A substantial part of Asheville’s historic districts and neighborhoods are made up of houses and buildings built during the period from the 1880’s through to the 1920’s. The arrival of the railroad in 1880 caused a rapid and sizeable increase in the city’s population, which in turn resulted in Asheville’s first building boom of the 1880’s and 1890’s. Fortunately, with the influx of new residents, also came several new architects and contractors to handle the increased building demand. One of those new arrivals was an architect who was known mostly by his initials, “A. L. Melton”.

Allen Leroy Melton was born around 1850 in Morganton, North Carolina to Littleberry W. Melton and his wife Mary. The official North Carolina Death Records has Melton’s birthdate as December 23, 1848-BUT that’s incorrect as he is not listed on the 1850 census, and on the 1860 census his age is given as “9 yrs. old”. So, he was either born late in 1850, after the census taker had visited the family, or he was born in 1851. Littleberry Melton, a native of Virginia, had moved his family to Burke County, North Carolina in the 1840’s and by 1850 was working as a plasterer. At least two of Littleberry’s sons, including Allen took up the trade of plastering. In fact, in 1880, Allen is listed on the 1880 census as a 27-year-old “plasterer”, living with his widowed mother Mary, and his younger brother Andrew (who was also listed as a plasterer).[1] Concurrently, 1880 is also the year in which we find the first published reference to A. L. Melton. In April of 1880, Morganton’s newspaper, The Blue Ridge Blade, reported that the brick walls of “Judge Avery’s” new residence were completed, and that “the work reflects credit on the contractor, Mr. A. L. Melton, who is one of the best masons and plasterers in Western North Carolina”.[2] Importantly, the report also says that “Capt. A. L. Kayler[sp], the contractor for the wood work of the building will have it finished soon.”[3] This is important, because it shows that the use of a “General Contractor”, who managed the construction and hired the tradesman (who today we call subcontractors) was not yet a prevalent practice in the 1880’s. Interestingly, Capt. Kaylor (his name was mis-spelled in the news report) would later move to Asheville and work for Melton. Also, we see that Melton was working as a contractor and not an architect at the start of his career. Modern-day investigations of the Avery house, which is still standing at 408 N. Green Street in Morganton, indicate that this was a rebuilding/remodeling of an earlier house.

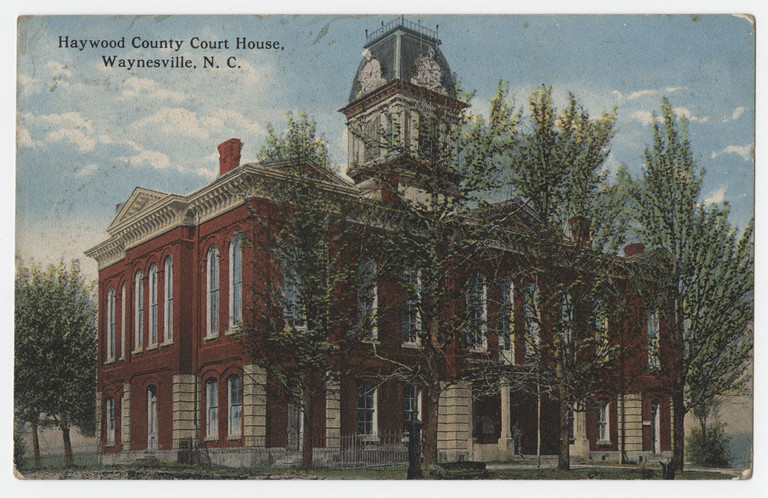

Noted architectural historian Catherine Bishir writes of Melton: “The earliest work cited in his obituary is the Haywood County Courthouse in Waynesville, an eclectic, towered edifice built in 1883-1884.”[4] Although I see no mention of that in the short obituary that I have found, I did find one newspaper article saying that Melton was living in Waynesville in 1883, but no mention of his work there. Also, Bishir further notes that, “An account of Bonniwell’s projects [George C. Bonniwell] and Melton’s obituary both cite the “Waynesville Courthouse” (Haywood County Courthouse) among their works.[5] My suspicion is that like on Judge Avery’s house, Melton was the contractor for the masonry and plastering of the courthouse. Whether that also entailed any design of the exterior, is hard to say.

