by Dale Wayne Slusser

When I’m asked to research the history of a house, the foremost question I’m asked is: “Who built my house?” Of course, implicit in that question are really three questions, “Who commissioned my house to be built?”, “Who designed my house?”, and “Who was the builder?”. The first question is usually easy to determine after preparing a chain of title and searching newspaper announcements. The second and third questions are often more difficult to determine and require additional digging. First, I must determine if the builder and designer/architect were one in the same, or separate, as was more often the case after 1865. I usually just assume that the builder and architect were local, but recently while researching the history of a historic house in Montford, I was reminded that beginning in the mid-Victorian era, many homes were not just influenced by published house plans, but that they were often built directly from “mail-order plans”.

A year ago, Dr. Eric Halvorson and his wife Rebecca, inquired of the Preservation Society, if the society had any information about their recently purchased historic house at 179 Montford Avenue. Their inquiry was referred to me. After researching the history of their home, I was unable to determine neither the builder nor the architect. However, I suggested that Dr. Halvorson should look through the W. H. Westall ledgers[1] at the North Carolina Room at Pack Library for possible clues.

Several months later, Dr. Halvorson re-contacted me to inform me that he had found from the ledgers that Milton Harding was probably the builder of their house. Being somewhat acquainted with Milton Harding’s work, I told Dr. Halvorson that although Harding advertised himself as an architect and builder, that Harding was mostly likely the builder but probably not the architect of the house. To me, the sophistication of the design and its style resembled the shingle styled houses being built at the time on the northeast coasts of Massachusetts and Maine. And since we knew that the house was commissioned to be built in December of 1891 by retired USA Naval Commander George Thomas Davis of Greenfield, Massachusetts, I entertained the possibility that the house was designed by a northeast architect, but alas, I could find no connections. The answer came a few months later from an unexpected source and in a very fortuitous manner.

