By Dale Wayne Slusser

As the ravages of the “Great War” began to fade and the post-war prosperity of the early 1920s dawned, those U. S. servicemen and women who had served overseas, began to replace their images of the horrors of war with the more pleasant memories of the peaceful and picturesque villages which they had come across in England and Europe. The result was a proliferation of house designs based on the idyll of English and European cottages, manors, and farmhouses. Not surprisingly, when builder/developer, Lieutenant Allison C. Clough, who had served in France with the 5th Battalion of the 20th Engineer Regiment (Forestry), decided to build his two speculation houses on the newly opened Kimberly Avenue in Mr. Grove’s high-class development, he commissioned notable New York architect Julius E. Gregory. Gregory, who had also served overseas, was not only designing in, but beginning to popularize, what would be later called Medieval Revival Style homes- based on the influences from British and French medieval houses.

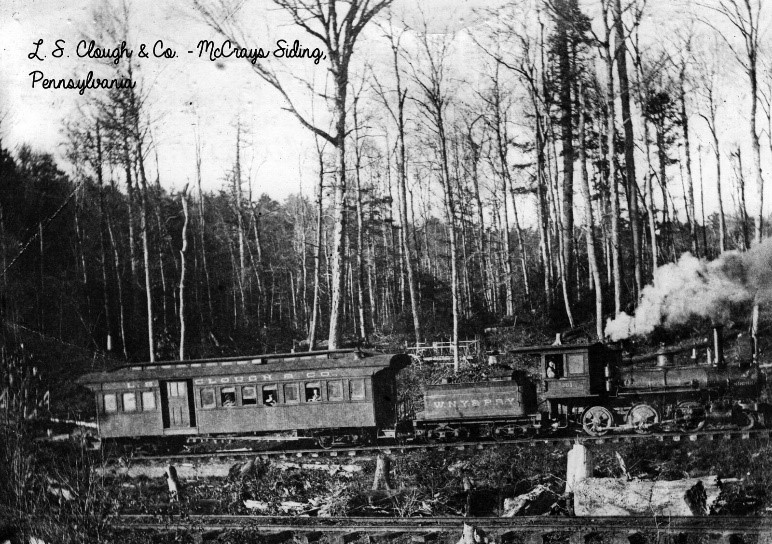

Allison Cady Clough (pronounced Cluff-like “rough” and “tough”) was born on January 21, 1893 in Union City, Pennsylvania to Levi S. Clough and his second wife, Alice Cady Church Clough. Sadly, Alice died on January 30th, just one week after giving birth to Allison. No doubt she died of complications from childbirth, and I suspect that baby Allison was named in her honor (Alice’s-son?). However, Allison, along with his half-siblings (from his mother’s first husband) was raised and well cared for by his father and stepmother, Dora Davis Clough (Levi married Dora in 1894). “L. S.” Clough, Allison’s father had become wealthy in the timber and lumber business, owning large tracts of timber and operating several saw and wood products (handles & shingles) mills in Marienville, PA, and Rome, NY.

In January of 1902, L. S. Clough and his wife Dora came to Asheville “for the winter” and rented a log bungalow on Hillside Street between Merrimon Avenue and Liberty Street.[1] In March, Allison’s half-sister, Marion Clough was born while the family was wintering in Asheville. L. S. Clough decided to establish a permanent winter residence in Western North Carolina, and so in June of 1902, he purchased an 86 acre farm in Transylvania County near Brevard, NC. (the property is now a housing development named Glen Cannon). For the ensuing decade, the Clough family continued to divide their time between their homes in Brevard and Pennsylvania, often leasing houses in Asheville during the winter months. Not surprisingly, when it came time for Allison’s formal education, he was enrolled at the Asheville School. Asheville School, which is still in operation, was founded in 1900 by Charles Andrews Mitchell and Newton Mitchell Anderson. Allison Clough graduated from Asheville School in 1912, and the following year, in August of 1913, he married local Ashevillian, Ellen R. Smathers, the son of Mr. & Mrs. George H. Smathers.

Immediately following their wedding Allison and Ellen moved to Oregon where Allison had been sent to manage his father’s newly acquired timber business. In July of 1913, a month before the wedding, it was officially announced that L. S. Clough and William Smearbaugh, both from Warren, Pa. had formed the “Penn Timber Company” in Oregon, and that they had acquired a 31,000 acre tract of timber in Eugene, Oregon on which they were establishing timbering and saw mill operations. From 1913 until the outbreak 1917, Allison and Ellen lived in Oregon, Pennsylvania, New York, Brevard and even stints back in Asheville, alternating between locations of the Clough lumber operations. In fact, the Cloughs came back to Asheville in 1914 for the birth of the first son, Allison Cady Clough, Jr.