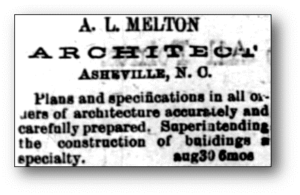

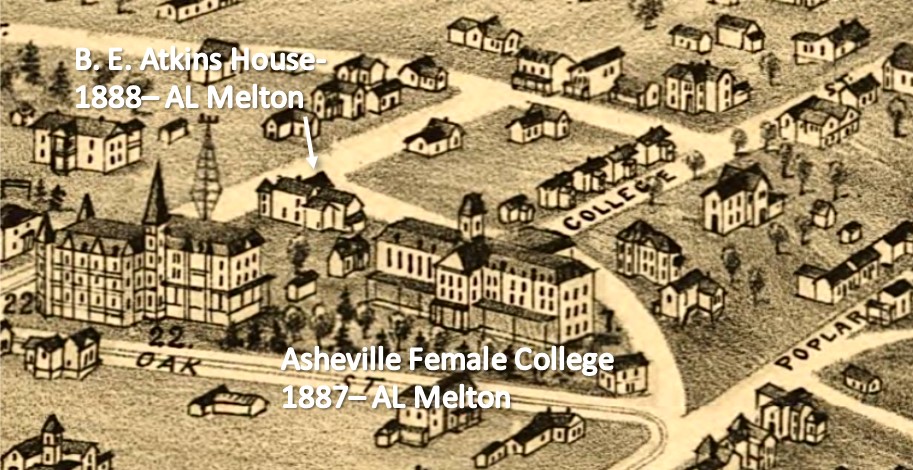

In September of 1886, the Asheville Advance, in a column simply titled “They Say”, announced “that Mr. Melton, an experienced architect will soon locate to Asheville”.[6] By May of 1887 he had established himself in Asheville and was fervently at work on several large projects. One of those was the design of a large four-story brick building for the Asheville Female College. This magnificent building, which sat near what is now the northeast corner of Charlotte and College Streets, was reported to have all under one roof: “study, classrooms, chapel, library, literary and missionary halls, studio and art gallery, museum, dining hall and bathrooms, double parlors and sleeping chambers for family, faculty and more than 100 pupils”.[7] The building also included a rooftop observatory and “680 feet of verandas”.[8]

