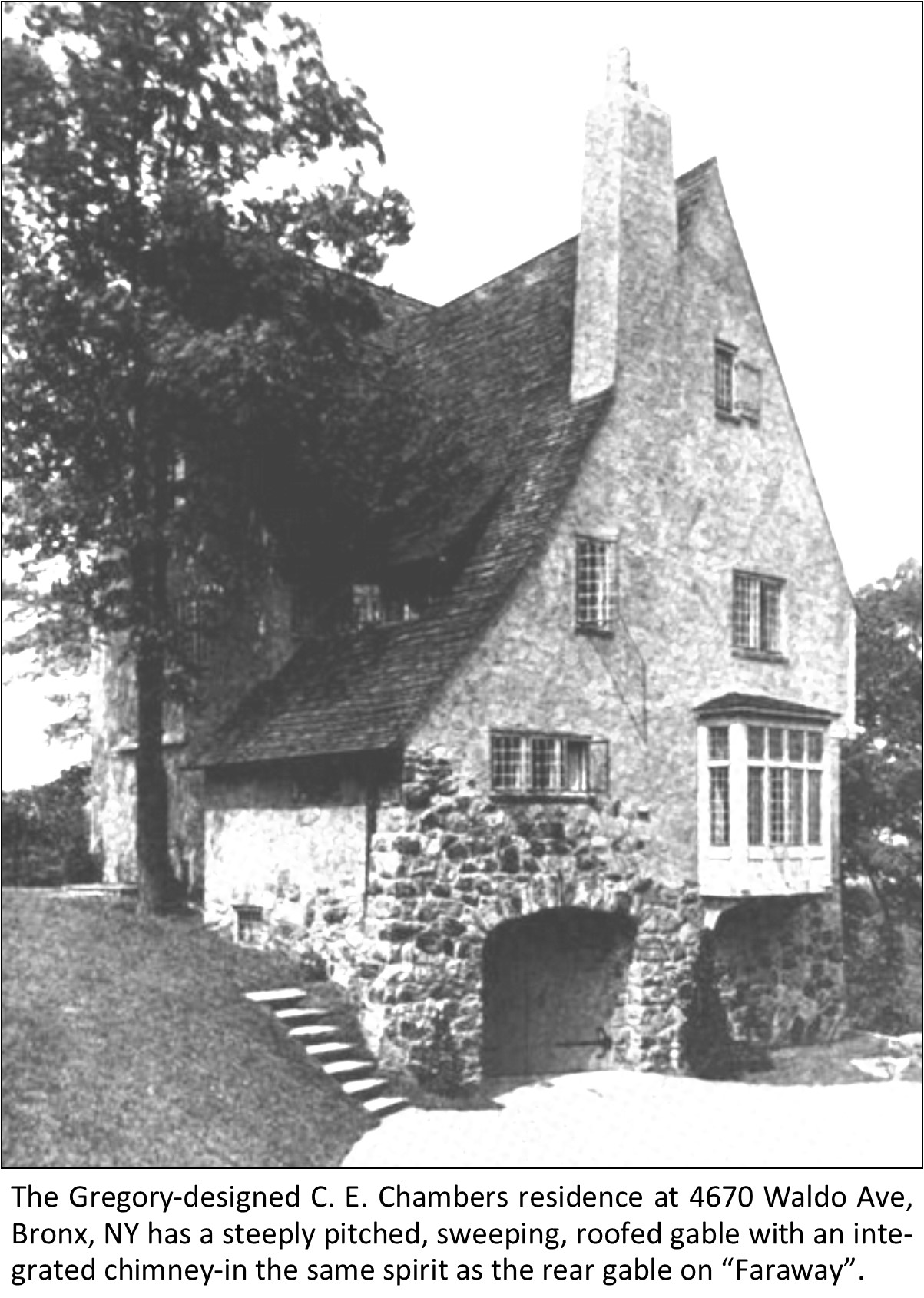

Looking at the rear façade of “Faraway” we see another typical Gregory detail-a gabled wing with a steeply pitched roof which sweeps down lower on its south side ending in a delicate curve. This roof profile, combined with an integrated chimney, is a detail that Gregory often used on his Medieval Revival houses. One look at the this roof profile on “Faraway” brings to mind the picture of a storybook house from a children’s fairytale or storybook!