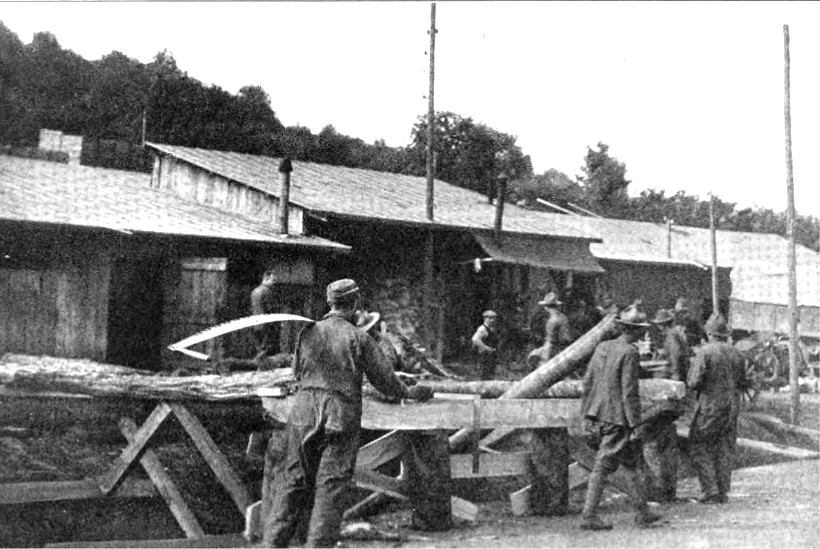

In December of 1917, as the war in Europe was raging, Allison Clough enlisted in the 13th Company of the 5th Battalion of the 20th Engineer Regiment (Forestry). After a few weeks of training at Fort Belvoir in Washington, DC, in January 1918, Lieutenant Allison C. Clough sailed for France.[2] “The 13th Co. was sent to the village of Brinon-sur-Sauldre, Cher, where they erected an American sawmill of 10,000 foot capacity.”[3] Brinon-sur-Sauldre is a community in the Cher department in the Loire Valley region of France. The 20th Engineers not only felled trees for timbers and firewood, but they also milled wood products such as “100 ft. piles for docks at the base camps”, wood planks for the boardwalks at the bottom of trenches and for artillery roads, railroad ties, timbers for bridges and trestles, stakes for fencing, and timbers and boards for barrack building.

Lieutenant Clough was discharged from the Army at Fort Jackson, SC in June of 1919. After a brief stay in Asheville, visiting his in-laws, Allison and his family established their primary residence in upstate New York in the Rome/Uttica area, where Allison served as a lumber merchant/salesman at his father’s mill in Rome, NY. The Cloughs continued to visit Asheville over the next few years, and then in 1922 Allison decided to establish a secondary residence in Asheville. In August of 1922, Allison Clough purchased the former summer residence of William Jennings Bryan in Grove Park (107 Evelyn Place), along with several contiguous lots.

Shortly after purchasing the Grove Park lots, Clough decided to develop his property. He opened a service alley through the middle of the lots, starting at Kimberly Avenue, directly behind the Bryan house. Since the lots were sloped from front to back, the service alley served rear basement garages in the Bryan house and the new houses as well.