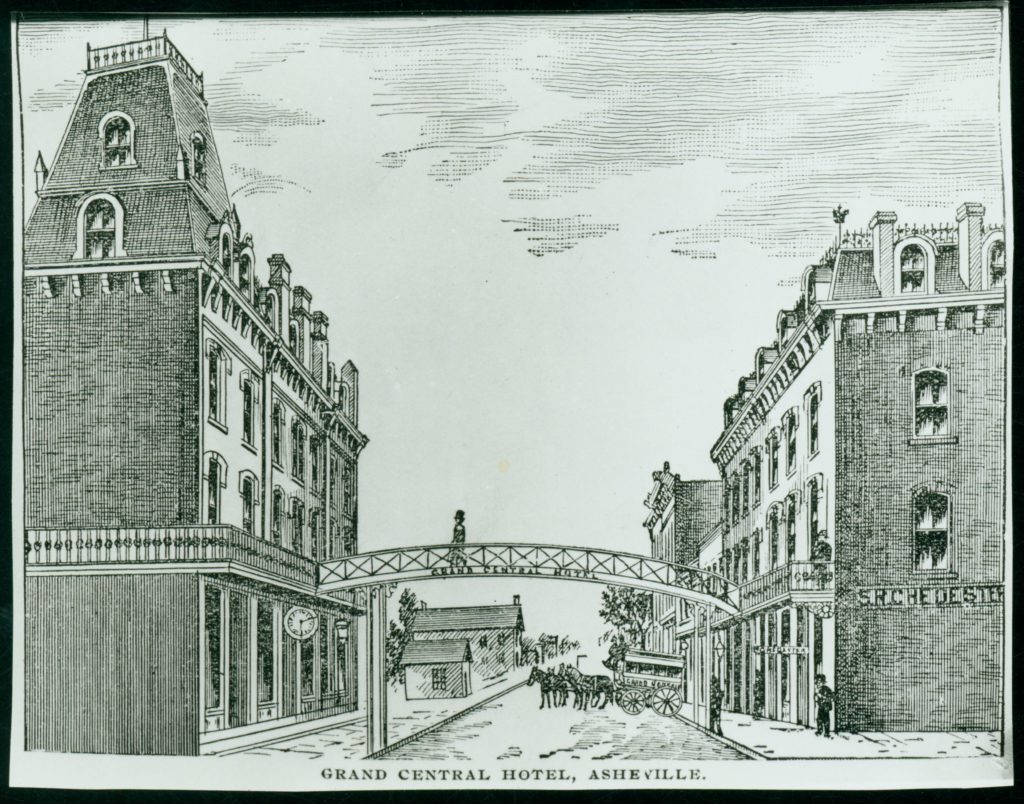

Simultaneous with the design and construction of the Asheville Female College, in 1887, Melton was also working on a large five-story commercial building for S. R. Chedester. The building was to be an annex to Chedester’s Grand Central Hotel, which sat at the corner of what is now Lexington and Patton Avenue (now the site of the Kress Building). The new Melton-designed building was constructed on the southside of Patton Avenue directly across from the Grand Central Hotel and was connected to the hotel with a second story iron-bridge over Patton. The new building had four retail stores on the first floor, with the upper floors being made up of en-suite hotel rooms. This building sat at 22 Patton Avenue, and lasted until the 1970’s, at which time it was demolished, to make way for a parking lot. By the 1970’s, the upper tower and tops of the chimneys had been torn down.

Although A. L. Melton advertised himself as an architect, with “Superintending the construction a specialty”, I suspect that on many of his projects he functioned as a “Design/Build” firm, providing both architectural and contracting services. It was reported on both the Female College and the Chedester Annex that Melton had prepared the drawings and was supervising the construction.

It’s difficult to determine all the specific projects that Melton had between 1887 and 1890 as few were reported in the media (aka newspapers), and the few that were reported were non-specific, such as the report in April of 1890 that reported that Melton had the “contract for eleven houses” with “twenty-one under consideration”,[9] and later in May it was reported that he “will build eight houses”.[10] However, it does bring up the point that Melton had both residential and commercial/institutional commissions. In fact, I’ve found far more reports of residential commissions during his career than of non-residential. The only specific residential project reported in 1888, was a house for Benjamin E. Atkins. B. E. Atkins, a professor of Mathematics at the Asheville Female College, commissioned a house-to be built on the corner of Woodfin & Locust Streets, adjacent to the college. The Atkins house sat on what is now the site of the old Nurses Home on the southside of Woodfin Place across from the former Mission Hospital.

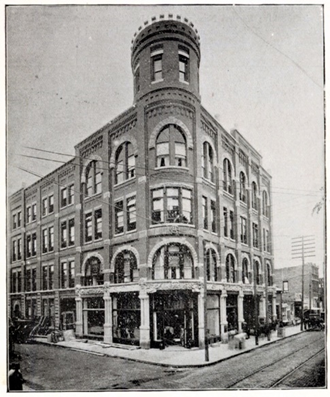

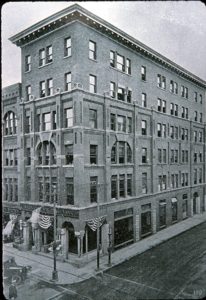

Beginning in 1891, we begin to hear, through the newspaper’s reports, more of Melton’s specific projects. The first reported project in 1891 was for a four-story brick and stone building on the southeast corner of Patton Avenue and Church Street, just down the street from the Chedester Annex. The building was commissioned by lawyer/historian Foster A. Sondley. Soon after its completion, A. L. Melton moved his practice into one of the upper floors. Most of the available photos of the building shows it as a six-story structure, as two additional floors, designed by architect R. S. Smith, were added in the early 1900s.

During 1891, over a dozen residences were reported to have been designed by A. L. Melton. However, I have only been able to locate the sites of handful of them. One that is very identifiable and recognizable is the beautiful and picturesque Queen-Anne style home that Melton designed for Theodore F. Davidson on Liberty Street. Named “Beaufort Lodge” by Davidson, the home is now operated as the Beaufort House Inn. Queen Anne was the preferred style used by A. L. Melton for his residences. Later in his career he also used the Shingle-Style and occasionally the Colonial-Revival, but he seemed to have never ventured into designing in the Craftsman Style, which flourished late in his career.

Another residence designed by Melton in 1891 was a two-story house for W. H. Penland on Haywood Street. The home which was built on the east side of Haywood on the site where the Vanderbilt Apartments (just north of Pack Library) now sits. Before it’s demolition around 1925 to make way for the new George Vanderbilt Hotel, the home was the residence and office of Dr. H. H. Briggs at 73 Haywood Street. The house is shown in a 1914 panoramic photo taken by noted photographer Herbert Pelton. We have the drawings for this house[11], but not Melton’s originals, but a later set of floor plans and elevations and details, drawn by R. S. Smith for an addition/renovation in 1904. At that time, the plan was reconfigured to function both as Dr. Briggs’ office and family residence. The Smith drawings show the Melton-designed projecting tower and wrap-around veranda with turned posts and balusters. The photos show that the Melton-designed posts and balusters on the verandah had been replaced with R. S. Smith-styled posts, railings and balusters.

