by Dale Wayne Slusser

February is the month for Lovers! Here in Asheville we think of it as the month for lovers of bungalows, and of all things Arts & Crafts, Mission-Style, and Craftsman, as hundreds of bungalow lovers descend upon Asheville to attend the National Arts and Crafts Conference and Shows at the Grove Park Inn. While researching to write the “house histories” for this year’s Preservation Society-sponsored Tour of Homes (part of the Conference) I was reminded that the Arts & Crafts Movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had a quick, yet enduring influence on residential housing across the United States. It’s influence in Asheville was proliferated throughout Asheville’s historic housing stock and continues to influence residential development even today.

One “architectural tidbit” we often overlook (and often fear to admit) is the fact that a huge percentage of our historic housing stock was not specifically designed by an architect, but built by builders from published plans. The rise of the Arts & Crafts Movement coincided with the rise of the prefabricated homes sold by large retail chains such as Sears, Roebuck & Co. and Montgomery Wards and specialty retailers such as Gordon Van-Tine, Bennetts, and Radford Homes. In my research, I’ve found that very often builders simply copied their plans from the catalogs published by these companies, and even more often they simply adapted their plans from published plans. I present two recent examples that I have come across from the Norwood Park neighborhood.

Like many houses built in Asheville during the ‘Roaring 20’s real estate boom, the houses at 108 and 110 Norwood Avenue were built by builders from plans, or at least influenced by, plans from published house plan books of the 1920’s. Real estate mogul, John Acee, in April of 1919, purchased four lots from Bledsoe & Co.-lots 99, 100, 101, and 102 on the eastside of Virginia Avenue (now called Norwood Avenue). Bledsoe & Company, although they were a real estate firm, operated more like builders and developers. On November 17, 1919, an article in the Asheville Citizen-Times reported that two residences have “just been completed” in Norwood Park and two additional residences “are being erected, at an average cost of $7,000”. It was further reported that also being constructed in Norwood Park was a “residence for John Acee to cost about $7,500” (which I believe to be the house at 108 Norwood). Bledsoe and Robinson built the house for John Acee, even providing financing from N. T. Robinson (of Bledsoe & Co.).

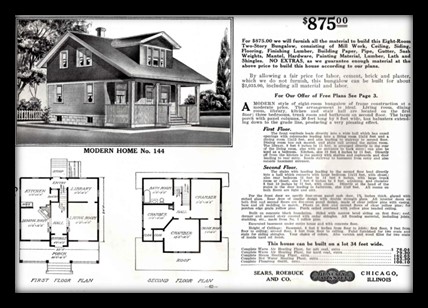

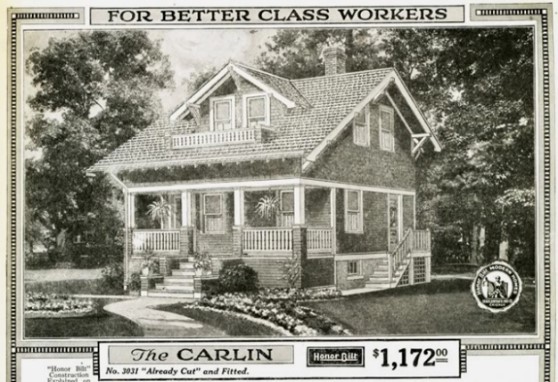

Bledsoe & Co. being builders, generally used published house plans, or derivatives of such plans. Although the floor plan of the house at 108 Norwood does not match a published plan, its style is certainly based on a popular published “Modern Home” plan from Sears, Roebuck & Co. In their 1912 catalog, Sears first labeled the plan as “Modern Home No. 144”, but in future catalogs, it was called “The Westly”. Similar derivative plans included “The Carlin”, “The Windsor”, and “The Sunbeam” (which has the front dormer as a sleeping porch). This became a very popular plan/style and was often copied by other plan books and builders. The design includes a reverse salt-box roof with the front of the roof beginning just a few feet above the front porch, and then sweeping up to the top of the second-floor wall at the rear of the house. A large front gabled dormer is an essential feature in this design, and in the case of 108 Norwood Avenue, the dormer was originally designed as a “sleeping porch” with its front wall of windows. One difference of 108 Norwood compared to the published plans is that its roof extends higher to encompass a third-floor attic.

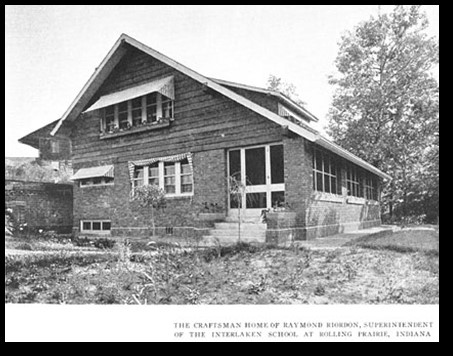

This house embodies all the elements of an Arts & Crafts Bungalow, with its all its interior space under one roof. Also, its large roof overhangs with timber roof brackets, are hallmarks of the Arts & Crafts style. The general antecedents for this style can be seen Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1905 design for the E. A. Davenport house. And an even closer, although more scholarly, antecedent is Raymond Riordan’s bungalow in Rolling Prairie, Indiana. Riordan was an educator and founder of the Interlaken School, and was connected with Gustave Stickley’s work at Craftsman farms. Stickley featured Riordan’s house in a 1913 issue of The Craftsman.