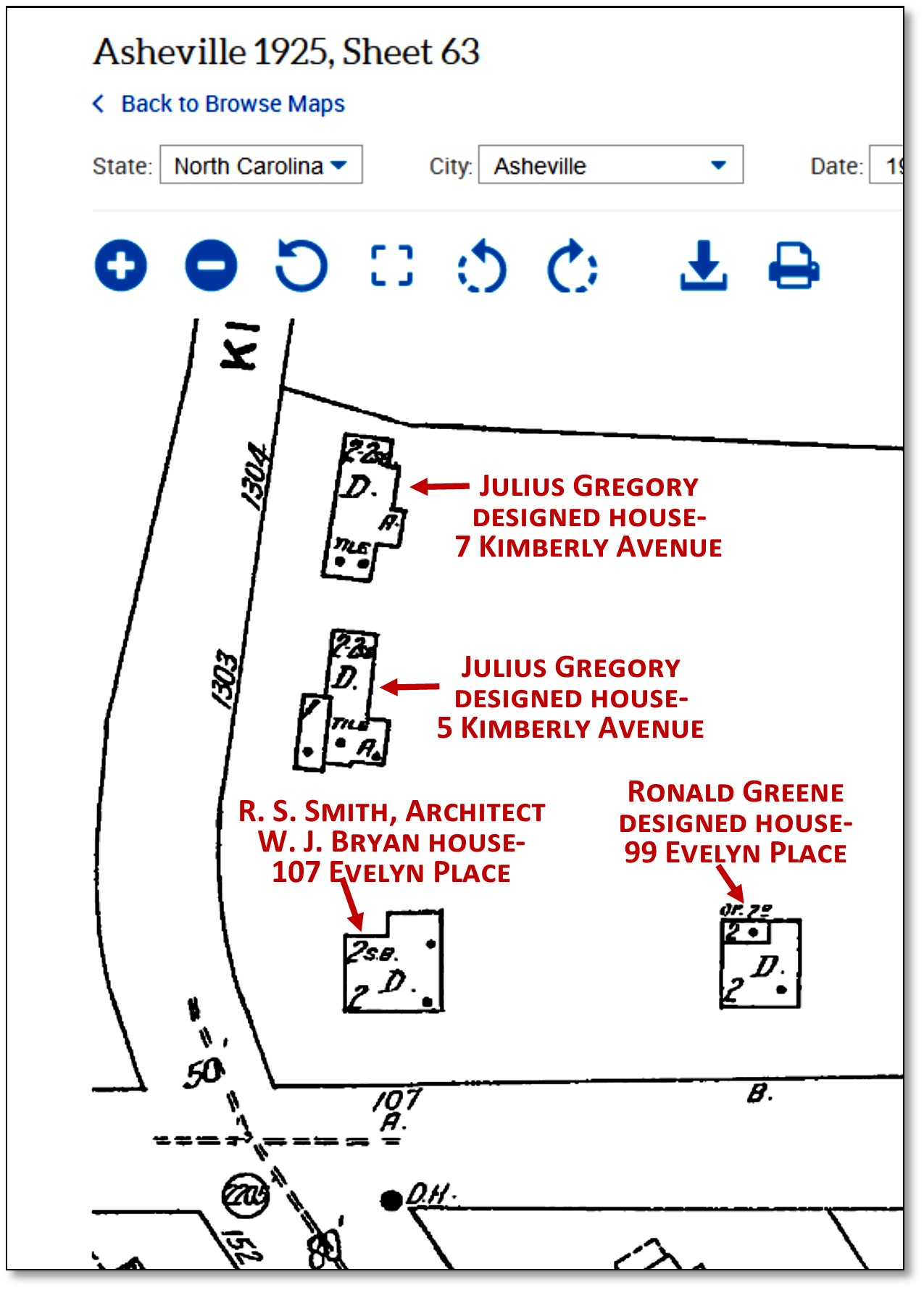

For the adjacent lot, to the east of the Bryan house, Clough hired local architect Ronald Greene to design a two-story New England Colonial styled frame house (99 Evelyn Place).[4] However, for the two lots carved from the Bryan house’s rear yard, Clough had something special planned. Instead of using a local architect, Clough hired a New York architect named Julius E. Gregory, who by 1921, just four years after the Great War, was becoming famous for his English and French inspired house designs, reminiscent of those that both he and Clough no doubt experienced while serving overseas. The location of the Clough cottages behind the W. J. Bryan house shows in a circa 1923-24 aerial photo (below) taken shorty after their construction, as well as on the 1925 Sanborn Fire Insurance map.