In 1894, Melton designed. perhaps his most identifiable building, the “Drhumor Building”, which still stands on the southwest corner of Patton Avenue and Church Street. The building was commissioned by William Johnston Cocke, and built on the site of his grandfather, William Johnston’s former 1840 brick residence. Named for the Johnston family’s ancestral home in Ireland, the Drhumor building not only complemented the Sondley Building on the adjacent corner, but both buildings were four-stories in height and built of brick with stone base floors with stone accents and trim. The first-floor stone friezes were carved by Fred Miles, a talented stone carver who had come to Asheville to work on the Biltmore House. Initial and contemporary reports noted Miles’ work on the building, proving his notoriety at the time. The building originally had a tower atop the corner bay. That feature was removed in the 20th century, and the entrance was shifted to Patton Avenue and given a large arched frame. The building remains a one of the few surviving examples of Asheville’s late 19th century commercial structures.

Today we have more surviving examples of Melton’s residential commissions than his commercial/institutional work. A number of these are in Montford, whose development coincided with Melton’s career. But before we look at the surviving examples, I’d like to touch on two substantial houses which Melton designed in Montford, which at the time were notable, yet they have not survived. Late in 1898, Tench Charles Coxe, son of Col. Frank Coxe, creator of Battery Park Hotel, commissioned architect Melton to design a 20-room stone and wood shingle mansion for he and his new bride. Although described by a contemporary reporter in 1899 as “Italian Gothic”[12], Coxe’s home, christened “Klondike”, was designed in the “Shingle-style”, then popular for country estates of wealthy Victorians. The stylish residence sat at 475 Montford Avenue, until its demolition in 1970.

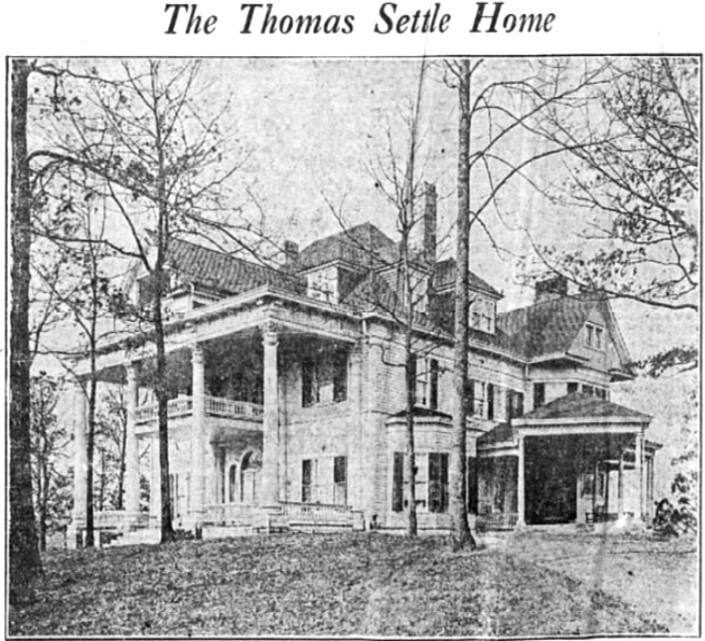

Another notable, but now little-known Melton-designed residence built in Montford, was the Colonial-Revival frame residence for Congressman Thomas Settle. Settle, who was married to the sister of Tench Coxe (of Klondike), shortly after the Coxes completed Klondike, purchased a nine-acre site from and adjacent to the Coxe property. Melton chose the Colonial-Revival, as the Settles had asked that the house pay homage to Orton Plantation, the Cape Fear home of Mrs. Settle’s Great Uncle Fred Hill.[13] The home certainly presented a stately-plantation presence with its front two-story portico with colossal white columns and second-story balcony. The Settles appropriately named their home “Orton”. The magnificent home sat on the north end of Pearson Drive (the present-day site of 435 Pearson Drive) on a nine-acre prominence which overlooked the French Broad River. At the time Orton was built, Pearson Drive circled the house on the south and west and descended to intersect with Riverside Drive. I believe the house remained until the 1950’s-the site is now divided into numerous small lots.