John Acee sold the house at 108, in January of 1920, to Harry & Edith Parker. Acee also sold Lot 99 and a portion of Lot 101 to the Parkers. In 1922, the Parkers sold off the vacant to Emma D. Folsom. After a short succession of owners, the still vacant lot was sold to Irene D. Lyda in 1927. Lyda decided to have a small house built on the narrow lot.

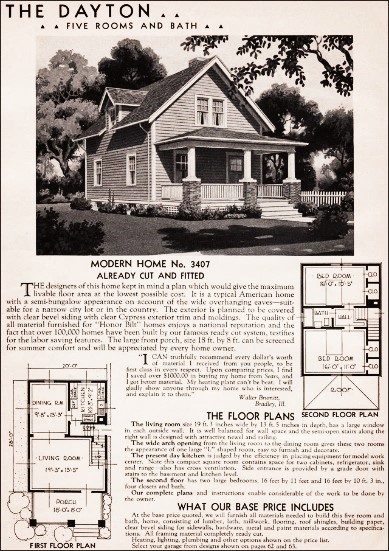

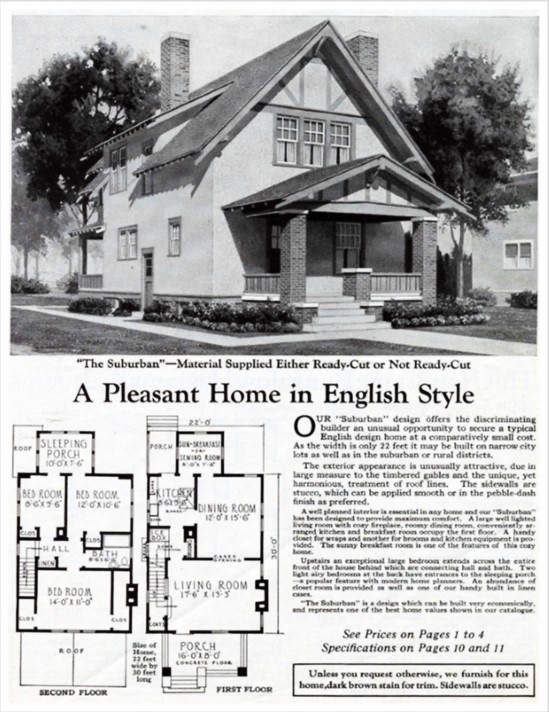

I can’t find who the contactor was for the Lyda house (which would become 110 Norwood Avenue), but I strongly suspect its design came from, or at least was adapted from, one of the popular “plan books” of house plans which proliferated during the 1920’s. The one-and-a-half story house with a steep front-facing gable with side dormers and simple front porch had numerous variants in the plan books. Even as late as the 1930’s this type of house was being offered by Sears, Roebuck and Co. In their 1937 catalog, they published “The Dayton”, which was as simplified as the house at 110 Norwood. Sears advertised this design as “a typical American home with a semibungalow appearance”.[1]

The closest published plan that I have found to house at 110 Norwood was called “The Suburban” from a 1925 catalog of Wardway Homes, a division of the Montgomery-Wards retail chain. The very same plan, with even the same rendering of the house, was published and marketed in a 1923 catalog of the Gordon-Van Tine Company, another purveyor of prefabricated “kit” houses. In the Gordon-Van Tine catalog, the plan was called “The Dayton”. The house that Irene Lyda built at 110 Norwood closely matches these plans, though the “style” instead of stuccoed-Tudor as shown in the published homes, was changed to simple Craftsman-style with wood siding. The 22-foot-wide by 30 feet deep dimensions of the Lyda house even match the published plans. This was a perfect choice for the narrow “suburban” lot.

The use of published plans became so popular by the first quarter of the twentieth century, that professional architects decided “get into the game” and join together to provide their own published plans. A group of Minnesota architects created the “The Architects’ Small House Service Bureau” in 1914 to provide a solution for the shortage of middle-class housing in the U.S. By 1919, the bureau had offices throughout the U.S. and received the endorsement of both the American Institute of Architects and the Department of Commerce. During this time, the members of the Bureau produced hundreds of plans sets and monthly bulletins to assist homeowners with their housing choices. The monthly magazine, in conjunction with the published plan books–Your Future Home and How to Plan, Finance, and Build Your Home–dispensed valuable information to potential homebuyers across the nation.[2]

Perhaps the best summation of the enduring appeal of the Arts & Crafts-style for homes, comes from a 1929 publication by The Architects’ Small House Service Bureau, titled, Small Homes of Architectural Distinction. One of their published plans for a stuccoed bungalow, is titled “Bungalows Go On Forever[3]”. “Styles in houses come and go,” exclaims the editor, “but bungalows go on forever”!

Image credits:

- Streetscape Photo: Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County

- House photos: Carolina MLS

- All published plans from: https://www.antiquehomestyle.com

- Riordon House from: “The evolution of a hillside home: Raymond Riordon’s Indiana bungalow”, The Craftsman, Vol. XXV, Number 1 (Eastwood, N.Y.: United Crafts), October 1913, page 49. http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/DLDecArts/DLDecArts-idx?type=turn&entity=DLDecArts.hdv25n01.p0051&id=DLDecArts.hdv25n01&isize=M

[1] The Dayton, from Houses by Mail, by Katherine Cole Stevenson & H. Ward Jandl Washington DC: National Trust for Historic Preservation Press, 1986) page 82.

[2] “The Architects’ Small House Service Bureau and the American Institute of Architects” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277582964_The_Architects’_Small_House_Service_Bureau_and_the_American_Institute_of_Architects

[3] “Bungalows Go On Forever”, from Authentic Small Houses of the Twenties, (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1987), page 94.