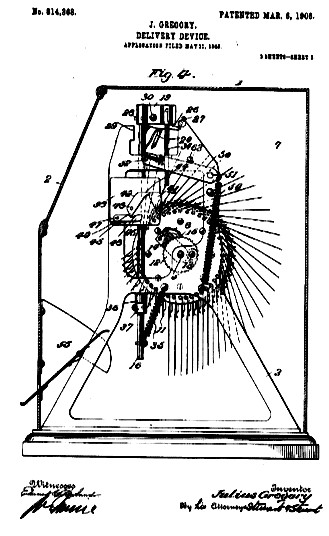

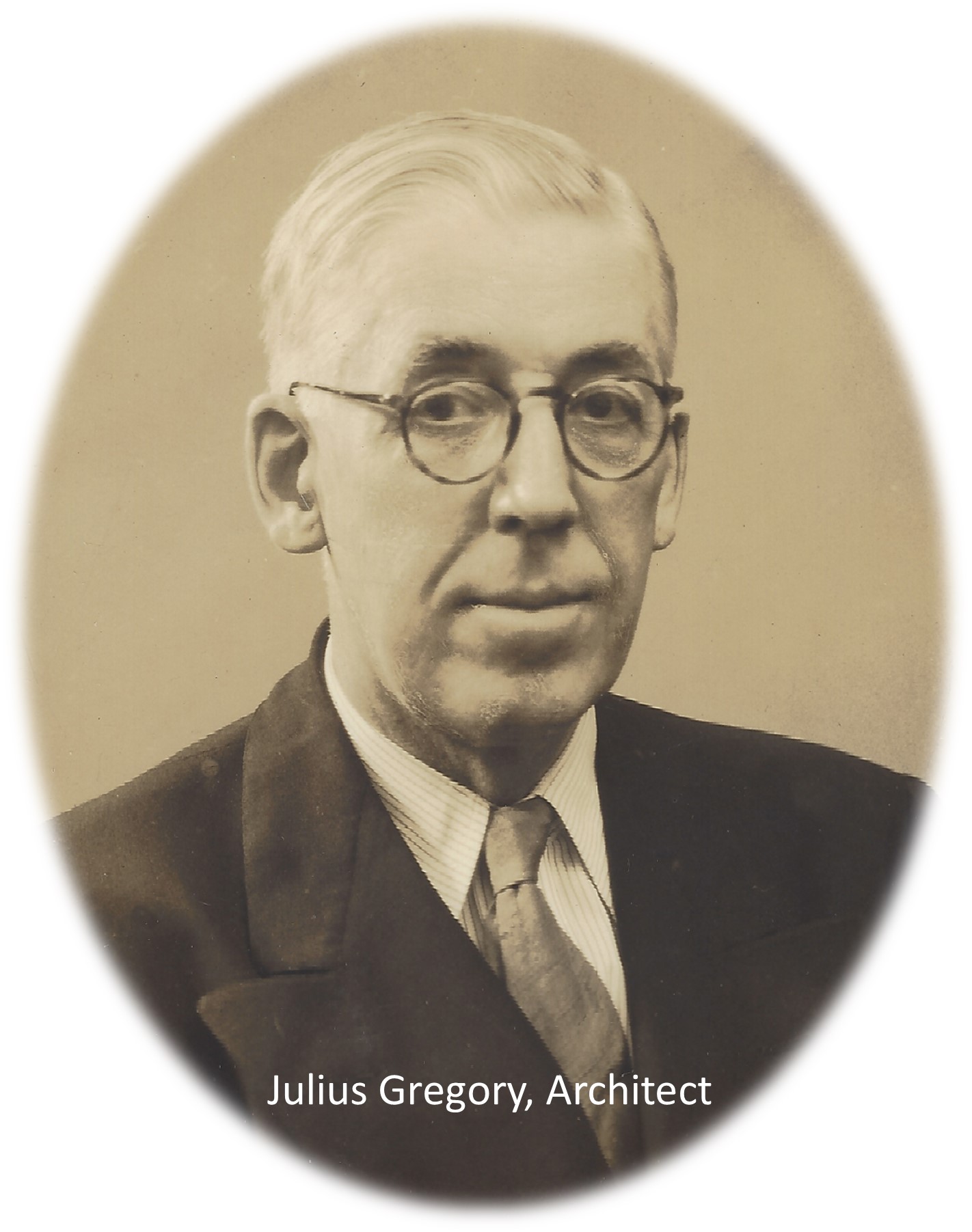

Julius Eugene Gregory was born in 1875 in Sacramento, CA to Eugene Julius Gregory and his wife Emma. Julius graduated from the University of California at Berkley in 1897 with a degree in Mechanical Engineering. But prior to his graduation, in 1894-95, Julius, along with his father, invented a photo machine to be used by the railway company to insert an identification photo on each ticket. Their ingenious invention contained a camera, and when the ticket was inserted into the machine it took an instant photo of the ticket purchaser, and through a series of emulsion cups the photo was “developed” onto the back of the ticket, and in 45 seconds or less the ticket with a photo of the purchaser embedded on to it would emerge from the machine.[5] This was the forerunner of the photo booth and the photo-copier.

In June 1899, Eugene and Julius went to New York to obtain a patent for the new machine. From New York, in June of 1899, father and son boarded the S. S. Pretoria[6] bound for Germany-with stops in Plymouth, England and Cherbourg, France. In England, they stayed long enough for Julius to apply for a British patent for his new apparatus[7]. The patent gives Julius’ address as 53 Chancery Lane, London, which is an office building, and I believe to be the address of a patent agent through whom the Gregorys worked to register the patent. Julius’ passport said that he was planning to be out of the US for three months, so no doubt Julius had time for sightseeing in between his business dealings, and probably observed the quaint old cottages and village houses along the way from the port of Plymouth to London. Perhaps it was on this trip that Julius Gregory first became enamored with the quaint but attractive houses that he observed in the English towns and villages that he visited. Eugene and Julius later sailed on to Germany where, through a German patent agent, they obtained a German patent as well, before returning home.[8]

Shortly after their return from England and Europe, Julius’ father sent Julius to New York City to work on the design development and further patent work for their new invention, as well helping other inventors to obtain patents for their inventions. One of these was a “Pyrographical Tool”, designed by William Henderson Scott, was a forerunner to the modern-day woodburning pen, except that it used gas heat instead of electricity. The pyrographical tool patent was assigned by Scott to Eugene and Julius Gregory and Thomas Wiseman. The patent was obtained in 1900. In 1906, the final revised patent and improvements to the photographic machine were completed, so Julius along with others, including Thomas Wiseman, and chemist Julian Florian incorporated the “Photo Machinery Company” and began manufacturing his photographic machine. The first manufacturing facility was established in Sacramento, but shortly thereafter moved to New York City. By 1907, Julius was managing his new company in New York City and living at the Vandyke Studios building at 939 Eighth Avenue.[9] The Vandyke Studios was an urban “artists colony” where artists lived and worked together, each having their own room and studio. Clearly, Julius Gregory the engineer, had more artistic leanings, making him better suited for being an architect than a mechanical engineer. Around 1911 or 1912 his life took a dramatic change, following a short-lived first marriage[10], Julius the engineer/inventor/manufacturer began practicing architecture.