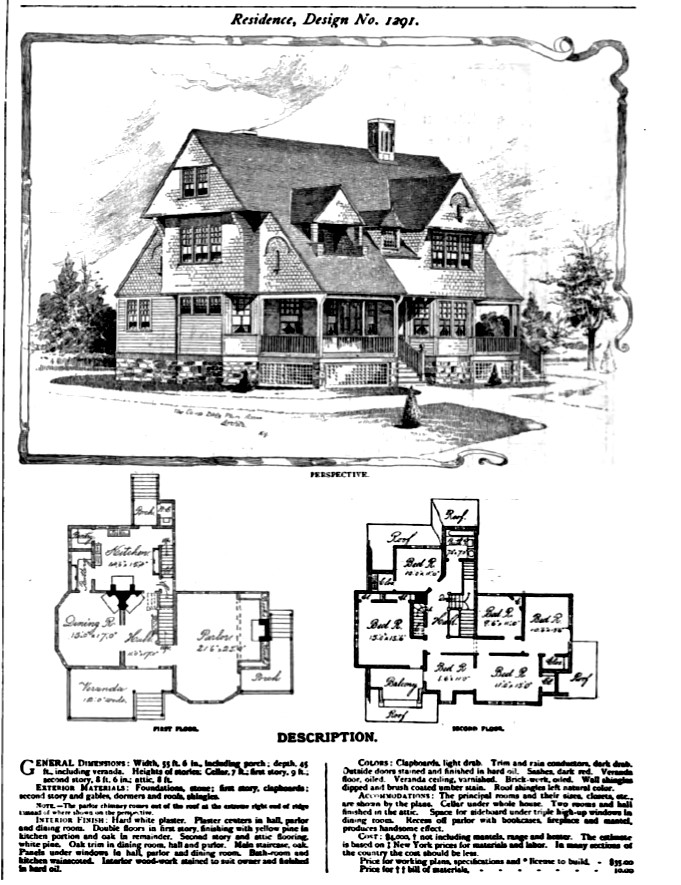

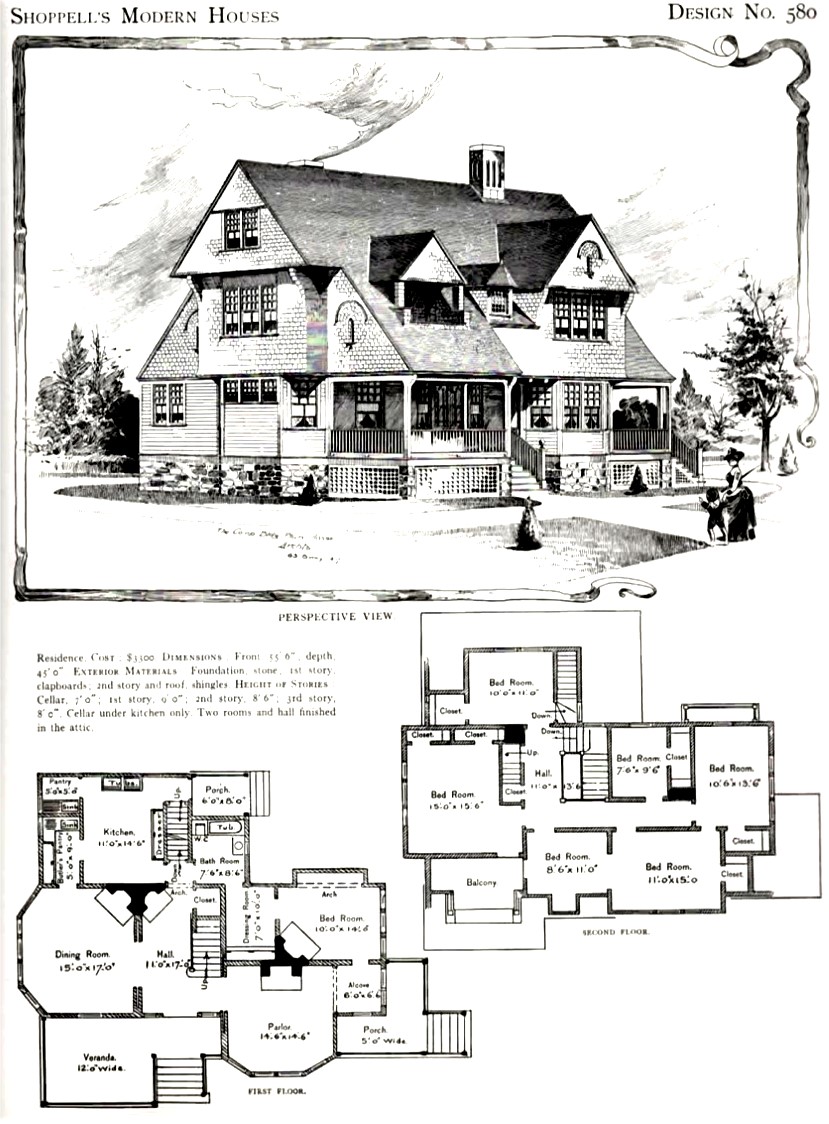

Last week, while researching another project on newspapers.com, I pulled up the front page of an 1890 issue of The North Carolinian from Elizabeth City[2] when I spied a “house plan” complete with floor plans and “Perspective View”. Those published plans have always caught my eye, so I decided to scan over to it and have a look. Instantly I recognized its resemblance to the house built at 179 Montford Avenue. The advertisement was signed by “R. W. Shoppell, Architect”. Admittedly, I had not heard of Shoppell, nor had I even considered the possibility that the house may have been built from mail-order plans!