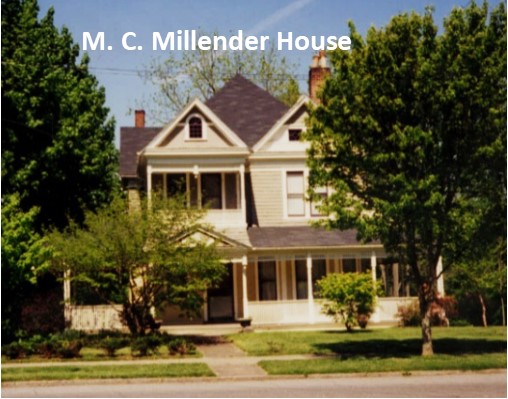

Now for a few Melton-designed homes that are still existing as part of Montford’s historic neighborhood. In 1896, Melton designed a 10-room house, “of the most modern plan”[14], for Dr. Marion C. Millender, on lot #10, on the east side of Montford Avenue adjacent to the Montford Park. This Queen Anne-style house still stands at 333 Montford Avenue and has been lovingly restored and occupied by Vic & Sharon Fahrer. Also in 1896, Melton designed a simple house for Mr. A. Cowley and is wife at the corner of Cumberland and Magnolia Avenues. The house, now addressed as 153 Cumberland Avenue, was designed with a mix of Queen-Anne and Shingle-style motifs.

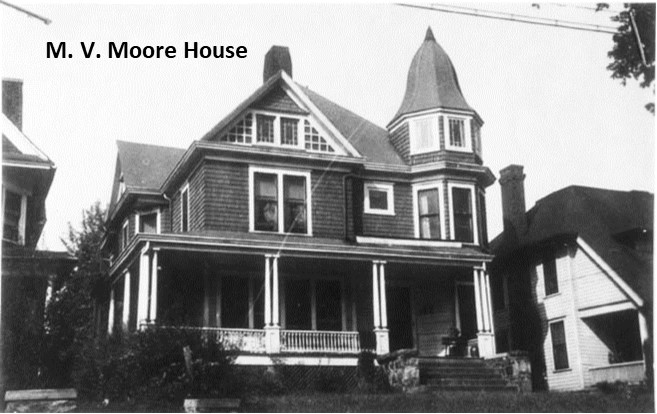

In 1898, Melton designed a Queen-Anne style house for undertaker James Vann Brown, at 167 Pearson Drive. This house featured two of Melton’s signature motifs, a projecting tower and wrap-around verandah. The house is lovingly maintained by its current owners, Ben & Wyo Porter. Also, in 1898, Melton designed a Queen-Anne styled house for Mr. & Mrs. Matthew Van Moore at 110 Cumberland Avenue. Like the J. V. Brown House, the Moore house was not only designed in the same Queen-Anne style, but it too had Melton’s signature motifs- a projecting tower and wrap-around verandah. A vintage photo shows “stickwork” panels in the front gable and decidedly Victorian turned porch posts and balusters on the verandah. This house, though it has survived, had suffered much damage over the years, including the complete removal of its verandah, prior to his purchase by the current owner, John Morris, who is now tenderly restoring the home to its former elegance.

Melton’s output was so prolific that I have decided to divide this study into two parts. Later, in Part 2 we will look at more projects and even delve a bit into the personal life of “A. L. Melton, Architect”.

Photo Credits:

- Judge Avery’s House– By Warren LeMay from Cullowhee, NC, United States – Alphonse Calhoun Avery House, Morganton, NC, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=83671183

- Haywood County Courthouse– North Carolina Postcards, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. https://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000221

- Asheville Female College-Image B242-8, North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

- Grand Central Hotel and Annex image and photo- North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

- Sondley Building– photo- North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

- Beaufort Lodge– photo by Mary Jo Brezny- North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

- H. Penland/Briggs House– photo by Herbert Pelton, North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

- Drhumor Building– North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

- Klondike- North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

- Thomas Settle House– -from Asheville Citizen Times, August 1, 1920, page 8.-newspapers.com

- C. Millender House (333 Montford Avenue)- North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

- Cowley House (153 Cumberland Avenue)- North Carolina Collection, Pack Memorial Library, Asheville, NC.

- V. Brown House (167 Pearson Drive)- realtor.com

[1]1880 United States Federal Census, Morganton, Burke County, North Carolina- ancestry.com

[2] “Town Improvements”, The Blue Ridge Blade, Morganton, NC- April 17, 1880, page 3. From newspapers.com

[3] Ibid.

[4] https://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000221

[5] Ibid.

[6] “They Say”, Asheville Advance, September 14, 1886, page 1.

[7] “The Asheville Female College-The New Building”, Asheville Citizen-Times, May 1, 1887, page 1.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Asheville Citizen-Times, April 1, 1890.

[10] Asheville Citizen-Times, May 20, 1890, page 1.

[11] See -North Carolina Collection, RS0375.1 -7, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

[12] Asheville Daily Gazette, August 6, 1899, page 6.

[13] Asheville Citizen-Times, January 21, 1919, page 3.

[14] Asheville Citizen-Times, December 31, 1896, page 1.