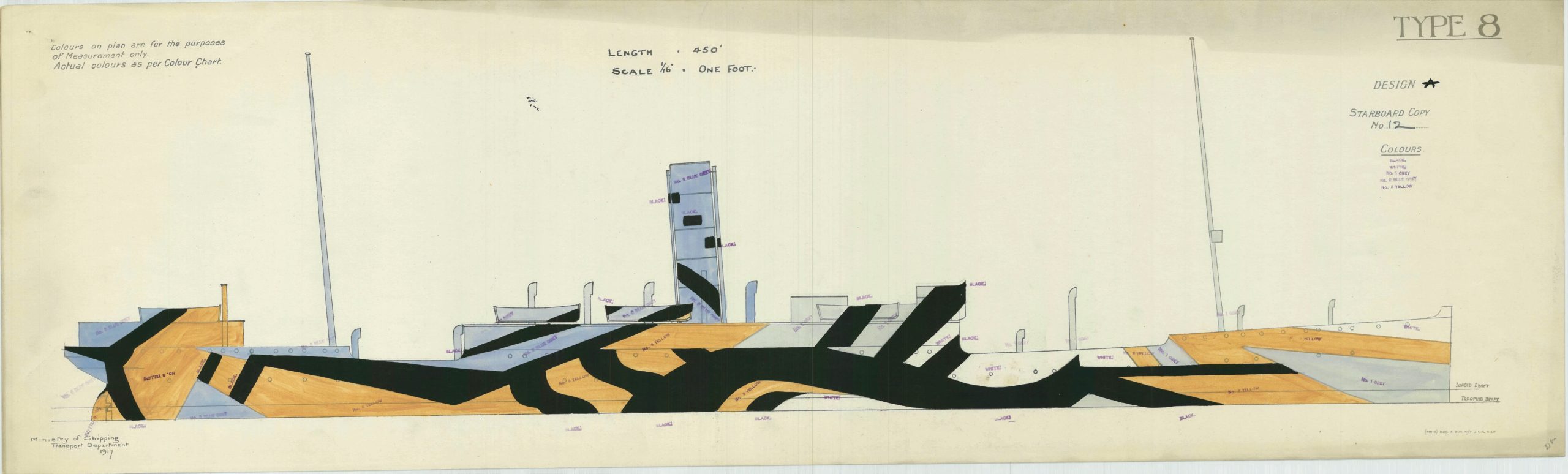

Julius Gregory’s new career was quickly interrupted by the onset of the Great War. In July of 1918, Gregory, who was then 43 years old, was commissioned by the U. S. Navy, as the District Camoufleur (camouflage artist) for the New York Harbor. All the ships leaving the harbor had to be painted with camouflage to protect them from enemy attack. In September of 1918, Julius married artist Mary Lovrein Price, and the following month he boarded a ship bound for England. He was being sent to train under British Illustrator cum Royal Navy Officer Norman Wilkinson. Wilkinson had developed a series of geometric “dazzle” camouflage schemes which instead of hiding a large ship, as ground camouflage was designed to do, his schemes were designed to confuse the eye, so that an enemy could not tell what they were seeing.[11] Dazzle camouflage “was based on the theory that, just like stripes on a zebra and spots on a cheetah, stripes and odd patterns on a battleship would make it harder to target by breaking up its outline.”[12] Gregory was sent to train under Wilkinson at the Royal Academy of Arts at Burlington House in London. Perhaps Julius revisited the English towns and villages that he had visited in 1899. Not surprisingly, when he resumed his architectural practice after the war, his specialty became designing English-revival styled residences.

Although Allison Clough, in his lumber merchant business, may have met architect Julius Gregory in New York City in the early 1920’s where they were both living and working, I have not been able to find any evidence to support that supposition. However, it’s highly likely that Clough had read about and observed Julius Gregory’s work which was being published in the local newspapers, such as the half-page spread, “Suggesting a Leaf from a Medieval Sketchbook: Home of C. E. Chambers, Illustrator at Fieldston, Has all the Quaintness of the Norman Influence Coupled With the Mellowness of the Old English Manor House”, which along with printed pictures, published in the Sunday, July 10, 1921 edition of the New York Herald.[13] Clough may have even visited Fieldston, a privately owned affluent neighborhood in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, which was populated by a disproportionate number of Julius Gregory-designed homes.[14] Gregory’s homes were also widely published in the architectural journals and house magazines of the day, and two houses were even featured in a 1920 book of House & Garden homes.[15]

Sometime in 1922, Allison Clough commissioned Gregory to design two different but complimentary English style houses for Clough’s two sloped lots along Kimberly Avenue. Both houses were designed to be two-story at the street level with a full walkout basement opening onto the lower rear yards. And both were designed with textured stucco-finished exterior walls with brick windowsills. Each cottage also sported a steeply pitched roof, although the house at 5 Kimberly was designed with an end-gabled main roof, whereas the house at 7 Kimberly was designed with a hipped main roof.

“The Clough Houses are now open for inspection…,” announced a July 3, 1924 advertisement in the Asheville Citizen Times.[16] A subsequent advertisement, just three days later, described one of the Clough houses as designed “after the manner of manor houses along the Thames…”.[17] This description which seemed a bit misleading, according to my knowledge of houses in Britain, prompted me to take a closer look at the design and possible design antecedents for these unique houses. The two houses were designed in the Medieval Revival Style, which was based on Medieval houses in England, France and Germany. Certainly, the Clough houses were based on English Medieval houses, but were they designed “after the manner” of medieval “manor” houses? In Medieval England, a “manor” was the estate of a wealthy Lord, who lived in the Manor house, the seat of the estate. Manor houses were always large and usually grand compared to the houses of the workers and tradesmen who lived in humble farmhouses and cottages on the estate or in the surrounding farms and villages. The Clough houses are more closely akin to the humbler farmhouses and cottages which still dominate the rural landscapes and village lanes of England, however more on that later, when we will look at possible British design antecedents. But, first let us look at the Clough houses as what they really are, the creations of architect Julius Gregory.

“The English type of house as developed in this country constitutes one of the most interesting and picturesque forms of our domestic architecture,” wrote architect Julius Gregory himself, in his article, “On the Charm and Character of the English Cottage” published in the March 1926 edition of the Architectural Forum.[18] In this article we are fortunate to get a glimpse into Gregory’s design philosophy and perspective on designing “English houses” for twentieth-century Americans. “The old cottage in England, usually a little farmhouse, low lying, and with a background of trees, a well-kept-garden, and flag walks,”, writes Gregory, “is the protype of our English cottage.”[19] The Clough houses, even today, evoke all these images of “the old cottage in England”, with their “well-kept front gardens” and “flag walks”, partially hidden behind their low stone wall along Kimberly Avenue.