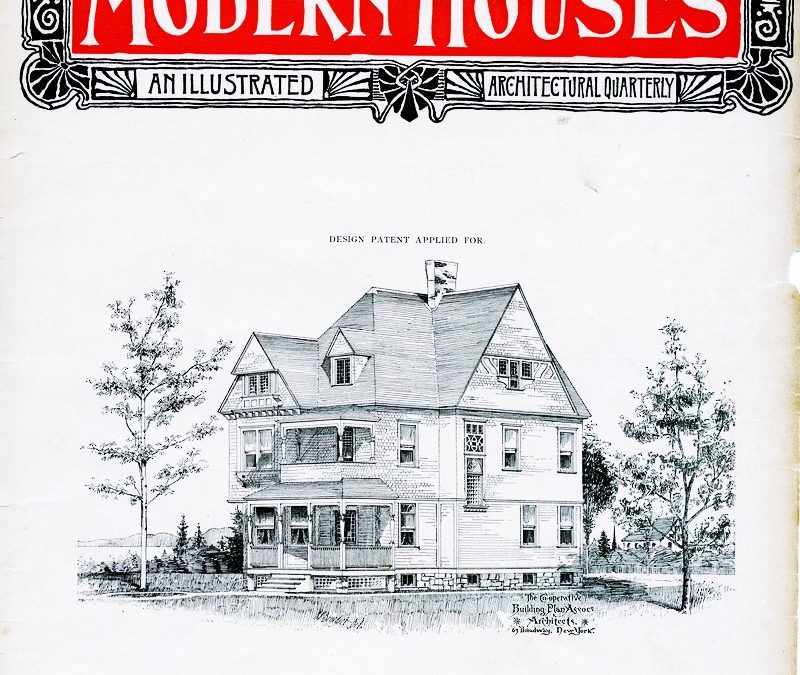

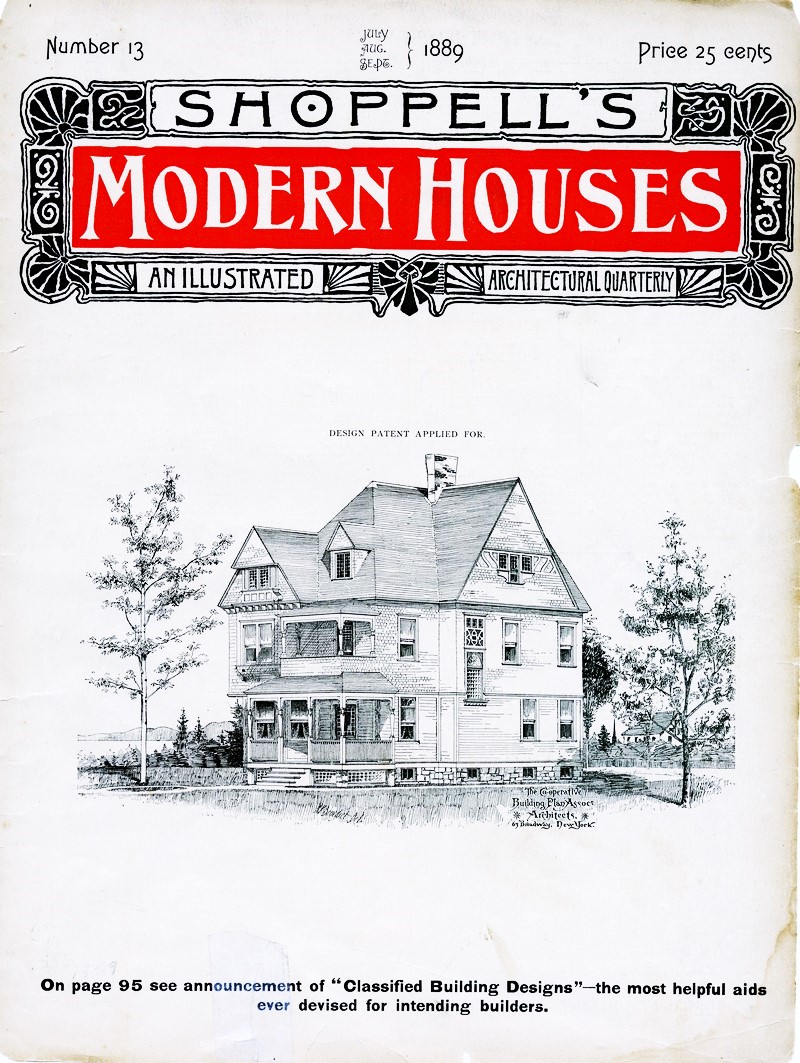

New York architect, Robert W. Shoppell, founder of the “Co-Operative Building Plan Association”, beginning in 1881, with the publication of Artistic Modern Homes of Low Cost, “issued low-cost catalogs of a wide range of house designs from which one could order drawings and specifications at reasonable rates.”[3] “From the beginning, the catalogs depicted a perspective illustration, plans, a description, and a cost estimate.”[4] From this the prospective homeowner or builder could order the working drawings complete with plans, elevations, detail sheets and specifications. Additionally, the builder could purchase an accompanying “bill of quantities”, a “color sheet”, and appropriate building contract forms. Shoppell formed the Co-Operative Building Plan Association, a firm made up of architects united together to provide “full architectural services for any of the designs or modifications of the same at a low price (a much lower price than they were actually worth), believing that the duplication of the services (which he called Co-operative for want of a better term), would bring him a proper remuneration”.[5]

After the publication of two additional books, How to Build, Furnish, and Decorate (1883) and Building Plans for Low Cost Houses (1884), in 1886, Shoppell began a quarterly publication titled, Shoppell’s Modern Houses. The quarterly, which greatly increased the distribution of his plans, ran for twenty-two years.[6]

Shoppell’s prolific output of house designs, produced by his office with its staff of “fifty architects and draftsman”[7], made ordering plans from Shoppell more affordable for homeowners than hiring their own architect. This often put him at odds with local professional architects. However, as author Daniel Reiff points out, “[…] for the legion of prospective builders of small homes, who would probably not hire an architect anyway, they [Shoppell] did provide professionally designed dwellings in enormous variety for clients to choose from”.[8] In fact, Shoppell claimed that very reason for establishing his “plan service”. In 1886, Shoppell claimed that before he established his business (five years previous) “that it was difficult, if not impossible to get full architectural services for a price that the public considered low and reasonable.”[9] Shoppell did not blame the architects, and acknowledged that it was often cost prohibitive for an architect to take on the commission for small individual houses, and even when they did take on such commissions, their fees, “though not undeserved by the architect for his work”, were still unaffordable for the average homeowner. The result of this disparity according to Shoppell, “was that most of the houses of moderate cost were built from inferior designs, and lacked the beauty and unity, convenience and economy of arrangements that results from the employment of architects”.[10]

Upon further research through available online Shoppell catalogs, I found that the plan from the North Carolinian was known as “Design 1291”. Consulting with Dr. Halvorson, we decided that this must have been the plan used to build his house, but that builder Harding most likely made some onsite changes to the plan, accounting for the discrepancies in the Halvorson’s floor plan. However, a few days later, while paging through a printed reprint copy of Shoppell’s catalogs (which I had earlier excitedly ordered from Amazon), I found that the house at 179 Montford was built from an earlier “Design 580”, and that “Design 1291” was a later variant plan. The floor plan of the earlier Design 580 almost exactly matched the floor plan of the Halvorson home.