A comparison of the interior features of “Faraway” with those of the Clough cottages show many similarities, the most noticeable feature being their living room fireplaces. All three fireplaces have a stone surround, tile hearth, and a simple oak mantle on stone brackets. All three houses also have plastered interior walls (with eased edges) with simple wood trim in their principal rooms. Arched openings are also shared by all three houses.

The Storybook-style English Cottage, known as “Faraway”, owes it picturesque design to architect Julius Gregory. Whether or not Gregory was the architect of record or not, seems to me to be a moot point, as it is clear that the details, massing, and overall design of “Faraway” are those of Julius Gregory, either from his own hand or from someone who successfully mimicked his style. I’m sure that Julius Gregory would be proud to claim this as his design, and would be happy to know (as we are) that another one of his “old English cottages” not only still survives, but is now being lovingly restored to it’s original enchanting and picturesque appearance.

Photo Credits:

“Faraway” oval vignette: Courtesy of Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

“Faraway” vintage photo: Courtesy of Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

Photo of Julius & Lovrein Gregory: from Nicole Gregory (granddaughter of Julius Gregory, daughter of Julius “Jules” Gregory, Jr.).

Clough Cottages-Streetscape looking northeast– photo by Author.

“Faraway” roof photo: by Author.

7 Kimberly roof photo: Courtesy of Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

“Faraway” jettied bay photo: by Author.

5 Kimberly Avenue jettied bay photo: by Author.

7 Kimberly Avenue jettied bay photo: Courtesy of Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

Photo of Alice Delorme Taylor House: from Fieldston Historic District Designation Report, Volume 1, (New York Landmarks Preservation Commission, January 10, 2006) page 69.

Sidney Sonn Residence: from The Architectural Record, Volume 62 Number 5, November 1927, page 440.

“Faraway” foundation photo: by Author.

5 Kimberly Avenue foundation photo: by Author.

7 Kimberly Avenue foundation photo: Courtesy of Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

“Faraway” rear facade photo: Courtesy of Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

C.E. Chambers residence –Advertisement for: International Casement Co., Inc.- Yearbook of the Architectural League of New York and Catalogue of the Thirty-Sixth Annual Exhibition, Volume 36, by Architectural League of New York, 1921, page 236.

“Faraway” foundation photo: Courtesy of Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

7 Kimberly Avenue fireplace photo: Courtesy of Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

5 Kimberly Avenue fireplace photo: photo courtesy of owners, Max & Wendy Haner.

[1] 12/22/1922 J. M. & Leah Chiles to L. H. Moore LOT 33 BK 3 P 11 Db. 265 / 352.; 08/30/1923 J. M. & Leah Chiles to L. H. Moore LOT 34 BK 1 P 54 Db. 276 / 34. Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[2] 07/21/1925 E. W. & A. G. Grove to L. H. Moore LOT 84 BK 154 P 192 Db. 301 / 539. Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[3] The Montgomery Advertiser, Montgomery, AL, July 7, 1926, page 8.

[4] Asheville, North Carolina City Directory, Ernest H. Miller Press, Asheville, NC 1926, page 546.

[5] 03/16/1926 L H & Sarah J Moore to Nancy Merrimon Erb LOTS 33 34 BK 3 P 11 Db. 341/4. Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

[6] Arrol Gellner and Douglas Keister, Storybook Style: America’s Whimsical Homes of the Twenties. (New York, NY: Viking Studio, 2001).

[7] House and Garden’s Book of Houses: Containing Over Three Hundred Illustratioons of Large and Small Houses and Plans, Service Quarters and Garages, and Such Necessary Architectural Detail as Doorways, Fireplaces, Windows, Floors, Walls, Ceilings, Closets, Stairs, Chimneys, Etc. (1920). United States: C. Nast & Company.

[8] See “The Clough Houses: Architect Julius Gregory’s English Cottages”-by Dale Wayne Slusser. htps://psabc.org/the-clough-houses- architect-julius-gregorys-english-cotages/

[9] “On the Charm and Character of the English Cottage,” by Julius Gregory. Architectural Forum, Volume 44 (March 1926), 147–52.

[10] Ibid, page 148.

[11] Ibid, page 149.

[12] Creating a New Old House, by Russell Versaci. (Newtown, CT: Taunton Press, 2003) page 12.