Julius Gregory’s Medievel Revival houses reveal that his design philosophy was deeply influenced by the British Arts & Crafts Movement, which looked back to the Medieval period for their inspiration. British proponents of the Arts & Crafts Movement, such as architects William Morris and C. F. Voysey looked back to the pre-industrial age Medieval craftsmen who took such pride and care in plying their craft that craftsmanship was elevated to an art! Commenting on old English homes, Gregory writes, “The old houses were built to endure, were structurally sound, and were wrought by the hands and souls of craftsmen whose traditions had been carried down from family to family, and whose pride of workmanship, and understanding of materials were parts of their lives.”[20] Why is it that these simple unadorned houses built of natural materials like stone, brick, stucco, and wood timbers are so appealing to us? “The satisfying feeling of texture predominates,” answers Gregory, and “texture, the elusive quality of a surface which makes it pleasing to the eye, permeates our picture of the old work. And it pleases because it is the product of the understanding hand of the craftsman, done in humble reverence and with a feeling for his material. There is no striving for effect, nothing more than a straight-forward use of wood, brick, stone, and mortar in simple and direct way, resulting in a surface that is hand-made, beautiful to look at, and one that will be satisfying through all time.[21] This simple use of natural building materials and texture are certainly hallmarks of the Clough houses, as displayed on the exterior walls by the use of textured stucco contrasted only by brick window sills and simple wood door and window frames.

“Another feature of these old English cottages, and hardly less important than that of texture,” says Gregory further, “is simplicity of mass; large restful areas of wall and roof with spare spotting of openings; the windows grouped together and not many in number; the simple doorways, usually framed in oak and with solid aged doors.”[22] This “simplicity of mass” and “large restful areas of wall and roof with spare spotting of openings” shows on both cottages, but is especially evident on the cottage at 7 Kimberly Avenue, with it’s simple box-like massing topped by a long expanse of hipped roof, unbroken except for one barely raised dormer on its south wing (obviously made to appear to have been a later addition).

Gregory, commenting on the roofs of old English cottages, writes, “The passing of time has left its imprint on these, the sagging lines of the old ridges and rafters…”[23]. Gregory used an artistic artifice, just like the stage-set designers used on their “story-book cottages”, on the roofs of house at 5 Kimberly Avenue. To give the appearance of age, Gregory flared the ends of the roof ridges upward, so that when viewed from the ground it would have the appearance an aged sagging roof.

Gregory also reveals his approach to the design and detailing of the interiors of his English cottages. “Inside the old house,” writes Gregory, “the same qualities of structural honesty, simplicity, and directness, and softness of texture prevail.”[24] We see this simplicity and softness of texture on the design of the interiors of the Clough cottages. This is especially evident in the living rooms of each cottage, where their plain plastered walls with softened edges at the doorway and window openings, contrasts with the warm light-oak flooring. Along with the simple wood mantles and the stone-surround fireplaces with their tiled hearths, Gregory seemed to capture those same qualities of simplicity and “softness of texture” of the old English cottages that he sought to emulate.

All revival-style homes, be it Colonial Revival, Spanish-Revival or Medieval-Revival are seldom replications of specific old houses, but rather revival architects and designers use details and materials prevalent in the old houses to capture what Gregory calls “the spirit of the old work”[25] For this reason, I thought it would be interesting to take a look at possible English antecedents from which Gregory may have formed his design philosophy for his Medieval-Revival homes, specifically those which may have contributed to the design and details of the Clough cottages.

I had first thought that the steeply pitched hipped roof on the house at 7 Kimberly Avenue was probably designed to mimic the thatched roofs of old English cottages, however, a study of traditional vernacular houses in Britain, shows that the roof, as well as the general massing of the house, can be traced back to the medieval “Wealden Hall House” of South-east England. “Among the earliest substantial dwelling houses for people of the yeoman farmer class which survive [in England] are those which are usually called Wealden Houses because they were first recognized on the Weald of Kent and Sussex.”[26] A “yeoman farmer” in Medievel Britian, was a middle class person (between gentry and commoners) who owned and farmed his own land. Wealden houses, usually wholly of timber-frame construction, formed a simple rectangle on the first floor and contained a center hall (open to the roof) flanked on each end by service rooms.

A distinctive feature of Wealden Hall houses, is the second floor jettied front bays on each end. Although the Clough cottages do not have the front jettied bay configuration of the Wealden houses, the cottage at 5 Kimberly does have a second-floor projecting faux timber-framed bay above the rear-facing dining-room, giving nod to it. The cottage at 7 Kimberly featured a rear gabled wing with a faux timber-framed first and second floor. This wing has recently been extended during a recent renovation.

One additional feature of the Clough cottages which I believe to have its roots in the Wealden House is their living rooms, which like the “hall” of the Wealden house are not only the center room in each cottage, but they also stretch from the front wall to the rear wall with front & rear windows. Of course, the Clough cottage living rooms are not open to the second story, as in the original Wealden houses, however, it is known that old Wealden house halls were often “floored-over” on the second story in later generations.