Shoppell labeled his plans by numbers, i.e.: “Design 580”, seemingly to avoid stereotyping each house as a certain house type. But contrary to this premise, in the 1890 advertisement in The North Carolinian, that I stumbled upon, Shoppell gave no number for the design, instead he titled it as “A Country House”. Now to put this into context- to the Victorians, a “Country House” did not mean a farm dwelling or cabin in the woods (those were called “Farmhouse” or “Cottage”). Instead, “a country house” denoted a summer or vacation home for those of means, where they could enjoy elegant leisure, “far from the madding crowd” and free from society and work pressures. Clearly this house (Design 1291 and 580) was intended to be built as a leisure home on a large lot, probably on a promontory, bluff or cliff overlooking the sea (or lake), where it could take the most advantage of the cool breezes and scenic views.

Commander Davis and builder Harding successfully adapted the “country home” to its urban setting and narrow lot by turning the house ninety-degrees, putting its intended “front” to the side yard. They also compensated for turning the front entrance door to the side, by bringing a circular drive up from the street directly to the side of the front porch. A short walk from the drive delivered one quickly and easily to the front entrance. Another adaptation was to enlarge the parlor by incorporating the “Alcove” and portion of the adjacent porch. The exterior door from the parlor was then turned to face the rear and open on to what became a rear porch.

Another adaptation which didn’t involve a change in the plan, but made the house work in its urban setting, was to face the dining room bay windows to the street side. From its vantage point, visitors invited to evening dinners and soirees could easily see where the “party” was being held! Also, by setting the house back from the street, raised above the sidewalk gave the house a sense of prominence it seemed to deserve.

The front with it’s overhanging shingled components displayed the best of the Shingle-Style, where sculptural elegance is achieved through massing and artful installation of its wooden shingles. Even decoration and ornament are achieved using shingles, especially displayed on the front façade with its shingled brackets, flanking slit windows with shingled round arched lintels, and the row of saw-tooth edged shingles at the bottom of the third-floor gable.

Shoppell’s working drawings also included detailed drawings of all interior trim, mantels and stairways, doors and windows, however since we do not have the original working drawings for Design 580, we cannot evaluate how closely the builder kept to the drawings. But Shoppell did often publish sketches of “good examples of tasteful styles” to which we can compare. The stair railing with its turned-spool shaped balusters closely matches one of Shoppell’s examples. The fireplace mantles with their simple brackets supporting a simple mantle shelf also resemble Shoppell’s examples. I suspect, though, that W. H. Westall, which produced the millwork, doors and windows sashes for the house at 179 Montford, also had some influence over the design of those components as well, although the result is very much in keeping with Shoppell’s designs and sketches of interiors.

Since much of Asheville’s historic housing stock dates from the late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century, the period when Shoppell’s designs were being produced and widely distributed, I suspect that we may find other homes, besides the elegant house at 179 Montford Avenue, that were built from Shoppell’s tasteful and affordable plans– Be on the lookout!

Photo credit:

Newspaper article from newspapers.com.

Illustrations from Shoppell’s catalogs.

House photos taken by Dr. Eric Halvorson.

[1] MS206.001A W H WESTALL CO. LEDGER-1890 TO 1892 & MS206.00 1B-W.H.WESTALL CO. LEDGER — CASH ACCOUNTS — 1890 TO 1900. Ledgers for the W.H. Westall Co., dealers in sash, doors and blinds. The lists contain debtor’s name, items purchased, and costs. Some listings include a building name specific to a project. North Carolina Collection, Pack Library, Asheville, NC.

[2] The North Carolinian, Elizabeth City, NC- April 16, 1890, page 1.

[3] Daniel D. Reiff, Houses from Books: The Influence of Treatises, Pattern Books, and Catalogs in American Architecture, 1738-1950. (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000), page 110.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid, page 111.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Shoppell’s Modern Homes: An Illustrated Quarterly, Vol. 1 No. 3, edited by Robert W. Shoppell and Stanly S. Covert. (New York, NY: The Co-Operative Building Plan Association, Architect, July 1886), page 145.

[10] Ibid.