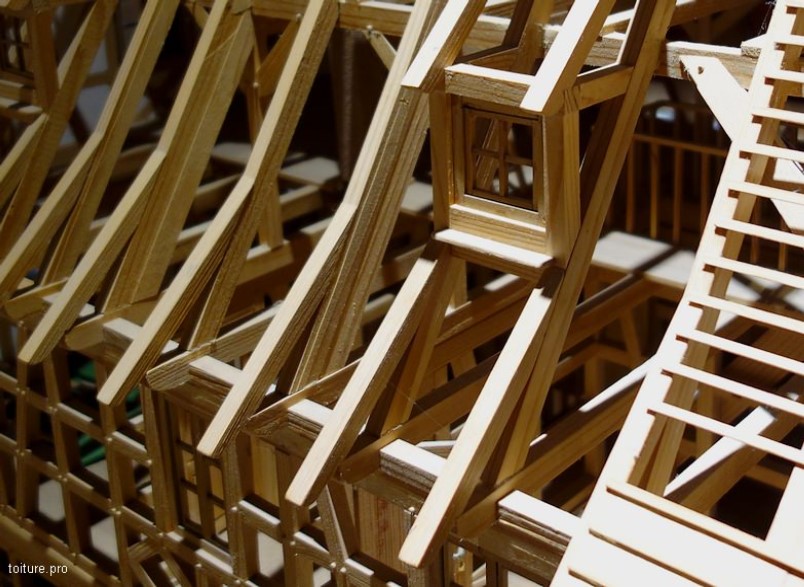

One specific feature of the Clough cottages which has piqued my interest are the flared or “bellcast” roof eaves. I assumed that they had derived from old English cottages but was not sure of their exact origin or purpose. A study of old Medievel English house construction shows that they are called “sprockets” in England, but more appropriately called “coyau” in French. Coyau is a change of pitch of the roof at the eaves, and is formed with a small auxiliary rafter tail (Coyau derives from “tail”) which is nailed to the top of each rafter to extend out over the wall to create an overhang, negating the need for guttering. They were developed from Medieval timber-framing where the framed rafters ended on top of the wall- framing, necessitating the use of a coyau to extend the roof beyond the walls. The following photos show how coyau were used on timber-framed construction, and how they are still used in England and Europe on masonry walls as well.

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the Clough cottages is their expansive stuccoed exterior walls. These also have British antecedents, although in Britian it is called “render” or “plaster”. This type of simple exterior finish has ancient roots and was first used in a “wattle and daub” building system. Wattle and daub is a “method of constructing walls in which vertical wooden stakes, or wattles, are woven with horizontal twigs and branches, and then daubed with clay or mud. This method is one of the oldest known for making a weatherproof structure. In England, Iron Age sites have been discovered with remains of circular dwellings constructed in this way, the staves being driven into the earth.”[27] In England it became prevalent during the Medieval period when it was used to fill-in the spaces between the timber-framing. Later render (stucco) was commonly used to cover old masonry walls to protect the deteriorating brick or stone. It was also used on renovations and additions where it would have been impossible or cost prohibitive to match the original brick or stone. Pebbledash, a later form of render which included small stones to give a rough texture (hence, it is also called rough-cast) became very popular as an inexpensive exterior finish. Suffice it to say, that stuccoed or “rendered” houses are and have been prevalent in England for centuries. A row of early eighteenth-century cottages on Church Green, St Peter’s Street, in St Albans, Hertfordshire (see photo) with their simple stuccoed exterior facades, are among thousands of examples, of the charm and quiet domesticity that this finish can evoke. Architect Julius Gregory applied this ancient exterior finish onto “hollow tile” walls on the Clough cottages. “Hollow-tile” are terracotta blocks, similar to concrete/cement blocks, that were especially popular during the early to mid-twentieth century for building “fire-proof” (now more accurately called fire-resistant) buildings. Gregory used is it often in his houses.

Speaking of Gregory’s use of a “modern” material such as hollow-tile, it’s important to note that although Gregory designed the Clough houses to appear as if they had been built during the Middle Ages, he not only used modern materials where necessary, but he also designed them to meet the “modern” needs and wants of twentieth-century homeowners. Each had modern electrical, plumbing, and heating systems. But the most evident feature which denoted their accommodation to modern living are their basement garages. Of course, Clough cleverly hid the garages, and accompanying driveways, in the rear basement façade of each house. The house at 5 Kimberly retains its original garage. However, the house at 7 Kimberly recently enclosed its original garage as part of an extensive renovation, although it has been replaced with a two-car garage cleverly built into the ground next to the house underneath the side lawn.

The Clough cottages remain today as a testament to architect Julius Gregory’s proficiency in designing houses that not only continue to stand the test of time, but still continue to meet the needs of modern-day homeowners while retaining the charm and aesthetic of “the old cottage in England”.

Photo Credits:

Clough cottage vignette photo– by Author.

L.S. Clough Company train postcard photo- Collection of the Author.

20th Engineer Sawmill in France– “The American Lumberjack in France” – By Lt. Col. W. B. Greeley. https://foresthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Greeley.pdf

Ronald Greene designed house at 99 Evelyn Place– Buncombe County Tax records,

https://prc-buncombe.spatialest.com/#/property/964956177700000

1923 Photo of Clough houses on Kimberly Avenue- Image B410-XX, North Carolina Collection, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

1925 Sanborn Map-from NC Live-cropped and labeled by author.

Julius Gregory’s “Delivery Device”-Patent- US814368A dated 1905, https://patents.google.com/patent/US814368A/en?assignee=%22Julius+Gregory%22&oq=%22Julius+Gregory%22

Julius Gregory, Architect– from Nicole Gregory (granddaughter of Julius Gregory, daughter of Julius “Jules” Gregory, Jr.).

Dazzle Scheme– RG; 19, Camouflage Design Drawings for U.S. Navy Commissioned Ships, U.S. Merchant Ships and British Ships. Shown above are the design templates for Type 8, Design A, Starboard Side (NAID 56070607). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/56070819

Article of C. E. Chambers residence– New York Herald, New York, NY, July 10, 1921, page 47.

Cottages-Streetscape looking northeast– photo by Author.

Photos of 5 and 7 Kimberly Avenue with front gardens– photo by Author.

South Elevation of 5 Kimberly Avenue– photo by Author.

Photo of 7 Kimberly Avenue – front facade– photo by Author.

Photo of roof of 5 Kimberly Avenue– photo by Author.

Photo of living room of 5 Kimberly Avenue– photo courtesy of owners, Max & Wendy Haner.

Photo of living room of 7 Kimberly Avenue– photo courtesy of Preservation Society files.

Wealden Hall House- “English: Coggers A Wealden Hall house on Walkhurst Road.”, photo by David Anstiss, Date: 14 January 2010

– geograph.org.uk – 1709598.jpg

Photo of 5 Kimberly Avenue jettied timber-frame– photo by Author.

Photo of 7 Kimberly Avenue jettied timber-frame– photo courtesy of Preservation Society files, cropped by Author.

Coyau on Timber-frame- Model source: Ecomusée d’Alsace- https://toiture.pro/lexique/coyer-coyau.html

Coyau on modern masonry wall- Wrath Of Gnon @wrathofgnon , Twitter post, Mar 6, 2019.

Stuccoed Houses on Church Green– TL1407 : Cottages on Church Green, St Peter’s Street, near to St Albans, Hertfordshire, Great Britain. Photo by: Alan Murray-Rust. https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/4745535

Photo of 7 Kimberly Avenue – rear façade– photo courtesy of Preservation Society files.

[1] Asheville Daily Gazette, Asheville, NC- May 30, 1902, page 2.

[2] Asheville Citizen -Times, January 3, 1918, page 6.

[3] “TWENTIETH ENGINEERS — FRANCE — 1917-1918-1919”, Portland, OR:Twentieth Engineers Publishing Association.

[4] Asheville Citizen -Times, July 3, 1924, page 19.

[5] “Anti-scalper Contrivance-How the Railroad Companies Hope to get Even”, The Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, CA, February 28, 1896, page 3.

[6] List of Cabin Passengers of the “Pretoria” (Hamburg-American Line, New York for Hamburg via Plymouth and Cherbourg), London American, Volume VIII, No. 12, page 9.

[7] Photographic Dealer, Volume VII, No. 38, July 1899, page 23. “12, 846. June 20, 1899, JULIUS EUGENE GREGORY, 53 Chancery Lane, London. Improvements in photographic apparatus.”

[8] Patentblatt herausgegeben von dem Kaiserl. Patentamt, Volume 24, C. Heymanns Verlag, 1900, page 1204.

[9] Where Greek Meets Greek-Greek Letter Societies, Compiled by W. J. Maxwell (New York: Alcolm Company, 1907) page 806. Julius Gregory is listed as: Iota; University of California, 1897; Mechanical Engineer, Photo Machinery Company; Residence, Van Dyck Studios, 939 Eight Avenue.

[10] Julius Gregory married Jessie Shuler Gregory in 1905, they legally divorced in 1912.

[11] See: Behrens, Roy R. “The Role of Artists in Ship Camouflage during World War I.” Leonardo, vol. 32, no. 1, 1999, pp. 53–59. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1576627

[12] Now You See Me, Now You…..Still See Me? Hand-Painted British Dazzle Camouflage Templates from WWI

September 5, 2017 by Amy Edwards, posted in Cartographic Records, Digitization, Military, Ship Plans, World War I. https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2017/09/05/now-you-see-me-now-you-still-see-me-hand-painted-british-dazzle-camouflage-templates-from-wwi/

[13] New York Herald, New York, NY, July 10, 1921, page 47.

[14] Of the over 250 houses in the Fieldston, NY Historic District, 42 of the houses were designed by Julius Gregory-and most of those were designed in the English/Medieval-Revival Style.

[15] House and Garden’s Book of Houses: Containing Over Three Hundred Illustrations of Large and Small Houses and Plans, Service Quarters and Garages, and Such Necessary Architectural Detail as Doorways, Fireplaces, Windows, Floors, Walls, Ceilings, Closets, Stairs, Chimneys, Etc. (1920). United States: C. Nast & Company.

[16] Asheville Citizen -Times, July 3, 1924, page 19.

[17] Asheville Citizen -Times, July 6, 1924, page 34.

[18] “On the Charm and Character of the English Cottage,” by Julius Gregory. Architectural Forum, Volume 44 (March 1926), 147–52.

[19] Ibid, page 147.

[20] Ibid, page 148.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid, page 149.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid, page 152.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Traditional Buildings of Britain: An Introduction to Vernacular Architecture, by R. W. Bunskill. (Butler and Tanner, Ltd.: London, England, 2004) page 46.